Abstract

Objective: The corollary discharge mechanism is theorized to dampen sensations resulting from our own actions and distinguish them from environmental events. Deficits in this mechanism in schizophrenia may contribute to misperceptions of self-generated sensations as originating from external stimuli. We previously found attenuated speech-related suppression of auditory cortex in chronic patients, consistent with such deficits. Whether this abnormality precedes psychosis onset, emerges early in the illness, and/or progressively worsens with illness chronicity, is unknown. Methods: Event-related potentials (ERPs) were recorded from schizophrenia patients (SZ; n = 75) and age-matched healthy controls (HC; n = 77). A subsample of early illness schizophrenia patients (ESZ; n = 39) was compared with patients at clinical high-risk for psychosis (CHR; n = 35) and to a subgroup of age-matched HC (n = 36) during a Talk-Listen paradigm. The N1 ERP component was elicited by vocalizations as subjects talked (Talk) and heard them played back (Listen). Results: As shown previously, SZ showed attenuated speech-related N1 suppression relative to HC. This was also observed in ESZ. N1 suppression values in CHR were intermediate to HC and ESZ and not statistically distinguishable from either comparison group. Age-corrected N1 Talk-Listen difference z scores were not correlated with illness duration in the full SZ sample. Conclusions: Putative dysfunction of the corollary discharge mechanism during speech is evident early in the illness and is stable over its course. The intermediate effects in CHR patients may reflect the heterogeneity of this group, requiring longitudinal follow-up data to address if speech-related N1 suppression abnormalities are a risk marker for conversion to psychosis.

Keywords: psychosis, clinical high-risk, self-monitoring, forward model, corollary discharge

Sensations resulting from our own actions are experienced differently than sensations produced by others. When we move our eyes, we do not perceive a moving room; even ticklish people cannot tickle themselves.1 It is posited that this is due to the “efference copy/corollary discharge” system, which both dampens the sensations resulting from our own actions and tags them as coming from “self”.2 Its neurobiology has been described across the animal kingdom3: it allows the cricket to sing without deafening itself; it allows bats to distinguish their own sonar signals from those produced by others.4 Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably and were coined in the 1950s5 , 6 to describe similar phenomena, recent theorists of motor-sensory feed-forward systems have found it useful to distinguish between the efference copy, defined as a copy of an impending motor plan sent from motor to sensory cortical areas, and the corollary discharge, defined as the expected sensory consequences of the motor act, generated in the sensory cortex by the arrival of the efference copy. When there is a match between the corollary discharge and the stimulation produced by execution of the motor plan (the sensory reafference), sensation is dampened or canceled and tagged as self-generated.2 Here, we will use the term “corollary discharge”.

Operation of the corollary discharge mechanism in the auditory system was empirically supported by recordings from the temporal cortex in neurosurgical patients while they talked and listened to others talking.7 During listening, all recorded neurons in superior temporal gyrus responded to speech within 200 ms of its onset. During overt talking, suppression of ongoing activity in ∼1/3 of middle temporal gyrus neurons preceded vocalization by a few hundred milliseconds and outlasted it up to 1s. However, while evidence of the corollary discharge mechanism is present in the auditory cortex, it is possible these effects could originate at a lower level in the auditory pathway.3

Auditory cortical suppression during speech is further supported by recordings from single units in primary auditory cortex in monkeys during vocalization.8 To study this phenomenon in humans, several groups have used electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography to record auditory cortical response to speech as it is being spoken.9 – 12 Auditory cortical excitation is reflected in the N1 component of the event-related potential (ERP),13 a negative-going potential generated in primary and secondary auditory cortices,14 occurring ∼100 ms poststimulus. N1 amplitude to speech sounds is suppressed during speaking compared with listening to a recording of the sounds.9 – 11 We and others suggest that this suppression results from a match between the corollary discharge and the sensory reafference10 , 11 and the closer the match the greater the suppression.15

Corollary Discharge Dysfunction in Schizophrenia

In addition to dampening irrelevant sensations resulting from our own actions, the feed-forward model provides a mechanism for automatic distinction between internally and externally generated percepts across sensory modalities and may even operate in the realm of covert thoughts, which have been viewed as our most complex motor act.16 Feinberg17 initially suggested that dysfunctional corollary discharge mechanisms may underlie symptoms that characterize schizophrenia. Frith18 expanded this concept, motivating a series of behavioral experiments confirming corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia.19 Evidence for dysfunction of the corollary discharge system in schizophrenia has been documented in auditory,9 , 20 – 24 visual,25 and somatosensory modalities.19 , 26

Measuring the auditory N1 during a Talk-Listen paradigm, we found that normal dampening of auditory N1 amplitude during talking, relative to listening, is attenuated in chronic schizophrenia patients.9 , 23 , 24 However, it is unknown whether the speech-related N1 suppression abnormalities observed in schizophrenia patients are present in early stages of the illness, predate the onset of psychosis, and/or progress across the course of the illness. These questions can be addressed by studying patients early in their illness, patients clinically at high-risk for developing psychosis, and patients spanning a large range of illness durations. Early illness is typically defined as the first couple years of illness, (eg, ref. 27). Clinical high-risk (CHR) is based on the Criteria of Prodromal Syndromes (COPS28) and the similar criteria for At Risk Mental States.29 The North American Prodromal Longitudinal Study consortium reported that 35% of patients meeting COPS criteria converted to a psychotic disorder within a 2.5-year follow-up period.30

An increasing number of studies have found many of the electrophysiological abnormalities associated with schizophrenia to be evident in CHR patients31 – 33; however, none has assessed whether electrophysiological evidence of corollary discharge dysfunction is present in these patients. Corollary discharge dysfunction in CHR patients may reflect vulnerability to the disorder and/or abnormal neurodevelopment. Moreover, effects of antipsychotic medications on the corollary discharge mechanism have not been examined. Studying an antipsychotic-free sample of clinically high-risk patients provides an opportunity to assess the role of antipsychotics in producing this abnormality, a confound present in all prior studies of corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia.

In spite of the possible contribution of corollary discharge dysfunction to positive symptoms in schizophrenia, finding a relationship between positive symptoms and the corollary discharge system has been more successful using prespeech neural synchrony than N1 suppression.9,23,24 Importantly, these studies all involved chronic patients, in whom the relationship between neurobiology and clinical presentation may have been obscured by prolonged treatment and the sequelae of the disease.

Goals of This Study

In order to assess whether putative corollary discharge modulation of auditory cortex responsiveness during speech is compromised early in the course of schizophrenia, we recorded ERPs to vocalizations as they were being produced and during their playback using our previously described Talk-Listen paradigm12 in 3 groups: schizophrenia patients, clinically high-risk patients, and healthy controls (HCs). A subset of patients within their first 2.5 years of the disorder was defined as being early in their illness. Based on our hypothesis that corollary discharge dysfunction is a core pathophysiological process in schizophrenia, we predicted that early illness patients would show diminished speech-related N1 suppression, similar to our prior observations in chronic patients.9 , 20 – 24 Based on the hypothesis that corollary discharge dysfunction is a risk marker for the development of psychosis, we also predicted that clinically high-risk patients would exhibit speech-related N1 suppression abnormalities. However, given the heterogeneous nature of patients in at-risk samples, with only a minority destined to convert to schizophrenia, we predicted that their abnormality would be intermediate relative to early illness patients and HCs. Furthermore, to examine whether corollary discharge dysfunction progressively worsens with illness severity, we asked whether the degree of abnormality present in N1 suppression, relative to values expected based on normal aging, is correlated with illness duration across the full schizophrenia sample. Accordingly, we studied patients spanning 3 months to 42 years of illness duration.

Methods

Participants

Study participants included 40 patients at CHR for psychosis based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes,28 81 patients with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, (DSM-IV) schizophrenia (SZ) based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID), and 89 HC subjects. CHR patients met criteria for at least 1 of the 3 subsyndromes defined by the COPS28: (1) Attenuated Positive Symptoms, (2) Brief Intermittent Psychotic States, and (3) Genetic Risk with Deterioration in social/occupational functioning. Among the SZ, a subsample of 41 patients were identified as early illness (ESZ), defined as being within 2.5 years of initial hospitalization for psychosis or initiation of antipsychotic medication. Interviews were conducted by a trained research assistant, psychiatrist, or clinical psychologist.

Out of the 89 HC subjects, an age-matched group of 86 HCs (age range 16-59) was used for comparison for the full SZ group. In addition, an overlapping subgroup of 42 HCs (age range 13-32) was age matched to CHR and ESZ patients for group comparisons.

HC were recruited by advertisements and word-of-mouth. Exclusion criteria for HC included a past or current DSM-IV Axis I disorder based on a SCID interview or having a first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder. Exclusion criteria for all groups included a history of substance dependence or abuse within the past year, a history of a significant medical or neurological illness, or a history of head injury resulting in loss of consciousness. The study was approved by the institutional review board of University of California, San Francisco, and adult participants provided written informed consent. In the case of minors, parents provided written informed consent; youths provided written informed assent (table 1).

Table 1.

Group Demographic Dataa

| Schizophrenia (SZ) Patients n = 75 | Healthy Controls (HC) Age-Matched to SZ Patients n = 75 | X 2 | P Value | Clinical High-Risk (CHR) Patients n = 35 | Early Illness Schizophrenia (ESZ) Patients n = 39 | HC Age-Matched to ESZ and CHR Patients n = 36 | X 2 | P value | |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||||||

| Gender | 19.6 | <.001 | 4.7 | .094 | |||||||||||

| Female (F) | 20 | 26.7 | 48 | 62.3 | 16 | 45.7 | 9 | 23.1 | 15 | 41.7 | |||||

| Male (M) | 55 | 73.3 | 29 | 37.7 | 19 | 54.3 | 30 | 76.9 | 21 | 58.3 | |||||

| Handednessb | 4.0 | .399 | 4.8 | .314 | |||||||||||

| Right | 65 | 86.7 | 71 | 92.2 | 28 | 80.0 | 36 | 92.3 | 32 | 88.9 | |||||

| Left | 6 | 8.0 | 5 | 6.5 | 4 | 11.4 | 2 | 5.1 | 3 | 8.3 | |||||

| Both | 4 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.3 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.8 | |||||

| Diagnostic subtype | |||||||||||||||

| Paranoid | 35 | 46.7 | 15 | 38.5 | |||||||||||

| Disorganized | 7 | 9.3 | 5 | 12.8 | |||||||||||

| Undifferentiated | 7 | 9.3 | 2 | 5.1 | |||||||||||

| Residual | 4 | 5.3 | 2 | 5.1 | |||||||||||

| Schizoaffective | 20 | 26.7 | 13 | 33.4 | |||||||||||

| Schizophreniform | 2 | 2.7 | 2 | 5.1 | |||||||||||

| CHR criteriac | |||||||||||||||

| APS | 34 | 97.1 | |||||||||||||

| BIPS | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||||||||

| GRD | 9 | 25.7 | |||||||||||||

| Antipsychotic type | |||||||||||||||

| Atypical | 58 | 77.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 31 | 79.5 | |||||||||

| Typical | 8 | 10.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 10.3 | |||||||||

| Both | 6 | 8.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 7.7 | |||||||||

| None | 3 | 4.0 | 35 | 100.0 | 1 | 2.6 | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | F | P value | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | P value | Post hoc contrasts | |

| Age, years | 28.03 | 11.6 | 30.45 | 10.6 | 1.8 | 0.181 | 19.48 | 3.7 | 21.45 | 4.05 | 21.16 | 3.2 | 2.88 | 0.060 | ESZ = CHR = HC |

| Parental SESd | 34.32 | 14.4 | 35.72 | 15.1 | 0.33 | 0.565 | 35.3 | 16.6 | 31.45 | 13.58 | 34.65 | 16.1 | 0.67 | 0.515 | ESZ = CHR = HC |

| PANSS total | 65.69 | 16.30 | 65.54 | 16.91 | |||||||||||

| SOPS total | 34.54 | 13.40 | |||||||||||||

Note: PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SOPS, Scale of Prodromal Symptoms; APS, Attenuated Positive Symptoms; BIPS, Brief Intermittent Psychotic Symptoms; GRD, Genetic Risk and Deterioration; SES, socioeconomic status

Values are given as number and percentage of subjects for gender, handedness, diagnostic subtype, CHR criteria, and antipsychotic type. Group means with the SD for age, parental SES, PANSS, and SOPS are reported. Gender and handedness were analyzed with Pearson chi-square tests. Age and parental SES were analyzed with one-way ANOVA and Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests.

The Crovitz-Zener (1962) questionnaire was used to measure handedness.

CHR criteria APS, BIPS, and GRD are not mutually exclusive.

The Hollingshead (1975) 4-factor index of parental SES is based on a composite of maternal education, paternal education, maternal occupational status, and paternal occupational status. Lower scores represent higher SES. SES values are missing from 2 SZ patients (n = 2) and 1 HC subject (n = 1).

Clinical Ratings

Within 4 weeks of ERP assessment (M = 11.6, SD = 15.99 days), a clinically trained research assistant, psychiatrist, or clinical psychologist rated schizophrenia symptoms using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).34 Prodromal symptoms were rated using the Scale of Prodromal Symptoms (SOPS).28

Procedure

Participants completed the Talk-Listen paradigm, as described previously,12 using Presentation software (www.neurobs.com/presentation). In the Talk condition, participants were trained to pronounce short (<300 ms), sharp vocalizations of the phoneme “ah” repeatedly in a self-paced manner, about every 1–2s, for 180s. The speech was recorded using a microphone connected to the stimulus presentation computer and transmitted back to subjects through Etymotic ER3-A insert earphones in real time (zero delay). In the Listen condition, the recording from the Talk condition was played back, and participants were instructed simply to listen. The number of trials generated for both Talk and Listen conditions by SZ, CHR, and HC was not significantly different.

Acoustic Calibration and Standard Stimulus Generation

Participants were coached to produce “ah” vocalizations >75 dB and < 85 dB by monitoring intensity with a dB meter held ∼6 cm in front of the participant’s mouth. Sound intensity was kept the same in Talk and Listen conditions for each participant by ensuring that a 1000 Hz tone (generated by a Quest QC calibrator) produced equivalent dB intensities when delivered through earphones during the tone’s generation (Talk condition) and during its playback (Listen condition). In addition to recording “ah” vocalizations for playback, they were digitized and processed offline using an automated algorithm to identify vocalization onset.12 Trigger codes were inserted into the continuous EEG file at these onsets to allow time-locked epoching and averaging of the EEG. To examine group differences in hearing ability, a repeated measures Group × ear (left vs right) × Hz level (250, 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000) ANOVA was performed. No Group effects or any interactions involving Group were observed.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

EEG data were recorded from 64 channels using a BioSemi ActiveTwo system (www.biosemi.com). Electrodes placed at the outer canthi of both eyes, and above and below the right eye, were used to record vertical and horizontal electrooculogram (EOG) data. EEG data were continuously digitized at 1024 Hz and referenced offline to averaged earlobe electrodes before applying a 1 Hz high-pass filter using EEGLAB (http://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab/). Data were next subjected to Fully Automated Statistical Thresholding for EEG artifact Rejection (FASTER) using a freely distributed toolbox.35 The method employs multiple descriptive measures to search for statistical outliers (>±3 SD from mean). This process included 5 steps: (1) outlier channels were identified and replaced with interpolated values in continuous data, (2) outlier epochs were removed from participants’ single trial set, (3) spatial independent components analysis was applied to remaining trials, outlier components were identified (including components that correlated with EOG activity), and data were back-projected without these components, (4) within an epoch, outlier channels were removed and interpolated, and (5) ERP averages for the Talk and Listen conditions were separately assessed in each subject group to identify outlier subjects. Nine HC, 5 CHR, and 6 SZ (2 of whom were also characterized as ESZ) were excluded from further analysis based on this last step. The final samples consisted of (1) 75 SZ age-matched with 77 HC and (2) 39 ESZ, 35 CHR, and 36 age-matched HC. Epochs were time locked to the onset of each “ah” and baseline corrected 100 ms preceding vocalization. ERP averages were generated using a trimmed means approach, excluding the top and bottom 25% of single trial values at every data sample in the epoch before averaging to produce a more robust mean estimation.36

To address any remaining baseline contamination, a temporal Varimax-rotated principal components analysis was performed on the ERP data.37 ERPs were reconstructed by excluding factors with a maximum value preceding “ah” onset or that accounted for less than 0.5% of the variance (43.7% remained). N1 was identified in the ERP as the most negative peak between 60 and 140 ms after “ah” onset. N1 amplitude was quantified separately for Talk and Listen conditions by integrating the voltage in a 50 ms window centered on the peak. The N1 Talk-Listen suppression effect was estimated using the N1 Talk-Listen difference score at Cz.

Statistical Correction for Normal Aging Effects

To control for the effects of normal aging, we compared each patient group with an age-matched HC group. However, in order to examine the degree to which N1 suppression abnormalities are affected by illness duration, we derived a single age-corrected N1 suppression value for each subject. First, N1 Talk-Listen difference scores were regressed on age in the HC group (age range 13-59). Next, the resulting regression equation was used to calculate age-corrected N1 Talk-Listen difference z scores for all groups. The resulting age-corrected z scores reflected deviations from the HCs at a specific age. This method has been used previously38 and is preferable to using age as a covariate in an ANCOVA, which removes pathological aging effects from the patient data.

Statistical Analysis

For the comparison of the full SZ sample to their age-matched controls, Group differences in N1 Talk-Listen difference scores were assessed using an independent samples t test. In our secondary analysis, a one-way ANOVA was conducted to compare N1 Talk-Listen difference scores between ESZ, CHR, and their age-matched HC group. A significant Group effect was further parsed using post hoc Tukey-Kramer tests. To assess group differences in auditory processing of speech sounds, an independent samples t test compared the full SZ sample with their age-matched controls on N1 amplitude during the Listen condition. In addition, an ANOVA was conducted to compare N1 z scores between ESZ, CHR, and their age-matched HC group. Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests were used to examine pairwise comparisons.

In order to determine whether speech-related N1 suppression progressively worsened over the illness course independent of normal aging effects, duration of illness was correlated with age-corrected N1 Talk-Listen difference z scores within the full SZ sample.

To assess the relationship between symptom severity and speech-related N1 suppression abnormalities in the full SZ group, N1 Talk-Listen difference scores were correlated with positive (total sum of PANSS positive symptom ratings) and negative symptom (total sum of PANSS negative symptom ratings) summary scores. Correlations with SOPS positive and negative symptom summary scores were performed in the CHR group. A Bonferroni correction was applied for the number of correlations performed within each patient group.

Results

Demographic Differences Between Groups

Pearson chi-square analysis showed that gender significantly differed between the full SZ sample and their age-matched HC. Thus, the effect of gender was examined as a between-subjects factor in a Group analysis. There was not a significant effect of Gender (P = .74) or a significant Group × Gender interaction (P = .91). Consequently, Gender was dropped from further analyses.

Group Differences in Speech-Related N1 Suppression

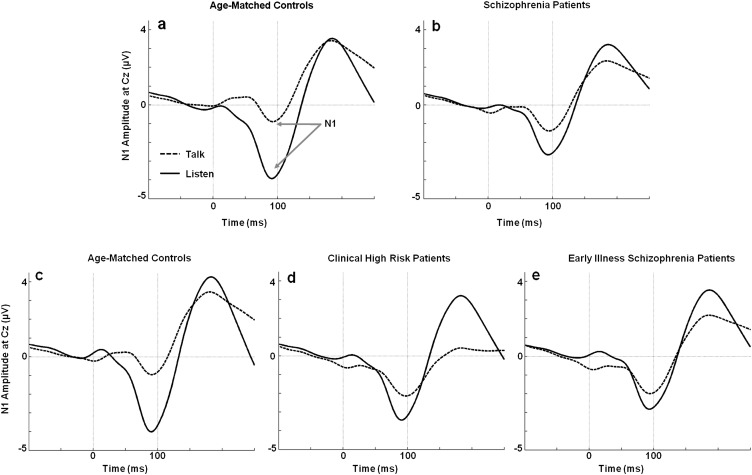

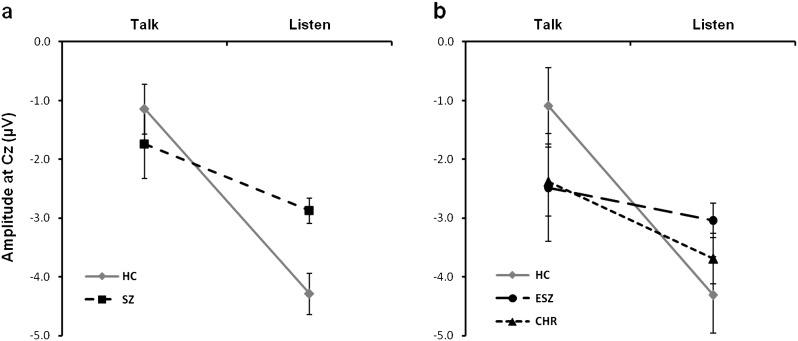

The grand average ERP waveforms showing the N1 for Talk and Listen conditions in each group are presented in figure 1. Mean N1 amplitudes for Talk and Listen conditions are plotted in figure 2. Inspection of Talk/Listen waveforms reveals reduced N1 during Talk relative to Listen conditions in the HC group, with attenuation of this effect in the patient groups. N1 Talk-Listen difference scores were used in the group analyses (see table 2).

Fig. 1.

Grand average event-related potential (ERP) waveforms for Talk and Listen conditions. ERP waveforms for Talk and Listen conditions show the N1 component during the Talk (dotted line) and Listen (solid line) conditions. (a) The N1 amplitude during Talk is reduced relative to Listen in healthy controls. (b) This effect is attenuated in the schizophrenia patients. (c) The N1 amplitude during Talk is reduced relative to Listen in a healthy control group age matched to (d) clinical high-risk, and (e) early illness schizophrenia patients.

Fig. 2.

N1 amplitude (mean and SE) for Talk and Listen conditions. Line graphs show group means and SEs for N1 amplitude assessed during Talk and Listen conditions. (a) Normal speech-related N1 suppression is shown in healthy controls (HC; solid line; Talk: M = −1.1, SE = 0.4; Listen: M = −4.3, SE = 0.3), while the flatter slope indicates reduced N1 suppression in schizophrenia patients (SZ; dashed line; Talk: M = −1.7, SE = 0.6; Listen: M = −2.9, SE = 0.2). In (b), clinical high-risk patients (CHR; dotted line; Talk: M = −2.4, SE = 0.6; Listen: M = −3.7, SE = 0.4) show a slope that is intermediate to age-matched healthy controls (HC; solid line; Talk: M = −1.1, SE = 0.7; Listen: M = −4.3, SE = 0.6) and early illness schizophrenia patients (ESZ; dashed line; Talk: M = −2.5, SE = 0.9; Listen: M = −3.0, SE = 0.3). All amplitude values are given in microvolts (μV).

Table 2.

Group Analyses for Speech-Related N1 Suppression across SZ and HC and in ESZ, CHR, and HC

| t-test Results (HC and SZ)a | Cohen’s d | df | t/F | P value |

| Group effect | 0.428 | 150 | 2.64 | .009 |

| ANOVA Results (HC, CHR, and ESZ)b | ||||

| Group effect | 2,109 | 3.29 | .041 | |

| Post hoc Tukey-Kramer Tests | ||||

| HC vs ESZ | 0.541 | .037 | ||

| HC vs CHR | 0.463 | .193 | ||

| CHR vs ESZ | 0.162 | .763 |

Note: SZ, Schizophrenia patients; HC, Healthy Control; ESZ, Early Illness Schizophrenia; CHR, Clinical High-Risk.

Independent Samples t test comparing SZ and age-matched HC groups on N1 Talk-Listen difference scores. Significance based on alpha = .05, 2-tailed.

One-way ANOVA comparing ESZ, CHR, and age-matched HC groups on N1 Talk-Listen difference scores. Significance based on alpha = .05, 2-tailed.

Schizophrenia Patients vs HCs

As previously reported,24 the full SZ sample showed a significantly attenuated speech-related N1 suppression effect compared with age-matched HC (figures 1a, b and 2a).

CHR Patients vs ESZ Patients vs HCs

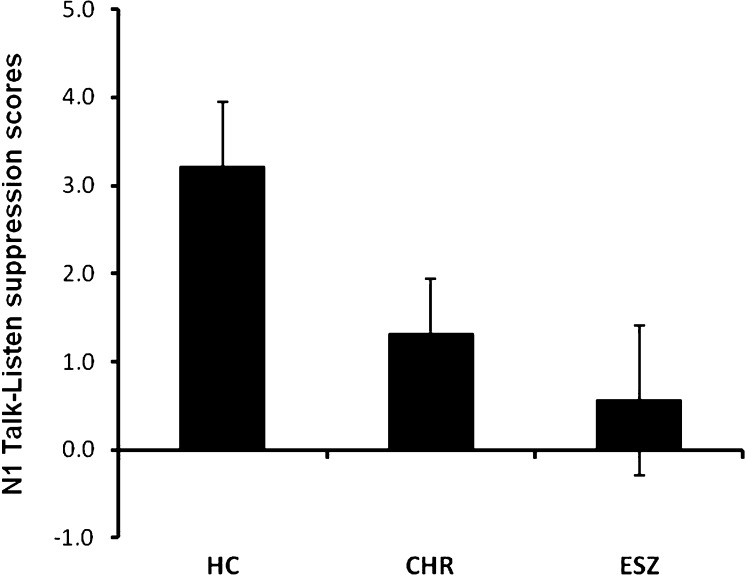

The one-way ANOVA showed a significant main effect of Group for speech-related N1 suppression (figures 1c–e and 2b). As can be seen in figure 3, N1 Talk-Listen suppression scores are reduced in the ESZ relative to the HC group (post hoc contrast: P = .037). However, CHR patients showed intermediate speech-related N1 suppression scores and did not significantly differ from either group (post hoc contrasts: CHR vs HC: P = .193; CHR vs ESZ: P = .763). Given the marginal age difference between Groups, the one-way ANOVA was repeated using age-corrected N1 suppression difference z scores, but the pattern of findings was unchanged.

Fig. 3.

N1 Talk-Listen difference scores. Mean (±SE) N1 Talk-Listen difference scores (in microvolts) for the age-matched healthy control group, clinical high-risk, and early illness schizophrenia patients.

Effects of Normal Aging on ERP Measures

There were no significant associations between age and speech-related N1 suppression scores in the full HC sample (r = .07, P = .58).

Group Differences in N1 During Listening

The full SZ sample showed a significantly reduced N1 amplitude during Listen (t 150 = -3.46, P < .001), consistent with the literature.39 However, the one-way ANOVA comparing ESZ and CHR to their age-matched controls did not reveal a main effect of Group (F 2, 109 = 1.96, P = .14); post hoc analysis also failed to find any pairwise group differences on this measure.

Correlational Analyses With Duration of Illness

Because duration of illness was significantly related to age in the full SZ sample (r = .94, P < .001), age-corrected N1 Talk-Listen difference z scores were used to assess the effects of illness duration, as described in the Methods. Illness duration was not significantly correlated with age-corrected N1 suppression z scores (r = .16, P = .18), indicating that the degree of speech-related N1 abnormality within the full SZ sample was stable over increasing illness duration.

Correlational Analyses With Clinical Ratings

PANSS positive and negative symptom subscales were not significantly correlated with N1 Talk-Listen difference scores in the full SZ sample. Similarly in the CHR patients, SOPS positive and negative symptom subscales were not significantly correlated with N1 Talk-Listen difference scores.

Discussion

Using a Talk-Listen paradigm, we examined speech-related suppression of the auditory N1 ERP component, a phenomenon that we9 , 20 – 24 and others,10 , 11 have interpreted as reflecting the action of a corollary discharge mechanism. Previously, we showed that this N1 suppression during speech was diminished in chronic schizophrenia9 , 20 – 24 consistent with predictions of corollary discharge dysfunction in the disorder.17 , 18 As in previous reports,9 , 15 , 24 we found diminished speech-related N1 suppression in this new sample of schizophrenia patients.

One aim of this study was to assess speech-related N1 suppression in patients early in their illness. The current study extends our previous findings by showing, for the first time, that abnormal suppression of N1 during talking is present in schizophrenia patients in the first 2.5 years of their illness and is not due to chronicity-related clinical sequelae of the illness.

Because we studied patients across a wide range of illness durations, we were able to extend the literature by showing that speech-related N1 suppression abnormalities are not affected by illness duration. That is, abnormal N1 suppression is not progressive and is evident before many of the sequelae of chronic illness emerge (eg, chronic disability and medication exposure, long-standing social and occupational dysfunction). This question has not been previously addressed in studies of corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia.9 , 15 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 40

In addition, the broad age range represented in our HC sample allowed us to examine the effects of normal brain maturation and aging from adolescence through adulthood on speech-related N1 suppression. We found no significant age effects, suggesting that this putative corollary discharge mechanism is present by adolescence and shows no further age-related changes into midlife.

Another aim of this study was to assess patients at CHR for psychosis. We found N1 suppression values that are intermediate to the suppression observed in HCs and early illness patients. In fact, CHR patients could not be statistically distinguished from either the HC or the early illness comparison groups. This pattern of intermediate effects is likely due to the heterogeneity of clinically high-risk patients and the fact that about one-third of them will convert to schizophrenia.30 Whether attenuated N1 suppression during speech predicts conversion to psychosis in clinically high-risk patients awaits longitudinal follow-up data, which are being collected in our lab.

Attenuated speech-related N1 suppression was not related to positive or negative symptoms in early illness or CHR patients. This finding is consistent with some,24 but not all,22 , 23 of our prior efforts to relate abnormal speech-related N1 suppression to symptoms. It is worth noting, however, that other studies have found relationships between psychotic symptoms to behavioral manifestations of corollary discharge failures.40 At least 2 factors work against finding relationships: First, medication can decouple the symptoms from the underlying neurobiology that enable the symptoms to manifest during exacerbations. Second, the symptom assessment interview is a blunt instrument, dependent on the patient to articulate features of the symptom and the clinician to hear what the patient is saying.

This study demonstrates that putative corollary discharge dysfunction during speech occurs early in schizophrenia, before the inevitable sequelae of chronic illness and remains stable over the course of the illness. Whether the intermediate values observed for the patients clinically at high-risk for developing psychosis is due to the ultimate conversion of some in this group depends on longitudinal studies of this cohort.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01MH076989, K02MH067967).

Acknowledgments

Drs Perez, Ford, Loewy, Stuart, Vinogradov, and Mathalon and Mr Roach report no competing interests. For researchers interested in gaining further insight into FASTER processing methods, you may subscribe to the “Faster-eeg-list” mailing list at: Faster-eeg-list@lists.sourceforge.net or https://lists.sourceforge.net/lists/listinfo/faster-eeg-list. To gain access to a variety of EEGLAB news lists, you may subscribe here: http://sccn.ucsd.edu/eeglab/eeglabmail.html. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1.Weiskrantz L, Elliott J, Darlington C. Preliminary observations on tickling oneself. Nature. 1971;230:598–599. doi: 10.1038/230598a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolpert DM, Ghahramani Z, Jordan MI. An internal model for sensorimotor integration. Science. 1995;269:1880–1882. doi: 10.1126/science.7569931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crapse TB, Sommer MA. Corollary discharge across the animal kingdom. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:587–600. doi: 10.1038/nrn2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suga N, Schlegel P. Neural attenuation of responses to emitted sounds in echolocating rats. Science. 1972;177:82–84. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4043.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sperry RW. Neural basis of the spontaneous optokinetic response produced by visual inversion. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1950;43:482–489. doi: 10.1037/h0055479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Holst E, Mittelstaedt H. The Reafference Principle. Interaction Between the Central Nervous System and the Periphery. In Selected Papers of Erich von Holst: The Behavioural Physiology of Animals and Man (From German) London, UK: Methuen; 1950. pp. 39–73. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creutzfeldt O, Ojeman G, Lettich E. Neuronal activity in the human lateral temporal lobe. II Responses to the subject's own voice. Exper Brain Res. 1989;77:476–489. doi: 10.1007/BF00249601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliades SJ, Wang X. Neural substrates of vocalization feedback monitoring in primate auditory cortex. Nature. 2008;453:1102–1106. doi: 10.1038/nature06910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Heinks T, Kalba S, Faustman WO, Roth WT. Neurophysiological evidence of corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2069–2071. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houde JF, Nagarajan SS, Sekihara K, Merzenich MM. Modulation of the auditory cortex during speech: an MEG study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2002;14:1125–1138. doi: 10.1162/089892902760807140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curio G, Neuloh G, Numminen J, Jousmaki V, Hari R. Speaking modifies voice-evoked activity in the human auditory cortex. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000;9:183–191. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(200004)9:4<183::AID-HBM1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford JM, Roach BJ, Mathalon DH. Assessing corollary discharge in humans using noninvasive neurophysiological methods. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1160–1168. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pantev C, Bertrand O, Eulitz C, et al. Specific tonotopic organizations of different areas of the human auditory cortex revealed by simultaneous magnetic and electric recordings. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;94:26–40. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)00209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naatanen R, Picton T. The N1 wave of the human electric and magnetic response to sound: a review and an analysis of the component structure. Psychophysiology. 1987;24:375–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1987.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinks-Maldonado TH, Mathalon DH, Gray M, Ford JM. Fine-tuning of auditory cortex during speech production. Psychophysiology. 2005;42:180–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson JH. Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinberg I. Efference copy and corollary discharge: implications for thinking and its disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1978;4:636–640. doi: 10.1093/schbul/4.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frith CD. The positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia reflect impairments in the perception and initiation of action. Psychol Med. 1987;17:631–648. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shergill SS, Samson G, Bays PM, Frith CD, Wolpert DM. Evidence for sensory prediction deficits in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2384–2386. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Kalba S, Whitfield S, Faustman WO, Roth WT. Cortical responsiveness during inner speech in schizophrenia: an event-related potential study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1914–1916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Kalba S, Whitfield S, Faustman WO, Roth WT. Cortical responsiveness during talking and listening in schizophrenia: an event-related brain potential study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:540–549. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford JM, Roach BJ, Faustman WO, Mathalon DH. Synch before you speak: auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:458–466. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinks-Maldonado TH, Mathalon DH, Houde JF, Gray M, Faustman WO, Ford JM. Relationship of imprecise corollary discharge in schizophrenia to auditory hallucinations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:286–296. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford JM, Gray M, Faustman WO, Roach BJ, Mathalon DH. Dissecting corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:522–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindner A, Thier P, Kircher TT, Haarmeier T, Leube DT. Disorders of agency in schizophrenia correlate with an inability to compensate for the sensory consequences of actions. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1119–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ford JM, Roach BJ, Faustman WO, Mathalon DH. Out-of-synch and out-of-sorts: dysfunction of motor-sensory communication in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams LM, Whitford TJ, Gordon E, Gomes L, Brown KJ, Harris AW. Neural synchrony in patients with a first episode of schizophrenia: tracking relations with grey matter and symptom profile. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2009;34:21–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Rosen JL, et al. Prospective diagnosis of the initial prodrome for schizophrenia based on the Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes: preliminary evidence of interrater reliability and predictive validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:863–865. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yung AR, McGorry PD. The initial prodrome in psychosis: descriptive and qualitative aspects. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1996;30:587–599. doi: 10.3109/00048679609062654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cannon TD, Cadenhead K, Cornblatt B, et al. Prediction of psychosis in youth at high clinical risk: a multisite longitudinal study in North America. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:28–37. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brockhaus-Dumke A, Schultze-Lutter F, Mueller R, et al. Sensory gating in schizophrenia: P50 and N100 gating in antipsychotic-free subjects at risk, first-episode, and chronic patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez VB, Ford JM, Woods SW, et al. Error monitoring dysfunction across the illness course of schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0025487. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cadenhead KS, Light GA, Shafer KM, Braff DL. P50 suppression in individuals at risk for schizophrenia: the convergence of clinical, familial, and vulnerability marker risk assessment. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1504–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kay S, Opler L. The positive-negative dimension in schizophrenia: its validity and significance. Psychiatr Dev. 1987;5:79–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nolan H, Whelan R, Reilly RB. FASTER: fully automated statistical thresholding for EEG artifact rejection. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;192:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leonowicz Z, Karvanen J, Shishkin SL. Trimmed estimators for robust averaging of event-related potentials. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;142:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kayser J, Tenke CE. Optimizing PCA methodology for ERP component identification and measurement: theoretical rationale and empirical evaluation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2307–2325. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfefferbaum A, Lim KO, Zipursky RB, et al. Brain gray and white matter volume loss accelerates with aging in chronic alcoholics: a quantitative MRI study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16:1078–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosburg T, Boutros NN, Ford JM. Reduced auditory evoked potential component N100 in schizophrenia–a critical review. Psychiatry Res. 2008;161:259–274. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blakemore SJ, Smith J, Steel R, Johnstone CE, Frith CD. The perception of self-produced sensory stimuli in patients with auditory hallucinations and passivity experiences: evidence for a breakdown in self-monitoring. Psychol Med. 2000;30:1131–1139. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]