Abstract

The microtubule (MT)-associated protein tau, which is highly expressed in the axons of neurons, is an endogenous MT-stabilizing agent that plays an important role in the axonal transport. Loss of MT-stabilizing tau function, caused by misfolding, hyperphosphorylation and sequestration of tau into insoluble aggregates, leads to axonal transport deficits with neuropathological consequences. Several in vitro and preclinical in vivo studies have shown that MT-stabilizing drugs can be utilized to compensate for the loss of tau function and to maintain/restore an effective axonal transport. These findings indicate that MT-stabilizing compounds hold considerable promise for the treatment of Alzheimer disease and related tauopathies. The present article provides a synopsis of the key findings demonstrating the therapeutic potential of MT-stabilizing drugs in the context of neurodegenerative tauopathies, as well as an overview of the different classes of MT-stabilizing compounds.

Microtubule (MT) dynamics, axonal transport and neurodegenerative tauopathies

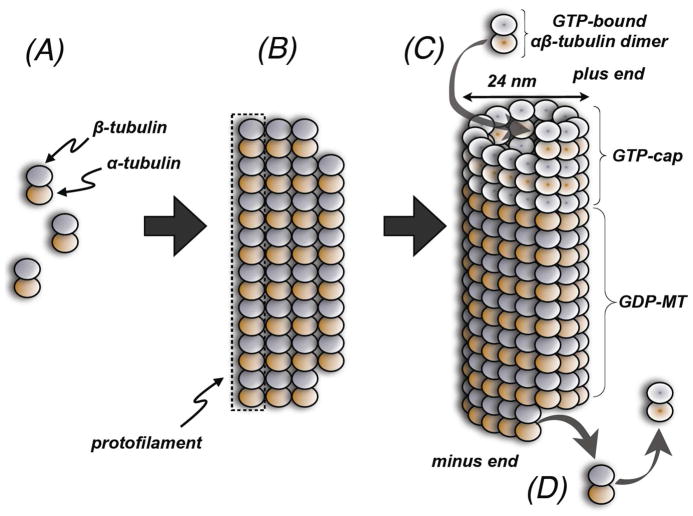

Microtubules (MTs), essential constituents of the cytoskeleton in eukaryotic cells, are involved in a number of important structural and regulatory functions, including the maintenance of cell shape, intracellular transport machinery, as well as cell-growth and division. Structurally, MTs are hollow tubes of approximately 24 nm in diameter that result from the head-to-tail polymerization of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers (Figure 1).1

Figure 1.

Schematic of the tubulin polymerization process. (A) head-to-tail polymerization of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers results in the formation of protofilaments; (B) lateral interactions between protofilaments enable them to assemble into sheets of tubulin, which fold on themselves to form hollow MT structures typically comprising 13 protofilaments per MT. (C) During MT-polymerization, guanosine-5′-triphosphate (GTP)-bound α,β-tubulin heterodimers are added at the polymerizing end of the MT. Concomitantly, or soon after incorporation into the MT, GTP-bound to β-tubulin is hydrolyzed to the corresponding diphosphate (GDP-MT). The GTP to GDP hydrolysis is not required for MT-polymerization, however, this conversion plays an important role in determining the dynamic instability of the MT, as GTP-tubulin forms more stable interactions, while GDP-tubulin establishes comparatively weaker intersubunit interactions and is, therefore, prone to depolymerization. The presence of a GTP-bound tubulin at the growing end of the MT (GTP-cap) protects the MT from depolymerization. Removal of the GTP-cap can trigger rapid depolymerization events. (D) Upon depolymerization, released tubulin heterodimers can exchange GDP with GTP and re-enter the polymerization cycle.

MTs are highly dynamic structures that alternate between growing and shrinking phases.2 Because of this dynamic nature, MTs can undergo relatively rapid turnover and form a variety of different arrays within cells. The presence of various tubulin isoforms, post-translational modifications, and interactions with MT-associated proteins (MAPs) play an important role in determining the morphology, stability, and, ultimately, the particular function of the MT lattice in different cell types.

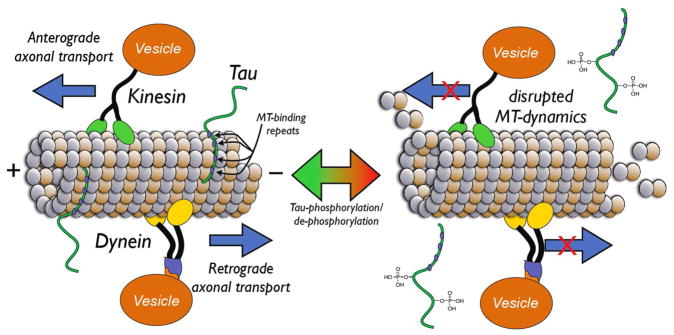

In the axons of neurons, MTs form polarized linear arrays with the plus ends directed toward the synapses and the minus ends toward the cell body. Such an organization of axonal MTs provides both structural support and directionality for the intracellular transport of proteins and vesicles to and from the cell-body and the synapses (Figure 2). This cytoskeletal structure, together with molecular motors such as kinesins and dyneins, form the axonal transport machinery, which is critical to the viability of neurons3 and notably, axonal transport defects are observed in several neurodegenerative diseases.4 In the case of tauopathies, which are a group of neurodegenerative diseases that include Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related forms of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), axonal transport deficits are thought to arise at least in part from the misfolding and aggregation of the MT-associated protein (MAP) tau.5 These tau aggregates form intracellular filamentous inclusions, known as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and neuropil threads, which, together with the senile plaques comprised of amyloid β (Aβ peptides, constitute the characteristic lesions that are diagnostic of AD. Furthermore, the presence of tau aggregates in the absence of deposits of Aβ peptides or other proteinaceous inclusions comprise the defining lesions of other tauopathies, such as Pick’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal degeneration, which are the most common forms of FTLD.5

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the axonal transport machinery, which comprises MTs, motor proteins (kinesins and dyneins) and cargos. Kinesins and dyneins move towards the plus and the minus end of the MTs, respectively, and are involved in either the anterograde (kinesins) or retrograde (dyneins) axonal transport. The MT-stabilizing function of tau plays an important role in the organization and dynamics of axonal MTs and, as such, is critical for axonal transport. Under pathological conditions, hyperphosphorylation of tau leads to an abnormal disengagement of tau from the MTs, which results in disruption of MT-dynamics and impaired axonal transport.

Tau is expressed particularly in the axons of neurons with the primary function to promote MT-stabilization.6 Under physiological conditions, the vast majority of tau molecules are bound to MTs. However, in neurons affected by tauopathies, tau becomes progressively disengaged from the axonal MTs, possibly due to hyperphosphorylation, which is known to reduce the binding affinity of this protein for the MTs.7, 8 An abnormal detachment of tau from the MTs is thought to alter the dynamics and organization of the axonal MTs, which in turn can trigger or exacerbate axonal transport defects.3 Furthermore, once detached from MTs and hyperphosphorylated, tau becomes considerably more prone to misfolding and aggregation.9, 10 This misfolded and/or aggregated tau can in turn recruit additional functional tau proteins into the aggregation cascade, contributing further to the destabilization of axonal MTs.11 Thus, based on the relationship between tau pathology and the appearance of MT12 and axonal transport deficits, a possible strategy for the treatment of AD and related tauopathies is to employ exogenous MT-stabilizing agents that could compensate for loss of tau maintenance of the appropriate organization and dynamics of the axonal MTs.13 Such an approach would hold the promise of restoring effective axonal transport in neurons affected by tauopathy and, as a result, prevent synaptic dysfunctions and neuron loss.13, 14

Over the past several decades, several classes of MT-stabilizing natural products have been discovered (Table 1) with the majority of these having been extensively characterized as cancer therapeutics due to the essential role of MTs in cell division. In contrast, as shown in Table 1, a comprehensive evaluation of the different classes of natural products in the context of neurodegenerative tauopathies has not as yet been achieved. A critical challenge facing the development of CNS-directed MT-stabilizing therapies to treat tauopathies is identifying brain-penetrant compounds that would be effective at non-toxic doses. Indeed, the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is equipped with relatively impermeable intercellular tight junctions, as well as with active transporters such as the P-glycoprotein (Pgp),15 is known to be a remarkable obstacle in the development of any CNS-directed therapy.16 It is estimated that <2% of all potential drug candidates can permeate across the BBB.17 In addition, MT-stabilizing drugs, which are routinely used in cancer chemotherapy, are known to cause a number of debilitating side-effects, which are directly linked to the MT-stabilizing properties of these compounds, and include neutropenia18 and peripheral neuropathy.19 Thus, even if brainpenetration issues were solved, long-term treatment of tauopathy patients with this class of therapeutics might be difficult due to dose-limiting toxicities. Despite these important challenges, different lines of research have validated the potential utility of MT-stabilization as a therapeutic approach to treat tauopathies. In vitro, MT-stabilizing agents have been found to protect cultured neurons against tau-20, 21 and Aβ-mediated22–24 neurotoxicity. In vivo, the first demonstration of the therapeutic potential of this type of compounds was reported in 2005,25 when paclitaxel treatment was found to restore fast axonal transport (FAT) and increase MT density in L5 axons that project from spinal motor neurons to lower limb muscles of T44 tau transgenic (Tg) mice affected by spinal cord tau pathology. Importantly, paclitaxel treatment produced an improvement in the motor weakness phenotype of these Tg mice due to uptake at neuromuscular junctions and retrograde transport.25 However, paclitaxel does not cross the BBB and is thus unsuitable as a therapeutic candidate for human tauopathies where tau pathology is primarily in the brain. More recently, a series of studies from our laboratories26, 27 and subsequently from Bristol Myers Squibb28 (BMS) provided further validation of this therapeutic approach using the brain-penetrant MT-stabilizing agent, epothilone D, to prevent and ameliorate disease in other lines of Tg mouse models with tau pathology in the brain that resembles that observed in tauopathy patients. In our studies, administration of low weekly doses of epothilone D by intraperitoneal (IP) injections into PS19 mice, which have NFT-like inclusions in the brain,29 produced normalization of MT density, restoration of FAT, reduction in axonal dystrophy and decrease in neuronal pathology and death, with consequent improvement in cognitive performance.26, 27 Notably, these effects were seen both in preventative and interventional studies in which epothilone D was administered to PS19 mice either before or after the onset of tau pathology. Similar outcomes on neuropathology and cognition were observed in the BMS studies in which epothilone D was administered to rTg4510 and 3X tau Tg mice.28

Table 1.

Different classes of MT-stabilizing natural products and their stage of development as potential candidates for neurodegenerative tauopathies.

| Compound class | Brain penetration | Stage of development in the context of tauopathies |

|---|---|---|

| Taxanes | Paclitaxel, docetaxel and several related analogues are not brain penetrant; selected analogues and/or prodrugs are reported to exhibit improved brain penetration.32–35 | Paclitaxel was evaluated in an animal model of tauopathies.25 Lack of brain penetration prevented further development of this compound. |

| Epothilones | Several examples reported to be brain penetrant.36–38 | Epothilone D was evaluated in animal models26, 27 and recently entered Phase Ib clinical trial for AD.28 |

| Discodermolide | Not reported | Not reported |

| Dictyostatin | Not reported | Not reported |

| Eleuthesides | Not reported | Not reported |

| Laulimalide | Not reported | Not reported |

| Peloruside | Not reported | Cell-based studies.21 |

| Cyclostreptin | Not reported | Not reported |

| Taccalonolides | Not reported | Not reported |

| Zampanolide | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ceratamines | Not reported | Not reported |

One important observation that was made in both the paclitaxel25 and epothilone D in vivo studies 26, 28 is that the dose-response curves appeared to be U-shaped, with relatively low doses of the compounds (e.g., 100 times below the cumulative cancer chemotherapeutic dose, in the case of epothilone D26–28) being most efficacious. This result indicates that low doses of MT-stabilizing agents may be both necessary and sufficient to restore the dynamics of axonal MTs and normalize FAT to physiological levels, and thus produce optimal therapeutic effects. Over-stabilization of MTs on the other hand may in fact be counter-productive and could be accompanied by side-effects such as peripheral neuropathy. Thus, an important outcome of the sustained low dose treatments with MT-stabilizing drugs is that Tg animals did not show signs of toxicities,26–28 including peripheral neuropathy and neutropenia.

Collectively, these findings indicate that brain-penetrant MT-stabilizing agents may be useful for the treatment of AD and related FTLD tauopathies. Pleasingly, BMS has recently initiated a Phase Ib clinical trial in which epothilone D is being evaluated in AD patients.30 Moreover, since ~80% of Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients develop dementia (PDD) by ~10 years after onset of PD, and AD-like tau pathology is associated with cognitive impairment in PDD, MT-stabilizing agents could be of therapeutic benefit to PDD patients.31

The highly promising results obtained from the epothilone D studies in our tau Tg animal models raise the possibility that other MT-stabilizing agents may be identified as alternative and potentially improved clinical candidates. As summarized in Table 1, although a growing number of MT-stabilizing natural products continue to be discovered, to date, only few selected compounds have been characterized as potential candidates for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. In the sections below, we provide an overview of the different classes of MT-stabilizing agents, including natural products as well as fully synthetic compounds, with a particular focus on those that might be useful to treat AD and other tauopathies.

MT-Stabilizing Natural Products and Analogues Thereof

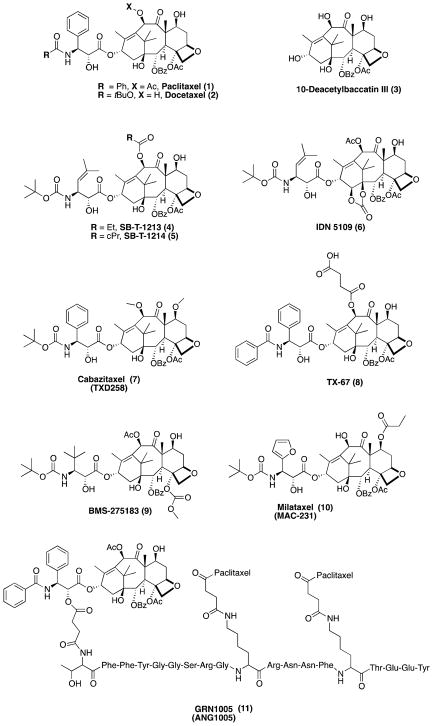

Taxanes

Paclitaxel (Taxol®, 1, Figure 3), which was isolated in the 1960s from the stem bark of the western yew, Taxus brevifolia,39 as well as from other species of the Taxus genus, was found to exhibit potent antitumor properties. The structure of paclitaxel was reported in 1971,40 but the MT-stabilizing properties of this compound remained unknown until 1979, when the Horwitz laboratory in pioneering studies demonstrated that paclitaxel is able to promote MT-assembly in vitro.41 Paclitaxel binds to the lumen (i.e., the inside) of the MT at a binding site found in the β-tubulin subunit,42 although an initial binding of this compound to the outer wall of the MT has been proposed, which may precede the translocation of this drug into the lumen of the MT.43, 44 The luminal binding site, which is commonly referred to as the taxane binding site, is also targeted by the MT-binding repeats of tau,45 and paclitaxel is found to displace tau from MTs.46 The binding of paclitaxel within the taxane site in β-tubulin is believed to promote MT-stabilization by inducing conformational changes of the M-loop of β-tubulin that result in more stable lateral interactions between adjacent protofilaments.47

Figure 3.

The structures of paclitaxel, docetaxel, 10-deacetylbaccatin III and selected examples of Pgp-insensitive taxanes.

Because of the potent anti-mitotic properties, paclitaxel has been widely used for the treatment of cancer.48 Much of the interest surrounding the MT-stabilizing class of therapeutics is arguably due to the success of paclitaxel and the closely related analogue, docetaxel (Taxotere®, 2, Figure 3) in cancer chemotherapy.49 Although paclitaxel could be obtained only in limited quantities from the bark of Taxus brevifolia, the issue of supply was elegantly solved by semi-synthesis from more readily available 10- deacetylbaccatin III (3, Figure 3).50, 51 Among the various reported tactics to obtain paclitaxel from 3 (reviewed by Kingston et al.52), the Ojima-Holton β-lactam strategy for the coupling of the phenylisoserine side-chain proved most effective.53–56 In addition to these semi-synthetic approaches, biotechnological methods of taxane production proved very effective.57

Paclitaxel was the first MT-stabilizing agent to be investigated in an animal model of neurodegenerative tauopathies, the T44 tau Tg mouse, which exhibits tau pathology in spinal motor neurons that project outside the BBB to innervate striated muscles where there is no BBB equivalent.25 However, the lack of brain penetration of paclitaxel precluded further investigations of this compound in mouse models of tauopathies that, unlike T44 tau Tg mice, more closely resemble human tauopathies with tau pathology in the brain.36 The limited ability of paclitaxel and docetaxel to diffuse across the BBB is believed to be caused at least in part by the Pgp efflux pump,58, 59 which is highly expressed in the BBB.60 Thus, taxane analogues capable of overcoming Pgp-mediated transport may result in improved brain penetration. Several examples of compounds of this type have been reported, which include: (a) weak Pgp-substrates, such as cabazitaxel32 (6, Figure 3), an FDA approved semisynthetic taxane that can saturate the active transporter;61 (b) taxoids that are also Pgp-inhibitors,62–64 such as SB-T-1213,65 SB-T-121466 and IDN-510967 (4, 5, and 6 respectively, Figure 3); and (c) taxoids that are devoid of Pgp-interactions, such as TX-6734, 68 (8, Figure 3). Among these Pgp-insensitive taxanes, 6 was found to exhibit greater brain-penetration than paclitaxel.33 Furthermore, pharmacokinetic (PK) studies with 7 revealed that drug exposure in the brain could be significantly enhanced by administering the compound via rapid infusions that resulted in plasma drug levels that are above the threshold needed to saturate Pgp.61 Other examples of taxanes capable of circumventing Pgp-mediated efflux are orally active BMS- 27518369, 70 (9, Figure 3) and milataxel,71, 72 also known as MAC-321 (10, Figure 3).

In addition to these semisynthetic taxanes, promising results have been reported with brain targeted delivery approaches. An example of this strategy is the paclitaxel-peptide conjugate, GRN100535 (11, Figure 3), a Pgp-insensitive prodrug that exploits the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1),73 which is highly expressed in the BBB, to deliver paclitaxel into the brain via receptor-mediated uptake. Compound 11 was recently reported to be active in patients with advanced solid tumors with brain metastases.74

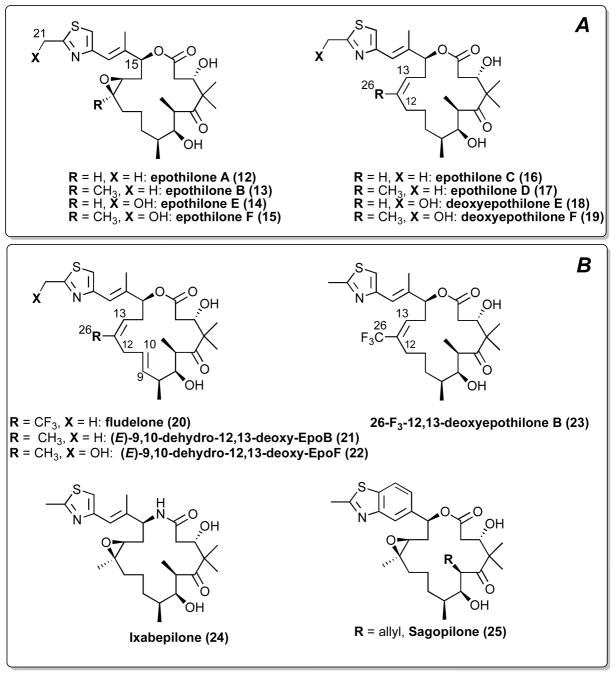

The epothilones

Epothilone A and B (12 and 13, respectively, Figure 4), originally discovered by Hofle and Reichenbach as antifungal agents produced by the soil bacterium Sorangium cellulolus,75 were later found by scientists at Merck to promote MT-assembly.76 The same studies revealed that the epothilones compete with paclitaxel for the taxane binding site on β-tubulin, suggesting that this class of compounds may act on MTs in a taxol-like manner.76 This observation led to the hypothesis that epothilones, taxanes, as well as other classes of MT-stabilizing natural products, may share a similar pharmacophore.77 NMR78 and computational studies79 supported this common pharmacophore model, however, an evaluation by electron crystallography of the complex of epothilone A with tubulin polymerized in zinc-stabilized sheets demonstrated that epothilone A and paclitaxel interact in substantially different ways within the same binding pocket in β-tubulin.80 Such differences in the binding modes provide a possible explanation as to why the epothilones, but not paclitaxel, retain generally high levels of anti-mitotic activity in cell-lines that are resistant to taxanes due to point mutations in the β-tubulin subunit.81 An additional distinctive feature of many of the epothilones is that these compounds, unlike paclitaxel and docetaxel, are active against cell lines with multi-drug resistance (MDR) caused by the overexpression of Pgp.

Figure 4.

Naturally occurring epothilones (A), and selected examples of synthetic epothilones (B).

In addition to epothilone A and B, several other naturally occurring congeners have been isolated as minor components of fermentation of myxobacteria (14–19, Figure 4 A).82 Among these, epothilone D (17, Figure 4 A) exhibited a number of promising properties, including a greater therapeutic index as a chemotherapeutic agent, compared to 13.83 Clinical trials with this compound, however, were halted due to severe side-effects, which included CNS toxicities.84 These CNS side effects are possibly the earliest evidence that 17 is a brain-penetrant compound, and reports from the patent literature indicated that this is indeed the case.85 Furthermore, in 2006 17 was reported to be effective in an animal model of schizophrenia, the STOP-null mouse model, which both lacks a MAP known as STOP (Stable Tubule Only Polypeptide) and exhibits cytoskeletal defects in CNS neurons.86 The selection of 17 as preferred candidate compound for efficacy studies in tau Tg animals followed a comparative study in which selected taxanes and epothilone D congeners, including deoxy-epothilone F87 and fludelone88 (19 and 20, respectively, Figure 4), were evaluated for their ability to diffuse across cellular membranes in vitro and enter the brain in vivo. In addition, these compounds were tested for their ability to elicit MT-stabilization in the CNS of normal mice, as determined by the elevation in acetylated α-tubulin (AcTub), which is known to be a marker of stable MTs.89, 90 Interestingly, PK studies revealed that significant concentrations of these epothilones in the brain were achieved.36 Furthermore, these studies showed that 17 exhibits a considerably longer half-life in the brain than in plasma. Similar PK properties have been described for 13.38 The ability of 17 to be retained selectively in the brain for relatively prolonged periods of time permitted infrequent (i.e., weekly) administration of the compound in efficacy studies and likely reduced the potential for systemic toxicities in tau Tg mice.26, 27

After the first total syntheses of 12 by the groups of Danishefsky,91 Nicolaou92 and Schinzer93 between 1996–97, several synthetic strategies for the efficient synthesis of epothilone analogues have been developed (for comprehensive overview, see Altmann et al.94 and references therein). Collectively, these studies enabled the synthesis and evaluation of several hundred analogues. Among these, the epothilone lactam, ixabepilone (Ixempra®, 24, Figure 4 B), was the first epothilone to receive FDA approval for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.95 Other synthetic epothilones in clinical development include sagopilone (25, Figure 4 B),96 which is characterized by the presence of the benzimidazole side-chain. Compound 25 was found to be more potent in vitro than 13, as well as highly effective in mouse tumor xenograft models.96, 97 Notably, this compound has been found to be brain-penetrant.37

Discodermolide

(+)-Discodermolide (26, Figure 5), a cytotoxic polyketide isolated by Gunasekera and co-workers from the deep-water Caribbean sponge Discodermia dissoluta,98 was initially reported to be an immunosuppressant agent.99, 100 The MT-stabilizing properties of this compound were discovered in 1996,101, 102 when it was found that 26 is even more potent than paclitaxel in promoting the nucleation phase of tubulin-assembly. Further studies revealed that discodermolide, unlike paclitaxel, retains potent anti-mitotic activity against Pgp-overexpressing cancer cell lines.103 Mechanistically, 26 was found to compete with paclitaxel for the taxane binding site on β-tubulin,102, 103 and photoaffinity labeling experiments by Horwitz, Smith and co-workers confirmed that the discodermolide binding site is in close proximity with the taxane site.104 Interestingly, the bio-active conformation of 26 is believed to be U-shaped, where the C19 side chain comes close to the lactone moiety.105 Overlays of this folded conformation of 26 and the bio-active conformation of paclitaxel highlight the similarities between the two 3D structures, supporting the possibility that both compounds adhere to a common pharmacophore.105 However, unlike paclitaxel, tubulin-bound discodermolide is thought to interact with the N-terminal H1-S2 loop106 and not with the M-loop, which is believed to be a key mediator of paclitaxel induced MT-stabilization.47 This observation suggests that the MT-stabilizing effects of paclitaxel and discodermolide may be complementary,106 thus providing an explanation for the observed synergistic effects of 26 and paclitaxel both in vitro and in vivo.107–109 Notably, 26 is the only example among the taxane site MT-stabilizing agents that shows synergy with paclitaxel.

Figure 5.

The structure of discodermolide and a biologically active, structurally simplified analogue (27).

The first total synthesis of discodermolide was reported by the Schreiber laboratory, which reported the synthesis of the natural product110 and, prior to that, the synthesis of the unnatural (−) antipode.111 Several other syntheses of 26 have been reported (reviewed by Smith and Freeze112). Notably, the gram-scale synthesis devised by Smith and co-workers, 113, 114 combined with Paterson’s first generation endgame,115 was licensed to Novartis to permit the synthesis of 60 g of material needed to conduct a Phase I clinical trial.116 In addition to discodermolide, these synthetic efforts produced numerous analogues, including discodermolide-dictyostatin117 and discodermolide-paclitaxel118 hybrid structures. Interestingly, structural changes that impede the active U-shaped conformation proved to be highly detrimental to the biological activity. On the other hand, relatively substantial structural simplifications that maintain the characteristic folded conformation of 26 produced several interesting analogues (e.g., 27, Figure 5) with biological activities comparable to the parent compound.119, 120

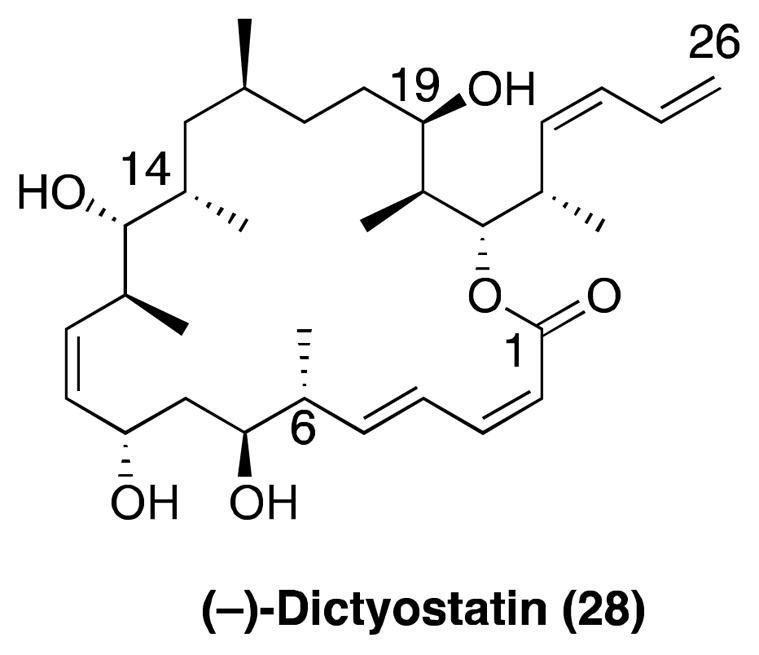

Dictyostatin

(−)-Dictyostatin (28, Figure 6), which was first isolated from a Maldives marine sponge Spongia sp. by Pettit and co-workers,121 was found to be highly potent against a variety of human cancer cell lines with a GI50 in the 50 pM to 1 nM range. The MT-stabilizing properties of this compound were reported by the Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute.122 The same studies also demonstrated that 28 is active against paclitaxel-resistant cell lines that overexpress Pgp. Competition studies revealed that 28 binds to the taxane binding site.123 Interestingly, the configurational assignment for dictyostatin is fully consistent with a common biogenesis for the structurally related, but open-chain, discodermolide. Indeed there is an exact configurational match of the C19-C26 and C6-C14 region of 28 with those at C17-C24 and C4-C12 of discodermolide, respectively. Moreover, it has been shown that the preferred conformation for 28 in solution closely resembles the conformation that was determined for discodermolide both in the solid state and in solution,124 strongly suggesting that dictyostatin and discodermolide interact in a similar fashion with the taxane binding site on β-tubulin.125, 126

Figure 6.

The structure of dictyostatin.

The first total syntheses of (−)-dictyostatin were reported concurrently by the laboratories of Paterson127 and Curran.128 Other approaches to the natural product were later reported.129–131 Dictyostatin currently represents a promising antimitotic natural product lead for development in cancer chemotherapy. To date, the ability of this compound and/or related analogues to gain access to the CNS have not been reported.

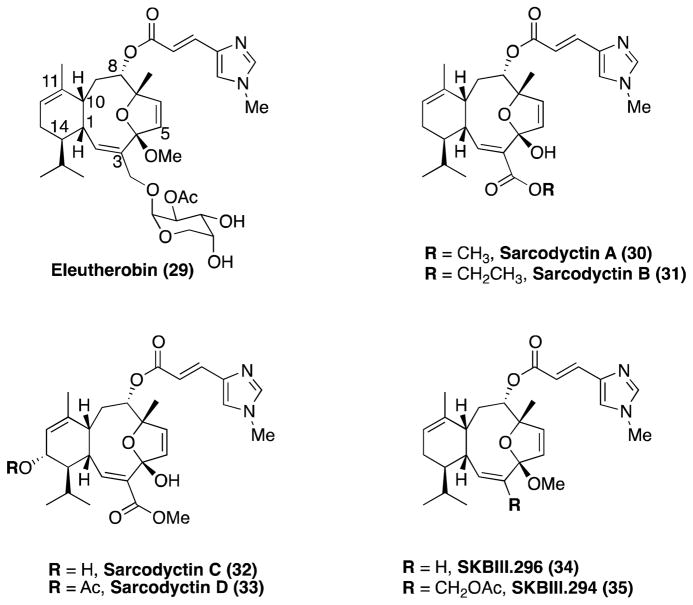

Eleutherobin, sarcodyctins and related eleuthesides

Eleutherobin132, 133 (29, Figure 7) and sarcodyctins134, 135 (30–33 Figure 7) are structurally related, coral-derived anti-mitotic agents isolated from Eleutherobia sp. and Sarcodictyon roseum, respectively. The abilities of these eleuthesides to promote MT-stabilization were described by Long et al.133 (eleutherobin) and Ciomei et al.136 (sarcodyctins). Competition binding studies revealed that these MT-stabilizing agents interact with β-tubulin at the taxane binding site.133, 137 Like paclitaxel, 29 was found to be a substrates for the Pgp.133 The carbohydrate moiety of this compound is thought to be important for the eleutherobin-Pgp interaction, as indicated by the observation that analogues lacking this fragment,138 such as SKBII.294 and SKBII.296 (34 and 35, respectively, Figure 7), did not appear to be sensitive to Pgp-mediated efflux.138

Figure 7.

Eleutherobin, sarcodyctins and selected synthetic derivatives.

Total syntheses of eleutherobin and sarcodyctins have been reported by the Nicolaou139– 142 and Danishefsky laboratories.143–145 To date, no studies describing the evaluation of these compounds in either cell or animal models of neurodegenerative tauopathy have appeared.

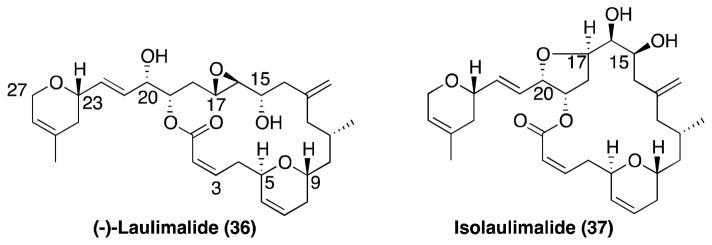

Laulimalide

Laulimalide and the rearrangement product, isolaulimalide, (36 and 37, respectively, Figure 8) were isolated from marine sponges collected in Indonesia,146 Vanatau,147 and the island of Okinawa.148 These compounds were described as cytotoxic agents; however, their mode of action was unknown until 1999, when Mooberry and co-workers reported that these compounds exhibit taxol-like MT-stabilizing properties.149 In addition, the same studies demonstrated that 36 retains strong anti-mitotic activity against cancer cell-lines overexpressing Pgp.149, 150 Interestingly, competition studies with radiolabeled or fluorescently-labeled paclitaxel revealed that 36 does not compete for the taxane binding site.150 Furthermore, consistent with this observation, 36 was found to be active against cell lines with β-tubulin mutations151 that cause resistance to both taxanes and epothilones.150 In addition, synergistic effects of laulimalide with taxane drugs have been reported.152 Taken together, these results clearly indicate the existence of a distinct tubulin binding site for this compound. Recent studies revealed that 36 binds to the exterior of the MT on β-tubulin.153

Figure 8.

Laulimalide and isolaulimalide.

Because of these promising biological activities, and because of the limited natural supply, laulimalide became an attractive synthetic target. The first total synthesis of 36 was reported by Ghosh and co-workers.154 Several other synthetic approaches, reviewed by Mulzer and Ohler,155 have been developed. Notably, scientists at the Eisai Research Institute were able to synthesize sufficient quantities of laulimalide to enable in vivo efficacy studies.156 Somewhat surprisingly, despite the promising in vitro anticancer activity, as well as PK properties, 36 did not produce a statistically significant tumor growth inhibition. The reasons for the lack of in vivo anticancer effects of laulimalide remain unclear but may be explained, at least in part, by the relatively high mitotic block reversibility ratio observed for this compound. A high reversibility of the anti-mitotic effect would imply that, in vivo, cancer cells exposed to laulimalide may resume mitosis soon after the circulating drug levels becomes sufficiently low.157 Furthermore, this lack of in vivo anticancer activity was accompanied by severe toxicities indicating that 36 may not be a viable candidate for cancer chemotherapy.157 However, subsequent studies in a different animal model demonstrated a significant inhibition of tumor growth.158

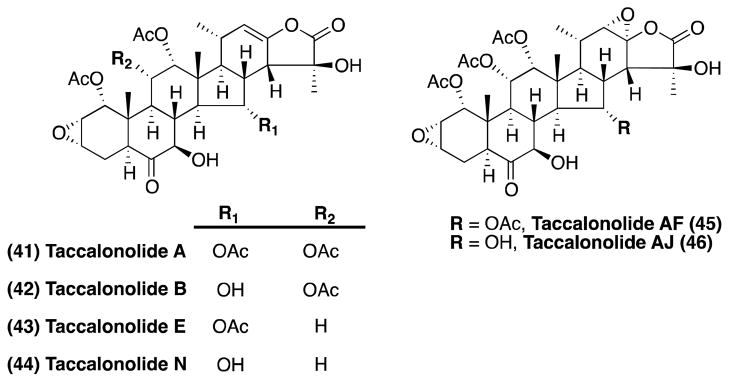

Peloruside A

Isolated in New Zealand from the marine sponge, Mycale hentscheli, peloruside A (38, Figure 9) was identified as a potent cytotoxic agent with paclitaxel like activities.159, 160 In addition to the anti-mitotic activity, this natural product was found not to be affected by the overexpression of Pgp or by tubulin mutations that are known to affect the activity of paclitaxel.161 Competition binding experiments revealed that 38 does not bind to the taxane site in β-tubulin, while the observation that laulimalide can displace 38 clearly suggests that these two compounds may have overlapping binding sites.161, 162 In line with these results, 38 did not show synergistic effects with laulimalide, but like the latter, it was found to synergize with other taxane site drugs in both polymerizing purified tubulin152 and cellular activity.163

Figure 9.

Peloruside A and B.

The first total synthesis of peloruside A was reported in 2003 by De Brandander and co-workers. 164 Several other approaches to this natural product were later developed.165–171 In addition to 38, other naturally occurring congeners have been isolated,172, 173 including peloruside B (39, Figure 9), which exhibits similar MT-stabilizing and biological activities as 38.172

Recent studies have shown that 38 protects cultured neurons against okadaic acid-induced tau phosphorylation.21 These results suggest that in addition to the epothilones, other MT-stabilizing agents, including those that do not target the taxane binding site on β-tubulin, such as peloruside and laulimalide, may be considered potential candidates for the treatment of tauopathies. However, there are presently no reports on the brain-penetration of 38.21

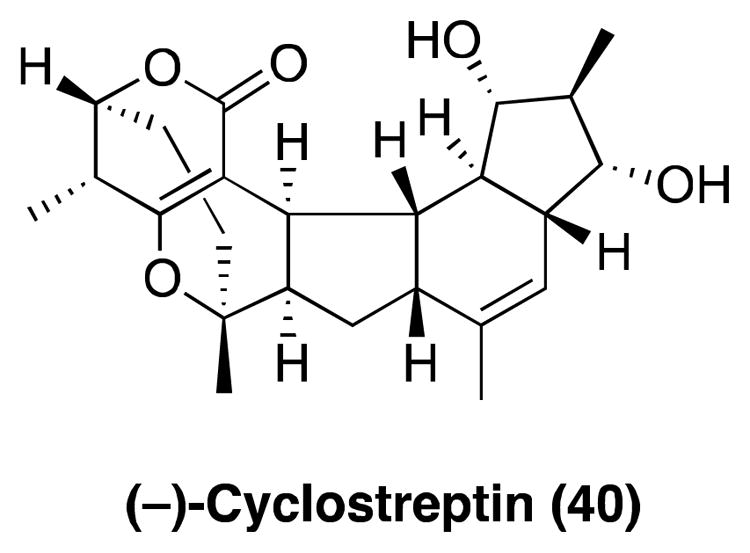

Cyclostreptin

(−)-Cyclostreptin (40, Figure 10), a bacterial natural product also known as WS9885B and FR182877, was originally identified as a compound with paclitaxel-like biological activities using a cell-based screen for novel antimitotic agents.174, 175 Structurally, 40 is characterized by an unusual ring system featuring a constrained α, β-unsaturated lactone. The natural product was initially assigned the opposite configuration.176 Total syntheses of both (+) and (−)-cyclostreptin, as reported by the laboratories of Sorensen177, 178 and Evans,179 confirmed the (−)-enantiomer to be the natural product.

Figure 10.

The structure of (−)-cyclostreptin.

Cytotoxicity studies revealed that 40, although ~10 times less potent than paclitaxel in taxol-sensitive cell-lines, is considerably more effective than paclitaxel against Pgp-overexpressing cell-lines.180 Furthermore, these studies demonstrated that 40 is not affected by tubulin mutations that are known to cause resistance to both paclitaxel and epothilone A.180 Interestingly, whereas cyclostreptin was found to be an effective competitive inhibitor of the binding of paclitaxel to MTs, significant differences were observed in the MT-stabilizing properties of these two compounds. While cyclostrept-intreated MTs are more stable to depolymerizing conditions than those resulting from paclitaxel treatment, cyclostreptin-induced MT-stabilization requires the presence of MAPs and GTP, which are not necessary for paclitaxel-induced MT-assembly.180 Subsequent studies revealed that 40 interacts covalently with specific amino acid residues of β-tubulin in both MTs and tubulin dimers. These residues are Asn228, which resides in the proximity of the taxane binding site, and Thr220 at the outer surface of a pore43 in the MT wall.181 Computational studies suggested that the covalent attachment of 40 to Thr220 may prevent the diffusion of paclitaxel and other taxane-binding drugs across the MT pore, into the taxane binding site.182 This model provides an explanation as to why 40 can prevent the binding of paclitaxel to β-tubulin despite the relatively weak tubulin polymerization properties compared to paclitaxel. Cyclostreptin is the first example of a MT-stabilizing agent found to interact irreversibly with tubulin. Similar mode of action has recently been reported for zampanolide183 (vide infra). To date, there are no reports of 40 being evaluated in cell- and/or animal-models of tauopathies; thus, it is not clear yet whether the particular mode of action of cyclostreptin, which involves covalent modification of tubulin, may be effective in restoring axonal transport deficits in neurons affected by tauopathy.

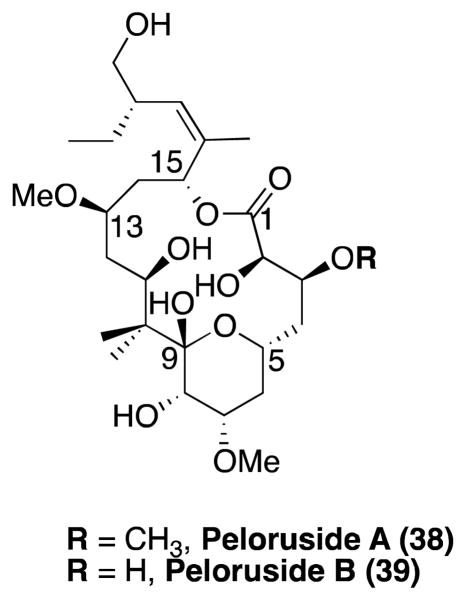

Taccalonolides

Taccalonolides are steroidal natural products that were originally isolated in 1963 from the tubers of Tacca leontopetaloides.184 The structure of these compounds was fully elucidated in 1987, when Chen and co-worker characterized taccalonolide A and B (41 and 42, respectively, Figure 11) from Tacca plantaginea.185 Since then, several other members of the taccalonolide class have been discovered (e.g., 43 and 44, Figure 11).186– 189 The MT-stabilizing properties of the taccalonolides were first recognized in 2003, when taccalonolide A and E were found to cause paclitaxel-like MT-bundling in dividing cells.190 Furthermore, the taccalonolides were found to be poor substrates for the Pgp and exhibit only limited cross-resistance with paclitaxel.190, 191

Figure 11.

Selected taccanolides.

The mode of action of this class of natural products remains an active area of investigation. Studies with 41 and 42 revealed that the taccalonolides do not bind to either tubulin or MTs,192 and that the MT-stabilizing properties of these compounds is observed only in intact cells, but not in cell extracts or purified tubulin preparations.192, 193 Recent studies, however, reported the identification of considerably more potent MT-stabilizing members of the taccalonolide family, such as taccalonolide AF and AJ (45 and 46, respectively, Figure 11), that promote MT assembly from purified tubulin.189 Further studies are needed to elucidate the mode of action of taccalonolides and evaluate the potential of taccalonolides in the context of neurodegenerative disorders. To date, there are no reports describing the total synthesis of taccalonolides.

Zampanolide and dactylolide

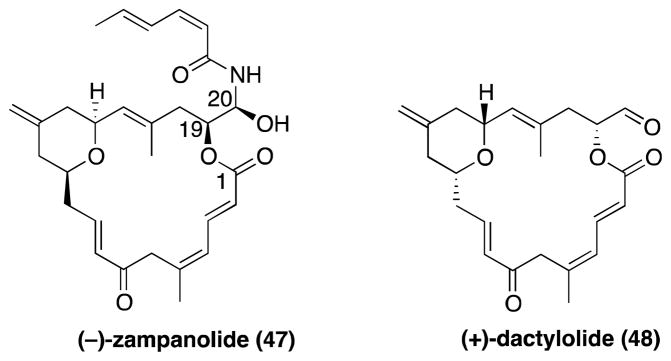

(−)-Zampanolide and (+)-dactylolide (47 and 48, respectively, Figure 12), are structurally-related natural products isolated, respectively, from Fasciospongia rimosa,194 the same sponge found in the island of Okinawa that yielded laulimalide,148 and from Dactylospongia sp.195 These two compounds share the same highly unsaturated macrolactone core but with opposite absolute configuration. In addition, zampanolide features a characteristic N-acyl hemiaminal side chain. The total synthesis and assignment of absolute configuration of both antipodes of 47 and 48 were reported first by the Smith and then Hoye laboratories.196–205

Figure 12.

The structures of naturally occurring (−)-zampanolide and (+)-dactylolide.

In 2009, 47 was reported to stabilize MTs in cells, and to promote the polymerization of purified tubulin in cell-free assays.206 The same studies revealed that 47 exhibits low nM IC50 against several cell-lines, including those that overexpress the Pgp.206 Similar MT-stabilizing properties have been described for 48,207 although this compound was found to be considerably less cytotoxic than 47, with IC50 values in the low RM range.195 Competition binding studies revealed that 47 targets the taxane site and does not interfere with the binding of laulimalide with MTs.183 Interestingly, these studies also revealed that the mode of action of 47 and 48, like cyclostreptin, involves covalent modification of specific residues (Asn228 and His229) found in the taxane binding site. However, compared to cyclostreptin, 47 is a considerably more potent MT-stabilizing agent. As in the case of cyclostreptin, the therapeutic potential of 47 as a treatment for tauopathies may be limited due to the alkylating properties of this compound.

Ceratamines

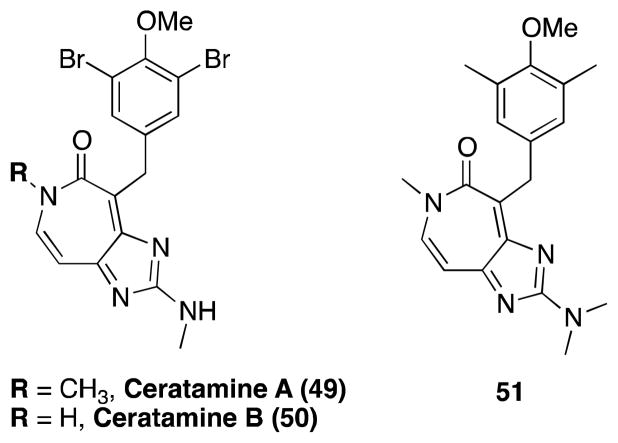

Ceratamine A and B (49 and 50, respectively, Figure 13), originally isolated from marine sponge Pseudoceratina sp. collected in Papua New Guinea, are antimitotic heterocyclic alkaloids characterized by an unusual imidazo[4,5-d]-azepine core.208

Figure 13.

The structures of naturally occurring ceratamine A and B, and of a synthetic congener (51).

These compounds were found to promote the polymerization of purified tubulin in the absence of MAPs, although less potently than paclitaxel.209 Competition binding studies revealed that the ceratamines do not act as competitive inhibitors of paclitaxel binding.209

Interestingly, ceratamines are the only non-chiral examples among all MT-stabilizing natural products. Because of this, and because of the comparatively simpler structure, ceratamines are considered as promising lead compounds for cancer chemotherapy.209 Such attributes also suggest that compounds from this class may be identified as CNS-active candidates for the treatment of tauopathies. The syntheses of the natural products have been described by Coleman and co-workers,210 with several analogues constructed and evaluated.211, 212 This effort resulted in the identification of selected derivatives (e.g., 51, Figure 13) with improved antimitotic and MT-stabilizing properties.211

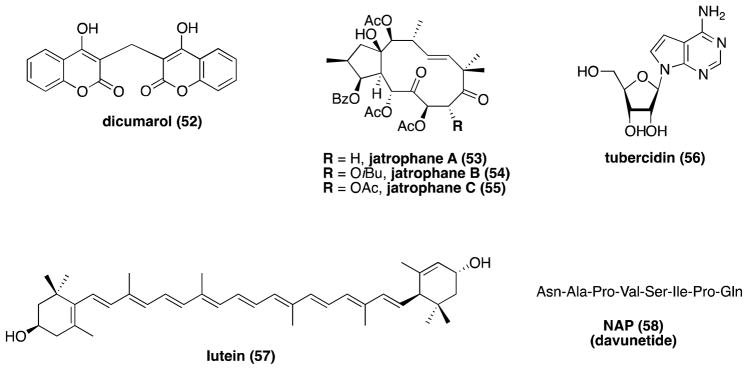

Other naturally occurring compounds with reported MT-stabilizing properties

In addition to the different classes of natural products discussed above, a number of other naturally occurring compounds, or derivatives thereof, have been reported to exhibit MT- stabilizing properties (Figure 14). These include dicumarol (52),213 jatrophanes (53– 55),214 tubercidin (56),215 xanthophylls (e.g., lutein, 57),216 as well as the NAP peptide (58), also known as davunetide, which is a short peptide fragment (NAPVSIPQ) derived from the activity-dependent neuroprotective protein (ADNP).217 However, as reported by Buey and co-workers,192 who conducted a comparative study involving different classes of MT-stabilizing agents, the MT-stabilizing properties of most of these compounds (i.e., 52–55, 57) were not confirmed. Likewise, the NAP peptide, which has been found to be neuroprotective in many different animal models (reviewed by Gozes and co-workers218– 220) and is currently in Phase II/III clinical trials for AD and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), was reported to be a MT-stabilizing agent.221, 222 However recent studies indicate that this peptide may not directly impact MT-dynamics.223

Figure 14.

Naturally products with reported MT-stabilizing properties.

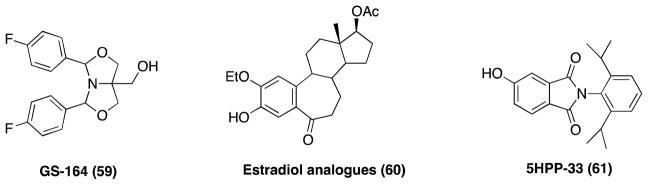

Synthetic MT-stabilizing Agents

Although the vast majority of known MT-stabilizing agents are structurally complex natural products, progress has been made in the identification of small synthetic molecules with MT-stabilizing properties. These compounds, which include GS-164 (59), identified by scientists at Takeda Chemical Industries Ltd.,224 selected estradiol derivatives,225 such as 60, and a derivative of thalidomide, 5HPP-33 (61),226 could be considered as potentially interesting leads for AD drug discovery programs (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

MT-stabilizing GS-164, estradiol derivative 60, and 5HPP-33.

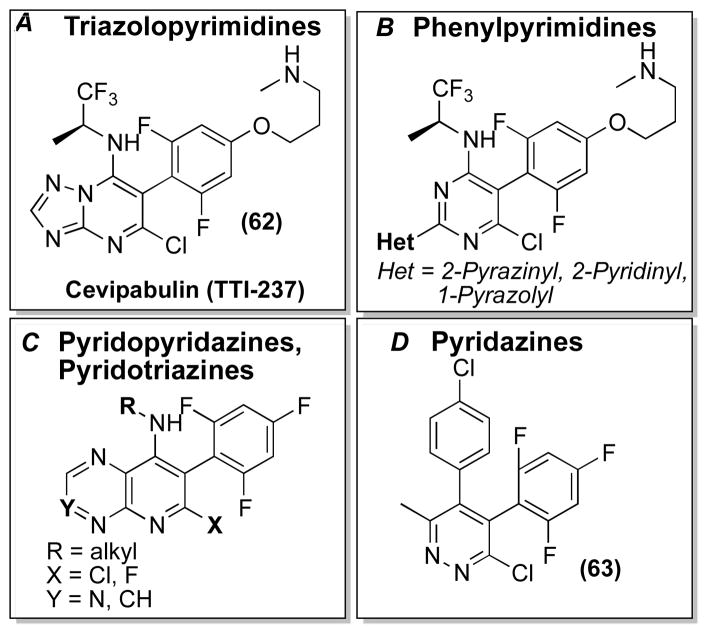

Furthermore, screening programs directed at the discovery of antifungal agents identified multiple series of synthetic mono- and di-heterocyclic compounds with MT-stabilizing properties, including certain triazolopyrimidines, typified by cevipabulin227 (also known as TTI-237, 62, Figure 16A), as well as some structurally related phenylpyrimidines228 (Figure 16B), pyridopyridazines,229 pyridotriazines230 (Figure 16C) and pyridazines231 (e.g., 63, Figure 16D).

Figure 16.

Representative mono- and di-heterocyclic MT-stabilizing agents.

Although the vast majority of these synthetic MT-stabilizing agents have been investigated only as anti-fungal agents, in recent years there have been reports of compounds of this type being explored as potential anticancer drugs. Among these, 62 displayed excellent anti-cancer activities in several nude mouse tumor xenograft models.227 Moreover, 62 was found to exhibit excellent pharmaceutical properties, including oral bioavailability, metabolic stability, and water-solubility.227 Interestingly, the mechanism by which these heterocyclic compounds promote MT-stabilization appears to be distinct from that of other classes of MT-stabilizing natural products.232, 233 In fact, radioligand binding studies demonstrated that 62 does not compete for the taxane binding site on β-tubulin.232 Instead, this compound appears to affect vinblastine binding to β-tubulin, although it is not clear yet whether this results from overlapping binding sites or a distinct allosteric cevipabulin site.232 However, in sharp contrast to the mechanism of vinblastine, vincristine and other vinca alkaloids, which de-stabilize MTs, 62 and related congeners promote the polymerization of tubulin into MTs.232, 233 Cevipabulin is currently undergoing clinical trials as an anti-cancer agent.234 However, because of the MT-stabilizing ability, favorable physical-chemical properties and synthetic accessibility, 62 and/or related analogues may hold promise in the development of CNS-active MT-stabilizing therapies.

Concluding remarks

Over the past several years, remarkable progress has been made in the development of tau focused therapies from target identification towards clinical trials for AD and related FTLD tauopathies (see Lee et al.235). Among a growing number of potentially druggable targets that could abrogate tau-mediated neurodegeneration,236 counteracting the functional loss of tau with MT-stabilizing agents is one of the most biologically and pathologically well grounded. Thus, these agents appear to be amongst the most compelling as potential treatments for neurodegenerative tauopathies. The promising results obtained from the epothilone D studies in tau Tg animal models, summarized here, provide important validation of this therapeutic strategy and, notably, have resulted in the selection of epothilone D as a clinical candidate for the treatment of AD.30

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work has been provided by the NIH/NIA (Grant AG029213)

Abbreviations used

- MT

microtubule

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- CNS

central nervous system

- FTLD

frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- PSP

progressive supranuclear palsy

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangle

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- FAT

fast axonal transport

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein

- Tg

transgenic

- MDR

multi-drug resistance

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

- B/P

brain to plasma ratio

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- PD

pharmacodynamic

- BMS

Bristol-Myers Squibb

- ADNP

activity dependent neuroprotective protein

Biographies

Carlo Ballatore is a Research Assistant Professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research. His research focuses on medicinal chemistry and drug discovery particularly in the area of Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies. He graduated in Chemistry and Pharmaceutical Technologies at University of Rome “La Sapienza”, Italy. He obtained a Ph.D. in Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Wales, Cardiff, U.K., and then did a post-doctoral fellowship at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas, Houston.

Kurt R. Brunden is Director of Drug Discovery and Research Professor in the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research (CNDR) at the University of Pennsylvania, where he oversees programs in the areas of Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration and Parkinson’s disease. Prior to joining CNDR in 2007, Dr. Brunden served as Vice President in two public biotechnology companies, leading drug discovery programs in a number of therapeutic areas. Earlier in his career, Dr. Brunden was an NIH-funded faculty member within the Biochemistry Department at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. He obtained his B.S. degree from Western Michigan University, with dual majors of Biology and Health Chemistry, and his Ph.D. in Biochemistry from Purdue University, with a post-doctoral fellowship at the Mayo Clinic.

Dr. Donna M. Huryn is an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, and Research Professor at the School of Pharmacy, University of Pittsburgh. She received a Ph.D. in Organic Chemistry from the University of Pennsylvania, then spend 18 years in the pharmaceutical industry at Hoffmann-LaRoche, Inc and Wyeth Research. At Wyeth, she led the CNS Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Sciences Interface Departments, and oversaw programs in Alzheimer’s Disease, schizophrenia, depression, multiple sclerosis and asthma. She joined academia in 2004, where her research interests lie in the identification of small molecule probes to interrogate biological pathways in the area of neurodegeneration, cancer and infectious diseases. Professor Huryn is a Fellow of the American Chemical Society.

John Q. Trojanowski obtained his MD/PhD in 1976 from Tufts University, and after training at Harvard and Penn, became Penn faculty in 1981 where he is Professor, and directs the NIA Alzheimer’s Center, the NINDS Udall Parkinson’s Center and Institute on Aging at Penn. His research focuses on neurodegenerative diseases, and he is an ISI Highly Cited Researcher (among the top 5 most highly cited neuroscientists from 1997–2007). He was elected to the Institute of Medicine in 2002 and led an effort to make a PBS film (“Alzheimer’s Disease-Facing the Facts”) that won a 2009 Emmy Award for best documentary.

Virginia M.-Y. Lee obtained her Ph.D. in Biochemistry, University of California San Francisco (1973) and an MBA at the Wharton School (1984). She is the John H. Ware 3rd Professor in Alzheimer’s Research and directs the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at the University of Pennsylvania. Her work was instrumental in demonstrating that tau, α-synuclein and TDP-43 proteins form unique brain aggregates with a central role in numerous neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, frontotemporal dementias and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. She is a member of the Institute of Medicine and her research on Alzheimer’s disease has won her numerous awards.

Amos B. Smith, III the Rhodes-Thompson Professor of Chemistry and Member of the Monell Chemical Senses Center at the University of Pennsylvania, received the first combined B.S.-M.S degree in Chemistry at Bucknell University. After a year in Medical School (Penn), he completed his Ph.D. degree (1972) and a year as Research Associate at Rockefeller; he then joined the Department of Chemistry at Penn, serving as Chair from 1988–1996. His research interests comprise the total synthesis of natural and unnatural products, development of new synthetic methods, medicinal chemistry (AIDS and Alzheimer’s diseases), peptide/peptidomimetic design and materials science. In addition, he serves as the founding Editor-in-Chief of Organic Letters, and is a fellow of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Chemical Society.

References

- 1.Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature. 1984;312:237–242. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roy S, Zhang B, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Axonal transport defects: a common theme in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2005;109:5–13. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0952-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Vos KJ, Grierson AJ, Ackerley S, Miller CC. Role of axonal transport in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:151–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee VMY, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative Tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drechsel DN, Hyman AA, Cobb MH, Kirschner MW. Modulation of the dynamic instability of tubulin assembly by the microtubule-associated protein tau. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1141–1154. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.10.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biernat J, Gustke N, Drewes G, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Phosphorylation of Ser262 strongly reduces binding of tau to microtubules: distinction between PHF-like immunoreactivity and microtubule binding. Neuron. 1993;11:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90279-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buee L, Bussiere T, Buee-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuret J, Congdon Erin E, Li Guibin, Yin Haishan, Yu Xian, Zhong Q. Evaluating triggers and enhancers of tau fibrillization. Micros Res Techniq. 2005;67:141–155. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuret J, Chirita CN, Congdon EE, Kannanayakal T, Li G, Necula M, Yin H, Zhong Q. Pathways of tau fibrillization. BBA-Mol Basis Dis. 2005;1739:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballatore C, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hempen B, Brion JP. Reduction of acetylated alpha-tubulin immunoreactivity in neurofibrillary tangle-bearing neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1996;55:964–972. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee VMY, Daughenbaugh R, Trojanowski JQ. Microtubule stabilizing drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15 (Suppl 2):S87–89. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trojanowski JQ, Smith AB, Huryn D, Lee VMY. Microtubule-stabilizing drugs for therapy of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders with axonal transport impairments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2005;6:683–686. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.5.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuji A, Tamai I. Blood-brain barrier function of P-glycoprotein. Adv Drug Del Rev. 1997;25:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2:3–14. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pardridge WM. Why is the global CNS pharmaceutical market so under-penetrated? Drug Discov Today. 2002;7:5–7. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)02082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedard PL, Di Leo A, Piccart-Gebhart MJ. Taxanes: optimizing adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:22–36. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Swain SM. Peripheral Neuropathy Induced by Microtubule-Stabilizing Agents. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1633–1642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shemesh OA, Spira ME. Rescue of neurons from undergoing hallmark tau-induced Alzheimer’s disease cell pathologies by the antimitotic drug paclitaxel. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das V, Miller JH. Microtubule stabilization by peloruside A and paclitaxel rescues degenerating neurons from okadaic acid-induced tau phosphorylation. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35:1705–1717. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michaelis ML, Ranciat N, Chen Y, Bechtel M, Ragan R, Hepperle M, Liu Y, Georg G. Protection Against beta-Amyloid Toxicity in Primary Neurons by Paclitaxel (Taxol) J Neurochem. 1998;70:1623–1627. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70041623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michaelis ML, Chen Y, Hill S, Reiff E, Georg G, Rice A, Audus K. Amyloid peptide toxicity and microtubule-stabilizing drugs. J Mol Neurosci. 2002;19:101–105. doi: 10.1007/s12031-002-0018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michaelis ML, Ansar S, Chen Y, Reiff ER, Seyb KI, Himes RH, Audus KL, Georg GI. {beta}-Amyloid-induced neurodegeneration and protection by structurally diverse microtubule-stabilizing agents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:659–68. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B, Maiti A, Shively S, Lakhani F, McDonald-Jones G, Bruce J, Lee EB, Xie SX, Joyce S, Li C, Toleikis PM, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ. Microtubule-binding drugs offset tau sequestration by stabilizing microtubules and reversing fast axonal transport deficits in a tauopathy model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunden KR, Zhang B, Carroll J, Yao Y, Potuzak JS, Hogan AM, Iba M, James MJ, Xie SX, Ballatore C, Smith AB, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Epothilone D improves microtubule density, axonal integrity, and cognition in a transgenic mouse model of tauopathy. J Neurosci. 2010;30:13861–13866. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3059-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang B, Carroll J, Trojanowski JQ, Yao Y, Iba M, Potuzak JS, Hogan AM, Xie SX, Ballatore C, Smith AB, Lee VM, Brunden KR. The microtubule-stabilizing agent, epothilone d, reduces axonal dysfunction, neurotoxicity, cognitive deficits, and Alzheimer-like pathology in an interventional study with aged tau transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3601–3611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4922-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barten DM, Fanara P, Andorfer C, Hoque N, Wong PYA, Husted KH, Cadelina GW, DeCarr LB, Yang L, Liu L, Fessler C, Protassio J, Riff T, Turner H, Janus CG, Sankaranarayanan S, Polson C, Meredith JE, Gray G, Hanna A, Olson RE, Kim SH, Vite GD, Lee FY, Albright CF. Hyperdynamic microtubules, cognitive deficits, and pathology are improved in tau transgenic mice with low doses of the microtubule-stabilizing agent BMS-241027. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7137–7145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0188-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshiyama Y, Higuchi M, Zhang B, Huang SM, Iwata N, Saido TC, Maeda J, Suhara T, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Synapse Loss and Microglial Activation Precede Tangles in a P301S Tauopathy Mouse Model. Neuron. 2007;53:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01492374?term=BMS-241027&rank=1.

- 31.Irwin DJ, White MT, Toledo JB, Xie SX, Robinson JL, Van Deerlin V, Lee VM-Y, Leverenz JB, Montine TJ, Duda JE, Hurtig HI, Trojanowski JQ. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson’s disease dementia. Ann Neurol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/ana.23659. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galsky MD, Dritselis A, Kirkpatrick P, Oh WK. Cabazitaxel. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:677–678. doi: 10.1038/nrd3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laccabue D, Tortoreto M, Veneroni S, Perego P, Scanziani E, Zucchetti M, Zaffaroni M, D’Incalci M, Bombardelli E, Zunino F, Pratesi G. A novel taxane active against an orthotopically growing human glioma xenograft. Cancer. 2001;92:3085–3092. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011215)92:12<3085::aid-cncr10150>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice A, Liu Y, Michaelis ML, Himes RH, Georg GI, Audus KL. Chemical modification of paclitaxel (Taxol) reduces P-glycoprotein interactions and increases permeation across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in situ. J Med Chem. 2005;48:832–838. doi: 10.1021/jm040114b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regina A, Demeule M, Che C, Lavallee I, Poirier J, Gabathuler R, Beliveau R, Castaigne JP. Antitumour activity of ANG1005, a conjugate between paclitaxel and the new brain delivery vector Angiopep-2. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:185–197. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brunden KR, Yao Y, Potuzak JS, Ferrer NI, Ballatore C, James MJ, Hogan AM, Trojanowski JQ, Smith AB, Lee VM. The characterization of microtubule-stabilizing drugs as possible therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease and related tauopathies. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:341–351. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoffmann J, Fichtner I, Lemm M, Lienau P, Hess-Stumpp H, Rotgeri A, Hofmann B, Klar U. Sagopilone crosses the blood-brain barrier in vivo to inhibit brain tumor growth and metastases. Neuro Oncol. 2009;11:158–166. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-072). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Reilly T, Wartmann M, Brueggen J, Allegrini PR, Floersheimer A, Maira M, McSheehy PM. Pharmacokinetic profile of the microtubule stabilizer patupilone in tumor-bearing rodents and comparison of anti-cancer activity with other MTS in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:1045–1054. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wall ME, Wani MC. Paper No. M-006. 153rd National Meeting of the American Chemical Society; Miami Beach, Fla. 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:2325–2327. doi: 10.1021/ja00738a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by taxol. Nature. 1979;277:665–667. doi: 10.1038/277665a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nogales E, Wolf SG, Khan IA, Luduena RF, Downing KH. Structure of tubulin at 6. 5 A and location of the taxol-binding site. Nature. 1995;375:424–427. doi: 10.1038/375424a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Díaz JF, Barasoain I, Andreu JM. Fast Kinetics of Taxol Binding to Microtubules. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8407–8419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barasoain I, Garcia-Carril AM, Matesanz R, Maccari G, Trigili C, Mori M, Shi JZ, Fang WS, Andreu JM, Botta M, Diaz JF. Probing the Pore Drug Binding Site of Microtubules with Fluorescent Taxanes: Evidence of Two Binding Poses. Chem Biol. 2010;17:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amos LA. Microtubule structure and its stabilisation. Org Biomol Chem. 2004;2:2153–2160. doi: 10.1039/b403634d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samsonov A, Yu JZ, Rasenick M, Popov SV. Tau interaction with microtubules in vivo. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:6129–6141. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amos LA, Lowe J. How Taxol stabilises microtubule structure. Chem Biol. 1999;6:R65–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)89002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisenhauer EA, Vermorken JB. The Taxoids: Comparative Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutic Potential. Drugs. 1998;55:5–30. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199855010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Denis JN, Greene AE, Guenard D, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Mangatal L, Potier P. Highly efficient, practical approach to natural taxol. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:5917–5919. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guenard D, Gueritte-Voegelein F, Potier P. Taxol and taxotere: discovery, chemistry, and structure-activity relationships. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kingston DG, Jagtap PG, Yuan H, Samala L. The chemistry of taxol and related taxoids. Fortschr Chem Org Naturst. 2002;84:53–225. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6160-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ojima I. Recent Advances in the .beta.-Lactam Synthon Method. Acc Chem Res. 1995;28:383–389. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ojima I, Habus I, Zhao M, Zucco M, Park YH, Sun CM, Brigaud T. New and efficient approaches to the semisynthesis of taxol and its C-13 side chain analogs by means of β-lactam synthon method. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:6985–7012. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Georg GI, Cheruvallath ZS, Himes RH, Mejillano MR, Burke CT. Synthesis of biologically active taxol analogs with modified phenylisoserine side chains. J Med Chem. 1992;35:4230–4237. doi: 10.1021/jm00100a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holton RA. US005175315A Method for preparation of taxol using beta lactam. 1992

- 57.Exposito O, Bonfill M, Moyano E, Onrubia M, Mirjalili MH, Cusido RM, Palazon J. Biotechnological production of taxol and related taxoids: current state and prospects. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:109–121. doi: 10.2174/187152009787047761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kemper EM, van Zandbergen AE, Cleypool C, Mos HA, Boogerd W, Beijnen JH, van Tellingen O. Increased Penetration of Paclitaxel into the Brain by Inhibition of P-Glycoprotein. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2849–2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fellner S, Bauer B, Miller DS, Schaffrik M, Fankhanel M, Spruss T, Bernhardt G, Graeff C, Farber L, Gschaidmeier H, Buschauer A, Fricker G. Transport of paclitaxel (Taxol) across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1309–1318. doi: 10.1172/JCI15451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beaulieu E, Demeule M, Ghitescu L, Beliveau R. P-glycoprotein is strongly expressed in the luminal membranes of the endothelium of blood vessels in the brain. Biochem J. 1997;326 ( Pt 2):539–544. doi: 10.1042/bj3260539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouchet BP, Galmarini CM. Cabazitaxel, a new taxane with favorable properties. Drugs Today (Barc) 2010;46:735–742. doi: 10.1358/dot.2010.46.10.1519019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferlini C, Distefano M, Pignatelli F, Lin S, Riva A, Bombardelli E, Mancuso S, Ojima I, Scambia G. Antitumour activity of novel taxanes that act at the same time as cytotoxic agents and P-glycoprotein inhibitors. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1762–1768. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vredenburg MR, Ojima I, Veith J, Pera P, Kee K, Cabral F, Sharma A, Kanter P, Greco WR, Bernacki RJ. Effects of orally active taxanes on P-glycoprotein modulation and colon and breast carcinoma drug resistance. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1234–1245. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.16.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Minderman H, Brooks TA, O’Loughlin KL, Ojima I, Bernacki RJ, Baer MR. Broad-spectrum modulation of ATP-binding cassette transport proteins by the taxane derivatives ortataxel (IDN-5109, BAY 59-8862) and tRA96023. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0745-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ojima I, Slater JC, Michaud E, Kuduk SD, Bounaud PY, Vrignaud P, Bissery MC, Veith JM, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. Syntheses and structure-activity relationships of the second-generation antitumor taxoids: exceptional activity against drug-resistant cancer cells. J Med Chem. 1996;39:3889–3896. doi: 10.1021/jm9604080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ojima I, Chen J, Sun L, Borella CP, Wang T, Miller ML, Lin S, Geng X, Kuznetsova L, Qu C, Gallager D, Zhao X, Zanardi I, Xia S, Horwitz SB, Mallen-St Clair J, Guerriero JL, Bar-Sagi D, Veith JM, Pera P, Bernacki RJ. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new-generation taxoids. J Med Chem. 2008;51:3203–3221. doi: 10.1021/jm800086e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Distefano M, Scambia G, Ferlini C, Gaggini C, De Vincenzo R, Riva A, Bombardelli E, Ojima I, Fattorossi A, Panici PB, Mancuso S. Anti-proliferative activity of a new class of taxanes (14beta-hydroxy-10-deacetylbaccatin III derivatives) on multidrug-resistance-positive human cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:844–850. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970904)72:5<844::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rice A, Michaelis M, Georg G, Liu Y, Turunen B, Audus K. Overcoming the blood-brain barrier to taxane delivery for neurodegenerative diseases and brain tumors. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20:339–343. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mastalerz H, Cook D, Fairchild CR, Hansel S, Johnson W, Kadow JF, Long BH, Rose WC, Tarrant J, Wu MJ, Xue MQ, Zhang G, Zoeckler M, Vyas DM. The discovery of BMS-275183: an orally efficacious novel taxane. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:4315–4323. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(03)00495-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rose WC, Long BH, Fairchild CR, Lee FY, Kadow JF. Preclinical pharmacology of BMS-275183; an orally active taxane. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2016–2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sampath D, Discafani CM, Loganzo F, Beyer C, Liu H, Tan X, Musto S, Annable T, Gallagher P, Rios C, Greenberger LM. MAC-321, a novel taxane with greater efficacy than paclitaxel and docetaxel in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer There. 2003;2:873–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lockhart AC, Bukowski R, Rothenberg ML, Wang KK, Cooper W, Grover J, Appleman L, Mayer PR, Shapiro M, Zhu AX. Phase I trial of oral MAC-321 in subjects with advanced malignant solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60:203–209. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0362-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Demeule M, Regina A, Che C, Poirier J, Nguyen T, Gabathuler R, Castaigne JP, Beliveau R. Identification and design of peptides as a new drug delivery system for the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:1064–1072. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.131318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kurzrock R, Gabrail N, Chandhasin C, Moulder S, Smith C, Brenner A, Sankhala K, Mita A, Elian K, Bouchard D, Sarantopoulos J. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and activity of GRN1005, a novel conjugate of angiopep-2, a peptide facilitating brain penetration, and paclitaxel, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:308–316. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hofle G, Reichenbach H. Anticancer agents from natural products. CRC Press LLC; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. Anticancer agents from natural products; pp. 413–450. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bollag DM, McQueney PA, Zhu J, Hensens O, Koupal L, Liesch J, Goetz M, Lazarides E, Woods CM. Epothilones, a new class of microtubule-stabilizing agents with a taxol-like mechanism of action. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2325–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ojima I, Chakravarty S, Inoue T, Lin S, He L, Horwitz SB, Kuduk SD, Danishefsky SJ. A common pharmacophore for cytotoxic natural products that stabilize microtubules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4256–4261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Reese M, Sanchez-Pedregal VM, Kubicek K, Meiler J, Blommers MJJ, Griesinger C, Carlomagno T. Structural Basis of the Activity of the Microtubule-Stabilizing Agent Epothilone A Studied by NMR Spectroscopy in Solution. Angewandte Chemie. 2007;119:1896–1900. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Forli S, Manetti F, Altmann KH, Botta M. Evaluation of novel epothilone analogues by means of a common pharmacophore and a QSAR pseudoreceptor model for taxanes and epothilones. ChemMedChem. 2010;5:35–40. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nettles JH, Li H, Cornett B, Krahn JM, Snyder JP, Downing KH. The binding mode of epothilone A on alpha,beta-tubulin by electron crystallography. Science. 2004;305:866–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1099190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Giannakakou P, Sackett DL, Kang YK, Zhan Z, Buters JT, Fojo T, Poruchynsky MS. Paclitaxel-resistant human ovarian cancer cells have mutant beta-tubulins that exhibit impaired paclitaxel-driven polymerization. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17118–17125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.17118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hardt IH, Steinmetz H, Gerth K, Sasse F, Reichenbach H, Hofle G. New natural epothilones from Sorangium cellulosum, strains So ce90/B2 and So ce90/D13: isolation, structure elucidation, and SAR studies. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:847–856. doi: 10.1021/np000629f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kolman A. Epothilone D (Kosan/Roche) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:657–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Beer TM, Higano CS, Saleh M, Dreicer R, Hudes G, Picus J, Rarick M, Fehrenbacher L, Hannah AL. Phase II study of KOS-862 in patients with metastatic androgen independent prostate cancer previously treated with docetaxel. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:565–570. doi: 10.1007/s10637-007-9068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lichtner RM, Rotgeri A, Klar U, Hoffmann J, Buchmann B, Schwede W, Skuballa W. WO 03/074053 A1. The use of epothilones in the treatment of brain diseases associated with proliferative process. 2003

- 86.Andrieux A, Salin P, Schweitzer A, Begou M, Pachoud B, Brun P, Gory-Faure S, Kujala P, Suaud-Chagny MF, Hofle G, Job D. Microtubule Stabilizer Ameliorates Synaptic Function and Behavior in a Mouse Model for Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1224–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee CB, Wu Z, Zhang F, Chappell MD, Stachel SJ, Chou TC, Guan Y, Danishefsky SJ. Insights into long-range structural effects on the stereochemistry of aldol condensations: a practical total synthesis of desoxyepothilone F. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5249–5259. doi: 10.1021/ja010039j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rivkin A, Yoshimura F, Gabarda AE, Cho YS, Chou TC, Dong H, Danishefsky SJ. Discovery of (E)-9,10-dehydroepothilones through chemical synthesis: on the emergence of 26-trifluoro-(E)-9,10-dehydro-12,13-desoxyepothilone B as a promising anticancer drug candidate. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10913–10922. doi: 10.1021/ja046992g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Laferriere N, MacRae T, Brown D. Tubulin synthesis and assembly in differentiating neurons. Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;75:103–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Black M, Baas P, Humphries S. Dynamics of alpha-tubulin deacetylation in intact neurons. J Neurosci. 1989;9:358–368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-01-00358.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Balog A, Meng D, Kamenecka T, Bertinato P, Su DS, Sorensen EJ, Danishefsky SJ. Total Synthesis of (−)-Epothilone A. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1996;35:2801–2803. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yang Z, He Y, Vourloumis D, Vallberg H, Nicolaou KC. Total Synthesis of Epothilone A: The Olefin Metathesis Approach. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:166–168. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schinzer D, Limberg A, Bauer A, Bohm OM, Cordes M. Total Synthesis of (−)-Epothilone A. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1997;36:523–524. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Altmann K-H, Hofle G, Muller R, Mulzer JKP. Epothilones: An Outstanding Family of Anti-Tumor Agents. Springer; Wien New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Conlin A, Fornier M, Hudis C, Kar S, Kirkpatrick P. Ixabepilone. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:953–954. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Klar U, Buchmann B, Schwede W, Skuballa W, Hoffmann J, Lichtner RB. Total synthesis and antitumor activity of ZK-EPO: the first fully synthetic epothilone in clinical development. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:7942–7948. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Klar U, Hoffmann J, Giurescu M. Sagopilone (ZK-EPO): from a natural product to a fully synthetic clinical development candidate. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1735–1748. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.11.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gunasekera SP, Gunasekera M, Longley RE, Schulte GK. Discodermolide: a new bioactive polyhydroxylated lactone from the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. J Org Chem. 1990;55:4912–4915. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Longley RE, Caddigan D, Harmody D, Gunasekera M, Gunasekera SP. Discodermolide--a new, marine-derived immunosuppressive compound. I. In vitro studies. Transplantation. 1991;52:650–656. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199110000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Longley RE, Caddigan D, Harmody D, Gunasekera M, Gunasekera SP. Discodermolide--a new, marine-derived immunosuppressive compound. II. In vivo studies. Transplantation. 1991;52:656–661. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199110000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.ter Haar E, Kowalski RJ, Hamel E, Lin CM, Longley RE, Gunasekera SP, Rosenkranz HS, Day BW. Discodermolide, a cytotoxic marine agent that stabilizes microtubules more potently than taxol. Biochemistry. 1996;35:243–250. doi: 10.1021/bi9515127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hung DT, Chen J, Schreiber SL. (+)-Discodermolide binds to microtubules in stoichiometric ratio to tubulin dimers, blocks taxol binding and results in mitotic arrest. Chem Biol. 1996;3:287–293. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kowalski RJ, Giannakakou P, Gunasekera SP, Longley RE, Day BW, Hamel E. The microtubule-stabilizing agent discodermolide competitively inhibits the binding of paclitaxel (Taxol) to tubulin polymers, enhances tubulin nucleation reactions more potently than paclitaxel, and inhibits the growth of paclitaxel-resistant cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:613–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xia S, Kenesky CS, Rucker PV, Smith AB, Orr GA, Horwitz SB. A photoaffinity analogue of discodermolide specifically labels a peptide in beta-tubulin. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11762–11775. doi: 10.1021/bi060497a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Martello LA, LaMarche MJ, He L, Beauchamp TJ, Smith AB, 3rd, Horwitz SB. The relationship between Taxol and (+)-discodermolide: synthetic analogs and modeling studies. Chem Biol. 2001;8:843–855. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Khrapunovich-Baine M, Menon V, Verdier-Pinard P, Smith AB, Angeletti RH, Fiser A, Horwitz SB, Xiao H. Distinct pose of discodermolide in taxol binding pocket drives a complementary mode of microtubule stabilization. Biochemistry. 2009;48:11664–11677. doi: 10.1021/bi901351q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Honore S, Kamath K, Braguer D, Horwitz SB, Wilson L, Briand C, Jordan MA. Synergistic suppression of microtubule dynamics by discodermolide and paclitaxel in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4957–4964. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Martello LA, McDaid HM, Regl DL, Yang CP, Meng D, Pettus TR, Kaufman MD, Arimoto H, Danishefsky SJ, Smith AB, 3rd, Horwitz SB. Taxol and discodermolide represent a synergistic drug combination in human carcinoma cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1978–1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Huang GS, Lopez-Barcons L, Freeze BS, Smith AB, III, Goldberg GL, Horwitz SB, McDaid HM. Potentiation of Taxol Efficacy by Discodermolide in Ovarian Carcinoma Xenograft-Bearing Mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:298–304. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hung DT, Nerenberg JB, Schreiber SL. Syntheses of Discodermolides Useful for Investigating Microtubule Binding and Stabilization. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11054–11080. [Google Scholar]