Background: Phosphorylation of Tyr in the 310 helix of p27 reduces its inhibitory activity on cyclin-CDK complexes.

Results: Mutation of this site to Phe reduces the tumor-promoting activity of p21 in the RCAS-PDGF-HA/nestin-TvA mouse model of proneural gliomagenesis.

Conclusion: Tyr phosphorylation of p21 contributes to its oncogenic role.

Significance: This mouse model establishes the significance of this modification for the nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1-CDK4.

Keywords: Animal Models, Cancer Biology, CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Cell Proliferation, Glioblastoma, RCAS-PDGF-HA/nestin-TvA Mouse Model, CDK Inhibitors, p21Waf1/Cip1, Proneural Glioma, Tyrosine Phosphorylation

Abstract

Phosphorylation of Tyr-88/Tyr-89 in the 310 helix of p27 reduces its cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitory activity. This modification does not affect the interaction of p27 with cyclin-CDK complexes but does interfere with van der Waals and hydrogen bond contacts between p27 and amino acids in the catalytic cleft of the CDK. Thus, it had been suggested that phosphorylation of this site could switch the tumor-suppressive CDK inhibitory activity to an oncogenic activity. Here, we examined this hypothesis in the RCAS-PDGF-HA/nestin-TvA proneural glioma mouse model, in which p21 facilitates accumulation of nuclear cyclin D1-CDK4 and promotes tumor development. In these tumor cells, approximately one-third of the p21 is phosphorylated at Tyr-76 in the 310 helix. Mutation of this residue to glutamate reduced inhibitory activity in vitro. Mutation of this residue to phenylalanine reduced the tumor-promoting activity of p21 in the animal model, whereas glutamate or alanine substitution allowed tumor formation. Consequently, we conclude that tyrosine phosphorylation contributes to the conversion of CDK inhibitors from tumor-suppressive roles to oncogenic roles.

Introduction

The Cip/Kip cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)4 inhibitors p21 and p27 were discovered by their ability to bind and inhibit cyclin G1-dependent kinases (1). These proteins have a conserved N-terminal kinase inhibitory domain and a less conserved C-terminal domain that interacts with other proteins. However, soon after their original identification in growth-arrested cells, a number of reports indicated that these proteins also bound to active cyclin G1-CDK complexes in both growing tumor cells and primary cells (2–8). Recently, a number of groups independently showed that phosphorylation of Tyr-88/Tyr-89 can reduce the inhibitory activity of p27 (9–12). Structural and biochemical studies suggest that phosphorylation at this site reduces the formation of van der Waals and hydrogen bond contacts with amino acids in the catalytic cleft of the CDK (13–15). This may allow the bound cyclin-CDK2 complex to phosphorylate residues, promoting p27 ubiquitination and turnover (9, 10), and may allow p27 to interact with cyclin D1-CDK4, preventing its Crm1-dependent nuclear export (16, 17) while retaining its kinase activity. Thus, tyrosine phosphorylation might switch the role of p27 from inhibiting tumor growth to facilitating tumor growth. However, there are no mouse models in which p27 is required for tumor development, making it difficult to assess the significance of this modification in a quantitative way.

The RCAS-PDGF-HA/nestin-TvA model of proneural glioma is an exceptional venue in which to examine the importance of tyrosine phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor in tumor development. In this model, nestin-positive stem and progenitor cells (18) are engineered to express the avian retroviral receptor TvA. These cells can be infected by an avian retrovirus (RCAS) that expresses PDGF or other genes (19, 20). Expression of PDGF in these cells induces glioma that recapitulates the hallmarks of proneural tumors with nearly complete penetrance (21–24). In this model, tumor development is largely dependent on p21. Using genetic complementation in the animal and molecular analysis of cell lines, we showed that this growth-promoting activity of p21 was related to its ability to bind cyclin D1-CDK4 and induce its nuclear accumulation (25). Thus, the model has all of the characteristics necessary to test the hypothesis that tyrosine phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor contributes to its conversion from a growth suppressor to a tumor promoter affecting cyclin-CDK inhibitory activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Protein Extraction

YH/J12, DF1, 293T cells and human EGF receptor (EGFR) and PDGF receptor (PDGFR) tumorspheres were cultured in DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum and 2 mm glutamine as described previously (25). Nearly confluent cultures (∼70–80%) of YH/J12 cells were treated for 18 h with 5 mm PP2. Extracts for p21 binding assays were prepared from 293T cells lysed in 20 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mm KCl, and 0.5 mm MgCl2) + 0.1 m NaCl as described (26).

To determine the localization and half-life of p21 and the different mutants, 293T cells were transfected with expression vectors by calcium phosphate methods, and immunofluorescence was carried out as described (25). Transfected cells were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide to determine protein half-life.

Antibodies and Enzymes

Antibodies against p21 (F-5), CDK4 (C-22), and cyclin D1 (A-12) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against phospho-Tyr-416 Src and phosphotyrosine (monoclonal 4G10) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. Antibodies against Src (clone GD11) were purchased from Millipore. Src and Abl kinases were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. Calf intestine alkaline phosphatase was purchased from New England Biolabs.

Immunoblot and Immunoprecipitation Kinase Assays

Cell extracts were prepared in Rb kinase buffer as described (26). 1 mg of extract was used for each immunoprecipitation, and the immunoprecipitate was divided into thirds for immunoblotting as described (26). 75 mm Phos-tag reagent (Wako) and 75 mm MnCl2 were included in the resolving gel. Prior to transferring the proteins from the Phos-tag-containing gels to PVDF membranes for immunoblotting, the gel was soaked in 25 mm Tris (pH 7.6) containing 20% isopropyl alcohol and 1 mm EDTA for 30 min and then in the same buffer without EDTA for an additional 10 min. Immunoblotting was performed as described (7).

Cyclin D1 and p21 immunoprecipitation kinase assays were performed with 1 mg of extract exactly as described (25). Quantitation was done using Image Gauge software.

Abl Kinase Assays

200 ng of recombinant Abl1 (Cell Signaling 7904) was incubated with 2 μg of recombinant p21 and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP in Abl1 kinase buffer (60 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm MnCl2, 3 mm sodium orthovanadate, 1 mm DTT, and 30 mm ATP) for 2 h at 37 °C. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 4× SDS sample buffer and heated to 95 °C for 5 min before loading one-half of the reaction onto a conventional SDS-polyacrylamide gel and the other half onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel supplemented with Phos-tag reagent. Kinase activity was detected by autoradiography or phosphorimaging. Quantitation was done using Image Gauge software.

CDK Inhibition Assays

Anti-cyclin D1 immunoprecipitates from Hi5 cells co-infected with baculoviruses expressing cyclin D1 and CDK4 (11) were combined with increasing amounts of His-tagged p21(Y76F) or p21(Y76E) isolated from Escherichia coli by a denaturation-renaturation protocol, and the effect of the CDK inhibitor was assessed by kinase assays using Rb as a substrate as described (25).

800 ng of His-p21 isolated from E. coli was phosphorylated with 30 ng of recombinant Abl kinase in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-Cl (pH 7.0), 10 mm MgCl2, and 200 mm ATP for 1 h at room temperature. Some reactions were supplemented with 10 μCi of radiolabeled [32P]ATP as well. Phosphorylated proteins were incubated with cyclin D1-CDK4 complexes produced in Hi5 cells (11), and p21 and the associated proteins were affinity-purified on TALON beads. The amounts of p21-associated CDK4, His-tagged p21, and p21-associated Rb kinase activities were measured by immunoblotting and autoradiography (11).

RCAS/TvA Mouse Modeling

These experiments were performed exactly as described by Liu et al. (25). We graded the tumors as described (27).

RESULTS

Phosphorylation of p21 at Tyr-76 in PDGF-transformed Glial Cells

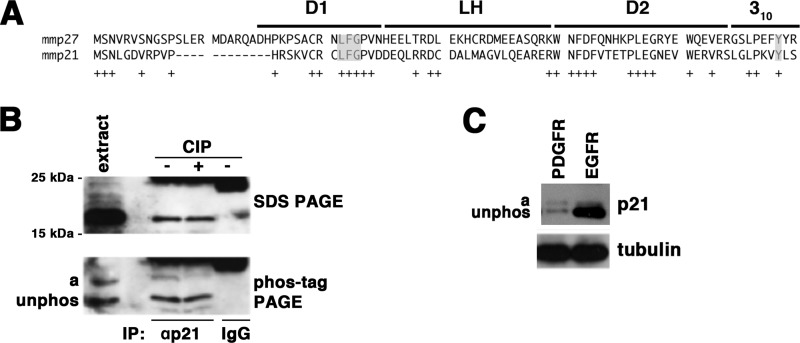

In cycling cells, phosphorylation of p27 at Tyr-88/Tyr-89 prevents the complete folding of the protein into an inhibitory complex on cyclin G1-CDK complexes (9–12). In gliomas characterized by aberrant PDGF signaling, p27 is a CDK2 inhibitor, whereas the structurally related Kip-type CDK inhibitor p21 is growth-promoting (25, 28). As a tyrosine is conserved in the 310 helix (Fig. 1A), we wanted to assess whether it was phosphorylated on p21 in a PDGF-induced glioma cell line. To accomplish this, we prepared extracts from YH/J12 cells and resolved the proteins by Phos-tag/SDS gel electrophoresis and detected endogenous p21 by immunoblotting. YH/J12 is a spontaneously immortalized PDGF-expressing cell line derived from the infection of nestin-TvA transgenic whole brain cell cultures with the avian retrovirus RCAS expressing the PDGF oncogene (29). These cells faithfully recapitulate the molecular regulation of the proliferative properties of a proneural subtype of glioma (25, 28). Phos-tag is a cationic compound that, when mixed into SDS-polyacrylamide gels, retards the migration of phosphorylated protein. Under these conditions, p21 migrated as two prominent species (Fig. 1B, band a and unphos). The slower migrating band (band a) was reduced by phosphatase treatment, confirming that this band was phosphorylated p21. We quantitated the amount of phosphorylated p21 (band a) relative to total p21 (band a + unphos) in cycling YH/J12 cells and found that one-third (33.5 ± 1.7%) of the p21 in cycling YH/J12 cells was phosphorylated at steady state.

FIGURE 1.

Phosphorylation of p21 in cycling cells. A, alignment of the human and mouse N-terminal kinase inhibitory domains of p21 and p27. Subdomains D1, LH, and D2 and the 310 helix are noted as described (14). Conserved residues are indicated below (+). The conserved cyclin-binding LFG motif and the Tyr in the 310 helix are highlighted in gray. B, extracts and immunoprecipitates (IP) with either anti-p21 antibodies or rabbit nonspecific IgG from YH/J12 cells were resolved by SDS-PAGE or Phos-tag-PAGE as indicated and blotted for p21. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the left of the SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the migration of p21 into two isoforms is indicated on the left of the Phos-tag polyacrylamide gel. Calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIP) treatment of the immunoprecipitate is noted above the relevant lanes. C, extracts from a growing PDGFRA-driven human proneural tumorsphere and an EGFR-driven human mesenchymal tumorsphere were divided in two and resolved by Phos-tag/SDS-PAGE or conventional SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes, and p21 and tubulin were detected by immunoblotting, respectively. The separation between unphosphorylated and phosphorylated p21 in human cells is smaller than that observed in mouse cells because unphosphorylated human p21 migrates more slowly than mouse p21.

p21 facilitates growth of a subgroup of PDGF-induced proneural gliomas, whereas in EGFR-induced mesenchymal glioma, p21 inhibits growth (30). Thus, we asked if the amount of phosphorylated p21 correlates with its growth inhibitory activity. Two tumorsphere cell lines characterized either by PDGFR amplification and a high proneural gene expression pattern or by EGFR amplification and a high mesenchymal gene expression pattern (31) were obtained, and the level of p21 was measured by immunoblotting after electrophoresis on Phos-tag-containing SDS-polyacrylamide gels. The total amount of p21 was greater in the EGFR cell line, but the ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated protein was higher in the PDGF-induced cell line (Fig. 1C). Thus, the ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated protein correlates with the growth-promoting activity of p21.

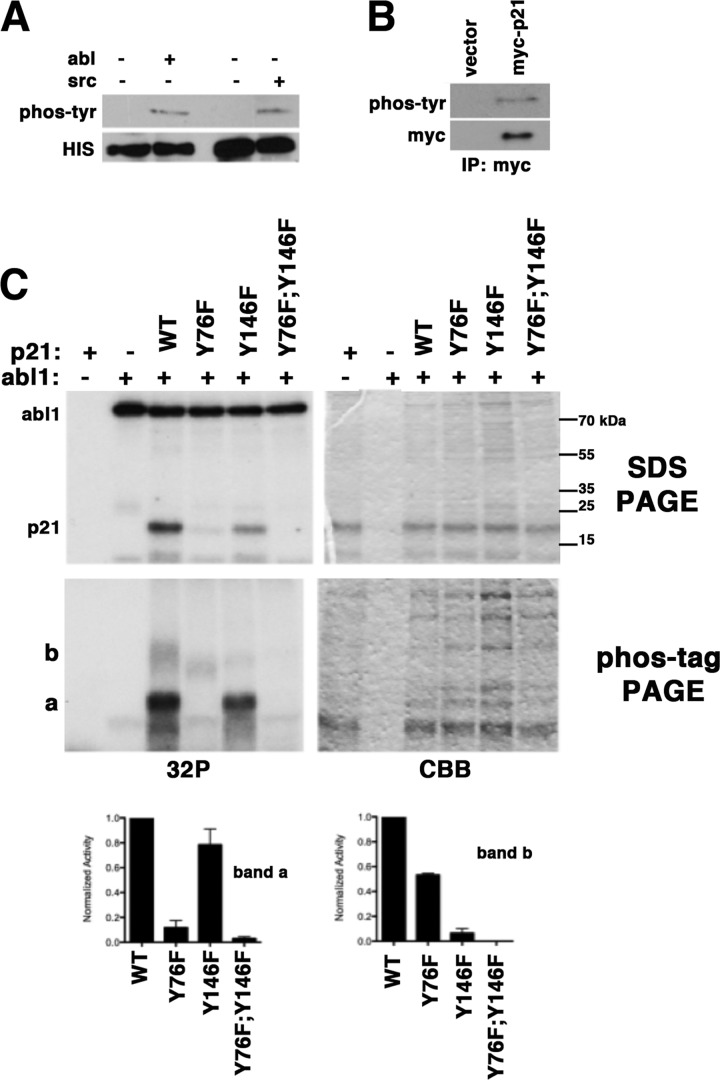

Src and Abl kinases act downstream of PDGFR. Recombinant p21 could be phosphorylated by either Src or Abl kinase in vitro (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, Myc-tagged p21 expressed in YH/J12 cells was also phosphorylated at tyrosine (Fig. 2B). 32P-Labeled Abl-phosphorylated p21 migrated as a single band on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 2C, upper left panel) and as two bands on Phos-tag/SDS gels (lower left panel). On Phos-tag/SDS gels, the more abundant of the phosphorylated species (band a) migrated slower than unphosphorylated p21. Phosphorylated Abl did not enter the resolving gel. Unphosphorylated protein detected by Coomassie Blue staining co-migrated with the faster migrating endogenous p21 in YH/J12 cells. Similar results were obtained when Src was used to phosphorylate p21 (data not shown). We concluded that p21 could be tyrosine-phosphorylated in PDGF-transformed glial tumor cells.

FIGURE 2.

p21 is phosphorylated at Tyr-76. A, recombinant His-tagged p21 produced in E. coli and purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-Sepharose was incubated with ATP and Abl or Src kinase as indicated above each lane. Reaction products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes, and the presence of tyrosine-phosphorylated p21 and total p21 (anti-His) was determined by immunoblotting as indicated to the left. B, 293T cells were transfected with Myc-tagged p21 or an empty Myc vector, and the presence of phosphotyrosine in anti-Myc immunoprecipitates (IP) was assessed by immunoblotting. C, the ability of Abl kinase to phosphorylate different mutants of p21 was measured by autoradiography. The upper panel shows the products resolved by conventional SDS-PAGE. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the right. The products were resolved by Phos-tag/SDS-PAGE in the lower panels. 32P-Labeled proteins were detected by fluorography (left panels), and gels were stained with Coomassie Blue (CBB; right panels). The p21 substrates are shown above each lane. Abl was left out of the first lane in each gel. The shifted slower migrating labeled forms of p21 are indicated to the left of the Phos-tag-polyacrylamide gels (a and b). The results of three different experiments were compiled, and the means ± S.E. of the signals are shown in the graphs.

There are two tyrosine residues in p21. Tyr-76, in the 310 helix of the kinase inhibitory domain, and Tyr-146, near the C-terminal proliferating cell nuclear antigen-binding domain. To determine which isoform of p21 is associated with each species detected by Phos-tag/SDS-PAGE, we mutated both of these sites individually and together to phenylalanine, an isomorphic change, and examined the migration of the mutant protein after phosphorylation with Abl. On SDS-polyacrylamide gels, phosphorylation was reduced by 75 ± 2% by the Y76F mutation and by 45 ± 3% by the Y146F mutation (p < 10−4) (Fig. 2C). When resolved by Phos-tag/SDS-PAGE, the mutation of Tyr-76 reduced the a-form by 90% and reduced the amount of the slower migrating b-form by 50%, whereas the Tyr-146 mutation reduced the a-form by 27% and the b-form by 87% (Fig. 2C). Consequently, Tyr-76 is the major contributor to phosphorylation of p21 in PDGF-transformed glial cells.

Tyr-76 Phosphorylation Does Not Affect Cyclin D1-CDK4 Binding

Russo et al. (15) described two binding interfaces between p27 and cyclin A-CDK2. One occurs with the cyclin and another with the CDK. There are three distinct regions of p27 in the CDK interface: a β-hairpin, a β-strand, and the 310 helix. Modeling and biochemical studies indicated that tyrosine phosphorylation in the helix could interfere with interactions with the CDK but not with overall binding, which can still occur through the β-hairpin and β-strand (2, 9–11, 14, 32).

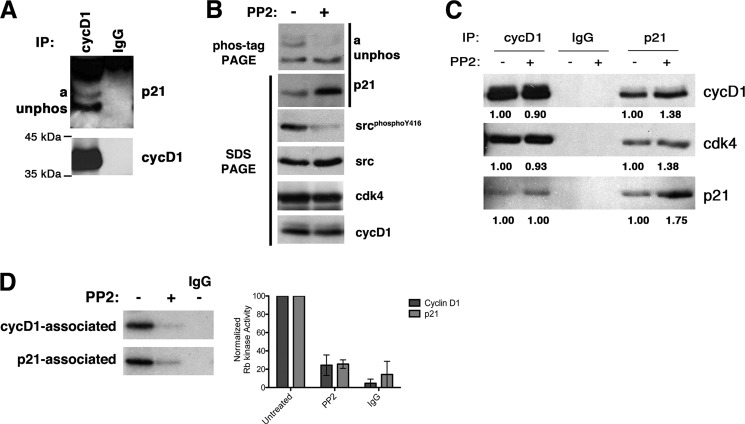

Given the conservation of these domains and tyrosine phosphorylation between p27 and p21 (Fig. 1A), we wanted to determine whether phosphorylation of Tyr-76 affects p21 binding to cyclin-CDK complexes. Consequently, we looked at the association of the different p21 isoforms with cyclin D1 in asynchronously growing YH/J12 cells. Both isoforms of p21 co-precipitated with cyclin D1, and the 1:2 ratio of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated p21 observed in the extracts was observed in the immunoprecipitate (Fig. 3A). This indicates that the phosphorylation state of p21 does not affect binding, consistent with recent studies by Kriwacki and co-workers (33).

FIGURE 3.

Tyrosine phosphorylation does not affect binding to cyclin D1-CDK4 but does reduce inhibitory activity in cells. A, cyclin D1 (cycD1) was immunoprecipitated (IP) from cycling YH/J12 cells. The amount of cyclin D1 was detected by immunoblotting after SDS-PAGE. Molecular mass markers are indicated on the left. The amount of the two isoforms of p21 indicated on the left was determined by immunoblotting after Phos-tag/SDS-PAGE. A control immunoprecipitation with IgG was performed in parallel. B, extracts from PP2-treated and untreated cells (indicated above each lane) were resolved by either Phos-tag/SDS-PAGE or conventional SDS-PAGE and blotted with the antibodies indicated to the right. C, complexes of cyclin D1, CDK4, and p21 were detected by immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting in untreated and PP2-treated cells. The antibodies used for immunoprecipitation are indicated above each pair of lanes, and the antibodies used for immunoblotting are indicated to the right. IgG is a nonspecific antibody raised against rabbit IgG. Band intensities were measured using ImageJ software and are annotated underneath each band. Individual values were normalized to the amount detected in the cyclin D1 immunoprecipitate obtained from untreated cells. D, Rb kinase assay. The presence of Rb kinase activity was measured on cyclin D1 and p21 immunoprecipitates from untreated or PP2-treated cells. Nonspecific IgG was used to mock-immunoprecipitate untreated cells. Quantification from three independent experiments is shown on the right.

Tyr-76 Phosphorylation Correlates with the Activity of a p21-associated Rb Kinase

Tyr-88/Tyr-89 phosphorylation of p27 disrupts the van der Waals and hydrogen bond contacts of the 310 helix, with the CDK allowing p27 to bind with reduced inhibitory activity (9–11). Thus, we tried to specifically reduce the amount of phosphorylated p21 in YH/J12 cells. Treating YH/J12 cells with two receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, PTK787 and STI571, reduced both total p21 and cyclin D1 expression (25). On the other hand, PP2, a Src inhibitor, was able to block the accumulation of phosphorylated p21 and did not affect the expression of cyclin D1 or CDK4 (Fig. 3B). p21 levels even increased in PP2-treated cells (Fig. 3B). We subsequently asked if the association of p21 with cyclin D1 or CDK4 is altered by PP2 treatment. To accomplish this, we quantitated the amount of each protein in cyclin D1 immunoprecipitates from untreated and PP2-treated cells (Fig. 3C). After normalizing the amount of cyclin D1, CDK4, or p21 precipitated with anti-cyclin D1 antibodies in untreated cells, we observed that these proteins were precipitated at equivalent amounts in cyclin D1 immunoprecipitates from treated cells. Similarly, when we immunoprecipitated p21, we observed that the amount of cyclin D1 and CDK4 that co-precipitated was related to the amount of p21. In treated cells, there was an ∼2-fold increase in p21, and we found that both cyclin D1 and CDK4 were increased in the immunoprecipitate. Thus, as expected because both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated isoforms of p21 could bind equally well to cyclin D1-CDK4 (Fig. 3A), the interaction of p21 with cyclin D1 or CDK4 was not significantly affected by PP2 treatment (Fig. 3C). However, both cyclin D1 and p21-associated kinase activities were reduced in PP2-treated cells (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results suggest that the activity of cyclin D1 and p21-associated kinases was related to the accumulation of p21 phosphorylated at Tyr-76.

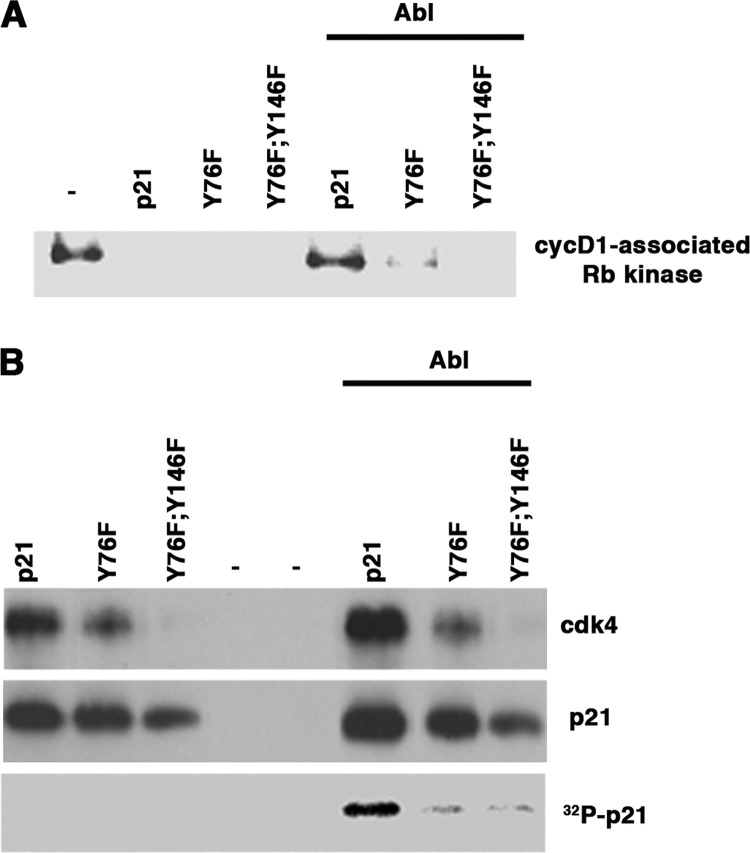

We also asked if tyrosine phosphorylation would reduce cyclin D1-CDK4 inhibitory activity in vitro. To accomplish this, we first phosphorylated p21 with Abl and then incubated the phosphorylated and unphosphorylated proteins with recombinant cyclin D1-CDK4 and measured kinase activity. Rb kinase activity was inhibited by p21, but phosphorylation with the Abl kinase prevented this (Fig. 4A). The Y76F mutant and the Y76F/Y146F double mutant were not phosphorylated (Fig. 4B), and incubation with the Abl kinase did not reduce their inhibitory activities. However, the binding of the double mutant was compromised, suggesting that the Cy2 domain may play a role in stabilizing this complex as well. Thus, in vitro Abl-dependent Tyr-76 phosphorylation reduced p21 inhibitory activity but did not alter its binding to cyclin D1-CDK4 (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Tyrosine phosphorylation does not affect binding to cyclin D1-CDK4 but does reduce inhibitory activity in vitro. A, cyclin D1-associated Rb kinase activity. In the reactions on the right, p21 or the mutants were first incubated with recombinant Abl kinase and then incubated with cyclin D1-CDK4, and Rb kinase activity measured in cyclin D1 immunoprecipitates. Reactions on the left were mock incubated with no Abl kinase. B, the reactions in A were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the amount of CDK4 and p21 was determined by immunoblotting. In parallel reactions that included [γ-32P]ATP, p21 phosphorylation was assessed. Note that there was a reduced association of the double mutant with p21.

Tyr-76 Phosphorylation Is Required for the Growth-promoting Properties of p21

Although it was previously shown (4, 9–12) that tyrosine phosphorylation of p27 correlates with cell growth and that inhibition of this phosphorylation increases its growth inhibitory activity, the significance of this modification to tumor development remained unclear. To test this, a mouse model of tumorigenesis is required. Thus, we used the RCAS-PDGF-HA/nestin-TvA model to examine whether tyrosine modification in the 310 helix of p21 makes a significant contribution to tumor development.

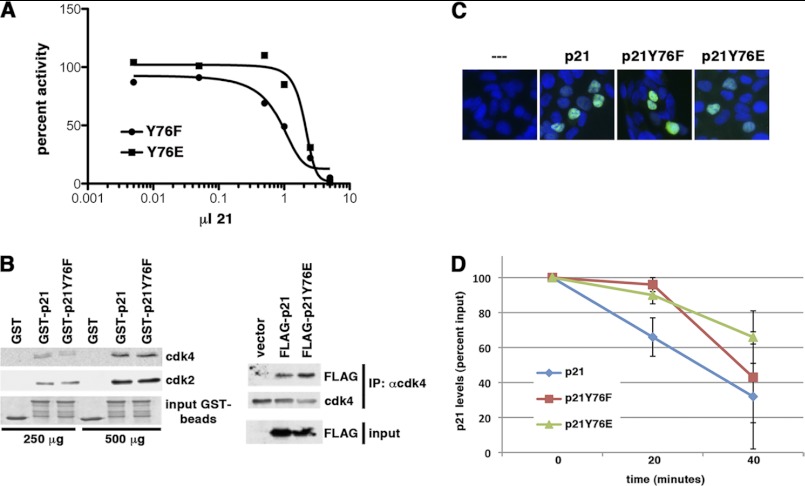

We made two RCAS-PDGF vectors containing alleles of p21, one substituting Tyr-76 with an isomorphic phenylalanine and another with a charged glutamate. Phenylalanine is expected to retain all of the van der Waals and hydrogen bond contacts between the 310 helix and CDK, which are disrupted by phosphorylation. These interactions are only partially disrupted by glutamate (supplemental Fig. 1) (34). The phenylalanine substitution was a more potent inhibitor than the glutamate substitution (Fig. 5A), consistent with the notion that these interactions are necessary for complete inhibition. Residual inhibitory activity in the Y76E mutant might be due to structural distortion of the CDK (2, 33). Neither mutation altered binding of p21 to cyclin-CDK complexes (Fig. 5B), which requires subdomains D1 and LH and the β-hairpin and β-strand of subdomain D2 (14, 33, 35). These mutations did not alter the subcellular localization of the protein (Fig. 5C). However, both mutants were modestly more stable than the wild-type protein (Fig. 5D). Thus, these mutations did not grossly affect the binding of p21 to cyclin-CDK complexes or their localization in the cell, but the Y76F mutant was a stronger inhibitor.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of effects of Y76F and Y76E mutations on inhibitory activity, CDK binding, subcellular localization, and half-life. A, kinase inhibition. The ability of the Y76F and Y76E mutants to inhibit cyclin D1-CDK4 was assessed by Rb kinase assay, and the data from two experiments were averaged after normalizing the input to 100% activity. S.E. of measurement in these assays varied between 10 and 20% depending on the preparation of the inhibitor and cyclin D1-CDK4 complexes. B, p21-CDK4 interaction. Left panel, GST, GST-p21, and GST-p21(Y76F) were prepared from E. coli and bound to glutathione-agarose, and equal amounts of substrate were confirmed on the beads by Coomassie Blue staining (input GST-beads). These beads were then incubated with either 250 or 500 μg of extract prepared from YH/J12 cells, and the amounts of CDK4 and CDK2 associated were then determined by immunoblotting. Right panel, 293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged p21 or FLAG-tagged p21(Y76E), and the amount of p21 was determined in CDK4 immunoprecipitates (IP) by anti-FLAG immunoblotting. The amounts of p21 and p21(Y76E) in the extracts were also determined (input). C, subcellular localization. 3×FLAG-tagged wild-type and mutant p21 as indicated were transfected into 293T cells, and localization was determined by immunofluorescence. Green, anti-Myc antibody; blue, DAPI. D, p21 half-life. 293T cells were transfected with either FLAG-p21 or the Y76F and Y76E mutants as indicated. Cycloheximide was added, and samples were collected over 40 min, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and blotted for anti-FLAG reactivity. Data were compiled from at least three independent experiments with different transfections and then plotted (mean ± S.D.).

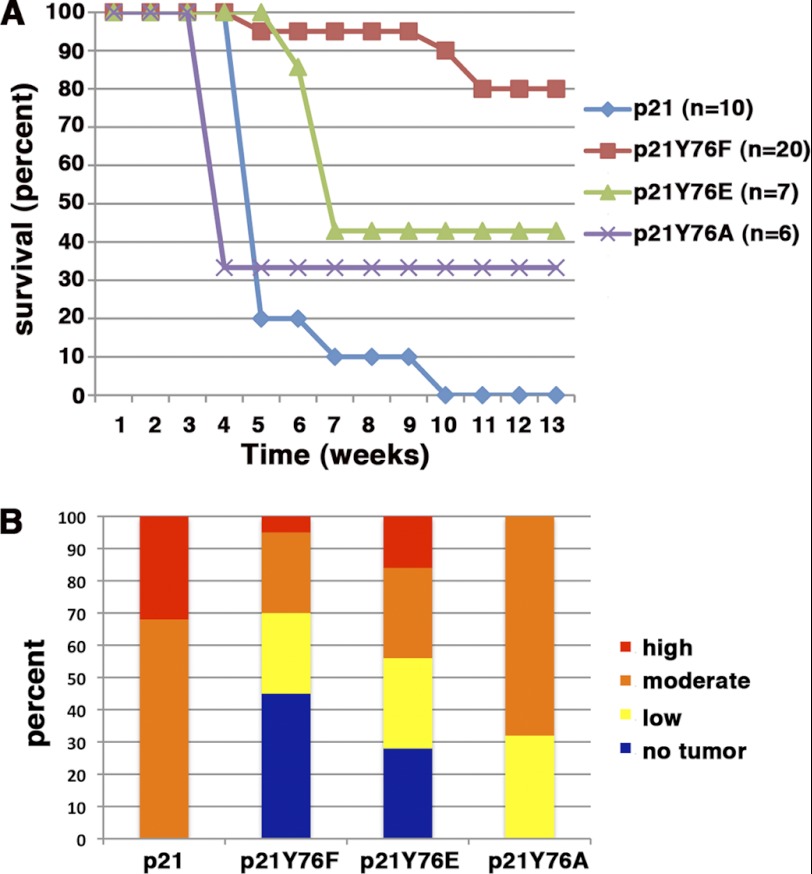

Thus, we introduced RCAS vectors expressing these alleles of p21 into p21-deficient mice and scored these animals for tumor formation and morbidity as originally described (25, 27, 36). p21 knock-out mice are significantly resistant to the tumor-promoting effect of PDGF overexpression, with 95% of the animals tumor-free. The remaining 5% of the mice develop low-grade tumors. 60% of wild-type mice develop moderate- and high-grade tumors, 20% have low-grade tumors, and the rest are tumor-free (25). None of the p21 alleles in the absence of PDGF could induce tumor formation. Reconstitution of p21-deficient mice with wild-type p21 and PDGF resulted in rapid onset of morbidity in all mice (Fig. 6A), and all of the animals developed moderate- to high-grade tumors (Fig. 6B), as we previously described (25). Only 20% of the mice reconstituted with the Y76F mutant and PDGF became morbid. Nevertheless, 55% of the mice developed tumors, but only 30% of these were high or moderate grade. In contrast, 60% of the mice reconstituted with the Y76E mutant and PDGF became morbid, and 75% of the mice had tumors, with 45% of these being moderate to high grade.

FIGURE 6.

Tyr-76 phosphorylation facilitates the progression of PDGF-induced glioma in mice. A, symptom-free survival curve. Wild-type and mutant p21 alleles were introduced into nestin-TvA/p21 knock-out mice with RCAS-PDGF, and animals were monitored for morbidity over 12 weeks. B, tissues from nestin-TvA/p21 knock-out mice reconstituted with the different p21 alleles indicated in A were graded as low (yellow), moderate (orange), or high (red) grade. Animals with no tumors are indicated in blue.

To determine whether the effect of the glutamate substitution is due to alterations in the van der Waals and hydrogen bond contacts between the 310 helix and the CDK rather than a negative charge (37), we also reconstituted a cohort of mice with the Y76A mutant. 70% of these mice became morbid, and all of the mice had tumors, with 70% of these being moderate grade. Consequently, these results demonstrate that phosphorylation at this site facilitates tumor growth by disrupting van der Waals and hydrogen bond contacts between p21 and the catalytic cleft of the CDK.

DISCUSSION

Evidence developed in mouse models of human cancer has unambiguously established that p21 and p27 can contribute in a positive way to promote tumor formation and progression both in a tumor cell-autonomous manner and through effects on the establishment of a suitable tumor microenvironment (for example, see Refs. 25, 27, 36, and 38–42). In tumor cells, a number of possible tumor-promoting mechanisms ranging from proliferation driven by Kip-dependent cyclin D1-CDK4 nuclear localization (25, 39, 41) to an effect on migration and metastasis associated with Kip-dependent interactions with RhoA signaling molecules (36, 38, 40) have been proposed. However, whereas the in vitro cell biological data are consistent with such biochemical hypotheses, and correlative human studies support such interpretations, genetic evidence of the obligatory nature of these interactions and their quantitative effect on tumor development is scarce.

Leveraging the ability to complement genetic deficiencies in tumor cells with different alleles of a gene has allowed us to use the RCAS-PDGF-HA/nestin-TvA model to begin to address the importance of particular modifications and protein interactions in the development of proneural glioma. In this model, we had shown that the CDK inhibitors p27 and p21 did not compensate for each other. p21 facilitates the accumulation of cyclin D1-CDK4 and drives cell proliferation, whereas p27 modulates CDK2-dependent phosphorylation of BRCA2, facilitating formation and resolution of Rad51-dependent repair events. In this work, we have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of the 310 helix of p21 reduces its inhibitory activity toward cyclin D1-CDK4 and that this contributes to tumor progression. Thus, this is the first demonstration that tyrosine phosphorylation of a CDK inhibitor contributes to the progression of tumors from a low-grade to a higher grade malignancy. We suspect that this is shared in other diseases and normal cells that depend on CDK inhibitors to facilitate nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1-CDK4 (43–46).

Such a role facilitating cyclin D1-CDK4 nuclear accumulation has also been proposed for p27 in breast and prostate tumors (39, 41, 47), but there is a notable difference between these models and the glioma model. In the breast and prostate models, tumor development is impaired in both wild-type and knock-out mice compared with heterozygous mice. In contrast, disease in the glioma model is directly related to gene dosage, with knock-out animals developing the fewest tumors and the number increasing in heterozygous mice and increasing further in wild-type animals, ultimately affecting all of the animals when exogenous p21 is provided on an RCAS vector (25). Given the biochemical evidence that the stoichiometry of CDK inhibitors to cyclin-CDK complexes is 1:1 (15, 32, 48) regardless of growth condition, the extensive genetic characterization of different p21 mutants, cyclin D1, and CDK4 in glioma (25, 27, 36), and the observation that tyrosine phosphorylation can alleviate some of the inhibitory activity of p21, the question must arise as to whether non-cyclin D1-CDK4-dependent mechanisms account for the tumor-promoting activity of p27 in those breast and prostate animal models. CDK inhibitors can interact with a number of cytosolic and nuclear proteins, including transcription factors; chromatin-remodeling enzymes; and various molecules involved in cell migration, apoptosis, and cell signaling (49–56). Thus, RCAS-modeling approaches in these organ systems will ultimately allow us to address which biochemical activities are important for tumor development in such models. Furthermore, we suspect that this type of modeling approach can easily be extended to other types of gene products in an economically feasible manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Holland, Jason Huse, and Jim Finney (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for help in preparing and grading the tumors.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA89563 from NCI (to A. K.). This work was also supported by a cancer center core grant from NCI (to the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center), Golfers Against Cancer and Cycle for Survival (to A. K.), a Joel A. Gingras, Jr. American Brain Tumor Association basic research fellowship (to D. C.), and a Geoffrey Beene graduate student fellowship and a Grayer fellowship (to E. H.).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- PDGFR

- PDGF receptor.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. (1995) Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 9, 1149–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blain S. W., Montalvo E., Massagué J. (1997) Differential interaction of the cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitor p27Kip1 with cyclin A-Cdk2 and cyclin D2-Cdk4. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25863–25872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng M., Olivier P., Diehl J. A., Fero M., Roussel M. F., Roberts J. M., Sherr C. J. (1999) The p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 CDK “inhibitors” are essential activators of cyclin D-dependent kinases in murine fibroblasts. EMBO J. 18, 1571–1583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kardinal C., Dangers M., Kardinal A., Koch A., Brandt D. T., Tamura T., Welte K. (2006) Tyrosine phosphorylation modulates binding preference to cyclin-dependent kinases and subcellular localization of p27Kip1 in the acute promyelocytic leukemia cell line NB4. Blood 107, 1133–1140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. LaBaer J., Garrett M. D., Stevenson L. F., Slingerland J. M., Sandhu C., Chou H. S., Fattaey A., Harlow E. (1997) New functional activities for the p21 family of CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 11, 847–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sherr C. J., Roberts J. M. (1999) CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 13, 1501–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soos T. J., Kiyokawa H., Yan J. S., Rubin M. S., Giordano A., DeBlasio A., Bottega S., Wong B., Mendelsohn J., Koff A. (1996) Formation of p27-CDK complexes during the human mitotic cell cycle. Cell Growth Differ. 7, 135–146 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weiss R. H., Joo A., Randour C. (2000) p21Waf1/Cip1 is an assembly factor required for platelet-derived growth factor-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10285–10290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chu I., Sun J., Arnaout A., Kahn H., Hanna W., Narod S., Sun P., Tan C. K., Hengst L., Slingerland J. (2007) p27 phosphorylation by Src regulates inhibition of cyclin E-Cdk2. Cell 128, 281–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grimmler M., Wang Y., Mund T., Cilensek Z., Keidel E. M., Waddell M. B., Jäkel H., Kullmann M., Kriwacki R. W., Hengst L. (2007) Cdk inhibitory activity and stability of p27Kip1 are directly regulated by oncogenic tyrosine kinases. Cell 128, 269–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. James M. K., Ray A., Leznova D., Blain S. W. (2008) Differential modification of p27Kip1 controls its cyclin D-Cdk4 inhibitory activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 498–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larrea M. D., Liang J., Da Silva T., Hong F., Shao S. H., Han K., Dumont D., Slingerland J. M. (2008) Phosphorylation of p27Kip1 regulates assembly and activation of cyclin D1-Cdk4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6462–6472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lacy E. R., Filippov I., Lewis W. S., Otieno S., Xiao L., Weiss S., Hengst L., Kriwacki R. W. (2004) p27 binds cyclin-CDK complexes through a sequential mechanism involving binding-induced protein folding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 358–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ou L., Ferreira A. M., Otieno S., Xiao L., Bashford D., Kriwacki R. W. (2011) Incomplete folding upon binding mediates Cdk4-cyclin D complex activation by tyrosine phosphorylation of inhibitor p27 protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 30142–30151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Russo A. A., Jeffrey P. D., Patten A. K., Massagué J., Pavletich N. P. (1996) Crystal structure of the p27Kip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor bound to the cyclin A-Cdk2 complex. Nature 382, 325–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alt J. R., Gladden A. B., Diehl J. A. (2002) p21Cip1 promotes cyclin D1 nuclear accumulation via direct inhibition of nuclear export. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8517–8523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landis M. W., Pawlyk B. S., Li T., Sicinski P., Hinds P. W. (2006) Cyclin D1-dependent kinase activity in murine development and mammary tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 9, 13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Doetsch F. (2003) The glial identity of neural stem cells. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1127–1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fisher G. H., Orsulic S., Holland E., Hively W. P., Li Y., Lewis B. C., Williams B. O., Varmus H. E. (1999) Development of a flexible and specific gene delivery system for production of murine tumor models. Oncogene 18, 5253–5260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Holland E. C. (2001) Gliomagenesis: genetic alterations and mouse models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 120–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brennan C., Momota H., Hambardzumyan D., Ozawa T., Tandon A., Pedraza A., Holland E. (2009) Glioblastoma subclasses can be defined by activity among signal transduction pathways and associated genomic alterations. PLoS ONE 4, e7752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Phillips H. S., Kharbanda S., Chen R., Forrest W. F., Soriano R. H., Wu T. D., Misra A., Nigro J. M., Colman H., Soroceanu L., Williams P. M., Modrusan Z., Feuerstein B. G., Aldape K. (2006) Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell 9, 157–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robinson S., Cohen M., Prayson R., Ransohoff R. M., Tabrizi N., Miller R. H. (2001) Constitutive expression of growth-related oncogene and its receptor in oligodendrogliomas. Neurosurgery 48, 864–873; discussion 873–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salpietro M., Holland E. C. (2005) Modeling and preclinical trials for gliomas. Clin. Neurosurg. 52, 104–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu Y., Yeh N., Zhu X. H., Leversha M., Cordon-Cardo C., Ghossein R., Singh B., Holland E., Koff A. (2007) Somatic cell type-specific gene transfer reveals a tumor-promoting function for p21Waf1/Cip1. EMBO J. 26, 4683–4693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soos T. J., Park M., Kiyokawa H., Koff A. (1998) Regulation of the cell cycle by CDK inhibitors. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 22, 111–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ciznadija D., Liu Y., Pyonteck S. M., Holland E. C., Koff A. (2011) Cyclin D1 and Cdk4 mediate development of neurologically destructive oligodendroglioma. Cancer Res. 71, 6174–6183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. See W. L., Miller J. P., Squatrito M., Holland E., Resh M. D., Koff A. (2010) Defective DNA double-strand break repair underlies enhanced tumorigenesis and chromosomal instability in p27-deficient mice with growth factor-induced oligodendrogliomas. Oncogene 29, 1720–1731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dai C., Celestino J. C., Okada Y., Louis D. N., Fuller G. N., Holland E. C. (2001) PDGF autocrine stimulation dedifferentiates cultured astrocytes and induces oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas from neural progenitors and astrocytes in vivo. Genes Dev. 15, 1913–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ligon K. L., Huillard E., Mehta S., Kesari S., Liu H., Alberta J. A., Bachoo R. M., Kane M., Louis D. N., Depinho R. A., Anderson D. J., Stiles C. D., Rowitch D. H. (2007) Olig2-regulated lineage-restricted pathway controls replication competence in neural stem cells and malignant glioma. Neuron 53, 503–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Verhaak R. G., Hoadley K. A., Purdom E., Wang V., Qi Y., Wilkerson M. D., Miller C. R., Ding L., Golub T., Mesirov J. P., Alexe G., Lawrence M., O'Kelly M., Tamayo P., Weir B. A., Gabriel S., Winckler W., Gupta S., Jakkula L., Feiler H. S., Hodgson J. G., James C. D., Sarkaria J. N., Brennan C., Kahn A., Spellman P. T., Wilson R. K., Speed T. P., Gray J. W., Meyerson M., Getz G., Perou C. M., Hayes D. N. (2010) Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 17, 98–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lacy E. R., Wang Y., Post J., Nourse A., Webb W., Mapelli M., Musacchio A., Siuzdak G., Kriwacki R. W. (2005) Molecular basis for the specificity of p27 toward cyclin-dependent kinases that regulate cell division. J. Mol. Biol. 349, 764–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y., Fisher J. C., Mathew R., Ou L., Otieno S., Sublet J., Xiao L., Chen J., Roussel M. F., Kriwacki R. W. (2011) Intrinsic disorder mediates the diverse regulatory functions of the Cdk inhibitor p21. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 214–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tüdös E., Cserzö M., Simon I. (1990) Predicting isomorphic residue replacements for protein design. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 36, 236–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hashimoto Y., Kohri K., Kaneko Y., Morisaki H., Kato T., Ikeda K., Nakanishi M. (1998) Critical role for the 310 helix region of p57Kip2 in cyclin-dependent kinase 2 inhibition and growth suppression. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 16544–16550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. See W. L., Heinberg A. R., Holland E. C., Resh M. D. (2010) p27 deficiency is associated with migration defects in PDGF-expressing gliomas in vivo. Cell Cycle 9, 1562–1567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anthis N. J., Haling J. R., Oxley C. L., Memo M., Wegener K. L., Lim C. J., Ginsberg M. H., Campbell I. D. (2009) β integrin tyrosine phosphorylation is a conserved mechanism for regulating talin-induced integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 36700–36710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Besson A., Hwang H. C., Cicero S., Donovan S. L., Gurian-West M., Johnson D., Clurman B. E., Dyer M. A., Roberts J. M. (2007) Discovery of an oncogenic activity in p27Kip1 that causes stem cell expansion and a multiple tumor phenotype. Genes Dev. 21, 1731–1746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gao H., Ouyang X., Banach-Petrosky W., Borowsky A. D., Lin Y., Kim M., Lee H., Shih W. J., Cardiff R. D., Shen M. M., Abate-Shen C. (2004) A critical role for p27kip1 gene dosage in a mouse model of prostate carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17204–17209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee S., Helfman D. M. (2004) Cytoplasmic p21Cip1 is involved in Ras-induced inhibition of the ROCK/LIMK/cofilin pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1885–1891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Muraoka R. S., Lenferink A. E., Law B., Hamilton E., Brantley D. M., Roebuck L. R., Arteaga C. L. (2002) ErbB2/Neu-induced, cyclin D1-dependent transformation is accelerated in p27-haploinsufficient mammary epithelial cells but impaired in p27-null cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 2204–2219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vidal A., Zacharoulis S., Guo W., Shaffer D., Giancotti F., Bramley A. H., de la Hoz C., Jensen K. K., Kato D., MacDonald D. D., Knowles J., Yeh N., Frohman L. A., Rafii S., Lyden D., Koff A. (2005) p130Rb2 and p27Kip1 cooperate to control mobilization of angiogenic progenitors from the bone marrow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6890–6895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bansal R., Marin-Husstege M., Bryant M., Casaccia-Bonnefil P. (2005) S-phase entry of oligodendrocyte lineage cells is associated with increased levels of p21Cip1. J. Neurosci. Res. 80, 360–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dong Y., Chi S. L., Borowsky A. D., Fan Y., Weiss R. H. (2004) Cytosolic p21Waf1/Cip1 increases cell cycle transit in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell. Signal. 16, 263–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jäkel H., Weinl C., Hengst L. (2011) Phosphorylation of p27Kip1 by JAK2 directly links cytokine receptor signaling to cell cycle control. Oncogene 30, 3502–3512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kavurma M. M., Khachigian L. M. (2004) Vascular smooth muscle cell-specific regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/Cip1 transcription by Sp1 is mediated via distinct cis-acting positive and negative regulatory elements in the proximal p21WAF1/Cip1 promoter. J. Cell. Biochem. 93, 904–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jones J. M., Cui X. S., Medina D., Donehower L. A. (1999) Heterozygosity of p21WAF1/CIP1 enhances tumor cell proliferation and cyclin D1-associated kinase activity in a murine mammary cancer model. Cell Growth Differ. 10, 213–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hengst L., Göpfert U., Lashuel H. A., Reed S. I. (1998) Complete inhibition of Cdk/cyclin by one molecule of p21Cip1. Genes Dev. 12, 3882–3888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Abbas T., Dutta A. (2009) p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 400–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Blagosklonny M. V. (2002) Are p27 and p21 cytoplasmic oncoproteins? Cell Cycle 1, 391–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coqueret O. (2003) New roles for p21 and p27 cell cycle inhibitors: a function for each cell compartment? Trends Cell Biol. 13, 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Denicourt C., Dowdy S. F. (2004) Cip/Kip proteins: more than just CDK inhibitors. Genes Dev. 18, 851–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gartel A. L., Tyner A. L. (2002) The role of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in apoptosis. Mol. Cancer Ther. 1, 639–649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Moeller S. J., Head E. D., Sheaff R. J. (2003) p27Kip1 inhibition of GRB2-SOS formation can regulate Ras activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3735–3752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Perkins N. D. (2002) Not just a CDK inhibitor: regulation of transcription by p21WAF1/CIP1/SDI1. Cell Cycle 1, 39–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shim J., Lee H., Park J., Kim H., Choi E. J. (1996) A non-enzymatic p21 protein inhibitor of stress-activated protein kinases. Nature 381, 804–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]