Abstract

Neuroenergetic models of synaptic transmission predicted that energy demand is highest for action potentials (APs) and postsynaptic ion fluxes, whereas the presynaptic contribution is rather small. Here, we addressed the question of energy consumption at Schaffer-collateral synapses. We monitored stimulus-induced changes in extracellular potassium, sodium, and calcium concentration while recording partial oxygen pressure (pO2) and NAD(P)H fluorescence. Blockade of postsynaptic receptors reduced ion fluxes as well as pO2 and NAD(P)H transients by ∼50%. Additional blockade of transmitter release further reduced Na+, K+, and pO2 transients by ∼30% without altering presynaptic APs, indicating considerable contribution of Ca2+-removal, transmitter and vesicle turnover to energy consumption.

Keywords: action potential, brain slice, electrophysiology, energy metabolism, evoked potentials, hippocampus

Introduction

Energy limitations determine the computational power and speed of neuronal systems.1 Therefore, it is of critical importance to identify the energy demand associated with processes involved in neuronal computing such as synaptic transmission and action potential (AP) firing. Theoretical calculations on the basis of current kinetics in squid giant axons suggested that APs and postsynaptic ion fluxes rather than presynaptic processes determine energy consumption.1, 2 More recently, energy efficient AP generation and conduction was described in hippocampal mossy fibers.3, 4, 5 Recalculating the energy need for APs suggests larger contribution of postsynaptic and presynaptic processes and transmitter uptake to the energy demand of synaptic transmission.6, 7 The authors predicted that in cerebral cortex, 50% of signaling associated energy is spent on restoration of ion fluxes at postsynaptic glutamate receptors, 21% is spent on APs, 20% on resting potentials, 5% and 4% on presynaptic transmitter release and transmitter recycling, respectively. However, such numbers have to be calculated or determined experimentally for each brain area in question as synaptic densities, receptor types, and ion channel expression differ for each particular signaling pathway.

Here, we sought to determine the contribution of pre- and postsynaptic processes to changes in energy metabolism associated with glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission at the hippocampal Schaffer-collateral synapse that represents one of the best-studied connections in the archicortex. We monitored stimulus-induced changes in extracellular potassium, sodium, and calcium concentrations ([K+]o, [Na+]o, [Ca2+]o) while recording tissue partial oxygen pressure (pO2) and metabolism-related NAD(P)H transients. The energy demand of each single component of synaptic transmission was identified by sequential blockade of postsynaptic receptors, voltage-gated Ca2+-channels and APs.

Materials and methods

Hippocampal Slices

Animal care was in accordance with the Helsinki declaration and institutional guidelines (as proved by the State Office of Health and Social Affairs Berlin, T0032/08, T0100/03) and experiments were carried out following the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments). Data were obtained from 73 brain slices (30 male wistar rats, 5 to 6 weeks). Animals were decapitated under isoflurane (3% V/V) anesthesia and horizontal hippocampal slices (400 μm) were prepared and transferred to an interface recording chamber. Slices were perfused with gassed (95% O2, 5% CO2) aCSF (artificial cerebrospinal fluid; containing in mM: 129 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 1.6 CaCl2, 1.8 MgCl2) at flow rates 1.5 mL/min or 5 mL/min for interface or submerged chambers, respectively. Microfluorimetric recordings were performed under submerged condition with reduced slice thickness (300 μm).

Electrophysiology and Oxygen Recordings

Recordings of field potentials (fp) and changes in [K+]o and [Ca2+]o or [Na+]o were performed in the stratum radiatum of CA1 with double-barreled ion-sensitive microelectrodes, manufactured and tested as previously described (Figure 1A8). The reference barrel was filled with 154 mM NaCl solution, the ion-sensitive barrel with ionophore cocktail (Potassium Ionophore I 60031, Calcium Ionophore I 21048, or Sodium Ionophore II 71178 all from Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) and 100 mM KCl, 100 mM CaCl2, or 150 mM NaCl, respectively. Intracellular recording from CA1 pyramidal cells were performed with sharp microelectrodes (resistance 60 to 90 MΩ) filled with 2.5 mM potassium-acetate in the interface chamber or with patch electrodes under submerged conditions. Whole cell patch recordings were carried out in visually identified CA1 pyramidal cells with a pipette solution containing in mM: 135 K-gluconate, 6 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP (pH 7.2, osmolarity 290 mOsm). EPSCs and IPSCs were separated by clamping the membrane potential to −80 and 0 mV, respectively. Patch clamp experiments were performed under identical conditions as used for NAD(P)H fluorescence recordings. The Clark-style oxygen sensor microelectrodes (tip: 10 μm; Unisense, Aarhus, Denmark) were polarized overnight and calibrated in aCSF saturated with 100% N2, 20% or 95% O2.9 The signal of the polarographic amplifier (Chemical Microsensor II; Diamond General Development) was recorded simultaneously with the signal of the ion-sensitive electrodes. Electrophysiological experiments were performed using CED 1401 interface and Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK) or with MultiClamp 700B amplifier and pClamp10 software (Axon CNS, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Field potential recordings were performed at a depth of 50 to 75 μm from the slice surface. Stimulus trains (20 Hz, 2 seconds duration, 80% of the intensity evoking the maximal fp) were applied to the stratum radiatum at 0.75 to 1 mm distance from the recording electrode every 4 minutes. Intracellular recordings revealed a short-term potentiation followed by depression of the excitatory postsynaptic potential amplitude (EPSP) during stimulus trains. Average EPSP amplitude was 101% of the initial EPSP of a sequence. In all, 20 Hz stimulation was chosen as it induced clearly measurable ion, pO2 and fluorescence transients without evoking long-term potentiation or depression of synaptic transmission as with high (100 Hz) or low (<5 Hz) frequency stimulation. To test stability of the signals, stimulation induced pO2 and K+ transients were followed for 100 minutes without any additional treatment (n=5; Figure 2D).

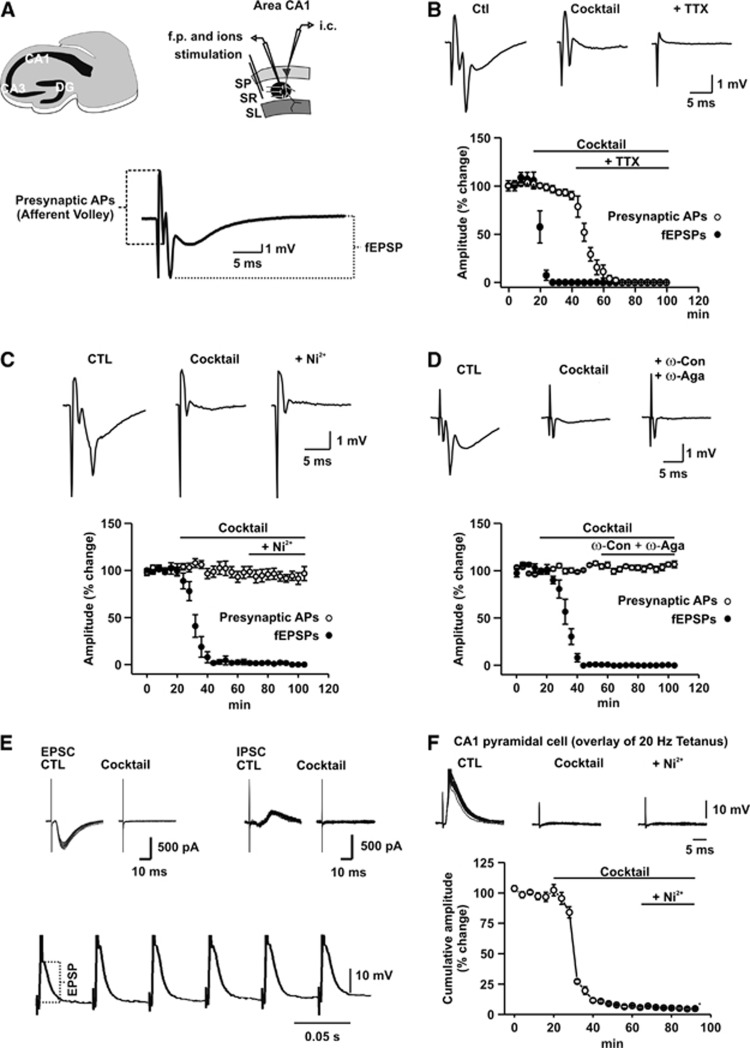

Figure 1.

Changes in field potential (fp) responses and excitatory postsynaptic potential amplitude (EPSPs) during sequential blockade of postsynaptic receptors, voltage-gated Ca2+-channels, and action potentials (APs). (A) Schematic representation of the recording design and stimulus-induced fp responses in the str. radiatum (SR) of CA1 (SP, stratum pyramidale and SL: stratum lacunosum moleculare). Presynaptic APs were represented by the afferent volley, the shortest latency component of the fp response. Postsynaptic responses including postsynaptic population spike and field EPSPs (fEPSP) were quantified by measuring the amplitude of the subsequent negative deflection of the fp response. (B) Effect of sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and APs on the different components of the fp response in percentage of the control (CTL). Note that the cocktail blocks fEPSP and postsynaptic APs completely within 20 minutes. Field potential is completely abolished in the presence of TTX, indicating that no direct activation of postsynaptic cells occurred. (C) Effect of sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and presynaptic Ca2+-entry by Ni2+ on the different components of the fp response in percentage of the control. Note that presynaptic APs remain unchanged in the presence of Ni2+. (D) Effect of sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and presynaptic Ca2+-entry by ω-Conotoxin MVIIC/ω-Agatoxin TK (ω-Con/ω-Aga) on the different components of the fp response in percentage of the control. Similarly to Ni2+ ω-Con/ω-Aga did not influence presynaptic APs as represented by the afferent volley. (E) Effect of glutamate and GABAA receptors on the EPSCs/IPSCs in CA1 pyramidal cell under submerged conditions. Overlay of EPSCs/IPSCs of a stimulus train aligned by the stimulation artifact (upper traces). Note the disappearance of synaptic components in the presence of the cocktail. First six pulses of stimulus train as recorded with a sharp electrode from a CA1 pyramidal cell under interface conditions (lower trace). Note a slight increase of the EPSP amplitude from the first to the second stimulus. (F) Overlay of EPSPs during sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and presynaptic Ca2+-entry by Ni2+. EPSP was almost completely inhibited by the cocktail, whereas subsequent application of Ni2+ did not cause a further reduction of the EPSP amplitude.

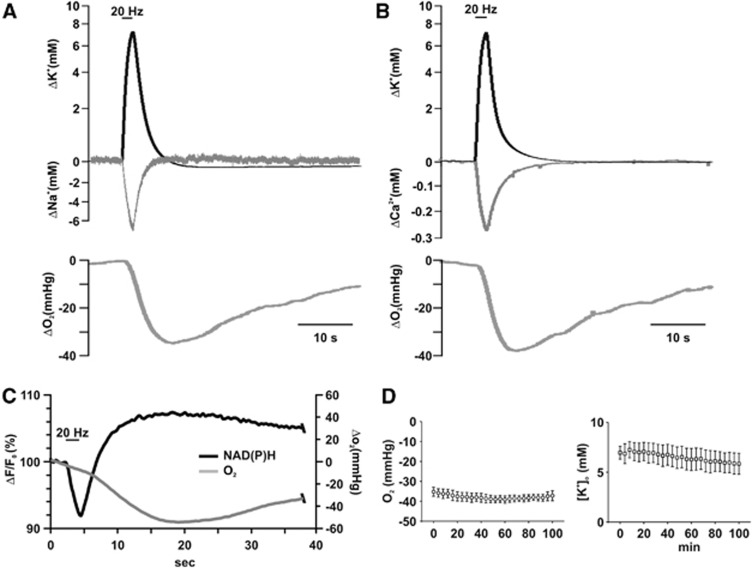

Figure 2.

Kinetics of stimulus-induced [K+]o, [Ca2+]o, [Na+]o, partial oxygen pressure (pO2), and NAD(P)H transients. (A) Simultaneously measured changes in [K+]o, [Na+]o, and pO2. The start of the decrease in pO2 is delayed as compared with the ion fluxes and the falling phase of the pO2 transient overlaps with the phase of recovery of ion transients. (B) Simultaneously measured changes in [K+]o, [Ca2+]o, and pO2. Although recovery of [Ca2+]o is slightly slower than that of [Na+]o, it still overlaps with the largest part of falling phase of pO2. (C) Simultaneous recording of pO2 and NAD(P)H fluorescence transients under submerged conditions. Decrease of the NAD(P)H fluorescence represents a shift to the oxidized, an increase in the fluorescence to the reduced form of NAD(P)H. pO2 as measured with the Clark-style oxygen electrode lags behind the changes in the fluorescence, suggesting that O2 diffusion in the tissue might alter the kinetics of pO2 transients. Note that NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio is increased during the whole period of enhanced O2 consumption. Stimulation lengths are indicated with the bars on the top of (A–C). (D) Amplitude of stimulus-induced pO2 and [K+]o transients did not change significantly over 100 minutes of repeated stimulation, indicating that neither synaptic facilitation nor synaptic depression occur with 20 Hz stimulation protocol.

Fluorescence Recordings

For recording of NAD(P)H fluorescence in the stratum radiatum of CA1, we used a modified confocal microscope (SP2 Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a cooled UV-LED (365 nm±5 nm, NCSU 033A, Nichia, Japan). Diode current was set to 15 to 18 mA giving rise to 47 μW under the × 63 objective (NA: 0.9). To minimize photobleaching, acquisition rate was kept low (2 Hz during stimulation and 0.5 Hz between stimulus trains). The fluorescence traces are shown as Δf/f0 where f0 is the average intensity taken from a period of 10 seconds before stimulation.

Pharmacology

AMPA/kainate, NMDA, and metabotropic glutamate receptors as well as GABAA receptors were blocked by a cocktail containing: 25 μM (or 50 μM) 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX), 50 μM (2R)-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (DL-APV), 150 μM (RS)-α-Methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG; Ascent Scientific, Bristol, UK) and 5 μM bicuculline methiodide (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany). Inhibitors of GABAB receptors were not applied that might lead to a slight underestimation of the energy need associated with postsynaptic ion fluxes. However, this cocktail readily reduced intracellular postsynaptic potentials/currents by >95% and prevented generation of postsynaptic APs (Figures 1E and 1F). NiCl2 (2.5 mM; Sigma) or ω-Agatoxin TK/ω-Conotoxin MVIIC (1 to 1 μM, in 0.1 mM albumin containing aCSF, Tocris, Eching Germany) and tetrodotoxin (1 μM, TTX; Ascent Scientific) were added to the cocktail in the corresponding experiments to block Ca2+- and Na+-channels, respectively.

Data Analysis

To test stability of the evoked responses, all experiments started with a control recording period (20 minutes) followed by application of the cocktail and subsequent application of either TTX, Ni2+, or ω-Agatoxin IVA/ω-Conotoxin MVIIC in addition to the cocktail. Stimulation was repeated during wash-in of the cocktail (40 to 60 minutes) until no further change in the amplitude of [K+]o transients occurred. Four stimuli were averaged for each experimental condition. Changes in ion concentrations and pO2 were calculated by using the modified Nernst equation and the pO2 calibration curves.8 Stimulus-induced fp responses were analyzed to monitor changes in presynaptic APs and postsysnaptic APs and EPSPs. The amplitude of the first, TTX-sensitive part (afferent volley) of the fp response was used to monitor changes in presynaptic APs, whereas the amplitude of the second, CNQX/DL-APV/MCPG/bicuculline-sensitive part of the fp response was used to determine changes in postsynaptic APs and field EPSPs (Figures 1A–1D). To quantify the block of glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission under submerged and interface conditions, cumulative amplitude of the intracellularly recorded EPSCs/IPSCs or EPSP responses were compared in the absence and in the presence of the cocktail (Figures 1E and 1F). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Within- and between-group differences were calculated using repeated measures analysis of variance including LSD post hoc test (for effects of consecutive block of neurotransmission, Ca2+- or Na+-channels) and independent variables t-test (for comparison of the effects of different CNQX concentrations, and different Ca2+-channel blockers; SPSS software package Version 18, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was considered at P≤0.05.

Results

Energy Demand Associated with Pre- and Postsynaptic Ion Fluxes

Electrical stimulation of hippocampal slices results in changes in energy metabolism as revealed by biphasic NAD(P)H fluorescence transients.10, 11 We applied pharmacology to dissect single components contributing to the enhanced energy consumption. Stimulus trains (20 Hz, 2 seconds) induced [K+]o, [Na+]o, and [Ca2+]o transients in the stratum radiatum of CA1 (Figures 2A and 2B). [K+]o transients remained stable over a period of 100 minutes when the slices were stimulated repeatedly every 4 minutes without any pharmacological intervention, indicating that neither potentiation nor suppression of the synaptic responses would interfere with the amplitude of the ion transients (Figure 2D). Blockade of the glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission and APs of postsynaptic cells by a cocktail containing DL-APV, CNQX, MCPG, and bicuculline methiodide led to a reduction of ion transients by 49.9%±2.1% ([Na+]o), 50.0%±6.0% ([Ca2+]o), and 44.0%±3.9% ([K+]o) (Figures 3A–3E, n=5, 13, 13). Taking into account that the vast majority of the active synapses during Schaffer-collateral stimulation is glutamatergic, we doubled the concentration of CNQX, but this did not lead to any further decrease in [K+]o transients, indicating a complete block at 25 μM CNQX. Analyzing the different components of the fp response associated with each single stimulus within a stimulus train revealed a >98% block of the late part of the fp associated with postsynaptic potential changes, whereas the afferent volley, representing presynaptic APs, remained unaltered in the presence of the cocktail (n=15, P=0.3, Figures 1B–1D). To exclude that electrical stimulation would directly activate neurons in the CA1, we applied TTX following the cocktail. Tetrodotoxin completely abolished fps and ion transients (Figures 3A–3C).

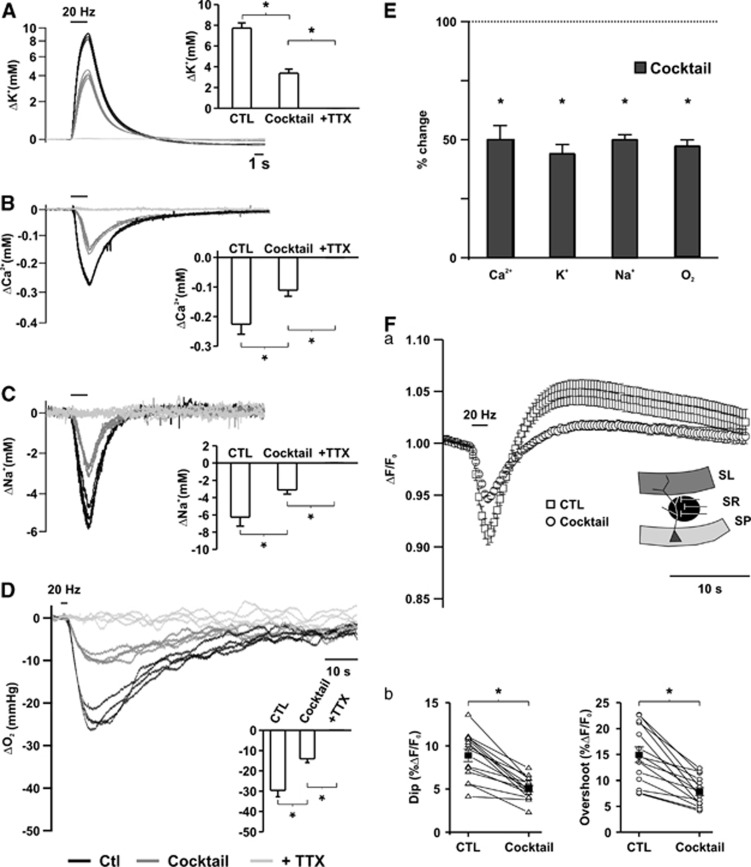

Figure 3.

Ion fluxes, oxygen consumption, and redox changes as created by pre- and postsynaptic processes. Changes in [K+]o (A), [Ca2+]o (B), [Na+]o (C), and partial oxygen pressure (pO2) (D) transients during sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and action potentials (APs). (E) Comparison of the changes in ion fluxes and oxygen consumption in percentage of control. Note that ∼50% of ion fluxes and pO2 changes were removed by inhibition of glutamate and GABAergic transmission. Asterisks mark statistical significance (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)). (Fa) Changes in biphasic NAD(P)H transients during blockade of glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission, the insert representing the area where the fluorescence was recorded. (Fb) Comparison of dip and overshoot components of NAD(P)H transients. Both components decreased equally in the presence of the cocktail.

Stimulus trains led to a decrease in tissue pO2 by 33.8±2.4 mm Hg (n=13, Figures 2A–2C), indicating enhancement of oxidative metabolism.8, 9 Stimulus-induced pO2 transients remained stable in the absence of pharmacological treatment over 100 minutes (Figure 2D). Comparable electrical stimulation induced biphasic transients in NAD(P)H fluorescence, with an initial dip (9.0%±0.6%), representing NAD(P)H oxidation, followed by an overshoot (15.8%±1.2%) corresponding to an increase in NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio (n=16). The initial dip of NAD(P)H transients preceded the negative peak of pO2 and oxygen consumption was enhanced during the whole duration of the overshoot (Figure 2C). Similarly, pO2 decreased during the whole duration of the [K+]o, [Na+]o, and [Ca2+]o transients reaching its peak following reconstitution of the transmembrane ion gradients. Recovery to baseline outlasted the ion transients by tens of seconds (Figures 2A and 2B).

Subsequent blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors decreased pO2 transients by 52.7%±2.6% (Figure 3, DE, n=13). Again, increasing CNQX concentration did not cause further decrease in pO2 transients. Also, both components of the biphasic NAD(P)H fluorescent transients decreased by 60.3%±3.7% and 53.4%±4.3% for the dip and overshoot, respectively (Figure 3F). Whole cell patch clamp recordings of CA1 pyramidal cells under submerged conditions revealed that both EPSCs and IPSCs were completely abolished at the time point of fluorescence recordings (n=6; Figure 1E).

Consequently, the ∼50% decrease in pO2 and NAD(P)H transients in the presence of the cocktail indicate that postsynaptic potentials and postsynaptic APs correspond to about 50% of the stimulus-induced changes in energy metabolism.

Energy Demand Associated with Presynaptic Processes of Synaptic Transmission

Presynaptic AP, presynaptic Ca2+-clearance, transmitter uptake, and vesicle recycling/refilling contribute to the remaining energy demand following blockade of postsynaptic ion fluxes. Preventing vesicle release allows for differentiation between the contribution of presynaptic APs and all other processes to energy consumption. In the presence of the nonselective blocker of presynaptic voltage-gated Ca2+-channels (Ni2+, 2.5 mM), [Ca2+]o transients were almost completely blocked (Figures 4A–4C; n=7), whereas presynaptic APs were unaltered (P=0.3, n=10; Figure 1C). In spite of intact presynaptic APs, stimulus-induced [K+]o and [Na+]o transients were significantly decreased (to 13.2%±1.6% and 24.6%±3.9% of the control for [K+]o and [Na+]o, n=13 and 6, respectively; Figure 4E) as compared with the values in the presence of the inhibitor cocktail (P<0.05 for all ions). Intracellular recordings of CA1 pyramidal cells (n=5) revealed that the cocktail massively decreased postsynaptic potentials (20.8±0.5 mV versus 1.65±0.3 mV, P<0.01) and blocked postsynaptic APs (Figure 1F). Subsequent application of Ni2+ caused only a slight, nonsignificant decrease in the remaining postsynaptic potentials (1.65±0.3 mV versus 1.0±0.2, P=0.06). Consequently, the additional ∼30% decrease in extracellular ion transients upon application of cocktail plus Ni2+ corresponds to ion fluxes associated with transmitter uptake and presynaptic Ca2+-clearance.

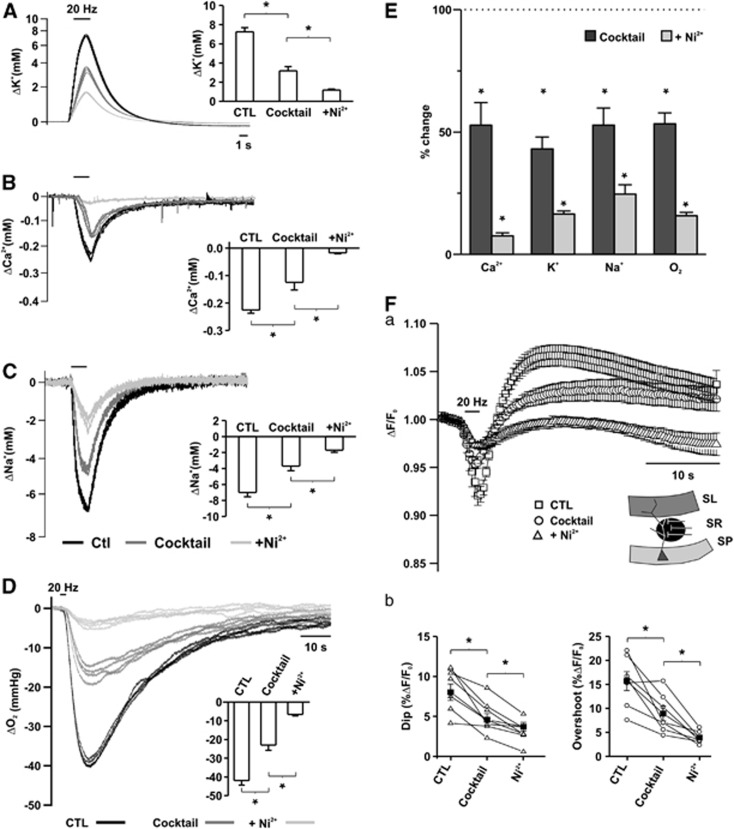

Figure 4.

Ion fluxes, oxygen consumption, and redox changes as created by presynaptic action potentials (APs) and transmitter release linked processes. Changes in [K+]o (A), [Ca2+]o (B), [Na+]o (C), and partial oxygen pressure (pO2) (D) transients during sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and vesicle release by Ni2+. (E) Comparison of the changes in ion fluxes and oxygen consumption in percentage of control. Note that ∼50% of ion fluxes and pO2 changes were removed by inhibition of glutamate and GABAergic transmission and Ni2+ further decreased all ion and pO2 transients by ∼30%, in spite of the unaltered presynaptic APs. Asterisks mark statistical significance (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)). (Fa) Changes in biphasic NAD(P)H transients during blockade of glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission and vesicle release by Ni2+. (Fb) Comparison of dip and overshoot components of NAD(P)H transients. Both components were further decreased in the presence of Ni2+.

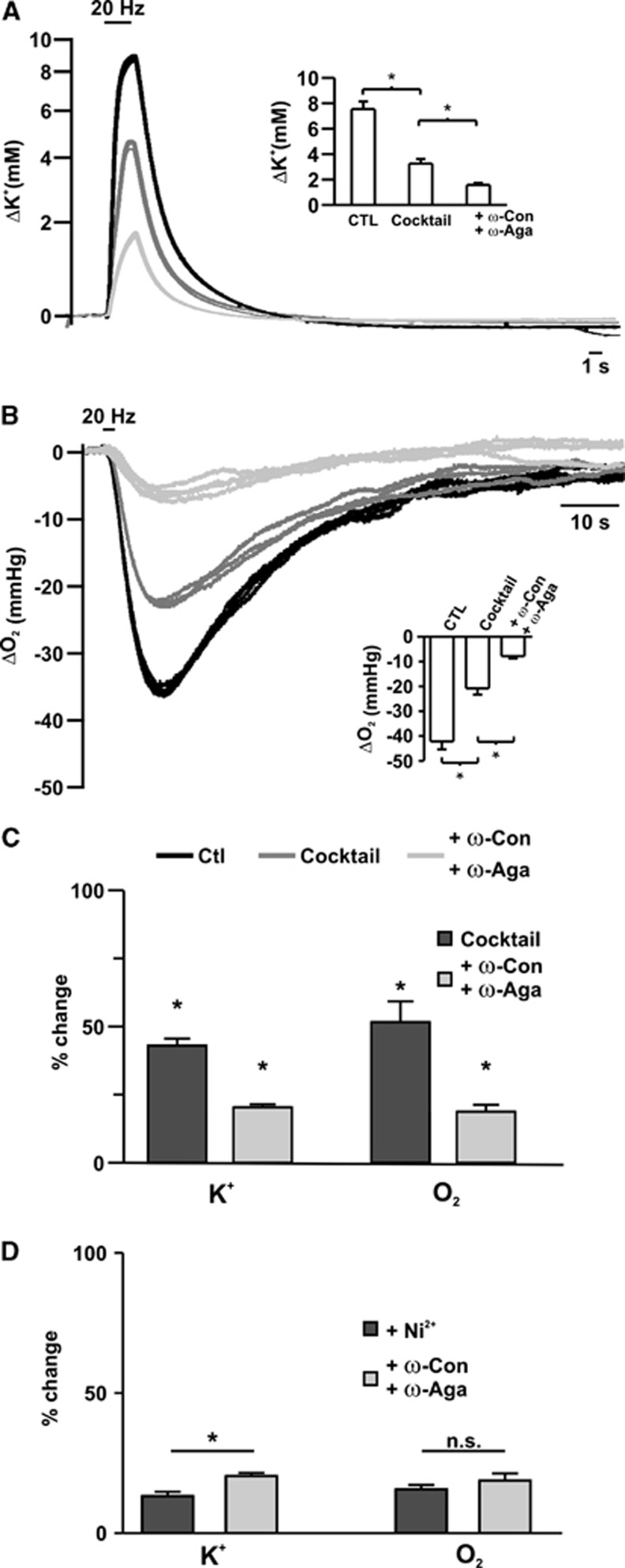

Ni2+ also reduced stimulus-induced changes in tissue pO2 and NAD(P)H fluorescence (pO2, to 15.6%±1.7% of control, NAD(P)H dip: 36.6%±6.5%, overshoot: 26.7%±3.6% of control; Figures 4D–4F; n=7). To exclude that Ni2+ interferes with presynaptic AP generation, the experiments were repeated by using specific inhibitors of voltage-gated Ca2+-channels (combination of ω-Agatoxin TK/ω-Conotoxin MVIIC; n=5). In this set of experiments, [K+]o and pO2 transients were decreased to 43.0%±2.6% and 51.62%±7.8 in the presence of the cocktail. Consecutive application of the toxins led to a further reduction (20.3%±1.1% and 18.8%±2.5%) in [K+]o and pO2 transients, respectively (Figures 5A–5C). There were no significant differences between the stimulus-induced [K+]o and pO2 transients in the two groups in the presence of the cocktail (44.0%±3.9% versus 43.0%±2.6% [K+]o, 52.7%±2.6% versus 51.63%±7.8 pO2). Ni2+ exerted a slightly larger effect on the [K+]o transients than ω-Agatoxin TK/ω-Conotoxin MVIIC (13.2%±1.6% versus 20.3%±1.1% P=0.004 for Ni2+ versus toxins, respectively). However, changes in pO2 were not significantly different (Figure 5D; 15.6%±1.7% versus 18.8%±2.5%, P=0.2 for Ni2+ versus toxins, respectively). Thus, Na+ and K+ fluxes associated with Ca2+-clearance and transmitter uptake were similar to the fluxes occurring during presynaptic APs, and the reduction in pO2 and NAD(P)H transients during blockade of vesicle release were comparable to the percentual decrease in Na+ and K+ transients.

Figure 5.

Changes in stimulus-induced [K+]o and partial oxygen pressure (pO2) transients during sequential blockade of synaptic transmission and presynaptic Ca2+-entry. Changes in [K+]o (A) and pO2 (B) transients during sequential blockade of glutamate and GABAA receptors and vesicle release by ω-Conotoxin MVIIC/ω-Agatoxin TK (ω-Con/ω-Aga). (C) Comparison of the changes in [K+]o fluxes and oxygen consumption in percentage of control. ω-Con/ω-Aga decreased [K+]o and pO2 transients by about an additional 30%. Asterisks mark statistical significance (repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA)). (D) Comparison of the effects of Ni2+ and ω-Con/ω-Aga on [K+]o and pO2 transients. Although Ni2+ had a significantly larger effect on the [K+]o transients, the reduction in pO2 transients was not different between Ni2+ and ω-Con/ω-Aga-treated groups (Student's t-test).

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that presynaptic processes, that is, Ca2+-clearance, transmitter uptake and vesicle recycling/refilling have similar contribution to ion fluxes and energy demand of synaptic transmission at the Schaffer-collateral synapse as presynaptic APs.

About 50% of the stimulus-induced ion fluxes were attributable to postsynaptic potentials and AP generation in postsynaptic target cells, as blockade of glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission decreased K+, Na+, and Ca2+ transients by this value. As restoration of transmembrane ion gradients is coupled to enhancement of energy metabolism, stimulus-induced pO2 and NAD(P)H fluorescence transients were also reduced by almost the same amount following blockade of the glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission. Changes in pO2 and NAD(P)H to NAD(P)+ ratio are generally accepted as interdependent indicators reporting different aspects of energy metabolism. While pO2 in slice preparation is predominantly influenced by the rate of oxidative phosphorylation, NAD(P)H fluorescence changes merely represent a shift in the balance of metabolic flux of electrons through these cofactor molecules. The advantage of monitoring NAD(P)H is that changes in fluorescence are an immediate measure of energy metabolism, whereas the kinetics of the pO2 signal is altered by oxygen diffusion within the tissue. The fluorescence dip indicating enhanced NAD(P)H oxidation preceded the negative peak of pO2 corresponding to fast activation of oxidative phosphorylation. Subsequent NAD(P)H fluorescence overshoot outlasted the whole period of pO2 decrease, suggesting lasting activation of glycolysis and/or mitochondrial dehydrogenases, in the presence of increased oxygen consumption.10, 11, 12, 13 The recovery of the extracellular ion fluxes overlapped with the first falling phase of pO2. Oxygen levels recovered slowly to the baseline after transmembrane ion gradients have been already restored. Tissue pO2 at a certain distance from the slice surface always represents a balance between delivery by diffusion and removal by oxidative metabolism. Thus, the absolute amplitude of oxygen consumption might be underestimated by the magnitude of O2 delivery. However, this does not apply to the relative reduction of the pO2 transients as diffusion ways did not differ in the presence or absence of the cocktail.

Blockade of Ca2+-channels by Ni2+ and subsequent inhibition of vesicle release led to further decrease in energy metabolism as revealed by pO2 and NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+ ratio. By using specific blockers of Ca2+-channels, we found similar reductions of stimulus-induced pO2 transients, excluding the possibility that Ni2+ would interact with presynaptic AP generation due to alteration of surface charge screening. Also, stimulus-induced [Na+]o and [K+]o transients decreased, suggesting involvement of glutamate transporters and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) in signaling associated ion fluxes. Na+ and K+ fluxes associated with Ca2+-clearance and transmitter uptake in the stratum radiatum were in the same range as fluxes generated by presynaptic AP, suggesting high density of presynaptic endings per average axonal length within the recorded area.

In a previous study, we found that ∼75% of the stimulus-induced intracellular Ca2+ transients in the stratum radiatum represent presynaptic Ca2+-influx.14 Rapid Ca2+-extrusion requires ATP either directly (plasmalemmal or endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases) or indirectly by using ion gradients as driving force (NCX, CaH exchanger).15 Uptake of transmitters16, 17 and synaptic vesicle recycling and refilling2 are also energy demanding processes leading to an increase in both astrocytic and neuronal energy metabolism. Unfortunately, blocking glutamate uptake by DL-threo-β-Benzyloxyaspartic acid (TBOA) resulted in massive extracellular glutamate accumulation during the stimulus train, leading to removal of the competitive inhibitors CNQX/DL-APV (not shown). At present, we cannot determine the relative contribution of transmitter uptake/vesicle cycling to the energy demand of synaptic transmission at the Schaffer-collaterals.

Distribution of energy consumption between pre- and postsynaptic structures might be different depending on the type of activity (stimulation frequency and intensity) and on the synaptic pathway in question. In contrast to the Schaffer-collateral synapses, in the cerebellum synaptic activity-dependent changes in energy metabolism were markedly suppressed by CNQX, suggesting predominant postsynaptic participation.18

At the dentate gyrus-CA3 synapse increasing stimulus length (>20 seconds) led to a decrease in the efficacy of synaptic transmission.8 Under such conditions, the contribution of the presynapse would be overestimated. In all, 20 Hz stimulation of the Schaffer-collaterals is expected to induce an increase in EPSPs amplitude.19 In our hands, EPSP facilitation reached a peak of about 30% at the third–fifth stimulus followed by a slow decline to ∼87% of the initial value. Average EPSP amplitude was 101% of the initial EPSP. Consequently, short-term changes in the synaptic strength did not influence the estimated presynaptic contribution to energy demand.

The present data represent dynamic changes in energy metabolism associated with synaptic transmission without taking into account interregional, cell type, and pathway-specific differences in energetic costs of resting potential, housekeeping protein syntheses etc.1, 2, 6, 7, 20 In terms of ATP use, calculated expenditure for the cortex were 50% on postsynaptic potentials, 21% on APs, 20% on resting potentials, and 9% on presynaptic processes.7 When the costs for resting potentials are not taken into account, these values renormalize to 62.5%, 26.25%, and 11.25% for postsynaptic processes, APs, and presynaptic processes, respectively. In our experiments, about 18% of the oxygen used was spent on presynaptic APs and about 30% on presynaptic process other than APs. However, it is very speculative—even ignoring the contribution of glycolysis—to compare ∼11% of the energy budget as calculated for ATP with the ∼30% of oxygen consumption, as we do not know the respiratory coupling ratio in brain slices. We have shown previously that the same ion movements and consequently the same amount of pump activity can induce different pO2 transients depending on the absolute tissue pO2.8 At high tissue pO2 (95%) respiration might become partially uncoupled making exact calculation of ATP production per μM oxygen extremely difficult.21 Nevertheless, our data indicate a considerable contribution of presynaptic processes to energy demand of synaptic transmission. This might explain the critical dependence of fast spiking interneuron activity on oxidative metabolism,9 despite the fact that energy demand of APs is close to the theoretical minimum.3, 5, 22

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the grants Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 618 and SFB TR-3, and by the Hertie-Foundation and Excellence Cluster NeuroCure.

References

- Attwell D, Gibb A. Neuroenergetics and the kinetic design of excitatory synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:841–849. doi: 10.1038/nrn1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1133–1145. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Roth A, Geiger JR. Energy-efficient action potentials in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science. 2009;325:1405–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1174331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BC, Bean BP. Sodium entry during action potentials of mammalian neurons: incomplete inactivation and reduced metabolic efficiency in fast-spiking neurons. Neuron. 2009;64:898–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Hieber C, Bischofberger J. Fast sodium channel gating supports localized and efficient axonal action potential initiation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10233–10242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6335-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JJ, Attwell D. The energetics of CNS white matter. J Neurosci. 2012;32:356–371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3430-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth C, Gleeson P, Attwell D. Updated energy budgets for neural computation in the neocortex and cerebellum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1222–1232. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huchzermeyer C, Albus K, Gabriel HJ, Otáhal J, Taubenberger N, Heinemann U, Kovács R, Kann O. Gamma oscillations and spontaneous network activity in the hippocampus are highly sensitive to decreases in pO2 and concomitant changes in mitochondrial redox state. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1153–1162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4105-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann O, Huchzermeyer C, Kovács R, Wirtz S, Schuelke M. Gamma oscillations in the hippocampus require high complex I gene expression and strong functional performance of mitochondria. Brain. 2011;134:345–358. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen MR. Ca2+-dependent changes in the mitochondrial energetics in single dissociated mouse sensory neurons. Biochem J. 1992;283:41–50. doi: 10.1042/bj2830041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan AM, Connor JA, Shuttleworth CW. NAD(P)H fluorescence transients after synaptic activity in brain slices: predominant role of mitochondrial function. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1389–1406. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasischke KA, Vishwasrao HD, Fisher PJ, Zipfel WR, Webb WW. Neural activity triggers neuronal oxidative metabolism followed by astrocytic glycolysis. Science. 2004;305:99–103. doi: 10.1126/science.1096485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan AM, Connor JA, Shuttleworth CW. Modulation of the amplitude of NAD(P)H fluorescence transients after synaptic stimulation. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:3233–3243. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ul Haq R, Liotta A, Kovács R, Rösler A, Jarosch MJ, Heinemann U, Behrens CJ. Adrenergic modulation of sharp wave-ripple activity in rat hippocampal slices. Hippocampus. 2012;22:516–533. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivannikov MV, Sugimori M, Llinás RR. Calcium clearance and its energy requirements in cerebellar neurons. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatton JY, Marquet P, Magistretti PJ. A quantitative analysis of L-glutamate-regulated Na+ dynamics in mouse cortical astrocytes: implications for cellular bioenergetics. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3843–3853. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azarias G, Perreten H, Lengacher S, Poburko D, Demaurex N, Magistretti PJ, Chatton JY. Glutamate transport decreases mitochondrial pH and modulates oxidative metabolism in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3550–3559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4378-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caesar K, Hashemi P, Douhou A, Bonvento G, Boutelle MG, Walls AB, Lauritzen M. Glutamate receptor-dependent increments in lactate, glucose and oxygen metabolism evoked in rat cerebellum in vivo. J Physiol. 2008;586:1337–1349. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott LF, Regehr WG. Synaptic computation. Nature. 2004;431:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nature03010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth C, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Attwell D. The energy use associated with neural computation in the cerebellum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:403–414. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski AJ, de Souza-Pinto NC, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;47:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenstaub A, Otte S, Callaway E, Sejnowski TJ. Metabolic cost as a unifying principle governing neuronal biophysics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;107:12329–12334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914886107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]