Background: Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) is the causative agent of Johne and Crohn diseases.

Results: CobT contributes to the development of T cell immunity through the activation of dendritic cells (DC).

Conclusion: CobT is a novel DC maturation-inducing antigen that drives Th1 polarized-naive/memory T cell expansion.

Significance: CobT can be an important candidate for the development of vaccine and a IFN-γ-based diagnostic tool.

Keywords: Dendritic Cells, Immunology, Mycobacteria, T Cell, Toll-like Receptors (TLR), Memory T Cell, Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis, Th1 Polarization, Toll-like Receptor 4

Abstract

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) is the causative agent of Johne disease in animals and MAP involvement in human Crohn disease has been recently emphasized. Evidence from M. tuberculosis studies suggests mycobacterial proteins activate dendritic cells (DCs) via Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4, eventually determining the fate of immune responses. Here, we investigated whether MAP CobT contributes to the development of T cell immunity through the activation of DCs. MAP CobT recognizes TLR4, and induces DC maturation and activation via the MyD88 and TRIF signaling cascades, which are followed by MAP kinases and NF-κB. We further found that MAP CobT-treated DCs activated naive T cells, effectively polarized CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and IL-2, but not IL-4 and IL-10, and induced T cell proliferation. These data indicate that MAP CobT contributes to T helper (Th) 1 polarization of the immune response. MAP CobT-treated DCs specifically induced the expansion of CD4+/CD8+CD44highCD62Llow memory T cells in the mesenteric lymph node of MAP-infected mice in a TLR4-dependent manner. Our results indicate that MAP CobT is a novel DC maturation-inducing antigen that drives Th1 polarized-naive/memory T cell expansion in a TLR4-dependent cascade, suggesting that MAP CobT potentially links innate and adaptive immunity against MAP.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs)3 are potent antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that play a pivotal role in determining the fate of the immune response to a variety of pathogens (1). Immature dendritic cells exist in peripheral tissues where they efficiently capture antigens using pattern recognition receptors (2). Among these pattern recognition receptors, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play important roles in innate immunity by their recognition of conserved molecular structures produced by microorganisms (3). Upon recognition of specific microbial components, these TLRs recruit several adaptor molecules, including myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) and Toll/IL-1R domain-containing adaptor (TRIF), and ultimately induce NF-κB nuclear translocation to initiate immune responses (3). During this process, DCs mature and relocate to the lymph nodes, where they activate naive T cells to initiate adaptive immune responses by stimulating antigenic peptide-presenting major histocompatability complex (MHC) I and II molecules and co-stimulatory molecules, such as CD80 and CD86 (1). Previously, it was reported that DCs infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis (MAP) up-regulate maturation markers, including CD80, CD86, and CD40, migrate toward mesenteric lymph nodes, and thus interact with T cells in lymph nodes (4). As mentioned, DC maturation is a key control point in the shift from innate to adaptive immunity induced by pathogens.

MAP, as a member of the Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), is the causative agent of Johne disease, which is characterized by contagious, chronic granulomatous enteritis (5). Unlike other MAC members, MAP cannot proliferate in the environment but is spread through fecal shedding by animals exposed to MAP. MAP has long been suspected as the causative agent in Crohn disease (CD) in humans, although this interrelationship is still controversial. CD is an inflammatory bowel disease that may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in a wide variety of symptoms, including weight loss, diarrhea, or vomiting (6).

Recently, cell-mediated immune reactions of MAP-secreted antigens have been evaluated for vaccine development or more effective therapies in defense against MAP infection (7–11). For example, a MAP fibronectin attachment protein induces DC maturation and activation, which drives T helper (Th) 1 polarization (7). Moreover, the 70-kDa heat-shock protein of MAP has been reported to strongly induce DC maturation and activation by regulating the NF-κB and MAPK pathways and enhancing the ability of DCs to stimulate CD4+ T cells, ultimately resulting in increased protective immune responses against MAP (8, 9). It has been shown that MAP Ag85 is the immunodominant T cell antigen in MAP infection, inducing strong proliferation and interferon γ (IFN-γ) (10). The 35-kDa protein of MAP has been reported to elicit host cell-mediated immune reaction in a mouse model, as represented by proliferation and IFN-γ production (11). In this regard, antigens capable of activating DCs toward the Th1 type of immune response offer attractive vaccine potential. Unfortunately, the majority of antigens are poor immunogens because they fail to initiate a productive T cell response. Given this information, identification and characterization of MAP antigens that are potent modulators of host immune responses to pathogens is critical for the development of better early diagnostic reagents and an effective MAP vaccine.

DCs provide an important link between innate and adaptive immunity against pathogens and are essential for eliciting protective immunity to infectious agents, including pathogenic mycobacteria (12). This protective immunity is also executed by initiating adaptive immunity, including CD4+ T helper (Th) type 1 cell-mediated immunity through DC activation (13). In addition, polarization of Th1 responses plays a critical role in the eradication of pathogens through IFN-γ production that activates innate cell-mediated immunity (14). Furthermore, antigen-specific memory T cells are key mediators of protective immune responses because of their increased frequency and enhanced reactivity after restimulation (15). Thus, the generation and proliferation of antigen-specific memory T cells is essential for rapid clearance and neutralization of pathogens encountered during a prior infection (15). Based on these circumstances, activation of Th1 cell-mediated immune responses and memory T cell formation by mycobacterial antigens are critically important for the generation of protective immune responses against pathogens. In this study, we investigated the function and precise mechanism of MAP CobT in DC activation, and its role as a link between innate and adaptive immune responses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Specific pathogen-free female C57BL/6 (H-2Kb and I-Ab), BALB/c (H-2Kd and I-Ad), C57BL/6J TLR2 knock-out mice (TLR2−/−; B6.129-Tlr2tm1Kir/J), C57BL/10 TLR4 knock-out mice (TLR4−/−; C57BL/10ScNJ), and C57BL/6 OT-1 and OT-2 T cell receptor transgenic mice (aged 5–6 weeks) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained under barrier conditions in a biohazard animal room at the Medical Research Center, Chungnam National University. The animals were fed a sterile commercial mouse diet and provided with water ad libitum. All animal experiments complied with the ethical and experiment regulations for animal care at Chungnam National University.

Animal infection studies were performed in a BL-2 biohazard animal facility at the Medical Research Center, Chungnam National University. Briefly, 6-week-old BALB/c mice were infected via intravenous injection with 106 CFU/0.2 ml/mouse of MAP K-10 strain (7). Bacteria were counted 1 day after infection and ∼300 viable MAP were delivered to the intestines. Five to six mice were euthanized at 4 and 10 weeks post-infection and intestines were collected for subsequent experiments, including mixed lymphocyte reactions. All infection-related experiments were done according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations, Medical Research Center, Chungnam National University.

Antibodies and Reagents

Recombinant mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin-4 (IL-4), and the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-annexin V/propidium iodide kit were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Dextran-FITC (molecular mass, 40,000 Da) was obtained from Sigma. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli O111:B4 was purchased from Sigma. An endotoxin filter (END-X) and an endotoxin removal resin (END-X B15) were acquired from Associates of Cape Cod (East Falmouth, MA). Peptron synthesized the OT-I peptide (OVA(257–264)) and OT-II peptide (OVA(323–339)). A summary of the source, name, description, and origin for antibodies used in this study is listed in supplemental Table S1.

Generation and Culture of Murine Bone Marrow-derived DCs

Bone marrow cells isolated from C57BL/6 mice were lysed with red blood cell (RBC) lysing buffer (ammonium chloride 4.15 g/500 ml, 0.01 m Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5, ±2) and washed with RPMI 1640 media. The obtained cells were plated in six-well culture plates (106 cells/ml, 3 ml/well) and cultured at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 using RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 100 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza), 50 μm mercaptoethanol (Lonza), 0.1 mm nonessential amino acid (Lonza), 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Sigma), 20 ng/ml of GM-CSF, and 20 ng/ml of IL-4. On days 6 or 7 of culture, nonadherent cells and loosely adherent proliferating DCs aggregates were harvested for analysis or stimulation, or in some experiments they were replated into 60-mm dishes (106 cells/ml, 5 ml/dish). On day 6, over 80% of the nonadherent cells expressed CD11c. To obtain highly purified populations for subsequent analyses, the DCs were labeled with bead-conjugated anti-CD11c mAb (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), followed by positive selection on paramagnetic columns (LS columns, Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The purity of the cell fraction selected was >95%.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant MAP CobT

The MAP cobT gene was PCR amplified from MAP genomic DNA using the following primers: forward, 5′-CATATGGAATTCGCGACCGTCTCGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCGAGCGGGTGAGCGGACGGGTCG-3′. The MAP cobT product was digested with NdeI and XhoI, and the insert was ligated into a pET22b(+) vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) and digested with the same enzymes. Overexpressed MAP CobT was prepared with a slight modification after cell disruption by sonication and nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin purification, as previously described (16). To remove endotoxins from the purified protein, the dialyzed recombinant protein was incubated for 6 h at 4 °C with polymyxin B (PmB)-agarose (Sigma). Purified endotoxin-free MAP CobT was filter sterilized and stored at −70 °C. The protein concentration was estimated using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce). Residual LPS in the MAP CobT preparation was determined using the Limulus amoebocyte lysate (LAL) test (Lonza), according to the manufacturer's instructions. MAP CobT purity was evaluated by Coomassie Blue staining and Western blot using a histidine antibody.

Cytotoxicity Analyses

To investigate the cytotoxic effect of MAP CobT on DCs, the cell death pattern of DCs in 12-well plates (0.5 × 106 cells/ml) was analyzed after treatment with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT as recently described (17).

Cytokine Measurements

A sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-2, IL-12p70, and IL-10 in culture supernatants as described previously (17).

Intracellular Cytokine Assays

Intracellular cytokine assays was carried out as previously described (17). Intracellular IL-12p70, IL-10, IL-2, IL-4, and IFN-γ were detected with fluorescein-conjugated antibodies (BD Biosciences) in a permeation buffer. The cells were analyzed by flow cytometry using the CellQuest (BD Biosciences) program.

Surface Molecule Expression Analyses by Flow Cytometry

Cell surface staining was performed with specifically labeled fluorescein-conjugated monoclonal antibodies. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry and data were analyzed using CellQuest data analysis software.

Antigen Uptake Ability of DCs by MAP CobT

DCs (2 × 105 cells) were equilibrated at 37 or 4 °C for 45 min and pulsed with 1 mg/ml of fluorescein-conjugated dextran. Cold staining buffer was added to stop the reaction. Cells were washed three times, stained with PE-conjugated CD11c antibodies, and analyzed with FACSCanto. Nonspecific dextran binding to DCs was determined by incubating DCs with FITC-conjugated dextran at 4 °C. The resulting background value was subtracted from the specific binding values.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy

DCs were plated overnight on poly-l-lysine-coated glass coverslips. After treatment with MAP CobT, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton X-100, and then blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS/T) for 2 h before being incubated with 2% BSA in PBS/T containing anti-His antibody for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with PBS/T, the cells were reincubated with Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody in a dark room for 1 h, and then were stained with 1 μg/ml of DAPI for 10 min at room temperature. Cell morphology and fluorescence intensity were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM510 Meta; Carl Zeiss Ltd., Welwyn Garden City, UK). Images were acquired using LSM510 Meta software and processed using the LSM image examiner.

Immunoprecipitation

DCs (1 × 107 cells) were incubated for 6 h with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT and cell pellets were lysed with lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm PMSF, 1 μg/ml each aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm NaF). Total cell lysates were precleared with protein A- or G-Sepharose for 2 h at 4 °C. The bead/cell lysate mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C and the supernatant was collected for subsequent experiments. After incubation for 1 h at 4 °C with anti-rat IgG as control antibody for anti-TLR2 and -TLR4 or anti-mouse IgG as control antibody for anti-MAP CobT (His), MAP CobT (His), TLR2, and TLR4-associated proteins were immunoprecipitated by incubation for 24 h at 4 °C with protein A- or G-Sepharose. Beads were harvested, washed, and boiled in 5× sample buffer for 5 min. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were further probed with the TLR2, TLR4, or His antibodies as indicated.

Immunoblotting Analyses

After stimulation with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT, DCs were lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, 50 mm NaF, 30 mm Na4PO7, 1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 2 μg/ml of aprotinin, and 1 mm pervanadate. Whole cell lysate samples were resolved on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5% skim milk and incubated with the antibody for 2 h, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary Abs for 1 h at room temperature. Target protein epitopes, including MAPKs, NF-κB, T-bet, and GATA-3, specifically recognized by antibodies were visualized using the ECL Advance Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare).

Nuclear Extract Preparation

DCs were treated with 100 μl of lysis buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm PMSF) on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 5 min, the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of extraction buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 400 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF) and incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant containing nuclear extracts was collected.

Mixed Lymphocyte Reaction

Responder T cells, which participate in naive T cell reactions, were isolated using a magnetic-activated cell sorting column (Miltenyi Biotec) from total mononuclear cells prepared from BALB/c mice. Both OVA-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responders were obtained from splenocytes of OT-1 and OT-2 mice, respectively. These T cells were stained with 1 μm carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Invitrogen) as previously described (17). DCs (2 × 105 cells per well) treated with OVA peptide in the presence of MAP CobT for 24 h were co-cultured with CFSE-stained CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (2 × 106) at DC:T cell ratios of 1:10. On days 3 or 4 of the co-culture, each T cell was stained with PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated anti-CD4+ mAb, PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD4+ mAb, PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD8+ mAb, Alexa 647-conjugated anti-CCR3 mAb, or PE-conjugated anti-CXCR3 mAb and analyzed by flow cytometer. The supernatants were harvested and measured the production of IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 by ELISA.

Analysis of the Activation of Effector/Memory T Cells

As explained above, responder T cells, which participate in allogeneic T cell reactions, were isolated using a magnetic-activated cell sorting column (Miltenyi Biotec) from total mononuclear cells prepared from MAP-infected BALB/c mice. Staining with the APC-conjugated CD3 monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences) revealed that the preparation consisted mainly of CD3+ cells (>95%). DCs (2 × 105 cells per well) prepared from wild-type (WT), TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− C57BL/6 mice were treated with MAP CobT for 24 h, extensively washed, and co-cultured with 2 × 106 responder allogeneic MLN (MAP-infected T cells) at a DC:T cell ratio of 1:10. On day 4 of co-culture, cells were stained with PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated CD4+, PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated CD8+, Alexa 488-conjugated CD62L, and PE-conjugated CD44 monoclonal antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. T-bet and GATA-3 expression in T cells from Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected mice was assessed by immunoblotting using specific T-bet and GATA-3 monoclonal antibodies.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Nuclear extracts for EMSA were prepared from DCs as described previously (18) with minor modification. Briefly, 5 μg of nuclear extract was incubated at room temperature for 20 min with reaction buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.9, 50 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 5% glycerol, 200 μg/ml of BSA, and 2 μg of poly(dI-dC)). Then the 32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide (1 ng, ≥1 × 105 cpm) containing the NF-κB binding consensus sequence (5′-GGCAACTGGGGACTCTCCCTTT-3′) was added to the reaction mixture for an additional 10 min at room temperature. The reaction products were fractionated on a nondenaturating 6% polyacrylamide gel, which was then dried and subjected to autoradiography. For characterization of κB-binding proteins, the reactions were supplemented with affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies against p50, p65, or p52 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), 30 min before electrophoresis.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assays

DCs were treated with CobT for 0, 30, and 60 min. Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde. ChIP assays and PCR were performed using commercially available kit (Active motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol using 2 μg of anti-NF-κB p65 antibody-ChIP grade (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). An aliquot of the cell lysates was used to isolate total input DNA. In some experiments IgG was used a negative control. Input DNA samples as well as antibody-enriched ChIP DNA samples were analyzed by regular PCR using the following set of primers from a region of the mouse Tnf-α (forward, 5′-TGAGTTGATGTACCGCAGTCAAGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGAGCAGCTTGAGAGTTGGGAAGT-3′ and Il-6 (forward, 5′-CGATGCTAAACGACGTCACATTGTGCA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTCCAGAGCAGAATGAGCTACAGACAT-3′) promoters around the NF-κB binding sites. A 5-μl DNA extract was used for PCR. Confirmation of LPS-decontamination for MAP CobT, pharmacological inhibitor treatment, and transfection details of these methods can be found in the supplemental methods.

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were repeated at least three times with consistent results. The levels of significance for comparison between samples were determined by Tukey's multiple comparison test distribution using statistical software (GraphPad Prism Software, version 4.03; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are expressed as the mean ± S.E.

RESULTS

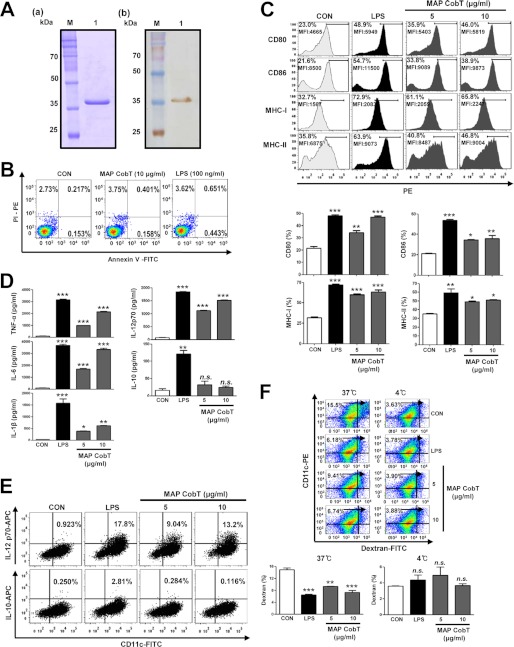

Purification and Cytotoxicity of Recombinant MAP CobT

Recombinant MAP CobT was extracted as described and purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin. After dialysis, endotoxin-contaminated MAP CobT was removed, as confirmed by SDS-PAGE. The purified MAP CobT protein had a molecular mass of ∼35.2 kDa as assessed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). Endotoxin content was measured by LAL assay and was <15 pg/ml (<0.1 EU/ml). MAP CobT had 96% purity when 20 μg of the protein preparation was stained with silver nitrate (data not shown). Next, we examined MAP CobT protein-induced cytotoxicity in DCs. Cells were treated for 24 h with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT protein and stained with CD11c, annexin V, and PI to assess cell viability. MAP CobT was not toxic against DCs (Fig. 1B), suggesting that recombinant MAP CobT is not cytotoxic when used at concentrations below 10 μg/ml.

FIGURE 1.

MAP CobT induces phenotypical and functional maturation of DCs. A, recombinant MAP CobT was produced in BL21 cells and purified with NTA resin. The purified protein was then subjected to (a) SDS-PAGE and (b) Western blot analyses using 1:1000 mouse anti-His antibodies. B, DCs were treated for 24 h with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT and 100 ng/ml of LPS. DCs were stained with annexin V-FITC/PI-PE and analyzed by flow cytometry. C, DCs were stimulated for 24 h with 100 ng/ml of LPS, or 5 or 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT, and analyzed for surface marker expression by two-color flow cytometry. Cells were gated to include CD11c+ cells. DCs were stained with anti-CD80, anti-CD86, or anti-MHC class I or anti-MHC class II. The percentage of positive cells is shown for each panel. Bar graphs show the mean ± S.E. of the percentages of each surface molecule on CD11c+ cells for three independent experiments. Statistical significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001) of treatments compared with controls is indicated. D, DCs were stimulated for 24 h with 100 ng/ml of LPS, or 5 or 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT, and the amounts of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-12p70 in the culture supernatant were measured by ELISA. All data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Statistical significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001) is shown for treatments compared with the controls. E, dot plots of intracellular IL-12p70 and IL-10 in CD11c+ DCs. The percentage of positive cells is shown in each panel. F, endocytic activity of MAP CobT-treated versus untreated DCs. Endocytic activity at 37 or 4 °C was assessed by flow cytometry analyses as dextran-FITC uptake. The percentages of dextran-FITC+CD11c+ cells are indicated. Bar graphs show the mean ± S.E. of the percentage of dextran-FITC+CD11c+ cells for three independent experiments. Statistical significance (**, p < 0.01 or ***, p < 0.001) is indicated for treatments compared with controls.

MAP CobT Induces DC Maturation and Th1 Polarization

To investigate whether MAP CobT affects DC maturation, DCs were incubated for 24 h with 5 and 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT. LPS was used as a positive control for DC maturation. DC surface molecule expression, including CD80, CD86, and MHC class I and II, was analyzed by flow cytometry. MAP CobT enhanced expression of these surface molecules at both concentrations (Fig. 1C).

We next analyzed whether MAP CobT-mediated DC maturation was associated with pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokine secretion by stimulating DCs with various concentrations of MAP CobT (5–10 μg/ml). As demonstrated in Fig. 1D, MAP CobT induced DCs to secrete high levels of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β. In addition, MAP CobT significantly induced IL-12p70 secretion, but not IL-10 (Fig. 1D). We also analyzed production of intracellular IL-12p70 and IL-10 in MAP CobT-treated DCs. DCs treated with MAP CobT showed increased IL-12p70-positive cells compared with untreated DCs, whereas the expression of IL-10-positive cells was not observed (Fig. 1E).

We also investigated whether MAP CobT regulates DC endocytic activity. MAP CobT treatment significantly decreased the percentage of dextran+CD11c+ cells (Fig. 1F) compared with untreated DCs. These results strongly suggest that MAP CobT induces the functional maturation of DCs and MAP CobT-matured DCs may promote a Th1 type immune response.

Purified MAP CobT Does Not Have LPS Contamination

To ensure that MAP CobT-induced DC maturation was not due to endotoxin or LPS contamination, the purified MAP CobT preparations were passed through a polymyxin B-agarose column. Furthermore, we assessed LPS contamination by treatment with proteinase K or heat denaturation, which abrogated the ability of MAP CobT to trigger DC maturation (supplemental Fig. 1, A and B). Polymyxin B treatment did not affect MAP CobT viability, whereas polymyxin B significantly inhibited LPS (supplemental Fig. 1C). These results confirmed that DC maturation was induced by intact MAP CobT and not by contaminating LPS.

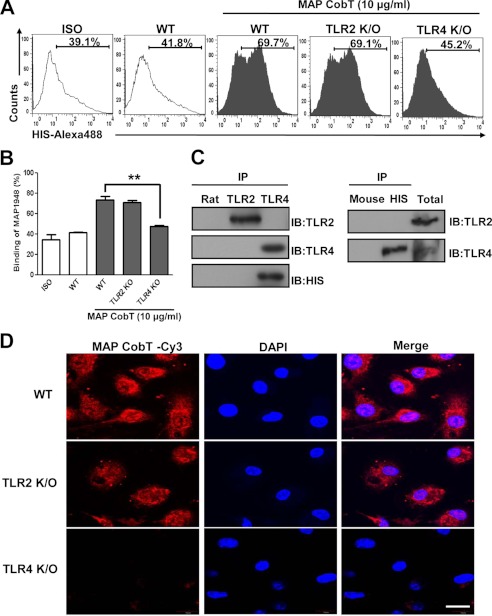

MAP CobT Interacts with TLR4 and Induces DC Maturation

Pattern recognition receptors, such as TLRs, recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns from whole mycobacterial cells or mycobacterial cell wall components (19). Thus, we examined whether MAP CobT is recognized by, and acts through, TLRs in DCs. To identify TLRs on DCs that interact with MAP CobT, wild-type (WT), TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− DCs were stimulated with MAP CobT. Surface expression of MAP was detected with an Alexa 488-conjugated MAP CobT polyclonal antibody (Fig. 2A). The MAP CobT antibody bound to the cell surface of WT and TLR4−/− DCs but not TLR2−/− DCs (Fig. 2B). To confirm the interaction between MAP CobT and TLR, we performed immunoprecipitation studies and determined that MAP CobT bound TLR4 but not TLR2 (Fig. 2C). This observation was also confirmed by confocal microscopy. We also found that MAP CobT preferentially interacts with WT and TLR2−/− DCs, not TLR4−/− DCs (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

MAP CobT binds to TLR4, but not TLR2. A and B, bone marrow-derived DCs from WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− mice were treated for 1 h with MAP CobT (10 μg/ml) and stained with an Alexa 488-conjugated anti-His monoclonal antibody. The percentage of positive cells is shown in each panel. Bar graphs show the mean ± S.E. of the percentages of MAP CobT-Alexa 488 in CD11c+ cells from three independent experiments. Statistical significance (***, p < 0.001) is indicated for MAP CobT-treated TLR2−/− compared with MAP CobT-treated WT DCs. C, immunoprecipitation (IP) with His, TLR2, or TLR4 antibodies and immunoblotting (IB) with His, TLR2, or TLR4 antibodies. DCs were treated for 6 h with MAP CobT (10 μg/ml). Cells were harvested and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-rat IgG, anti-mouse IgG, anti-His, anti-TLR2, or anti-TLR4. Proteins were visualized by immunoblotting with His, TLR2, or TLR4 antibodies. Total cell lysate was used as an input control. D, fluorescence intensities of anti-MAP CobT bound to MAP CobT-treated DCs. DCs derived from WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− mice were treated for 1 h with MAP CobT (10 μg/ml), fixed, and stained with DAPI and a Cy3-conjugated anti-MAP CobT antibody (scale bar, 10 μm).

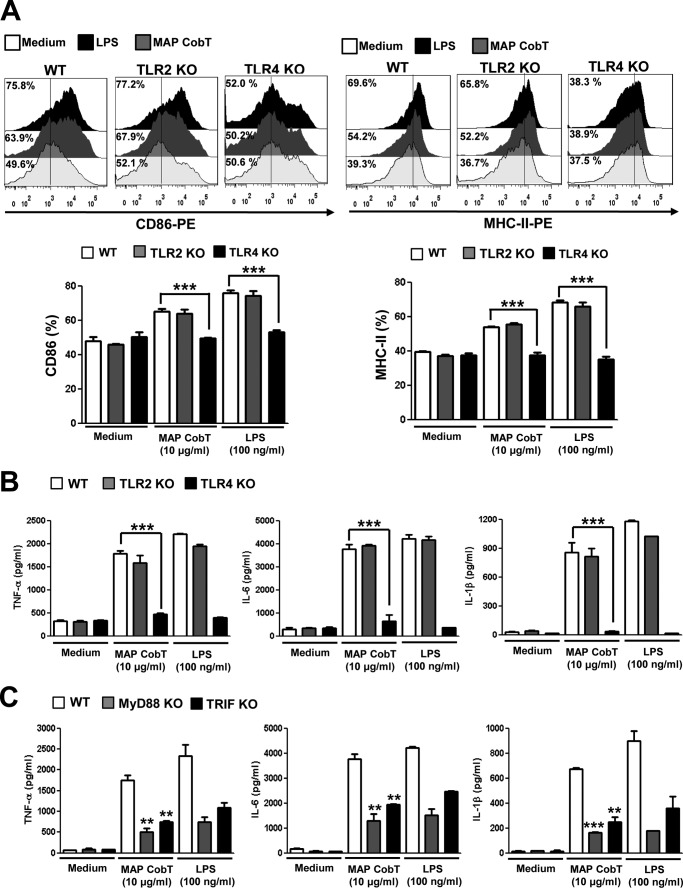

To test the ability of MAP CobT to activate DCs via TLR4, we measured surface molecule expression and proinflammatory cytokine production in MAP CobT-treated WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− DCs. MAP CobT enhanced surface molecule expression (Fig. 3A) and proinflammatory cytokine secretion (Fig. 3B) in WT or TLR2−/− DCs. In contrast, these effects were strongly diminished in TLR4−/− DC, indicating that MAP CobT is a TLR4 agonist in DCs.

FIGURE 3.

MAP CobT induces activation of DCs via interaction with TLR4. A, histograms showing CD86 or MHCII expression on MAP CobT-treated CD11c+-gated DCs derived from WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− mice. DCs derived from WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− mice were treated for 24 h with MAP CobT (10 μg/ml). The percentage of positive cells is shown for each panel. Bar graphs show the mean ± S.E. of the percentages for each surface molecule on CD11c+ cells in three independent experiments. Statistical significance (***, p < 0.001) is indicated for MAP CobT-treated TLR4−/− versus MAP CobT-treated WT DCs. B, DCs derived from WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− mice were treated for 24 h with MAP CobT or LPS. TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β production was measured by ELISA. C, DCs derived from WT, MyD88−/−, and TRIF−/− mice were treated for 24 h with MAP CobT (10 μg/ml) and LPS (100 ng/ml). TNF-α, IL-6, or IL-1β production was measured by ELISA. All data are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3) and statistical significance (***, p < 0.001) is indicated for treatments as compared with MAP CobT-treated WT DCs.

TLR4 is critical for the innate immune response via activation of signaling cascades with Toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptors, including MyD88 and TRIF (20). To investigate MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways in MAP CobT-induced cytokine production by DCs, we compared DC-based cytokine production in WT, MyD88−/−, and TRIF-deficient mice. MAP CobT-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β was significantly reduced in the absence of MyD88 and TRIF (Fig. 3C). Our results suggest that MyD88 and TRIF are crucial for an optimal MAP CobT-induced cytokine response. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MAP CobT induces DC maturation in a TLR4-dependent manner, increasing expression of cell-surface molecules and proinflammatory cytokines.

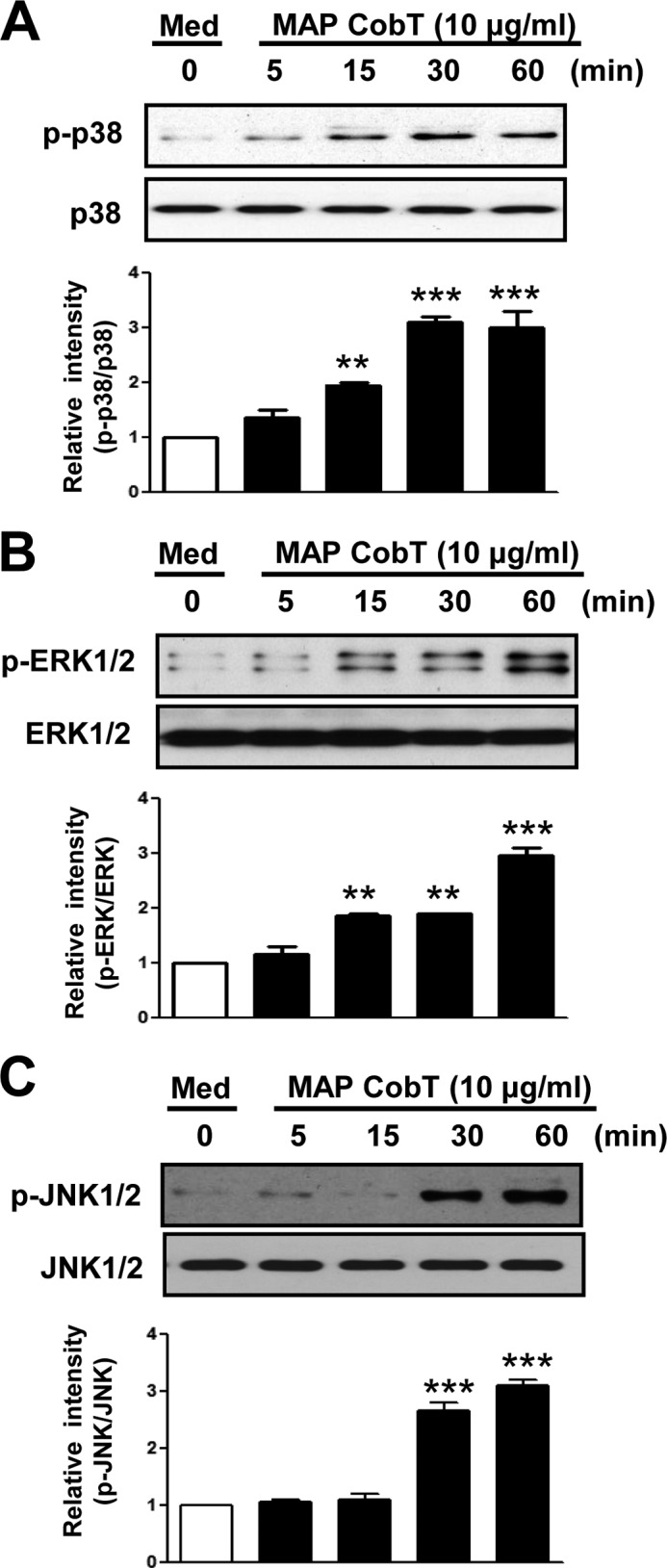

MAP CobT-induced Maturation of DCs Activates the MAPK and NF-κB Pathways

NF-κB and MAPKs are essential for DC maturation induced by mycobacterial antigens (17). Therefore, we examined whether MAP CobT activates NF-κB and MAPK in DCs. DCs were stimulated with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT, and MAPK phosphorylation (including ERK1/2, JNK1/2, and p38), IκBα phosphorylation/degradation, and p65 nuclear translocation were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 4, A-C, MAP CobT triggered p38, JNK1/2, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in DCs. In addition, we found that MAP CobT induced IκB-α phosphorylation and degradation as well as p65 nuclear translocation (Fig. 5, A-C). To confirm these observations, nuclear extracts were examined for NF-κB binding activity by EMSA using a palindromic NF-κB binding site. As expected, treatment of cells with MAP CobT generated prominent NF-κB complex binding (Fig. 5D). Then, we performed the supershift assay with specific antibodies against NF-κB subunits to characterize the nuclear κB-binding protein. The supershift assay analysis was performed with antibodies for NF-κB subunits NF-κB p65, p50, and p52. As shown in Fig. 5E, anti-p65 and p50 antibodies caused a supershift of nuclear κB proteins, whereas anti-p52 did not affect the nuclear κB-binding proteins. In addition, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays revealed that the DNA bindings of NF-κB (p65) to each Il-6 and Tnf-α promoter region were induced after treatment with MAP CobT (Fig. 5F).

FIGURE 4.

DC maturation triggered by MAP CobT involves activation of MAPKs. A–C, DCs were treated with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT and protein expression is shown over time. Cells lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses were performed using specific antibodies to phospho-p38 (p-p38), p38, phospho-ERK1/2 (p-ERK1/2), ERK1/2, phospho-JNK1/2 (p-JNK1/2), and JNK1/2. Relative band intensity of each protein is expressed as a percentage compared with the value of untreated controls. The results shown are typical of three experiments for each condition. The data are shown as mean ± S.E. (n = 3) and statistical significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001) is indicated for treatments versus untreated DCs.

FIGURE 5.

DC maturation triggered by MAP CobT involves activation of NF-κB signal pathway. A and B, DCs were treated with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT and protein expression is shown over time. Cells lysates or nuclear lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses were performed using specific antibodies to phospho-IκB-α (p-IκB-α), IκB-α (unphospho), and p65 NF-κB. β-Actin and lamin B were used as loading controls for cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively. Relative band intensity of each protein is expressed as a percentage compared with the value of untreated controls. The results shown are typical of three experiments for each condition. The data are shown as mean ± S.E. (n = 3) and statistical significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001) is indicated for treatments versus untreated DCs. C, effect of MAP CobT on the cellular localization of the p65 subunit of NF-κB in DCs. DCs were plated in covered glass chamber slides and treated for 1 h with MAP CobT. After stimulation, the p65 subunit in cells was evaluated by immunofluorescence as described under “Experimental Procedures” (scale bar, 10 μm). D, autoradiograph of EMSA performed with a 32P-labeled NF-κB nucleotide and nuclear extract from MAP CobT-treated DCs for the indicated time point. EMSA was performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” n.s. indicates nonspecific band. E, supershift assay was performed using specific antibodies against NF-κB subunits, p65, p50, and p52 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” F, ChIP assays were performed on treated with MAP CobT using anti-p65 antibody for the indicated time point as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

Next, to elucidate the functional roles of these kinases in MAP CobT-induced DC activation, we used specific pharmacological inhibitors or NF-κB super-repressor (IκBα dominant negative) and measured MAP CobT-induced proinflammatory cytokine production and co-stimulatory molecule expression. Cells were pre-treated for 1 h with a p38 inhibitor (SB203580), an ERK1/2 inhibitor (U0126), a JNK1/2 inhibitor (SP600125), NF-κB inhibitor (Bay 11-0782) or were transfected for 24 h with NF-κB super-repressor before exposure to MAP CobT. We found that these pharmacological inhibitors or NF-κB super-repressor significantly abrogated MAP CobT-induced surface expression of CD80 and CD86 (supplemental Figs. S2A and S3A) as well as decreased production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (supplemental Fig. S2B and S3B). The translocation of p65 from the cytosol to the nucleus was also decreased (supplemental Fig. S2C). Our results suggest that NF-κB and MAPK pathways are important signaling links in DC maturation and activation induced by MAP CobT.

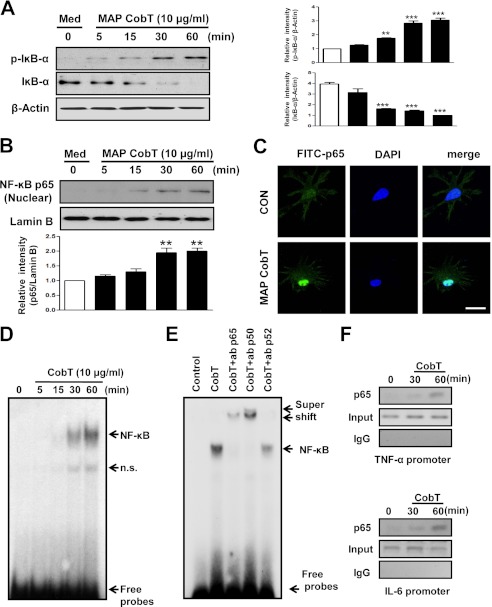

MAP CobT Induces CD8+ and CD4+ T Cell Proliferation via DC Activation

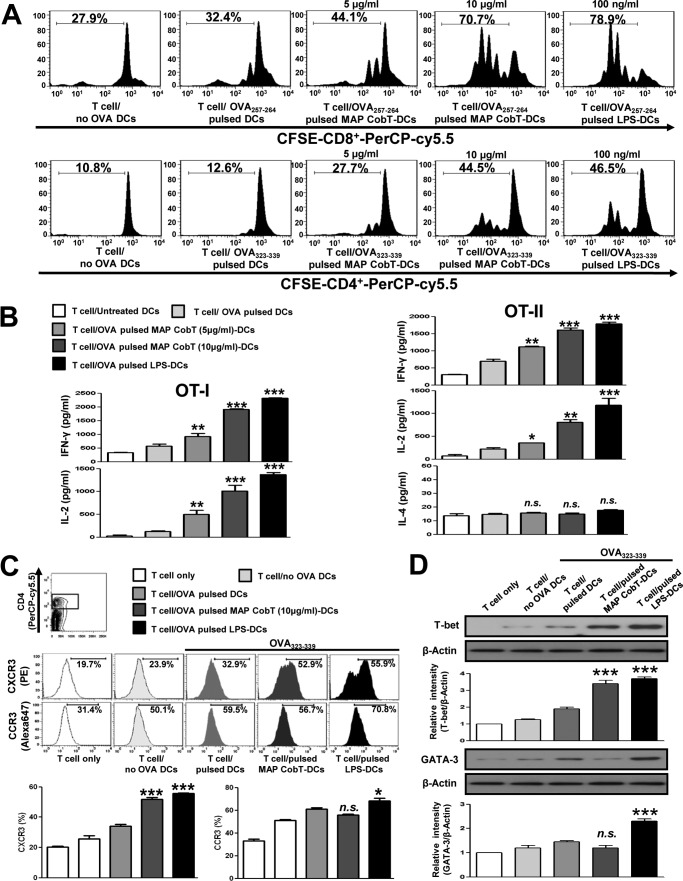

To ascertain whether DC maturation by MAP CobT stimulates T cells, we performed a syngeneic MLR assay using OT-I T cell receptor transgenic CD8+ T cells and OT-II T cell receptor transgenic CD4+ T cells. Transgenic CFSE-labeled OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with MAP CobT-treated DCs and pulsed with OVA(257–264) or OVA(323–339). These cells displayed an increase in proliferation compared with the same T cells co-cultured with DCs pulsed with OVA(257–264) or OVA(323–339) but without MAP CobT treatment (Fig. 6A). In addition, naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells primed with MAP CobT-treated DCs produced significantly higher IFN-γ and IL-2 levels (p < 0.05–0.01) than those primed with untreated DCs. Comparable IL-4 secretion was detected regardless of MAP CobT stimulation (Fig. 6B). We next investigated expression of CXCR3 and CCR3, which are associated with T cell polarization, in CD4+ T cells using flow cytometry. CXCR3 is preferentially expressed on Th1 cells, whereas Th2 cells express CCR3 (21). As shown in Fig. 6C, CD4+ T cells co-cultured with MAP CobT-treated DCs, and pulsed with OVA(323–339), showed a significant increase in CXCR3 expression compared with control cells. No changes in CCR3 expression were observed in the presence of MAP CobT. Furthermore, we also found that MAP CobT-treated DCs elevated T-box expressed in T cells (T-bet) expression in naive CD4+ cells, whereas the expression of GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA-3) was not observed (Fig. 6D). These results suggest that MAP CobT directs naive T cell populations toward the Th1 phenotype.

FIGURE 6.

MAP CobT-treated DCs stimulate T cells to produce Th1 cytokines. Transgenic OVA-specific CD8+ T cells and transgenic OVA-specific CD4+ T cells were isolated, stained with CFSE, and co-cultured for 96 h with DCs treated with MAP CobT (5 or 10 μg/ml) or LPS (100 ng/ml). Cells were pulsed with OVA(257–264) (1 μg/ml) for OVA-specific CD8+ T cells or OVA(323–339) (1 μg/ml) for OVA-specific CD4+ T cells, respectively. T cells co-cultured with untreated DCs served as controls. A, the proliferation of OT-1+ (Top) and OT-2+ (Bottom) T cells was assessed by flow cytometry. B, culture supernatants (obtained from the conditions described for A) were harvested after 24 h. IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 were measured by ELISA. C, splenocytes were stained with the CXCR3 monoclonal antibody or the CCR3 monoclonal antibody. The percentage of positive cells is shown for each panel. Histograms and bar graphs show CXCR3+CCR3+ T cells in OVA-specific CD4+ T cells. D, T-bet and GATA-3 expression in OVA-specific CD4+ T cells were assessed by immunoblotting using specific T-bet and GATA-3 monoclonal antibodies. The mean ± S.E. is shown for three independent experiments. Statistical significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001) is shown for treatments compared with the appropriate controls (T cell/OVA(257–264) pulsed DCs or T cell/OVA(323–339) pulsed DCs). n.s. indicates not significant.

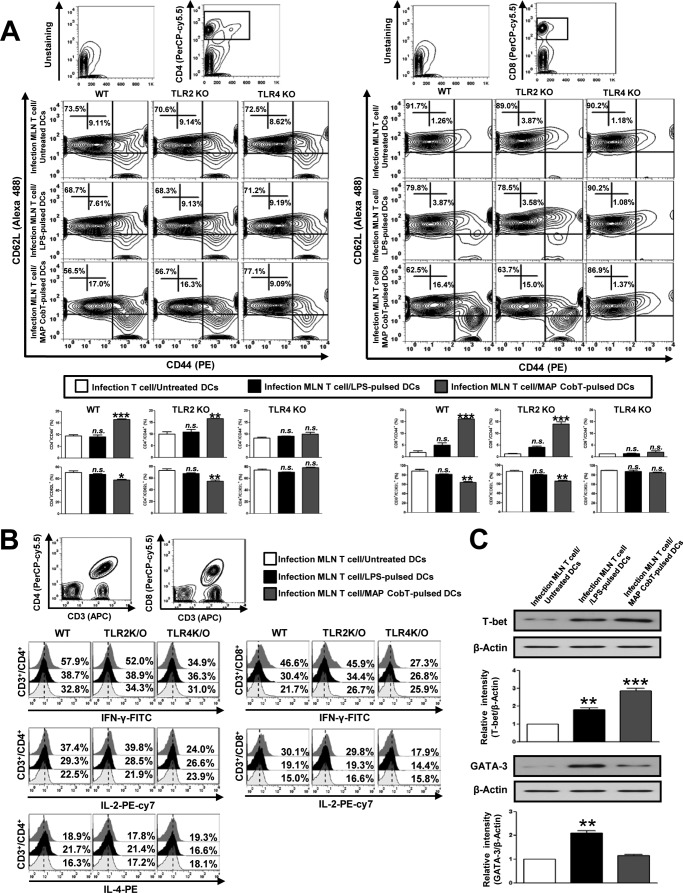

MAP CobT Induces Effector/Memory T Cell Development via TLR4-mediated DC Activation

To assess whether DC maturation mediated by MAP CobT enables the specific stimulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from MLN of MAP-infected mice, we used flow cytometry to analyze the surface expression of CD62L and CD44 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Naive T cells were previously reported to express a CD62LhighCD44low phenotype, whereas effector/memory T cells exhibit a CD44highCD62Llow phenotype (22). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from MLN of MAP-infected mice were co-cultured with MAP CobT-treated DCs derived from WT, TLR2−/−, or TLR4−/− mice. MAP CobT-treated WT and TLR2−/− DCs specifically induced the formation of effector/memory T cells as shown by down-regulated CD62L and up-regulated CD44 expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from MLN of MAP-infected mice compared with controls (Fig. 7A). This effect of MAP CobT was abrogated in TLR4−/− DCs. Interestingly, in the splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from MAP-infected mice, MAP CobT-treated DCs had less effect on down-regulated CD62L and up-regulated CD44 expression compared with the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from MLN (supplemental Fig. S4). In addition, the percentages of CD4-IFN-γ/CD4-IL-2 and CD8-IFN-γ/CD8-IL-2 double-positive cells were higher among T cells co-cultured with MAP CobT-pulsed WT or TLR2−/− DCs. The elevation of these cytokines was not observed in T cells co-cultured with MAP CobT-treated TLR4−/− DCs. Additionally, IL-4 expression in CD4+ cells from T cells treated with MAP CobT-pulsed DCs or LPS-pulsed DCs remained at baseline levels (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, we found that MAP CobT-treated DCs increased T-bet expression in effector/memory T cells but GATA-3 expression remained unchanged (Fig. 7C). These data suggest that MAP CobT-mediated DC activation activates effector/memory T cells in a TLR4-dependent manner and drives Th1 immune responses.

FIGURE 7.

MAP CobT-stimulated DCs induce the effector/memory T cell proliferation via TLR4 signaling. A, WT, TLR2−/−, and TLR4−/− DCs were cultured for 24 h with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT. The MAP CobT-matured DCs were washed and co-cultured for 3 days with allogeneic T cells at DC to a T cell ratio of 1:10. Mesenteric lymph nodes were stained with CD4, CD8, CD62L, and CD44 antibodies. Contour and bar graphs show CD62L+CD44+ T cells in the mesenteric lymph node. Bar graphs show the percentages (mean ± S.E.) for CD4+/CD44+CD62L+ and CD8+/CD44+CD62L+ T cells from three independent experiments. Statistical significance (**, p < 0.01 or ***, p < 0.001) is indicated for treatments compared with untreated DCs. n.s. indicates not significant. B, IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-4 expression in CD3+/CD4+ and CD3+/CD8+ cells was analyzed by intracellular IFN-γ, IL-2, or IL-4 staining in mesenteric lymph node T cells co-cultured with MAP CobT-pulsed DCs or LPS-pulsed DCs. The percentages of double-positive cells among the T cells are indicated in the top right corner. Results are representative of three independent experiments. C, WT DCs were cultured for 24 h with 10 μg/ml of MAP CobT. The MAP CobT-matured DCs were co-cultured for 3 days with mesenteric lymph node T cells from MAP-infected mice. T-bet and GATA-3 expression was assessed by immunoblotting using specific T-bet and GATA-3 monoclonal antibodies. The results shown are typical of three experiments for each condition. The data are shown as mean ± S.E. (n = 3). Statistical significance (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; or ***, p < 0.001) is indicated for treatments versus untreated DCs.

DISCUSSION

A variety of bacterial proteins are secreted or exported into the surrounding milieu during growth that play important roles in cell-cell communication, detoxification of harmful chemicals, eliciting host immune responses, and the killing of potential competitors (23, 24). In particular, many of the pathogenic mycobacteria cell wall-associated or secreted antigens are targets of host immune responses. Therefore, mycobacterial secretory proteins are considered candidate antigens for immune protection against mycobacterial diseases as well as reagents for immunological diagnoses (25, 26). Consequently, the precise characterization of mycobacterial secretory proteins is essential to understanding host-pathogen interactions and facilitating the development of prospective vaccine candidates.

As documented in previous studies, MAP culture filtrate contains more immunogenic antigens than cellular extracts (27, 28). Fourteen apparently specific proteins with potential diagnostic value for Johne disease in cattle were found in the culture filtrates of MAP JTC303 (ModD, PepA, ArgJ, CobT, Ag 85c, and nine as yet unnamed proteins) (16). Among these 14 proteins, MAP fibronectin attachment protein, also called ModD, was found to activate DCs and induce Th1 immune response polarization (7). Interestingly, ModD serologically reacts with sera from both MAP-infected cattle and patients with Crohn disease, indicting ModD acts as a T cell, as well as a B cell antigen (16, 29).

Like ModD, the CobT (35-kDa protein) was detected in culture filtrate of MAP (16). It is believed that the CobT enzyme is involved in the late steps of coenzyme B12 biosynthesis in bacteria such as Salmonella enterica and Lactobacillus reuteri (30, 31). However, the immunological function of CobT in interacting with DCs and its in vivo contribution to T cell immunity has not been studied. Thus, research regarding the role of CobT in inducing, maintaining, and regulating immune response could provide major insights into how CobT regulates innate and adaptive immunity in MAP infection.

Similar to the desire to develop an improved TB vaccine, it is important to characterize the vaccine potential of MAP because it is potentially associated with zoonotic disease (32, 33). Identification and characterization of novel MAP antigens that interact with host immune responses is an essential part in development of new drugs and effective vaccines against MAP infection. TLRs expressed on APC are key components of the innate immune system and stimulate the host immune responses to pathogens. Moreover, these receptors play a key role in promoting adaptive immune responses by initiating innate immunity against the infection (34). TLRs are also essential for T cell expansion, differentiation, and memory formation via activation of adaptive immune responses by APC maturation (35). Recent studies suggest that TLRs play a pivotal role in induction of Th1/Th2 immune responses through control of DCs (36, 37). Thus, TLRs represent potent targets for the development of various vaccines, including against mycobacterial diseases.

TLR2 and its related signaling pathways have been more emphasized in the mycobacteria fields than TLR4. Previously, we have reported that a M. tuberculosis antigen, Rv0577, regulates innate and adaptive immune responses against M. tuberculosis infection by interacting with TLR2 (38). However, studies have shown that C3H/HeJ mice harbor a mutation in the TLR4 signaling domain that renders them unresponsive to LPS, and have a reduced capacity to eliminate mycobacteria from the lungs, with the infection spreading to the spleen and liver (39). Thus, TLR4 signaling appears to be required to control the local growth and dissemination of mycobacterial infection from target organs. Recently, TLR4 agonists were described to have important immunoregulatory applications, such as adjuvants for vaccines in antitumor therapies (40). Moreover, an adjuvant study using M. tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin (HBHA), a TLR4 agonist, for cancer treatment has recently been reported (41). The signals through these receptors are mediated by either MyD88- and TRIF-dependent pathways and appear to be especially powerful immunopotentiators (41). In addition, many studies have highlighted the role of cell-based vaccines to evoke protective T cell responses against diseases, including cancer and infectious diseases (42, 43).

Although these studies have proposed various mechanisms for vaccine development or more effective therapies to defend against pathogenic infection, the immunological function and underlying mechanism of the MAP antigen is not understood. Here, we show that MAP CobT directly interacts with cell surface TLR4 and increases surface molecule expression and proinflammatory cytokine secretion by MAPK and the NF-κB pathway activation in DCs. Furthermore, MAP CobT was found to significantly induce IL-12p70 secretion, but not IL-10 secretion. IL-12p70 secreted by APCs induces the secretion of IFN-γ from T cells and plays a critical role in driving Thl immune responses (44). Thus, our findings indicate that MAP CobT is an agonist for TLR4 and contributes to Th1 polarization via DC maturation in a TLR4-dependent manner.

Detection of MAP-specific cell-mediated immune responses can serve as an alternative indicative method and be implemented as a diagnostic tool. In addition, cell-mediated immune responses can be measured at early stages of infection, prior to antibody development and shedding of detectable MAP amounts. Therefore, cell-mediated immune responses modulated by various T cell subsets are essential to provide protective immunity and prevent progression of MAP infectious disease. Previous studies have shown MAP antigens, such as 85A, 85B, 85C, and superoxide dismutase, induce a strong Th1 response and confer protection against MAP infection (45, 46). It has been reported that the fibronectin attachment protein of MAP induces CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation through TLR-mediated DC activation (7, 47). These activated T cells secrete IFN-γ and IL-2, which are known to mediate protective immune responses against MAP (7, 47). Furthermore, MAP0261c has been reported to stimulate a T cell response as well as induce a number of Th1 cytokines, including IFN-γ (48). Such findings provide strong evidence that MAP antigens may have a role in protective immune responses. Interestingly, our data show that MAP CobT enhances the immunostimulatory capacity of DCs to stimulate T cells, as well as IFN-γ and IL-2 secretion, in mixed-lymphocyte reactions stimulated by MAP CobT-matured DCs. In addition, we found that MAP CobT-treated DCs up-regulate CXCR3 expression in CD4+ T cells, whereas CCR3 expression remained at baseline levels. Moreover, we found that MAP CobT-treated DCs elevated T-bet expression in CD4+ cells but did not induce the expression of GATA-3, indicating that MAP CobT participates in adaptive immunity by directing T cell immune responses to a Thl polarization. Previously, it was reported that T-bet is expressed in developing CD4+ Th1 cells, driving IFN-γ production, Th1 differentiation, and repression of the alternate Th2 program (49). Taken together, our data indicate that direct binding of MAP CobT to TLR4 on DCs augments T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production, parameters that are crucial for protection against mycobacterial infection. Thus, MAP CobT can be employed in many biological fields.

Memory T cells are a cornerstone of protective immunity in immune responses against infection and are a key element in successful vaccination (50). Memory T cells are generally not able to fight infection directly, but they enable the body to react quickly and control a recognized pathogen if encountered again (50). Thus, understanding how memory T cells work will enable scientists to design more effective vaccines for human diseases. CD44 and CD62L are the most commonly used surface markers to define memory T cells because memory T cells express the CD44highCD62Llow surface phenotype. CD44 was previously identified as a surface marker of T cell activation and plays a role in Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation (51). CD62L is a lymph node homing receptor that is down-regulated upon activation of T cell populations (52). In our work, we demonstrated that a population of CD44highCD62Llow CD4+/CD8+ effectors was specifically generated from MLN of MAP-infected mice in response to DC-bearing MAP CobT, indicating that MAP CobT acts as a specific recall antigen. In addition, we showed that MAP CobT-treated DCs elevated the expression of T-bet in effector/memory T cells. In this regard, MAP CobT could be a potent adjuvant triggering Th1-mediated immune responses.

Conclusively, these findings demonstrate that MAP CobT plays a critical role in DC activation in a TLR4-dependent manner and the initiation of the adaptive immune response by polarizing the development of T cell immunity to a Th1 response. In view of these findings, MAP CobT should help in the design of new strategies to prevent of chronic diseases by MAP infection.

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by Korea government (MEST) Grant 2012-0004927.

This article contains supplemental Methods, Figs. S1–S4, and Table S1.

- DCs

- dendritic cells

- APCs

- antigen presenting cells

- MAP

- Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis

- MHC

- major histocompatibility complex

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- Th

- T helper

- IκB

- inhibitory κB

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor-κB

- T-bet

- T-box expressed in T cells

- GATA-3

- GATA-binding protein 3

- CCR3

- C-C chemokine receptor type 3

- MLN

- MLN, mesenteric lymph node

- CXCR3

- chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 3

- MyD88

- myeloid differentiation factor 88

- TRIF

- TIR domain containing adapter inducing interferon-β.

REFERENCES

- 1. Steinman R. M., Inaba K. (1999) Myeloid dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 66, 205–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reis e Sousa C. (2001) Dendritic cells as sensors of infection. Immunity 14, 495–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takeda K., Akira S. (2005) Toll-like receptors in innate immunity. Int. Immunol. 17, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lei L., Hostetter J. M. (2007) Limited phenotypic and functional maturation of bovine monocyte-derived dendritic cells following Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis infection in vitro. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 120, 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baksh F. K., Finkelstein S. D., Ariyanayagam-Baksh S. M., Swalsky P. A., Klein E. C., Dunn J. C. (2004) Absence of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in the microdissected granulomas of Crohn disease. Mod. Pathol. 17, 1289–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumgart D. C., Sandborn W. J. (2007) Inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet 369, 1641–1657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee J. S., Shin S. J., Collins M. T., Jung I. D., Jeong Y. I., Lee C. M., Shin Y. K., Kim D., Park Y. M. (2009) Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis fibronectin attachment protein activates dendritic cells and induces a Th1 polarization. Infect Immun. 77, 2979–2988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoek A., Rutten V. P., van der Zee R., Davies C. J., Koets A. P. (2010) Epitopes of Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis 70-kDa heat-shock protein activate bovine helper T cells in outbred cattle. Vaccine 28, 5910–5919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Santema W., van Kooten P., Hoek A., Leeflang M., Overdijk M., Rutten V., Koets A. (2011) Hsp70 vaccination-induced antibodies recognize B cell epitopes in the cell wall of Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis. Vaccine 29, 1364–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosseels V., Marché S., Roupie V., Govaerts M., Godfroid J., Walravens K., Huygen K. (2006) Members of the 30- to 32-kilodalton mycolyl transferase family (Ag85) from culture filtrate of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis are immunodominant Th1-type antigens recognized early upon infection in mice and cattle. Infect Immun. 74, 202–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Basagoudanavar S. H., Goswami P. P., Tiwari V. (2006) Cellular immune responses to 35-kDa recombinant antigen of Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis. Vet. Res. Commun. 30, 357–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McKenna K., Beignon A. S., Bhardwaj N. (2005) Plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Linking innate and adaptive immunity. J. Virol. 79, 17–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McShane H., Behboudi S., Goonetilleke N., Brookes R., Hill A. V. (2002) Protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis induced by dendritic cells pulsed with both CD8+- and CD4+-T-cell epitopes from antigen 85A. Infect. Immun. 70, 1623–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Diebold S. S. (2008) Determination of T-cell fate by dendritic cells. Immunol. Cell Biol. 86, 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rogers P. R., Dubey C., Swain S. L. (2000) Qualitative changes accompany memory T cell generation. Faster, more effective responses at lower doses of antigen. J. Immunol. 164, 2338–2346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cho D., Sung N., Collins M. T. (2006) Identification of proteins of potential diagnostic value for bovine paratuberculosis. Proteomics 6, 5785–5794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byun E. H., Kim W. S., Shin A. R., Kim J. S., Whang J., Won C. J., Choi Y., Kim S. Y., Koh W. J., Kim H. J., Shin S. J. (2012) Rv0315, a novel immunostimulatory antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, activates dendritic cells and drives Th1 immune responses. J. Mol. Med. 90, 285–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jeon J., Park K. A., Lee H., Shin S., Zhang T., Won M., Yoon H. K., Choi M. K., Kim H. G., Son C. G., Hong J. H., Hur G. M. (2011) Water extract of Cynanchi atrati Radix regulates inflammation and apoptotic cell death through suppression of IKK-mediated NF-κB signaling. J. Ethnopharmacol. 137, 626–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Druszczynska M., Wlodarczyk M., Fol M., Rudnicka W. (2011) Recognition of mycobacterial antigens by phagocytes. Postepy. Hig. Med. Dosw. 65, 28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takeda K., Kaisho T., Akira S. (2003) Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sallusto F., Mackay C. R., Lanzavecchia A. (2000) The role of chemokine receptors in primary, effector, and memory immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 593–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gerberick G. F., Cruse L. W., Miller C. M., Sikorski E. E., Ridder G. M. (1997) Selective modulation of T cell memory markers CD62L and CD44 on murine draining lymph node cells following allergen and irritant treatment. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 146, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wexler H. M. (2007) Bacteroides. The good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 20, 593–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tjalsma H., Bolhuis A., Jongbloed J. D., Bron S., van Dijl J. M. (2000) Signal peptide-dependent protein transport in Bacillus subtilis. A genome-based survey of the secretome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 64, 515–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Batoni G., Bottai D., Esin S., Florio W., Pardini M., Maisetta G., Freer G., Senesi S., Campa M. (2002) Purification, biochemical characterization and immunogenicity of SA5K, a secretion antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand. J. Immunol. 56, 43–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rosenkrands I., Weldingh K., Jacobsen S., Hansen C. V., Florio W., Gianetri I., Andersen P. (2000) Mapping and identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis proteins by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, microsequencing, and immunodetection. Electrophoresis 21, 935–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Roupie V., Viart S., Leroy B., Romano M., Trinchero N., Govaerts M., Letesson J. J., Wattiez R., Huygen K. (2012) Immunogenicity of eight Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis-specific antigens in DNA vaccinated and Map infected mice. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 145, 74–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roupie V., Leroy B., Rosseels V., Piersoel V., Noël-Georis I., Romano M., Govaerts M., Letesson J. J., Wattiez R., Huygen K. (2008) Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of DNA vaccines encoding MAP0586c and MAP4308c of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis secretome. Vaccine 26, 4783–4794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shin A. R., Kim H. J., Cho S. N., Collins M. T., Manning E. J., Naser S. A., Shin S. J. (2010) Identification of seroreactive proteins in the culture filtrate antigen of Mycobacterium avium ssp. paratuberculosis human isolates to sera from Crohn disease patients. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 58, 128–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Santos F., Vera J. L., van der Heijden R., Valdez G., de Vos W. M., Sesma F., Hugenholtz J. (2008) The complete coenzyme B12 biosynthesis gene cluster of Lactobacillus reuteri CRL1098. Microbiology 154, 81–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Claas K. R., Parrish J. R., Maggio-Hall L. A., Escalante-Semerena J. C. (2010) Functional analysis of the nicotinate mononucleotide:5,6-dimethylbenzimidazole phosphoribosyltransferase (CobT) enzyme, involved in the late steps of coenzyme B12 biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 192, 145–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hermon-Taylor J. (2000) Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis in the causation of Crohn disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 6, 630–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Greenstein R. J. (2003) Is Crohn disease caused by a mycobacterium? Comparisons with leprosy, tuberculosis, and Johne disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3, 507–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pasare C., Medzhitov R. (2005) Toll-like receptors. Linking innate and adaptive immunity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 560, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wille-Reece U., Flynn B. J., Loré K., Koup R. A., Miles A. P., Saul A., Kedl R. M., Mattapallil J. J., Weiss W. R., Roederer M., Seder R. A. (2006) Toll-like receptor agonists influence the magnitude and quality of memory T cell responses after prime-boost immunization in nonhuman primates. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1249–1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barton G. M., Medzhitov R. (2002) Control of adaptive immune responses by Toll-like receptors. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 380–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schnare M., Barton G. M., Holt A. C., Takeda K., Akira S., Medzhitov R. (2001) Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2, 947–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Byun E. H., Kim W. S., Kim J. S., Jung I. D., Park Y. M., Kim H. J., Cho S. N., Shin S. J. (2012) Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv0577, a novel TLR2 agonist, induces maturation of dendritic cells and drives Th1 immune response. FASEB J. 26, 2695–2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abel B., Thieblemont N., Quesniaux V. J., Brown N., Mpagi J., Miyake K., Bihl F., Ryffel B. (2002) Toll-like receptor 4 expression is required to control chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. J. Immunol. 169, 3155–3162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Apetoh L., Ghiringhelli F., Tesniere A., Obeid M., Ortiz C., Criollo A., Mignot G., Maiuri M. C., Ullrich E., Saulnier P., Yang H., Amigorena S., Ryffel B., Barrat F. J., Saftig P., Levi F., Lidereau R., Nogues C., Mira J. P., Chompret A., Joulin V., Clavel-Chapelon F., Bourhis J., André F., Delaloge S., Tursz T., Kroemer G., Zitvogel L. (2007) Toll-like receptor 4-dependent contribution of the immune system to anticancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Nat. Med. 13, 1050–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jung I. D., Jeong S. K., Lee C. M., Noh K. T., Heo D. R., Shin Y. K., Yun C. H., Koh W. J., Akira S., Whang J., Kim H. J., Park W. S., Shin S. J., Park Y. M. (2011) Enhanced efficacy of therapeutic cancer vaccines produced by co-treatment with Mycobacterium tuberculosis heparin-binding hemagglutinin, a novel TLR4 agonist. Cancer Res. 71, 2858–2870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Palucka A. K., Ueno H., Fay J. W., Banchereau J. (2007) Taming cancer by inducing immunity via dendritic cells. Immunol. Rev. 220, 129–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Moll H. (2003) Dendritic cells as a tool to combat infectious diseases. Immunol. Lett. 85, 153–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Trinchieri G., Pflanz S., Kastelein R. A. (2003) The IL-12 family of heterodimeric cytokines. New players in the regulation of T cell responses. Immunity 19, 641–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kathaperumal K., Park S. U., McDonough S., Stehman S., Akey B., Huntley J., Wong S., Chang C. F., Chang Y. F. (2008) Vaccination with recombinant Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis proteins induces differential immune responses and protects calves against infection by oral challenge. Vaccine 26, 1652–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shin S. J., Chang C. F., Chang C. D., McDonough S. P., Thompson B., Yoo H. S., Chang Y. F. (2005) In vitro cellular immune responses to recombinant antigens of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 73, 5074–5085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Noh K. T., Shin S. J., Son K. H., Jung I. D., Kang H. K., Lee S. J., Lee E. K., Shin Y. K., You J. C., Park Y. M. (2012) The Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis fibronectin attachment protein, a toll-like receptor 4 agonist, enhances dendritic cell-based cancer vaccine potency. Exp. Mol. Med. 44, 340–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huntley J. F., Stabel J. R., Bannantine J. P. (2005) Immunoreactivity of the Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis 19-kDa lipoprotein. BMC Microbiol. 5, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chakir H., Wang H., Lefebvre D. E., Webb J., Scott F. W. (2003) T-bet/GATA-3 ratio as a measure of the Th1/Th2 cytokine profile in mixed cell populations. Predominant role of GATA-3. J. Immunol. Methods 278, 157–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Esser M. T., Marchese R. D., Kierstead L. S., Tussey L. G., Wang F., Chirmule N., Washabaugh M. W. (2003) Memory T cells and vaccines. Vaccine 21, 419–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Guan H., Nagarkatti P. S., Nagarkatti M. (2009) Role of CD44 in the differentiation of Th1 and Th2 cells. CD44 deficiency enhances the development of Th2 effectors in response to sheep RBC and chicken ovalbumin. J. Immunol. 183, 172–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Høgevold H. E., Moen O., Fosse E., Venge P., Bråten J., Andersson C., Lyberg T. (1997) Effects of heparin coating on the expression of CD11b, CD11c, and CD62L by leucocytes in extracorporeal circulation in vitro. Perfusion 12, 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]