Abstract

Purpose

Lung cancer and its treatment impose many demands on family caregivers, which may increase their risk for distress. However, little research has documented aspects of the caregiving experience that are especially challenging for distressed caregivers of lung cancer patients. This study aimed to explore caregivers' key challenges in coping with their family member's lung cancer.

Methods

Single, semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with 21 distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients.

Results

Caregivers described three key challenges in coping with their family member's lung cancer. The most common challenge, identified by 38 % of caregivers, was a profound sense of uncertainty regarding the future as they attempted to understand the patient's prognosis and potential for functional decline. Another key challenge, identified by 33 % of caregivers, involved time-consuming efforts to manage the patient's emotional reactions to the illness. Other caregivers (14 %) characterized practical tasks, such as coordinating the patient's medical care, as their greatest challenge.

Conclusions

Results suggest that clinical efforts are needed to assist distressed caregivers in providing practical and emotional support to the patient and attending to their own emotional needs.

Keywords: Family caregiver, Lung cancer, Psychological distress, Health, Quality of life

Introduction

Family caregivers of cancer patients have increasingly assumed responsibility for patient care due to the decline in health care resources, shorter hospital stays, and the associated expansion of outpatient care [1, 2]. Family caregivers have been defined as those who assist ill relatives or friends with self-care and medical tasks as well as those who provide informational, financial, and emotional support [3, 4]. Many family caregivers of cancer patients face a range of stressors, including disrupted household and work routines, family role changes, financial strain, and personal health conditions [5, 6]. Together, these stressors help explain the clinically elevated distress reported by up to 50 % of cancer patients' family caregivers [7–11].

Lung cancer may be particularly distressing for family caregivers because of its high physical symptom burden [12], poor prognosis [13], and stigma or attributions of blame, particularly when the patient persists in tobacco use [14]. To date, studies have used standardized questionnaires to document decrements in mental health, social functioning, and quality of life among family caregivers of lung cancer patients [10, 11, 15, 16]. About one third of spousal caregivers of lung cancer patients have shown clinically significant distress [10, 11]. In one qualitative analysis of the effect of lung cancer on the spousal relationship, couples reported difficulty discussing the patient's prognosis, physical symptoms, and continued tobacco use as well as the caregiver's emotional reactions [17].

Limited qualitative research has been conducted with family caregivers of lung cancer patients [18–21], and this research has primarily focused on describing caregivers' social, emotional, and existential distress [18–20] and their interactions with the health care system [21]. To date, caregivers have not identified the most challenging aspects of their caregiving experience, and an established distress criterion has not been used for study entry. It is important to understand the aspects of the cancer caregiving experience that are especially challenging for distressed caregivers so as to develop interventions to mitigate caregiver distress. Therefore, the goal of this qualitative study was to identify distressed caregivers' key challenges in coping with their family member's lung cancer. Our analysis could further our understanding of factors that potentially contribute to caregivers' distress.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Family caregivers of lung cancer patients were recruited from a comprehensive cancer center in New York City. All study procedures were approved by the cancer center's institutional review board. Eligible lung cancer patients were English speakers who were within 12 weeks of a new visit to the thoracic oncology clinic. Patients with lung cancer recurrence were ineligible for this study. Patients' eligibility status was determined via medical record review and consultations with oncologists. A research assistant consecutively approached eligible patients during clinic visits to describe the study. Lung cancer patients identified and provided permission to contact their primary family caregiver and collect cancer-related information from their medical record. A research assistant screened caregivers for eligibility and completed the informed consent process in the clinic or via telephone. Participating caregivers were English speakers who were at least 18 years of age and showing significant anxiety or depressive symptoms as indicated by self-reported scores meeting the clinical cutoff (≥8) on the anxiety or depression subscales of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [22, 23] at the time of recruitment. Meeting this clinical cutoff suggests that the person may have a diagnosable anxiety disorder or depression. All caregivers who completed the HADS received a brochure outlining various support services (e.g., psychological, psychiatric, and social work services) available at the cancer center.

Caregivers completed standardized telephone assessments of their health and well-being at baseline and 3 months later. Caregivers who did not receive mental health services (i.e., individual or group psychotherapy or psychiatric medication) during the 3-month study period were invited to participate in an in-depth, semi-structured telephone interview within 1 to 3 weeks of the follow-up assessment. Excluding caregivers who had recently received mental health services allowed us to focus on the specific challenges and barriers to help-seeking faced by distressed caregivers who did not yet have the benefit of professional psychosocial care.

Interviews were performed by a master's level qualitative methodologist with extensive experience interviewing medical patients and their family members. The interview included questions about caregivers' greatest challenges in caring for the patient, their barriers to using mental health services, and their service preferences. Interviews ranged from 35 to 50 min and were digitally recorded. The present analysis focused on caregiver's responses to the following question: “What has been the most challenging aspect of dealing with your [e.g., husband's/wife's, father's/mother's] illness?” Caregivers were then asked to “describe the challenge and the steps that you took to deal with the challenge.” The interviewer asked follow-up questions to obtain a detailed narrative of their challenges. Caregivers' responses to interview questions on barriers to using mental health services and service preferences will be published in a separate report. Caregivers received compensation for study participation.

Caregivers reported their sociodemographic information at baseline. Information regarding the patient's lung cancer and its treatment were collected from medical records. Caregivers also reported whether the patient had received chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery at baseline and follow-up.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into Atlas.ti software for thematic analysis [24]. Thematic analysis is a method of qualitative analysis that involves identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns or themes across a data set. We chose an inductive or data-driven approach to thematic analysis rather than a theoretical approach due to the descriptive and exploratory nature of this study [24]. The first two authors generated initial codes after reading all transcripts. Using Atlas.ti, the authors then independently coded the essays and met at regular intervals to review the codes and reconcile differences until complete agreement was reached. The authors then sorted the codes into broader themes and checked to ensure that data within themes were consistent and that the themes were distinct from one another.

Results

Sample characteristics

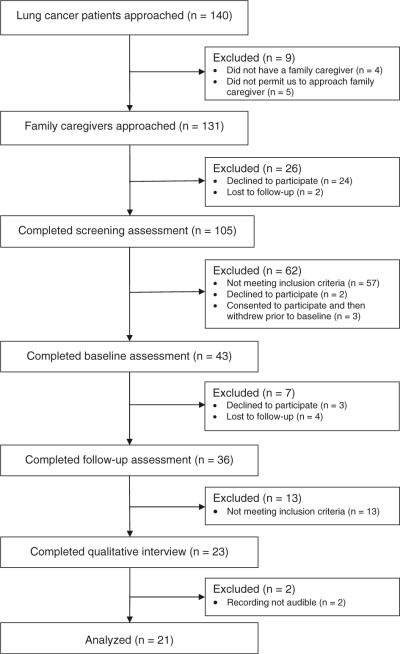

Of the 140 lung cancer patients who were approached regarding this study, 97 % (n=136) identified a family caregiver (see Fig. 1). Most patients (96 %, n=131) allowed the research assistant to contact their caregiver. The majority of caregivers (80 %) agreed to complete the HADS to determine their eligibility status, 18 % declined to participate, and 2 % were unable to be reached via phone. Primary reasons for study refusal were time constraints, personal stress, and a desire to focus on the patient's needs. Almost half of caregivers (46 %, n=48 of 105) met the clinical cutoff (score≥8) for significant anxiety or depressive symptoms on the HADS. Most eligible caregivers (96 %, n=46) consented to participate in this study.

Fig. 1.

Study schema

Forty-three caregivers (93 %) completed the baseline phone assessment, and 36 caregivers completed the follow-up phone assessment (78 % retention). Reasons for withdrawal included time constraints, personal illness, bereavement, and inability to reach the caregiver via phone. Eligible caregivers who completed follow-up were consecutively invited to complete the qualitative interview. All of the caregivers (n=23) agreed to participate in the interview, but data from two caregivers could not be analyzed because the digital recordings were not audible. With 21 participants, the authors jointly determined that thematic saturation had been reached. Saturation is the point at which no new narrative content codes are apparent in the data analysis, and additional interviews are not expected to significantly change the content codes.

Demographic and medical characteristics of the sample are found in Table 1. Participants were, on average, 53 years old, married, female, Caucasian, and well-educated (mean=15 years of education). Most caregivers reported an annual household income of more than $100,000. Caregivers were spouses/partners (67 %) or adult children (33 %) of the patient. All of the patients had non-small cell lung cancer, and the majority (67 %) were newly diagnosed with stage III or IV disease. Patients were, on average, 6 weeks from the lung cancer diagnosis at baseline. None of the caregivers were bereaved at the time of the qualitative interview.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N=21)

| Variable | n (%) | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver sex—female | 16 (76) | ||

| Type of relationship | |||

| Spouse/partner | 14 (67) | ||

| Adult child | 7 (33) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 15 (71) | ||

| African American/Black | 4 (19) | ||

| Other | 2 (10) | ||

| Caregiver age (years) | 53 (12) | 30–71 | |

| Caregiver marital status | |||

| Married or marriage equivalent | 20 (95) | ||

| Divorced | 1 (5) | ||

| Caregiver annual household income (median) | >$100,000 | ||

| Caregiver education (years) | 15 (2) | 11–19 | |

| Caregiver employment status | |||

| Working full or part time | 14 (67) | ||

| Retired | 5 (24) | ||

| Homemaker or unemployed | 2 (10) | ||

| Weeks since patient's diagnosis at baseline | 6 (5) | .14–15 | |

| Lung cancer stage | |||

| Early stage (I or II) | 6 (29) | ||

| Late stage (III or IV) | 14 (67) | ||

| Missing | 1 (5) | ||

| Type of treatment | |||

| Surgery | 10 (48) | ||

| Chemotherapy | 15 (71) | ||

| Radiation | 7 (33) |

Qualitative findings

Thematic analysis [24] of caregivers' responses to interview questions identified three key challenges in dealing with the patient's illness: facing an uncertain future, managing the patient's emotions, and managing day-to-day tasks. Each of these challenges is described below.

Facing an uncertain future

Eight caregivers (38 %) described a profound sense of uncertainty regarding the future as their greatest challenge. This uncertainty centered on the patient's potential functional decline and prognosis, as illustrated by the following comment from the wife of an early-stage patient: “Before he had cancer… I felt that both of us would grow old together. Now all of a sudden that concept was gone. We didn't know how long he was going to live. We didn't know what the end would look like. Will he be totally incapacitated?” The caregiver then noted her family's efforts to cope with this uncertainty by taking one day at a time and accepting and processing information during each medical appointment. The husband of a late-stage patient expressed a similar perspective: “You think… you're going to retire and you're going to go live somewhere nice until you're 90 years old, right, as a couple… and then all of a sudden, the thought that that might not be the outcome is a challenge.” He then stated that he had reached a state of “acceptance” regarding his wife's illness.

In an effort to manage their uncertainty regarding the future, three caregivers of late-stage patients focused on medical treatment decision-making. One of the caregivers said that gathering extensive cancer-related information from doctors, friends, and the Internet had only intensified his fear that his wife was not receiving a potentially curative treatment. He said: “We always face this dilemma about which [doctor] to choose… this battle is with her life… it's so painful. We ended up going to so many doctors…. You always think, `What if someone has something that could work wonders, magic on her'.” Another caregiver made numerous phone calls in an effort to find the appropriate hospital and physician for his wife. A third caregiver, the health care proxy for her mother, compiled considerable information regarding her mother's treatment preferences in preparation for changes in her functional status. Taken together, findings suggest that caregivers often had worries about the future and dealt with these worries by accepting the reality of the illness and attempting to direct aspects of the patient's medical care.

Managing the patient's emotions

Managing the patient's emotions was the second most common challenge, reported by 33 % (n=7) of family caregivers. Efforts to improve the patient's mood most often involved distracting the patient with routine activities. One wife of a late-stage patient described this approach: “I'm trying to occupy him so he doesn't think… I make him go shopping with me, or I tell him, `let's go for a ride. I don't want to stay in the house.' Or we'll go in the backyard and sit under a tree and just talk.”

Caregivers of early-stage patients were more likely than those of late-stage patients to try to improve the patient's mood by noting the positive aspects of their circumstances. One wife of a patient with multiple early stage cancers provided the following examples of her positive statements: “This could always be worse. You've been lucky. It's a primary site. It's very early. They've caught it right away.” Conversely, one caregiver thought that encouraging words would not help her husband adjust to his early stage diagnosis.

Some caregivers devoted much of their time to managing the patient's emotions. One husband of a woman with late-stage cancer said that he needed to be “by her side all the time” due to her severe anxiety. He described maintaining a physical presence at her bedside that involved holding her hand and speaking words of encouragement. Similarly, one daughter of a late-stage patient with anxiety and depression said: “I'm always the one that has to be with her physically… I'm the one who has to sit with her and try to pull her out of it.” The caregiver then expressed frustration regarding her mother's initial resistance to seeking mental health services and subsequent emergency room visits for psychiatric care.

Caregivers who did not live with the patient also described time-consuming efforts to provide emotional support to the patient and other family members. Several of these caregivers called their family members multiple times a day to monitor their emotions and frequently visited the patient's home. This provision of emotional support often interrupted other activities, as illustrated by one daughter's comment: “I try to go [to my parents' home] almost every day… some of my things at my home have been left behind… I don't do my cleaning as often as I used to and I have to plan out my life a little bit more in advance… so I can incorporate more time to go see both my parents [and] make sure they're okay.”

Findings suggest that emotional support provision often involved ensuring that the patient did not feel isolated and abandoned. Maintaining a positive attitude and a sense of normalcy were other emotional aspects of caregiving. Our interview data showed that caregivers often placed the needs and interests of the patient above their own. Their attempts to reduce the patient's distress simultaneously served as a means of managing their own emotional reactions to the illness.

Managing day-to-day tasks

Managing practical tasks was the third most common challenge, reported by three adult daughter caregivers (14 %). One caregiver described her challenge as “trying to coordinate everything” for her father and listed her responsibilities: “getting him to the medical appointments, getting him his medication, and then also dealing with the financial aspects of it. Making sure that all his disability forms are filled in so he can get his check on time.” Another caregiver said that convincing her parents to seek cancer care at a different hospital and changing their health insurance to ensure maximal coverage of expenses were especially difficult tasks. A third caregiver said that arranging and providing long-distance transportation to medical appointments for her mother was the most challenging task, as she had other commitments and limited family support. The caregivers indicated that these practical responsibilities contributed to feelings of anxiety and frustration when they experienced unanticipated problems, such as delays in processing insurance claims and cancelled transportation to the patient's medical appointments.

Discussion

This study provides an initial examination of caregiving challenges faced by distressed family caregivers of lung cancer patients. Many caregivers described emotional aspects of caregiving as the greatest challenge. These aspects included time-consuming coping efforts to manage the patient's emotions, including maintenance of “normal” routines and a positive attitude. Attending to the patient's emotions and medical care helped caregivers to manage their own uncertainty regarding the future. Results parallel previous theory and research that has conceptualized “emotion work” as a central aspect of family caregiving [25, 26]. In this study, emotion work involved interconnected efforts to improve the patient's mood and their own feeling states.

Caregivers in our study described their reality as a “dayto-day existence” in which they focused on the patient's immediate physical and psychological needs. For some caregivers, meeting these needs involved extensive efforts to coordinate the patient's medical care and finances. These logistical matters were significant challenges for several caregivers. In the context of lung cancer, a disease with an uncertain or poor prognosis, practical challenges were less salient for caregivers than emotional aspects of caregiving. In addition, most of the caregivers in our study had economic and educational resources to assist them in coping with practical concerns.

Limitations of this study should be noted. First, the majority of our participants were women, and many had moderate to high income and more than a high school education. Thus, the extent to which the findings generalize to men and people of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds warrants examination. However, this sample was relatively diverse in terms of age and medical variables (e.g., disease stage, treatments received), and 29 % were members of ethnic minority groups. Second, only distressed caregivers who had not recently received mental health services were eligible for participation. Further research is needed to determine whether caregivers' challenges vary as a function of level of distress and use of mental health services. Finally, this paper was intended as an overview of caregivers' key challenges. Emotional and practical aspects of caregiving identified in this analysis should be explored in greater detail by both qualitative and quantitative research with larger sample sizes. Conducting multiple interviews over time would allow us to gain a better understanding of caregiving challenges at different phases of the illness trajectory.

The present findings reveal aspects of the caregiving experience that may contribute to decrements in caregivers' quality of life [10, 11, 15, 16] and underscore the need to assist distressed family caregivers with practical and emotional aspects of caregiving. Clinically elevated distress appears to be common among lung cancer patients' caregivers, as suggested by the current research and prior studies with this population [10, 11, 27]. Although a range of services, including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, practical support, and educational interventions, is available to patients' family members at many comprehensive cancer centers [28], these services are typically underused [29]. Given that caregivers often prioritize the patient's needs, their receptivity to support services may increase if they feel that these services do not divert resources and attention away from the patient. Research is needed to develop, evaluate, and disseminate caregiver-focused interventions that are tailored to their needs and preferences [30] and build upon their problem-focused coping efforts (e.g., coordination of patients' medical care) and emotion-focused coping (e.g., acceptance of current circumstances). Such interventions would enhance the quality of life of both patients and care-givers. In addition, research, clinical, and policy efforts are needed to address the limited access to mental health care among individuals of lower socioeconomic status, ethnic minorities, and those with low health literacy [28].

The results also carry implications for clinical practice. First, clinicians may prepare patients' family members for the emotional aspects of caregiving by providing informational and practical resources. This preparation also may involve referring caregivers to resources to enhance their own stress management and maintenance of physical and mental health. A checklist of potential psychosocial and practical concerns may assist with the referral process [31]. These clinical recommendations are supported by the results of a recent meta-analysis suggesting that psychoeducation, skills training, and counseling may reduce distress and enhance aspects of quality of life among cancer patients' caregivers [32]. Finally, acknowledging and validating caregivers' emotions, including their fears of the future, may help caregivers to emotionally process their experience and seek additional support if necessary.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant no. R03CA139862 from the National Cancer Institute. CM was supported by F32CA130600 from the National Cancer Institute and KL2 RR025760 (A. Shekhar, PI) from the National Center for Research Resources. The authors would like to thank the study participants, the thoracic oncology team at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Elyse Shuk and Scarlett Ho for their assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:213–231. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailes JS. Health care economics of cancer in the elderly. Cancer. 1997;80:1348–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nijboer C, Tempelaar R, Sanderman R, Triemstra M, Spruijt RJ, van den Bos GA. Cancer and caregiving: the impact on the caregiver's health. Psychooncology. 1998;7:3–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199801/02)7:1<3::AID-PON320>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stajduhar K, Funk L, Toye C, Grande G, Aoun S, Todd C. Part 1: home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998–2008) Palliat Med. 2010;24:573–593. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaugler JE, Hanna N, Linder J, Given CW, Tolbert V, Kataria R, Regine WF. Cancer caregiving and subjective stress: a multi-site, multi-dimensional analysis. Psychooncology. 2005;14:771–785. doi: 10.1002/pon.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, van Houtven C, Griffin JM, Martin M, Atienza AA, Phelan S, Finstad D, Rowland J. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;20:44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel K, Karus DG, Raveis VH, Christ GH, Mesagno FP. Depressive distress among the spouses of terminally ill cancer patients. Cancer Pract. 1996;4:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun M, Mikulincer M, Rydall A, Walsh A, Rodin G. Hidden morbidity in cancer: spouse caregivers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4829–4834. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grunfeld E, Coyle D, Whelan T, Clinch J, Reyno L, Earle CC, Willan A, Viola R, Coristine M, Janz T, Glossop R. Family caregiver burden: results of a longitudinal study of breast cancer patients and their principal caregivers. Can Med Assoc J. 2004;170:1795–1801. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmack Taylor CL, Badr H, Lee JH, Fossella F, Pisters K, Gritz ER, Schover L. Lung cancer patients and their spouses: psychological and relationship functioning within 1 month of treatment initiation. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:129–140. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, Duberstein PR, Sörensen S, Larson MR. Levels of depressive symptoms in spouses of people with lung cancer: effects of personality, social support, and caregiving burden. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:123–130. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiro SG, Douse J, Read C, Janes S. Complications of lung cancer treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:302–317. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Cancer Society . Cancer facts and figures—2012. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lobchuk MM, Murdoch T, McClement SE, McPherson C. A dyadic affair: who is to blame for causing and controlling the patient's lung cancer? Cancer Nurs. 2008;31:435–443. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000339253.68324.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Persson C, Östlund U, Wennman-Larsen A, Wengström Y, Gustavsson P. Health-related quality of life in significant others of patients dying from lung cancer. Palliat Med. 2008;22:239–247. doi: 10.1177/0269216307085339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badr H, Carmack Taylor CL. Effects of relationship maintenance on psychological distress and dyadic adjustment among couples coping with lung cancer. Health Psychol. 2008;27:616–627. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badr H, Carmack Taylor CL. Social constraints and spousal communication in lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:673–683. doi: 10.1002/pon.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Grant L, Highet G, Sheikh A. Archetypal trajectories of social, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing and distress in family care givers of patients with lung cancer: secondary analysis of serial qualitative interviews. BMJ. 2010;340:c2581. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, Benton TF. Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med. 2004;18:39–45. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm837oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindau ST, Surawska H, Paice J, Baron SR. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. Psychooncology. 2011;20:179–185. doi: 10.1002/pon.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishnasamy M, Wells M, Wilkie E. Patients and carer experiences of care provision after a diagnosis of lung cancer in Scotland. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:327–332. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas C, Morris SM, Harman JC. Companions through cancer: the care given by informal carers in cancer contexts. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:529–544. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00048-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erickson RJ. Why emotion work matters: sex, gender, and the division of household labor. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67:337–351. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Östlund U, Wennman-Larsen A, Persson C, Gustavsson P, Wengström Y. Mental health in significant others of patients dying from lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:29–37. doi: 10.1002/pon.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute of Medicine, editor. Cancer care for the whole patient: meeting psychosocial health needs. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanderwerker LC, Laff RE, Kadan-Lottick NS, McColl S, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use among caregivers of advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6899–6907. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim Y, Given BA. Quality of life of family caregivers of cancer survivors: across the trajectory of the illness. Cancer. 2008;112:2556–2568. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wen K-Y, Gustafson D. Needs assessment for cancer patients and their families. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Song L, Zhang L, Mood DW. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:317–339. doi: 10.3322/caac.20081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]