Abstract

Background

Lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender (LBQT) women living with HIV have been described as invisible and understudied. Yet, social and structural contexts of violence and discrimination exacerbate the risk of HIV infection among LBQT women. The study objective was to explore challenges in daily life and experiences of accessing HIV services among HIV-positive LBQT women in Toronto, Canada.

Methods

We used a community-based qualitative approach guided by an intersectional theoretical framework. We conducted two focus groups; one focus group was conducted with HIV-positive lesbian, bisexual and queer women (n=7) and the second with HIV-positive transgender women (n=16). Participants were recruited using purposive sampling. Focus groups were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis was used for analyzing data to enhance understanding of factors that influence the wellbeing of HIV-positive LBQT women.

Results

Participant narratives revealed a trajectory of marginalization. Structural factors such as social exclusion and violence elevated the risk for HIV infection; this risk was exacerbated by inadequate HIV prevention information. Participants described multiple barriers to HIV care and support, including pervasive HIV-related stigma, heteronormative assumptions in HIV-positive women's services and discriminatory and incompetent treatment by health professionals. Underrepresentation of LBQT women in HIV research further contributed to marginalization and exclusion. Participants expressed a willingness to participate in HIV research that would be translated into action.

Conclusions

Structural factors elevate HIV risk among LBQT women, limit access to HIV prevention and present barriers to HIV care and support. This study's conceptualization of a trajectory of marginalization enriches the discussion of structural factors implicated in the wellbeing of LBQT women and highlights the necessity of addressing LBQT women's needs in HIV prevention, care and research. Interventions that address intersecting forms of marginalization (e.g. sexual stigma, transphobia, HIV-related stigma) in community and social norms, HIV programming and research are required to promote health equity among LBQT women.

Keywords: lesbian, bisexual, transgender, women, HIV seropositivity, stigma, discrimination, qualitative, Canada

Background

Lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender (LBQT) women living with HIV have been described as invisible, ignored, neglected and understudied [1–4]. Lesbian, bisexual and queer (LBQ) women were considered at risk at the beginning of the epidemic and were almost prohibited from donating blood; this perception was a shift from the mid-1980s when LBQ women were constructed as “immune” to HIV and not relevant to HIV research and practice [2,5]. As a result, the gender focus in HIV research, prevention, treatment and care predominately examines cisgender, heterosexual women [2,4,6,7].

Although LBQ women are often perceived as low risk for HIV infection, many factors may contribute to LBQ women's HIV transmission risks: sex with men, sex work, injection drug use and/or sexual violence [4,8–10]. These individual and social level risk factors may be contextualized within structural drivers of HIV acquisition and transmission, such as social, political and economic factors contributing to social inequities [11,12]. For instance, a large evidence base shows associations between stigma and discrimination targeting sexual minorities and increased substance use [13,14]; studies report higher HIV incidence among women injection drug users (IDU) who have sex with women in comparison with other women IDU, in part due to social isolation, poverty, higher risk injection practices and sexual risk behaviour [15–17]. The term WSW, women having sex with women, was developed to challenge fixed and categorical conceptualizations of sexuality, and LBQ/WSW researchers underscore the importance of understanding that sexual identity, behaviour and desire do not always align and women who identify as LBQ/WSW may have histories of engaging in consensual and non-consensual sex with men for complex reasons [2,3,5,8,14,18–20]. This complexity of women's sexuality is not well understood or integrated in HIV services; a qualitative study with HIV-positive WSW in the United States revealed a lack of resources tailored for HIV-positive WSW [1]. Researchers have described a low level of engagement of HIV-positive LBQ women in HIV treatment and care [9,21,22]. These findings call for more attention to the experiences of HIV-positive LBQ women accessing treatment, care and support.

Transgender women have been described as having elevated risk for HIV infection. A meta-analysis of US-based studies synthesized weighted means across 29 studies to estimate HIV prevalence rates and reported that rates among transgender women ranged from 11.8% (self-report) to 27.7% (HIV test results) [23]. Transgender women's exacerbated vulnerability to HIV infection has been attributed to social and structural contexts of widespread violence and discrimination in housing, employment, educational and healthcare systems [24–26]. Transgender women's involvement in sex work in the United States has been associated with lower levels of education, homelessness, substance use and reduced social support [27]; inconsistent condom use among transgender sex workers has been linked with low self-esteem, a history of forced sex and substance use [28]. A systematic review indicated that transgender female sex workers had significantly higher risks for HIV infection in comparison with transgender women not involved in sex work, male sex workers and cissexual female sex workers [29]. The limited research that has been conducted with HIV-positive transgender people in the United States suggests that healthcare providers may not have the knowledge, training and skills to adequately serve HIV-positive transgender people [26,27,30]. Qualitative research in Canada highlighted barriers to competent healthcare among transgender people and recommended additional research to explore the experiences of HIV-positive transgender people [31].

The convergence of HIV-related stigma, sexual stigma, homophobia, heterosexism, transphobia and cisnormativity may account for the lack of research focus on HIV-positive LBQT women [2,3,31]. HIV-related stigma refers to the devaluing of, and discrimination towards, people who are HIV-positive or associated with HIV [32]. Sexual stigma refers to the devaluing of sexual minorities and the negative attitudes and lower levels of power afforded to non-heterosexual behaviours, identities, relationships and communities [33]. Homophobia refers to discrimination, fear, hostility and violence towards sexual minorities [34,35]. Heterosexism is a socio-cultural power structure that reinforces sexual stigma and refers to the normalization of heterosexuality and the subsequent devaluation and invisibility of non-heterosexual sexualities [35]. Cisgender refers to non-transgender people and cissexual to people who experience alignment between gender identity and physical sex [36]. Transphobia refers to fear and hatred of transgender people; the term cisnormativity was developed to describe the socio-cultural assumptions and expectations that all people are cissexual and may better capture the systemic nature of transgender people's marginalization than transphobia [31].

This study utilized a theoretical approach grounded in intersectionality to understand how these multiple forms of stigma (HIV-related stigma, sexual stigma, homophobia, heterosexism, transphobia, cisnormativity) influence access to HIV services among LBQT women. Intersectionality highlights the interdependent and mutually constitutive relationship between social identities and social inequities [37–39], particularly relevant in the context of HIV-related stigma that exacerbates social and structural inequities based on race, class, gender and sexual orientation [40]. Intersectional stigma encompasses interlocking forms of stigma across micro (individual), meso (social) and macro (institutional) domains [41]. Little is known about the links between intersectional stigma and experiences of HIV-positive LBQT women accessing the spectrum of HIV services, including prevention, treatment, care and support [2,3,31]. The purpose of this study was to explore challenges and experiences accessing HIV services among HIV-positive LBQT women to strengthen the development of appropriate HIV support and secondary HIV prevention programmes. Analytic questions that guided this study included:

What challenges did participants experience in daily life?

What were participants’ experiences accessing HIV prevention, care and support services?

Methods

Study design

This qualitative investigation was conducted in partnership between a women's community health centre (CHC) and a women's health research institute in Toronto, Canada. A community advisory board (CAB) (n=11) comprising members from agencies providing health/social services to HIV-positive women was developed to provide consultation on research design and data interpretation. The CAB included one HIV-positive LBQ woman and one HIV-negative transgender woman. The data came from a larger study of 15 focus groups conducted with HIV-positive women (n=104) across Ontario, Canada, where we developed the conceptual model of “intersectional stigma” [41]. The present study exclusively examined the responses from two focus groups conducted in Toronto (one with LBQ women; one with transgender women) to better understand the associations between intersectional stigma and HIV prevention, treatment, care and support among HIV-positive LBQT women. Scant research has addressed the unique needs of HIV-positive LBQT women, and the sheer number of populations and focus groups in the larger study prohibited us from conducting a rich, in-depth analysis of this data. We also extend beyond the larger study's focus on homophobia and transphobia to employ analyses of heterosexism and cisnormativity.

Focus groups facilitate understanding people's interpretation of experiences, promote community involvement in research, highlight diverse population's experiences of service provision, and allow for in-depth probing of experiences, feelings and opinions [42–44]. As the inclusion of a range of populations and locations in the larger study had budgetary and time constraints, focus groups were more feasible and cost-efficient to conduct than individual in-depth interviews. Limitations of focus groups include, ensuring all participants feel comfortable speaking, managing dominant voices, the trend towards reproducing normative discourses and differences in abilities of participants to articulate thoughts and experiences [42–44].

Participants were recruited in 2009 to 2010 using purposive and convenience sampling [45,46]. Specifically, participants were recruited via word-of-mouth and flyers in community agencies, including AIDS service organizations (ASO), HIV support programmes, LBQT centres and CHCs. Peer research assistants (PRA) were hired and trained to assist with participant recruitment and focus group co-facilitation. Each focus group was conducted at a women's CHC located in downtown Toronto. Focus groups were co-facilitated by a PRA and a research coordinator (CL) who was a doctoral candidate trained in conducting focus groups. PRA were provided with one-day training in research methods and ethics. All participants provided informed consent. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at Women's College Hospital in Toronto.

We used a semi-structured focus group interview guide to explore, (1) personal, social and heathcare challenges and experiences; (2) issues silenced in one's communities; (3) engagement in, and knowledge of, HIV research. Questions included, (1) “What challenges do lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender women living with HIV in Ontario face?”, (2) “What HIV research are you aware of that addresses these challenges?”, (3) “What issues do you feel people in your communities (e.g. sexual orientation/gender identity, religion, culture) are silent about? (e.g. stigma, taboo, off limits)”, (4) “What would motivate you to participate in any HIV research?”.

Data analysis

Focus groups were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, entered into NVivo 8 qualitative analysis software and examined with thematic analysis. Thematic analysis, a method used to identify, analyze and report themes in data, can be applied across diverse theoretical approaches and integrates inductive and deductive analyses [37]. Inductive analyses were used to identify new themes that evolved in the data (e.g. heteronormative assumptions in women's support groups), and deductive approaches were used to explore themes identified by the intersectional theoretical approach guiding the study (e.g. sexual stigma).

Two investigators (CL and LJ) conducted thematic analyses by reading the transcripts several times and noting preliminary ideas, producing initial codes by highlighting relevant data (e.g. experiences of rejection), generating themes by collating codes across the data set (e.g. social exclusion), reviewing themes to develop a thematic map (e.g. trajectory of marginalization), refining themes (e.g. structural risk factors) and generating the final report by selecting examples of themes and relating findings to the literature [47]. No major new themes emerged after coding the two focus groups, indicating saturation was attained. Member checking was conducted to verify findings at meetings with PRA and the CAB, who were in agreement with the current analysis [42].

Results

Participant characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics of focus group participants (n=23) are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants in each focus group earned an annual income below US$20,000, indicating lower socio-economic status. While an attempt was made to recruit 10 to 12 participants per group, the LBQ group was undersubscribed (n=7) and the transgender group was oversubscribed (n=16). This discrepancy could be reflective of the dearth of services for HIV-positive LBQ women in contrast with a transgender women's drop-in programme in close proximity to the focus group location.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of focus group participants (n=23).

| Characteristic | Lesbian, bisexual and queer group (n=7) | Transgender group (n=16) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | |||

| Age, years | ||||

| Range | 27 to 45 | 7 | 25 to 57 | 15 |

| Mean | 34.0 (SD 7.6) % | 7 | 37.5 (SD 9.3) | 15 |

| Annual income | 6 | 14 | ||

| 0 to $19,999.00 | 66.7 | 4 | 71.4 | 10 |

| $20,000 to $39,999.00 | 16.7 | 1 | 21.4 | 3 |

| >$40,000.00 | 16.7 | 1 | 7.1 | 1 |

| Highest level of education | 6 | 13 | ||

| Some high school or less | 33.3 | 2 | 38.5 | 5 |

| High school | – | – | 15.4 | 2 |

| Some college/university | – | – | 7.7 | 1 |

| Completed college/university | 66.7 | 4 | 38.5 | 5 |

| Sexual orientation | 7 | 14 | ||

| Heterosexual | – | – | 71.4 | 10 |

| Bisexual | 57.1 | 4 | 14.3 | 2 |

| Queer | 28.6 | 2 | 14.3 | 2 |

| Lesbian | 14.3 | 1 | – | – |

| Region of birth | 7 | 15 | ||

| North America | – | – | 53.3 | 8 |

| Africa | 85.7 | 6 | – | – |

| Caribbean | 14.3 | 1 | 20.0 | 3 |

| Central America | – | – | 13.3 | 2 |

| Europe | – | – | 13.3 | 2 |

| Years living in Canada | ||||

| Range | 0.7 to 2.8 | 7 | 8.0 to 57.0 | 13 |

| Mean | 1.7 (SD 1.0) | 7 | 26.7 (SD 13.2) | 13 |

| Ethnicity | 7 | 15 | ||

| African | 85.7 | 6 | 6.7 | 1 |

| Caribbean | 14.3 | 1 | 26.7 | 4 |

| European | – | – | 20.0 | 3 |

| Aboriginal | – | – | 20.0 | 3 |

| “Canadian” | – | – | 13.3 | 2 |

| Latina | – | – | 13.3 | 2 |

Findings highlight experiences of marginalization across multiple domains such as structural risk factors; gaps in HIV prevention; barriers to HIV treatment, care and support; and underrepresentation in HIV research. Table 2 provides illustrative examples of themes and sub-themes discussed in the focus groups.

Table 2.

Overview of lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender focus group participants’ (n=23) descriptions of marginalization

| Themes | Sub-themes | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Structural risk factors | Social exclusion | “You have to pretend to love men” (Lesbian, bisexual queer – LBQ participant 6). “I knew I was gay all my life, but I couldn't talk to my mother about it, and I couldn't talk to anyone in my whole school. I had to keep it to myself, and it was very difficult. You're asking the question ‘Why am I here? Am I the only person here?’” (LBQ participant 1). “We need more visibility. The community is silent about the transgenders, most of the time you hear about gay men, lesbian” (Transgender participant 16). |

| Violence | “Either we are tortured or threatened to be killed” (LBQ participant 2). “I used to volunteer but I had to stop because it's targeted as a gay community. So they will target you when you are going into the building at a certain time” (Transgender participant 8). | |

| Inadequate HIV prevention | Insufficient HIV prevention information | “There is no information. Talk about the way a lesbian can and cannot get HIV—prevention” (LBQ participant 2). “Sometimes you're accidentally online and doing stuff and you find out the [HIV prevention] information that way. But it's basically word of mouth” (Transgender participant 12). |

| Gaps in secondary HIV prevention | “It's not everyone that you can tell about your sexual orientation. Sometimes you are dealing with the fact that okay, I'm HIV-positive, and this is an HIV-positive organization. Then you are adding another thing, maybe I'm risking too much. So where do I go when I'm queer? You start to hold back and in that period you are missing out. You don't access information” (LBQ participant 2). “I don't even think my doctor would know [about secondary HIV prevention] unless I told him. And the only way I'm going to be able to tell him is if you guys [other participants] tell me” (Transgender participant 9). | |

| Barriers to HIV care and support | Heternormative assumptions | “You have your own extra button. Like, okay, I'm HIV positive like you are, but I have something else, I'm bisexual. So you are not accommodated in those organizations” (LBQ participant 4). “You feel out of place, and you're supposed to be in this women's group, and they are talking about their sexuality. Yesterday it came out again, some apologies about lesbian and gays very sarcastically” (LBQ participant 6). |

| HIV-related stigma | “High stigma. That's the major challenge—most of us are not willing to come out [as HIV-positive]” (LBQ participant 2). “People get so confused, they want to talk to other people about it [HIV] but they're told not to and they're afraid” (Transgender participant 6). | |

| Discriminatory and incompetent healthcare | “You can tell the way they say it [your name] – you're not a normal person. There is a pause and then they look you in the eye” (Transgender participant 15). “As soon as they know you're transgender they should automatically refer to you as she. When you stand in front of them and you look like a woman, don't call me Mr.” (Transgender participant 2). | |

| Underrepresentation in HIV research | Constrained visibility in HIV discourse | “I haven't read any research focused on the queer woman living with HIV” (LBQ participant 1).“We lack research” (Transgender participant 11). |

| Need for knowledge-to-action | “I would like to see the results implemented to the benefit of the lesbian and bisexual communities and other women” (LBQ participant 1) “A big piece of research could be directed at actual researchers and at doctors and agencies to train them” (Transgender participant 3) |

Structural risk factors

Participants discussed social exclusion and violence rooted in homo/transphobia as environmental factors that silenced discussion of non-heterosexual sexualities and exacerbated HIV infection risks. Social exclusion and violence are examples of structural factors that enhance vulnerability to HIV [48].

Social exclusion

Social exclusion was discussed by both focus groups—LBQ women elaborated on social exclusion from friends and family, whereas transgender women discussed exclusion from cisgender lesbian, gay and bisexual communities. Social exclusion often resulted in LBQ women hiding their sexual orientation from family and friends to avoid ostracism or other negative consequences. In response to a question about challenges experienced in daily life, a participant described, “It's either we are tortured or threatened to be killed. It's just a lot of things that you go through whenever you're out in the open and say, ‘I'm lesbian or bisexual’, they don't accept you as a human being” (LBQ participant 2). Hiding often meant having a boyfriend to “cover up” their same-sex sexuality. As another participant explained:

You need to hide. If ever your parents ask you “who are you dating”, obviously you need to point a man, not a woman. You need to be “I'm dating Bruce, I'm dating Sam”. So that it can cover you up, so that they can't do something bad on you, or disown you or something. So, in that way you are forced to be living a double life, like bi[sexual]. Even if you know very well that I'm only attracted to women, you learn to be with men, so that you can be in the same community as any other person. (LBQ participant 1)

Other participants reported actively concealing their sexual orientation, “you need to get down there and hide yourself” (LBQ participant 4). Hiding resulted in feeling silenced and living in disguise, “we have been operating in silence, and putting a mask, pretending that we are just like everyone else” (LBQ participant 3).

Hiding also left limited space for discussion of same-sex sexuality, “normally we don't even want to hear what a straight couple do, but then a person who is straight can speak freely and talk about just about anything. But, you, as a person who is queer, you can't” (LBQ participant 7). This silence around same-sexuality was actively reinforced, participant accounts indicate they were dissuaded from discussing intimate parts of their lives, “A lot of time most people don't really want to hear about your sexuality. You're just shushed, brushed off. ‘I don't want to hear what you do’. So, it would be good if there is someone to listen to you, like when you're talking rather than to shush” (LBQ participant 2). As a consequence, there was little validation of their existence as sexual minority women, “we don't exist” (LBQ participant 7).

Transgender participants discussed social exclusion within cisgender gay, LBQ communities. A participant articulated, “I think a lot of things have to be changed, especially in the gay community. They look for the gay men first and lesbians. We have no structure. We still have nothing” (Transgender participant 8). Notably, almost one-third of transgender participants did not identify as heterosexual (Table 1). Therefore, this lack of support from sexual minority communities was particularly painful for transgender participants who described pervasive discrimination in society at large:

They always have something bad to say about transgenders: ‘Oh they should stay one way. God didn't make them so whatever’. When there's a transgender jobs are so hard to get and that's why they have to go to the sex trade and work. And there's just so much things—you have to change your name and change this and change that. It's hard to go and do all these things. That is very silent in the gay community. (Transgender participant 11)

This lack of support for transgender people led a participant to declare, “the gay people have prestige. We're just left by the wayside. Queens end up low class. If you're more flamboyant, you want to be more real woman than them. They'll look and they'll say ‘oh my God, look at this faggot’” (Transgender participant 13). This highlights both perceived class differences as well as intersections of transphobia with “flamboyance”, suggesting gender non-conformity stigma is experienced both within and outside of cisgender gay, LBQ communities.

Violence

Both LBQ and transgender participants discussed being targeted by homo/transphobic violence. An LBQ participant (3) reported, “I got my HIV through my brothers, they gang raped me” [31]. A transgender woman (9) explained, “I've always been flamboyant. So, I've always been targeted. In 2004 I had a brutal attack. I was actually left for dead. I was gang banged on my way home from work. I was stabbed and all. I was saved by Grace”. This violence was attributed to social norms that stigmatize sexual minorities, “They see you being queer as being demonic or it is evil. So, they will do things to you, torture” (LBQ participant 6) [41].

Inadequate HIV prevention

Lesbian, bisexual and queer and transgender women discussed difficulty accessing appropriate HIV prevention information. There was also a dearth of information regarding secondary HIV prevention tailored for HIV-positive LBQ women.

Insufficient HIV prevention information

When it came to HIV prevention, a participant articulated, “women who are queer are mostly forgotten, I can say that” (LBQ participant 4). This lack of attention promulgated the notion that LBQ women were risk free, “people think ‘I'm lesbian, I cannot get HIV’” (LBQ participant 1). Another participant's narrative highlights the exclusion of LBQ women from HIV prevention programmes:

You are supposed to get that information in the HIV [prevention] course, right? They only focus on heterosexual people. They only talk about condoms and stuff. And as much as we know there are dental dams, they don't talk about it. So, you don't even know what else is out there that's dangerous for you as a queer woman, because all you know is heterosexual that exists in this world, and the gay man communities out there (LBQ participant 5) [41].

Transgender participants also described feeling left out of HIV prevention programmes and highlighted the need for tailored information. A participant articulated, “they don't do enough output about what exactly they do. They do outreach and stuff with condoms for sex trade workers and they're focused more on gay men” (Transgender participant 7).

Gaps in secondary HIV prevention

Lesbian, bisexual and queer participants described not knowing how to protect female partners from HIV infection. A participant expressed, “they have MSM [men who have sex with men] prevention. So, what about us queer women who are positive, where do we go?” (LBQ participant 3). Another participant corroborated this sentiment, “They [AIDS organizations] so much cater for the men, I don't know what can be done to look at women. As much as we can go to them, it's not really our space” (LBQ participant 7).

Yet, when ASO did focus on women, LBQT women were still excluded. A participant detailed her experience attempting to acquire secondary HIV prevention information at an HIV-positive women's meeting:

You are just left out. The information is not much for you to get. And it's very, very difficult to ask. I remember one day we were in a meeting and I was asking, “Okay, I want to know who to talk to because I am bisexual”. And people went, “Oh!” – like I said something that's strictly out of this world. But I meant it – I do have problems which I need to talk to someone who can give me services, who can give me direction, who can tell me what to do when this happens. It's like you just said something that's not human. So, sometimes you don't even partake because whatever they are saying is hetero. (LBQ participant 4)

Women also discussed wanting support for other important sexual reproductive health issues such as starting a family, “if you're queer you should be able to go and have someone who will discuss that with you, as a woman who is HIV positive, queer, and wants to start a family” (LBQ participant 6).

Transgender participants described difficulty in negotiating secondary HIV prevention with both boyfriends and paid sex partners. As one woman explained, “I think a lot of it is like acceptance, accepting yourself. I mean a lot of my boyfriends have been HIV [positive]. It's hard to have sex. It's hard to have a family, a normal life. I think it's bad and HIV is mainly focused on the sex industry. I'm saying it's hard” (Transgender participant 5). This narrative highlights how low self-acceptance may inhibit positive sexual experiences among HIV-positive transgender women.

Another participant described the difficulty in negotiating safer sex as an HIV-positive transgender sex worker, “I got a deportation order from Canada. I'm HIV [positive]. Would you sell a customer [sex] if you have HIV? Like, I'm going to tell a customer ‘oh I have HIV’. Basically it tells me that an HIV person cannot have sex any more. You know what, I wish I could talk that openly but I don't know. I'm not prepared to do it” (Transgender participant 7). This narrative highlights both the need for information regarding discussing safer sex among transgender sex workers and the immense consequences – such as deportation because of criminalization of HIV transmission – for people who do not feel equipped to have that conversation.

In response to a question as to where HIV-positive transgender women receive secondary HIV prevention information, participants highlighted the lack of information and subsequent reliance on word-of-mouth. One participant responded, “They can go to community drop in places, word-of-mouth I guess” (Transgender participant 4). Another participant agreed, “I think word-of-mouth more than anything. Walk-in clinics, they do a lot but I don't think they do enough” (Transgender participant 10). A third participant concurred, “Sometimes it's word of mouth or you're accidentally online and doing stuff and you find out the information that way. But as a sex trade worker, it's basically word-of-mouth” (Transgender participant 14). The lack of information, coupled with difficulties negotiating safer sex, presented significant barriers for secondary HIV prevention among transgender participants.

Barriers to HIV care and support

Heteronormative assumptions in support groups, HIV-related stigma and discriminatory/incompetent healthcare were discussed as barriers to accessing appropriate HIV care and support.

Heteronormative assumptions in support groups

Participant narratives reflect a lack of recognition that HIV-positive LBQ women exist, “right now you just get stuck either being an HIV-positive woman or being queer, but not at the same time” (LBQ participant 3). Heteronormative assumptions were particularly pronounced in HIV-positive women's support groups, “it's almost completely straight women and people just assume you're straight” (LBQ participant 2). Such assumptions resulted in participants feeling silenced, “when you come for a group, they are talking about their sexuality, boyfriends. You can't speak” (LBQ participant 5).

This silence was reinforced by a lack of support when LBQ issues were broached. A participant recounted an unsupportive reaction when she suggested an HIV-positive women's programme participate in gay pride events, “she [the manager] said: ‘we're not interested in that’. Pride is just something that's just taboo. You can't even talk about it” (LBQ participant 1). As a result, participants felt that HIV-positive women's programmes were not a safe space for LBQ women, “as much as you want to go to this group, you want to identify yourself with the HIV-positive groups, at times you feel like you don't belong there” (LBQ participant 7). Another participant articulated, “You can't really be who you are” (LBQ participant 2).

HIV-related stigma

Both LBQ and transgender focus groups named pervasive HIV-related stigma as a barrier to accessing care and support. As a LBQ participant (5) explained:

The high stigma attached to AIDS, even from our own community, to even the HIV/AIDS movement, it is still attacked. We are apprehensive about coming out [as HIV-positive]. We also hear about how the society is talking about it [HIV]. It's really a very big challenge.

A transgender participant (14) described enacted HIV-related stigma, “people with HIV are so judged and ridiculed”.

HIV-related stigma may intersect with other identities. For example, several participants described HIV-related stigma was more pronounced in certain communities. An Aboriginal transgender participant (4) noted, “transgenders with HIV, especially across Canada in the Native community, a lot of them are told to be quiet about their [HIV] status”. Another transgender participant's (9) narrative highlights HIV-related stigma as an obstacle to participating in HIV services:

For me the big barrier is to participate. I feel afraid to be recognized, especially in the ethnic community. When they recognize people with HIV [pause] … today I decided to come, there are no Spanish people here.

Transgender participants also highlighted that an HIV-positive diagnosis often meant that people perceived them as gay men – rather than as a transgender women. The belief that HIV is a “gay disease”, coupled with ignorance regarding transgender identity, meant that transgender people's HIV-positive serostatus overpowered self-defined gender identity. As a transgender participant (2) described, “HIV—it's automatically a gay thing. That even makes it harder for people. You go to your boss and you say ‘I'm HIV [positive]’. And the boss automatically thinks: ‘Okay, you slept with a man. You're a man’”.

Discriminatory and incompetent healthcare

Transgender participants described widespread, pervasive, discriminatory and incompetent care from healthcare professionals. Several participants believed healthcare professionals lacked education and knowledge about transgender people. As a participant articulated:

They don't even think they're saying the wrong thing. They're ignorant. And you're just supposed to take it and if you did complain they wouldn't know what you were talking about. They'd act like ‘Did I say that?’

Other participants felt that health professionals deliberately targeted transgender people. As a participant explained, “they know in their job they can't discriminate, but they do. And they know they're doing it” (Transgender participant 13). There were several stories shared about health professionals not addressing transgender participants by their preferred name and/or gender. The humiliation of this experience is evidenced in the following narrative:

To go see a counsellor, they have to respect my gender. They have to call me she, not he. I've been sitting in the rooms where there have been ten or twelve people and a person has come up and said “Mr. Smith”. And when they do that, you die at that point. You're going to crawl into a hole. (Transgender participant 3)

Participants felt such mistakes were often intentional, “you know when somebody messes up on a name and it's not by accident. You know when somebody does it just for spite, to embarrass you, or to belittle you. You can tell it in the tone of their voice” (Transgender participant 12). This discrimination also resulted in reduced access to healthcare, “if they're not talking about your gender then they're saying ‘Oh, no we don't have somewhere for somebody like you’. They make you feel guilty” (Transgender participant 8).

Respect and inclusion were highlighted as essential components of competent healthcare. A transgender participant (7) explained, “I personally need respect. Just say my last name and that's it. And that way I know you're speaking to me. That's more respectful to me than saying Mr. It's less embarrassing”. Another participant narrative elucidates the importance of acknowledging transgender persons on healthcare forms, “if you give me a form and it doesn't say transsexual or transgender, you get that form back very quickly” (Transgender participant 3).

Underrepresentation in HIV research

Lesbian, bisexual and queer and transgender focus group participants highlighted exclusion from HIV research and a need for research to be translated into action.

Constrained visibility in HIV discourse

Participants invoked the limited engagement of sexual minorities and transgender women in research as indicative of their marginalization in society at large and also HIV services. As a LBQ participant (5) articulated:

Attention is given more to gay men, even the research that I've seen is more focused on gay men than women. I think we are out there missing out. There are so many role models in the gay men society, and they are doing it like in the open. I mean it's just a normal thing. But in the women part, it is so much hidden.

A participant's narrative reflects frustration with this exclusion:

I was at city hall this morning at a presentation and all they talked about was MSM, heterosexuals. I stood up and said: “I'm twenty-three years HIV-positive. When am I going to see some statistics up there for transsexual and transgender people? I don't want to wait another fucking twenty-three years to see a statistic” (Transgender participant 3).

Participant accounts indicated that when they were included in research, they often felt exploited, “we're their science project” (Transgender participant 10) and dehumanized, “we're basically rats to them” (Transgender participant 4). Participant narratives illustrated the need for researchers to avoid the construction and imposition of identity/HIV categories:

I don't need someone with a clipboard telling me because they're doing the research that I'm in this category now. Bullshit on that. Anybody who has this disease [HIV] shouldn't be able to be put in a box or a poster child for it. It's too long that we're talking about language still. These are real people with real lives. (Transgender participant 12)

Meaningful engagement emerged as a vital component of respectful research. Participant narratives highlighted the importance of listening to people living with HIV, “people who are living it, let them tell the true stories” (Transgender participant 7); researching issues relevant to participant's lives, such as sex work, “you should really do research on what the girls do for a living when we're working the streets” (Transgender participant 10); and providing research participants with appropriate financial compensation:

Offer monetary incentives for people to step out of their shadow. Especially when you're talking about people who are on disability, people who don't make a lot of money, people who live in poverty. (Transgender participant 3)

Confidentiality was discussed as an important concern for researchers to address, “let them [research participants] know that if they're contributing, people will not be judging them, people will not be discriminating against them and whatever goes on with that focus group stays within that. As long as people know that, people will start coming forward” (Transgender participant 12). Participant narratives belied a perception that involvement in HIV research could challenge their marginalization, “Research is a positive step, a good way to bring out the voices of women who are queer, because they are forgotten, I can say that. It's good that you're doing this research” (LBQ participant 5).

Need for knowledge-to-action

The belief that research could directly benefit participants emerged as a key facilitator of research participation: “for me to participate I need to know how will I benefit from the research, and how will other women benefit from the research” (LBQ participant 6). Participant narratives revealed the salience of research being translated into action, “after we identify our needs and priorities, hopefully something will be done about it and we will not be ignored anymore” (LBQ participant 3). Research could also be used to generate evidence to support community organizations’ funding applications. As a participant articulated, “there should be more grants given out and more surveys done, and I'm hoping someone can listen to this in the government because essentially we need more funding” (Transgender participant 9).

Discussion

This study's exploration of challenges in daily life and experiences in accessing healthcare among HIV-positive LBQT women revealed a trajectory of marginalization. Structural risk factors for HIV infection included social exclusion and violence [11,40,48]. HIV prevention was not tailored for, or easily accessed by, LBQT women – this further exacerbated HIV risk. Once infected with HIV, LBQT women faced interlocking barriers (e.g. HIV-related stigma, heteronormative assumptions and discriminatory treatment) that reduced access to HIV care and support. HIV-positive LBQT women's underrepresentation in HIV-research further contributed to social exclusion. Feeling excluded from HIV research, however, was coupled with the willingness to participate in research as long as findings were translated into action.

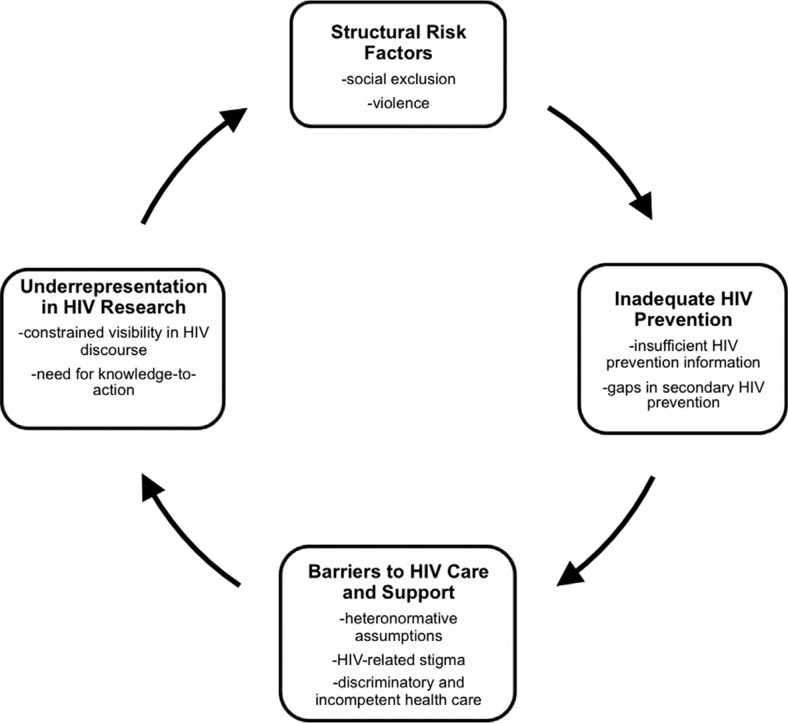

A conceptual framework that incorporates all of the themes in our analyses and their interrelationships is illustrated in Figure 1. We categorized the themes and sub-themes (Table 2) across the trajectory of HIV infection, from pre-HIV infection (structural risk factors, insufficient HIV prevention information), to post-HIV infection (gaps in secondary HIV prevention, barriers to HIV care and support), to the generation of scientific knowledge (underrepresentation in HIV research). This suggests that the experiences of HIV-positive LBQT women may change and emerge over the life-course but are significantly shaped by marginalization. The framework illustrates a cycle, in which underrepresentation in HIV-research promulgates the invisibility of LBQT women – and therefore contributes to their subsequent exclusion from HIV prevention, care and support. Scant research attention also perpetuates the lack of understanding about the lived experiences and needs of HIV-positive LBQT women. This model may be useful for future research focused on social, structural and clinical factors that influence HIV risk, healthcare access and the wellbeing of LBQT women.

Figure 1.

Themes that emerged across the trajectory of marginalization experienced by HIV-positive lesbian, bisexual, queer and transgender women (n=23).

The current study's findings are supported by previous qualitative research in the United States that highlighted the invisibility and lack of services to meet the needs of HIV-positive WSW [1,2,5]. The exclusion of HIV-positive LBQT women reported in HIV research, services and programmes corroborates previous work that highlights the assumptions in HIV “gender” works that women living with HIV are heterosexual and cisgender [2,7,31]. The lack of knowledge and policies regarding transgender people in Ontario has been described as “erasure” [31]. Our conceptualization of a trajectory of marginalization includes incompetent healthcare and constrained visibility in research, placing the concept of erasure of HIV-positive lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) women in a context of HIV risk, prevention, treatment, care and research.

Findings support the importance of using an intersectional, theoretical approach to understand the complex interactions between HIV-positive LBQT women's identities [38,39]. Homo/transphobia, sexual stigma and HIV-related stigma interacted to exacerbate marginalization among participants. Findings underscored the salience of understanding the pervasiveness of HIV-related stigma within LBQT and HIV movements, the intersection of HIV-related stigma with ethno-cultural identities and the importance of challenging transphobia and cisnormativity in both heterosexual and sexual minority communities.

Limitations of this study include a small sample size, different group sizes and socio-demographic composition between the LBQ and transgender groups. As LBQ women were included in the same focus group, it was not possible to differentiate experiences between these identities. Transgender identity and LBQ sexual orientation are also not mutually exclusive and the transgender focus group discussion primarily focused on transgender identity. Further studies are warranted to explore differences between LBQ identities and sexual minority transgender people. More in-depth training in focus group facilitation could have strengthened the PRA ability to probe participant statements. The transgender focus group (n=16) exceeded the recommended maximum of 10 participants per focus group [43,44]. Hence, there was limited opportunity for each participant to share insights and observations, and participants may not have felt comfortable speaking in such a large group [43]. The congruency between this study's findings and previous research with HIV-positive LBQT women, however, supports the validity of findings.

A strength of this study is the inclusion of diverse HIV-positive LBQT women who are underrepresented in HIV research. Findings from this study are unique as they illustrate that LBQ and transgender women living with HIV share similar experiences of marginalization. Both the LBQ and transgender groups reported social exclusion and violence, insufficient HIV information, HIV-related stigma and underrepresentation in HIV research. However, certain themes were more pronounced in the LBQ group, such as heterosexism in HIV-positive women's support groups. Transgender participants were more likely to discuss exclusion from gay/lesbian communities, difficulties in negotiating safer sex and discriminatory, incompetent healthcare. Horizontal communication between focus group participants facilitated the sharing of personal experiences of exclusion, violence and marginalization [43,44]. It is critical to address the unique challenges facing each population while also understanding commonalities in experiences of social/structural marginalization.

Conclusions

Previous conceptualizations have fruitfully documented social and structural factors, such as violence and gender norms, implicated in enhancing cisgender heterosexual women's HIV infection risks [49–51]. Only limited attention has been paid to the experiences of LBQT women [2,5,9,31]. This study expands on this literature to suggest that not only do social and structural factors elevate HIV risk among LBQT women but they also limit access to HIV prevention and present barriers to HIV care and support. Lack of engagement of LBQT women in HIV research perpetuates this cycle of marginalization. The conceptualization of a trajectory of marginalization enriches the discussion of marginalization across the life-course of LBQT women and underscores the necessity of including LBQT women in HIV prevention, care, support and research.

Intersectional interventions are required to reduce the marginalization of LBQT women. Such interventions should operate across micro, meso and macro levels of change; for example, it is necessary to challenge intersectional marginalization (e.g. heterosexism, cisnormativity) in HIV programmes/research while simultaneously addressing socio-cultural contexts of social exclusion and violence. Interventions on a micro-level could provide LBQT women with appropriate information regarding HIV risk factors, tailored safer sex information and build safer sex negotiation skills. On a meso-level, interventions can aim to reduce social exclusion by building social networks and support groups for LBQT women; challenging HIV-related stigma in predominately HIV-negative LBQT support groups and heterosexism/cisnormativity in HIV-positive women's support groups; confronting norms that reinforce transphobia and cisnormativity in lesbian, gay and bisexual communities; and addressing stigma, discrimination and violence targeting sexual minorities and transgender people in the society at large. Macro-level interventions should provide anti-discrimination and cultural competence training for healthcare professionals regarding LBQT women's health, training on LBQT women's sexual health needs and HIV risks in sexual health clinics and ASO training to challenge heterosexism/cisnormativity in services for HIV-positive women.

Research has the potential to call attention to structural HIV risk factors – as well as inform and evaluate treatment, care and support [11,12,40,48]. Future community-based research should be conducted in partnership with diverse HIV-positive LBQT women to design, implement and evaluate HIV prevention, care and support services tailored for LBQT women. As HIV researchers, we should examine our own biases to ensure we include space for sexual minorities and transgender women to participate (e.g. in socio-demographic forms, targeted recruitment) [2,5,9,19]. HIV prevention, care, support and research needs to better address the needs of LBQT women to promote health equity.

Acknowledgements and funding

We acknowledge all of the women who participated and shared their time, knowledge and experiences as PRA and focus group participants. We are also thankful for the Community Advisory Board Members. We are grateful to the E.D., staff and research coordinators at Women's Health in Women's Hands Community Health Centre. We thank Tonia Poteat (PhD, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health) for reading and providing feedback on the earlier drafts of this article. This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). CHL was remunerated for writing this manuscript through a CIHR fellowship. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

WT and MRL were principal investigators and designed the study. CHL and LJ collected data. CHL and LJ conducted data analysis. CHL conceptualized and led writing of this manuscript. ML, LJ and WT provided feedback/edits. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Arend ED. The politics of invisibility: homophobia and low-income HIV-positive women who have sex with women. J Homosex. 2005;49(1):97–122. doi: 10.1300/J082v49n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dworkin SL. Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7(6):615–23. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marazzo JM. Dangerous assumptions: lesbians and sexual death. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(9):570–1. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175368.82940.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrow KM, Allsworth JE. Sexual risk in lesbians and bisexual women. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 2002;6(1):159–65. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson D. The social construction of immunity: HIV risk perception and prevention among lesbians and bisexual women. Cult Health Sex. 2000;2(1):33–49. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins JA, Hoffman S, Dworkin SL. Rethinking gender, heterosexual men, and women's vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):435–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landers S, Gruskin S. Gender, sex, and sexuality—same, different, or equal? Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):397. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.188169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauer GR, Welles SL. Beyond assumptions of negligible risk: sexually transmitted diseases and women who have sex with women. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1282–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.8.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marrazzo JM. Sexually transmitted infections in women who have sex with women: who cares? Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:330–2. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.5.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto V, Tancredi M, Neto A, Buchalla C. Sexually transmitted disease/HIV risk behaviour among women who have sex with women. AIDS. 2005;19(S4):S64–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000191493.43865.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Auerback JD, Parkhurst JO, Caceres CF. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: conceptual and methodological considerations. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(S3):S293–309. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.594451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kippax SC, Holt M, Friedman SR. Bridging the social and the biomedical: engaging the social and political sciences in HIV research. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14(S2):S1. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-14-S2-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Logie C. The case for the World Health Organization's Commission on the Social Determinants of Health to address sexual orientation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1243–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer IH. Why lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender public health? Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):856–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fethers K, Marks C, Mindel A, Estcourt ES. Sexually transmitted infections and risk behaviours in women who have sex with women. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:345–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.5.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman SR, Ompad DS, Maslow C, Young R, Case P, Hudson SM, et al. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, and high-risk sexual and injection networks among young women injectors who have sex with women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):902–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bevier PJ, Chiasson MA, Heffernan RT, Castro KG. Women at a sexually transmitted disease clinic who reported same-sex contact: their HIV seroprevalence and risk behaviors. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(10):1366–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.10.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bailey JV, Farquhar C, Owen C, Mangtani P. Sexually transmitted infections in women who have sex with women. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:244–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.007641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer GR, Jaram JI. Are lesbians really women who have sex with women (WSW)? Methodological concerns in measuring sexual orientation in health research. Women Health. 2008;48(4):383–408. doi: 10.1080/03630240802575120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young RM, Meyer IH. The trouble with ‘MSM’ and ‘WSW’: the erasure of the sexual-minority person in public health discourse. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1144–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keiswetter S, Brotemarkle B. Culturally competent care for HIV-infected transgender persons in the inpatient hospital setting: the role of the clinical nurse leader. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):272–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNAIDS. UNAIDS action framework: Universal access for Men who have Sex with Men and Transgender People; Switzerland, Geneva: UNAIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviours of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clements-Nolle K, Marx R, Guzman R, Katz M. HIV prevalence, risk behaviors, health care use, and mental health status of transgender persons: implications for public health intervention. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):915–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemoto T, Operario D, Keatley J, Han L, Soma T. HIV risk behaviors among male to-female transgender persons of color in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(7):1193–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thornhill L, Klein P. Creating environments of care with transgender communities. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilson EC, Garofalo R, Harris RD, Herrick A, Martinez M, Martinez J, Belzer M. Transgender female youth and sex work: HIV risk and a comparison of life factors related to engagement in sex work. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(5):902–13. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9508-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clements-Nolle K, Guzman R, Harris SG. Sex trade in a male-to-female transgender population: psychosocial correlates of inconsistent condom use. Sex Health. 2008;5(1):49–54. doi: 10.1071/sh07045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Operario D, Soma T, Underhill K. Sex work and HIV status among transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(1):97–103. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e3971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sevelius JM, Carrico A, Johnson MO. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among transgender women living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2010;21(3):256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauer GR, Hammond R, Travers R, Kaay M, Hohenadel KM, Boyce M. I don't think this is theoretical; this is our lives’: how erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):348–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.UNAIDS. Reducing HIV Stigma and Discrimination: a critical part of national AIDS programmes; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herek GM. Confronting sexual stigma and prejudice: theory and practice. J Soc Issues. 2007;63(4):905–25. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fish J. Far from mundane: theorising heterosexism for social work education. Social Work Education. 2008;27(2):182–93. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herek GM. Thinking about AIDS and stigma: a psychologist's perspective. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(4):594–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2002.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Serano J. Emeryville, Seal. 2007. Whipping girl: a transsexual woman on sexism and the scapegoating of femininity. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowleg L. When black+lesbian+woman≠black lesbian woman: the methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles. 2008;59:312–25. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins PH. Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crenshaw K. Univ Chic Leg Forum. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics; pp. 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Logie CH, James L, Tharao W, Loutfy MR. HIV, gender, race, sexual orientation and sex work: a qualitative study of intersectional stigma experienced by HIV-positive women in Ontario, Canada. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):1001124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruger KA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morgan DL. The focus group guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mertens DM. Research and evaluation in education and psychology: integrating diversity within quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trochim WMK, Donnelly JP. The research methods knowledge base. 3rd ed. Mason, Ohio: Cengage Learning; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res. Psych. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(1):S3–10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amaro H, Raj A. On the margins: the realities of power and women's HIV risk reduction strategies. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7/8):723–49. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lane SD, Rubinstein RA, Keefe RH, Webster N, Cibula DA, Rosenthal A, et al. Structural violence and racial disparity in HIV transmission. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(3):319–35. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2004.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(4):911–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]