Abstract

Under physiological conditions, most neurons keep glycogen synthase (GS) in an inactive form and do not show detectable levels of glycogen. Nevertheless, aberrant glycogen accumulation in neurons is a hallmark of patients suffering from Lafora disease or other polyglucosan disorders. Although these diseases are associated with mutations in genes involved in glycogen metabolism, the role of glycogen accumulation remains elusive. Here, we generated mouse and fly models expressing an active form of GS to force neuronal accumulation of glycogen. We present evidence that the progressive accumulation of glycogen in mouse and Drosophila neurons leads to neuronal loss, locomotion defects and reduced lifespan. Our results highlight glycogen accumulation in neurons as a direct cause of neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Drosophila, glucose metabolism, glycogen, Lafora disease, neurodegeneration

INTRODUCTION

In the animal kingdom, glycogen is the main storage form of glucose, and glycogen synthase (GS) is the only enzyme able to synthesize it. The genes GYS1 and GYS2 encode for the two vertebrate isoforms of GS. GYS2 is expressed only in the liver, and GYS1, encoding for muscle glycogen synthase (MGS), is expressed in most tissues including the brain (Kaslow et al, 1985). MGS is regulated by phoshorylation in the N- and C-terminal domains of the enzyme. Phosphorylation by several kinases, including glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), induces the inactivation of the enzyme (Bouskila et al, 2008; Roach et al, 1998). High levels of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) allosterically activate MGS even when the enzyme is phosphorylated, this being the primary mechanism by which insulin promotes glycogen accumulation in muscle (Bouskila et al, 2010). In the brain, glycogen is stored in astrocytes (Brown, 2004; Brown & Ransom, 2007; Cataldo & Broadwell, 1986; Wender et al, 2000) and neuronal MGS is kept in an inactive state (Vilchez et al, 2007). However, in some neurodegenerative diseases like Lafora disease (LD), glycogen accumulation is observed in neurons (OMIM254780).

Lafora disease (epilepsy, progressive myoclonus type 2, EPM2) is an inherited autosomal recessive disorder associated with mutations in the EPM2A and EPM2B genes (Ianzano et al, 2005). EPM2A encodes for laforin, a dual-specificity protein phosphatase with a functional carbohydrate-binding domain (Ganesh et al, 2000), while EPM2B encodes for malin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase (Gentry et al, 2005). Malin and laforin act as a complex to target MGS for degradation. Protein targeting to glycogen (PTG), a protein phosphatase-1 regulatory subunit that promotes the activation of MGS by dephosphorylation, is also targeted by the malin/laforin complex for degradation (Vilchez et al, 2007). Epm2b and Epm2a knock-out mice, like LD patients, show progressive accumulation of glycogen in neuronal tissues (Ganesh et al, 2002; Valles-Ortega et al, 2011).

In spite of the long recognized aberrant accumulation of glycogen in LD and the fact that PTG depletion rescues the histological and behavioural phenotype of Epm2a knock-out mice (Turnbull et al, 2011), there is still no direct evidence as to whether the accumulation of glycogen is the cause of the disease. Because malin, laforin and also PTG are involved in cellular processes other than the regulation of MGS, increased stress of the endoplasmic reticulum, reduced autophagy and reduced clearance of misfolded toxic proteins through the ubiquitin–proteasome system have been proposed as alternative underlying causes of LD (Aguado et al, 2010; Criado et al, 2011; Puri & Ganesh, 2010; Vernia et al, 2009). In the present study, we generated mouse and fly models expressing a form of MGS resistant to inactivation, in which nine regulatory serine residues were mutated to alanine. We present evidence that accumulation of glycogen in mouse and Drosophila neurons has deleterious consequences and leads to neuronal loss, locomotion defects and reduced lifespan.

RESULTS

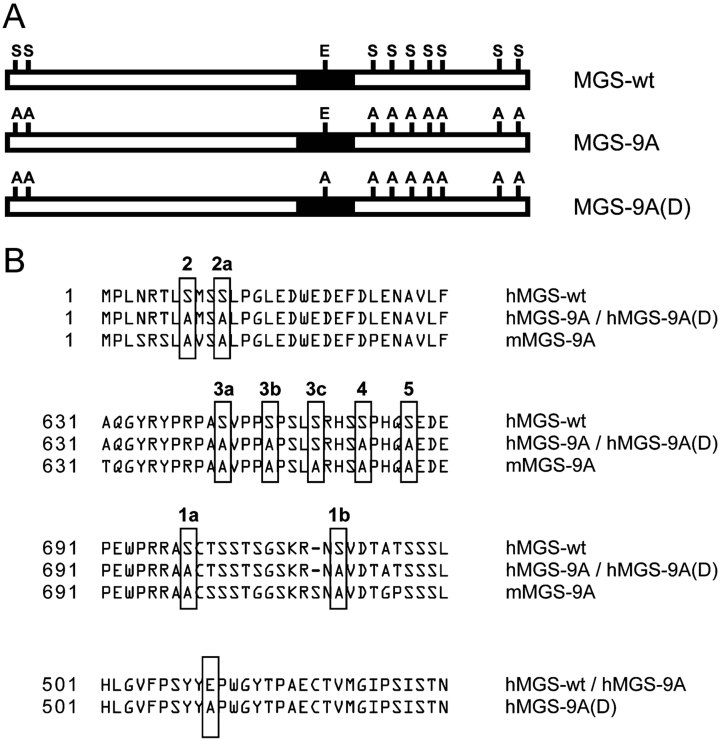

Neurons express MGS but have a high capacity to inactivate it. When neuron primary cultures are forced to express wild-type MGS, the protein is highly phosphorylated and thus completely inactivated, thereby preventing glycogen production (Vilchez et al, 2007). In order to circumvent this type of regulation, we generated a mutant form of human MGS (hMGS) that cannot be inactivated by phosphorylation (Cid et al, 2005). Nine regulatory serines in hMGS (sites 2 and 2a in the N-terminus, and sites 3a, 3b, 3c, 4, 5, 1a and 1b in the C-terminus) were mutated to alanine, thus generating a non-inactivatable form of hMGS called hMGS-9A (Fig 1A and B). We also generated a mutant form of hMGS-9A called hMGS-9A(D), which carries a point mutation in its active site (E510A, Fig 1A and B) (Cid et al, 2000). hMGS-9A(D) is catalytically inactive (dead, D) and unable to produce glycogen in spite of containing the nine serine residues mutated to alanine.

Figure 1. Diagram of MGS and MGS mutants.

- Schematic representation of wild-type MGS (MGS-wt) and the non-inactivatable (MGS-9A) and catalytically inactive (MGS-9A(D)) mutants. Regulatory serines and one glutamic residue in the catalytic site are shown.

- Alignment of MGS and mutants showing regulatory serine residues in MGS mutated to alanine to generate the non-inactivatable human (hMGS-9A), non-inactivatable mouse (mMGS-9A) and catalytically inactive (hMGS-9A(D)) mutants as well as the glutamic residue in the catalytic site of hMGS-9A(D).

A form of hMGS resistant to inactivation leads to accumulation of glycogen in Drosophila neurons

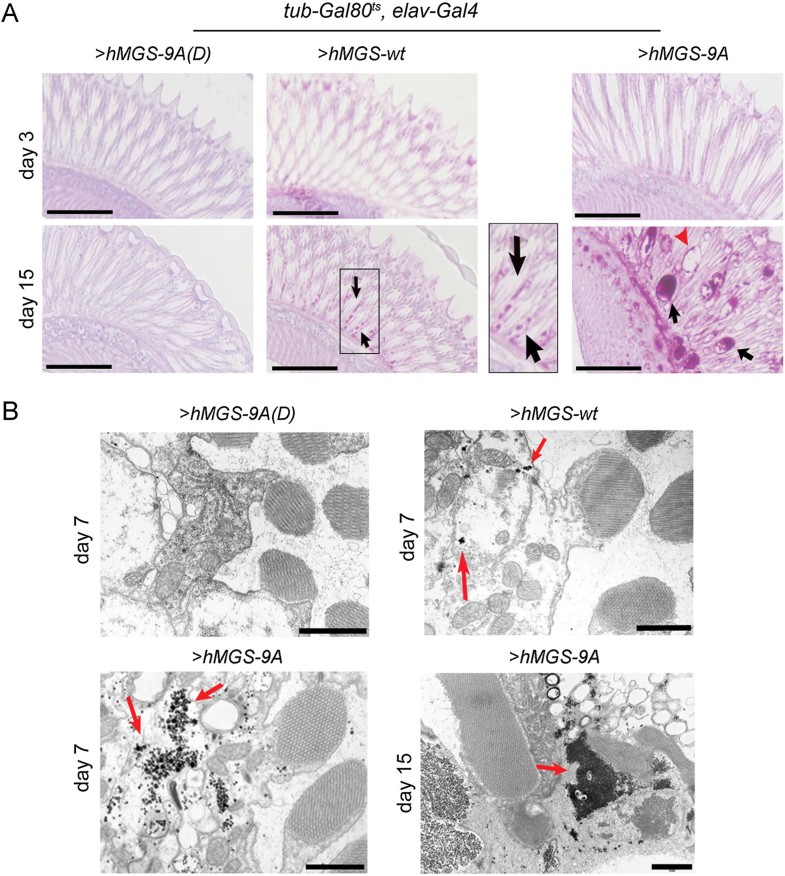

We generated a fly model system to drive the expression of hMGS-9A, hMGS-9A(D) and a wild-type form of hMGS (hMGS-wt) in neuronal tissues. To control gene expression in time and space, we used the Gal4/UAS system (Brand & Perrimon, 1993; Elliott & Brand, 2008) combined with the thermo-sensitive version of Gal80 (Gal80ts), a repressor of Gal4 protein activity (McGuire et al, 2004). Larvae carrying the pan-neural elav-Gal4 driver, the tub-Gal80ts construct and the UAS-transgene (UAS-hMGS-wt, UAS-hMGS-9A or UAS-hMGS-9A(D)) were raised at 18°C and transferred to 29°C immediately after hatching as adults. In order to confirm that the different forms of hMGS were expressed in an equal concentration in fly neurons, we quantified the amount of protein expressed in brains by Western blot. The three forms showed equal expression levels 24 h after transfer to the permissive temperature (Supporting Information Fig 1). hMGS showed a differential mobility when compared to hMGS-9A and hMGS-9A(D), most probably as a consequence of its different phosphorylation state, hence different activation state. Glycogen accumulation was monitored by two qualitative methods: periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining and electron microscopy (EM). We centred our attention on adult photoreceptors. PAS-positive (pink) neuronal cells were observed in 15-day-old hMGS-9A-expressing flies, and retinas presented signs of spongiosis (Fig 2A). Surprisingly, some staining was also observed in hMGS-wt-expressing neurons of 15-day-old flies, suggesting that some hMGS escapes downregulation by phosphorylation (Supporting Information Fig 1). As expected, hMGS-9A(D)-expressing photoreceptors were not stained even after 40 days at the permissive temperature (unpublished observation). We also performed EM after 7 days of transgene expression in order to visualize glycogen granules in neuronal tissues. Scattered glycogen granules were observed in hMGS-wt-expressing neurons (Fig 2B), whereas in age-matched hMGS-9A-expressing neurons these granules were more conspicuous (Fig 2B). No glycogen granules were observed in neurons expressing hMGS-9A(D) (Fig 2B). Fifteen-day-old flies expressing hMGS-9A had electrodense structures corresponding to excessive glycogen accumulation (Fig 2B).

Figure 2. Glycogen accumulation in Drosophila neurons.

- PAS (pink)/haematoxylin (blue) staining of retina sections of tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4 adult flies driving expression of UAS-hMGS-9A(D) (left), UAS-hMGS-wt (middle) and UAS-hMGS-9A (right) transgenes at 29°C during 3 (upper raw) or 15 days (bottom raw). Black arrows point to PAS positive staining and red arrowhead to the disruption of the tissue. Scale bar, 50 µm. The images are representative of staining performed in four to seven individuals per condition.

- Scanning electron microscopy of retina sections of tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4 adult flies driving expression of UAS-hMGS-9A(D), UAS-hMGS-wt and UAS-hMGS-9A (right) transgenes at 29°C during 7 or 15 days. Red arrows point to glycogen granule-like structures. Scale bar, 1 µm. The images are representative of staining performed in four to five individuals per condition.

Accumulation of glycogen in Drosophila neurons leads to lifespan and locomotion defects

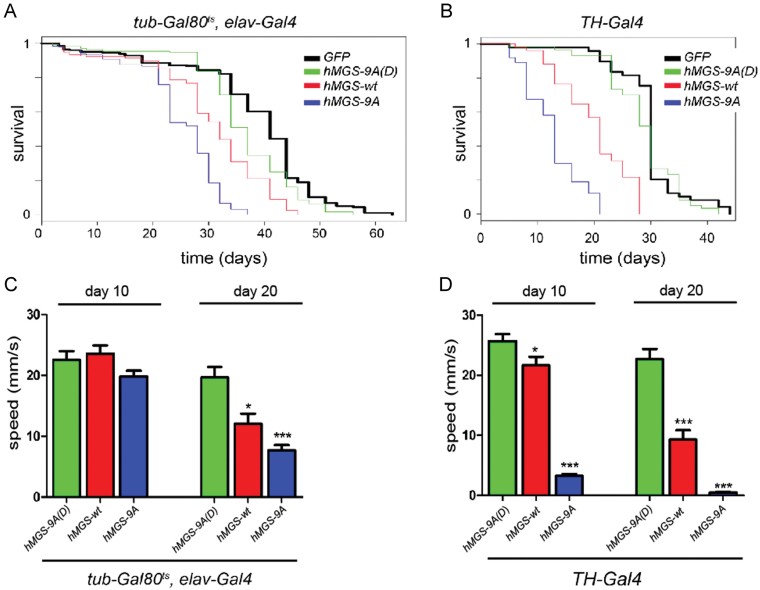

So far, our data indicate that hMGS-9A and to a lesser extent hMGS-wt have the capacity to drive glycogen accumulation when expressed in Drosophila neurons. We next analyzed the impact of these transgenes on adult lifespan and locomotion. Interestingly, pan-neuronal expression of hMGS-9A produced a marked decrease in lifespan (mean survival = 25.5 days, n = 195, p < 1E-323, maximum survival = 35 days) when compared to control green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing flies (mean survival = 39.2 days, n = 282, maximum survival = 60 days Fig 3A). In contrast, hMGS-wt induced a moderate reduction (mean survival = 31.2 days, n = 232, p < 1E-323, maximum survival = 45 days) and hMGS-9A(D) caused only a slight decrease in lifespan (mean survival = 37, n = 173, p = 8.3E-06, maximum survival = 55 days) when compared to control GFP-expressing flies (Fig 3A). Similar results were obtained by driving transgene expression in dopaminergic TH (+) neurons with an independent Gal4 driver (TH-Gal4). Thus, expression of hMGS-9A in TH (+) neurons led to a dramatic shortening of adult lifespan (mean survival = 13.4, n = 74, p < 1E-323, maximum survival = 20 days) when compared to GFP-expressing flies (mean survival = 30.4, n = 49, maximum survival = 44 days; Fig 3B) whereas hMGS-wt caused a milder defect in this parameter (mean survival = 20.6, n = 51, p = 5.55E-16, maximum survival = 28 days, Fig 3B). No lifespan defects were observed upon hMGS-9A(D) expression in TH (+) neurons (mean survival = 29.2, n = 60, p = 0.232, maximum survival = 41 days, Fig 3B). Interestingly, flies expressing hMGS-9A or hMGS-wt under the control of the elav-gal4 or TH-gal4 drivers showed locomotion defects when compared to hMGS-9A(D)-expressing flies, as monitored by measuring the mean speed in a climbing assay (Fig 3C and D). All together, these data indicate that expression of a non-inactivatable form of hMGS in Drosophila neuronal cells has the capacity to drive glycogen accumulation and induce lifespan and locomotion defects, and support the notion that it is the glycogen dose and hence the protein activity and not the accumulation of this protein in neurons that leads to neurodegeneration.

Figure 3. Lifespan and locomotion defects in adult flies.

- A,B. Survival assay of tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4 (A) and TH-Gal4 (B) adult flies driving expression of the following transgenes: UAS-mCD8-GFP (black); UAS-hMGS-9A(D) (green); UAS-hMGS-wt (red); UAS-hMGS-9A (blue). tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, UAS-mCD8-GFP (n = 282, µx = 39.2 max = 62); tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, UAS-hMGS-9A(D) (n = 173, µx = 37, p = 8.3E-06, max = 52); tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, UAS-hMGS-wt (red, n = 232, µx = 31.2, p < 1E-323, max = 46); tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, UAS-hMGS-9A (n = 195, µx = 25.5, p < 1E-323, max = 36). TH-Gal4; UAS-nlsGFP, mCD8::GFP (n = 49, µx = 30.4 max = 44); TH-Gal4; UAS-hMGS-9A(D), UAS-mCD8::GFP (n = 60, µx = 29.2, p = 0.232, max = 41); TH-Gal4; UAS-hMGS-wt, UAS-mCD8::GFP (n = 51, µx = 20.6, p = 5.55E-16, max = 33); TH-Gal4; UAS-hMGS-9A, UAS-mCD8::GFP (n = 74, µx = 13.4, p < 1E-323, max = 21). n = number of individuals per group, max = maximum lifespan (days), µx = mean survival (days) and p-value calculated by logrank test compared to GFP control.

- C,D. Climbing assay: speed (in mm/s) of tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4 (C) and TH-Gal4 (D) adult flies driving expression of the following transgenes: UAS-hMGS-9A(D) (green); UAS-hMGS-wt (red); UAS-hMGS-9A (blue) during 10 or 20 days. Mean speed ± s.e.m. (10 days): tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, hMGS-9A(D) = 22.52 ± 1.5 (n = 10), tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, hMGS-9A = 19.79 ± 0.966 (n = 17, p = 0.121), tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, hMGS-wt = 23.60 ± 1.363 (n = 13, p = 0.6028). Mean speed (20 days): tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, hMGS-9A(D) = 19.69 ± 1.719 (n = 14), tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, hMGS-9A = 7.643 ± 0.89 (n = 9, p = 6.06E-06), tub-Gal80ts, elav-Gal4, hMGS-wt = 12.04 ± 1.686 (n = 6, p = 0.0158). Mean speed ± s.e.m. (10 days): TH-Gal4; hMGS-9A(D) = 25.68 ± 1.228 (n = 14), TH-Gal4; hMGS-9A = 3.293 ± 0.3006 (n = 14, p = 8.87E-12), TH-Gal4; hMGS-wt = 21.63 ± 1.464 (n = 15, p = 0.0424). Mean speed (20 days): TH-Gal4; hMGS-9A(D) = 22.71 ± 1.666 (n = 12), TH-Gal4; hMGS-9A = 0.4436 ± 0.1722 (n = 10), p = 3,18E-08), TH-Gal4; hMGS-wt = 9.329 ± 1.511 (n = 14, p = 3.92E-06). p-Value was calculated by Student's t-test compared to age matched hMGS-9A(D). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

We observed that hMGS-wt expression caused milder effects on adult lifespan and locomotion (Fig 3). In contrast, pan-neuronal overexpression of Drosophila GS (dGS), which has low sequence similarity to hMGS, was not able to induce glycogen accumulation or cause lifespan defects (mean survival = 34.9, n = 62, p = 0.233, maximum survival = 50 days) when compared to control GFP-expressing flies (mean survival = 36.1, n = 75, maximum survival = 56 days, Supporting Information Fig 2). These data support the notion that hMGS-wt, but not dGS, escapes downregulation by phosphorylation in flies, probably because of sequence differences between the hMGS and dGS isoforms as well as differences in the regulatory machineries between Drosophila and mammalian neurons.

A form of mMGS resistant to inactivation leads to accumulation of glycogen in mouse neurons

We also generated a mouse model conditionally expressing a non-inactivatable form of murine MGS called mMGS-9A (Fig 1). Expression of mMGS-9A was based on the Cre-lox technology. The mMGS-9A cDNA was expressed under the control of the ubiquitous CAG promoter (CMV immediate early enhancer/chicken β-actin promoter fusion) and a loxP-flanked transcription Stop cassette was included between the CAG promoter and the mMGS-9A cDNA to drive Cre recombinase-dependent expression of mMGS-9A (Supporting Information Fig 3A). The resulting mouse line can be bred with a variety of Cre recombinase-expressing animals to obtain tissue- or time-specific activation of the expression cassette. The mMGS-9A-containing cassette was introduced into the Hprt locus in the X chromosome by homologous recombination, thereby avoiding the uncontrolled outcomes of random integration. Due to female X chromosome inactivation, the following studies were conducted in male animals.

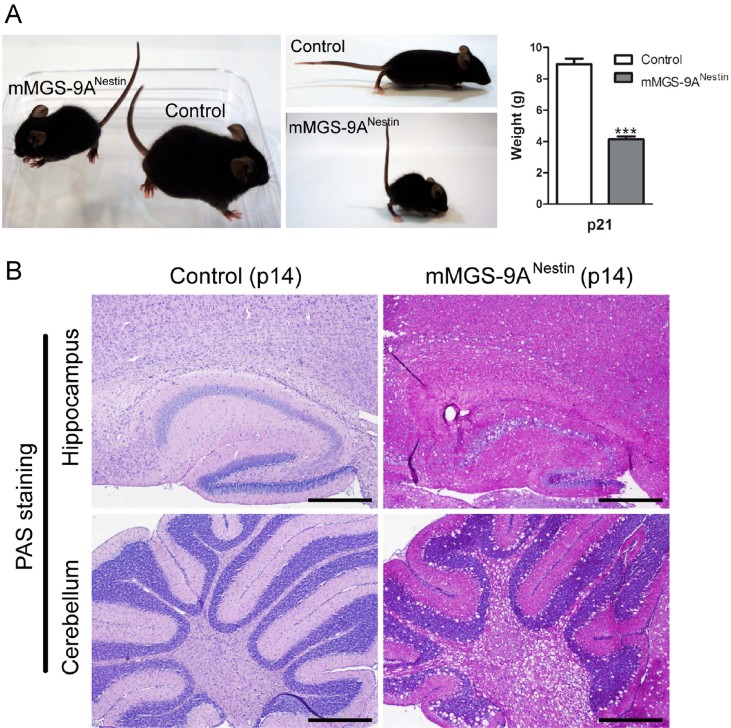

Our first aim was to drive the expression of mMGS-9A throughout the whole nervous system. For this purpose, we crossed an mMGS-9A conditional transgenic strain with Nestin-Cre transgenic mice to generate mMGS-9ANestin mice. The nestin promoter induces Cre recombinase expression in neuronal and glia cell precursors by embryonic day 11 (Tronche et al, 1999). mMGS-9ANestin mice presented a dramatic phenotype. Three-week-old (p21) mice showed signs of pain and distress, such as low weight (Fig 4B), unkempt appearance, abnormal posture, decreased movement and twitching, and thus had to be sacrificed. Analysis of 2-week-old (p14) mMGS-9ANestin animals showed a dramatic alteration in brain morphology with clear signs of spongiosis and robust neuronal PAS staining (Fig 4A). An increase in glycogen levels, GS activity and activity ratio (−G6P/+G6P, a measure of the degree of activation of the enzyme) was evident in whole brain extracts from mMGS-9ANestin animals when compared to control individuals (Supporting Information Fig 3). Neurodegeneration in Epm2b KO mice (a model of LD) has been associated with the accumulation of insoluble glycogen (Valles-Ortega et al, 2011). Interestingly, glycogen in the insoluble fraction was also detected in mMGS-9ANestin mice but not in control individuals (Supporting Information Fig 3D). Given the strong phenotype of mMGS-9ANestin mice when compared to diseased Epm2b KO ones (Valles-Ortega et al, 2011), we compared the amount of mMGS protein in these two mouse models. Western blot analyses showed comparable but higher levels of mMGS protein in whole brain extracts from mMGS-9ANestin mice than in Epm2b KO individuals (Supporting Information Fig 3). Thus, mMGS-9ANestin mice model glycogen-induced neurodegeneration in a widespread and accelerated manner.

Figure 4. Severe phenotype upon ubiquitous neuronal expression of mMGS-9A.

- Weight deficit and abnormal posture in p21 mMGS-9ANestin mice compared to control animals (mean ± s.e.m., n = 7–10 individuals per group, p = 3.5E-08). p-Value was calculated by Student's t-test compared to age-matched controls. ***p < 0.001.

- PAS (pink)/haematoxylin (blue) staining of brain sections (hippocampus and cerebellum) of 2-week-old (p14) mMGS-9ANestin and control animals. Scale bars, 100 µm. The images are representative of staining performed in three individuals per condition.

Accumulation of glycogen in Purkinje cells leads to neuronal loss and locomotion defects

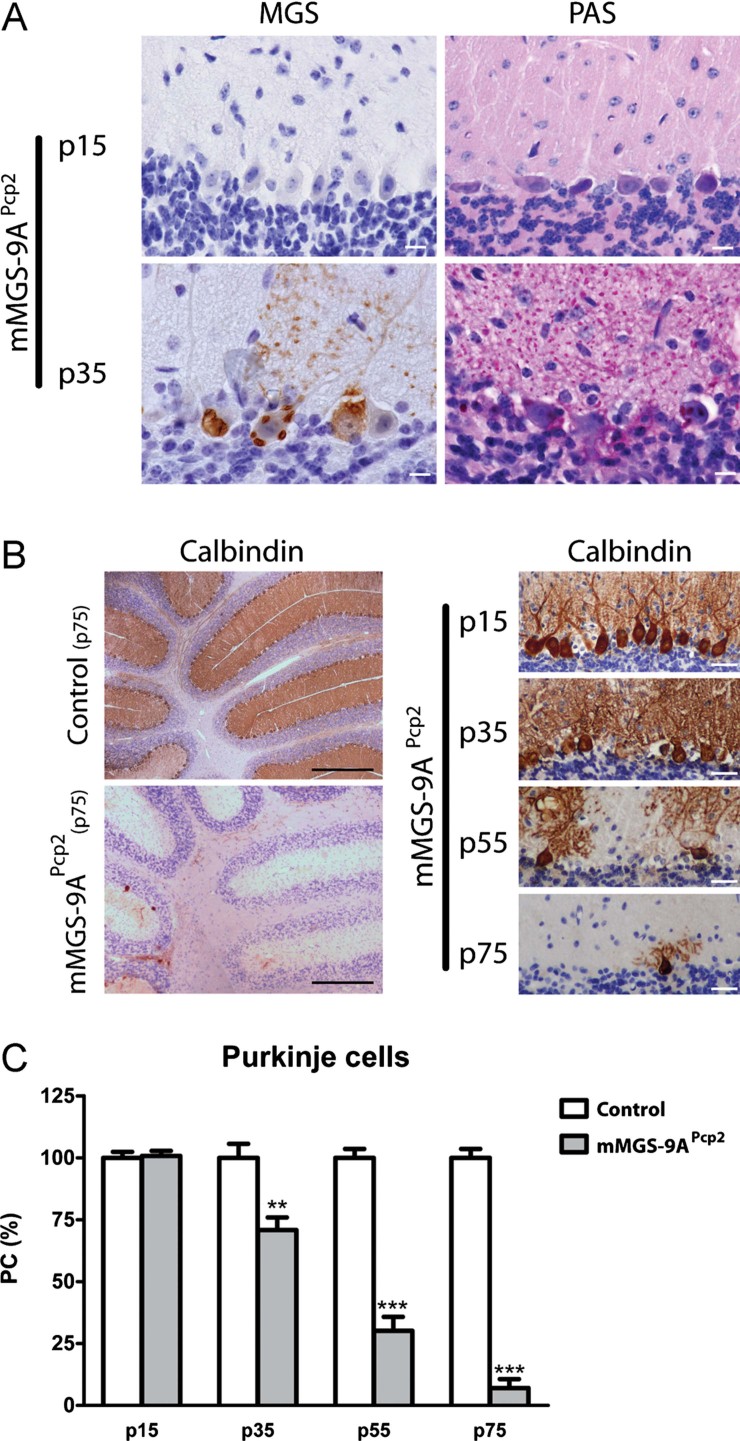

In order to produce a less severe phenotype, we generated a mouse model that expressed mMGS-9A only in a particular subset of neurons. For this reason, we crossed our conditional strain with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the control of the Pcp2 promoter (Barski et al, 2000) to generate mMGS-9APcp2 mice. The Pcp2 promoter drives the expression of Cre recombinase to Purkinje neurons, one of the neuron types affected in LD. We chose Purkinje cells (PCs) as a model for several reasons. They have a well-defined anatomic location and morphology, thus facilitating its identification and quantification, and alterations in PCs lead to ataxia, a functional phenotype that is also easy to detect and quantify. Importantly, Cre-expression in Pcp2-Cre mice is not fully established until the second to third week after birth (Barski et al, 2000; Schaefer et al, 2007). mMGS-9APcp2 mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratios and developed normally until adulthood. Whereas the expression of MGS protein was not detected in p15 mMGS-9APcp2 neurons, mMGS-9A-expressing Purkinje neurons of p35 animals showed detectable levels of MGS protein and robust accumulation of glycogen, as shown by PAS staining (Fig 5A). To evaluate the state of the PC layer, we immunolabelled brain slices at several ages with an antibody specific for calbindin (a PC marker, Fig 5B). Whereas the PC layer was unaffected in p15 animals, a 25% PC loss was observed in p35 mice. The degree of PC loss increased until PCs were virtually absent in p75 mMGS-9APcp2 animals (Fig 5B and C). Control littermates did not show PC loss.

Figure 5. Progressive loss of Purkinje neurons in mMGS-9A Pcp2 mice.

- PAS (pink) and haematoxylin (blue) staining of cerebellar sections of p15 and p35 mMGS-9APcp2 animals labelled to visualize MGS protein expression (brown). Scale bars, 10 µm. The images are representative of staining performed in four to five individuals per condition.

- Cerebellar sections of p15-p75 mMGS-9APcp2 animals labelled to visualize Purkinje cells by Calbindin protein expression (brown). Sections were also labelled with haematoxylin (blue). Scale bars, 500 µm (left) and 30 µm (right). The images are representative of staining performed in three to four individuals per condition.

- Quantification of the Purkinje cell density at several ages (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3–4 individuals per group, 6 fields per animal; p values: p15 = 0.79, p35 = 0.0093, p55 = 0.0007, p75 = 2.26E-07). p-Value was calculated by Student's t-test compared to age-matched controls. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

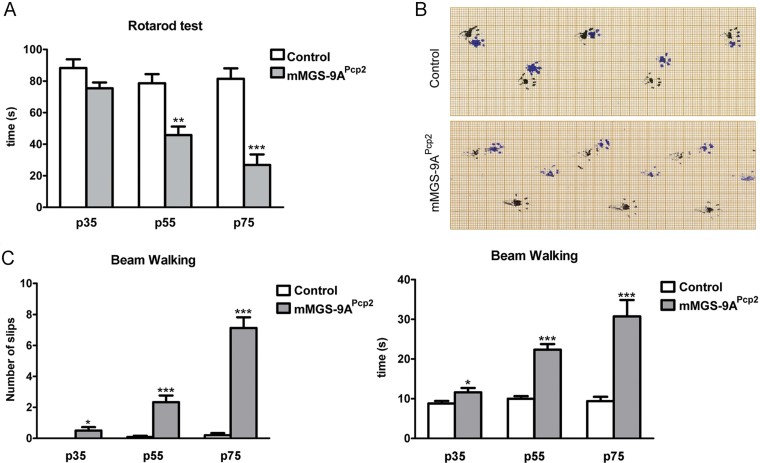

Extensive PC loss typically leads to ataxia. Ataxia was apparent by simple observation of p75 animals, as they presented tremor and altered gait. In order to quantify motor coordination at a range of ages in control and mMGS-9APcp2 animals, we performed several behavioural analyses, like the Rotarod test (Fig 6A), Footprint assay (Fig 6B) and Beam Walking test (Fig 6C). A mild motor coordination disturbance was observed in p35 mMGS-9APcp2mice. p55 animals showed clear ataxia, which was exacerbated in p75 animals. The chronology of these behavioural defects correlates with those seen in the histological studies.

Figure 6. Ataxia phenotype in mMGS-9APcp2 mice.

- Rotarod test. The time spent on the accelerating rotarod was measured (mean ± s.e.m., n = 6–11 individuals per group, 3 repetitions per individual; p values: (p35) p = 0.0685, (p55) p = 0.0019, (p75) p = 6.35E-05). p Values were calculated by Student's t-test compared to age-matched controls.

- Foot-print analysis. Footprints of p75 mMGS-9APcp2 and control mice are shown (black, front paws; blue, hind paws). The images are representative of tests performed with five individuals per condition.

- Beam Walking test. The time spent running on a balance beam and the number of hindpaw slips during this activity was measured (mean ± s.e.m., n = 8–12 individuals per group, 3 repetitions per individual; p values: (p35 slips) p = 0.038, (p55 slips) p = 0.00004, (p75 slips) p = 7.7E-09, (p35 time) p = 0.045, (p55 time) p = 8.7E-08, (p75 time) p = 4.6E-05). p Values were calculated by Student's t-test compared to age-matched controls. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

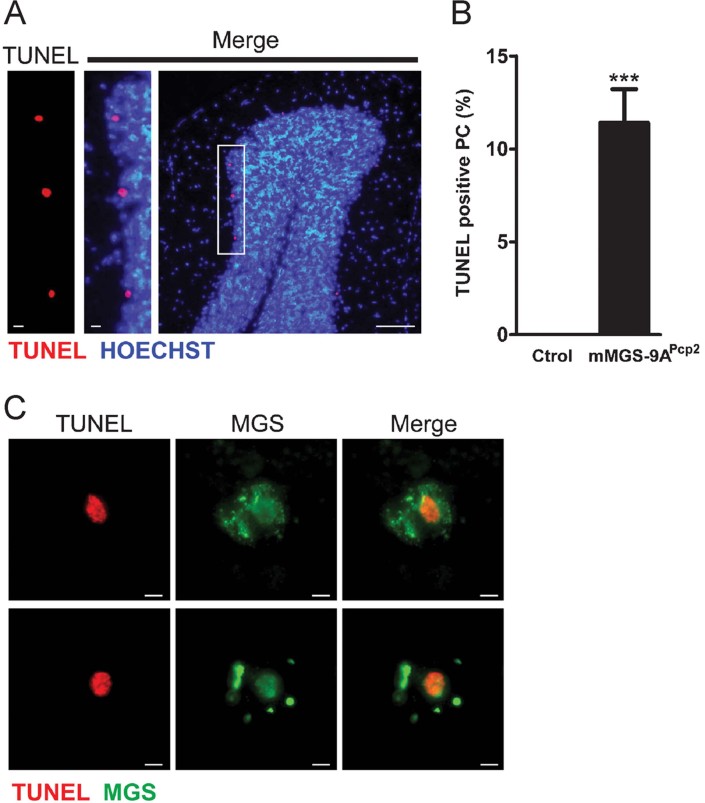

We previously presented evidence that primary cultured neurons undergo apoptosis when forced to accumulate glycogen (Vilchez et al, 2007). To analyze whether mMGS-9A-expressing PCs underwent apoptosis, we performed a TUNEL assay in brain slices of p35 mMGS-9APcp2 animals. We found TUNEL-positive cells in the PC layer (Fig 7A), and mMGS-9APcp2 cerebella showed TUNEL-positive staining in more than 10% of the PCs at p35, whereas TUNEL staining was absent in control cerebella (Fig 7B). mMGS-9APcp2 animals also expressed Cre and thus mMGS-9A in some cardiomyocytes. These cells were positively labelled by PAS staining but, interestingly, they were not positively labelled by TUNEL staining (Supporting Information Fig 4). These observations support the notion that neurons are particularly susceptible to glycogen accumulation.

Figure 7. TUNEL staining of Purkinje neurons in mMGS-9APcp2 mice.

- Cerebellar sections of p35 mMGS-9APcp2 animals labelled to visualize apoptotic cells in the Purkinje neuronal layer by TUNEL staining (red). Sections were also labelled with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars, 10 µm (left) and 100 µm (right).

- Quantification of the TUNEL positive cells (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 individuals per group, 6 fields per animal, p = 0.00027). p-Value was calculated by Student's t-test compared to age-matched controls. ***p < 0.001.

- TUNEL staining (red) and immunodetection of MGS expression (green) in two representative TUNEL-positive Purkinje neurons of p35 mMGS-9APcp2 animals. Scale bars, 10 µm.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of LD and the causal relationship between glycogen accumulation and neurodegeneration have remained elusive. Here we generated fly and mouse models to express in adult neurons a mutant form of MGS called MGS-9A that is resistant to inactivation by phosphorylation. We present the first in vivo evidence that increased MGS activity in adult neurons leads to the progressive accumulation of glycogen, neuronal loss, locomotion defects and reduced lifespan. Our results support the notion that glycogen accumulation contributes to LD and that it could also be the underlying cause of other diseases associated with glycogen accumulation, like adult polyglucosan body disease (OMIM263570) and Andersen disease (OMIM232500). Furthermore, glycogen deposits observed in other conditions, such as in diabetes (Bestetti & Rossi, 1980; Leel-Ossy, 1995; Moore et al, 1981; Powell et al, 1977; Tay & Wong, 1991), neurons under hypoxic or ischemic conditions (Ibrahim, 1972; Long et al, 1972), neurons adjacent to tumours (Koizumi et al, 1970), or ageing (Gertz et al, 1985), may also contribute to pathogenesis by causing neurodegeneration.

In Drosophila, the expression of hMGS-9A induced the accumulation of large glycogen deposits which correlated with a dramatic reduction in lifespan and clear locomotion defects. Interestingly, expression of a wild-type version of MGS led to mild glycogen accumulation and moderate changes in lifespan and locomotion, whereas expression of the Drosophila homolog of GS had no impact on the variables studied. Control flies expressing a catalytically dead form of MGS-9A did not show neuronal glycogen and had an almost normal lifespan. All together, these results support the idea that it is the glycogen dose, hence the protein activity and not its accumulation in adult neurons that leads to neurodegeneration.

Consistent with the phenotype observed in flies, expression of murine MGS-9A throughout the whole mouse nervous system of otherwise healthy animals led to the accumulation of large glycogen deposits and to dramatic changes in the behaviour of these animals and a shortening of their lifespan. The level of GS expression obtained in this model is substantial compared to the basal levels of GS expression in the brain, and even higher than the elevated levels observed in diseased Epm2b KO mice. The observation that each cell in the brain of the nestin-driven transgenic mice expresses the transgene, together with the high activity of the recombinant promoter, may account for such a dramatic increase in MGS and glycogen levels, and for the profound impact in the phenotype of the mice. Thus, we have generated a highly accelerated model of glycogen-induced neurodegeneration. This acceleration might also explain the fact that the main clinical observation of LD, namely myoclonus epilepsy, is not noticeable in these mice. Glycogen-induced neurodegeneration models address a specific aspect not only of LD but also of several other pathologies that course with neuronal glycogen accumulation. Myoclonus epilepsy pinpoints the cells or functions that are more susceptible to malin or laforin deficiency. Many other cells, tissues and functions are altered in LD patients and animal models, but their clinical relevance is obscured by the prominent and visible impact of epilepsy on the life of patients. It is interesting to note in this context that with the progression of the disease, LD patients also suffer a rapid cognitive decline, which results in dementia.

Purkinje neurons are affected in LD patients. Targeting MGS-9A to Purkinje mouse neurons led to ataxia and motor coordination disturbances, one of the clinical symptoms observed in LD patients. Moreover, Purkinje neurons expressing active MGS showed positive TUNEL staining suggesting that in vivo, like in vitro, there is a correlation between glycogen accumulation and neuronal apoptosis. Energy shortage caused by excessive pulling of glucose into glycogen and/or impaired capacity to degrade glycogen in the case of demand, interference with the unfolded protein response or with autophagy, or damage to the architecture of complex cells such as neurons might contribute to glycogen-induced neuronal cell death. Interestingly, a recent report proposes that a shortage in glucosyl units required for the production of NADPH through the pentose phosphate pathway leads to oxidative stress and cell death in neurons (Herrero-Mendez et al, 2009). Further research is required to identify the relevant molecular mechanisms linking excessive or aberrant glycogen accumulation to neuronal cell death.

The results presented here illustrate the need for a strict control of MGS activity in neurons under normal physiological conditions and raise the question as to why neurons have indeed maintained MGS expression throughout evolution. This paradox led Magistretti and Allaman (2007) to refer to MGS as the neuronal Trojan horse. The challenge now is to understand the biological significance of keeping MGS expressed but inactive in neuronal tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains and cDNAs

elav-Gal4, TH-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts and UAS-mCD8-GFP were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Centre. Transgenic flies expressing the wild-type and mutant forms of hMGS were generated as follows. hMGS-wt was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from a previously described clone (Cid et al, 2005) with the 5′ATGCCTTTAAACCGCACTTTG3′ and 5′TTAGTTACGCTCCTCGCCC3′ primers and cloned using the restriction endonucleases NotI/XbaI into pUAST. hMGS-9A and hMGS-9A(D) were amplified from previously described clones (Cid et al, 2005) with 5′ATGCCGCTGAACCGCAC3′ and 5′TTAGTTACGCTCCTCGCCC3′ primers and cloned using NotI/XbaI into pUAST. dGS was amplified using 5′ATGAATCGTCGCTTTTCGA3′ and 5′CTACTTAATCCCCAATTCCTT3′ primers from a cDNA library and cloned into pcDNA and subsequently excised using BglII/KpnI and inserted into pUAST. Fly strains carrying the corresponding transgenes were created by embryo injection of pUAST-hMGS-9A, pUAST-hMGS-9A(D), pUAST-hMGS-wt plasmids and pUAST-dGS.

Life span assay

For survival assays, flies were grown at 18°C and transferred to 29°C after hatching. Flies were reared at a maximum of 20 per tube and transferred every other day into fresh media and dead flies were counted. Flies were maintained on standard cornmeal/molasses/yeast/agar media with 60% humidity on a 12:12-h light–dark cycle. For each experiment two independent transgenic lines were used. For lifespan assays of transgenic fly lines, we performed all statistical analysis using Bioconductor (Gentleman et al, 2004). The logrank test was used to compare survival distributions between groups, as implemented in the survdiff function of the Bioconductor survival package. Using this software the logrank test returns a p-value of 0 when the calculated p is <1E-323.

Animal studies

All procedures were approved by the Barcelona Science Park's Animal Experimentation Committee and were carried out in accordance with the European Community Council Directive and National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Mice were allowed free access to a standard chow diet and water and maintained on a 12:12-h light–dark cycle under specific pathogen-free conditions in the Animal Research Centre at the Barcelona Science Park.

The paper explained

PROBLEM:

Brain glycogen is normally confined to astrocytes, where it serves as an energy reservoir for neurons. Nonetheless, large aggregates of glycogen are found in neurons under several pathological situations. One of the most striking cases is LD, a genetic form of progressive myoclonus epilepsy. However, the direct involvement of glycogen in the etiology of these pathologies remains controversial. Glycogen accumulation could be causative for, protective against, or even an innocuous accompanying event of neurodegeneration.

RESULTS:

We have generated fly and mouse transgenic models to address the consequences of forced glycogen production in neurons. Enhanced glycogen production in specific sets of neurons caused neurodegeneration and neurological disorders in both mice and flies. Mice accumulating glycogen in PCs suffered from ataxia while flies accumulating this polysaccharide in neurons had a reduced lifespan and locomotion defects.

IMPACT:

The demonstration that neuronal accumulation of glycogen production is harmful and contributes to disease pinpoints the enzymes involved in glycogen metabolism as potential targets for the treatment of LD and other neurodegenerative processes.

Generation of a conditional mMGS-9A transgenic mouse model

Targeting-vector construction and site-directed transgenic strategy were designed and performed by genOway (Lyon, France). Briefly, an expression cassette composed of the CAG promoter, a floxed STOP cassette and the mMGS-9A cDNA was introduced into the Hprt locus by homologous recombination in 129Ola (E14) embryonic stem (ES) cells. ES cell clones were then injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts and implanted into OF-1 pseudopregnant females. Highly chimeric males were selected for breeding with wild-type C57BL/6J females. Southern blot analyses were performed to confirm the presence of the recombined allele in females resulting from this breeding. Nestin-Cre and Pcp2-Cre animals were obtained from a commercial source (The Jackson Laboratory).

Genotyping

Genotyping was performed on DNA isolated from tail biopsy at the time of weaning. PCR primers for the Cre allele were Cre-f, 5′-GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC-3′ and Cre-r, 5′-GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3′. PCR primers for the mMGS-9A allele were MGS9A-f, 5′-CTGAGGCAGGAGAATCGCTTGAACC-3′ and MGS9A-r, 5′-AGCAAGAGAAGCAACGCCGTGG-3′.

Histology

Fly heads were cut and sunk into 10% formol and embedded in paraffin. Four-micrometer sections were rehydrated and used for PAS/haematoxylin staining. Images were taken with Nikon E600 with an Olympus DP72 camera. Image reconstruction was performed with ImageJ.

Mice were anesthetized with tiobarbital and perfused transcardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. They were then bisected sagittally and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded sections were prepared at 5 µm and used for H&E staining, PAS staining, Calbindin (1:100, Swant) and MGS (1:500, Epitomics) immunohistochemistry and TUNEL assay (Roche). Images were obtained with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope equipped with an Olympus DP72 camera.

Quantification of PC loss was performed on H&E stained sections. PCs were recognized as large cells with amphophilic cytoplasm, large nuclei with open chromatin and prominent nucleoli that were located in the Purkinje layer. Six fields per animal were analyzed. Counts were normalized to the length of the Purkinje layer, as measured by NIH ImageJ software and reported as PC survival (%). For the quantification of the TUNEL-positive PCs, two consecutive cerebellum slides were obtained; one was stained with H&E and the other was used for the TUNEL assay. TUNEL-positive PCs and total PCs were counted in six corresponding fields per animal. Results are reported as percentage of TUNEL-positive PC.

Electron microscopy

Fly heads were dissected in fixative and further fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaldehyde in 0.12 M phosphate buffer (PB). Heads were washed in PB and transferred to 2% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated and embedded in epoxy resin. Fifty-nm ultrathin sections were collected on formvar-coated slot grids and stained with lead citrate. Images were taken using a Tecnai Spirit transmission electron microscope.

Behavioural analysis

Fly climbing

Fifteen to 20 flies per assay were placed in a clean tube 24 h before the experiment. Tubes were tapped and recorded. The trajectory of flies in the tube was traced as a segmented line. Kymograph was used to calculate the speed of each moving object. The slope of each trajectory in the tube was calculated manually using the end point coordinates, multiplied by the length of the tube (in mm) and divided by the speed of the movie (30 frames/s) to obtain an individual speed in mm/s. All procedures were performed on ImageJ. An average speed per genotype per time point was obtained from at least two different crosses. Average speeds were compared using unpaired t-test.

Mouse phenotype analysis

mMGS-9APcp2 mice and littermate controls were evaluated on the footprint assay, walking beam test and rotarod test at several ages. For the gait analysis on the footprint assay, the paws of the mice were dipped in non-toxic water-soluble paints. The animals were allowed to walk on replaceable strips of paper. The walking beam consisted of a 13-mm wide 1-m long round beam suspended at 50 cm. Mice were trained to cross the beam quickly and without stopping. Each mouse was tested three times on the walking beam. The data reported are the time to cross the beam and the number of hind limb slips. For rotarod analysis, EMPRESS SOP was followed (http://empress.har.mrc.ac.uk, doc. number: 10_009). Briefly, mice were trained for 1 min on a rod rotating at 4 rpm. The rod was then set to accelerate from 4 to 40 rpm in 300 s. Three test trials were performed for each animal, leaving a 15-min interval between the start of consecutive trials. The data reported for each mouse are the average latency to fall from the rod for the three trials. Clinging to the rod for a full rotation was scored as a fall.

All behavioural tests were performed in the latter half of the light phase of a 12-h light–dark cycle.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined by Student's t-test using GraphPad Prism software (version 5; GraphPad Software, Inc.).

For more detailed Materials and Methods see the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Bloomington Stock Centre for flies and reagents. We also thank N. Plana (IRB Barcelona), A. Serafín and X. Cañas (Barcelona Science Park) for their technical assistance. Thanks also go to C. López (University of Barcelona Electron Microscopy Unit), E. Planet (IRB Barcelona Biostatistics/Bioinformatics Unit), J. Colombelli (IRB Microscopy Facility) and A. Olza (IRB Barcelona Drosophila Injection Service). We also acknowledge J. Avila (Centro de Biología Molecular, Spain) and D. Vilchez (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies, USA) for comments on the manuscript and T. Yates (IRB Barcelona) for help in its preparation. MM is an ICREA Research Professor and MM's laboratory was funded by grants from the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (BFU2010-21123 and CSD2007-00008), the Generalitat de Catalunya (2005 SGR 00118) and the EMBO Young Investigator Programme. JJG's laboratory was funded by grants from the Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica (BFU2008-00769), the Generalitat de Catalunya (2009 SGR 01176), the Fundación Marcelino Botín and the CIBER de Diabetes y Enfermedades Metabólicas Asociadas (ISCIII, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación). This research was also supported by a Marie Curie Intra European Fellowship within the 7FP to JC and by an IRB Barcelona Interdisciplinary fellowship to MFT.

Supporting Information is available at EMBO Molecular Medicine online.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

JJG and MM designed the overall study. JD and MFT designed and performed the research corresponding to the mouse and fly models, respectively. MGR generated data and participated in the preparation of the revised version of the manuscript. JD, MFT, JC, MM and JJG analyzed the data, and participated in writing the article, and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

For more information

OMIM Lafora disease: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/254780

Human disease to Drosophila gene database: http://superfly.ucsd.edu/homophila/

Supplementaary material

Detailed facts of importance to specialist readers are published as ”Supporting Information”. Such documents are peer-reviewed, but not copy-edited or typeset. They are made available as submitted by the authors.

References

- Aguado C, Sarkar S, Korolchuk VI, Criado O, Vernia S, Boya P, Sanz P, de Cordoba SR, Knecht E, Rubinsztein DC. Laforin, the most common protein mutated in Lafora disease, regulates autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:2867–2876. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barski JJ, Dethleffsen K, Meyer M. Cre recombinase expression in cerebellar Purkinje cells. Genesis. 2000;28:93–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestetti G, Rossi GL. Hypothalamic lesions in rats with long-term streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. A semiquantitative light- and electron-microscopic study. Acta Neuropathol. 1980;52:119–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00688009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouskila M, Hirshman MF, Jensen J, Goodyear LJ, Sakamoto K. Insulin promotes glycogen synthesis in the absence of GSK3 phosphorylation in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294:E28–E35. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00481.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouskila M, Hunter RW, Ibrahim AF, Delattre L, Peggie M, van Diepen JA, Voshol PJ, Jensen J, Sakamoto K. Allosteric regulation of glycogen synthase controls glycogen synthesis in muscle. Cell Metab. 2010;12:456–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM. Brain glycogen re-awakened. J Neurochem. 2004;89:537–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, Ransom BR. Astrocyte glycogen and brain energy metabolism. Glia. 2007;55:1263–1271. doi: 10.1002/glia.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo AM, Broadwell RD. Cytochemical identification of cerebral glycogen and glucose-6-phosphatase activity under normal and experimental conditions. II. Choroid plexus and ependymal epithelia, endothelia and pericytes. J Neurocytol. 1986;15:511–524. doi: 10.1007/BF01611733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid E, Gomis RR, Geremia RA, Guinovart JJ, Ferrer JC. Identification of two essential glutamic acid residues in glycogen synthase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33614–33621. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005358200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cid E, Cifuentes D, Baque S, Ferrer JC, Guinovart JJ. Determinants of the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of muscle glycogen synthase. FEBS J. 2005;272:3197–3213. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criado O, Aguado C, Gayarre J, Duran-Trio L, Garcia-Cabrero AM, Vernia S, San Millan B, Heredia M, Roma-Mateo C, Heredia M, et al. Lafora bodies and neurological defects in malin-deficient mice correlate with impaired autophagy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;21:1521-1533. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DA, Brand AH. The GAL4 system: a versatile system for the expression of genes. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;420:79–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-583-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh S, Agarwala KL, Ueda K, Akagi T, Shoda K, Usui T, Hashikawa T, Osada H, Delgado-Escueta AV, Yamakawa K. Laforin, defective in the progressive myoclonus epilepsy of Lafora type, is a dual-specificity phosphatase associated with polyribosomes. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2251–2261. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.hmg.a018916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh S, Delgado-Escueta AV, Sakamoto T, Avila MR, Machado-Salas J, Hoshii Y, Akagi T, Gomi H, Suzuki T, Amano K, et al. Targeted disruption of the Epm2a gene causes formation of Lafora inclusion bodies, neurodegeneration, ataxia, myoclonus epilepsy and impaired behavioral response in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1251–1262. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.11.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry MS, Worby CA, Dixon JE. Insights into Lafora disease: malin is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates and promotes the degradation of laforin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8501–8506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503285102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertz HJ, Cervos-Navarro J, Frydl V, Schultz F. Glycogen accumulation of the aging human brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 1985;31:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(85)90024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero-Mendez A, Almeida A, Fernandez E, Maestre C, Moncada S, Bolanos JP. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:747–752. doi: 10.1038/ncb1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ianzano L, Zhang J, Chan EM, Zhao XC, Lohi H, Scherer SW, Minassian BA. Lafora progressive myoclonus epilepsy mutation database-EPM2A and NHLRC1 (EPM2B) genes. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:397. doi: 10.1002/humu.9376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim MZ. The response of the brain to hypoxia and ischaemia. J Neurol Sci. 1972;17:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(72)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow HR, Lesikar DD, Antwi D, Tan AW. L-type glycogen synthase. Tissue distribution and electrophoretic mobility. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:9953–9956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi J, Shiraishi H, Minei S. Ultrastructural appearance of glycogen in neuron and astrocyte of the human cerebral cortex adjacent to brain tumors. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 1970;19:355–359. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leel-Ossy L. The occurrence of corpus amylaceum (polyglucosan body) in diabetes mellitus. Neuropathology. 1995;15:108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Long DM, Mossakowski MJ, Klatzo I. Glycogen accumulation in spinal cord motor neurons due to partial ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 1972;20:335–347. doi: 10.1007/BF00691750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti PJ, Allaman I. Glycogen: a Trojan horse for neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1341–1342. doi: 10.1038/nn1107-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire SE, Mao Z, Davis RL. Spatiotemporal gene expression targeting with the TARGET and gene-switch systems in Drosophila. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:pl6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2202004pl6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Peterson RG, Felten DL, O'Connor BL. Glycogen accumulation in tibial nerves of experimentally diabetic and aging control rats. J Neurol Sci. 1981;52:289–303. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(81)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell H, Knox D, Lee S, Charters AC, Orloff M, Garrett R, Lampert P. Alloxan diabetic neuropathy: electron microscopic studies. Neurology. 1977;27:60–66. doi: 10.1212/wnl.27.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri R, Ganesh S. Laforin in autophagy: a possible link between carbohydrate and protein in Lafora disease. Autophagy. 2010;6:1229–1231. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach PJ, Cheng C, Huang D, Lin A, Mu J, Skurat AV, Wilson W, Zhai L. Novel aspects of the regulation of glycogen storage. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;9:139–151. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.1998.9.2-4.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, Llinas R, Greengard P. Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1553–1558. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay SS, Wong WC. Ultrastructural changes in the gracile nucleus of the spontaneously diabetic BB rat. Histol Histopathol. 1991;6:43–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schutz G. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull J, DePaoli-Roach AA, Zhao X, Cortez MA, Pencea N, Tiberia E, Piliguian M, Roach PJ, Wang P, Ackerley CA, et al. PTG depletion removes Lafora bodies and rescues the fatal epilepsy of Lafora disease. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valles-Ortega J, Duran J, Garcia-Rocha M, Bosch C, Saez I, Pujadas L, Serafin A, Canas X, Soriano E, Delgado-Garcia JM, et al. Neurodegeneration and functional impairments associated with glycogen synthase accumulation in a mouse model of Lafora disease. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:667–681. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernia S, Rubio T, Heredia M, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Sanz P. Increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and decreased proteasomal function in Lafora disease models lacking the phosphatase laforin. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilchez D, Ros S, Cifuentes D, Pujadas L, Valles J, Garcia-Fojeda B, Criado-Garcia O, Fernandez-Sanchez E, Medrano-Fernandez I, Dominguez J, et al. Mechanism suppressing glycogen synthesis in neurons and its demise in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/nn1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wender R, Brown AM, Fern R, Swanson RA, Farrell K, Ransom BR. Astrocytic glycogen influences axon function and survival during glucose deprivation in central white matter. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6804–6810. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06804.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.