Abstract

Background

Living with HIV is of daily concern for many South Africans and poses challenges including adapting to a chronic illness and continuing to achieve and meet social expectations. This study explored experiences of being HIV-positive and how people manage stigma in their daily social interactions.

Methods

Using qualitative methods we did repeat interviewed with 42 HIV-positive men and women in Cape Town and Mthatha resulting in 71 interviews.

Results

HIV was ubiquitous in our informants’ lives, and almost all participants reported fear of stigma (perceived stigma), but this fear did not disrupt them completely. The most common stigma experiences were gossips and insults where HIV status was used as a tool, but these were often resisted. Many feared the possibility of stigma, but very few had experiences that resulted in discrimination or loss of social status. Stigma experiences were intertwined with other daily conflicts and together created tensions, particularly in gender relations, which interfered with attempts to regain normality. Evidence of support and resistance to stigma was common, and most encouraging was the evidence of how structural interventions such as de-stigmatizing policies impacted on experiences and transference into active resistance.

Conclusions

The study showed the complex and shifting nature of stigma experiences. These differences must be considered when we intensify stigma reduction with context- and gender-specific strategies focussing on those not yet on ARV programmes.

Keywords: HIV stigma, South Africa, discrimination, living with HIV, internalized stigma, perceived stigma

Background

Living with HIV is of daily concern for many South Africans, and the challenges they face include adapting their lives to live with a chronic illness whilst continuing to achieve or meet social expectations including being economically independent, have intimate relationships, assessing risks, protecting others and adhering to treatment. The availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) globally has resulted increasingly in perceptions that HIV infection and AIDS are manageable chronic health problems [1–3], but in many countries too few people know their status and are coming forward in time for treatment and HIV stigma remains one of the greatest challenges to service delivery [4,5]. Overall studies from across the globe including a meta-analysis found lack of support, poor mental health, lower age, lower income, poor physical health, non-disclosure, low adherence, poor knowledge, health and economic resources associated with higher levels of stigma [2,6–10].

The early work of Erving Goffman [11] provided the theoretical base from which the phenomena of stigma has become conceptualized when he described it as a powerful social label that discredits and taints the way individuals view themselves and the way they are viewed by others. This initial conceptual framework evolved as attempts were made to more clearly define, conceptualize and measure HIV status in particular in efforts to develop effective interventions [12–15]. In an extensive analysis of the HIV stigma theories, Deacon et al. [16] highlight the polarity of the construct with it either viewed within individual psychological terms [11,13] or as a form of social control where it is seen as a reinforcement of existing social inequalities [4,14,17], with both failing to adequately incorporate each other and its complexities. There is no doubt that stigma interacts with social inequalities, but many of the sociological explanations viewed HIV stigma only in terms of its discriminatory impact [4,14] and the terms have become critiqued to be conceptually inflated [18–21] with endless inclusion as Prior et al. noted stigma “… is creaking under the burden of explaining a series of disparate complex and unrelated process …” [20] (p 2192). The lack of consensus impacted on research and development of effective interventions [19], and in seeking to better conceptualize HIV stigma Deacon et al. [16] separate stigma from its responses and its effects and provide a definition of stigma outside of the framework of discrimination (enacted stigma) because not all stigma ideas result in discrimination and not all discrimination arise from stigma. In this theoretical framework, internalized/self-stigma is also viewed as an effect of stigma and includes perceptions and actions that stem from the persons’ own negative views of their HIV status. Self stigma arises from perceived/expected stigma. Deacon et al. [16] further introduce the “blaming” model of stigma which brings together the social and the individual concepts and is based on research on risks which explains stigma as an emotional response of fear to danger and uncertainty and where a sense of control and safety is created through distancing and projecting blame on identifiable “out-groups” – these groups often reflecting wider social inequalities.

The variability in the concept and measurement makes the assessment and comparison of the huge body of research that emerged globally and in South Africa difficult [19,21]. A study among people living with HIV in Cape Town measured discriminating experiences and showed 45% of the men and 40% of the women had such experiences [22] while a second South African household study with repeat interviews showed that behavioural discriminatory intentions moved from 2% in 2003 to 11% in 2006 [23]. This study however changed their measurement tool. In a household study across five sites (n=14,367) (two in South Africa: Soweto & Vulindlela), South Africa scored the lowest mean scores for negative attitudes and beliefs compared with Thailand, Tanzania and Soweto [2]. Evidence of stigma decline has however been reported from studies with different study designs and populations including the South African National HIV study [24] that reported a decline between 2003 and 2005. Improved care and treatment has been cited as contributing to the decline. However recent the South African studies with improved measurement of internalized stigma have shown that this form of stigma remained constant over a period with lower CD4 counts and depression associated with this type of stigma [9,25].

Despite the increasing number of South Africa studies on stigma, most use quantitative methods measuring levels of stigma and only few explore the daily social reality of HIV-positive people. More recent qualitative research has started to shed the light on contextual factors and the multiple dimensions of stigma experiences with many exploring experiences of caregivers [26–29] where lack of support and economic resources appears to contribute most to the burden while a number of studies have started to show how acceptance of the disease and attempts to attain normalcy are being sought [30,31]. Gender as a broad concept has been recognized as an important form of social and structural inequality that interacts with stigma [4,14,16], and analysis by gender in measurement studies has been performed in South Africa and elsewhere with mixed results [9,22,25,32] (albeit same questions asked for both men and women), but the meanings and contexts of perceived, self and enacted stigma for men and women have not received much research attention.

It is critical to understand the experiences of being HIV-positive and of being on ART [16] because this provides a better understanding of the circumstances of disclosure and the support networks of HIV-positive people. A more thorough understanding of the different ways in which men and women experience HIV and how this impacts on their daily social interactions is critical for better theoretical and conceptual understanding of how HIV impacts on the social lives of people. It has become recognized that stigma is a complex social process that is ever changing and sometimes even resisted, and in this article we present findings of a qualitative research that explored how being HIV-positive impacts on the lives and strategies of HIV-positive individuals to manage, build and maintain social relations.

Methods

We conducted a study between 2006 and 2007 in two diverse sites: Cape Town an urban city and Mthatha, a growing rural town in the Eastern Cape Province. These two towns differed geographically, by health, by development indicators, by health service delivery and prevalence of HIV infection [33]. The study site in urban Cape Town was an HIV clinic in one of the older Cape Town townships. The clinic had dedicated medical, nursing and pharmaceutical staff, patient advocates and adherence counsellors, and support networks with HIV and community organizations. In addition to medical indicators, one of the main requirements for admission to the ART programme was evidence of social support in the form of a treatment buddy to whom patients could disclose their status and get support. The patient advocates also played important supportive roles particularly at the commencement of the treatment and in ongoing support. Each patient was allocated a patient advocate at the commencement of their ART, who worked closely with the clinical staff to ensure optimal and holistic care. We used a variety of recruitment processes in Cape Town. Patients were approached while they sat waiting in the clinic, patient advocates were asked to introduce the study to their patients, and patients were asked if their contact details could be forwarded to a researcher (written consent for contact details to be forwarded were done and full consent done later by researcher), and we also allowed snowballing when participants volunteered to introduce us to their friends and family. Most of the participants from this site were on the ART programme, while a few were on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis only (see Table 1). The 21 participants from Cape Town were mostly born in Cape Town or lived there for a while, although a few had moved from the Eastern Cape for better health services. All were Black African and Xhosa speaking, and most lived in the main township with just a few living in the surrounding areas. Their houses were typical of the area's township houses; either four-roomed brick walled houses or in backyard corrugated iron shacks.

Table 1.

Description of sample

| ID | Sex | Age | No. of interwiews | Treatment | Employed | Children | Relationship status | Partner HIV status | Disclosed partner | Disclosed family/friends/ | Close family/friends positive | ID | Sex | Age | No. of interviews | Treatment | Employed | Children | Relationship status | Partner HIV status | Disclosed to partner | Disclosed family/friends/others | Close family/friends positive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | F | 28 | 2 | ART 16/12 | No | Yes | Dating | Pos | Yes | Fa-S Fr-S | No | E1 | F | 22 | 2 | No | No | Yes | Dating | Ukn | Yes | Fa=S Fr-S | Yes |

| C2 | F | 34 | 2 | ART 48/12 | No | Yes | Broke-up C Single | Ex-Ukn- | Ex-Yes | Full | Yes | E2 | F | 19 | 1 | No | No | Yes | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C3 | M | 38 | 3 | ART 36/12 | Yes | Yes | Dating | Pos | Yes | Full | No | E3 | F | 24 | 2 | No | No | Yes | Dating | Yes | Yes | Full | No |

| C4 | F | 36 | 2 | ART 20/12 | No | Yes | Single | _ | _ | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E4 | F | 23 | 2 | No | No | No | BF died | Yes | Yes | Full | No |

| C5 | F | 39 | 2 | ART 29/12 | No | Yes | Cohab | Ukn | Yes | Fa-N Fr-S | Yes | E5 | F | 24 | 1 | No | No | Yes | Married | Ukn | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C6 | F | 29 | 2 | ART 15/12 | No | Yes | Single | _ | _ | Full | Yes | E6 | F | 20 | 2 | ART | No | No | BF died | Yes | Yes | Full | No |

| C7 | F | 30 | 1 | Prop | Yes | Yes | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-S Fr-S | No | E7 | F | 25 | 1 | Tb Rx Prop | No | Yes | Single | Ukn | Fa-S Fr-N | No | |

| C8 | F | 28 | 2 | ART 12/18 | No | Yes | Cohab | Pos | Yes | Fa-S Fr-S | No | E8 | F | 25 | 2 | Art | No | Yes | Married | Yes | Yes | Full | No |

| C9 | F | 24 | 2 | ART 12/12 | Yes | No | Broke-up C Dating | Ex-Ukn C-Ukn | Ex-Yes No | Fa-S Fr-S | No | E9 | F | 22 | 1 | No | No | No | Dating | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| C10 | F | 22 | 1 | ART 42/12 | No | Yes | Married | No | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No | E10 | F | 24 | 2 | No | No | Yes | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-S Fr-S | No |

| C11 | F | 34 | 1 | ART 16/12 | Yes | Yes | Broke-up C-single | Ex-Ukn | Ex-Yes | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E11 | F | 22 | 2 | No | No | Yes | Married | Ukn | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C12 | F | 32 | 2 | ART 13/12 | Yes | Yes | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-S Fr-N | No | E12 | F | 21 | 2 | No | No | Yes | Dating | Ukn | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C13 | F | 25 | 3 | ART 33/12 | No | Yes | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E13 | F | 21 | 1 | No | No | Yes | Married | Yes | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C14 | F | 30 | 1 | Prop | No | No | Single | Ukn | Yes | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E14 | F | 25 | 2 | Prop | No | Yes | Single | Yes | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C15 | F | 30 | 1 | ART 21/12 | No | yes | Dating | Pos | Yes | Full | Yes | E15 | F | 23 | 1 | Prop | No | Yes | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C16 | M | 33 | 2 | ART 30/12 | No | Yes | Cohab | Pos | Yes | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E16 | M | 25 | 2 | No | No | No | Dating | Ukn | No | No | No |

| C17 | F | 33 | 1 | Prop | Yes | Yes | Cohat | Ukn | Yes | Fa-N Fr-S | Yes | E17 | M | 27 | 2 | No | No | No | Dating | No | Yes | Fa-S Fr-N | No |

| C20 | M | 29 | 1 | TB Rx Prop | Yes | Yes | Dating | Pos | Yes | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E18 | M | 24 | 1 | No | No | No | Dating | Ukn | No | Fa-N Fr-S | No |

| C21 | F | 28 | 2 | Prop | Yes | No | Divorce C-Dating | Ex-Pos C-Ukn | Ex-Yes C-No | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E19 | M | 23 | 2 | Prop | Yes | No | Dating | Ukn | Yes | Full | No |

| C22 | F | 32 | 1 | ART 35/12 | No | Yes | Cohab | Yes | Yes | Fa-N Fr-S | Yes | E20 | M | 23 | 1 | Prop | No | No | Single | No | No | ||

| C23 | F | 27 | 1 | Prop | No | Yes | Broke-up C-Dating | Ex-Pos C-Ukn | Ex-Yes C-No | Fa-S Fr-S | Yes | E21 | M | 21 | 1 | No | No | No | Dating | Ukn | No | No | No |

C1–C23=Cape Town participant; E1–E21=Eastern Cape participant; M=Male; F=Female; ART=AntiRetroviral Therapy; C=current; Ukn=Unknown; Pos=Positive; Neg=Negative; Cohab=Cohabiting; Prop=prophylaxsis; TBRx=TB treatment; S=Selective; Full=Full disclosure; N=No; BF=Boyfriend; GF=Girlfriend; Fa=Family; Fr=Friend.

The second group of participants (n=21) lived in and around Mthatha, Eastern Cape. This Province is primarily Xhosa-speaking and highly impoverished. Unemployment is rife and infrastructure and services are poor. All participants had learnt their HIV status when participating in the randomized controlled trial in the period 2002–2006 to evaluate the HIV prevention behavioural intervention Stepping Stones [34]. They had been recruited from schools and had been tested for HIV in the course of the study. The project had two study nurses who provided psychological support to participants through a 24 hour cell phone line, and those who tested HIV-positive were also financially supported to access healthcare when needed. Participants in this study came from both study arms and had been offered a 3 hour session on HIV and safer sex. Those in the main intervention arm had received this as part of a 50 hour intervention. All these participants had been enrolled in the present study after indicating an interest in being invited to participate for further research. The 21 participants were positive, knew their status and had agreed to be contacted again. The field nurse from the original trial asked them if they wanted to participate in this study. The participants in the Stepping Stones trial had been given R20 (about $3) for each interview and so there may have been an expectation of some material reward.

This qualitative study used semi-structured, in-depth interviews with the 33 women and 9 men (see Table 1). We conducted participant observation at the Cape Town site, and a focus group discussion was also held among four women in Cape Town (on their request). Many participants had repeat interviews, with between one and three interviews per person, resulting in a total of 71 interviews (33 from Mthatha and 35 from Cape Town). The repeat interviews were dependent on the willingness and availability of the participants and allowed for building of rapport as well as further probing during the second interview. The interviews ranged from 30 to 90 minutes.

The scope of inquiry for the interviews covered feelings about being HIV-positive; the process of disclosure and decisions about disclosure; stigma experiences and responses from others including partners, family and friends; how they dealt with stigma; communication about HIV and management of their health. The set of probes for the second interviews were developed after transcription and initial analysis of the first interview. This allowed us to clarify issues that came up with other participants and also extended our scope of inquiry for the rest of the interviews.

The interviews were staggered to allow for the translation, transcription and initial analyzes to occur. The interviews were audio-recorded and conducted in the respondent's preferred language, mostly isi-Xhosa, but a few were in English. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and translated into English in preparation for analysis. Extensive field-notes were developed after each interview as well as during participant observation. The analysis used content analysis and analytical induction, with coding initially following the main sections of the scope of inquiry and thereafter using analytical induction with sub-codes emerging from the data. We further continued with analytic induction to generate and test mini-hypotheses in the data and to search for deviant cases [35]. All interviews were kept confidential, and the data were analyzed in a way that informants were not identified. Ethical approval for the study was given by the Medical Research Council's Ethics Committee.

Results

Table 1 describes some of the key aspects of the study participants’ lives and some of their demographic, health and social characteristics. The participants from the Mthatha site were generally 10 years younger (average of 23 vs. 33 years) and most had learnt their status when healthy, in contrast to those from Cape Town who had mostly discovered their status in antenatal care or when very ill, in the latter case many had dramatic stories of recovery from severe illness.

Accommodating HIV into their lives

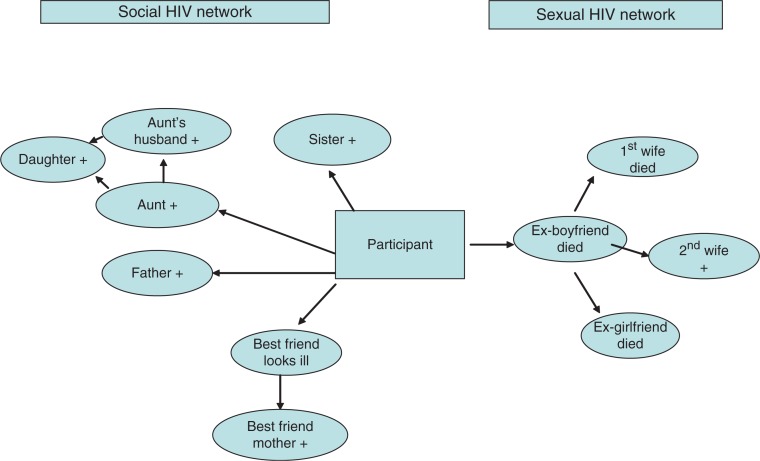

In having been infected with HIV, participants asserted that they were not unusual. Most viewed it as ubiquitous in their communities, and said that it had been easy to accept the diagnosis because “many people have HIV”. One person from Mthatha had a rather extreme perception that “only 5% of the people do not have it”. One of the reasons why it was perceived in this way was that many urban participants (but just one from Mthatha) had other family members who were positive (fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers, cousins and children). Close bonds with HIV-positive sisters were described in particular, and ensured that HIV became part of their daily lives not just of themselves, but of their social networks as well. The HIV network of one urban participant is shown in Figure 1. This demonstrates the supportive network she developed as well as the pervasiveness of HIV infection in her community.

Figure 1.

Social and HIV network of a Cape Town-based participant.

Assertions of normality were strong indications of the way in which HIV had been accommodated into the participants’ lives, and most participants spoke of the support they received from families. Experiences of perceived HIV stigma were described, but they did not dominate the participant's conversations about hardships in daily life or as a “potent and painful force” as stigma was described by Goffman [4]. The dominant challenges of daily living they described were the typical problems faced by South Africa's poor, such as the struggle to find employment, housing, negotiating relations with families and struggles within intimate relationships. Sometimes being HIV-positive had exacerbated these problems. This was especially true for a few women who had been left by their partners after they disclosed their status (see more later). A 30-year-old Cape Town woman said:

I am struggling and sometimes even at home I don't have anything [to eat]; it's been a long time since I've been out of work so I'm really struggling. I always tell myself that I'm going to be fine, but it's hard because I'm really struggling [she cries]. My status is no longer my worry because I have accepted it. Even at home they have accepted me and are supporting me. Things didn't go well with my baby's father because after I told him about my status he just went to marry another woman.

Such abandonment was not viewed by the women as arising from stigma or a form of HIV discrimination because fluid relationships were a common phenomenon, and research has shown that women do not expect much in terms of commitment from relationships [36].

Stigma, fear and disgrace

Participants were very aware of HIV stigma and the potential for discrimination (perceived stigma), and many had observed acts of stigmatization of others. As a result they were fearful of being “hurt”. A young man from Mthatha described observing his friend being insulted saying “His mother always insulted him about his status and said, hey Nompuku, this thing that has got AIDS …”. Another explained that student friends at his college would “distance themselves … once a person looks like he is sick they just assume that and they start running away”. Some of the participants had found themselves at times “suffering” when friends gossiped about people living with HIV, as one man said: “I also notice that when I am with my friends in the location that you will find out that most of the time they are criticizing the people who are positive”. These interactions show participants not experiencing discrimination, but observing it targeted at others and although this appeared not to have led to internalized stigma, it seemed to have influenced decisions around disclosure, care seeking and accessing future support.

In an account of having observed the neglect and ridicule of a very ill neighbour, a woman said:

her neighbours didn't know, but they were assuming that she's HIV … they were laughing at her. I mean you'd find that someone goes to see her as if s/he sympathizes with her. But s/he actually goes there to laugh at her. There was no-one who took care of her, no-one from her family came forward … even when she was dead nobody from the family came to take her. So people collected some cents/money to bury her.

In this case HIV stigma and discrimination intersected with socio-economic disadvantage which have been described in the South African literature [26,28], but none of the participants experienced similar treatment. This demonstrates how HIV stigma and discrimination operates at many levels – within the social group as well as at individual behaviours [5,16].

Many of the women mentioned fear of being morally judged for being HIV-positive. A 23 year old from Mthatha explained that if her status was known “I would be a disgrace in the location, a disgrace … People would say ‘What did you expect from so and so's child, knowing that she stays alone’”. Another feared being blamed and told it was “because I used to jol [party] too much”. This was apparently also a fear of their families, with more than one participant from Mthatha [all women] indicating that their parents discouraged them from disclosing their status, and prevented them from attending support groups, because of their fear of being “disgraced”.

Moral judgment of HIV positivity was reserved for women. None of the men or their families expressed concerns about being labelled promiscuous. This is perhaps unsurprising in the context of the South African gender regime where conspicuous displays of heterosexuality are regarded as a central part of hegemonic masculinity [37]. Apart from fearing general insults, young men from Mthatha feared that knowledge of their status would be used by their family to curb their independence. One said “I decided not to tell them [parents] so that they don't have a say in my life”. Independence is also seen as important in hegemonic masculinity, and thus men perceived that their HIV status threatened their gendered sense of self in a range of ways.

Stigma, gossip, insults and resistance

Fear of other people's responses to their HIV status was not confined to moral judgment only, but also encompassed fear of ridicule, being “laughed at for being HIV +”. All the participants except three were concerned about people's perceptions of their HIV status. In small South African communities gossip can be a powerful force, and by its nature it is often strikingly lacking in compassion and empathy, and thus very hurtful. Such were the expectations of gossip that one woman explained:

At the beginning I used to think that people see through me, it's like they could see that I'm HIV+… now I know that they don't know because I know how people are. If they knew they would be teasing or insulting me about it.

Whilst the perception that people could “see through her” and see the HIV is commonly described as part of the early reaction to an HIV+diagnosis, the fact that she was not teased does not mean that people did not know her status, as many participants spoke of positive reactions from people when they disclosed and in this context mentioned “they did not make me funny” [were not laughed at].

The most predominant negative experience took the form of insults during conflicts. Social relationships in South African families and neighbourhoods often become strained and erupt into loud and often violent fights. Insults and blows are often traded and exacerbated by structural factors such as poverty, unemployment, massive overcrowding and the normative practice of having multiple and concurrent partners. In such conflicts a person's HIV status would often become ammunition. This was perceived as extremely hurtful and could often also result in the HIV status becoming public knowledge.

In none of the accounts shared had the conflict ever originated directly from HIV-related matters. Another woman found her step-father using her status during fights with her mother, saying “… I'm staying with my mother and … her husband heard that I'm HIV+… So he always brought it up every time they get into a fight. He would shout so that everyone could hear [and that hurt me]”.

A Cape Town woman described an account of her active resistance to the gossip and stigma, explaining:

You know what was happening in my area? My neighbours were doing like ‘let's go and see Vumisa [not real name], I think she's sick, maybe in two weeks she's going to die’ … they were coming to visit me. Then when they come I just say ‘Hi and call them by their names, are you alright? I'm alright too but I'm HIV positive. I know you are here to see what is happening with me, I know that there's someone who told you that I am sick and you are here to check what is happening. So I'm positive, are you alright with that? Thank you, bye’. Just like that …

While still very ill and incapacitated she asked her mother to assist her to sit in a chair in the middle of the road and called the neighbourhood to come and look at her and declared her status. She also used this opportunity to speak about prevention and testing. In this case perceived or expected stigma triggered active resistance with a positive outcome, a possibility discussed by Deacon et al. [16], but not often reported in research [31,38]. Participants had a range of different approaches to resist stigma, from the very active described above to passive avoidance, as seen by a woman in Mthatha whose cousin seemed to fear contagion and did not want to share a glass with her. She responded by deciding to not visit the cousin and this withdrawal can also be seen as a form of resistance to the stigma.

A woman told of being insulted about her HIV status initially by her brothers's ex-girlfriend and then by a girlfriend of her sister's boyfriend and in the close proximity of township living the fights had resulted in her HIV status being publicly known. The matter had been resolved, initially after intervention from the police, through their (quite spurious) threat of jail for insulting the informant about her HIV status, and then by the families:

My brother's ex-girlfriend was staying next to our house and she used to make remarks about my status indirectly. That saddened me but I kept quiet and my sister used to tell me not to worry about what people say … Then my sister had a fight with her boyfriend's other girlfriend and I couldn't stand while my sister was insulted. Then this girl said to me, ‘Where's your baby's father? He died of AIDS we know that’. I just kept quiet. Then they ganged up and hit my sister … I went to fight with them as well. We went to the police station to report that they are insulting us about our status and the police gave them warning that if they do it again they will go to jail, and they apologized. Our families met and we discussed it. We are on speaking terms now

Many participants from Cape Town drew strength from an assertion that revealing someone's HIV status without their consent was a criminal offence. Most of these insults were not passively accepted with a young woman describing how she managed to successfully fight back as well as maintain her self-esteem:

I said one thing that made her (an aunt) to stop insulting me. I told her that at least I know my status, she doesn't know hers. So if she ever insults me again as she does when she's drunk, I will … go to the police … My cousins also told her that if she wants to go to jail, she must keep on insulting me and then she stopped.

Such legal interventions have been identified as an important mitigation tool for decreasing stigma [12] and it is reassuring to see threats of their use being effective in South Africa. Families were often very supportive in the face of gossip, and provided advice and support such as not disclosing status to other family members known to become garrulous when drunk or those with whom they had had previous conflicts or disagreements.

“They love me more”: stigma and family support

In contrast to the fears of reactions from those outside the family, decisions to disclose within the family were not difficult for most participants. A few were initially “scared” or unsure of family's reaction and eight of the 42 participants had not disclosed to a family member. Four of the nine men in the study had not disclosed, and whilst they all came from Mthatha, this proportion was much higher than for women and it is likely that it was chiefly a gender issue. Their concern being that HIV positivity would be read as a sign of weakness, and used as a way of trying to contain their behaviour and thus reduce their independence, both would make them feel less manly. A body of research on masculinity and HIV from South African demonstrates similar male behaviour [37,39,40]. Participants who disclosed to family described receiving overwhelming support from them and nobody was abandoned or rejected by their families. Many participants from Mthatha said that after disclosure to families the topic was not referred to again, but snippets of support were given such as words of encouragement, advice on diet and buying of vegetables and immune boosters. Affection and closeness with family is shown when a woman said “what I have observed is that they [family] love me more than they use to”.

Although mothers and older sisters were commonly described as the main supporters, a few fathers also played important roles such as being a treatment buddy for a male participant from Cape Town or providing their grant money for transport assistance to the clinic in Mthatha. Such caring roles of men have been described in the masculinity literature [41]. However in general it was not easy to disclose their status to their parents because of the link between HIV, sexual moralities and its association with death. Even when a mother, travelling from the Eastern Cape to visit her ill daughter, had said “My child, if you are HIV positive it doesn't matter” the participant and her sister decided not to tell her to “spare” her the pain of knowing. Some also wanted to protect parents whom they consider were not knowledgeable enough about HIV to understand that death is not imminent, or further burdened parents who already face other hardships such as having other HIV-infected children.

The support from brothers was also described by many participants. A woman said her brother paid her private medical aid fees, another said:

My brother was shocked, but he said he does not have a problem and then he started telling me about his friend that is also positive. He just said I should tell myself that I'm going to take my treatment and I am still going to live longer.

Another brother told a participant “Nlz being HIV+ doesn't mean it's the end of the world, you just have to look after yourself now and don't be afraid of challenges”. These positive and supportive experiences from important others facilitated the formation of new identities which allowed participants to cope and resist stigma [31,42].

Some of the young participants (both male and female) from Mthatha did not want to disclose to parents because they feared being blamed and their behaviour being controlled. A young man said “I do not want someone who is going to encourage and provide some counselling at the same time scold me maybe tell me that I am positive because I do not care. He would be upsetting me and I do not want that”. More than one young man thought knowledge of their status will provide leverage to parents to control their behaviour. This fear needs to be understood in the context of a widespread perception by older people that young people's (particularly men's) behaviour is “out of control” in the context of widespread engagement in crime, violence, heavy alcohol consumption, drug use and fathering (or having) multiple adolescent pregnancies, and parents’ ongoing worry about their sons and daughters [43]. On the other hand this may also be an indication of young participant's trying to protect their self-esteem from painful criticism.

Friendships: “Most of my friends are also HIV+ now”

Responses from friends were varied. For some, friendships continued, while more than one of the young participants from Mthatha perceived that they had become excluded by friends and were not invited to parties. This did not bother them much and many moved away from friends who demonstrated stigmatizing attitudes and new friendships were developed among people whose attitudes to HIV were not stigmatizing. A few maintained friendships as one explained “I pretend as if I am not infected”. Almost all participants at both sites subtly challenged negative HIV perceptions of friends during normal social discussions of HIV, without necessarily disclosing their status. “If they are criticizing HIV positive people then I try and tell them that those people did not invite HIV so it can happen to anyone”.

For others, friends were the only people they disclosed to. In Cape Town more than one woman chose a girlfriend as a treatment buddy and all except a woman from Mthatha had emphatic reaction when disclosing to friends. One group of four participants recruited from a support group in Cape Town requested to have their first interview together and the mutual support was evident when they teased each other about not having any secrets.

Participants described how new friendships had emerged within safe social environments such as within formal and informal support groups or even during periods of waiting together in the clinic waiting room. The construction of these new collective identities of being HIV positive allowed for reciprocal support and benefits. A woman said “most of my friends are also HIV+ now” and spoke about her sister and best friend not needing friendships outside of their new social group:

We sit there and chat about life, boyfriends and other stuff; and if one needs advice we advise her … Then we also talk about HIV … we share views and advise each other; and if you've got a pain you get pain tablets from the other one.

Gender and stigma

Surprisingly HIV stigma did not play a very disruptive role in intimate relationships. Most of the women in the Eastern Cape disclosed their status to their intimate partners (12 out of the 15 women) while only 3 of the 6 men who were in steady relationships disclosed to girlfriends and at the time of the second interviews we found all of the women who were in stable relationships had continued with their lives without major disturbance. For the four married women in Mthatha, their HIV status seemed to have solidified the marriage with one of the husband's deciding to “dump his girlfriends” another wife saying “it's been still between us” referring to the absence of conflict and the third saying “Marriage has got its own ups and downs but I never even think that those things are happening because I am HIV ‘positive’”. Only one of the husbands tested and the rest assumed proxy positivity with a wife saying “He said there is no point of going for the test because if I [wife] was positive that means he is also positive”. The married women from Mthatha all explained that they got married while still at school and because they were pregnant (two at age 15) and unequal gender relations were a notable part of the daily lives of most women at both the sites, which was most evident in their struggle negotiating use of condoms.

Of the 21 participants in Cape Town, fifteen had disclosed to their partners (all three men disclosed to their female partners) and for some women relationships continued but for a few they ended and most of them decided not to disclose when they entered new relationships. The women's narratives were replete with the challenges they faced on a daily basis to negotiate safer sex and getting partners to test. For multiple reasons relationships did not always last. Among the participants from Cape Town, one woman left her husband because of ongoing physical and financial abuse and a male participant left his girlfriend because of ongoing conflict about her alcohol drinking (both had started new relationships: the male with an HIV-positive woman while the female participant had not disclosed her status to her new partner). Three women from Cape Town reported that their boyfriends abandoned them after disclosure of their status. It appears that this abandonment was not so much related to stigma, as it was related to the men's own inability to deal with the possibility of their own HIV infection since the women asked them to take an HIV test. This is shown in two accounts from Cape Town:

I sat down with him and I told him that I'm HIV positive. He said I'm lying and I told him I can't just lie about that. I gave him a pamphlet that I got here at the clinic and I told him to come to the clinic too, but he refused and left. I thought I was advising and encouraging him to get tested, but I chased him away’. Another said ‘I told him to go for testing. I'm not saying I got it from him but he must go for testing. That was the last time I saw him, he disappeared [laughter]. Then he started to call me …. He would ask ‘Were you telling me the truth that you are HIV positive?’ and I would say yes. And I ask if he had tested or not. He would also come again and be nice to me with the hope that we will get back together again. So he just calls me, but he hasn't done the test.

Having a male partner is terrifically important for evaluations of femininity for women [36]. For some, attempts to secure and keep a partner while trying to accommodate their HIV status were a challenge, and many entered new relationships, but did not disclose their status to the new boyfriends. They described developing strategies to manage the risk of not transferring the virus (always using condoms), whilst also dealing with the possibility of being abandoned if HIV status was disclosed. Managing fertility demands and expectations for lasting romantic relationships as an HIV-positive person was commonly discussed by the women and created anxieties and stress. These were particularly difficult for those who did not disclose to partners, since in South Africa having a baby together commonly “bonds” a relationship, and babies are often demanded by men [44]. Whilst many women feared the consequences of being “found out” by a partner to whom they had not disclosed, a few interviews gave an inkling that non-disclosure was sometimes understood on both sides with a woman giving an account of how her new boyfriend protected her from gossip despite not having discussed HIV status with each other.

Similar non-disclosure with intimate partners was not reported by men although three of the four participants who did not disclose to anyone were young men from Mthatha – their motivation for no-disclosure was because they viewed disclosure to be risky and not of benefit to them in their current lifestyle. The maintenance of silence among HIV-positive adolescent was a key theme in a study of adolescents from developed countries where the silence was seen as part of managing stigma in the social world of adolescents [45].

Many of the women recognized that their partners might possibly be HIV positive as well. This they derived from their partners’ physical symptoms, their illness history (TB, shingles) or women made the deductions from their partners’ HIV risk profile such as their sexual reputation and the deaths and illness of their current or previous girlfriends. Few of these partners tested or were prepared to discuss the possibility of their own HIV infection, and this created many tensions such as those related to condom use. Male reluctance to acknowledge their illness was explained by one of the men “we actually try to … it's hard for a male to come out, to be open and comfortable because you are telling that you are suffering from other illness”. A young woman explained how her boyfriend revealed his status when she dumped him. He had previously claimed to have tested negative when she ask him to test. She said “When I dumped him he shouted at me and told me that I must not sleep around because he has got AIDS too”. For men, HIV-positive status was a sign of weakness and challenges their masculinity. Our data show that men (who were participants and from the accounts related from female participants) from both sites were desperate to protect their sense of manhood from being undermined by an HIV identity, and this fear shaped their behaviours in their intimate relations. This support what has been reported in the literature on masculinity [47].

Discussion

Stigma has been identified as one of the most poorly understood aspects of the HIV epidemic [16]. This study among HIV-positive people from two diverse settings has shown that although fear of HIV stigma was a part of most people's lives, it did not encompass or dominate their daily social interactions neither did it create major structural difficulties for living with HIV or disruption of their lives. Few participants in this study had personal experiences of discrimination, and the most harmful actions taken against them included insults and gossips which they could manage and deal with by opposing and resisting such labelling and this did not appear to have much impact on the quality of their lives. The stigma in the form of insults and gossips did not result in status loss for the participants, although this was the intention of the stigmatizer and this was the reason why participants could resist it successfully. Indeed for some participants the biggest obstacles in their lives were not HIV, but poverty and the daily problems of sexual relationships including intimate partner violence and managing (his and her) multiple partners, as are commonly described in the South African literature [46]. The study showed how the stigma experiences were shaped by the social world of the participants and intertwined within the normal daily life, where it was commonly used as an accessible tool during fights or ripe fodder for insults.

The study also showed that social contact promoted de-stigmatization which has also been reported in other South African studies [30,31,48] with the very real experiences of participants from Cape Town having many others with HIV in their immediate social networks which supported the perceptions of the commonness of the disease, assisted many with the development of resilience and psychosocial coping strategies such as managing and preventing stigma opportunities or mitigating its impact.

Disclosure had many dimensions to it, and it was shaped by perceived stigma responses. This study provides some insight into who discloses, and under which circumstances and what reactions are encountered. For many of the participants from Cape Town, decisions to disclose were motivated by the critical need to access to the ART program, and this might be the bias in the sample with participants from Mthatha most often not accessing healthcare as often. However, disclosure, although selective, was still a common occurrence among them and such active disclosure can be viewed as a form of resistance. Non-disclosure by the young men could have been due to internalized-stigma, but none of them displayed the anxiety, fear, low self-esteem or hopelessness that might have been expected if this had been the case, and it is more likely that their non-disclosure was a form of defence mechanism – protection against the consequences of and confronting an HIV status. More than one of the men said they did not want to be controlled by parents – thus referring to resistance to criticism and loss of independence. The research on HIV and masculinity has shown how men often resist diagnosis [47], and the abandonment of partners could have been related to not wanting to deal with a female partner's HIV status because it would force them to deal with the possibility of their own. Here men's struggle with an HIV+identity, with equated weakness or failure, was clearly rooted in the challenge HIV posed to their sense of masculine strength. An emerging body of research on HIV and masculinities has emerged in South Africa [39,49–51], and these findings will contribute and inform the development of interventions to promote positive adjustment to HIV status for men. Dunkle's et al.'s work in Soweto among HIV-positive men resonates strongly with the findings of our study [52]. In addition couple counselling and testing have potential for addressing men's identity fears, and many women in the study who had not disclosed their status to their partners because of limited opportunities to discuss HIV status recognized its value and had planned this as one of their strategies.

Gender has been used as an analytic tool to deepen the understanding of the HIV epidemic in general [37,53,54], and its links to HIV stigma fall within this. This study provides further evidence of how gossip and blaming are used to try to control women's sexuality, with the label “promiscuous” being deployed in social responses to their HIV status, in a way that is not done for men. Particularly in Mthatha, which is socially conservative, this generated feelings of shame, guilt and blame. The extracts illustrating gossip and the trade of insults during conflict demonstrated how women and not men were blamed in prevailing discourses for bringing HIV into relationships. Interestingly most women in both settings seldom spoke of having contested this blame.

The resistance to stigma was very commonly reported in this study and most often by women who seldom remained passive demonstrating their agency. The basis of their resistance was knowledge of human rights law and showed their attempts and determination not to internalize a negative HIV label. Agency was also demonstrated in many other diverse forms, such as public disclosures as well as attempts to resolve problems in intimate relationships. These included leaving abusive relationships and refusing to have sex without condoms. Although these were mainly from women in Cape Town, it does show how some women did not simply accept what happened to them. One of the major challenges for some women was to juggle between both their HIV status and search for intimacy and love relationships. Many sought and found new relationships and almost always without disclosing their HIV status. The dilemma of protecting the new partner from HIV (within the context of men not being keen to use condoms) and protecting themselves against future blame of deliberate infection remained a struggle for these women. Here, peer support was directed at encouraging the women to meet their own emotional goals rather than health concerns, as the support networks discouraged disclosure to new sexual partners and seemingly those who provided the advice did likewise. These findings highlight the importance of addressing gender and social norms where the “social” may be configured of others with HIV. Interventions for HIV-positive persons would be advised to be mindful of and to address this. Heterosexually transmitted HIV mostly arises from sexual intimacy in relationships and efforts to change sexual practices of those infected must build on best practice and not rely on “staying safe” prevention messaging. Although none of the men reported deliberate non-disclosure, women recognized that their male partner had often known their status, but had withheld this information. Hardly surprising on both accounts given that for both men and women with having partners is inseparably linked to ideas of successful manhood and womanhood [36,55].

Support for those who disclosed their positive status was surprising, and it is encouraging evidence of greater levels of acceptance of HIV which could be indicative of changing social values reported in other studies [30,56]. The support had different dimensions to it such as practical, social and emotional. Almost all in the study had enlisted family support, and nobody was rejected by close family members, although reactions from parents showed their continued perceptions of the disease as linked to stigma metaphors of HIV as associated with death, punishment, contagion, shame and guilt. Support from younger family members was not underpinned by the same stigma references. Most encouraging was the new friendships that were developed but this was however largely absent in the Mthatha group, where disclosure was viewed not as a beneficial among the young. The limited access to both formal and informal support networks for those living in the Eastern Cape is a reflection of the availability of health, socio-economic and infra-structure resources in this Province.

The resistance to stigma by HIV people themselves was also encouraging and showing how stigma was transformed into active resistance. The study also provides evidence that structural interventions such as policy support have an impact on stigma experiences with benefits clearly shown for the HIV-positive population. Many HIV stigma studies focus on the period immediately after diagnosis, but this study was performed among people who have known and lived with the disease for a while (at least for one year) and provides a perspective on how they adapted and continued their lives after an HIV diagnosis. Although much research on HIV stigma has emerged in the last few years with the earlier studies focusing on measuring the level of stigma or exploring feelings and beliefs of those not living with HIV, this study contributes to the growing number of studies using qualitative methods to explore experiences among positive people in South Africa [31,42,57,58], and these are critical for feeding into prevention interventions among positives.

The accounts of stigma and fear found in our study fits in very well with Deacons et al.'s [16] conceptual framework, as it allowed us to separate stigma from discrimination and the examination of how people reacted to the stigma which is important for determining its impact. The study showed that although stigma was still a part of people's lives, it did not dominate their social interactions and most resisted the stigma and sought to regain normality. The diversity of the HIV population and the gender nature of experiences must be considered when we intensify our stigma reduction efforts, and particular attention must be towards those that are not yet on the ARV programmes.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cape Town City Health Department and the staff of the ARV clinic. We thank Prof. D Mwesigwa-Kayongo from Walter Sisulu University (assistance and advice at the start of the study), Busiswa Mketo (fieldworker), Siphokazi Dada (fieldworker), Bongwekazi Rapiya (transcriber) and members of the Stepping Stones Mthatha Community Advisory Board. We also wish to thank our participants.

Competing interest

We, the authors, declare that we have no competing interest.

Authors' contributions

All authors have read and approved the final version. NA with assistance from RJ in the conceptualizing of the project. NA was primarily responsible for the writing of the research proposal as well as for the coordination of the study and with assistance of fieldworkers. She also did the some of the interviews. NA with assistance from RJ coded and analyzed the data and both NA and RJ wrote the manuscript.

Funding sources

The study was funded by the South African Department of Health and the South African Medical Research Council.

References

- 1.Herek GM, Capitanio JP. AIDS stigma and sexual prejudice. Am Behav Sci. 1999;42:1126–43. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maman S, Abler L, Parker L, Lane T, Chirowodza A, Ntogwisangu J, et al. A comparison of HIV stigma and discrimination in five international sites: the influence of care and treatment resources in high prevalence settings. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, Maman S, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, et al. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(12):2279–87. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parker B, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asante A. Scaling up HIV prevention: why routine or mandatory testing is not feasible for sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(8):644–6. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.037671. Epub 2007/09/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Logie C, Gadalla TM. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):742–53. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nachega JB, Morroni C, Zuniga JM, Sherer R, Beyrer C, Solomon S, et al. HIV-related stigma, isolation, discrimination, and serostatus disclosure: a global survey of 2035 HIV-infected adults. J Int Assoc Phys AIDS Care (Chic) 2012;11(3):172–8. doi: 10.1177/1545109712436723. Epub 2012/03/21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappin M, Wouters E, Booysen FL. Anxiety and depression amongst patients enrolled in a public sector antiretroviral treatment programme in South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):244. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-244. Epub 2012/03/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peltzer K, Ramlagan S. Perceived stigma among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: a prospective study in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23(1):60–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498864. Epub 2011/01/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coetzee B, Kagee A, Vermeulen N. Structural barriers to adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a resource-constrained setting: the perspectives of health care providers. AIDS Care. 2011;23(2):146–51. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.498874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. In: Goffman E, editor. New Jersey: Penguin Books; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herek GM. AIDS and stigma: a conceptual framework and research agenda. AIDS Public Policy. 2004;13(1):36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, Stewart A, Phetlhu R, Dlamini PS, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(6):541–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deacon H, Stephney I, Prosalendis S. Understanding HIV/AIDS stigma: a theoretical and methodological analysis. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castro A, Farmer P. Understanding and addressing AIDS-related stigma: from anthropological theory to clinical practice in Haiti. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):53–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.028563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deacon H. Towards a sustainable theory of health-related stigma: lessons from the HIV/AIDS literature. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;16(6):418–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earnshaw V, Chaudoir S. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1160–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prior L, Wood F, Lewis G, Pill R. Stigma revisited, disclosure of emotional problems in primary care consultations in Wales. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(10):2191–200. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein J. HIV/AIDS stigma: the latest dirty secret. Afr J AIDS Res. 2003;2(2):95–101. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2003.9626564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simbayi LC, Kalichman S, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Internalized stigma, discrimination, and depression among men and women living with HIV/AIDS in Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(9):1823–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maughan-Brown B. Stigma rises despite antiretroviral roll-out: a longitudinal analysis in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Parker W, Zuma K, Bhana A, et al. South African National HIV prevalence, HIV incidence, behaviour and communication survey. Cape Town: HSRC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorsdahl KR, Mall S, Stein DJ, Joska JA. The prevalence and predictors of stigma amongst people living with HIV/AIDS in the Western Province. AIDS Care. 2011;23(6):680–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.525621. Epub 2011/03/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh D, Chaudoir SR, Escobar MC, Kalichman S. Stigma, burden, social support, and willingness to care among caregivers of PLWHA in home-based care in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2011;23(7):839–45. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542122. Epub 2011/03/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogunmefun C, Gilbert L, Schatz E. Older female caregivers and HIV/AIDS-related secondary stigma in rural South Africa. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2011;26(1):85–102. doi: 10.1007/s10823-010-9129-3. Epub 2010/10/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demmer C. Experiences of families caring for an HIV-infected child in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: an exploratory study. AIDS Care. 2011;23(7):873–9. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.542123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daftary A. HIV and tuberculosis: the construction and management of double stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1512–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.027. Epub 2012/03/27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilbert L, Walker L. “They (ARVs) are my life, without them I'm nothing” – experiences of patients attending a HIV/AIDS clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health Place. 2009;15(4):1123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goudge J, Ngoma B, Manderson L, Schneider H. Stigma, identity and resistance among people living with HIV in South Africa. SAHARA J. 2009;6(3):94–104. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hasan MT, Nath SR, Khan NS, Akram O, Gomes TM, Rashid SF. Internalized HIV/AIDS-related stigma in a sample of HIV-positive people in Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2012;30(1):22–30. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v30i1.11272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day C, Monticelli F, Barron P, Haynes R, Smith J, Sello E. District health barometer 2008/9. Durban: Health System Trust; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Khuzwayo N, et al. A cluster randomized-controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of Stepping Stones in preventing HIV infections and promoting safer sexual behaviour amongst youth in the rural Eastern Cape, South Africa: trial design, methods and baseline findings. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11(1):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01530.x. Epub 2006/01/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods for analysing talk, text & interaction. London: Sage Publications Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Sexuality and the limits of agency among South African teenage women: theorising femininities and their connections to HIV risk practises. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Jun;74(11):1729–37. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.020. Epub 2011 May 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(6) doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-6. Epub 2010/02/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poindexter CC. The lion at the gate: an HIV-affected caregiver resists stigma. Health Soc Work. 2005;30(1):64–74. doi: 10.1093/hsw/30.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch I, Brouard PW, Visser MJ. Constructions of masculinity among a group of South African men living with HIV/AIDS: reflections on resistance and change. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12(1):15–27. doi: 10.1080/13691050903082461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyrod R. Masculinity and the persistence of AIDS stigma. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(4):443–56. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.542565. Epub 2011/01/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrell R, Jewkes R. Carework and caring: a path to gender equitable practices among men in South Africa? Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-17. Epub 2011/05/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilbert L, Walker L. ‘My biggest fear was that people would reject me once they knew my status …': stigma as experienced by patients in an HIV/AIDS clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Health Soc Care Commun. 2010;18(2):139–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paruk Z, Petersen I, Bhana A, Bell C, McKay M. Containment and contagion: how to strengthen families to support youth HIV prevention in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2005;4(1):57–63. doi: 10.2989/16085900509490342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dyer SJ, Abrahams N, Mokoena NE, Van der Spuy ZM. “You are a man because you have children": experiences, reproductive health knowledge and treatment-seeking behaviour among men suffering from couple fertility. Hum Reprod. 2004;17(16):1663–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fielden SJ, Chapman GE, Cadell S. Managing stigma in adolescent HIV: silence, secrets and sanctioned spaces. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(3):267–81. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.525665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jewkes R, Morrell R. Gender and sexuality: emerging perspectives from the heterosexual epidemic in South Africa and implications for HIV risk and prevention. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morrell R, Jewkes R, Lindegger G. Hegemonic masculinity/masculinities in South Africa. Men Masculinities. 2012;15(1):11–30. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Campbell C, Deacon H. Unravelling the contexts of stigma: from internalisation to resistance to change. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;16(6):411–17. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morrell R, Jewkes R. Carework and caring: a path to gender equitable practices among men in South Africa? Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colvin CJ, Robins S, Leavens J. Grounding ‘Responsibilisation Talk’: masculinities, citizenship and HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. J Dev Stud. 2010;46(7):1179–95. doi: 10.1080/00220388.2010.487093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Townsend L, Jewkes R, Mathews C, Johnston LG, Flisher AJ, Zembe Y, et al. HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011 Jan;15(1):132–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dunkle K, Diedricht J. “Now you are no more a man”: living with HIV as a challenge to hegemonic masculinity in South Africa. IASSCS (International Association for the Study of Sexuality, Culture and Society) VII Conference: Contested Innocence – Sexual Agency in Public and Private Space; 2009; Honoi, Vietnam. 2009. Apr 15–18, [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greig A, Peacock D, Jewkes R, Msimang S. Gender and AIDS: time to act. AIDS. 2008;22(Suppl 2):S35–43. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327435.28538.18. Epub 2008/07/25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Jama PN, Puren A. Associations between childhood adversity and depression, substance abuse and HIV and HSV2 incident infections in rural South African youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(11):833–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.05.002. Epub 2010/10/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wood K, Jewkes R. ‘Dangerous love’ Love: reflections on violence in sexual relationships of young people in Umtata. In: Morell R, editor. Changing men in South Africa. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press; 2001. pp. 317–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zuch M, Lurie M. ‘A virus and nothing else': the effect of ART on HIV-related stigma in rural South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):564–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0089-6. Epub 2011/11/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosegood V, Preston-Whyte E, Busza J, Moitse S, Timaeus IM. Revealing the full extent of households' experiences of HIV and AIDS in rural South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(6):1249–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mills EA. From the physical self to the social body: expressions and effects of HIV-related stigma in South Africa. J Commun Appl Soc Psychol. 2006;16(6):498–503. [Google Scholar]