Abstract

The orexin/hypocretin (Orx/Hcrt) system has long been considered to regulate a wide range of physiological processes, including feeding, energy metabolism, and arousal. More recently, concordant observations have demonstrated an important role for these peptides in the reinforcing properties of most drugs of abuse. Orx/Hcrt neurons arise in the lateral hypothalamus (LH) and project to all brain structures implicated in the regulation of arousal, stress, and reward. Although Orx/Hcrt neurons have been shown to massively project to the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT), only recent evidence suggested that the PVT may be a key relay of Orx/Hcrt-coded reward-related communication between the LH and both the ventral and dorsal striatum. While this thalamic region was not thought to be part of the “drug addiction circuitry,” an increasing amount of evidence demonstrated that the PVT—particularly PVT Orx/Hcrt transmission—was implicated in the modulation of reward function in general and several aspects of drug-directed behaviors in particular. The present review discusses recent findings that suggest that maladaptive recruitment of PVT Orx/Hcrt signaling by drugs of abuse may promote persistent compulsive drug-seeking behavior following a period of protracted abstinence and as such may represent a relevant target for understanding the long-term vulnerability to drug relapse after withdrawal.

Keywords: paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus, orexin, hypocretin, drug-seeking behavior, natural reward

Introduction

Drug addiction is a chronically relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use (O'Brien and McLellan, 1996; Leshner, 1997; O'Brien et al., 1998; McLellan et al., 2000). Advances have been made in elucidating the neurocircuitry that mediates craving and drug seeking. Functional brain imaging in humans (e.g., Miller and Goldsmith, 2001; Goldstein and Volkow, 2002; Daglish and Nutt, 2003) and brain site-specific manipulations in animals (e.g., Everitt et al., 2001; Cardinal et al., 2002; See, 2002; Weiss, 2005) implicate interconnected cortical and limbic brain regions in response to drug cue-, drug priming-, and stress-induced reinstatement. Major components of this circuitry include the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), basolateral amygdala (BLA), central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), hippocampus, nucleus accumbens (NAC), and, more recently, dorsal striatum, which is thought to participate in consolidating stimulus-response habits via the engagement of corticostriatal loops (Everitt et al., 2001; McFarland and Kalivas, 2001; Ito et al., 2002; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Belin and Everitt, 2008; Steketee and Kalivas, 2011). However, unclear is what differentiates neural signaling related to normal appetitive behavior vs. compulsive behavior that results from long-term drug exposure. There is an overlap between the brain regions implicated in the processing of natural rewards and drugs of abuse, and it is thought that neural circuitry encoded for natural rewards is usurped by drugs of abuse. Neuroplasticity within this neural circuitry is believed to be responsible for the maladaptive (compulsive) behavior characteristic of addiction (Kelley and Berridge, 2002; Aston-Jones and Harris, 2004; Kalivas and O'Brien, 2008; Wanat et al., 2009), which may account for the interindividual vulnerability to drug abuse.

Recruitment of the Orx/Hcrt system by drugs of abuse

About 10 years ago, the orexin/hypocretin (Orx/Hcrt) system, already known to regulate a wide range of physiological processes, was shown to be recruited by drugs of abuse. Indeed, orexin A (Orx-A or hypocretin-1 [Hcrt-1]) and orexin B (Orx-B or hypocretin-2 [Hcrt-2]) were initially considered hypothalamic neuropeptides that regulate feeding, energy metabolism (Sakurai et al., 1998; Edwards et al., 1999; Haynes et al., 2000, 2002; Willie et al., 2001; Teske et al., 2010), and arousal (Sutcliffe and de Lecea, 2002; Taheri et al., 2002). Among the two Orx/Hcrt receptors identified, Hcrt-r1 binds to Orx-A/Hcrt-1 with 20–30 nM affinity but has much lower affinity (10–1000-fold lower) for Orx-B/Hcrt-2, and Hcrt-r2 binds to both peptides with similar affinity (in the 40 nM range; Sakurai et al., 1998; Ammoun et al., 2003; Scammell and Winrow, 2011). Orx/Hcrt cell bodies are essentially found in the lateral hypothalamus (LH), a brain region long associated with reward and motivation (for review, see DiLeone et al., 2003), perifornical hypothalamus (PFA), and dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH). Hypothalamic Orx/Hcrt neurons project to brainstem nuclei where they are considered to play a major role in the regulation of arousal and modulation of stress responses (Baldo et al., 2003; Winsky-Sommerer et al., 2004). They also project to the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT), NAC shell (NACsh), ventral pallidum (VP), ventral tegmental area (VTA), CeA, and BNST (Peyron et al., 1998; Baldo et al., 2003). A past conjecture suggested a dichotomy in Orx/Hcrt function, with Orx/Hcrt neurons in the LH regulating reward processes and Orx/Hcrt neurons in the PFA and DMH being mostly involved in the regulation of arousal and stress responses (Harris and Aston-Jones, 2006). However, recent evidence opposes this interpretation because similar patterns of Fos-positive Orx/Hcrt cells were observed in both the PFA/LH and DMH in rats exposed to contextual stimuli previously paired with ethanol availability (Dayas et al., 2008). Furthermore, medial and lateral Orx/Hcrt cells were shown to project to both the locus coeruleus and VTA, confirming that convergent projections from different Orx/Hcrt populations to these two brain areas may strengthen the temporal association between stress, arousal, and reward-seeking, thus optimizing goal-oriented behavioral strategies (Calipari and Espana, 2012; Gonzalez et al., 2012).

In addition to their involvement in the regulation of natural rewards, recent evidence showed that hypothalamic Orx/Hcrt neurons played a significant role in the modulation of reward function and, particularly, drug-directed behaviors (Harris et al., 2005). Hypothalamic Orx/Hcrt neurons become activated by stimuli associated with food, morphine, cocaine, and ethanol (Harris et al., 2005; Dayas et al., 2008; Martin-Fardon et al., 2010; Jupp et al., 2011). Similarly, the expression of conditioned place preference induced not only by food but also by morphine and cocaine is associated with activation of Orx/Hcrt neurons in the LH (Harris et al., 2005) likely due to the stimulation of LH Orx/Hcrt by rostral lateral septum afferents (Sartor and Aston-Jones, 2012). Consistent with these observations, intra-VTA microinjection of Orx-A produces a renewal of morphine-induced conditioned place preference, whereas administration of the Hcrt-r1 antagonist N-(2-methyl-6-benzoxazolyl)-N′-1,5-n-aphthyridin-4-yl urea (SB334867) decreases the expression of morphine-induced conditioned place preference (Harris et al., 2005). SB334867 also blocks the acquisition of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization and potentiation of excitatory currents induced by cocaine in VTA dopamine neurons (Borgland et al., 2006). Intra-VTA administration of SB334867 reduces the motivation to self-administer cocaine and attenuates the cocaine-induced enhancement of dopamine signaling in the NAC (Espana et al., 2010). Blockade of Hcrt-r1 decreases ethanol (Lawrence et al., 2006) and nicotine (Hollander et al., 2008) self-administration, inhibits cue-induced reinstatement of ethanol (Lawrence et al., 2006) and cocaine (Smith et al., 2010) seeking, and attenuates stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine and ethanol seeking (Boutrel et al., 2005; Richards et al., 2008).

Thus, behavioral and functional evidence indicates a role for Orx/Hcrt signaling in the motivational effects of cocaine and other drugs of abuse (Borgland et al., 2006; Bonci and Borgland, 2009; Thompson and Borgland, 2011), but questions remain about what differentiates Orx/Hcrt signaling related to normal appetitive behavior vs. compulsive behavior that results from long-term drug exposure.

Differential recruitment of the Orx/Hcrt system by drugs of abuse and natural rewards

One hypothesis concerning the control of drug-seeking behavior is that the neural circuits that mediate these effects are common motivational circuits that are more robustly activated by drug-related stimuli and not specific to addiction-related events. This activation that normally governs responding for natural rewards creates new motivational states or tilts processes that normally govern responding for natural rewards toward drug-directed behavior (Kelley and Berridge, 2002). Considered to orchestrate the appropriate levels of alertness required for the elaboration and execution of goal-oriented behaviors, Orx/Hcrt is one legitimate candidate for further investigating how a system normally involved in the regulation of motivation and arousal may trigger a pathological state that elicits compulsive craving and relapse to drug seeking (Boutrel et al., 2010).

Evidence has accumulated that the Orx/Hcrt system is, in fact, more strongly engaged by drugs of abuse compared with natural non-drug reinforcers. For example, it has been shown that SB-334867 treatment significantly reduced responding for ethanol but not sucrose under a progressive-ratio schedule of reinforcement (Jupp et al., 2011). An even more striking observation was that, although the stimuli conditioned to cocaine, ethanol, and a conventional reinforcer were shown to equally elicit reinstatement, SB334867 treatment selectively reversed conditioned reinstatement induced by a cocaine- or ethanol-related stimulus but had no effects on the same stimulus conditioned to a conventional reinforcer (sweetened condensed milk [SCM] or SuperSac [3%/0.125%, w/v, glucose/saccharin]; Martin-Fardon and Weiss, 2009, 2012; Martin-Fardon et al., 2010).

The pharmacological and neural mapping data are difficult to reconcile with the role of the Orx/Hcrt system in behavior motivated by food (i.e., a natural reward) and its more recently discovered role in drug reward. One hypothesis concerning the control of drug-seeking behavior is that the neural circuits that mediate the effects of drug cues are not specific to addiction-related events but rather are common motivational circuits that are more robustly activated by drug-related stimuli. This activation will create new motivational states or tilt processes that normally govern responding for natural rewards toward drug-directed behavior (Kelley and Berridge, 2002). Drugs of abuse may produce this effect by neuroadaptively altering the neural systems that regulate motivation directed toward natural rewards. Evidence of drug-induced dysregulation of the Orx/Hcrt system exists for alcohol. For example, prepro-orexin mRNA is up-regulated in the LH in inbred alcohol-preferring (iP) rats following chronic ethanol consumption (Lawrence et al., 2006). A possibility derived from this hypothesis is that the Orx/Hcrt system may, over the course of repeated drug use, acquire a preferential role in mediating the effects of stimuli conditioned to drugs of abuse vs. natural rewards. Consequently, one explanation for the preferential role of SB334867 in conditioned reinstatement for drugs vs. non-drugs could be that drugs neuroadaptively alter the neural systems that regulate motivation normally directed toward natural rewards that is revealed by pharmacological (e.g., SB334867) manipulations.

Maladaptive recruitment of the Orx/Hcrt system by drugs of abuse is also suggested by findings that described neuroadaptive changes within the VTA. For example, voluntary cocaine and natural reward self-administration induces a common, short-lasting neuroadaptation in VTA dopaminergic neurons (i.e., increased glutamatergic function; Chen et al., 2008). However, this enhanced synaptic strength persists and is resistant to extinction in rats that self-administer cocaine only and not in rats that self-administer a non-drug reinforcer (Chen et al., 2008). Interestingly, several lines of evidence suggest that the participation of the VTA in cocaine-induced neuronal and behavioral changes requires Orx/Hcrt inputs. For example, activation of Hcrt-r1 in the VTA is necessary for the development of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization (Borgland et al., 2006), and Orx-A/Hcrt-1-mediated N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor plasticity in the VTA is increased in rats that self-administer cocaine (Borgland et al., 2009). Additionally, short-lasting neuroadaptations in VTA dopaminergic neurons induced by high-fat chocolate food pellets have been described (Borgland et al., 2009), suggesting that the Orx/Hcrt-VTA system initially participates in the regulation of the motivation to obtain potent reinforcers in general (i.e., drug or highly palatable food). In contrast, drug-induced neuroadaptation of the Orx/Hcrt-VTA system is long-lasting, an effect that may be linked to the possible tilting of this system toward promoting and controlling drug-directed behavior.

Implication of Orx/Hcrt-PVT transmission in maladaptive (drug-seeking) behavior

Anatomically, it has been shown that the PVT is the target of numerous hypothalamic peptides involved in energy homeostasis (Freedman and Cassell, 1994; Otake, 2005), including Orx/Hcrt (Kirouac et al., 2005, 2006; Ishibashi et al., 2005). It is believed that the PVT plays a key role in energy homeostasis, arousal, temperature modulation, endocrine regulation, and reward (Bhatnagar and Dallman, 1998, 1999; Van Der Werf et al., 2002; Kelley et al., 2005; Parsons et al., 2006). Specifically and particularly important for this review, lesions of the PVT were shown to increase feeding behavior and body weight (Bhatnagar and Dallman, 1999) while attenuating the increases in both locomotor activity and blood corticosterone levels normally seen during the anticipation of food reward (Nakahara et al., 2004). Furthermore, the PVT was shown to be critically involved in mediating the effects of Orx/Hcrt on brain dopamine levels and reward-based feeding behaviors (Choi et al., 2012). These findings strongly suggest an important role for Orx/Hcrt-PVT signaling in food intake regulation.

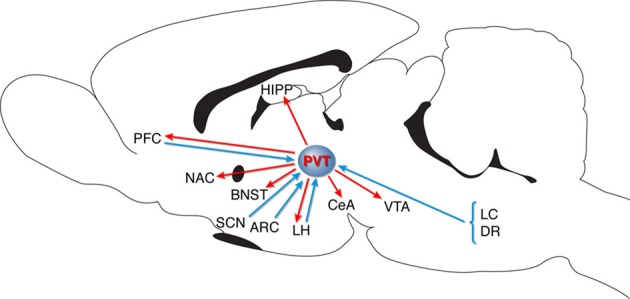

A major Orx/Hcrt projection exists from the LH/PFA to the PVT (Kirouac et al., 2005; Parsons et al., 2006), and the PVT has been proposed to be a key relay (see Figure 1), gating Orx/Hcrt-coded reward-related communication between the LH/PFA and both the ventral and dorsal striatum (Kelley et al., 2005). This “hypothalamic-thalamic-striatal axis” may have evolved to prolong central motivational states and promote feeding beyond the fulfillment of immediate energy needs, thereby creating energy reserves for potential future food shortages (Kelley et al., 2005). With regard to “drug seeking-related brain regions,” it is important to note that the PVT specifically projects to the CeA, BNST, NAC, VTA, and hippocampus (e.g., Kelley and Berridge, 2002; Kelley et al., 2005; Parsons et al., 2006; Hsu and Price, 2009; Martin-Fardon et al., 2010). Finally, recent data have shown that the PVT receives projections from the PFC, suggesting that these connections could modulate the expression of emotional behaviors (Li and Kirouac, 2012).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram representing PVT connectivity. PVT, paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus; LC, locus coeruleus; DR, dorsal raphe; VTA, ventral tegmental area; CeA, central nucleus of the amygdala; LH, lateral hypothalamus; ARC, arcuate nucleus; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; NAC, nucleus accumbens; PFC, prefrontal cortex; HIPP, hippocampus (for details, see Kelley and Berridge, 2002; Kelley et al., 2005; Kirouac et al., 2005; Parsons et al., 2006; Hsu and Price, 2009; Martin-Fardon et al., 2010; Li and Kirouac, 2012).

Although not usually thought of as part of drug-seeking neurocircuitry, direct and indirect findings recently supported a role for Orx/Hcrt-PVT signaling in drug-oriented behaviors. First, acute nicotine treatment was shown to activate Orx/Hcrt neurons that project to the basal forebrain and PVT, supporting a role for the Orx/Hcrt system in mediating certain aspects of nicotine-elicited wakefulness rather than proving a role for Orx/Hcrt-PVT signaling in tobacco addiction (Pasumarthi and Fadel, 2008), but such a link cannot be underestimated until proven false. Second, Orx/Hcrt peptides within the PVT have been suggested to regulate negative emotional states (Li et al., 2010a,b). Orx/Hcrt-PVT signaling was also shown to be critically involved in the expression of conditioned place aversion to morphine withdrawal (Li et al., 2011). These latter two observations may support a role for Orx-Hcrt signaling within the PVT in the negative emotional state that is putatively responsible for triggering the urge to seek drug during withdrawal of after a period of abstinence. A more direct observation confirmed that drug-related contextual cues activate Orx/Hcrt neurons (Dayas et al., 2008). Indeed, significantly larger numbers of Fos-positive hypothalamic Orx/Hcrt neurons were seen in rats exposed to contextual stimuli previously associated with ethanol availability compared with rats exposed to the same stimulus previously paired with non-reward. Moreover, presentation of the ethanol-related stimuli also increased the number of Fos-positive PVT neurons, and these neurons were closely associated with Orx/Hcrt fibers (for additional details, see Dayas et al., 2008). Other evidence supports a role for Orx/Hcrt projections from the LH to PVT in regulating drug-seeking behavior. Recent data confirmed that context-induced reinstatement of alcoholic beer seeking is associated with recruitment of a PVT-ventral striatum pathway and that excitotoxic lesion of this structure (Hamlin et al., 2009) or discrete administration of a κ opioid receptor agonist (Marchant et al., 2010) prevents context-induced reinstatement of alcohol seeking. In conclusion, it is hypothesized that maladaptive recruitment of the Orx/Hcrt system by drugs of abuse may tilt its function toward excessive drug-directed behavior, which may explain the increased sensitivity of this peptidergic system to antagonist interference with drug-seeking behavior as opposed to behavior directed toward natural rewards.

Furthermore, it was recently shown that although Orx/Hcrt microinjections into the PVT exerted a priming-like effect, reinstating both extinguished cocaine- and SCM-seeking behavior, Orx/Hcrt produced (1) two different dose-response functions for cocaine seeking vs. SCM seeking and (2) a stronger reinstatement of cocaine seeking vs. SCM seeking at moderate doses (Martin-Fardon et al., 2011). This observation suggests of a leftward shift of the Orx-A/Hcrt-1 dose-response curve in cocaine-experienced animals, implying that cocaine produced a dysregulation of Orx/Hcrt-PVT transmission that is revealed following exogenous Orx/Hcrt administration. Moreover, recent findings have demonstrated that discrete inactivation of the PVT with tetrodotoxin (TTX) prevented cocaine priming-induced reinstatement (James et al., 2010), further implicating this thalamic structure in drug-seeking behavior, although the same researchers claimed that Orx/Hcrt-1 receptor signaling within the VTA but not PVT was critical in the regulation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behaviors (James et al., 2011).

Conclusion/perspectives

Currently, the available therapeutic approaches fail to completely treat and address the compulsive nature of drug seeking and drug taking associated with addiction. Evidence indicates that dysfunctional Orx/Hcrt transmission contributes to drug seeking vs. natural reward seeking, and an increasing amount of data has now identified the PVT, a brain region not usually included in the neurocircuitry of addiction, to be recruited by drugs of abuse, opening up a new area of targets for efficient pharmacotherapy.

Notably, however, drug addiction is often associated with increased drug consumption that can modify the pharmacological profile of promising therapeutic agents, possibly resulting in drug-induced neuroadaptation (for review, see Kalivas and O'Brien, 2008; Moussawi et al., 2009). For instance, following extended-access cocaine self-administration (6 h/day), it was shown that (-)-2-oxa-4-aminobicylco[3.1.0]hexane-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (LY379268), a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) 2/3 agonist, became more efficient at preventing anxiety-like behavior and decreasing cocaine self-administration (Aujla et al., 2008; Hao et al., 2010), whereas the effects of an mGluR5 antagonist, 3-[(2-methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]piperidine (MTEP), were blunted (Hao et al., 2010). A similar behavioral pharmacological profile was observed in animals that had a history of alcohol dependence, in which LY379268 and MTEP dose-dependently reduced both alcohol self-administration and the reinstatement of alcohol seeking induced by footshock stress, but LY379268 was more effective than MTEP in inhibiting both behaviors in postdependent animals compared with non-dependent animals (Sidhpura et al., 2010). Consequently, considering the importance of relapse prevention in postdependent individuals, important issues that require further research are to identify (1) whether Orx/Hcrt-PVT transmission becomes further dysfunctional following dependence and (2) the most effective pharmacological tools (i.e., Hcrt-r antagonists) for relapse and craving prevention in postdependent individuals.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This is publication number 21836 from The Scripps Research Institute. This research was supported by NIH/NIDA grant DA033344 (Rémi Martin-Fardon) and Swiss National Science Foundation grants 3100A0-112101 and 3100A0-133056 (Benjamin Boutrel). The authors thank G. Cauvi and M. Arends for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Ammoun S., Holmqvist T., Shariatmadari R., Oonk H. B., Detheux M., Parmentier M., et al. (2003). Distinct recognition of OX1 and OX2 receptors by orexin peptides. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 305, 507–514 10.1124/jpet.102.048025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G., Harris G. C. (2004). Brain substrates for increased drug seeking during protracted withdrawal. Neuropharmacology 47(Suppl. 1), 167–179 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aujla H., Martin-Fardon R., Weiss F. (2008). Rats with extended access to cocaine exhibit increased stress reactivity and sensitivity to the anxiolytic-like effects of the mGluR 2/3 agonist LY379268 during abstinence. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 1818–1826 10.1038/sj.npp.1301588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo B. A., Daniel R. A., Berridge C. W., Kelley A. E. (2003). Overlapping distributions of orexin/hypocretin- and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase immunoreactive fibers in rat brain regions mediating arousal, motivation, and stress. J. Comp. Neurol. 464, 220–237 10.1002/cne.10783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D., Everitt B. J. (2008). Cocaine seeking habits depend upon dopamine-dependent serial connectivity linking the ventral with the dorsal striatum. Neuron 57, 432–441 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S., Dallman M. (1998). Neuroanatomical basis for facilitation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal responses to a novel stressor after chronic stress. Neuroscience 84, 1025–1039 10.1016/S0306-4522(97)00577-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar S., Dallman M. F. (1999). The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus alters rhythms in core temperature and energy balance in a state-dependent manner. Brain Res. 851, 66–75 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)02108-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonci A., Borgland S. (2009). Role of orexin/hypocretin and CRF in the formation of drug-dependent synaptic plasticity in the mesolimbic system. Neuropharmacology 56(Suppl. 1), 107–111 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland S. L., Chang S. J., Bowers M. S., Thompson J. L., Vittoz N., Floresco S. B., et al. (2009). Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. J. Neurosci. 29, 11215–11225 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6096-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland S. L., Taha S. A., Sarti F., Fields H. L., Bonci A. (2006). Orexin A in the VTA is critical for the induction of synaptic plasticity and behavioral sensitization to cocaine. Neuron 49, 589–601 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B., Cannella N., De Lecea L. (2010). The role of hypocretin in driving arousal and goal-oriented behaviors. Brain Res. 1314, 103–111 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B., Kenny P. J., Specio S. E., Martin-Fardon R., Markou A., Koob G. F., et al. (2005). Role for hypocretin in mediating stress-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19168–19173 10.1073/pnas.0507480102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calipari E. S., Espana R. A. (2012). Hypocretin/orexin regulation of dopamine signaling: implications for reward and reinforcement mechanisms. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 6:54 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal R. N., Parkinson J. A., Hall J., Everitt B. J. (2002). Emotion and motivation: the role of the amygdala, ventral striatum, and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 26, 321–352 10.1016/S0149-7634(02)00007-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. T., Bowers M. S., Martin M., Hopf F. W., Guillory A. M., Carelli R. M., et al. (2008). Cocaine but not natural reward self-administration nor passive cocaine infusion produces persistent LTP in the VTA. Neuron 59, 288–297 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. L., Davis J. F., Magrisso I. J., Fitzgerald M. E., Lipton J. W., Benoit S. C. (2012). Orexin signaling in the paraventricular thalamic nucleus modulates mesolimbic dopamine and hedonic feeding in the rat. Neuroscience 210, 243–248 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daglish M. R., Nutt D. J. (2003). Brain imaging studies in human addicts. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 13, 453–458 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayas C. V., McGranahan T. M., Martin-Fardon R., Weiss F. (2008). Stimuli linked to ethanol availability activate hypothalamic CART and orexin neurons in a reinstatement model of relapse. Biol. Psychiatry 63, 152–157 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLeone R. J., Georgescu D., Nestler E. J. (2003). Lateral hypothalamic neuropeptides in reward and drug addiction. Life Sci. 73, 759–768 10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00408-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C. M., Abusnana S., Sunter D., Murphy K. G., Ghatei M. A., Bloom S. R. (1999). The effect of the orexins on food intake: comparison with neuropeptide Y, melanin-concentrating hormone and galanin. J. Endocrinol. 160, R7–R12 10.1677/joe.0.160R007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana R. A., Oleson E. B., Locke J. L., Brookshire B. R., Roberts D. C., Jones S. R. (2010). The hypocretin-orexin system regulates cocaine self-administration via actions on the mesolimbic dopamine system. Eur. J. Neurosci. 31, 336–348 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07065.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt B. J., Dickinson A., Robbins T. W. (2001). The neuropsychological basis of addictive behaviour. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 36, 129–138 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00088-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman L. J., Cassell M. D. (1994). Relationship of thalamic basal forebrain projection neurons to the peptidergic innervation of the midline thalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 348, 321–342 10.1002/cne.903480302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein R. Z., Volkow N. D. (2002). Drug addiction and its underlying neurobiological basis: neuroimaging evidence for the involvement of the frontal cortex. Am. J. Psychiatry 159, 1642–1652 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J. A., Jensen L. T., Fugger L., Burdakov D. (2012). Convergent inputs from electrically and topographically distinct orexin cells to locus coeruleus and ventral tegmental area. Eur. J. Neurosci. 35, 1426–1432 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08057.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin A. S., Clemens K. J., Choi E. A., McNally G. P. (2009). Paraventricular thalamus mediates context-induced reinstatement (renewal) of extinguished reward seeking. Eur. J. Neurosci. 29, 802–812 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06623.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao Y., Martin-Fardon R., Weiss F. (2010). Behavioral and functional evidence of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 dysregulation in cocaine-escalated rats: factor in the transition to dependence. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 240–248 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. C., Aston-Jones G. (2006). Arousal and reward: a dichotomy in orexin function. Trends Neurosci. 29, 571–577 10.1016/j.tins.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris G. C., Wimmer M., Aston-Jones G. (2005). A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature 437, 556–559 10.1038/nature04071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A. C., Chapman H., Taylor C., Moore G. B., Cawthorne M. A., Tadayyon M., et al. (2002). Anorectic, thermogenic and anti-obesity activity of a selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist in ob/ob mice. Regul. Pept. 104, 153–159 10.1016/S0167-0115(01)00358-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes A. C., Jackson B., Chapman H., Tadayyon M., Johns A., Porter R. A., et al. (2000). A selective orexin-1 receptor antagonist reduces food consumption in male and female rats. Regul. Pept. 96, 45–51 10.1016/S0167-0115(00)00199-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander J. A., Lu Q., Cameron M. D., Kamenecka T. M., Kenny P. J. (2008). Insular hypocretin transmission regulates nicotine reward. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 19480–19485 10.1073/pnas.0808023105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu D. T., Price J. L. (2009). Paraventricular thalamic nucleus: subcortical connections and innervation by serotonin, orexin, and corticotropin-releasing hormone in macaque monkeys. J. Comp. Neurol. 512, 825–848 10.1002/cne.21934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi M., Takano S., Yanagida H., Takatsuna M., Nakajima K., Oomura Y., et al. (2005). Effects of orexins/hypocretins on neuronal activity in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus in rats in vitro. Peptides 26, 471–481 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R., Dalley J. W., Robbins T. W., Everitt B. J. (2002). Dopamine release in the dorsal striatum during cocaine-seeking behavior under the control of a drug-associated cue. J. Neurosci. 22, 6247–6253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. H., Charnley J. L., Jones E., Levi E. M., Yeoh J. W., Flynn J. R., et al. (2010). Cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) signaling within the paraventricular thalamus modulates cocaine-seeking behaviour. PLoS ONE 5:e12980 10.1371/journal.pone.0012980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. H., Charnley J. L., Levi E. M., Jones E., Yeoh J. W., Smith D. W., et al. (2011). Orexin-1 receptor signalling within the ventral tegmental area, but not the paraventricular thalamus, is critical to regulating cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 14, 684–690 10.1017/S1461145711000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B., Krivdic B., Krstew E., Lawrence A. J. (2011). The orexin receptor antagonist SB-334867 dissociates the motivational properties of alcohol and sucrose in rats. Brain Res. 1391, 54–59 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jupp B., Krstew E., Dezsi G., Lawrence A. J. (2011). Discrete cue-conditioned alcohol-seeking after protracted abstinence: pattern of neural activation and involvement of orexin receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 162, 880–889 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01088.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas P. W., O'Brien C. (2008). Drug addiction as a pathology of staged neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 166–180 10.1038/sj.npp.1301564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas P. W., Volkow N. D. (2005). The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1403–1413 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley A. E., Baldo B. A., Pratt W. E. (2005). A proposed hypothalamic-thalamic-striatal axis for the integration of energy balance, arousal, and food reward. J. Comp. Neurol. 493, 72–85 10.1002/cne.20769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley A. E., Berridge K. C. (2002). The neuroscience of natural rewards: relevance to addictive drugs. J. Neurosci. 22, 3306–3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirouac G. J., Parsons M. P., Li S. (2005). Orexin (hypocretin) innervation of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Brain Res. 1059, 179–188 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirouac G. J., Parsons M. P., Li S. (2006). Innervation of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus from cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART) containing neurons of the hypothalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 497, 155–165 10.1002/cne.20971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence A. J., Cowen M. S., Yang H. J., Chen F., Oldfield B. (2006). The orexin system regulates alcohol-seeking in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 148, 752–759 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leshner A. I. (1997). Addiction is a brain disease, and it matters. Science 278, 45–47 10.1126/science.278.5335.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Kirouac G. J. (2012). Sources of inputs to the anterior and posterior aspects of the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Brain Struct. Funct. 217, 257–273 10.1007/s00429-011-0360-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li S., Wei C., Wang H., Sui N., Kirouac G. J. (2010a). Changes in emotional behavior produced by orexin microinjections in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 95, 121–128 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li S., Wei C., Wang H., Sui N., Kirouac G. J. (2010b). Orexins in the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus mediate anxiety-like responses in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 212, 251–265 10.1007/s00213-010-1948-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang H., Qi K., Chen X., Li S., Sui N., et al. (2011). Orexins in the midline thalamus are involved in the expression of conditioned place aversion to morphine withdrawal. Physiol. Behav. 102, 42–50 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant N. J., Furlong T. M., McNally G. P. (2010). Medial dorsal hypothalamus mediates the inhibition of reward seeking after extinction. J. Neurosci. 30, 14102–14115 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4079-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R., Leos B. N., Kerr T. M., Weiss F. (2011). Administration of Orexin/Hypocretin (Orx/Hcrt) in the Paraventricular Nucleus of the Thalamus (PVT) Produces Cocaine-Seeking: Comparison with Natural Reward-Seeking. Program No. 69.10. 2011 Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Washington, DC: Society for Neuroscience; [Online]. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R., Weiss F. (2009). Differential Effects of an Orx/Hcrt Antagonist on Reinstatement Induced by a Cue Conditioned to Cocaine vs. Palatable Natural Reward. Program No. 65.21. 2009 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, Chicago, IL: Society for Neuroscience; [Online]. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R., Weiss F. (2012). N-(2-methyl-6-ben zoxazolyl)-N'-1, 5-naphthyridin-4-yl urea (SB334867), a hypocretin receptor-1 antagonist, preferentially prevents ethanol seeking: comparison with natural reward seeking. Addict. Biol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00480.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R., Zorrilla E. P., Ciccocioppo R., Weiss F. (2010). Role of innate and drug-induced dysregulation of brain stress and arousal systems in addiction: focus on corticotropin-releasing factor, nociceptin/orphanin FQ, and orexin/hypocretin. Brain Res. 1314, 145–161 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K., Kalivas P. W. (2001). The circuitry mediating cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J. Neurosci. 21, 8655–8663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A. T., Lewis D. C., O'Brien C. P., Kleber H. D. (2000). Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA 284, 1689–1695 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller N. S., Goldsmith R. J. (2001). Craving for alcohol and drugs in animals and humans: biology and behavior. J. Addict. Dis. 20, 87–104 10.1300/J069v20n03_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussawi K., Pacchioni A., Moran M., Olive M. F., Gass J. T., Lavin A., et al. (2009). N-Acetylcysteine reverses cocaine-induced metaplasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 182–189 10.1038/nn.2250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara K., Fukui K., Murakami N. (2004). Involvement of thalamic paraventricular nucleus in the anticipatory reaction under food restriction in the rat. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 66, 1297–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien C. P., Childress A. R., Ehrman R., Robbins S. J. (1998). Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? J. Psychopharmacol. 12, 15–22 10.1177/026988119801200103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien C. P., McLellan A. T. (1996). Myths about the treatment of addiction. Lancet 347, 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otake K. (2005). Cholecystokinin and substance P immunoreactive projections to the paraventricular thalamic nucleus in the rat. Neurosci. Res. 51, 383–394 10.1016/j.neures.2004.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons M. P., Li S., Kirouac G. J. (2006). The paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus as an interface between the orexin and CART peptides and the shell of the nucleus accumbens. Synapse 59, 480–490 10.1002/syn.20264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasumarthi R. K., Fadel J. (2008). Activation of orexin/hypocretin projections to basal forebrain and paraventricular thalamus by acute nicotine. Brain Res. Bull. 77, 367–373 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C., Tighe D. K., Van Den Pol A. N., De Lecea L., Heller H. C., Sutcliffe J. G., et al. (1998). Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J. Neurosci. 18, 9996–10015 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards J. K., Simms J. A., Steensland P., Taha S. A., Borgland S. L., Bonci A., et al. (2008). Inhibition of orexin-1/hypocretin-1 receptors inhibits yohimbine-induced reinstatement of ethanol and sucrose seeking in Long-Evans rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 199, 109–117 10.1007/s00213-008-1136-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T., Amemiya A., Ishii M., Matsuzaki I., Chemelli R. M., Tanaka H., et al. (1998). Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92, 573–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor G. C., Aston-Jones G. S. (2012). A septal-hypothalamic pathway drives orexin neurons, which is necessary for conditioned cocaine preference. J. Neurosci. 32, 4623–4631 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4561-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammell T. E., Winrow C. J. (2011). Orexin receptors: pharmacology and therapeutic opportunities. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 51, 243–266 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See R. E. (2002). Neural substrates of conditioned-cued relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 71, 517–529 10.1016/S0091-3057(01)00682-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidhpura N., Weiss F., Martin-Fardon R. (2010). Effects of the mGlu2/3 agonist LY379268 and the mGlu5 antagonist MTEP on ethanol seeking and reinforcement are differentially altered in rats with a history of ethanol dependence. Biol. Psychiatry 67, 804–811 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. J., Tahsili-Fahadan P., Aston-Jones G. (2010). Orexin/hypocretin is necessary for context-driven cocaine-seeking. Neuropharmacology 58, 179–184 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steketee J. D., Kalivas P. W. (2011). Drug wanting: behavioral sensitization and relapse to drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 348–365 10.1124/pr.109.001933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe J. G., de Lecea L. (2002). The hypocretins: setting the arousal threshold. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 339–349 10.1038/nrn808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri S., Zeitzer J. M., Mignot E. (2002). The role of hypocretins (orexins) in sleep regulation and narcolepsy. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 25, 283–313 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teske J. A., Billington C. J., Kotz C. M. (2010). Hypocretin/orexin and energy expenditure. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 198, 303–312 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. L., Borgland S. L. (2011). A role for hypocretin/orexin in motivation. Behav Brain Res. 217, 446–453 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.09.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Werf Y. D., Witter M. P., Groenewegen H. J. (2002). The intralaminar and midline nuclei of the thalamus. Anatomical and functional evidence for participation in processes of arousal and awareness. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 39, 107–140 10.1016/S0165-0173(02)00181-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanat M. J., Willuhn I., Clark J. J., Phillips P. E. (2009). Phasic dopamine release in appetitive behaviors and drug addiction. Curr. Drug Abuse Rev. 2, 195–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. (2005). Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 5, 9–19 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willie J. T., Chemelli R. M., Sinton C. M., Yanagisawa M. (2001). To eat or to sleep? Orexin in the regulation of feeding and wakefulness. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 429–458 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winsky-Sommerer R., Yamanaka A., Diano S., Borok E., Roberts A. J., Sakurai T., et al. (2004). Interaction between the corticotropin-releasing factor system and hypocretins (orexins): a novel circuit mediating stress response. J. Neurosci. 24, 11439–11448 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3459-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]