Abstract

The immediate-early gene Arc (activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) is provocative in the context of neuroplasticity because of its experience-dependent regulation and mRNA transport to and translation at activated synapses. Normal rats have more preproenkephalin-negative (ppe-neg; presumed striatonigral) neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA than ppe-positive (ppe-pos; striatopallidal) neurons, despite equivalent numbers of these neurons showing novelty-induced transcriptional activation of Arc. Furthermore, rats with partial monoamine loss induced by methamphetamine (METH) show impaired Arc mRNA expression in both ppe-neg and ppe-pos neurons relative to normal animals following response-reversal learning. In this study, Arc expression induced by exposure to a novel environment was used to assess transcriptional activation and cytoplasmic localization of Arc mRNA in striatal efferent neuron subpopulations subsequent to METH-induced neurotoxicity. Partial monoamine depletion significantly altered Arc expression. Specifically, basal Arc expression was elevated, but novelty-induced transcriptional activation was abolished. Without novelty-induced Arc transcription, METH-pretreated rats also had fewer neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression, with the effect being greater for ppe-neg neurons. Thus, METH-induced neurotoxicity substantially alters striatal efferent neuron function at the level of Arc transcription, suggesting a long-term shift in basal ganglia neuroplasticity processes subsequent to METH-induced neurotoxicity. Such changes potentially underlie striatally-based learning deficits associated with METH-induced neurotoxicity.

Keywords: methamphetamine, dopamine, Arc/Arg 3.1, striatum, immediate-early gene

Introduction

Methamphetamine (METH) is a highly addictive psychostimulant that can induce substantial forebrain dopamine (DA) and serotonin depletions when administered at high doses (Wagner et al. 1980, Woolverton et al. 1989). While METH-induced monoamine depletions are significantly less than those observed in Parkinson’s disease, these partial depletions lead to impairments in basal ganglia-mediated behavioral and cognitive abilities in both rodents and humans (Chapman et al. 2001, Kalechstein et al. 2003, Volkow et al. 2001, Johanson et al. 2006). Furthermore, recent data show that individuals with a history of methamphetamine or other amphetamine abuse are more likely to develop Parkinsonism (Callaghan et al. 2012), suggesting that METH exposure may be associated with a significant preclinical period of partial striatal DA loss and associated consequences.

The bases for the cognitive and behavioral sequelae of METH-induced partial DA loss are unknown. Approximately 95% of neurons in striatum are medium spiny neurons, and these efferent neurons can be divided into two equal subpopulations: striatonigral “direct” pathway neurons and striatopallidal “indirect” pathway neurons (Wichmann & DeLong 1996, Obeso et al. 1997, Grillner et al. 2005). These efferent neurons can be phenotypically differentiated at the cell body level by their selective expression of neuropeptides: striatopallidal neurons express preproenkephalin (ppe-pos), whereas striatonigral neurons do not (ppe-neg (Gerfen & Young 1988)). Striatonigral neurons predominately express D1-DA receptors while striatopallidal neurons predominately express D2-DA receptors. Prior work suggests that METH-induced functional impairments are substantially more pronounced in striatonigral neurons (Daberkow et al. 2008, Chapman et al. 2001, Johnson-Davis et al. 2002), consistent with findings reported for rats with partial DA loss induced by 6-hydroxydopamine (Nisenbaum et al. 1996). Such changes may be due, in part, to impairments in phasic DA signaling associated with the METH-induced neurotoxicity (Howard et al. 2011), as the D1-DA receptor may be particularly sensitive to such changes (Dreyer et al. 2010, Floresco et al. 2003).

The immediate-early gene Arc/Arg3.1 (activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein) is a critical mediator of normal neuroplasticity processes and is induced by N-methyl-D-asparate (NMDA)-receptor activation before being trafficked to activated synapses where it is locally translated (Bramham et al. 2008, Lyford et al. 1995). Arc mRNA expression is induced in an experience-dependent manner (Guzowski et al. 1999, Daberkow et al. 2007) within GABAergic striatal neurons (Vazdarjanova et al. 2006). Arc protein itself is critical to modulating excitatory glutamatergic inputs via endocytosis of AMPA-type glutamate receptors (Chowdhury et al. 2006, Rial Verde et al. 2006) and to maintaining synaptic plasticity via modulation of long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) (Bramham et al. 2008, Bloomer et al. 2008). Blocking Arc translation via antisense oligonucleotide infusions impairs consolidation of learning (Guzowski et al. 2000), including basal ganglia-mediated learning (Hearing et al. 2011, Pastuzyn et al. 2012). Thus, Arc is critical for consolidation of learning, including those processes mediated by dorsal striatum.

We have previously reported that despite equivalent numbers of neurons showing transcriptional activation of the Arc gene, there are more striatonigral neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm than striatopallidal neurons in normal animals following exploration of a novel environment (Daberkow et al. 2007)—the prototypical behavioral paradigm used to assess Arc expression (Vazdarjanova et al. 2006, Guzowski et al. 1999, Chawla et al. 2005). Furthermore, we have previously reported that rats with prior exposure to a neurotoxic regimen of METH show decreased numbers of striatal neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression after engaging in a striatally-mediated, response-reversal learning task, with the greatest impairment being in the numbers of striatonigral neurons (Daberkow et al. 2008). Also, the correlation between Arc mRNA expression in dorsomedial (DM) striatum and trials to criterion on the response-reversal learning task observed in normal animals (Daberkow et al. 2008, Daberkow et al. 2007) is lost in METH-pretreated animals (Daberkow et al. 2008). Furthermore, reversal learning in METH-pretreated rats is no longer sensitive to antisense oligonucleotide-mediated disruption of Arc translation in DM striatum (Pastuzyn et al. 2012). However, the paradigms examined to date do not allow us to discern whether the decreased numbers of striatal neurons with Arc mRNA expression in the cytoplasm in METH-pretreated rats arises due to deficits in transcriptional activation of the Arc gene or deficits in the trafficking of Arc mRNA into the cytoplasm. Thus, the goal of the present studies was to determine whether METH-induced neurotoxicity is associated with acute disruption of Arc transcriptional activation vs. longer-duration processes regulating Arc trafficking/cytoplasmic stability. Furthermore, an additional goal of the present work was to examine further whether there are phenotypic differences in the acute regulation of Arc mRNA transcriptional activation and cytoplasmic expression following METH-induced neurotoxicity so as to better define how partial DA depletion impacts upon striatal efferent neuron function. Clarifying the impact of METH-induced neurotoxicity on the transcriptional activation and cytoplasmic regulation of Arc mRNA in striatum is critical so as to better inform treatment strategies to ameliorate cognitive and behavioral impairments in human METH abusers (Volkow et al. 2001, Kalechstein et al. 2003, Johanson et al. 2006).

Methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC; 275-300g) were singly housed in tub cages in a room controlled for temperature and lighting (12:12 hr). All animal care and experimental procedures conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th Ed.), followed the ARRIVE guidelines (Kilkenny et al. 2010) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Utah.

Methamphetamine treatment

Rats were treated with ( ± )-methamphetamine hydrochloride (NIDA, Research Triangle Park, NC) as previously described (Son et al. 2011, Daberkow et al. 2008). This specific regimen was chosen to model METH-induced damage to striatal monoamine systems. While METH self-administration models may more closely mimic human exposure by self-administration, such contingent models typically do not recapitulate long-lasting striatal DA toxicity (Brennan et al. 2010, Schwendt et al. 2009, McFadden et al. 2012, Reichel et al. 2012)), perhaps due to the duration of the exposure, as one study (Krasnova et al. 2010)), with much longer daily access (15 hr/day for 8 days) did report DA neuron toxicity. Thus, the single-day, non-contingent binge regimen implemented in the present study serves as a more rapid and reproducible model with face validity to the striatal DA depletions present in individuals with a history of METH exposure and who may, in fact, be in a preclinical Parkinsonian state. On the METH treatment day, rats were housed 5-6 animals per cage. Rats received four injections of either (±)-METH (10 mg/kg free base, s.c.) or 0.9% saline (1 mL/kg, s.c.) at 2-hr intervals, with rectal temperatures recorded hourly (Figure 1A). If core temperature exceeded 41°C, the rat was removed and placed in a separate cage over ice to decrease hyperthermia. Twelve hours after the final injection, rats were returned to home cages and given free access to food and water until behavioral manipulations three weeks later.

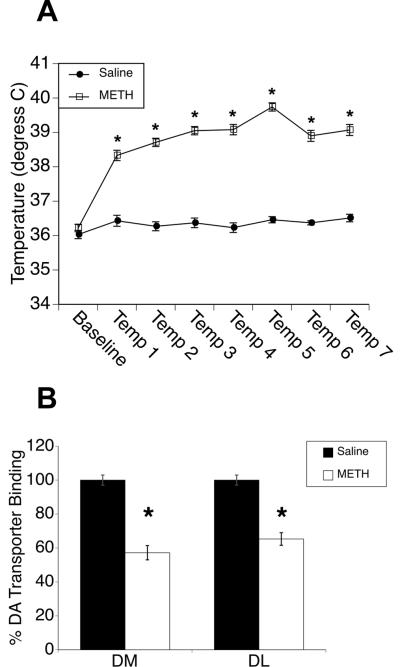

Figure 1. Methamphetamine pretreatment and subsequent DA depletions.

A) A neurotoxic regimen of methamphetamine (METH; 4 × 10 mg/kg) leads to a significant elevation of core body temperature relative to saline-treated animals (treatment effect F(1,54)=192.9, p<0.0001). B) METH-pretreated rats (n = 40) show significant DA depletions in both dorsomedial (DM) and dorsolateral (DL) striatum as measured by [125I]RTI-55 dopamine transporter autoradiography three weeks later (mean gray values (arbitrary units)±SEM expressed as % of saline control (n = 23)). * Significantly different from saline control, p≤0.05.

Behavioral activation via novel environment exploration

Rats were divided into three experimental groups (“5-min”, “30-min”, caged controls (CC)), each consisting of 6-8 saline- or 10-11 METH-pretreated rats. After initially observing elevated basal Arc expression in CC METH rats, an additional 7 rats were treated with METH as described above and sacrificed as CC. Thus, the METH CC group consisted of 18 animals. Rats were removed from their home cage after having been isolated for 24 hours. CC rats were sacrificed immediately upon removal from the home cage. Rats in the “5-min” group were exposed to a novel environment (50 × 40 × 40 cm tall Rubbermaid tub with pictures on two walls, as previously described (Daberkow et al. 2007, Guzowski et al. 1999)) for 5 min, then immediately sacrificed. Rats in the “30-min” group were exposed for 5 min to the novel environment, returned to the home cage for 25 min, and then sacrificed. Animals were sacrificed by CO2 exposure, decapitated, and brains immediately removed and flash-frozen in 2-methylbutane (Mallinckrodt Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ) chilled on dry ice.

Tissue preparation

Twelve-μm cryosections of striatum (Cambridge Instruments, Bayreuth, Germany; Bregma: +1.60 to −0.8 mm (Paxinos and Watson, 1998)) were thaw-mounted onto SuperFrost Plus slides (VWR, Batavia, IL), then postfixed as previously described (Ganguly & Keefe 2001).

DAT Autoradiography

METH-induced DA depletions in dorsal striatum were analyzed using [I125]RTI-55 binding to the dopamine transporter (DAT), as described previously (Boja et al. 1992, Pastuzyn et al. 2012). DAT binding levels were normalized to percent of saline controls for DM and dorsolateral (DL) striatum (Figure 1B).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization for Arc/ppe mRNAs

Expression of Arc mRNA in striatal efferent neurons was determined by double-label fluorescence in situ hybridization histochemistry (FISH) for Arc and ppe mRNAs, as previously described (Daberkow et al. 2008, Daberkow et al. 2007). Full-length ribonucleotide probes complementary to mRNAs for Arc (Lyford et al., 1995) and ppe (Yoshikawa et al., 1984) were synthesized from cDNAs using digoxigenin-UTP (DIG-UTP) and fluorescein-UTP (FITC-UTP) with T7 and SP6 RNA polymerases and DIG- and FITC-UTP RNA-labeling kits, respectively (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN).. Ribonucleotide probes were hybridized and detected as previously described (Daberkow et al. 2008, Daberkow et al. 2007).

Image acquisition

DAT film autoradiograms were digitized, and four sections per animal in rostral (+1.6 mm from bregma), middle (+0.5 mm from bregma) and caudal (−0.8 mm from bregma) dorsal striatum analyzed with ImageJ (Pastuzyn et al. 2012).

For FISH, a 0.18 mm2 montage from DM striatum was captured with an FV1000 confocal laser-scanning microscope (Olympus) with motorized stage (Prior Scientific) using a 60x, 1.45 NA oil-immersion lens (plan APO) and 488-nm Ar and 543-nm and 633-nm HeNe lasers. Areas of analysis were z-sectioned in 1-μm-thick optical sections (10 z-sections per image) (Daberkow et al. 2008, Daberkow et al. 2007). The numbers of ppe-pos and ppe-neg neurons with Arc mRNA staining in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm were determined, as previously described (Daberkow et al. 2007, Guzowski et al. 1999, Daberkow et al. 2008).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of DAT binding was accomplished by two-sample t-tests. METH and saline effects on body temperature were analyzed by MANOVA. Expression of Arc mRNA in each subcellular compartment was first compared across saline- and METH-pretreated rats using MANOVA (treatment × time × phenotype), although for clarity, Arc expression data are shown in separate, side-by-side graphs for saline- and METH-pretreated rats (Figs. 3, 4). Post-hoc analyses of significant interactions were achieved via Tukey-Kramer test for between-subjects factors (treatment, time) or post-hoc t-tests for the within-subjects factor (phenotype). For all analyses, p-values <0.05 were significant.

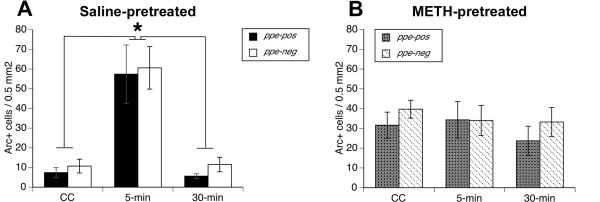

Figure 3. Nuclear Arc mRNA expression in striatal efferent neurons.

Data are mean (±SEM; saline n = 6-8; METH n = 10-18 per time point) numbers of labeled neurons per 0.5 mm2 determined from double fluorescent in situ hybridization staining for preproenkeaphalin and Arc (activity regulated, cytoskeleton-associated) mRNAs in the dorsomedial striata of rats treated approximately three weeks prior to sacrifice with A) saline (4×1 mL/kg) or B) a neurotoxic regimen of (±)-methamphetamine (METH; 4×10 mg/kg, s.c. at 2-hr intervals). Rats were either sacrificed immediately upon removal from the home cage (“caged control”; CC), allowed to explore a novel environment for 5 min and then sacrificed (5-min), or allowed to explore the novel environment for 5 min before being returned to the home cage for 25 min before being sacrificed (30-min). There is a significant main effect of METH-pretreatment relative to saline-pretreatment (p<0.02). * Significant main effect of time (5-min point significantly different from both the CC and 30-min groups).

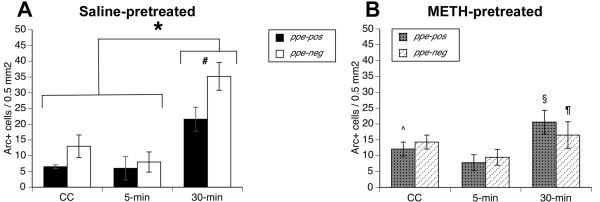

Figure 4. Cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression in striatal efferent neurons.

Data are mean (±SEM; saline n = 6-8; METH n =10-18 per time point) numbers of labeled neurons per 0.5 mm2 determined from double fluorescent in situ hybridization staining for preproenkeaphalin and Arc (activity regulated, cytoskeleton-associated) mRNAs in the dorsomedial striata of rats treated approximately three weeks prior to sacrifice with A) saline (4×1 mL/kg) or B) a neurotoxic regimen of (±)-methamphetamine (METH; 4×10 mg/kg, s.c. at 2-hr intervals). Rats were either sacrificed immediately upon removal from the home cage (“caged control”; CC), allowed to explore a novel environment for 5 min and then sacrificed (5-min), or allowed to explore the novel environment for 5 min before being returned to the home cage for 25 min before being sacrificed (30-min). * Significantly different from all other saline-pretreated groups, p≤0.05. # Significantly greater than number of ppe-pos neurons in same group. ^ Significantly greater than the number of ppe-pos neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm in the saline-pretreated, CC group. § Significantly greater than the number of ppe-pos with Arc mRNA expression in the cytoplasm in the METH-pretreated, CC group. ¶ Significantly less than the number of ppe-neg neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm in the saline-pretreated, 30-min group.

Results

METH-induced partial dopamine depletions

Treatment with METH resulted in hyperthermia necessary to produce long-term neurotoxicity (Ali et al. 1994). METH-treated rats reached maximum temperatures of 39.7°C (±0.8°C; Figure 1A), whereas saline-treated rats achieved maximum temperatures of 36.8°C (±0.5°C). There were significant main effects of treatment (F(1,54)=192.9, p<0.0001) and time (F(3,54)=102.1, p<0.0001) and a significant time × treatment interaction (F(3,54)=113.0, p<0.0001). At all time points after baseline, core temperatures in METH-treated rats were significantly elevated over saline (baseline, p=0.3; temp 1-temp 7, p<0.0001). Three-weeks later, DAT binding in DM striatum was 57.2±4.2% of control (mean±SEM; n=40 METH, n=23 saline; t(1,26)=−9.51, p<0.0001), and that in DL striatum was 65.5±3.7% of control (t(1,26)=−10.14, p<0.0001; Figure 1B).

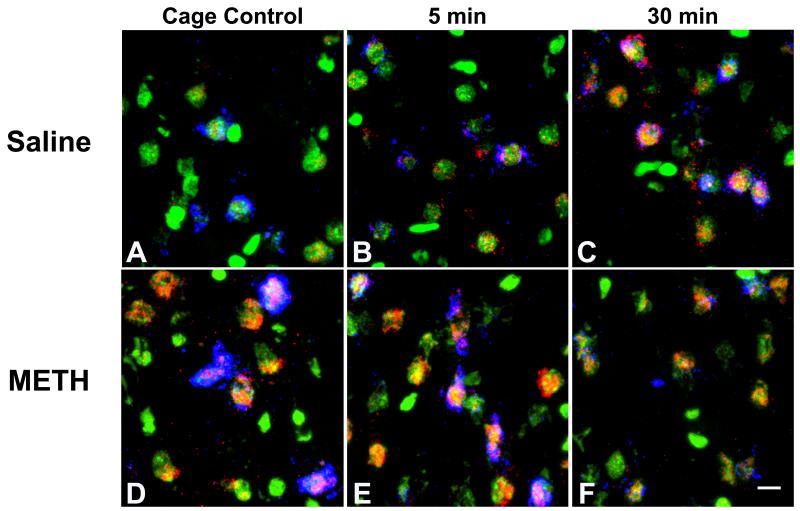

METH-induced neurotoxicity is associated with impaired transcriptional activation of Arc mRNA

Using catFISH (Guzowski et al. 1999, Daberkow et al. 2008, Daberkow et al. 2007), we determined the subcellular localization of Arc mRNA in striatal efferent neurons following spatial exploration of a novel environment (Figure 2A-F). As previously reported in normal animals (Daberkow et al. 2007, Guzowski et al. 1999), exposure to the novel environment increased nuclear Arc mRNA expression within 5 min (Figure 2 and 3A). MANOVA revealed significant main effects of time (F(2,54)=6.0, p<0.005) and treatment (F(1,54)=5.96, p<0.02) and a significant time × treatment interaction (F(2,54)=4.99, p<0.02). There was no main effect of phenotype (F(1,54)=2.72, p=0.1) and no phenotype × time (F(2,54)=0.7, p=0.5), phenotype × treatment (F(1,54)=0.5, p=0.5) or phenotype × time × treatment (F(2,54)=0.6, p=0.6) interactions. Post-hoc analysis of the time × treatment interaction revealed that in saline-pretreated rats the number of cells with nuclear Arc mRNA expression was significantly greater in the 5-min group than in the CC (p<0.01) or 30-min (p<0.001) groups. There were no such effects in METH-pretreated rats, as the numbers of cells with intranuclear foci of Arc mRNA in the METH-pretreated groups were not different from each other (p>0.1). However, overall (main effect of treatment) there were more cells with nuclear Arc mRNA in the METH-vs. saline-pretreated rats (p<0.02; Figure 3A vs. 3B). Thus, rats with METH-induced neurotoxicity have higher basal Arc transcription, but fail to induce Arc transcription in response to behavioral activation.

Figure 2. Representative photomicrographs of Arc mRNA expression in rat dorsomedial striatum.

Representative in situ hybridization histochemical images from rats pretreated with saline (4 × 1mL/kg; A-C) or a neurotoxic regimen of (±)-methamphetamine (METH; 4 × 10 mg/kg, s.c. at 2-hr intervals) and then either sacrificed immediately upon removal from the home cage (“caged control”; A, D), allowed to explore a novel environment for 5 min and then sacrificed (5-min; B, E), or allowed to explore the novel environment for 5 min before being returned to the home cage for 25 min before being sacrificed (30-min; C, F). Green is Sytox nuclear counter stain, blue is preproenkephalin mRNA and red is Arc (activity-regulated, cytoskeleton-associated) mRNA expression. Scale bar = 10 μm.

METH-induced neurotoxicity is associated with impaired cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression

As previously reported (Daberkow et al. 2007), saline-pretreated rats in the 30-min group had a significant increase in the number of striatal efferent neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm (Figure 4, 5). Furthermore, as we have previously reported (Daberkow et al., 2007, 2008), normal animals had more striatonigral (ppe-neg) than striatopallidal (ppe-pos) neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression (Fig. 4, 5A). Specifically, MANOVA revealed a significant main effect for time (F(2,54)=16.9, p<0.0001) and significant time × treatment (F(2,54)=3.3, p<0.05) and phenotype × time × treatment (F(2,54)=3.8, p<0.03) interactions. There was no significant main effect of treatment (F(1,54)=0.7, p=0.4) or phenotype (F(1,54)=3.1, p=0.08) and no significant phenotype × time (F(2,54)=0.6, p=0.5) or phenotype × treatment (F(1,54)= 0.8, p=0.4) interactions. Post-hoc analysis of the time × treatment interaction revealed greater numbers of neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression in saline-pretreated, 30-min rats relative to saline-pretreated, CC (p=0.002) and 5-min (p<0.001) groups, consistent with previous reports regarding the time course of normal Arc trafficking (Guzowski et al. 1999, Daberkow et al. 2007). Conversely, there were no significant differences between the numbers of cells with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression in the METH-pretreated, 30-min group relative to the METH-pretreated, CC (p=0.6) and 5-min (p=0.1) groups, again indicating a general overall lack of Arc mRNA induction associated with spatial exploration in METH-pretreated rats.

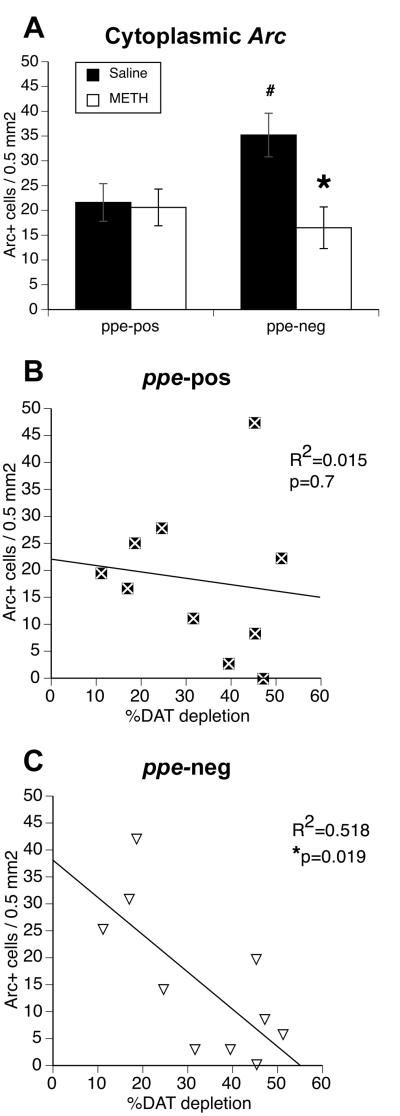

Figure 5. Cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression in striatal efferent neurons of rats sacrificed 30 min after exposure to a novel environment and relation to degree of methamphetamine-induced dopamine depletion.

Partial monoamine depletion significantly only affects the numbers of ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression. A) Mean (±SEM; saline n = 8; METH n =11) numbers of labeled neurons per 0.5 mm2 determined from double fluorescent in situ hybridization staining for preproenkeaphalin and Arc (activity regulated, cytoskeleton-associated) mRNAs in the dorsomedial striata of rats treated approximately three weeks prior to sacrifice with saline (4×1 mL/kg) or a neurotoxic regimen of (±)-methamphetamine (METH; 4×10 mg/kg, s.c. at 2-hr intervals). These data are the same “30-min” data presented in Figure 4, but are re-graphed to highlight the differences between the striatal efferent neuron subtypes at this time point. * Significantly different from number of ppe-neg neurons in saline-pretreated rats. # Significantly different from number of ppe-pos neurons in saline-pretreated rats. B) Correlation between the numbers of ppe-pos neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm and the percent DA loss, as assessed by [125I]RTI-55 autoradiography for dopamine transporter binding, induced by the neurotoxic regimen of METH (4 × 10 mg/kg, s.c. at 2-hr intervals) three weeks prior to sacrifice. C) Correlation between the numbers of ppe-neg neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm and the percent DA loss, as assessed by [125I]RTI-55 autoradiography for dopamine transporter binding, induced by the neurotoxic regimen of METH (4 × 10 mg/kg, s.c. at 2-hr intervals) three weeks prior to sacrifice. * Significant correlation, p=0.019.

To examine the phenotypic differences, post-hoc t-tests were performed on the numbers of ppe-neg and ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA in saline- and METH-pretreated rats. Paired t-tests confirmed (Daberkow et al., 2007) greater numbers of both ppe-neg (t=3.9, p=0.003) and ppe-pos (t=3.9, p=0.001) neurons with cytoplasmic Arc in the saline-pretreated, 30-min group relative to saline-pretreated, CC group (Figure 4A) and that there were more ppe-neg than ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression in the saline-pretreated, 30-min group (Figure 4A, 5A; t=2.5, p=0.02). In METH-pretreated, CC rats, there was no significant difference from saline-pretreated, CC rats in the numbers of ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA (Figure 4; t=-0.28, p>0.1). Additionally, in METH-pretreated rats there was no significant increase in numbers of ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc at 30-min (Figure 4B; t=0.44, p=0.31) relative to METH-pretreated, CC group, whereas there was a significant increase in the numbers of ppe-pos neurons (Figure 4B; t=2.2, p=0.02). Thus, in the METH-pretreated, 30-min group there was no longer a phenotypic difference between the numbers of ppe-neg and ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc (Figure 4B, 5A; t=-0.95, p=0.82), but there were significantly fewer ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression relative to the saline-pretreated, 30-min group (Figure 4B, 5A; t=3.0, p=0.004). Interestingly, there were more ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression in the METH-pretreated, CC group than in the saline-pretreated, CC group (Figure 4; t=-2.4, p=0.01), and also slightly more ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA in METH-pretreated, 30-min relative to METH-pretreated, CC rats (Figure 4B; t=1.9, p=0.04). However, there was no difference between the saline- and METH-pretreated 30-min groups in the numbers of ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression (Figure 4, 5A; t=0.18, p=0.43).

Upon observing impaired cytoplamsic Arc expression in ppe-neg neurons in the METH-pretreated, 30-min group, we assessed whether this impairment was uniformly distributed across METH-pretreated rats or whether this difference correlated to the DA depletion in each animal. Using only cell counts from the METH-pretreated, 30-min group, we correlated the numbers of striatal efferent neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm with the percent DA depletion as assessed by DAT autoradiography (Figure 5B, C). The numbers of ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA were not significantly correlated with DA loss (Figure 5B; R2=0.015, p=0.7). Conversely, the numbers of ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression was significantly inversely correlated to the DA depletion (Figure 5C; R2=0.518, p=0.019), indicating that greater DA loss is associated with fewer ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA expression. In the METH-pretreated, 5-min group, there was no significant correlation between cells with nuclear Arc and DA depletion (ppe-pos R2=0.005, p>0.5; ppe-neg R2=0.05, p>0.05).

Discussion

Herein, we report novel findings that basal Arc transcription in striatal efferent neurons is enhanced, but Arc mRNA transcriptional activation and cytoplasmic localization in response to behavioral activation is severely impaired, in rats with METH-induced neurotoxicity. Specifically, behavioral activation associated with spatial exploration of a novel environment – the classic paradigm used to examine Arc mRNA induction and trafficking (Guzowski et al. 1999, Daberkow et al. 2007, Vazdarjanova et al. 2006, Chawla et al. 2005) – resulted in no concomitant increase in cells with nuclear Arc expression above the elevated CC levels in METH-pretreated groups. There was also no significant overall increase in total number of neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA in the METH-pretreated, 30-min group, particularly with respect to ppe-neg neurons, similar to the suppressed cytoplasmic expression previously reported following a striatally-mediated response-reversal task (Daberkow et al. 2008). Interestingly, the degree of DA depletion was significantly negatively correlated with the numbers of ppe-neg cells with cytoplasmic Arc, suggesting that the loss of this expression may arise as a consequence of disrupted DA signaling in striatum. Taken together, these data reveal a profound dysregulation of Arc transcriptional activation and subcellular trafficking. As Arc mRNA, and the resulting Arc protein, is critical to normal neuroplasticity processes (Chowdhury et al. 2006), such disruption may contribute to disrupted Arc-mediated memory processes of the basal ganglia subsequent to METH pretreatment (Daberkow et al. 2008, Pastuzyn et al. 2012).

We presently demonstrate an intriguing increase in basal (CC) Arc mRNA transcription following METH-induced neurotoxicty relative to saline-pretreated controls. Persistent changes in basal gene expression are not uncommon after repeated exposure to psychostimulants (c.f. (Unal et al. 2009), including reports from our lab showing long-term decreases in preprotachykinin mRNA expression after METH-induced neurotoxicity (Chapman et al. 2001, Johnson-Davis et al. 2002). However, to our knowledge, there are no prior reports of long-term changes in basal immediate early gene expression in striatal neurons as a consequence of METH-induced neurotoxicity. Given that prior work suggested a relatively preferential impact of METH-induced neurotoxicity on striatonigral neuron function (Johnson-Davis et al. 2002, Chapman et al. 2001, Daberkow et al. 2008), the equivalent increases in basal Arc transcription observed in ppe-pos and ppe-neg neurons were surprising and suggest global alterations in striatal efferent neuron function following METH-induced neurotoxicity. This up-regulation may reflect alterations in signals regulating Arc transcription, including brain-derived neurotrophic factor or glutamate. While both of these molecules are elevated 24-72 hrs after exposure of animals to a neurotoxic regimen of METH (Mark et al. 2007, Thomas et al. 2004), whether they remain elevated in striatum weeks later is unknown. Clearly, further studies are needed to examine the mechanisms underlying long-term dysregulation of basal Arc transcription and also the extent to which the expression of other plasticity-related genes is similarly altered.

The present studies also reveal a profound impairment of acute, novelty-induced transcription of Arc in rats with METH-induced neurotoxicity. The basis for this observation is presently unknown, but changes in phasic DA release seem a likely contributing factor. Partial monoamine loss is associated with impaired phasic-like, but not tonic-like, DA release (Bergstrom & Garris 2003, Howard et al. 2011). Modeling data suggest that D1-DA receptors should be particularly sensitive to changes in phasic DA amplitude (Dreyer et al. 2010). Consistent with this model, phasic-like stimulation of DA transmission increases gene expression in and electrophysiological activity of striatonigral, but not striatopallidal, neurons (Gonon 1997, Onn et al. 2000, Chergui et al. 1997). Finally, we presently report that in METH-pretreated rats, the impairment in numbers of ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA correlates with the extent of DA loss, which is further known to correlate with the degree of impairment of phasic-like DA neurotransmission (Bergstrom & Garris 2003, Howard et al. 2011). Thus, impaired phasic DA neurotransmission may ultimately contribute to the observed deficits in Arc expression subsequent to METH-induced neurotoxicity.

Decreased phasic DA neurotransmission and consequent decreases in D1-DA receptor activation may also impair Arc transcription by altering upstream signaling cascades. Activation of D1-DA receptors enhances NMDA receptor-mediated currents in striatonigral neurons (Jocoy et al. 2011, Cepeda et al. 1993, Andre et al. 2010) and increases activation of ERK1/2 (Valjent et al. 2005, Pascoli et al. 2011). Arc transcription is regulated by NMDA receptor and ERK1/2 activation (Korb & Finkbeiner 2011). Thus, decreased D1-DA receptor activation due to attenuated phasic DA transmission likely results in decreased NMDA receptor and ERK1/2 activation and, thus, decreased activity-dependent Arc induction in ppe-neg neurons.

While the above-delineated effects can explain the basis for the impairment of acute, novelty-induced Arc transcription in ppe-neg neurons, the basis for the impaired transcriptional activation in ppe-pos neurons is less apparent. One possibility is that it also arises as a consequence of impaired phasic DA signaling and decreased D1-DA receptor activation in striatum. Disruption of striatal D1-DA receptor activation decreases cortical excitability (Yano et al. 2006, Gross & Marshall 2009, Steiner & Kitai 2000). Additionally, cortical immediate early gene induction by DA receptor agonists is blunted in rats with METH-induced neurotoxicity (Belcher et al. 2009). Furthermore, novelty-induced c-fos mRNA expression in striatopallidal neurons is dependent on corticostriatal transmission (Ferguson & Robinson 2004), sensitive to decreases in D1-DA receptor activation (Ferguson et al. 2003), and sensitive to blockade of NMDA receptors or ERK1/2 signaling (Ferguson et al. 2003, Ferguson & Robinson 2004). These data thus suggest a model wherein loss of D1-DA receptor activation in striatum due to disrupted phasic signaling secondary to METH-induced monoamine toxicity may lead to decreased cortical excitability and, consequently, decreased gene expression in ppe-pos neurons.

An alternative explanation for the overall loss of novelty-induced Arc transcription is that chronic elevations in basal Arc mRNA expression suppress further transcriptional activation. Massed exposures to a spatial environment in a single day impair Arc transcription (Guzowski et al. 2006) and AMPA receptor activation can inhibit Arc transcription (Rao et al. 2006). While there are DNA regulatory elements that repress Arc transcription (Pintchovski et al. 2009), what binds to those regulatory sites and the situations under which they are engaged are currently undefined. Therefore, the extent to which transcriptional repression of the Arc gene vs. impaired activation of postsynaptic receptors (NMDA, D1) or intracellular signaling cascades contributes to the loss of evoked Arc expression in rats with METH-induced neurotoxicity remains to be determined.

The present results confirm prior observations (Daberkow et al. 2008, Daberkow et al. 2007) that normal, saline-pretreated animals have more ppe-neg neurons than ppe-pos neurons with Arc mRNA in the cytoplasm. At present, the basis for this phenotypic difference in normal animals is unknown, but it may be related to differences in Arc trafficking or cytoplasmic mRNA stability, given that Arc mRNA is a substrate for translation-dependent decay (Giorgi et al. 2007). The lack of transcriptional activation of Arc in rats with METH-induced neurotoxicity makes it somewhat difficult to discern whether DA contributes to this phenotypic difference; however, the present results suggest that the trafficking/stability of Arc mRNA in ppe-neg neurons in normal animals is dependent on DA signaling. First, despite the lack of novelty-induced transcriptional activation, METH-pretreated, CC rats have more ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc than do saline-pretreated, CC rats, suggesting that METH-pretreated rats still traffic basally transcribed Arc mRNA into the cytoplasm in ppe-pos neurons. Conversely, despite having high basal numbers of ppe-neg neurons with transcriptional activation of Arc, METH-pretreated, 30-min rats do not have greater numbers of ppe-neg neurons with cytoplasmic Arc expression compared to saline-pretreated, 30-min rats. Thus, the elevated basal transcription of Arc mRNA in ppe-neg neurons of METH-pretreated rats does not translate into greater numbers of neurons with cytoplasmic Arc, suggesting some disruption of Arc trafficking/stability in ppe- neg neurons. Second, whereas there is a slight, but significant, increase in the numbers of ppe-pos neurons with cytoplasmic Arc mRNA in the METH-pretreated, 30-min group relative to the numbers in the METH-pretreated, CC group, there is no such increase in the numbers of ppe-neg neurons. Taken together, these observations suggest that METH-induced neurotoxicity is associated with impaired acute transcriptional activation of Arc in both subtypes of striatal efferent neurons, as well as impaired trafficking/stability specifically in ppe-neg neurons.

We presently report that a neurotoxic regimen of METH has significant, long-term impact on the regulation of transcriptional activation and subcellular expression of Arc mRNA. This METH-induced effect on Arc mRNA transcription and expression may thus impair Arc protein translation, with Arc protein synthesized within 60 min of neuronal stimulation (Baez et al. 2011, Vazdarjanova et al. 2006, Lyford et al. 1995). Importantly, this disrupted activity-dependent striatal Arc expression, and hypothesized impact on protein synthesis, may underlie previously reported changes in basal ganglia-mediated learning and memory processes in METH-pretreated rats, including response-reversal (Daberkow et al. 2008, Pastuzyn et al. 2012), sequential motor (Chapman et al. 2001), and stimulus-response vs. action-outcome (Son et al. 2011) learning. Our present results therefore suggest Arc mRNA or the factors regulating it as potential novel therapeutic targets in the treatment of METH-induced cognitive impairments (Kalechstein et al. 2003, Volkow et al. 2001, Johanson et al. 2006), as Arc is a critical mediator underlying normal neuroplasticity processes (Chowdhury et al. 2006, Rial Verde et al. 2006). Future work will thus need to examine whether therapeutically restoring partial DA loss will resolve the molecular and cellular changes that occur, as well as improve cognitive functionality compromised with METH addiction and abuse.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIDA DA024036 (KAK), the American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education (MBH) and the GPEN Program (KO).

Abbreviations

- Arc/Arg3.1

activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein

- METH

(±)-methamphetamine hydrochloride

- DA

dopamine

- ppe

preproenkephalin

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- LTD

long-term depression

- CC

cage control rats

- DIG-UTP

digoxigenin-UTP

- FITC-UTP

fluorescein-UTP

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DM

dorsomedial

- DL

dorsolateral

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ali SF, Newport GD, Holson RR, Slikker W, Jr., Bowyer JF. Low environmental temperatures or pharmacologic agents that produce hypothermia decrease methamphetamine neurotoxicity in mice. Brain Res. 1994;658:33–38. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(09)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre VM, Cepeda C, Cummings DM, Jocoy EL, Fisher YE, William Yang X, Levine MS. Dopamine modulation of excitatory currents in the striatum is dictated by the expression of D1 or D2 receptors and modified by endocannabinoids. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:14–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baez MV, Luchelli L, Maschi D, Habif M, Pascual M, Thomas MG, Boccaccio GL. Smaug1 mRNA-silencing foci respond to NMDA and modulate synapse formation. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:1141–1157. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher AM, O’Dell SJ, Marshall JF. Long-term changes in dopamine-stimulated gene expression after single-day methamphetamine exposure. Synapse. 2009;63:403–412. doi: 10.1002/syn.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom BP, Garris PA. “Passive stabilization” of striatal extracellular dopamine across the lesion spectrum encompassing the presymptomatic phase of Parkinson’s disease: a voltammetric study in the 6-OHDA-lesioned rat. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1224–1236. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomer WA, VanDongen HM, VanDongen AM. Arc/Arg3.1 translation is controlled by convergent N-methyl-D-aspartate and Gs-coupled receptor signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:582–592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boja JW, Mitchell WM, Patel A, Kopajtic TA, Carroll FI, Lewin AH, Abraham P, Kuhar MJ. High-affinity binding of [125I]RTI-55 to dopamine and serotonin transporters in rat brain. Synapse. 1992;12:27–36. doi: 10.1002/syn.890120104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramham CR, Worley PF, Moore MJ, Guzowski JF. The immediate early gene arc/arg3.1: regulation, mechanisms, and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11760–11767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3864-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Colussi-Mas J, Carati C, Lea RA, Fitzmaurice PS, Schenk S. Methamphetamine self-administration and the effect of contingency on monoamine and metabolite tissue levels in the rat. Brain Res. 2010;1317:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan RC, Cunningham JK, Sykes J, Kish SJ. Increased risk of Parkinson’s disease in individuals hospitalized with conditions related to the use of methamphetamine or other amphetamine-type drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepeda C, Buchwald NA, Levine MS. Neuromodulatory actions of dopamine in the neostriatum are dependent upon the excitatory amino acid receptor subtypes activated. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:9576–9580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman DE, Hanson GR, Kesner RP, Keefe KA. Long-term changes in basal ganglia function after a neurotoxic regimen of methamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla MK, Guzowski JF, Ramirez-Amaya V, Lipa P, Hoffman KL, Marriott LK, Worley PF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA. Sparse, environmentally selective expression of Arc RNA in the upper blade of the rodent fascia dentata by brief spatial experience. Hippocampus. 2005;15:579–586. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chergui K, Svenningsson P, Nomikos GG, Gonon F, Fredholm BB, Svennson TH. Increased expression of NGFI-A mRNA in the rat striatum following burst stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:2370–2382. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Shepherd JD, Okuno H, Lyford G, Petralia RS, Plath N, Kuhl D, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Arc/Arg3.1 interacts with the endocytic machinery to regulate AMPA receptor trafficking. Neuron. 2006;52:445–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daberkow DP, Riedy MD, Kesner RP, Keefe KA. Arc mRNA induction in striatal efferent neurons associated with response learning. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:228–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daberkow DP, Riedy MD, Kesner RP, Keefe KA. Effect of methamphetamine neurotoxicity on learning-induced Arc mRNA expression in identified striatal efferent neurons. Neurotox Res. 2008;14:307–315. doi: 10.1007/BF03033855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer JK, Herrik KF, Berg RW, Hounsgaard JD. Influence of phasic and tonic dopamine release on receptor activation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14273–14283. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1894-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SA, Gough BJ, Cada AM. In vivo basal and amphetamine-induced striatal dopamine and metabolite levels are similar in the spontaneously hypertensive, Wistar-Kyoto and Sprague-Dawley male rats. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Robinson TE. Amphetamine-evoked gene expression in striatopallidal neurons: regulation by corticostriatal afferents and the ERK/MAPK signaling cascade. J Neurochem. 2004;91:337–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, West AR, Ash B, Moore H, Grace AA. Afferent modulation of dopamine neuron firing differentially regulates tonic and phasic dopamine transmission. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:968–973. doi: 10.1038/nn1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly A, Keefe KA. Unilateral dopamine depletion increases expression of the 2A subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor in enkephalin-positive and enkephalin-negative neurons. Neuroscience. 2001;103:405–412. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Young WS., 3rd Distribution of striatonigral and striatopallidal peptidergic neurons in both patch and matrix compartments: an in situ hybridization histochemistry and fluorescent retrograde tracing study. Brain Res. 1988;460:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi C, Yeo GW, Stone ME, Katz DB, Burge C, Turrigiano G, Moore MJ. The EJC factor eIF4AIII modulates synaptic strength and neuronal protein expression. Cell. 2007;130:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonon F. Prolonged and extrasynaptic excitatory action of dopamine mediated by D1 receptors in the rat striatum in vivo. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5972–5978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05972.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Hellgren J, Menard A, Saitoh K, Wikstrom MA. Mechanisms for selection of basic motor programs--roles for the striatum and pallidum. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:364–370. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross NB, Marshall JF. Striatal dopamine and glutamate receptors modulate methamphetamine-induced cortical Fos expression. Neuroscience. 2009;161:1114–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Lyford GL, Stevenson GD, Houston FP, McGaugh JL, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Inhibition of activity-dependent arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3993–4001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-03993.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, McNaughton BL, Barnes CA, Worley PF. Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1120–1124. doi: 10.1038/16046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzowski JF, Miyashita T, Chawla MK, et al. Recent behavioral history modifies coupling between cell activity and Arc gene transcription in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1077–1082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505519103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearing MC, Schwendt M, McGinty JF. Suppression of activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated gene expression in the dorsal striatum attenuates extinction of cocaine-seeking. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;14:784–795. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710001173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard CD, Keefe KA, Garris PA, Daberkow DP. Methamphetamine neurotoxicity decreases phasic, but not tonic, dopaminergic signaling in the rat striatum. J Neurochem. 2011;118:668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jocoy EL, Andre VM, Cummings DM, Rao SP, Wu N, Ramsey AJ, Caron MG, Cepeda C, Levine MS. Dissecting the contribution of individual receptor subunits to the enhancement of N-methyl-d-aspartate currents by dopamine D1 receptor activation in striatum. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:28. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Frey KA, Lundahl LH, et al. Cognitive function and nigrostriatal markers in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;185:327–338. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Davis KL, Hanson GR, Keefe KA. Long-term post-synaptic consequences of methamphetamine on preprotachykinin mRNA expression. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1472–1479. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalechstein AD, Newton TF, Green M. Methamphetamine dependence is associated with neurocognitive impairment in the initial phases of abstinence. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15:215–220. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb E, Finkbeiner S. Arc in synaptic plasticity: from gene to behavior. Trends Neurosci. 2011;34:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova IN, Justinova Z, Ladenheim B, Jayanthi S, McCoy MT, Barnes C, Warner JE, Goldberg SR, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine self-administration is associated with persistent biochemical alterations in striatal and cortical dopaminergic terminals in the rat. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyford GL, Yamagata K, Kaufmann WE, et al. Arc, a growth factor and activity-regulated gene, encodes a novel cytoskeleton-associated protein that is enriched in neuronal dendrites. Neuron. 1995;14:433–445. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90299-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark KA, Quinton MS, Russek SJ, Yamamoto BK. Dynamic changes in vesicular glutamate transporter 1 function and expression related to methamphetamine-induced glutamate release. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6823–6831. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0013-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden LM, Hadlock GC, Allen SC, et al. Methamphetamine self-administration causes persistent striatal dopaminergic alterations and mitigates the deficits caused by a subsequent methamphetamine exposure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:295–303. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.188433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisenbaum LK, Crowley WR, Kitai ST. Partial striatal dopamine depletion differentially affects striatal substance P and enkephalin messenger RNA expression. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;37:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00317-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Rodriguez MC, DeLong MR. Basal ganglia pathophysiology. A critical review. Adv Neurol. 1997;74:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onn SP, West AR, Grace AA. Dopamine-mediated regulation of striatal neuronal and network interactions. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:S48–56. doi: 10.1016/s1471-1931(00)00020-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoli V, Besnard A, Herve D, Pages C, Heck N, Girault JA, Caboche J, Vanhoutte P. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate-independent tyrosine phosphorylation of NR2B mediates cocaine-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastuzyn ED, Chapman DE, Wilcox KS, Keefe KA. Altered learning and arc-regulated consolidation of learning in striatum by methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:885–895. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintchovski SA, Peebles CL, Kim HJ, Verdin E, Finkbeiner S. The serum response factor and a putative novel transcription factor regulate expression of the immediate-early gene Arc/Arg3.1 in neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1525–1537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5575-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao VR, Pintchovski SA, Chin J, Peebles CL, Mitra S, Finkbeiner S. AMPA receptors regulate transcription of the plasticity-related immediate-early gene Arc. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:887–895. doi: 10.1038/nn1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichel CM, Chan CH, Ghee SM, See RE. Sex differences in escalation of methamphetamine self-administration: cognitive and motivational consequences in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2727-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rial Verde EM, Lee-Osbourne J, Worley PF, Malinow R, Cline HT. Increased expression of the immediate-early gene arc/arg3.1 reduces AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Neuron. 2006;52:461–474. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendt M, Rocha A, See RE, Pacchioni AM, McGinty JF, Kalivas PW. Extended methamphetamine self-administration in rats results in a selective reduction of dopamine transporter levels in the prefrontal cortex and dorsal striatum not accompanied by marked monoaminergic depletion. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:555–562. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son JH, Latimer C, Keefe KA. Impaired formation of stimulus-response, but not action-outcome, associations in rats with methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2441–2451. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner H, Kitai ST. Regulation of rat cortex function by D1 dopamine receptors in the striatum. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5449–5460. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05449.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Francescutti-Verbeem DM, Liu X, Kuhn DM. Identification of differentially regulated transcripts in mouse striatum following methamphetamine treatment--an oligonucleotide microarray approach. J Neurochem. 2004;88:380–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unal CT, Beverley JA, Willuhn I, Steiner H. Long-lasting dysregulation of gene expression in corticostriatal circuits after repeated cocaine treatment in adult rats: effects on zif 268 and homer 1a. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:1615–1626. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06691.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Pascoli V, Svenningsson P, et al. Regulation of a protein phosphatase cascade allows convergent dopamine and glutamate signals to activate ERK in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:491–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408305102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazdarjanova A, Ramirez-Amaya V, Insel N, et al. Spatial exploration induces ARC, a plasticity-related immediate-early gene, only in calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-positive principal excitatory and inhibitory neurons of the rat forebrain. J Comp Neurol. 2006;498:317–329. doi: 10.1002/cne.21003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, et al. Association of dopamine transporter reduction with psychomotor impairment in methamphetamine abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:377–382. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GC, Ricaurte GA, Seiden LS, Schuster CR, Miller RJ, Westley J. Long-lasting depletions of striatal dopamine and loss of dopamine uptake sites following repeated administration of methamphetamine. Brain Res. 1980;181:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann T, DeLong MR. Functional and pathophysiological models of the basal ganglia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:751–758. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolverton WL, Ricaurte GA, Forno LS, Seiden LS. Long-term effects of chronic methamphetamine administration in rhesus monkeys. Brain Res. 1989;486:73–78. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Beverley JA, Steiner H. Inhibition of methylphenidate-induced gene expression in the striatum by local blockade of D1 dopamine receptors: interhemispheric effects. Neuroscience. 2006;140:699–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]