Abstract

Background/Aims

First-line therapies against Helicobacter pylori, including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) plus two antibiotics, may fail in up to 20% of patients. 'Rescue' therapy is usually needed for patients who failed the first-line treatment. This study evaluated the eradication rate of bismuth-containing quadruple rescue therapy over a 1- or 2-week period.

Methods

We prospectively investigated 169 patients with a persistent H. pylori infection after the first-line triple therapy, which was administered from October 2008 to March 2010. The patients were randomized to receive a 1- or 2-week quadruple rescue therapy (pantoprazole 40 mg b.i.d., tripotassium dicitrate bismuthate 300 mg q.i.d., metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d., and tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d.). After the 'rescue' therapy, the eradication rate, compliance, and adverse events were evaluated.

Results

The 1-week group achieved 83.5% (71/85) and 87.7% (71/81) eradication rates in the intention to treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses, respectively. The 2-week group obtained 87.7% (72/84) and 88.9% (72/81) eradication rate in the ITT and PP analyses, respectively. There was no significant difference in the eradication rate, patient compliance or rate of adverse events between the two groups.

Conclusions

One-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy can be as effective as a 2-week therapy after the failure of the first-line eradication therapy.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Second-line, Eradication, Bismuth tripotassium dicitrate, Rescue

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori infection is recognized as an important factor involved in non-ulcer dyspepsia, peptic ulcer diseases, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma.1,2 Eradication of H. pylori infection prevents ulcer recurrence3,4 and may lead to significant reduction of gastric cancer risk among those without any gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia.5 Several large clinical trials and meta-analyses have shown that the most commonly used first-line therapies, including proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) plus two antibiotics, may fail in up to 20% to 25% of patients.6-9 In the clinical setting, the treatment failure rate might be even higher. The patients who failed H. pylori eradication must be treated by 'rescue' therapy. According to the Maastricht III Consensus Report, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy remains the best second-line treatment option, if available.10 Thus, a second-line, quadruple treatment with PPI, bismuth salts, tetracycline and metronidazole has been generally recommended in patients not cured by first-line treatment.6,10 Although the other regimens combined with newer antibiotics to overcome compliance and resistance, it is still mandatory to search for the optimal second-line regimen to eradicate H. pylori, with consistent and high efficacy. The evaluation of second or third 'rescue' regimens for these problematic cases seems to be worthwhile. Many clinicians have been using empirical second-line approaches, with either 1- or 2-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy. Because of the H. pylori resistance to metronidazole, it has been shown that extended usage, e.g., for 10 to 14 days, was highly effective in some metronidazole resistant areas,11 and it has been suggested that 2-week metronidazole usage may overcome the negative influence of metronidazole resistance.12 One of the major limitations to this 'rescue' treatment is poor patient compliance due to side effects and complexity of the regimen; thus, even with this treatment, approximately 20% of the patients failed to eradicate H. pylori infection.13,14 The other main reasons for eradication failure were poor patient compliance, resistant bacteria, low gastric pH, and high bacterial load.14,15 Although one previous study showed that 2-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy was more effective than the 1-week treatment without compliance difference,16 there are only few recent studies evaluating the success rate of bismuth-containing quadruple regimens according to duration. Therefore, treatment duration with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy remains still controversial. Furthermore, its feasibility has not been formally tested in many clinical practice settings. In this study, the primary aim was to compare the eradication rate between the 1-week PPI, bismuth salts, tetracycline and metronidazole treatment and the 2-week treatment regimen for the eradication of H. pylori infection, in patients who had already undergone at least one eradication attempt. This prospective, randomized controlled trial compared the efficacy, compliance, and side effects between the 1- and 2-week quadruple regimens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

We prospectively enrolled 169 consecutive H. pylori-positive patients who had already received at least one first line PPI-based triple therapy, (PPI b.i.d., clarithromycin 500 mg b.i.d., and amoxicillin 1 g b.i.d.). They had all been referred to five hospitals during the period from October 2008 to March 2010. Patients were deemed eligible for this study if they were over 18 years of age, and had not taken PPI, antibiotics, bismuth salts, or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for at least 1 month preceding the study. Patients with serious, concomitant illnesses, such as decompensated liver cirrhosis and uremia, or who had undergone previous gastric surgery, were excluded from the study, as were pregnant and lactating women and patients allergic to drugs. All patients gave their informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hallym University Medical Center. The presence of H. pylori after a previous eradication therapy was defined as at least one positive result among the following tests: rapid urease test, histology and 13C urea breath test. A rapid urease test (CLOtest; Delta West, Bentley, Australia) was performed by gastric each two mucosal biopsies from the lesser curvature of the mid antrum and mid body, and histological evidence of H. pylori was obtained by modified Giemsa staining in each two biopsies the lesser and greater curvature of the mid antrum or mid body.

2. Methods

A total 169 patients were randomized at five centers in Korea. The sample size calculation was based on the estimation that a 15% difference in the eradication rates between the 1- and 2-week quadruple therapy would have been clinically relevant. The number of patients required for the study with a two-tailed 5% significance test and a power of 80% was 76 per group. Finally, we calculated that at least 85 patients were required in each group assuming a withdrawal rate of 5%. Two treatment regimens were assigned to two groups, using randomly permuted blocks placed in identical, sequentially numbered blocks. A block size was 4. Investigators were unaware of the block size or treatment allocation. Then, patients were randomly assigned to either 1 or 2 weeks of bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in each disease group, at five hospitals. Independent researcher assigned participants to interventions. Rescue therapy consisted of PPI (pantoprazole 40 mg b.i.d.), tripotassium dicitrate bismuthate 300 mg q.i.d., metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d., and tetracycline 500 mg q.i.d. (BMT). All drugs were taken 1 hour before meals or at night before sleep, and administered for 1 or 2 weeks, according to each group. To assess the eradication, repeated endoscopy with rapid urease test, histological examination, or 13C urea breath tests were performed at 4 to 8 weeks after the end of quadruple therapy. Patients were fasted for 8 hours before 13C-urea breath test. No test meal was given and the pre-dose breath sample was obtained in the bag. Then, 100 mg of 13C-urea powder (UBiTkit™; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in 100 mL of water and administered orally; a second breath sample was collected in the bag 20 minutes later. The cut-off value used was 2.5%. The collected samples were analyzed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (UBiT-IR300®; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.). Eradication was defined as negative results of all rapid urease tests and histology or a negative result of the urea breath test. All patients underwent endoscopy before rescue therapy.

3. Questionnaire

Complete medical history and demographic data were obtained from each patient, including age, sex, body weight, medical history, and history of cigarette smoking and alcohol, coffee or tea consumption before rescue therapy. Smoking was defined as smoking one pack or more per week. Coffee or tea consumption was defined as drinking one cup or more per day. Adverse events and compliance were prospectively evaluated after the completion of therapy. In the 2-week rescue therapy group, patients were re-interviewed on the phone, 1 week after therapy initiation. The adverse events, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and itching were assessed using a 4-point scale system: 0-none; 1-mild (annoying discomfort, but not interfering with daily life); 2-moderate (sufficient discomfort to interfere with daily life); and 3-severe (discomfort resulting in discontinuation of eradication therapy). Compliance was checked by counting unused medication at the end of treatment. Good compliance was defined as taking more than 85% of the total medication. Well and poor compliance was defined as taking 75% to 85% and less than 75% of the total medication, respectively.

4. Statistical analysis

Comparison of treatment effectiveness in the two study groups was performed both using intention to treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analysis. All enrolled patients were included in the ITT analysis and patients without either final 13C urea breath test results or rapid urease test results were classified as failed treatment. The PP analysis excluded patients with unknown H. pylori status following therapy and those with major protocol violations. The differences of H. pylori eradication rates between the two groups and their 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated in both ITT and PP analyses. Demographic characteristics between the two groups were compared by the chi-squared test. Continuous variables were analyzed by the Student's t-test and categorical variables by the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. To evaluate difference in eradication rate according to conditions such as sex, underlying endoscopic finding, smoking and alcohol, Cochran Mantel-Haensel analysis was used. Analysis was performed using the SPSS software version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

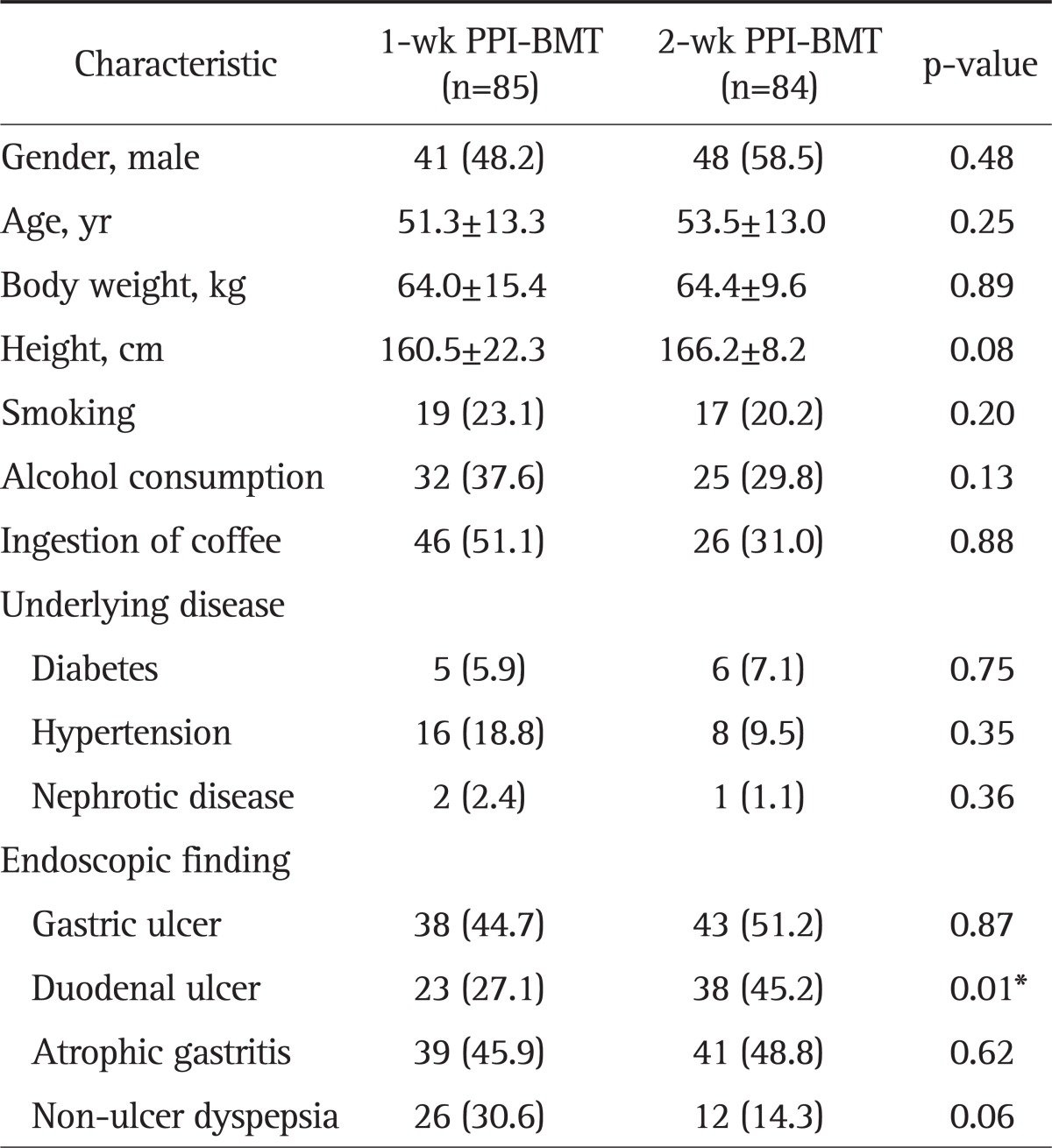

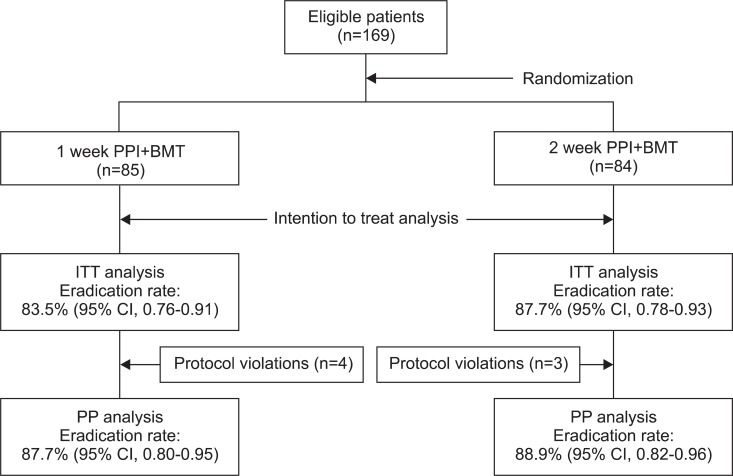

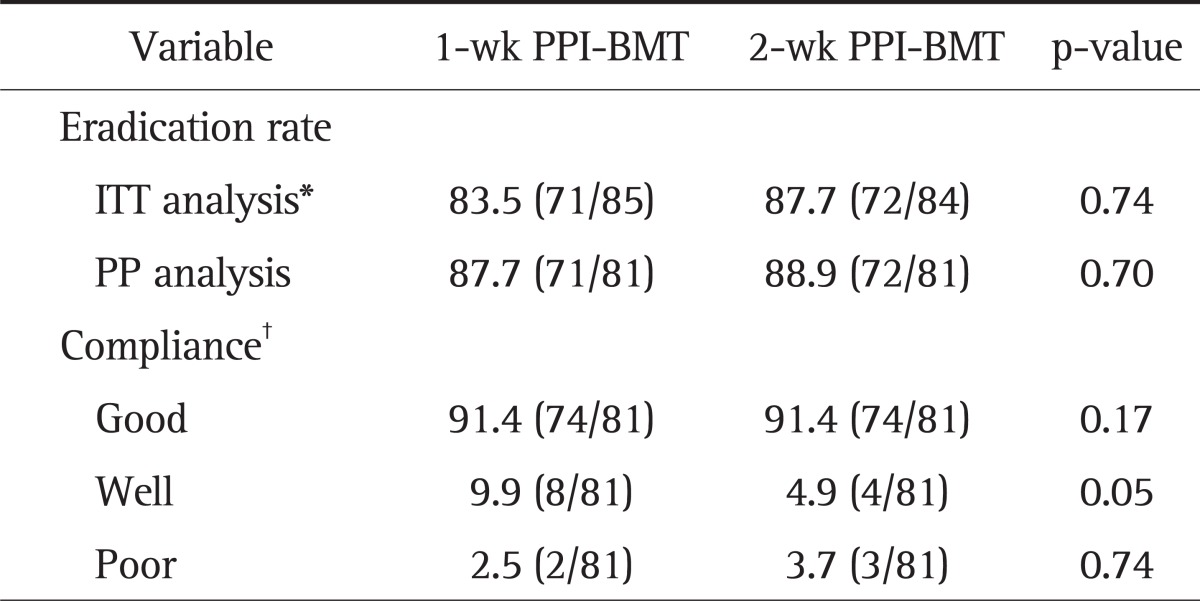

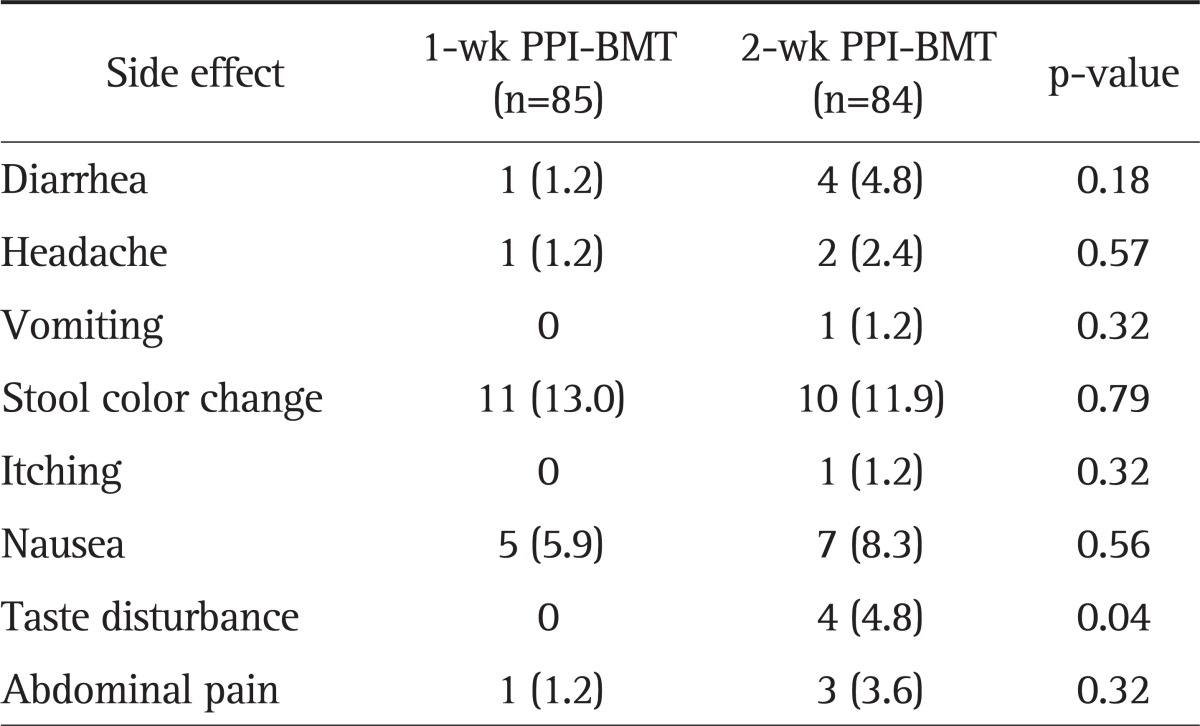

All randomized 169 patients were eligible for ITT analysis. Among these patients, 85 patients received 1-week PPI+BMT and 84 patients received 2-week PPI+BMT. The main demographic and clinical features of 169 patients according to the two treatment arms are shown in Table 1. Demographic characteristics were similar, except for higher proportion of patients with duodenal ulcers in the 2-week PPI+BMT group, as were symptoms at the initial assessment. Overall, seven patients had protocol violations that excluded them from PP analysis. Among these patients, four patients were in the 1-week PPI+BMT treatment group. Their violations were follow-up loss, inadequately taking medicine and discontinuing the therapy due to intolerable side effects. Thus, seven patients were dropped out from PP analysis. Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram of patients progress through the phases of the study. The 1-week PPI+BMT regimen achieved 83.5% (95% CI, 76% to 91%) eradication rate in ITT analysis and 87.7% (95% CI, 80% to 95%) in PP analysis, while the 2-week PPI+BMT regiment obtained 87.7% (95% CI, 78% to 93%) eradication rate in ITT and 88.9% (95% CI, 82% to 96%) in PP analysis. There was no statistically significant difference between the two treatment modalities (Table 2). The compliance rates of the 1-week PPI+MBT group were 91.4% 'good' compliance, 9.9% 'well' compliance and 2.5% 'poor' compliance. In the 2-week PPI+MBT treatment group, the compliance rates were 91.4%, 4.6%, and 3.7%, respectively (Table 2). Overall, 52 patients reported side-effects, i.e., 19 patients (22.4%) in the 1-week PPI+BMT group and 32 patients (38.1%) in the 2-week PPI+BMT group. Diarrhea, headache, vomiting, stool color change, itching, nausea, taste disturbance, and abdominal pain were reported as side effects. There was no statistically significant difference in side effects between the two groups (Table 3). Only one patient from each group withdrew from the study due to significant side effects. The prevalence of side effects was not significantly increased with treatment duration. In both groups, most patients tolerated well the side effects and continued medication with encouragement from the physician, even when the side effects were rather serious.

Table 1.

Demographic Data and Clinical Characteristics of the Two Patient Groups in the Intention to Treat Analysis

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BMT, bismuthate, metronidazole, tetracycline.

*p<0.05.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the phases of the study progress. Eradication rates are presented for both the intention to treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses in the two groups.

PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BMT, bismuthate, metronidazole, and tetracycline; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2.

The Eradication Rate of and Compliance with the 1-Week and 2-Week PPI+BMT Quadruple Rescue Therapy

Data are presented as percentage (number/total number).

PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BMT, bismuthate, metronidazole, and tetracycline; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per-protocol.

*In the ITT analysis, patients without final 13C urea breath test results or rapid urea test results were classified as treatment failures; †Good compliance was defined as taking more than 85% of the total medication. Fair and poor compliance were defined as taking 75% to 85% and less than 75% of the total medication, respectively.

Table 3.

Side Effects of the 1- and 2-Week PPI+BMT Quadruple Rescue Therapy

Data are presented as number (%).

PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BMT, bismuthate, metronidazole, and tetracycline.

DISCUSSION

The use of the quadruple regimen (i.e., PPI+BMT) has been generally suggested as the optimal second-line therapy, after PPI-clarithromycin-amoxicillin failure, and has been therefore recommended as 'rescue' regimen in several guidelines.10,17,18 The Korean Helicobacter Study group recommended either 1- or 2-week quadruple therapy as second-line treatment in cases with initial treatment failure.19 However, there were only few reports directly comparing the 1-week PPI+BMT with 2-week PPI+BMT in prospective, randomized studies. Recently, the result that 2-week bismuth-containing quadruple therapy was more effective than 1-week quadruple therapy as second-line treatment was reported in Korea.16 In that report, the eradication rates were 72/112 (64.3%; 95% CI, 0.504 to 0.830) and 71/92 (77.2%; 95% CI, 0.440 to 0.749) in the 1-week group, compared to 95/115 (82.6%; 95% CI, 1.165 to 2.449) and 88/94 (93.6%; 95% CI, 1.213 to 5.113) in the 2-week group, by ITT therapy (p=0.002) and PP analysis (p=0.001), respectively. In our prospective study, the eradication rates of 1 and 2 weeks groups were 71/85 (83.5%) versus 72/84 (87.7%), and 71/81 (87.7%) versus 72/81 (88.9%), in ITT and PP analyses, respectively. In another Korean study, in which therapeutic durations varied from 7 to 14 days, the eradication rates of second line quadruple therapy have been reported as 54.5% to 76.7% and 70.4% to 83.9%, in ITT and PP analysis, respectively.20-23 In Western countries, some studies have shown the benefit of eradication with prolonged treatment durations,24 but others did not.25 Because there have been only few prospective randomized studies comparing eradication rates between 1 and 2 weeks bismuth containing quadruple therapy, it is not yet known whether a prolonged treatment duration would be beneficial to obtain better eradication rate. In our study, 1 and 2 weeks PPI+BMT groups showed similar eradication rates, contrasting results from a previous Korean study.16 This may be results of the regional or institutional difference in antibiotics resistance. Results of one previous study showed that there was institutional difference in antibiotic resistance of H. pylori, explaining the institutional difference in eradication rates of H. pylori.26 In that study, investigators evaluated whether the prevalence rates of primary antibiotic resistance in H. pylori isolates could be different between two institutions, which are located in the different areas in Korea. They suggested that the resistance to clarithromycin seems to be an important determinant for the eradication by classic triple therapy.

The main causes of treatment failure are thought to be poor patient compliance and bacterial resistance.27-30 In addition, high resistance to metronidazole in Korea31-34 limited the efficacy of metronidazole-containing quadruple therapy as a second-line therapy. Korean data usually came from Seoul, and it might not be representative for the whole Korea. Among the five hospitals in this study, three hospitals were located in Seoul, one in Gyeonggi, and one in the Gangwon province. We could not explain what diffrence eradication rate between patients lived in different areas in this study. This is one of important limits of our study. Although we did not investigate H. pylori culture and antibiotic resistance in each hospital, a regional or institutional difference in H. pylori culture and antibiotic resistance might explain the fact that eradication rate of was not significantly different between the two groups. However, due to this reason, this study has the lack of susceptibility data why PPI+BMT rescue therapy succeeded or failed in 1- and 2-week groups. This could make interpretation difficult in terms of recommendations which duration of rescue therapy is better. Further analysis about the overall use of antibiotics and resistance to antibiotics included in bismuth containing quadruple therapy is warranted to acquire more adequate explanation for this result. It would clarify whether bismuth containing quadruple therapy performed during 2 weeks, rather than one, may overcome metronidazole resistance. Regarding tetracycline resistance, the impact of tetracycline susceptibility has not been well-established.35 The prevalence of H. pylori to tetracycline is very low, except in a few countries, including Korea.36 One study reported that tetracycline resistance was remarkably increased in Korea.16 Our successful eradication rates in patients treated for 1 or 2 weeks with the quadruple regimen, including tetracycline, were similar with previous reports for bismuth containing quadruple therapy. Therefore, it is thought that tetracycline would not be important in H. pylori eradication. Further investigation is needed to understand the effect of tetracycline resistance according to treatment duration. However, the success rate of rescue therapy in this study was lower than desired rate despite giving the drugs for 14 days and may be due to presence of resistance to tetracycline or metronidazole, or to giving the drugs before meals. The other reason underlying treatment failure in H. pylori eradication treatment is low compliance with the available therapeutic regimens,13 since quadruple therapy requires administration of too many tablets and may produce a relatively high rate of side effects. Although we found no significant difference between the two groups in our study, other report showed a rate of 39.6% side effects of bismuth containing quadruple therapy.37 In conclusion, the one week PPI+BMT regimen was as effective as the 2-week PPI+BMT regimen. The discrepancy between our and that from a previous Korean study might be explained by regional difference. Further study should investigate the regional differences in antibiotic resistance and eradication rate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all investigators for collecting data.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1863–1873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Tseng HH, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori prevents ulcer development in patients with ulcer-like functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:195–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillen D, McColl KE. Gastroduodenal disease, Helicobacter pylori, and genetic polymorphisms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1180–1186. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00896-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst PB, Peura DA, Crowe SE. The translation of Helicobacter pylori basic research to patient care. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:188–206. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:187–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, González L, Calvet X, et al. Proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and either amoxycillin or nitroimidazole: a meta-analysis of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1319–1328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gisbert JP, Pajares R, Pajares JM. Evolution of Helicobacter pylori therapy from a meta-analytical perspective. Helicobacter. 2007;12(Suppl 2):50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuccio L, Minardi ME, Zagari RM, Grilli D, Magrini N, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: duration of first-line proton-pump inhibitor based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:553–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923–931. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-12-200806170-00226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischbach LA, van Zanten S, Dickason J. Meta-analysis: the efficacy, adverse events, and adherence related to first-line anti-Helicobacter pylori quadruple therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1071–1082. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filipec Kanizaj T, Katicic M, Skurla B, Ticak M, Plecko V, Kalenic S. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy success regarding different treatment period based on clarithromycin or metronidazole triple-therapy regimens. Helicobacter. 2009;14:29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham DY, Lew GM, Malaty HM, et al. Factors influencing the eradication of Helicobacter pylori with triple therapy. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90095-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houben MH, van de Beek D, Hensen EF, de Craen AJ, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. A systematic review of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: the impact of antimicrobial resistance on eradication rates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1047–1055. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Megraud F, Lamouliatte H. Review article: the treatment of refractory Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1333–1343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BH, Kim N, Hwang TJ, et al. Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy as second-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection: effect of treatment duration and antibiotic resistance on the eradication rate in Korea. Helicobacter. 2010;15:38–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Gomollón F, Sáinz R. Treatment for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Recommendations of the Spanish Consensus Conference. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;114:185–195. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim N, Kim JJ, Choe YH, Kim HS, Kim JI, Chung IS. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:269–278. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.5.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park MJ, Choi IJ, Kim JS, et al. Efficacy of quadruple therapy as retreatment regimen in Helicobacter pylori-positive peptic ulcer disease. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2000;36:457–464. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JH, Cheon JH, Park MJ, et al. The trend of eradication rates of second-line quadruple therapy containing metronidazole for Helicobacter pylori infection: an analysis of recent eight years. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;46:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choung RS, Lee SW, Jung SW, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of quadruple salvage regimen for Helicobacter pylori infection according to the duration of treatment. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung SJ, Lee DH, Kim N, et al. Eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori infection with second-line treatment: non-ulcer dyspepsia compared to peptic ulcer disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1293–1296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baena Díez JM, López Mompó C, Rams Rams F, García Lareo M, Rosario Hernández Ibáñez M, Teruel Gila J. Efficacy of a multistep strategy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: quadruple therapy with omeprazole, metronidazole, tetracycline and bismuth after failure of a combination of omeprazole, clarithromycin and amoxycillin. Med Clin (Barc) 2000;115:617–619. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7753(00)71640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rokkas T, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G, Pistiolas D. Cumulative H. pylori eradication rates in clinical practice by adopting first and second-line regimens proposed by the Maastricht III consensus and a third-line empirical regimen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:21–25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim N, Kim JM, Kim CH, et al. Institutional difference of antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:683–687. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mantzaris GJ, Petraki K, Archavlis E, et al. Omeprazole triple therapy versus omeprazole quadruple therapy for healing duodenal ulcer and eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a 24-month follow-up study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1237–1243. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamouliatte H, Mégraud F, Delchier JC, et al. Second-line treatment for failure to eradicate Helicobacter pylori: a randomized trial comparing four treatment strategies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:791–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laheij RJ, Rossum LG, Jansen JB, Straatman H, Verbeek AL. Evaluation of treatment regimens to cure Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:857–864. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chi CH, Lin CY, Sheu BS, Yang HB, Huang AH, Wu JJ. Quadruple therapy containing amoxicillin and tetracycline is an effective regimen to rescue failed triple therapy by overcoming the antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:347–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim N, Lim CN, Lim SH, et al. Establishment of an Helicobacter pylori-eradication regimen in consideration of drug resistance, recrudescence and reinfection rate of H. pylori. Korean J Med. 1999;56:279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JJ, Reddy R, Lee M, et al. Analysis of metronidazole, clarithromycin and tetracycline resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolates from Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47:459–461. doi: 10.1093/jac/47.4.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eun CS, Han DS, Park JY, et al. Changing pattern of antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korean patients with peptic ulcer diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:436–441. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Kim N, Kim YJ, Song IS. Distribution of antibiotic MICs for Helicobacter pylori strains over a 16-year period in patients from Seoul, South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4843–4847. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4843-4847.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Megraud F, Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:280–322. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00033-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim JM. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Korean patients. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:337–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parente F, Cucino C, Bianchi Porro G. Treatment options for patients with Helicobacter pylori infection resistant to one or more eradication attempts. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:523–528. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]