Background: Inhibitors of amyloid β (Aβ) peptide aggregation may lead to improved therapeutics for Alzheimer disease (AD).

Results: Compound D737, discovered in our high throughput screen (HTS), was effective in protecting against toxicity in vitro and in a Drosophila model of AD.

Conclusion: An inexpensive HTS was used to isolate novel inhibitors of Aβ aggregation.

Significance: This could lead to better molecular scaffolds for disease therapy.

Keywords: Aggregation, Alzheimer Disease, Amyloid, Drosophila, Drug Discovery

Abstract

Compelling evidence indicates that aggregation of the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide is a major underlying molecular culprit in Alzheimer disease. Specifically, soluble oligomers of the 42-residue peptide (Aβ42) lead to a series of events that cause cellular dysfunction and neuronal death. Therefore, inhibiting Aβ42 aggregation may be an effective strategy for the prevention and/or treatment of disease. We describe the implementation of a high throughput screen for inhibitors of Aβ42 aggregation on a collection of 65,000 small molecules. Among several novel inhibitors isolated by the screen, compound D737 was most effective in inhibiting Aβ42 aggregation and reducing Aβ42-induced toxicity in cell culture. The protective activity of D737 was most significant in reducing the toxicity of high molecular weight oligomers of Aβ42. The ability of D737 to prevent Aβ42 aggregation protects against cellular dysfunction and reduces the production/accumulation of reactive oxygen species. Most importantly, treatment with D737 increases the life span and locomotive ability of flies in a Drosophila melanogaster model of Alzheimer disease.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)2 is a progressive and fatal brain disorder affecting as many as 6 million Americans, yet there are currently no effective treatments targeting the underlying molecular cause of this debilitating neurodegenerative disease (1–5). Pathologically, the AD brain at its end stage is characterized by atrophy of the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, as well as accumulation of extracellular proteinaceous insoluble plaques composed of amyloid, a fibrillar form of protein. These amyloid plaques contain ordered assemblies of the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide (specifically the 42-residue alloform, Aβ42) (6–12).

Several pathogenic species that precede plaque formation have been isolated from AD brains. These include soluble low molecular weight (LMW) oligomers (dimers to dodecamers), Aβ-derived diffusible ligands or high molecular weight (HMW) oligomers (globular structures <5 nm in diameter), protofibrils (circular prefibrils 5–100 nm in diameter), and fibrils. The exact pathway of Aβ42 aggregation is not fully understood, and several competing pathways may occur simultaneously. A general view of the aggregation of soluble monomers into insoluble fibrils involves the following features: (i) nucleation dominated by a short lag phase, (ii) formation of LMW oligomers (dimers to dodecamers), (iii) assembly of LMW oligomers into larger β-sheet-rich oligomeric states, and (iv) growth of the β-sheet-rich oligomers into higher order aggregates of heterogeneous size and morphology. (v) Ultimately, the higher order oligomeric intermediates disappear with the formation of fibrils (11–14).

Although fibrils were once thought to be the molecular culprit in AD, recent studies show a more decisive correlation between the levels of soluble Aβ oligomers and the extent of synaptic loss and cognitive impairment (14). The link between Aβ aggregation, cellular dysfunction, and AD suggests that inhibition of Aβ oligomerization may ultimately lead to therapeutics that prevent and/or treat AD (8, 15–17).

Here, we describe the isolation and characterization of aggregation inhibitors discovered by implementing a high throughput screen (HTS) based on the fluorescence of Aβ42-GFP fusions (18, 19). A compound, hereafter called D737, was the most potent aggregation inhibitor identified by the screen. We show that D737 inhibited formation of specific aggregates of Aβ42 and protected against Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity. Specifically, D737 was most effective in reducing the toxicity of the HMW oligomers. Most importantly, D737 increased the life span and locomotive ability of flies in a Drosophila model of AD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

High Throughput Screening

For small molecule prescreening, isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (1 mm final concentration) was added to LB medium, and 20 μl of medium was dispensed into each well of 384-well plates (black with clear flat bottoms; Corning). Compounds were prescreened for inherent fluorescence by adding 300 nl of compound to the medium. Stock compound libraries were dispensed by the CyBi-Well 96- and 384-channel simultaneous pipettor (CyBio) with a 384-channel/300-nl dispensing pin. All compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and pure DMSO was used as the negative control. After compound addition, plates were read at the GFP wavelength (485 nm excitation and 510 nm emission) on an EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Each plate was screened in duplicate. Following this prescreen, we screened for aggregation inhibitors as follows. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells containing the Aβ42-GFP fusion plasmid were grown at 37 °C to A600 = 0.5. Then, 20 μl of this culture was added to each well already containing each compound (in duplicate) and isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (to induce protein expression). The final compound concentration was ∼75 μm. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 5 h without shaking or plate covers. After incubation, plates were read as described above.

Compounds

The eight compounds shown in Fig. 2 were purchased from ChemDiv (San Diego, CA).

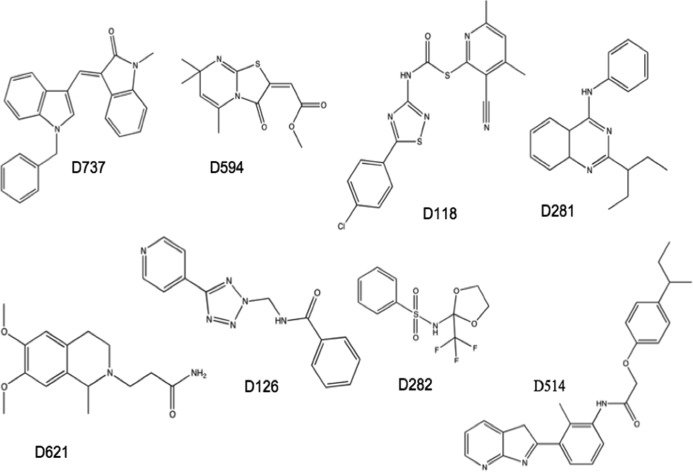

FIGURE 2.

Structures of eight compounds selected from the Aβ42-GFP screen.

Synthetic Peptide

Aβ42 peptide (unpurified) was purchased from the W. M. Keck Facility at Yale University and purified on a Vydac C4 reverse phase column. After purification, the peptide was snap-frozen and lyophilized. Monomeric samples were prepared by adding TFA and sonicating for 15 min. Residual TFA was removed by hexafluoroisopropanol and argon blow. For all cell culture experiments, lyophilized synthetic Aβ42 peptide was incubated for 24 h at 200 μm in a small amount of DMSO and 1× Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline enhanced with CaCl2 and MgCl2 (Invitrogen). 10 μl of Aβ42 with or without test compounds was added to cells to a final concentration of 20 μm peptide.

Thioflavin T Assays

Synthetic Aβ42 peptide was dissolved in DMSO and then diluted in PBS buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4 and 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.20–7.40) to a final concentration of 20 μm. Samples were incubated with and without test compound at 37 °C under quiescent conditions (no agitation) or shaking conditions (250 rpm) for the indicated periods. At various time points, 100 μl of peptide was placed in each well of 96-well plates (black with clear flat bottoms; Corning) with 200 μl of thioflavin T (ThT) stock solution (7 μm ThT and 50 μm glycine, pH 7.10). Fluorescence was measured at 483 nm (excitation at 450 nm) on a Varioskan plate reader.

Cell Toxicity

PC12 cells (American Type Culture Collection), derived from rat adrenal medulla pheochromocytoma, were cultured in 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 complete growth medium and grown to confluency. Cells were plated in tissue culture-treated flat bottom 96-well plates (clear; Corning) at 10,000 cells/well and allowed to attach overnight before adding peptide. Aβ42 peptide was incubated at 200 μm in buffer in the presence or absence of inhibitors for the indicated time periods. 10 μl of Aβ42 peptide incubated with or without test compounds was added to the cells to a final concentration of 20 μm peptide and compound. Following incubation with cells for 24 h at 37 °C, cell viability was evaluated using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (Roche Applied Science). Briefly, 10 μl of MTT was added to each well. After incubation for 4 h at 37 °C, 100 μl of solubilization solution was added and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Absorbance was recorded at 570 nm.

Determination of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species

Accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was monitored using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (Sigma). 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate is non-fluorescent but becomes fluorescent upon reaction with free radicals to form dichlorofluorescein (DCF). PC12 cells were grown under the same conditions as described for the cell toxicity assay. Cells were incubated for 24 h with synthetic Aβ42 peptide (final concentration of 20 μm) with or without various concentrations of D737. 10 μm 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate dissolved in water was added to the treated cells, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Cells were then washed twice with buffer. Care was taken during washing to ensure that the concentration of cells and substrates remained consistent. The fluorescence intensity of DCF was monitored on a Varioskan plate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 530 nm, respectively.

Fly Crosses

Transgenic Drosophila melanogaster flies expressing Aβ42 were generated by crosses as described by Crowther et al. (36). Before crossing, flies were reared on standard cornmeal-agar medium and kept at room temperature. Virgin female flies carrying the Aβ42 or Aβ42(E22G) transgene under the control of the upstream activation sequence promoter in a homozygous condition were collected no longer than 10 h post-eclosion. Female virgins were crossed with male flies carrying the driver elavC155-Gal4 on their X chromosome. This results in first generation female offspring expressing Aβ42 or Aβ42(E22G) in their central nervous system. Wild-type Oregon-R flies reared in the same medium served as controls. Flies were crossed on medium containing the indicated concentration of inhibitor. Medium was made by dissolving the compounds (from DMSO stocks) or a similar volume of DMSO in cornmeal-agar medium liquefied in a water bath. Medium containing a compound or DMSO was prepared weekly, aliquoted into vials, and stored at 18 °C until used. Flies were kept at 29 °C to promote transgene expression.

Fly Longevity

Assays were performed as described by Crowther et al. (36). Post-eclosion, 100 female wild-type flies or flies expressing transgenes were collected in groups of 20 in 10-cm glass vials containing inhibitor or DMSO. Flies were kept at 29 °C in vials containing cornmeal-agar medium with the test compound throughout life, and food was changed two to three times per week. Viable flies were counted daily. Median survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier statistics, and significance was calculated with the two-tailed TTEST function in Microsoft Excel.

Fly Climbing

Locomotive ability was assessed as described by Crowther et al. (36). 10-cm vials containing 20 flies each were tapped gently on the table. The number of flies that climbed to the top of the vial was recorded after 18 s. Results represent the fraction of flies climbing to the top compared with age-matched control flies.

RESULTS

High Throughput Screening Enables the Discovery of Novel Aβ Aggregation Inhibitors

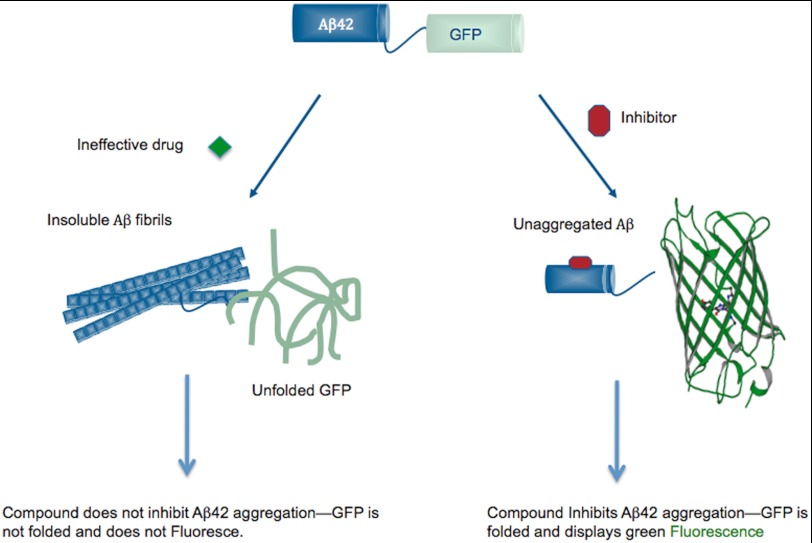

To search for small molecules that inhibit the aggregation of Aβ42, we utilized a HTS developed previously in our laboratory (18). This screen uses fluorescence from the proper folding of GFP as a reporter for Aβ42 aggregation. The screen is based on the finding that the Aβ42-GFP fusion protein expressed in E. coli does not fluoresce because the aggregation and/or insolubility of the upstream Aβ42 sequence prevents the correct folding and subsequent fluorescence of the downstream GFP. Compounds that inhibit Aβ42 aggregation and allow GFP to fold can be found by screening for fluorescence (Fig. 1) (18, 19). This screen is nonspecific and, in principle, should enable isolation of compounds that inhibit the formation of LMW oligomers, HMW oligomers, and/or fibrils.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the fluorescence-based screen using the Aβ42-GFP fusion. In the absence of inhibition, the Aβ42 portion of the fusion aggregates rapidly and causes the entire Aβ42-GFP fusion to misfold and aggregate. Therefore, no fluorescence is observed. However, inhibition of Aβ42 aggregation by a small molecule enables GFP to form its native green color.

E. coli is an artificial system for AD, and screening in E. coli has advantages and disadvantages. The advantages include that the screen is high throughput, low cost, and reproducible. An additional advantage is that screening in E. coli favors drug-like compounds that are nontoxic and readily penetrate biological barriers. Nonetheless, some potentially useful compounds may not enter bacterial cells and may produce false negatives.

We implemented the Aβ42-GFP screen on a library of 65,000 organic compounds in the collection at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. Compounds (or DMSO controls) were dispensed into 384-well plates for prescreening at the GFP fluorescence wavelength. Those compounds that fluoresced at this wavelength were discarded. (655 of 65,000 compounds were eliminated due to compound fluorescence. The cutoff was a composite Z of >3.) After this prescreen, E. coli cells harboring a plasmid expressing the Aβ42-GFP fusion were added to each well. Isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to induce protein expression, and samples were incubated for 5 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, GFP fluorescence was measured for each well. Compounds that enabled fluorescence of the Aβ42-GFP reporter at a level >3 S.D. above the DMSO control were identified as putative inhibitors of aggregation (20). Of the 65,000 compounds screened, the assay identified 269 hits. From these, eight readily available compounds were chosen for further testing (Fig. 2).

Selected Compounds Inhibit the Formation of Fibrils

Previous research suggests that aggregation inhibitors fall into three classes: those that inhibit fibrillization but not oligomerization, those that inhibit oligomerization but not fibrillization, and those that inhibit both (16). Therefore, we first determined whether the eight compounds (Fig. 2) inhibit fibril formation. Assays to identify fibril inhibitors were performed using ThT, a dye that is negligibly fluorescent in solution but displays significant fluorescence upon binding to amyloid fibrils. ThT fluorescence is proportional to the weight concentration of fibrils; therefore, ThT can be used to estimate the quantity of fibrils irrespective of their number or length distribution (21).

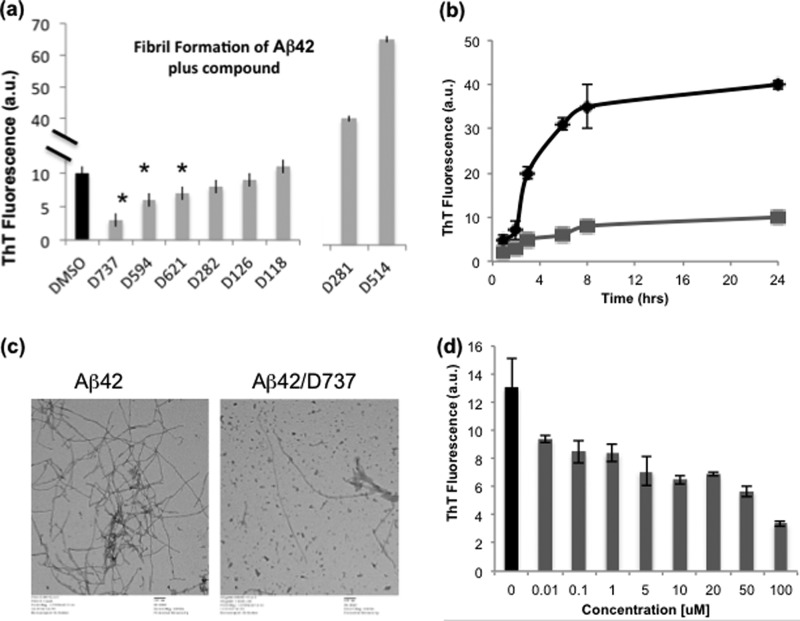

To assess the effects of the small molecule inhibitors on fibril formation, each compound (or DMSO control) was added at 100 μm to a 20 μm sample of synthetic Aβ42 peptide. Samples were incubated with shaking at 250 rpm and 37 °C, conditions shown previously to enhance fibrillization (22, 23). Following 5 h of incubation, aliquots were removed and added to ThT. Fluorescence measurements showed that compound D737 significantly inhibited fibril formation, whereas compounds D594, D621, D282, D126, and D118 were somewhat less effective. Compounds D281 and D514 produced large increases in ThT fluorescence, suggesting that these compounds either stimulate fibrillogenesis or cause fibrils to assume altered conformations with enhanced ThT binding and/or fluorescence (Fig. 3a).

FIGURE 3.

Small molecules inhibit fibril formation. a, ThT assays showed that several compounds isolated in the HTS inhibited the fibrillization of Aβ42. *, p < 0.05 relative to the control: D737, p = 0.001; D594, p = 0.008; and D621, p = 0.021. (Two compounds, D281 and D514, produced large increases in ThT fluorescence, suggesting that these compounds either stimulate fibrillogenesis or cause fibrils to assume altered conformations with enhanced ThT binding and/or fluorescence.) b, time course of inhibition of Aβ42 fibrillization by D737. Black line, 20 μm Aβ42 without D737; gray line, 20 μm Aβ42 with 50 μm D737. c, transmission EM of Aβ42 fibril formation in the absence or presence of 50 μm D737. d, dose-dependent inhibition of Aβ42 fibrillization by compound D737. a.u., absorbance units.

The results presented in Fig. 3a show a single concentration monitored at a single time point. These data were used as a rapid screen to choose one compound for more detailed studies at various different concentrations and time points. Because D737 was the most promising inhibitor, we chose this compound for further studies. Fig. 3b shows a time course for D737 and reveals that 50 μm D737 continued to inhibit the formation of ThT-responsive fibrils even after 24 h of incubation, conditions that caused extensive fibrillization of the DMSO control. EM confirmed this finding by showing that control samples formed extensive fibrils after 24 h, whereas samples treated with 50 μm D737 produced substantially fewer fibrils (Fig. 3c). For compound D737, we also measured the concentration dependence of inhibition. Aβ42 (20 μm) was incubated under fibrillization conditions for 6 h in the presence of various concentrations of D737. These studies showed that D737 inhibited fibrillization with an IC50 of ∼10 μm (Fig. 3d).

Compound D737 Inhibits the Formation of Aβ42 Oligomers

It is not clear which of the many oligomeric species in the Aβ42 aggregation pathway is most toxic. Some studies implicate LMW oligomers, whereas others implicate HMW oligomers or even fibrils (24–26). Therefore, we probed the ability of D737 to inhibit the formation of each of these species. The ability of compounds to inhibit fibril formation was monitored by ThT and EM as described above. Characterization of oligomers is more challenging because of inherent difficulties in trapping and quantifying various oligomeric forms. Furthermore, preparations of oligomers tend to contain heterogeneous mixtures of LMW and HMW aggregates, which are difficult to separate (25, 26). Nonetheless, it was possible to analyze mixtures of LMW and HMW oligomers by following the kinetics of aggregation.

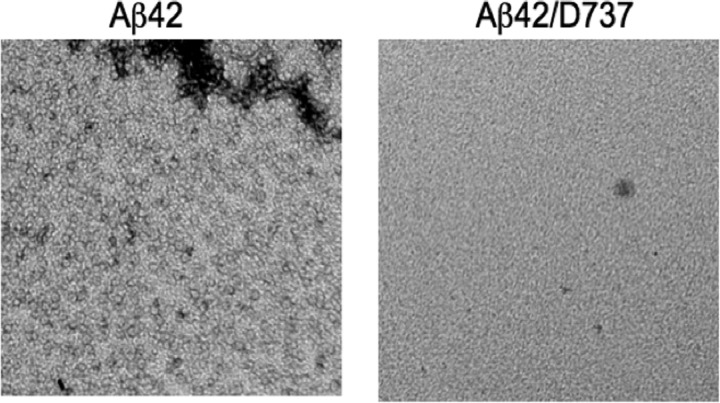

To produce soluble oligomers, 20 μm Aβ42 peptide was incubated for 0, 8, and 24 h under oligomerization conditions: high salt at 37 °C without agitation. These conditions have been shown to produce Aβ42 oligomers that are free of fibrils at early time points (26). To determine the ability of D737 to inhibit oligomerization, Aβ42 peptide was incubated with or without 50 μm D737. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was assayed for oligomers.

Prior to incubation, 20 μm Aβ42 showed very little aggregation by EM (data not shown). However, SDS gel electrophoresis studies showed that LMW Aβ42 oligomers, such as tetramers, hexamers, and larger oligomers of various sizes, formed during the first 8 h of incubation. Compound D737 did not inhibit the formation of these LMW oligomers (supplemental Fig. 1).

HMW oligomers could be observed by EM, and as shown in Fig. 4, Aβ42 formed small circular oligomers after 24 h of incubation. These circular structures, which have been implicated as a major neurotoxic species in AD pathogenesis (25), were not present when Aβ42 was incubated with 50 μm D737 (Fig. 4). In summary, these aggregation assays suggest that compound D737 does not prevent the formation of LMW oligomers (supplemental Fig. 1) but has a significant inhibitory effect on the formation of both fibrils (Fig. 3) and HMW oligomers (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

Transmission EM images of Aβ42 oligomers formed after 24 h of incubation in the absence or presence of 50 μm compound D737.

Compound D737 Reduces Aβ-induced Cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity studies were performed using both LMW and HMW oligomers, and fibrils produced by the protocols described above. To test whether D737 can inhibit the formation of cytotoxic oligomers, we dissolved Aβ42 in pure DMSO or in DMSO containing compound D737. Oligomerization was initiated by adding phosphate buffer to produce a final concentration of 20 μm peptide and 40 μm D737. Samples were incubated under oligomerization conditions for various amounts of time. Following incubation, samples were centrifuged to remove insoluble material, and the oligomer-rich supernatant was added to rat PC12 neuronal cells. Cell viability was analyzed using the MTT assay (27).

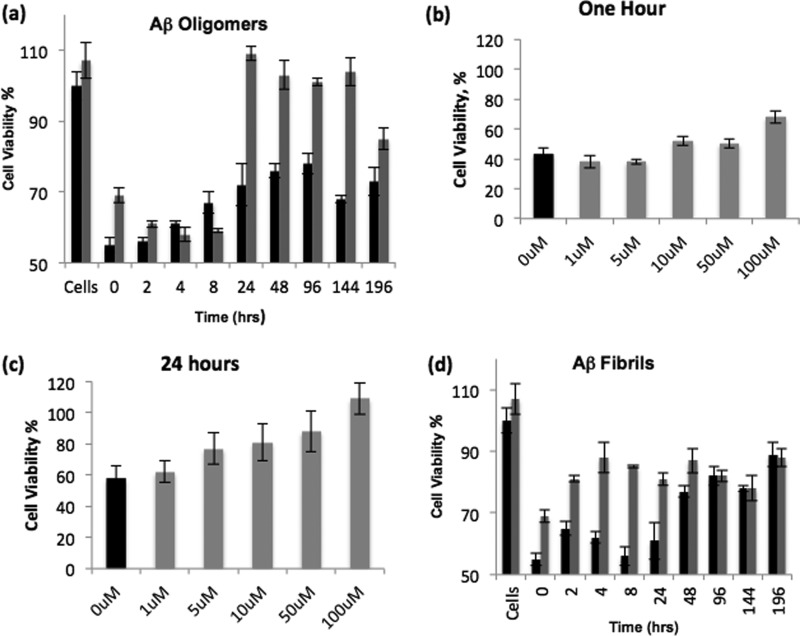

The results show an excellent correlation between the ability of D737 to inhibit the formation of various oligomers and its ability to reduce Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity. For example, during the first 8 h of quiescent incubation, Aβ42 formed LMW oligomers, such as tetramers, hexamers, and dodecamers. These oligomers reduced cell viability by ∼50% in the PC12 cell viability assay (Fig. 5a). Formation of these LMW oligomers was not inhibited by D737 (see above and supplemental Fig. 1); therefore, at early time points, D737 does not significantly reduce Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 5a). In contrast, HMW oligomers were present after 24 h of incubation and reduced cell viability by 30% (Fig. 5a). D737 inhibited the formation of these HMW oligomers (Fig. 4) and reduced their cytotoxicity (Fig. 5a). After 168 h, the predominant species was fibrils. As shown in Fig. 3, D737 reduced fibril formation, and as shown in the later time points in Fig. 5a, D737 reduced the cytotoxicity of these samples.

FIGURE 5.

Compound D737 rescues cells from the cytotoxic effect of Aβ42. The results represent percentage of viable cells compared with untreated cells. a, effect of D737 on the cytotoxicity of Aβ42 oligomers. 20 μm Aβ42 was incubated in the absence (black bars) or presence (gray bars) of 40 μm D737 for the indicated times under oligomerization conditions before being added to PC12 cells. b, D737 showed slight dose-dependent rescue from toxicity caused by Aβ42 oligomers formed during 1 h of incubation. c, D737 showed significant dose-dependent rescue from cytotoxicity caused by Aβ42 oligomers formed after 24 h of incubation. d, effect of D737 on the cytotoxicity of Aβ42 fibrils. 20 μm Aβ42 was incubated under fibrillization conditions in the absence (black bars) or presence (gray bars) of 40 μm D737 for the indicated times before being added to PC12 cells.

Additional analysis showed that the inhibition of Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity by D737 was dose-dependent. The toxicity of LMW oligomers formed after 1 h was not affected by concentrations <10 μm and was only slightly reduced by higher concentrations of D737 (Fig. 5b). On the other hand, the cytotoxicity of HMW oligomers formed after 24 h was reduced by ∼20% by 5 μm D737 and showed a dose-dependent reduction in toxicity from 4% at 1 μm to 50% at 100 μm D737 (Fig. 5c). This result further validates the finding that D737 is more effective in preventing the formation of HMW oligomers.

To test whether D737 can protect against the toxicity of insoluble HMW oligomers and fibrils, we incubated 20 μm peptide and 40 μm D737 (or DMSO control) at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm. As noted above, these conditions produced a mixture of HMW oligomers and fibrils for the first for 8 h and a higher concentration of fibrils after 8 h of incubation. We separated soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation and tested the cytotoxicity of the insoluble material by removing soluble oligomers in the supernatant and reconstituting the insoluble fraction in the original volume with water. The material present after 2–8 h of incubation (insoluble HMW oligomers and fibrils) reduced cell viability substantially (Fig. 5d). However, the addition of D737 reduced the cytotoxicity of Aβ42 incubated for these time periods (Fig. 5d). This result is consistent with the observations described above that D737 inhibited the formation of insoluble HMW oligomers and fibrils (Figs. 3 and 4). The time point at 24 h in Fig. 5d shows that D737 had a dramatic effect in restoring cell viability. This is consistent with its ability to prevent the formation of large insoluble oligomers, as shown in Fig. 4. Samples at time points from 48 to 196 h contained mostly late stage fibrils, which are less toxic than HMW oligomers or early stage fibrils. Not surprisingly, at these later time points, D737 had less of an effect on cytotoxicity (Fig. 5d).

Overall, there is excellent correlation between the ability of D737 to inhibit aggregation and its efficacy in reducing Aβ42-induced toxicity: D737 reduced the toxicity of both soluble HMW oligomers produced by 24 h of incubation under oligomerization conditions (Fig. 5a) and insoluble HMW oligomers produced by 2–24 h of incubation under fibrillization conditions (Fig. 5d). D737 also inhibited fibril formation and therefore reduced the toxicity of fibrils present after either 196 h of incubation under oligomerization conditions or 8 h of incubation under fibrillization conditions (Fig. 5, a and d).

Compound D737 Protects against Aβ42 Induction of ROS

The cytotoxic effects of Aβ42 aggregation have been linked to increased production and/or accumulation of ROS. Therefore, we were eager to test whether inhibition of Aβ42 aggregation by D737 can reduce the accumulation of ROS.

In principle, a compound could protect against the toxic effects of ROS either by preventing Aβ from forming toxic oligomers or by having an inherent antioxidant activity (28–30). To test whether D737 is a general antioxidant, we used hydrogen peroxide, a precursor of hydroxyl radicals, to induce oxidative stress in PC12 cells (28–31). Cells were incubated with several concentrations of H2O2, and viability was determined using the MTT assay. We estimated that 200 μm H2O2 reduced cell viability by ∼50% (supplemental Fig. 2). Therefore, this concentration was used for subsequent experiments.

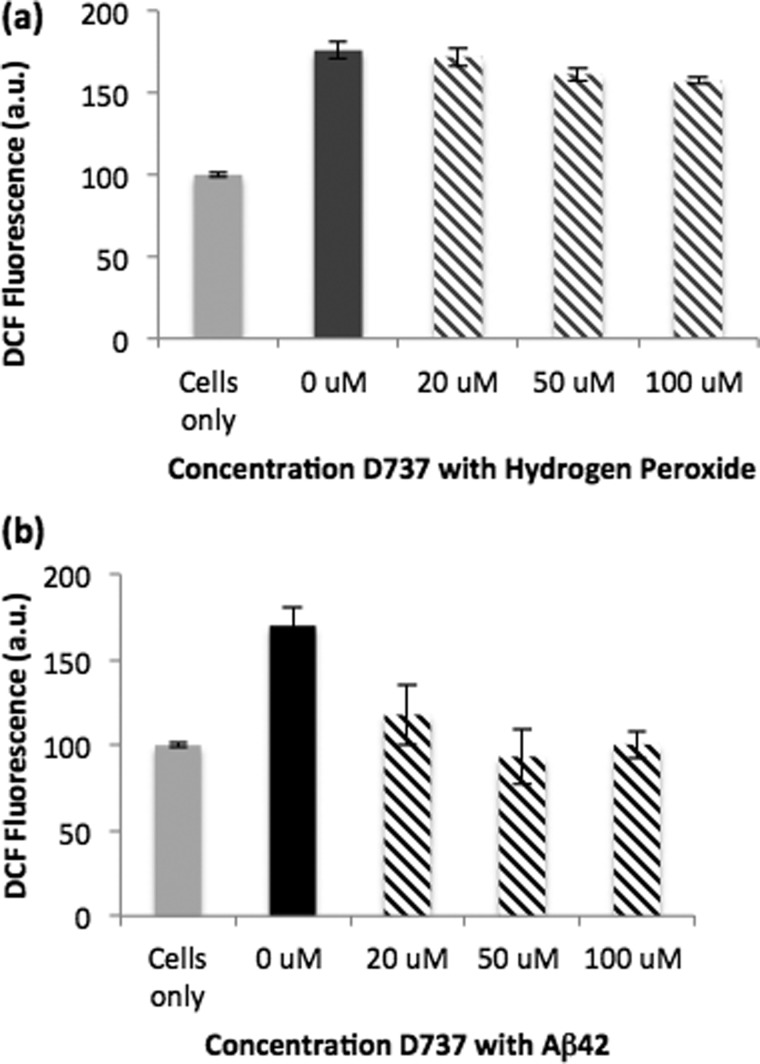

Accumulation of ROS was monitored using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate, a non-fluorescent compound that diffuses into cells and reacts with intracellular free radicals to produce the fluorescent product DCF. Thus, fluorescence of the DCF product can be used to monitor the amount of intracellular oxygen radicals (31). For a control, we showed that D737 on its own (in the absence of H2O2) did not cause an increase in DCF fluorescence (supplemental Fig. 3). PC12 cells incubated with 200 μm H2O2 for 24 h showed an 80% increase in DCF fluorescence. When the same incubations were performed in the presence of D737 at concentrations of 20, 50, or 100 μm, only a weak nonspecific reduction in DCF fluorescence was observed at higher concentrations (Fig. 6a). Overall, this indicates that D737 does not act as an antioxidant to reduce the accumulation of ROS.

FIGURE 6.

Change in ROS accumulation in the presence of various concentrations of D737. DCF fluorescence of cells incubated with water as a positive control was normalized to 100% (light gray bars). DCF fluorescence above 100% indicates increased accumulation of ROS. a, D737 did not significantly affect ROS accumulation induced by hydrogen peroxide. PC12 cells were incubated for 24 h with 200 μm H2O2 (dark gray bar) or D737 and 200 μm H2O2 (hatched gray bar). b, D737 reduced the ROS accumulation induced by Aβ42. PC12 cells were incubated for 24 h with 20 μm Aβ42 (black bar) or Aβ42 and various concentrations of D737 (hatched black bars). a.u., absorbance units.

Next, we tested the ability of D737 to reduce the ROS accumulation induced by Aβ42. 20 μm Aβ42 was incubated with PC12 cells for 24 h alone or in the presence of 20, 50, or 100 μm D737. In the absence of D737, Aβ42 increased ROS accumulation by 70% (Fig. 6b). However, in the presence of 20 μm D737, ROS increased by only 17%, and at concentrations of 50 or 100 μm, D737 completely inhibited the production of Aβ42-induced ROS (Fig. 6b). Presumably, this reduction in ROS accumulation results from the ability of D737 to inhibit the formation of Aβ42 oligomers.

Effects of D737 on Transgenic D. melanogaster

To test whether compound D737 is active in vivo, we used a transgenic fly model created by Crowther et al. (32). These flies express the human Aβ42 peptide in their CNS. Compared with wild-type Drosophila, they show reduced longevity and exhibit a gradual decline in locomotive ability (32–38). We tested the effects of D737 in transgenic flies expressing either wild-type Aβ42 or the Aβ42(E22G) (Arctic) mutation. This mutation causes Aβ42 to form more abundant protofibrils (HMW oligomers), which have been shown to be more toxic than fibrils (Fig. 5d) (34).

In the transgenic flies, Aβ42 is expressed under the control of a Gal4-upstream activation sequence system. Male stocks carry the pan-neuronal elav-Gal4 on their X chromosome, whereas female stocks are homozygous for the autosomal upstream activation sequence-regulated Aβ42 transgene. Both the male and female stocks are asymptomatic and can be propagated normally. However, crossing these flies produces female progeny that express Aβ42 in their CNS and display the disease phenotype (32).

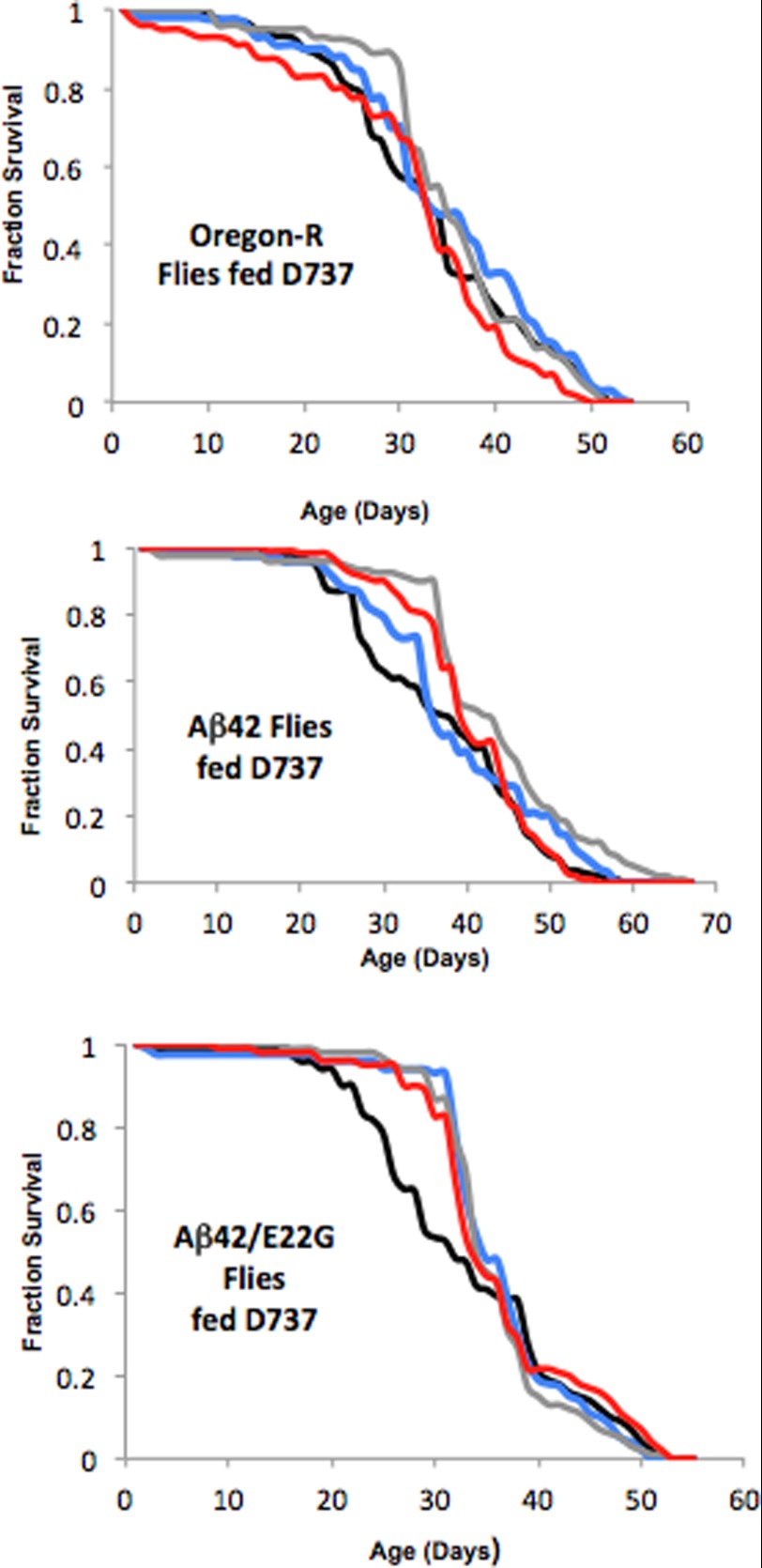

Prior to testing in transgenic flies, the possible toxicity of compound D737 was assessed in wild-type Oregon-R Drosophila. Males and females were mated in vials containing D737 to ensure that offspring would be exposed to D737 from the embryonic stage onward. Upon eclosion, 100 adult female virgins were placed in five vials (20 flies each) on fly food supplemented with D737 (or a DMSO control). Wild-type flies fed 2 or 20 μm D737 showed no significant change in life span, whereas 200 μm D737 caused a slight decrease in life span (Fig. 7a). Thus, 200 μm may be slightly toxic.

FIGURE 7.

Longevity of transgenic flies expressing Aβ42 is enhanced by D737. a, D737 did not affect wild-type (Oregon-R; black line) flies. b and c, flies expressing Aβ42 (a) and the Arctic mutant, Aβ42(E22G) (b), in their CNS (black lines) compared with flies fed 2 μm (blue lines), 20 μm (gray lines), and 200 μm (red lines) D737.

Next, we tested the effect of D737 on the transgenic flies. Female progeny expressing Aβ42 in their CNS were exposed to D737 from the embryonic stage onward as described above. We tested concentrations of 2, 20, and 200 μm and found that 20 μm D737 increased longevity considerably, with a median fly life span of 43 days (p = 0.007), compared with flies in the control group, with a median life span of 37 days (Fig. 7b). 200 μm D737 was slightly less effective, with a median life span of 41 days (p = 0.017). (As noted above, this may indicate that 200 μm D737 is slightly toxic.) To confirm the efficacy of D737, we performed a second independent trial using the most effective dose (20 μm). In this trial, flies fed D737 had a median life span that was 4 days longer compared with flies fed DMSO (p = 0.0038) (data not shown).

We then tested transgenic flies expressing the Arctic mutant, Aβ42(E22G). The median life span for untreated flies expressing Aβ42(E22G) was 30 days, whereas flies fed 2, 20, or 200 μm D737 had median life spans of 35, 34, and 34 days, respectively (p = 0.006, 0.002, and 0.01, respectively) (Fig. 7c). Thus, D737 is effective at lower concentrations and has a more dramatic impact on flies expressing the Arctic mutant than wild-type Aβ42.

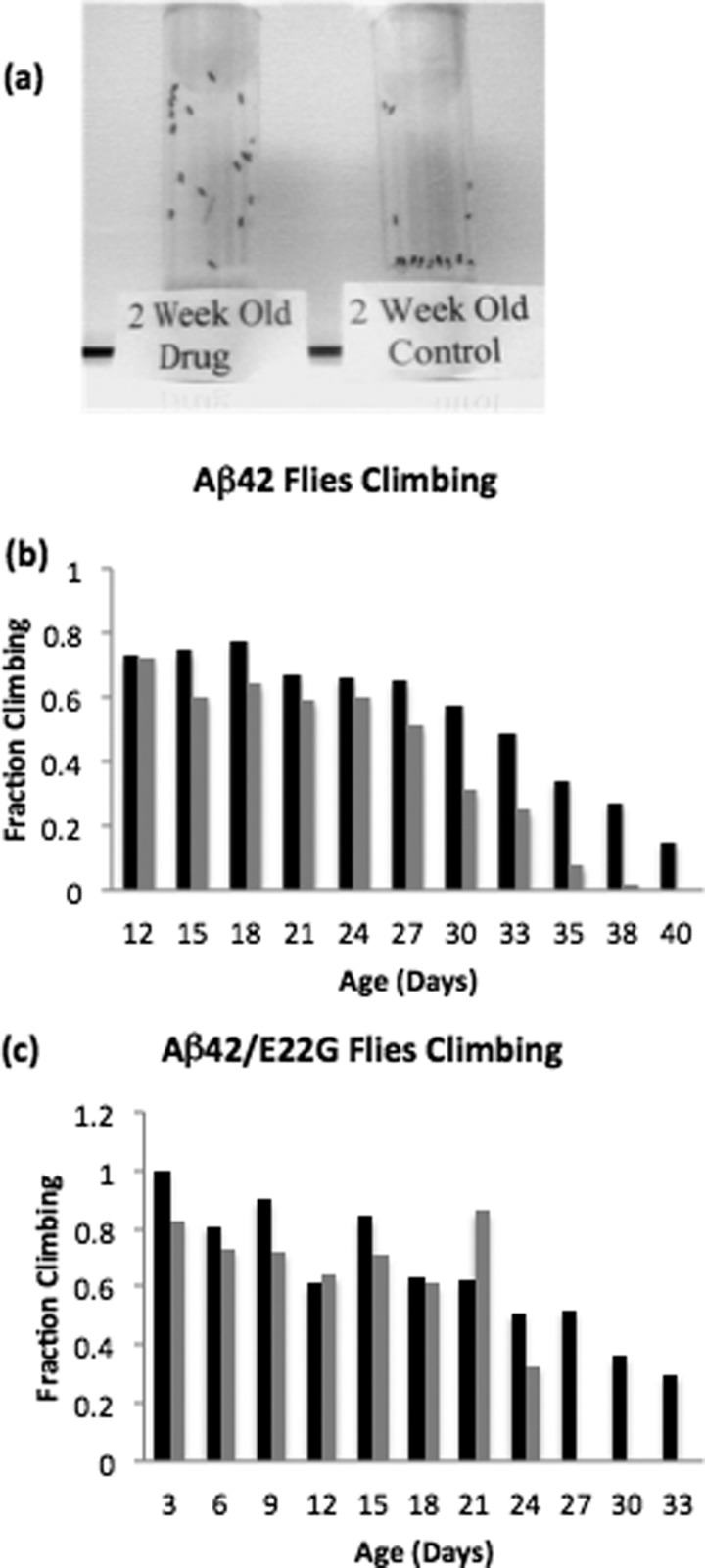

Although transgenic Alzheimer flies behave normally at eclosion, they eventually develop locomotive deficits. We assessed locomotive activity using a climbing assay described by Crowther et al. (36). 20 flies per vial were gently tapped to the bottom, and after 18 s, we recorded the number of flies at the top of vial. As shown in Fig. 8a, transgenic flies fed 20 μm D737 showed a dramatic improvement in climbing ability (see also supplemental Movie 1).

FIGURE 8.

a, improved locomotive ability of 2-week-old flies expressing Aβ42 in their CNS treated with 20 μm D737 versus the DMSO control. b, fraction of flies climbing as a function of time for Drosophila flies expressing Aβ42. Flies were fed DMSO (gray bars) or 20 μm D737 (black bars). c, similar to b for flies expressing the Aβ42(E22G) mutant. Assays using lower and higher concentrations of D737 are shown in supplemental Fig. 4.

The untreated transgenic flies showed a gradual decrease in locomotive ability from day 12 to complete failure of locomotive ability by day 39. Treatment with D737 improved locomotive ability dramatically. For example, at 38 days, only 6% of untreated flies continued to climb, whereas 34% of flies fed 20 μm D737 continued to climb (Fig. 8b). Flies expressing the Aβ42(E22G) mutant gradually lost locomotive ability from day 3 to day 24. By day 27, untreated Aβ42(E22G) transgenic flies completely lost their ability to climb. Treatment with D737 had a dramatic effect on these mutant flies: on day 27, 52% of those fed 20 μm D737 still climbed (Fig. 8c). (Improvement in locomotive ability by 2 and 200 μm D737 is shown in supplemental Fig. 4.) In summary, these results show that compound D737 significantly improves both the longevity and locomotive ability of transgenic Drosophila flies expressing either wild-type Aβ42 or Aβ42(E22G) in their CNS.

DISCUSSION

The high resolution structure of the exact molecular species responsible for Aβ42 toxicity is not known. Therefore, structure-based drug design is not possible, and high throughput screening remains the most powerful way to identify inhibitors of Aβ42 aggregation that may lead to therapeutics for AD. Given the growing body of evidence suggesting that soluble oligomers play a major role in neurodegeneration, it is important to utilize screens capable of identifying compounds that inhibit the formation of oligomers. Here, we have show that an inexpensive high throughput screen is effective in identifying compounds that not only inhibit Aβ aggregation but also reduce toxicity in vitro and in vivo. In particular, compound D737, isolated from this screen, inhibits Aβ42 aggregation, reduces the cytotoxicity of Aβ42, and diminishes the cellular accumulation of ROS. Most importantly, D737 leads to significant improvements in both life span and locomotive ability in a transgenic D. melanogaster model of AD.

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Segal (Tel Aviv University) for generously providing transgenic flies and for hosting A. F. M. in his laboratory. We also thank Stephanie Norton, Frank An, Jason Burbank, and Lynn VerPlank for assistance in scaling the GFP assay to a high throughput assay, data analysis, and subsequent selection of compounds.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant 5R21AG028462 (to M. H. H.) and the NCI Initiative for Chemical Genetics, National Institutes of Health, under Contract N01-CO-12400 and has been performed with the assistance of the Chemical Biology Platform of the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. This work was also supported by Award IIRG-08-89944 from the Alzheimer Association (to M. H. H.) and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to T. S.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–4 and Movie 1.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- Aβ

- amyloid β

- LMW

- low molecular weight

- HMW

- high molecular weight

- HTS

- high throughput screen

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- ThT

- thioflavin T

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- DCF

- dichlorofluorescein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alexandrescu A. (2005) Amyloid accomplices and enforcers. Protein Sci. 14, 1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clippingdale A. B., Wade J. D., Barrow C. J. (2001) The amyloid β peptide and its role in Alzheimer disease. J. Pept. Sci. 7, 227–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Selkoe D. J., Podlisny M. B. (2002) Deciphering the genetic basis of Alzheimer disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 3, 67–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Selkoe D. J, Schenk D. (2003) Alzheimer disease: molecular understanding predicts amyloid-based therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43, 545–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hardy J. A., Higgins G. A. (1992) Alzheimer disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256, 184–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Selkoe D. (2001) Alzheimer disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol. Rev. 81, 741–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Citron M. (2010) Alzheimer disease: strategies for disease modification. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 387–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tiraboschi P., Hansen L. A., Thal L. J., Corey-Bloom J. (2004) The importance of neuritic plaques and tangles to the development and evolution of AD. Neurology 62, 1984–1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Masters C. L., Simms G., Weinman N. A., Multhaup G., McDonald B. L., Beyreuther K. (1985) Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 4245–4249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hardy J., Allsop D. (1991) Amyloid deposition as the central event in the etiology of Alzheimer disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 12, 383–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hardy J., Selkoe D. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Walsh D. M., Selkoe D. J. (2007) Aβ oligomers–a decade of discovery. J. Neurochem. 101, 1172–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walsh D. M., Selkoe D. J. (2004) Oligomers on the brain: the emerging role of soluble protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Protein Pept. Lett. 11, 213–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Glabe C. (2008) Structural classification of toxic amyloid oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29639–29643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shi C., Zhao L., Zhu B., Li Q., Yew D. T., Yao Z., Xu J. (2009) Protective effects of Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) and its constituents quercetin and ginkgolide B against β-amyloid peptide-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 181, 115–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Necula M., Kayed R., Milton S., Glabe C. (2007) Small molecule inhibitors of aggregation indicate that amyloid β oligomerization and fibrillization pathways are independent and distinct. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 10311–10324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kayed R., Head E., Thompson J. L., McIntire T. M., Milton S. C., Cotman C. W., Glabe C. G. (2003) Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science 300, 486–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim W., Kim Y., Min J., Kim D. J., Chang Y. T., Hecht M. H. (2006) A high throughput screen for compounds that inhibit aggregation of the Alzheimer peptide. ACS Chem. Biol. 1, 461–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Waldo G. S., Standish B. M., Berendzen J., Terwilliger T. C. (1999) Rapid protein-folding assay using green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 17, 691–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Seiler K. P., George G. A., Happ M. P., Bodycombe N. E., Carrinski H. A., Norton S., Brudz S., Sullivan J. P., Muhlich J., Serrano M., Ferraiolo P., Tolliday N. J., Schreiber S. L., Clemons P. A. (2008) ChemBank: a small molecule screening and cheminformatics resource database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 351–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. LeVine H., 3rd (1993) Thioflavin T interaction with synthetic Alzheimer disease β-amyloid peptides: detection of amyloid aggregation in solution. Protein Sci. 2, 404–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johansson A. S., Berglind-Dehlin F., Karlsson G., Edwards K., Gellerfors P., Lannfelt L. (2006) Physiochemical characterization of the Alzheimer disease-related peptides Aβ1–42Arctic and A β1–42wt. FEBS J. 273, 2618–2630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee S., Fernandez E. J., Good T. A. (2007) Role of aggregation conditions in structure, stability, and toxicity of intermediates in the Aβ fibril formation pathway. Protein Sci. 16, 723–732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lambert M. P., Barlow A. K., Chromy B. A., Edwards C., Freed R., Liosatos M., Morgan T. E., Rozovsky I., Trommer B., Viola K. L., Wals P., Zhang C., Finch C. E., Krafft G. A., Klein W. L. (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Aβ1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6448–6453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cleary J. P., Walsh D. M., Hofmeister J. J., Shankar G. M., Kuskowski M. A., Selkoe D. J., Ashe K. H. (2005) Natural oligomers of the amyloid β protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barghorn S., Nimmrich V., Striebinger A., Krantz C., Keller P., Janson B., Bahr M., Schmidt M., Bitner R. S., Harlan J., Barlow E., Ebert U., Hillen H. (2005) Globular amyloid β peptide oligomer–a homogenous and stable neuropathological protein in Alzheimer disease. J. Neurochem. 95, 834–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mosmann T. (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mazza M., Capuano A., Bria P., Mazza S. (2006) Ginkgo biloba and donepezil: a comparison in the treatment of Alzheimer dementia in a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Eur. J. Neurol. 13, 981–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yao Z., Drieu K., Papadopoulos V. (2001) The Ginkgo biloba extract EGb761 rescues the PC12 neuronal cells from β-amyloid-induced cell death by inhibiting the formation of β-amyloid-derived diffusible neurotoxic ligands. Brain Res. 889, 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shaykhalishahi H., Yazdanparast R., Ha H. H., Chang Y. T. (2009) Inhibition of H2O2-induced neuroblastoma cell cytotoxicity by a triazine derivative, AA3E2. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 622, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yazdanparast R., Shaykhalishahi H. (2009) Protective effect of a triazine-derivative (AA3E2) on β-amyloid-induced damages in SK-N-MC cells. Toxicol. in Vitro 23, 1277–1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crowther D. C., Kinghorn K. J., Miranda E., Page R., Curry J. A., Duthie F. A., Gubb D. C., Lomas D. A. (2005) Intraneuronal Aβ, non-amyloid aggregates and neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of Alzheimer disease. Neuroscience 132, 123–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pandey U. B., Nichols C. D. (2011) Human disease models in Drosophila melanogaster and the role of the fly in therapeutic drug discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 411–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Iijima K., Chiang H. C., Hearn S. A., Hakker I., Gatt A., Shenton C., Granger L., Leung A., Iijima-Ando K., Zhong Y. (2008) Aβ42 mutants with different aggregation profiles induce distinct pathologies in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 3, e1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Luheshi L. M., Tartaglia G. G., Brorsson A. C., Pawar A. P., Watson I. E., Chiti F., Vendruscolo M., Lomas D. A., Dobson C. M., Crowther D. C. (2007) Systematic in vivo analysis of the intrinsic determinants of amyloid β pathogenicity. PLoS Biol. 5, e290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crowther D. C., Page R., Chandraratna D., Lomas D.A. (2006) A Drosophila model of Alzheimer disease. Methods Enzymol. 412, 234–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scherzer-Attali R., Pellarin R., Convertino M., Frydman-Marom A., Egoz-Matia N., Peled S., Levy-Sakin M., Shalev D. E., Caflisch A., Gazit E., Segal D. (2010) Complete phenotypic recovery of an Alzheimer disease model by a quinone-tryptophan hybrid aggregation inhibitor. PLoS ONE 5, e11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frydman-Marom A., Levin A., Farfara D., Benromano T., Scherzer-Attali R., Peled S., Vassar R., Segal D., Gazit E., Frenkel D., Ovadia M. (2011) Orally administrated cinnamon extract reduces β-amyloid oligomerization and corrects cognitive impairment in Alzheimer disease animal models. PLoS ONE 6, e16564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]