Abstract

Background:

Testicular germ cell tumour (TGCT) patients are at increased risk of developing a contralateral testicular germ cell tumour (CTGCT). It is unclear whether TGCT treatment affects CTGCT risk.

Methods:

The risk of developing a metachronous CTGCT (a CTGCT diagnosed ⩾6 months after a primary TGCT) and its impact on patient’s prognosis was assessed in a nationwide cohort comprising 3749 TGCT patients treated in the Netherlands during 1965–1995. Standardised incidence ratios (SIRs), comparing CTGCT incidence with TGCT incidence in the general population, and cumulative CTGCT incidence were estimated and CTGCT risk factors assessed, accounting for competing risks.

Results:

Median follow-up was 18.5 years. Seventy-seven metachronous CTGCTs were diagnosed. The SIR for metachronous CTGCTs was 17.6 (95% confidence interval (95% CI) 13.9–22.0). Standardised incidence ratios remained elevated for up to 20 years, while the 20-year cumulative incidence was 2.2% (95% CI 1.8–2.8%). Platinum-based chemotherapy was associated with a lower CTGCT risk among non-seminoma patients (hazard ratio 0.37, 95% CI 0.18–0.72). The CTGCT patients had a 2.3-fold (95% CI 1.3–4.1) increased risk to develop a subsequent non-TGCT cancer and, consequently, a 1.8-fold (95% CI 1.1–2.9) higher risk of death than patients without a CTGCT.

Conclusion:

The TGCT patients remain at increased risk of a CTGCT for up to 20 years. Treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy reduces this risk.

Keywords: contralateral testicular germ cell tumour, chemotherapy, platinum, cumulative incidence, prognosis

Although most testicular germ cell tumour (TGCT) patients present with a single affected testicle, in 0.5–1% bilateral TGCT is diagnosed (Wanderås et al, 1997; Theodore et al, 2004; Fosså et al, 2005; Hentrich et al, 2005). Testicular germ cell tumour patients remain at increased risk of developing a contralateral testicular germ cell tumour (CTGCT) during follow-up (Osterlind et al, 1991; van Leeuwen et al, 1993; Wanderås et al, 1997; Fosså et al, 2005; Andreassen et al, 2011). It remains unclear whether primary treatment, especially platinum-based chemotherapy, affects the risk of developing a metachronous CTGCT. In a previous report from our institute we found a strongly increased CTGCT risk compared with the general population after surgery or radiotherapy but not after chemotherapy (van Leeuwen et al, 1993). Several other studies reported a higher CTGCT risk for seminoma compared with non-seminoma TGCT patients, which may reflect differences in treatment (Che et al, 2002; Theodore et al, 2004; Fosså et al, 2005). However, few studies directly evaluated the effect of TGCT treatment on CTGCT risk, with controversial results (van Basten et al, 1997; Wanderås et al, 1997).

This study assesses long-term CTGCT risk, risk factors for developing a CTGCT and the impact of a CTGCT and its treatment on patient prognosis in a large nationwide cohort of TGCT patients treated in the Netherlands between 1965 and 1995.

Patients and methods

Patient selection and data collection have been described in detail in earlier reports (van Leeuwen et al, 1993; van den Belt-Dusebout et al, 2007). Briefly, TGCT patients were identified through the former Netherlands Committee on Testicular Tumors registry (Zwaveling and Soebhag, 1985) and tumour registries at several referral hospitals (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Daniel den Hoed Cancer Center, University Medical Center Groningen and Amsterdam Medical Center). For this study, an additional 357 patients treated at the Radboud University Medical Center in 1982–1995 were also included.

Data were collected on dates of birth and tumour diagnoses, histology, primary and relapse treatment (radiation fields and chemotherapy regimens), date and cause of death. Medical follow-up regarding TGCT treatment and second malignancies (SMNs) was obtained actively from medical charts, general practitioners and attending physicians, and was complete until at least 1 January 2000, the date of death, or the date of emigration for 90% of all patients (van den Belt-Dusebout et al, 2007). Subsequently, we retrieved data on SMNs, including CTGCTs, diagnosed in the period 1989–2007 from the Netherlands Cancer Registry and dates of death or emigration up to January 2008 from the Dutch Central Bureau for Genealogy and the Dutch municipal administrations.

Treatment

Changes in TGCT treatment after orchiectomy were described in detail previously (van Leeuwen et al, 1993; van den Belt-Dusebout et al, 2007). Briefly, stage I and II seminoma and non-seminoma patients received radiotherapy to the para-aortic and ipsilateral iliacal nodes (30–35 and 40–50 Gy in fractions of 2 Gy, respectively). Since the mid-1980s, radiotherapy dose has been reduced to 26 Gy for seminoma while surveillance became common for stage I non-seminomas. Until the late 1970s treatment for disseminated non-seminomas generally consisted of dactinomycin alone or combined with vincristine, vinblastine or bleomycin. Both disseminated seminomas and non-seminomas were treated primarily with cisplatin, vinblastine and bleomycin (PVB) since 1977 and with bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin (BEP) from the mid-1980s. Besides PVB and BEP several other regimens have been used, mainly within randomised trials. For this study all chemotherapy regimens with cis- or carboplatin were categorised as ‘Platinum-based’ while all other regimens were grouped under ‘Other’.

Statistical analysis

As most relapses occurred early, relapse treatment before a CTGCT was combined with primary treatment. We compared CTGCT incidence with age- and calendar year-specific TGCT incidence rates for the Dutch population, accounting for person-years of observation. Cancer incidence data from the Eindhoven Cancer Registry for 1970–1988 and from the NCR for 1989–2009 were used as reference rates (The Netherlands Cancer Registry: Cancer in figures, 2012).

Standardised incidence ratios (SIR) were calculated as observed over expected number of CTGCTs and absolute excess risks (AER) as the observed minus the expected CTGCT number, divided by person-years at risk, times 10 000. Only metachronous CTGCTs, defined as any CTGCT diagnosed ⩾6 months after the primary TGCT, were analysed. Time at risk therefore started 6 months after TGCT diagnosis and ended at date of CTGCT diagnosis, emigration, death or most recent medical information. Tests for association and linear trend for both SIR and AER were based on Poisson regression models (Breslow and Day, 1987; Boshuizen and Feskens, 2010). Cumulative CTGCT incidence and confidence intervals were estimated in the presence of death as competing risk (Gooley et al, 1999; Choudhury 2002).

Effects of TGCT treatment on metachronous CTGCT risk were quantified using multivariable regression with death as competing risk (Fine and Gray, 1999). To compare the risk of subsequent non-TGCT cancer with and without a prior CTGCT we used a competing risk regression model (death as competing risk) with CTGCT as a time-dependent covariate, allocating follow-up time to the ‘no CTGCT’ group until metachronous CTGCT occurrence. The model also included age at primary TGCT diagnosis and receipt of radiotherapy and chemotherapy for the primary TGCT (or for any recurrence of this cancer before the CTGCT diagnosis). Similarly, we used a Cox model with CTGCT as a time-dependent covariate, to compare survival with and without a CTGCT. This model used attained age as time-scale and also adjusted for age at diagnosis and histology of the primary TGCT, period of treatment and receipt of radiotherapy and chemotherapy for the primary TGCT (or radiotherapy or chemotherapy for any recurrence of this cancer before the CTGCT diagnosis). Three patients with a CTGCT had an invasive non-testis cancer (two stomach cancers and one lung cancer) before the development of their CTGCT, whereas another 396 had an invasive non-testis cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer but no CTGCT. The three patients with a second cancer before their CTGCT were not censored in the analysis of CTGCT risk factors, but were censored in the analysis of survival after a CTGCT and in the analysis of the impact of developing a CTGCT on the risk of an invasive non-testis cancer and the risk of death after a primary TGCT, where the CTGCT was treated as a time-dependent event.

Analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (Stata 11, StataCorp. LP, College Station, TX, USA) and a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The cohort comprised 1716 (45.8%) seminoma and 2033 (54.2%) non-seminoma TGCT patients (Table 1). The majority of seminoma patients (86.9%) received radiotherapy, whereas most non-seminoma patients either received chemotherapy (61.8%) or surgery alone (24.4%). The median follow-up was 18.5 years; 23.7% of the survivors accumulated ⩾25 follow-up years.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Seminoma | Non-seminoma | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| All patients | 1716 | 100.0 | 2033 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||||

| Median age (IQR) | 38.2 (31.7–46.8) | 28.2 (23.3–34.6) | ||

| <30 | 336 | 19.6 | 1176 | 57.9 |

| 30–39 | 636 | 37.1 | 571 | 28.1 |

| 40–49 | 424 | 24.7 | 190 | 9.4 |

| ⩾50 | 320 | 18.7 | 96 | 4.7 |

| Treatment period | ||||

| 1965–1975 | 401 | 23.4 | 374 | 18.4 |

| 1976–1985 | 635 | 37.0 | 835 | 41.1 |

| 1986–1995 | 680 | 39.6 | 824 | 40.5 |

| Stage | ||||

| Stage I | 982 | 57.2 | 749 | 36.8 |

| Stage II | 341 | 19.9 | 520 | 25.6 |

| Stage III/IV | 87 | 5.1 | 473 | 23.3 |

| Stage unknown | 306 | 17.8 | 291 | 14.3 |

| Total treatment a | ||||

| Surgery±RT | 1413 | 82.3 | 775 | 38.1 |

| Platinum-based CT | 222 | 12.9 | 970 | 47.7 |

| Other CT | 81 | 4.7 | 288 | 14.2 |

| Recurrence | ||||

| No | 1598 | 93.1 | 1831 | 90.1 |

| Yes | 118 | 6.9 | 202 | 9.9 |

| Vital status | ||||

| Alive | 1123 | 68.2 | 1419 | 71.3 |

| Dead | 552 | 32.2 | 570 | 28.1 |

| Lost to follow-up | 41 | 2.4 | 44 | 2.2 |

Abbreviations: CT=chemotherapy; IQR=inter quartile range; RT=radiotherapy.

All treatment administered after surgery (orchiectomy with or without retroperitoneal lymph node dissection), including treatment for relapse/recurrence before metachronous CTGCT diagnosis.

Eighty-seven patients, 48 with a primary seminoma and 39 with a non-seminoma TGCT, developed a CTGCT. Ten CTGCTs were diagnosed within 6 months of the primary TGCT (synchronous CTGCT), nine among seminoma (seven of which were also of the seminoma subtype) and one (a seminoma) among non-seminoma patients.

The remaining 77 CTGCTs were diagnosed ⩾6 months after the primary TGCT. The median interval until diagnosis of these metachronous CTGCT did not differ between seminoma and non-seminoma patients (8.5 years, range 0.8–23.9 years) and 63.6% occurred within 10 years of the primary TGCT. Only two metachronous CTGCT were diagnosed after >20 year. Three metachronous CTGCT patients also experienced a relapse, which preceded the CTGCT in all cases. Irrespective of TGCT histology, metachronous CTGCTs were more frequently of the seminoma than of the non-seminoma subtype; 32 (82%) CTGCTs among seminoma and 23 (61%) CTGCTs among non-seminoma patients were seminomas.

Relative risk compared with the general population

Overall, the incidence of metachronous CTGCT in our cohort was 17.6 (95% CI 13.9–22.0) times higher than the expected TGCT incidence based on general population rates (Table 2). The SIRs did not vary by age at TGCT diagnosis (Pheterogeneity=0.19) or follow-up duration (Ptrend=0.13, restricted to the first 25 years of follow-up). The SIR was lower for patients diagnosed in the period 1976–1985 and 1986–1995 compared with patients diagnosed during 1965–1975 (1976–1985 vs 1965–1975: relative risk (RR) 0.38, P=0.001; 1986–1995 vs 1965–1975: RR 0.32, P<0.001).

Table 2. Number of patients (N), observed number (O), SIR, AER per 10 000 person-years and 10-, and 20-year cumulative incidence (%) for metachronous CTGCTs according to histological type age, period of diagnosis and treatment of the primary TGCT.

| At risk at 6 months | Person-time (years) | All CTGCT a | SIR (95% CI) | AER (95% CI) | At risk at 10 years | CTGCT at 10 years | 10-year cumulative incidence (95% CI) | At risk at 20 years | CTGCT at 20 years | 20-year cumulative incidence (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seminoma and non-seminoma combined | |||||||||||

| All patients | 3608 | 63 635 | 77 | 17.6 (13.9–22.0) | 11.4 (8.9–14.4) | 2963 | 49 | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 1554 | 75 | 2.2 (1.8–2.8) |

| Age | |||||||||||

| <30 | 1451 | 25 633 | 40 | 14.9 (10.6–20.3) | 14.6 (10.1–20.2) | 1198 | 23 | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | 640 | 40 | 3.0 (2.2–4.1) |

| 30–39 | 1180 | 21 716 | 26 | 20.8 (13.6–30.5) | 11.4 (7.2–17.0) | 995 | 20 | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 536 | 24 | 2.2 (1.4–3.2) |

| ⩾40 | 977 | 16 286 | 11 | 25.3 (12.6–45.3) | 6.5 (3.1–11.8) | 770 | 6 | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 378 | 11 | 1.2 (0.6–2.0) |

| Treatment period | |||||||||||

| 1965–1975 | 725 | 14 633 | 22 | 41.1 (25.8–62.3) | 14.7 (9.0–22.4) | 490 | 14 | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | 409 | 21 | 2.9 (1.9–4.3) |

| 1976–1985 | 1403 | 28 168 | 27 | 15.8 (10.4–23.0) | 9.0 (5.7–13.3) | 1184 | 13 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 985 | 26 | 1.9 (1.3–2.7) |

| 1986–1995 | 1480 | 20 834 | 28 | 13.2 (8.7–19.0) | 12.4 (7.9–18.4) | 1289 | 22 | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 160 | 28 | 2.0 (1.4–2.9) |

| Total treatmentb | |||||||||||

| Surgeryc | 2127 | 41 274 | 62 | 25.8 (19.7–33.0) | 14.4 (10.9–18.7) | 1859 | 40 | 1.9 (1.4–2.6) | 1055 | 60 | 3.0 (2.3–3.9) |

| Platinum-based CTc | 1149 | 18 182 | 13 | 7.5 (4.0–12.9) | 6.2 (2.9–11.3) | 950 | 8 | 0.7 (0.3–1.3) | 372 | 13 | 1.2 (0.7–1.2) |

| Other CTc | 332 | 4179 | 2 | 8.5 (1.0–30.7) | 4.2 (0.2–16.7) | 154 | 1 | 0.3 (0.0–1.6) | 127 | 2 | 0.6 (0.1–2.1) |

| Follow-up interval (years)d,e | |||||||||||

| 0.5–4 | 3608 | 14 817 | 24 | 21.2 (13.6–31.5) | 15.4 (9.6–23.3) | ||||||

| 5–9 | 3136 | 15 338 | 25 | 19.7 (12.8–29.1) | 15.5 (9.7–23.2) | ||||||

| 10–14 | 2963 | 13 416 | 17 | 16.7 (9.7–26.7) | 11.9 (6.6–19.5) | ||||||

| 15–19 | 2313 | 9747 | 9 | 15.7 (7.2–29.8) | 8.6 (3.6–16.9) | ||||||

| 20–24 | 1554 | 5888 | 2 | 7.8 (0.9–28.2) | 3.0 (−0.2 to 11.8) | ||||||

| Seminoma | |||||||||||

| All patients | 1675 | 30 531 | 39 | 24.9 (17.7–34.0) | 12.3 (8.6–17.0) | 1413 | 25 | 1.5 (1.0–2.2) | 744 | 37 | 2.4 (1.7–3.2) |

| Age | |||||||||||

| <30 | 323 | 6060 | 13 | 22.5 (12.0–38.5) | 20.5 (10.5–35.7) | 280 | 8 | 2.5 (1.2–4.7) | 156 | 13 | 4.3 (2.4–7.0) |

| 30–39 | 630 | 12 074 | 17 | 25.7 (15.0–41.1) | 13.5 (7.7–22.0) | 554 | 12 | 1.9 (1.1–3.3) | 294 | 15 | 2.6 (1.5–4.2) |

| ⩾40 | 722 | 12 397 | 9 | 27.4 (12.5–52.0) | 7.0 (3.1–13.5) | 579 | 5 | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 294 | 9 | 1.3 (0.6–2.4) |

| Treatment period | |||||||||||

| 1965–1975 | 393 | 8880 | 14 | 48.6 (26.6–81.6) | 15.4 (8.3–26.1) | 306 | 7 | 1.8 (0.8–3.5) | 252 | 13 | 3.3 (1.9–5.4) |

| 1976–1985 | 613 | 12 381 | 11 | 20.3 (10.1–36.2) | 8.4 (4.0–15.5) | 534 | 7 | 1.2 (0.5–2.3) | 416 | 10 | 1.7 (0.9–3.0) |

| 1986–1995 | 669 | 9270 | 14 | 19.9 (10.4–31.9) | 14.3 (7.5–24.5) | 573 | 11 | 1.7 (0.9–2.9) | 76 | 14 | 2.3 (1.3–3.7) |

| Total treatmentb | |||||||||||

| Surgeryc | 1387 | 26 654 | 37 | 27.8 (19.6–38.6) | 13.4 (9.3–18.6) | 1213 | 24 | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 673 | 35 | 2.7 (1.9–3.7) |

| Platinum-based CTc,f | 209 | 3148 | 1 | 4.9 (0.1–27.5) | 2.5 (−0.6 to 17.1) | 172 | 0 | 0.0 | 51 | 1 | 0.5 (0.0–2.6) |

| Other CTc | 79 | 729 | 1 | 29.8 (0.8–165.8) | 13.2 (−0.1 to 75.9) | 28 | 1 | 1.3 (0.1–6.1) | 20 | 1 | 1.3 (0.1–6.1) |

| Follow-up interval (years)d,e | |||||||||||

| 0.5–4 | 1675 | 7123 | 13 | 27.9 (14.8–47.7) | 17.6 (9.1–30.6) | ||||||

| 5–9 | 1515 | 7388 | 12 | 25.9 (13.4–45.3) | 15.6 (7.8–27.7) | ||||||

| 10–14 | 1413 | 6342 | 9 | 27.0 (12.3–51.2) | 13.7 (6.0–26.4) | ||||||

| 15–19 | 1080 | 4585 | 3 | 16.9 (3.5–49.4) | 6.2 (1.0–18.7) | ||||||

| 20–24 | 744 | 2789 | 2 | 24.6 (3.0–89.0) | 6.9 (0.6–25.6) | ||||||

| Non-seminoma | |||||||||||

| All patients | 1933 | 33 104 | 38 | 13.6 (9.6–18.6) | 10.6 (7.3–14.9) | 1550 | 24 | 1.3 (0.8–1.8) | 810 | 38 | 2.2 (1.5–2.9) |

| Age | |||||||||||

| <30 | 1128 | 19 573 | 27 | 12.8 (8.6–19.1) | 12.7 (8.0–19.0) | 918 | 15 | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 484 | 27 | 2.7 (1.8–3.9) |

| 30–39 | 550 | 9641 | 9 | 15.3 (7.0–29.5) | 8.7 (3.7–17.1) | 441 | 8 | 1.5 (0.7–2.8) | 242 | 9 | 1.7 (0.8–3.0) |

| ⩾40 | 255 | 3890 | 2 | 18.9 (2.3–68.2) | 4.9 (0.4–18.3) | 191 | 1 | 0.4 (0.0–2.0) | 84 | 2 | 0.8 (0.2–2.6) |

| Treatment period | |||||||||||

| 1965–1975 | 332 | 5573 | 8 | 32.4 (14.0–63.8) | 13.5 (5.6–27.0) | 184 | 7 | 2.1 (0.9–4.1) | 157 | 8 | 2.4 (1.1–4.5) |

| 1976–1985 | 790 | 15 787 | 16 | 13.7 (7.8–22.3) | 9.4 (5.1–15.7) | 650 | 6 | 0.8 (0.3–1.6) | 569 | 16 | 2.1 (1.2–3.3) |

| 1986–1995 | 811 | 11 564 | 14 | 10.1 (5.5–16.9) | 10.9 (5.4–19.1) | 716 | 11 | 1.4 (0.7–2.4) | 84 | 14 | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) |

| Total treatmentb | |||||||||||

| Surgeryc | 740 | 14 620 | 25 | 23.2 (15.0–34.3) | 16.4 (10.3–24.5) | 646 | 16 | 2.2 (1.3–3.5) | 382 | 25 | 3.7 (2.4–5.3) |

| Platinum-based CTc,f | 940 | 15 034 | 12 | 7.9 (4.1–13.7) | 7.0 (3.1–12.9) | 778 | 8 | 0.9 (0.4–1.6) | 321 | 12 | 1.4 (0.7–2.3) |

| Other CTc | 253 | 3450 | 1 | 5.0 (0.1–27.6) | 2.3 (−0.5 to 15.6) | 126 | 0 | 0.0 | 107 | 1 | 0.4 (0.0–2.1) |

| Follow-up interval (years)d,e | |||||||||||

| 0.5–4 | 1993 | 7694 | 11 | 16.5 (8.2–29.5) | 13.4 (6.3–24.7) | ||||||

| 5–9 | 1621 | 7950 | 13 | 16.2 (8.6–27.6) | 15.3 (7.7–27.0) | ||||||

| 10–14 | 1550 | 7075 | 8 | 11.7 (5.0–23.0) | 10.3 (3.9–21.3) | ||||||

| 15–19 | 1233 | 5162 | 6 | 15.2 (5.6–33.0) | 10.9 (3.5–11.3) | ||||||

| 20–24 | 810 | 3099 | 0 | 0.0 (0.0–21.1) | −0.4 (−0.4 to 24.7) | ||||||

Abbreviations: AER=absolute excess risk; 95% CI=95% confidence interval; CTGCT=contralateral testicular germ cell tumour; CT=chemotherapy; SIR=standardised incidence ratio; TGCT=testicular germ cell tumour.

Includes three patients, two seminoma and one non-seminoma, with a non-testis second cancer (two stomach cancers, treated with surgery only, and one lung cancer) before the CTGCT diagnosis.

Includes treatment for relapse/recurrence before metachronous CTGCT diagnosis.

With or without radiotherapy.

Number at risk at begin of interval.

Person-time in follow-up interval ⩾25 years: 2305 for seminoma and 2123 years for non-seminoma (4428 for combined group).

Two patients with 2xBEP (Bleomycin, Etoposide, Cisplatin), one patient with 3xBEP+1xEP (Etoposide, Cisplatin), four patients with 4xBEP, one patient with 4xEP, one patient with 4xCEB (Carboplatin, Etoposide, Bleomycin), one patient with 4xVIP (Etoposide, Ifosfamide, Cisplatin), three patients with 4xPVB (Cisplatin, Vinblastin, Bleomycin).

The SIR was 24.9 after a seminoma and 13.6 after a non-seminoma TGCT (seminoma vs non-seminoma: RR 1.84, P=0.008). The SIR was significantly lower for non-seminoma patients treated with chemotherapy (SIR 7.6, 95% CI 4.3–12.6) compared with patients treated without chemotherapy (chemotherapy vs no chemotherapy: RR 0.30, P<0.001). This association remained after adjusting for period of diagnosis and follow-up interval (chemotherapy vs no chemotherapy: RR 0.34, P<0.001, data not shown). For non-seminoma patients who received chemotherapy the median time until metachronous CTGCT was 9.1 years compared with 8.2 years for those treated without chemotherapy (P=0.45).

Absolute excess risk compared with the general population

We observed 11.4 excess CTGCTs (95% CI 8.9–14.4) for every 1000 patients followed for 10 years (Table 2). The AER decreased with age for seminoma (Ptrend=0.015) and, nonsignificantly, for non-seminoma patients (Ptrend=0.067), but the number of events in the age category ⩾40 years was very small among the non-seminoma patients. The AER did not vary by treatment period for either seminoma or non-seminoma. The AER did vary with primary treatment among non-seminoma patients (Pheterogeneity <0.001), with a lower AER for patients treated with chemotherapy (AER 5.8, 95% CI 2.9–10.2) compared with patients treated without chemotherapy (AER chemotherapy vs no chemotherapy: P=0.001).

Cumulative incidence

The cumulative incidence of metachronous CTGCT was 1.4% (95% CI 1.0–1.8%) after 10 years and 2.2% (95% CI 1.8–2.8%) after 20 years of follow-up (Table 2). Cumulative incidence increased at a fairly constant rate during the follow-up and reached a plateau after 20 years of follow-up; no CTGCT was diagnosed after the 24th year of follow-up.

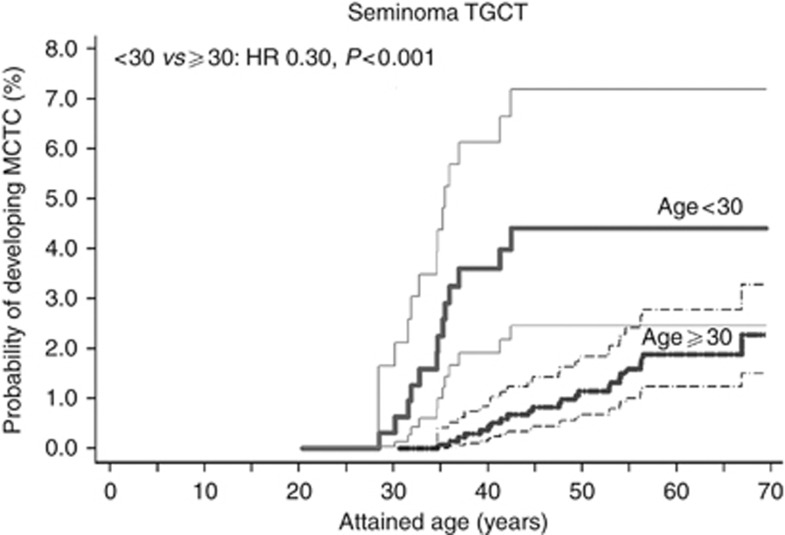

Among seminoma patients, only age at diagnosis was found to be associated with CTGCT cumulative incidence. At 20 years of follow-up, seminoma patients <30 years had a cumulative incidence of 4.3% (95% CI 2.4–7.0%), but incidence decreased for patients who were older at TGCT diagnosis (hazard ratio (HR) per 10-year increase: 0.47, 95% CI 0.26–0.84, data not shown). Figure 1 shows the cumulative incidence by attained age according to age at diagnosis (<30 years vs ⩾30 years) for seminoma patients. The CTGCT incidence increased much more rapid by attained age for younger patients (HR 0.30 for ⩾30 years vs <30 years, P<0.001).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence with 95% CIs of metachronous CTGCTs for patients with a seminoma TGCT by attained age, according to age at diagnosis (<30 vs ⩾30 years).

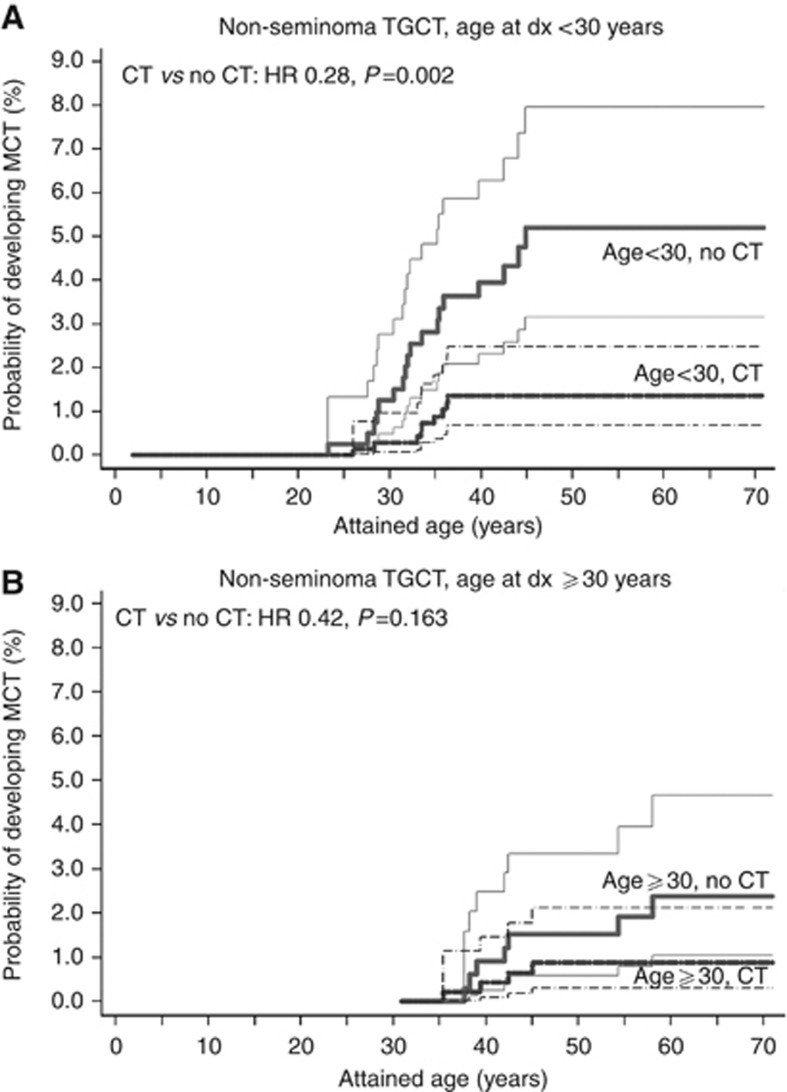

Chemotherapy for non-seminoma TGCT was associated with a significantly lower cumulative CTGCT incidence (Figure 2). However, although receipt of chemotherapy was associated with a >3-fold reduction in cumulative CTGCT incidence (HR 0.28 for chemotherapy vs no chemotherapy, P<0.001) among patients <30 years, the reduction appeared slightly more limited for patients ⩾30 years at diagnosis (chemotherapy vs no chemotherapy: HR 0.42, P=0.16). In multivariable analysis, period of diagnosis did not affect CTGCT risk, whereas older age at diagnosis was associated with a slightly lower CTGCT risk. Platinum-based chemotherapy was associated with a lower CTGCT risk among non-seminoma patients (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.19–0.77; Table 3). Although only based on two CTGCT, non-platinum regimens appeared also associated with lower CTGCT risk.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence with 95% CIs of CTGCTs for patients with a non-seminoma TGCT by attained age, according to treatment with and without chemotherapy and age at diagnosis (A: <30 years; B: ⩾30 years).

Table 3. Multivariate regression analysis of risk factors for the occurrence of metachronous CTGCTs during follow-up (death as competing risk).

| Non-seminoma TGCT only | All TGCTs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Model 1

|

Model 2

|

||||||||

| Risk factor | HR | 95% CI | P -value | HR | 95% CI | P -value | HR | 95% CI | P -value |

| Agea | 0.75 | 0.55–1.00 | 0.049 | 0.74 | 0.55–1.00 | 0.053 | 0.67 | 0.54–0.83 | <0.001 |

| Histology | — | 0.683 | |||||||

| Seminoma | — | — | — | — | — | 1.00 | Ref | ||

| Non-seminoma | — | — | — | — | — | 0.89 | 0.52–1.52 | ||

| Chemotherapy b | 0.001 | — | — | ||||||

| No | 1.00 | Ref | — | — | — | — | |||

| Yes | 0.31 | 0.16–0.60 | — | — | — | — | |||

| Chemotherapy b | — | 0.003 | <0.001 | ||||||

| None | — | — | 1.00 | Ref | 1.00 | Ref | |||

| Platinum-based CT | — | — | 0.37 | 0.18–0.72 | 0.34 | 0.18–0.63 | |||

| Other CT | — | — | 0.11 | 0.01–0.78 | 0.17 | 0.04–0.72 | |||

Abbreviations: 95% CI=95% confidence interval; CTGCT=contralateral testicular germ cell tumour; CT=chemotherapy; HR=(subdistribution) hazard ratio; TGCT=testicular germ cell tumour.

Model 1: chemotherapy (CT) entered in the model as yes vs no.

Model 2: chemotherapy (CT) entered in the model as platinum-based CT or other CT (vs none).

Age, centred to the mean, continuous, every 10-year increase.

Includes treatment for relapse/recurrence before metachronous CTGCT diagnosis.

Association of metachronous CTGCT with survival

The 5- and 10-year overall survival rates after metachronous CTGCT diagnosis for the 74 patients without a prior non-testis second cancer were 93.0% (95% CI 84.3–97.1) and 86.1% (95% CI 74.7–92.6), respectively. Median age at time of death for deceased patients was 49.7 years (range 33–67 years). Only 2 of these 74 CTGCT patients died directly due to disseminated testicular cancer, whereas 9 other CTGCT patients died due to a non-testis second cancer (Supplementary Table S1). Thirteen of these CTGCT patients (22.1%) had at least one other non-TGCT secondary cancer after their primary TGCT. Patients with a metachronous CTGCT had a 2.3 times (95% CI 1.3–4.1, P=0.006) higher risk of developing a subsequent non-TGCT invasive cancer (adjusted for age, chemotherapy and radiotherapy for primary TGCT; data not shown). On the basis of 16 deaths among the 74 CTGCT patients without a prior non-testis second cancer, patients with a CTGCT also had a 1.8 times higher risk (95% CI 1.1–2.9, P=0.026; data not shown) of death than patients who did not develop a CTGCT.

Discussion

In this large cohort study TGCT patients had an almost 18-fold increased risk to develop a metachronous CTGCT compared with the Dutch male population. When considering that TGCT-survivors have only one testicle at risk for CTGCTs, while the reference rates for the general population concern cancer in any of two testes, the risk expressed in testis-years could even be twice as high. The 20-year cumulative CTGCT incidence reached 2.2%, indicating that conditional on surviving, about one in every 45 TGCT patients will develop a CTGCT within 20 years of their primary TGCT. Non-seminoma TGCT treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy was associated with a lower CTGCT risk. A CTGCT diagnosis was associated with worse prognosis, mostly due to deaths from subsequent non-TGCT malignancies.

This study is to our knowledge the largest cohort study on CTGCT risk with complete treatment data and complete follow-up for CTGCT. Our analysis of CTGCT risk was based on all treatment received before CTGCT diagnosis, which allows reliable assessment of the effect of treatment on CTGCT risk. In studies based on data from population-based cancer registries, treatment misclassification is a common problem, either due to underreporting of chemotherapy in initial treatment or due to omission of salvage treatment, thus limiting conclusions regarding the association of TGCT treatment with CTGCT risk (Osterlind et al, 1991; Fosså et al, 2005; Andreassen et al, 2011).

Testicular intraepithelial neoplasms (TINs) are considered precursor lesions for seminoma and non-seminoma TGCT. In a Danish study, contralateral testicle biopsies of 500 TGCT patients revealed contralateral TIN lesions in 5.4% (von der Maase et al, 1986). Fifty percent of the patients with a TIN lesion, who did not receive chemotherapy, developed an invasive TGCT within 5 years, whereas none of the patients who received platinum-based chemotherapy did so, suggesting that platinum-based chemotherapy eradicated TIN lesions. Nonetheless, Greist et al (1984) found residual carcinoma in the removed testes of 3 out of 20 patients who underwent orchiectomy after platinum-based chemotherapy for disseminated TGCT. Recently, Kleinschmidt et al (2009) reported persistent TIN after rebiopsy among 5 out of 11 patients with a primary TIN who had received platinum-based chemotherapy, 2 of whom later developed an invasive TGCT. The Danish group also showed that among 33 patients with disseminated TGCT and a contralateral TIN lesion, all treated with chemotherapy (BEP 26, PVB 6, other 1), 4 patients still developed a CTGCT (Christensen et al, 1998). Other studies also reported CTGCT among patients treated with cisplatinum-containing chemotherapy (Wanderås et al, 1997; Theodore et al, 2004; Hentrich et al, 2005; van den Belt-Dusebout et al, 2007). In our study, 12 of the 77 metachronous CTGCT were diagnosed in non-seminoma patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (PVB 3 patients, BEP 7 patients, EP 1 patient, VIP 1 patient, CEB 1 patient). Therefore, it appears that platinum-based chemotherapy does not completely block the development of CTGCT.

Our study does not lend support to delayed CTGCT development after platinum-based chemotherapy, as postulated by Christensen et al (1998). With a median follow-up of 18.5 years we found no difference in the distribution of CTGCT by follow-up time between non-seminoma patients treated with or without chemotherapy (9.1 vs 8.2 years). The occurrence of metachronous CTGCTs after >10 years of follow-up (36% of CTGCTs in our cohort) proved to be no rare event. Similarly, a study among Norwegian males treated at the Radium Hospital reported that 17% of all CTGCTs were diagnosed after ⩾10 years, whereas in a US study 30% of all CTGCTs were diagnosed after ⩾10 years of follow-up (Wanderås et al, 1997; Che et al, 2002). Assuming that all CTGCTs derive from a pre-existing TIN, that the prevalence of TIN is 5% (based on biopsy studies) and that our estimate of the 10-year cumulative incidence (2.2%) is correct, we would expect that the risk of progression to invasive cancer within 5 years would be <50% currently reported (von der Maase et al, 1986; Dieckmann et al, 2007).

Incidence patterns for metachronous CTGCTs by age group appear to mimic incidence patterns of de novo TGCTs. Although the SIR for CTGCT did not differ by age at TGCT diagnosis, the cumulative incidence decreased with older age at TGCT diagnosis. Although a decreasing CTGCT risk with older age at primary TGCT diagnosis has been observed in several other studies (Wanderås et al, 1997; Theodore et al, 2004; Fosså et al, 2005), no good explanation for this finding has been given. One could speculate that patients who develop testicular cancer later in life are less likely to harbour premalignant cells in the contralateral testis or that a lower fraction of contralateral TIN lesions transforms into invasive tumour among older patients.

The occurrence of a CTGCT appeared to affect patient’s prognosis in our cohort. This may partly reflect the impact of additional CTGCT treatment on late treatment complications, especially non-testis second cancers, as suggested by the two-fold risk increase for a non-testis second cancer among patients with a CTGCT compared with patients without a CTGCT in our study.

In contrast with our results, Fosså et al (2005) previously found no indication that prognosis for a TGCT patient was compromised by the diagnosis of a metachronous CTGCT and even found a slightly lower risk of death for patients with a CTGCT (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.45–1.26). The cohort studied by Fosså et al was diagnosed in a more recent time period; 86% of all included patients in their study were diagnosed with a primary TGCT since 1983. In our cohort 49% of all patients were diagnosed before 1983, in a period in which higher radiation doses and more extensive radiation fields were used.

A potential weakness of our study is that we did not collect information on a history of testicular maldescent, testicular trauma, infertility, testicular atrophy or removal of a testis due to trauma or maldescent. Although these factors could be associated with the risk of developing a CTGCT, they are unlikely to be associated with treatment for the primary testicular cancer and will therefore not confound the reduced risk estimate of CTGCT, which we observed among patients treated with (platinum-based) chemotherapy.

Clinicians can use the results of our study to inform and reassure patients under long-term follow-up about their very low remaining risk to develop a CTGCT. In addition, patients treated with chemotherapy can be informed that albeit they have a very low risk to develop a CTGCT, the risk is not absent. On the basis of our results clinicians should be aware that especially young seminoma patients and young non-seminoma patients, not treated with chemotherapy, have a relatively high risk to develop a CTGCT, reaching about 4%, 20 years after the primary TGCT.

Conclusions

Treatment of non-seminoma TGCT with platinum-based chemotherapy is associated with a markedly lower CTGCT risk. The CTGCT risk remains elevated for at least 20 years, at which time the cumulative incidence reaches 2.2%.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant numbers NKI 98-1833, NKI 04-3068) and by the Lance Armstrong Foundation. We thank O Visser and I de Hoop for providing data on second cancers from the Netherlands Cancer registry. We are indebted to the many physicians from throughout the Netherlands, who for close to 20 years now provided us with follow-up data for our studies.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Presented at the joint ECCO 15 – 34th ESMO Multidisciplinary Congress and the 7th Copenhagen workshop on CIS testis and germ cell cancer.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Andreassen KE, Grotmol T, Cvancarova MS, Johannesen TB, Fosså SD (2011) Risk of metachronous contralateral testicular germ cell tumors: a population-based study of 7,102 Norwegian patients (1953–2007). Int J Cancer 129: 2867–2874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshuizen HC, Feskens EJ (2010) Fitting additive Poisson models. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 7: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research: Volume II – The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies. IARC Scientific Publications: Lyon, (1987) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che M, Tamboli P, Ro JY, Park DS, Ro JS, Amato RJ, Ayala AG (2002) Bilateral testicular germ cell tumors: twenty-year experience at M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Cancer 95: 1228–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury JB (2002) Non-parametric confidence interval estimation for competing risks analysis: application to contraceptive data. Stat Med 21: 1129–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen TB, Daugaard G, Geertsen PF, von der Maase H (1998) Effect of chemotherapy on carcinoma in situ of the testis. Ann Oncol 9: 657–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann KP, Kulejewski M, Pichlmeier U, Loy V (2007) Diagnosis of contralateral testicular intraepithelial neoplasia (TIN) in patients with testicular germ cell cancer: systematic two-site biopsies are more sensitive than a single random biopsy. Eur Urol 51: 175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Amer Statist Assoc 94: 496–509 [Google Scholar]

- Fosså SD, Chen J, Schonfeld SJ, McGlynn KA, McMaster ML, Gail MH, Travis LB (2005) Risk of contralateral testicular cancer: a population-based study of 29,515 U.S. men. J Natl Cancer Inst 97: 1056–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE (1999) Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med 18: 695–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greist A, Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Donohue JP, Rowland RG (1984) Pathologic findings at orchiectomy following chemotherapy for disseminated testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 2: 1025–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentrich M, Weber N, Bergsdorf T, Liedl B, Hartenstein R, Gerl A (2005) Management and outcome of bilateral testicular germ cell tumors: twenty-five year experience in Munich. Acta Oncol 44: 529–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmidt K, Dieckmann KP, Georgiew A, Loy V, Weissbach L (2009) Chemotherapy is of limited efficacy in the control of contralateral testicular intraepithelial neoplasia in patients with germ cell cancer. Oncology 77: 33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterlind A, Berthelsen JG, Abildgaard N, Hansen SO, Hjalgrim H, Johansen B, Munck-Hansen J, Rasmussen LH (1991) Risk of bilateral testicular germ cell cancer in Denmark: 1960–1984. J Natl Cancer Inst 83: 1391–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Netherlands Cancer Registry: Cancer in figures (2012) Utrecht, the Netherlands, Association of Comprehensive Cancer Centres. http://www.cijfersoverkanker.nl/

- Theodore Ch, Terrier-Lacombe MJ, Laplanche A, Benoit G, Fizazi K, Stamerra O, Wibault P (2004) Bilateral germ-cell tumours: 22-year experience at the Institut Gustave Roussy. Br J Cancer 90: 55–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Basten JP, Hoekstra HJ, van Driel MF, Sleijfer DT, Droste JH, Schraffordt Koops H (1997) Cisplatin-based chemotherapy changes the incidence of bilateral testicular cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 4: 342–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Belt-Dusebout AW, de Wit R, Gietema JA, Horenblas S, Louwman MW, Ribot JG, Hoekstra HJ, Ouwens GM, Aleman BM, van Leeuwen FE (2007) Treatment-specific risks of second malignancies and cardiovascular disease in 5-year survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 4370–4378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen FE, Stiggelbout AM, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Noyon R, Eliel MR, van Kerkhoff EH, Delemarre JF, Somers R (1993) Second cancer risk following testicular cancer: a follow-up study of 1,909 patients. J Clin Oncol 11: 415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Maase H, Rørth M, Walbom-Jørgensen S, Sørensen BL, Christophersen IS, Hald T, Jacobsen GK, Berthelsen JG, Skakkebaek NE (1986) Carcinoma in situ of contralateral testis in patients with testicular germ cell cancer: study of 27 cases in 500 patients. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 293: 1398–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanderås EH, Fosså SD, Tretli S (1997) Risk of a second germ cell tumor after treatment of a primary germ cell tumor in 2201 Norwegian male patients. Eur J Cancer 33: 244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaveling A, Soebhag R (1985) Testicular tumors in the Netherlands. Cancer 55: 1612–1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.