Abstract

Background/Aims

Weekly granulocyte/monocyte adsorption (GMA) to deplete elevated and activated leucocytes should serve as a non-pharmacological intervention to induce remission in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC). This trial assessed the efficacy of monthly GMA as a maintenance therapy to suppress UC relapse.

Methods

Thirty-three corticosteroid refractory patients with active UC received 10 weekly GMA sessions as a remission induction therapy. They were then randomized to receive one GMA session every 4 weeks (True, n=11), extracorporeal circulation without the GMA column every 4 weeks (Sham, n=11), or no additional intervention (Control, n=11). The primary endpoint was the rate of avoiding relapse (AR) over 48 weeks.

Results

At week 48, the AR rates in the True, Sham, and Control groups were 40.0%, 9.1%, and 18.2%, respectively. All patients were steroid-free, but no statistically significant difference was seen among the three arms. However, in patients who could taper their prednisolone dose to <20 mg/day during the remission induction therapy, the AR in the True group was better than in the Sham (p<0.03) or Control (p<0.05) groups.

Conclusions

Monthly GMA may potentially prevent UC relapse in patients who have achieved remission through weekly GMA, especially in patients on <20 mg/day PSL at the start of the maintenance therapy.

Keywords: Granulocyte monocyte apheresis, Inflammatory bowel diseases, Maintenance treatment, Randomized controlled trial, Ulcerative colitis

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) together with Crohn's disease (CD) are the major phenotypes of the idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which afflicts millions of individuals throughout the world with symptoms that impair quality of life and ability to function.1 Currently, the etiology of UC is not well understood, but mucosal tissue edema, increased gut epithelial cell permeability, and extensive infiltration of the colonic mucosa by leucocytes of the myeloid lineage are major pathologic features of this immune disorder. Accordingly, selective depletion of peripheral granulocyte and monocyte/macrophage by extracorporeal adsorption (granulocyte/monocyte adsorption [GMA]) with an Adacolumn has been applied as a nonpharmacologic treatment strategy to alleviate the inflammatory response in patients with active IBD.2 The primary target of GMA is to deplete elevated/activated circulating myeloid leucocytes, which infiltrate the colonic mucosa in vast numbers during active IBD.2,3 Further, weekly GMA has been accepted as a non-pharmacologic treatment option for IBD patients with an active flare while on conventional medications including high dose corticosteroid. Shimoyama et al.4 were the first to carryout a multicenter trial, and show that steroid refractory UC patients with a severe acute flare could achieve remission and reduce their steroid dosage by combining five GMA sessions over a 5-week period. They also reported significantly less side effects for GMA versus prednisolone (PSL). The outcomes of this multicenter controlled trial in 2000 convinced the Japan Ministry of Health to approve GMA therapy for funding in the national health insurance scheme to treat steroid refractory UC patients with an acute flare. Since then, this treatment option has shown an excellent safety profile together with steroid sparing effect.

In clinical setting, there is a need to establish an effective therapeutic strategy for long-term maintenance of remission without compromising safety.5 Further, it might be reasonable to expect a strategy that is effective as remission induction therapy to work as maintenance therapy as well. An extracorporeal leucocytapheresis system like GMA is expected to have the potential to achieve this intention. There is evidence to support the clinical efficacy for monthly leucocytapheresis as an adjunct maintenance therapy in UC patients with steroid refractory background.6 With this background in mind, in the present study, our objective was to design the first prospective, single center, randomized, sham controlled, double blind trial with three arms to see if monthly GMA can suppress UC relapse in a population of patients who had achieved remission with a series of weekly GMA sessions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. General information

This prospective, single center, randomized, sham controlled, double blind trial with three arms was conducted at the division of Lower Gastrointestinal Disease & IBD Center, Hyogo College of Medicine, Japan between April 2004 and December 2009. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on April 1, 2004, and all patients provided both oral and written informed consent. The study was registered with www.UMIN.ac.jp (number: UMIN000004242).

2. Patients

Eligible patients were men and women aged 12 to 75 years and body-weight ≥39 kg with UC following remission induction intervention involving 10 weekly GMA sessions within 4 weeks prior to the start of this maintenance study. Remission induction therapy with weekly GMA was decided for moderate-to-severe UC in spite of receiving conventional medication. Active disease was defined as clinical activity index (CAI) ≥5, according to Lichtiger et al.,7 and CAI ≤4 was considered clinical remission. Concomitant azathioprine (AZA) and PSL were allowed if had been started before the randomization at a stable dose, but were to be tapered during the trial.

Exclusion criteria included treatment with cyclosporine A, or tacrolimus ≤4 weeks prior to the start of this study, infliximab ≤8 weeks prior to the start of this study. Also, patients with granulocytopenia (neutrophil count, <2,000/µL), serious heart, kidney or liver disorders, coagulation abnormalities, history of hypersensitivity to heparin such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, hypotension (<90/65 mm Hg) or uncontrolled hypertension (>180/120 mm Hg, despite medical therapy); anemia, hemoglobin ≤9.0 g/dL, and women being or wishing to become pregnant, were excluded.

3. Study protocol

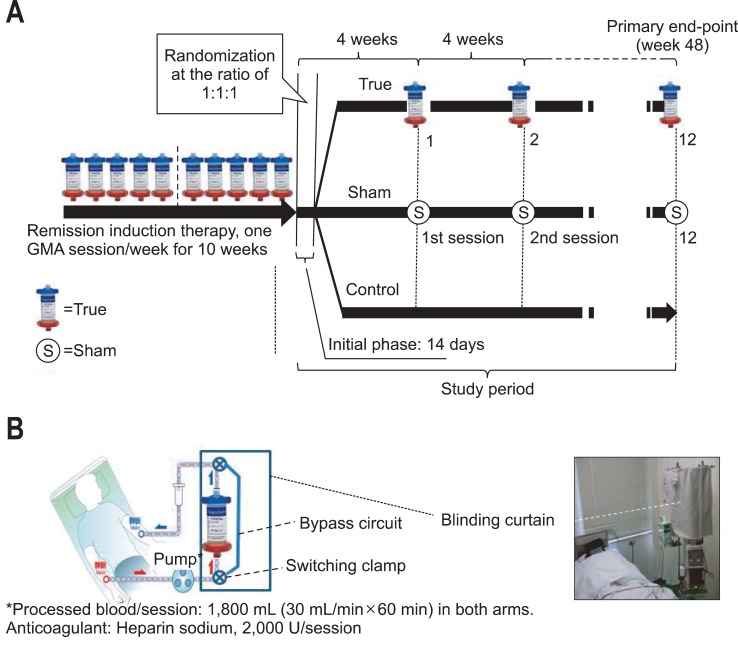

Fig. 1A shows the design of the present trial. Within 14 days following the last weekly GMA session as remission induction therapy, we obtained both oral and written informed consent and then the eligible patients were randomized to one of the three arms (True, Sham, or Control) of the study for maintenance therapy. Patients who were assigned to the True arm received monthly GMA, patients in the Sham arm received monthly 1 hour extracorporeal blood circulation without the GMA column (circuit lines only; Fig. 1B), and patients in the Control arm remained on their ongoing conventional medications. Patients were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio by a statistician at an independent organization. Since this was a pilot trial with small sample sizes, randomization was done blindly according to a computer-generated scheme with blocks of three (each three patients were randomly allocated to True, Sham, or Control). This was to minimize the risk of unbalanced group sizes. This trial was designed as proof-of-concept (of active intervention) as opposed to a definitive evaluation of the monthly GMA therapy. Therefore, the primary goal was to evaluate the likely effective size and appropriate candidate patients for this non-drug intervention as a guide for subsequent evaluation in a large cohort of patients. Based on previous experience,5 we assumed that 60% of patients without receiving GMA or be on placebo would have a clinical relapse within 1 year. Since this was a single institute trial, a power of 75% and a 2-sided type-I error rate of 5% were assumed. The study size was anticipated to be a 1:1:1 randomization of 72 patients (24 in each arm) for detecting a group difference, and a sustained remission of 40% in both the Sham and the Control arms, while in the True (GMA) arm, it was expected to be twice this level.

Fig. 1.

(A) The study design showing the patient treatment with the remission induction therapy course involving 10 weekly granulocyte/monocyte adsorption (GMA) sessions followed by the remission maintenance therapy: 1 GMA session every 4 weeks (True), Sham GMA every 4 weeks (Sham; blood lines without the Adacolumn) or no additional treatment (Control). The patients who completed the series of weekly GMA therapies were randomly assigned to one of the three groups as shown. (B) The blood flow circuit diagrams for both the GMA (True) and Sham GMA are shown. In the Sham GMA, a bypass was added to the standard GMA circuit lines. Patients in the Sham group received the same volume of extracorporeal circulation via the Adacolumn circuit lines, similar to the sham design by Sands et al.9 Both patients and the physician were blinded by a curtain.

4. Treatment

GMA was done with the Adacolumn as previously described.2,4,5 Briefly, the Adacolumn is filled with specially designed cellulose acetate beads, which serve as the column adsorptive leucocytapheresis carriers.2 The carriers selectively adsorb from the blood in the column about 65% of granulocytes, 55% monocytes/macrophages and a significant fraction of platelets, which bear the FcγR and complement receptors; lymphocytes are spared and subsequently increase.2 The patients assigned to the True arm, each received one GMA session every 4 weeks for up to 48 weeks. The duration of one session was 60 minutes, at 30 mL/min (similar to the weekly GMA). An optimum dose of sodium heparin (2,000 units/session) as an anticoagulant was administered during both GMA and the sham procedures. Nafamostat mesilate (a common anticoagulant during leucocytapheresis in Japan) was avoided as this substance is associated with allergic reactions.8 The Sham GMA was based on the design by Sands et al.,9 having the circuit blood lines without the Adacolumn itself. The circulation time for the Sham GMA was 60 minutes, at 30 mL/min (the same as in True). The circuit line was covered securely by a curtain to blind both the physician and the patients on the type of treatment (Fig. 1B).

5. Efficacy assessment

The primary endpoint of the study was a non-relapsing ratio (% avoiding relapse [AR]) over week 48. Relapse was considered if a patient experienced a flare-up severe enough to warrant PSL administration or increase the ongoing PSL dose or give another set of GMA sessions during the follow-up period with CAI ≥5. Further, to evaluate mucosal UC activity prior to the start of the study, we compared colonoscopic findings between pre- and post-remission induction therapy with GMA. Also, patients who achieved sustained remission up to week 48 had colonoscopy at week 48.

6. Ethical considerations

GMA with the Adacolumn is a Japan Ministry of Health approved treatment option for patients with active IBD. Additionally, the investigation was carried out in accordance with the Principle of Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki at all times. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the local Ethics Committee on first March 2004, and all patients provided informed consent. In the case of under age patients, consent from one of the patient's parents was sought.

7. Statistics

Quantitative variables were compared by using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. The measures of long-term outcomes were assessed by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, while categorical data were analyzed by the two-sided Fisher exact test. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Patient characteristics and disposition

Seventy-three corticosteroid refractory patients with active UC, each received up to 10 GMA sessions with the Adacolumn over 10 weeks as remission induction therapy in the initial phase of this study. Then, 33 of these patients who had achieved remission agreed to participate in the present, second phase of the study to receive GMA as maintenance therapy. Of the original 73 patients, 40 could not be included because they did not achieve a CAI score of 4 during the GMA remission induction therapy (n=20), declined to participate (n=15), or could not be followed over the planed 48 weeks (n=5). Demographic characteristics of these 33 patients is presented in Table 1. Among patients in the 3 arms, there was no significant difference in demographic variables prior to beginning of either the remission induction therapy, or GMA maintenance therapy.

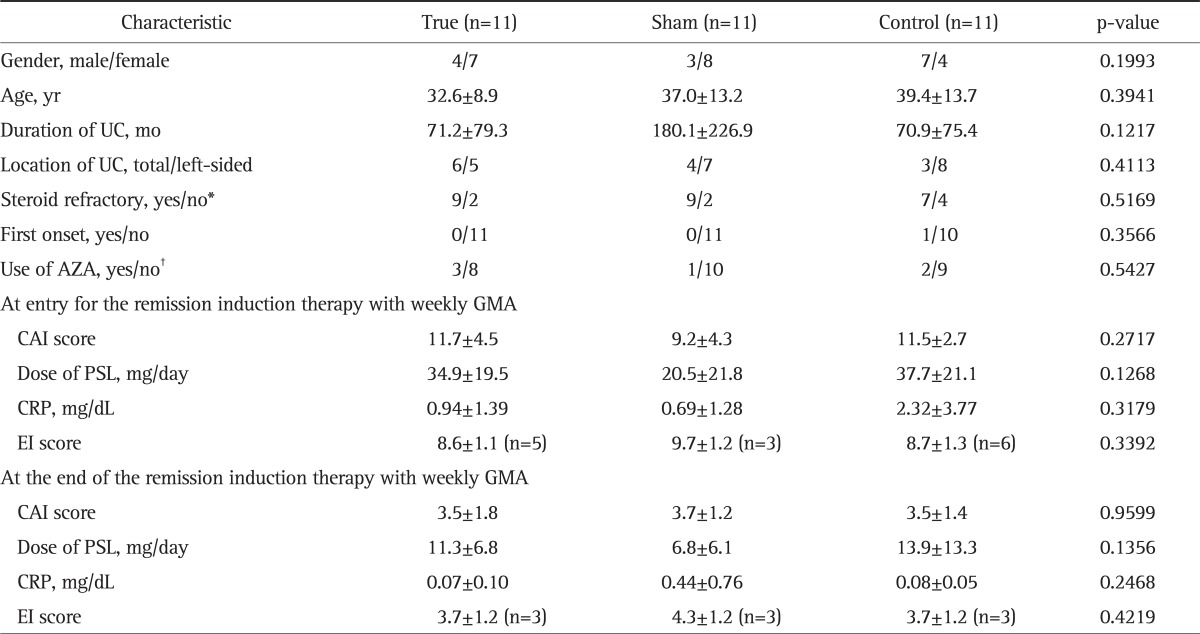

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Enrolled Patients Are Shown (n=33)

Data are presented as mean±SD.

UC, ulcerative colitis; AZA, azathioprine; GMA, granulocyte/monocyte adsorption; CAI, clinical activity index; PSL, prednisolone; CRP, C-reactive protein; EI, endoscopic index.

*Steroid refractory was defined as active disease in spite of an optimum dose of PSL for 14 days; †AZA, 0.5-1.0 mg/day.

2. The overall clinical outcomes

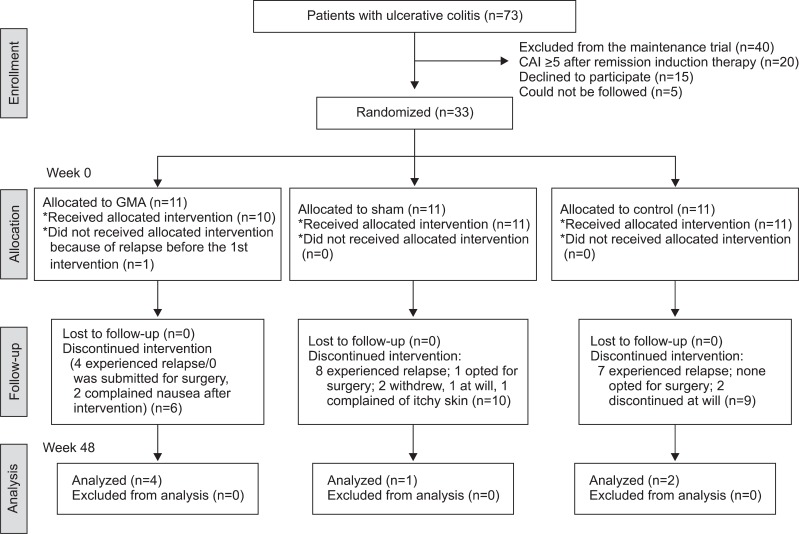

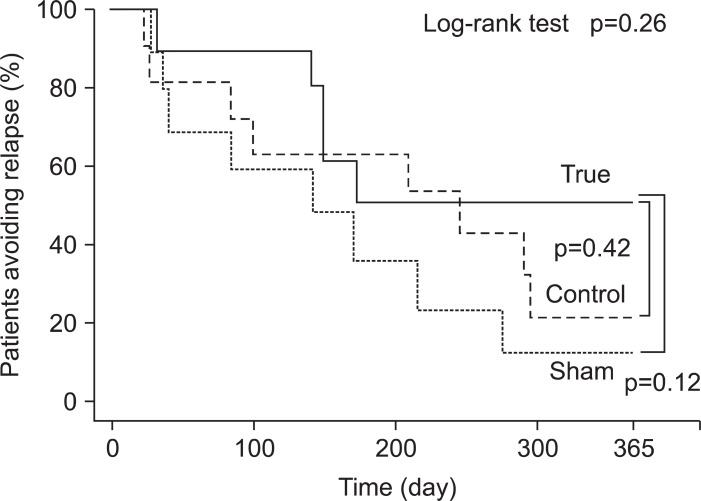

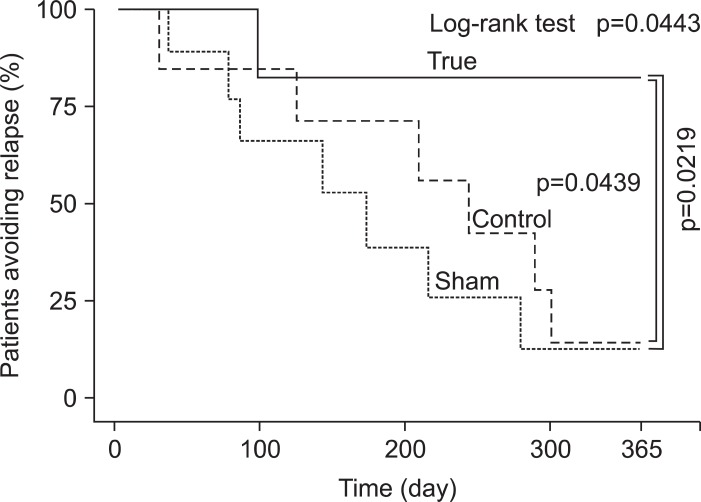

In Fig. 2, the overall clinical outcomes in the 3 arms of the study (True, Sham, and Control) are presented. One patient in the True arm had to be excluded because this patient experienced a clinical relapse before receiving the 1st monthly GMA session. Similarly, one patient in the Sham arm willingly withdrew from the study 10 days after receiving the first monthly Sham GMA session. In the Control arm, one patient was unable to attend, and one decided to sign up for another trial. At week 48, AR rates in True, Sham, and Control were 40.0%, 9.1%, 18.2%, respectively, yet statistically no significant difference was seen between the three arms (Fig. 3). Among our patients, we have decided to evaluate the cases who could reduce their PSL dosage to <20 mg/day during remission induction therapy as "low dose PSL sub-group" in order to impress the efficiency of monthly GMA more clearly. The number of such patients in True, Sham, and Control were 7, 10, and 9, respectively. The low dose PSL sub-group had longer duration of UC (p=0.0451) in addition to the PSL dosage at the end of their remission induction therapy. There was no significant difference between these two sub-groups with respect to other demographic variables. Fig. 4 shows the AR values in the "low dose PSL sub-group." The overall result of the low dose PSL sub-group in a log-rank test at the primary end-point was significantly higher in favor of True versus other two groups (p=0.433). All patients who avoided relapse up to week 48 became PSL free. Accordingly, we believe that the monthly GMA should increase the long-term survival (without relapse) as indicated by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (p=0.0219, vs Sham; p=0.0439, vs Control). To see any contribution from AZA to the clinical efficacy associated with monthly GMA, we compared the results of patients on concomitant AZA with those without AZA in each of the three arms. However, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis did not show significantly better remission maintenance in favor of concomitant AZA (data not presented).

Fig. 2.

Treatment of the patients and summary of the clinical outcomes.

CAI, clinical activity index; GMA, granulocyte/monocyte adsorption.

Fig. 3.

The survival analysis of allocated patient is shown (n=33). The probability of avoiding relapse (AR) (% AR) following a series of 10 weekly granulocyte/monocyte adsorption treatments tended to be higher in the True group at the primary end-point compared with the other two arms. However, a log-rank test did not reveal a statistically significant difference between the True group and the other two groups (p=0.2641). In addition, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis did not indicate a significant difference between the True and Sham groups (p=0.1297) or between the True and Control groups (p=0.4240).

Fig. 4.

The % AR in the low (<20 mg/day) prednisolone subgroup is shown. The % avoiding relapse (AR) following the remission induction with weekly granulocyte/monocyte adsorption was maintained by 57.1% of the patients at the primary end-point. A log-rank test indicated a significantly higher % AR in the True group than in the other two groups (p=0.0443). In addition, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicated a significantly better prognosis for the True group than either the Sham (p=0.0219) or Control (p=0.0439) groups.

There was no serious adverse side effect suspected of 30 mL/min×60 min of extracorporeal circulation procedures in either True or the Sham arm. However, in the True arm, two patients complained of nausea several hours after completing a GMA session (Fig. 2). They decided to withdraw from this study in spite of the fact that their nausea symptom had disappeared without medication. Also, their CAI was maintained within remission level, ≤4 even with their PSL having been discontinued. In the Sham arm, one patient showed mild skin itchiness on both forearms without eruptions, appearing during the second extracorporeal circulation session. Further, in the Sham arm, a 37-year-old patient with left hemi-colitis type of 14 months duration had to opt for surgery 3 months after starting maintenance Sham GMA. This was the only patient of this trial who received surgical treatment.

DISCUSSION

In this investigation, the hypothesis was that monthly GMA is effective as maintenance therapy in patients who had just achieved clinical remission. From the viewpoint of remission maintenance, we believe that it is significant to use a strategy, which is effective in inducing remission of the active disease, and then the same strategy should be used as maintenance therapy. It is also important to state that all patients of this study had a corticosteroid refractory background prior to remission induction therapy with weekly GMA. Furthermore, this was a prospective exploratory study with a total of 33 patients, which limits the statistical significance level. Nonetheless, the clinical outcomes over 48 weeks were encouraging to us.

In this prospective trial, we could not demonstrate a superior efficacy rate for monthly GMA as maintenance therapy in UC patients as compared with either Sham or Control, but the obtained results have inspired us to conduct a future trial with large cohorts of patients because the percentage of patients who could maintain clinical remission up to week 48 in the three arms of this study was in the following order: GMA (40.0%)>Control (18.2%)>Sham (9.1%). Overall, compliance was good, and there was no severe adverse side effect in any arm. Transient flushing and lightheadedness were seen in a small number of patients associated with extracorporeal circulation. These observations are in line with the reports in previous studies with GMA in patients with UC.2,4,10-13 However, the safety profile of the Adacolumn GMA is in sharp contrast to pharmacologics which are often associated with serious adverse side effects that further complicate the ongoing IBD.3,14,15

Further, a significant fraction of patients in each arm were on concomitant PSL or AZA and this enabled us to assess the contribution of these medications (albeit in small sub-groups) to the efficacy of monthly GMA as maintenance therapy. In reference to patients who had their PSL dose tapered to <20 mg/day by the end of the remission induction therapy with weekly GMA, the number of patients with steroid free remission was significantly in favor of GMA at week 48. This is to say that monthly GMA increased the probability of long-term remission in this population as indicated by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. To evaluate the contribution of AZA, we compared the results between patients with and those without concomitant AZA in each of the 3 arms. Unlike the situation with PSL, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis did not show beneficial effect for concomitant AZA. This is not surprising given that only 6 patients were on AZA at the randomization (in Japan, AZA was officially approved for UC patients in June 2006).

Since the publication of the first clinical trial on GMA in patients with UC,4 a large number of papers, mostly from Japan,12,13,16-18 but also from Europe,11,19,20 and the USA9,21,22 have reported varying efficacy outcomes ranging from 85%20 to a statistically insignificant level.9 Except for four studies4,9,20,23 all other studies did not include Control arms. Both Shimoyama et al.4 and Hanai et al.23 used PSL in their Control arms and in all these three studies GMA efficacy was better or equal to PSL. In contrast to these studies, Maiden et al.20 used GMA to suppress clinical relapse in one arm, while the Control arm received no treatment. At the end of a 6-month follow-up, relapse rate was lower and time to clinical relapse longer in the GMA arm. In a randomized, double blind, controlled trial in patients with active UC by Sands et al.,9 patients in the Control arm received the same volume of extracorporeal circulation without the Adacolumn (Sham). In this study, the clinical outcomes between the two arms did not reach statistical significance. Nonetheless, sub-group analysis indicated a significant efficacy for GMA in patients with severe histological evidence of inflammation.9 However, patients with deep colonic lesions and extensive loss of the mucosal tissue are reported to be very poor responders to GMA.17 In spite of unmatched efficacy outcomes in the hitherto studies, currently, the clinical application of GMA with the Adacolumn is expanding in Europe and in Japan. One of the most unrivalled features of GMA with the Adacolumn, which is very much favored by the patients, is its safety profile; severe adverse side effects are very rare. Even in studies with poor efficacy outcome, its safety profile has been acknowledged.9 Therefore, it is our intention to continue using GMA as a safe and effective therapeutic option for achieving sustained steroid free clinical remission.

In conclusion, GMA with the Adacolumn as a non-drug based treatment intervention has an excellent safety profile, it is very much favored by patients and our impression is that the use of therapeutic GMA will expand rather than diminish. The overall outcome of this small, but the first prospective randomized sham-controlled trial could not demonstrate a superior efficacy rate for monthly GMA as maintenance therapy in patients with quiescent UC and a steroid-refractory background. However, monthly GMA appeared to increase the probability of AR in the long term, especially in patients who had reduce their PSL dosage to <20 mg/day at the start of maintenance therapy. Therefore, monthly intervention with GMA potentially should prevent UC relapse without compromising safety. Additional trials in large cohorts of patients should strengthen our findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Professor Yoshikazu Muraoka of the Mathematics Unit, Hyogo College of Medicine for designing a perfect randomization and blinding work. Also, we should like to thank Nobuyuki Hida, MD, Yoshio Ohda, MD, Masaki Iimuro, MD, and Koji Yoshida, MD of the Division of Lower Gastroenterology, Hyogo College of Medicine for supplying patients. No external funding was used in conducting this trial. Similarly, the authors have absolutely no conflict of interest in connection with the publication of this manuscript. Also, this work was supported in part by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for research on intractable diseases from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Isaacs KL, Lewis JD, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Targan SR. State of the art: IBD therapy and clinical trials in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(Suppl 1):S3–S12. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000184852.84558.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saniabadi AR, Hanai H, Fukunaga K, et al. Therapeutic leukocytapheresis for inflammatory bowel disease. Transfus Apher Sci. 2007;37:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison MC, Dhillon AP, Lewis WG. Inflammatory bowel disease. London: Mosby; 1998. pp. 9–95. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimoyama T, Sawada K, Hiwatashi N, et al. Safety and efficacy of granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis in patients with active ulcerative colitis: a multicenter study. J Clin Apher. 2001;16:1–9. doi: 10.1002/jca.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukunaga K, Nagase K, Kusaka T, et al. Cytapheresis in patients with severe ulcerative colitis after failure of intravenous corticosteroid: a long-term retrospective cohort study. Gut Liver. 2009;3:41–47. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2009.3.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawada K, Muto T, Shimoyama T, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled trial for the treatment of ulcerative colitis with a leukocytapheresis column. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:307–321. doi: 10.2174/1381612033391928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagase K, Fukunaga K, Ohnishi K, Kusaka T, Matoba Y, Sawada K. Detection of specific IgE antibodies to nafamostat mesilate as an indication of possible adverse effects of leukocytapheresis using nafamostat mesilate as anticoagulant. Ther Apher Dial. 2004;8:45–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-0968.2004.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Feagan B, et al. A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study of granulocyte/monocyte apheresis for active ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:400–409. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshino T, Nakase H, Matsuura M, et al. Effect and safety of granulocyte-monocyte adsorption apheresis for patients with ulcerative colitis positive for cytomegalovirus in comparison with immunosuppressants. Digestion. 2011;84:3–9. doi: 10.1159/000321911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domènech E, Hinojosa J, Esteve-Comas M, et al. Granulocyteaphaeresis in steroid-dependent inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, open, pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1347–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka T, Okanobu H, Yoshimi S, et al. In patients with ulcerative colitis, adsorptive depletion of granulocytes and monocytes impacts mucosal level of neutrophils and clinically is most effective in steroid naive patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hibi T, Sameshima Y, Sekiguchi Y, et al. Treating ulcerative colitis by Adacolumn therapeutic leucocytapheresis: clinical efficacy and safety based on surveillance of 656 patients in 53 centres in Japan. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Present DH. How to do without steroids in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2000;6:48–57. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SL, Greene MH, Gershon SK, Edwards ET, Braun MM. Tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy and lymphoma development: twenty-six cases reported to the Food and Drug Administration. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3151–3158. doi: 10.1002/art.10679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto T, Saniabadi AR, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Impact of selective leukocytapheresis on mucosal inflammation and ulcerative colitis: cytokine profiles and endoscopic findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:719–726. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki Y, Yoshimura N, Fukuda K, Shirai K, Saito Y, Saniabadi AR. A retrospective search for predictors of clinical response to selective granulocyte and monocyte apheresis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:2031–2038. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakuraba A, Motoya S, Watanabe K, et al. An open-label prospective randomized multicenter study shows very rapid remission of ulcerative colitis by intensive granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis as compared with routine weekly treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2990–2995. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bresci G, Parisi G, Mazzoni A, Scatena F, Capria A. Granulocytapheresis versus methylprednisolone in patients with acute ulcerative colitis: 12-month follow-up. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1678–1682. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiden L, Takeuchi K, Baur R, et al. Selective white cell apheresis reduces relapse rates in patients with IBD at significant risk of clinical relapse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1413–1418. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz D, Ferguson JR. Current pharmacologic treatment paradigms for inflammatory bowel disease and the potential role of granulocyte/monocyte apheresis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2715–2728. doi: 10.1185/030079907x233241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abreu MT, Plevy S, Sands BE, Weinstein R. Selective leukocyte apheresis for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:874–888. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180479435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hanai H, Iida T, Takeuchi K, et al. Intensive granulocyte and monocyte adsorption versus intravenous prednisolone in patients with severe ulcerative colitis: an unblinded randomised multi-centre controlled study. Dig Liver Dis. 2008;40:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]