Abstract

The process of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is mediated by karyopherins. Dysregulated expression of karyopherins may trigger oncogenesis through aberrant distribution of cargo proteins. Karyopherin subunit alpha-2 (KPNA2) was previously identified as a potential biomarker for nonsmall cell lung cancer by integration of the cancer cell secretome and tissue transcriptome data sets. Knockdown of KPNA2 suppressed the proliferation and migration abilities of lung cancer cells. However, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying KPNA2 activity in cancer remain to be established. In the current study, we applied gene knockdown, subcellular fractionation, and stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture-based quantitative proteomic strategies to systematically analyze the KPNA2-regulating protein profiles in an adenocarcinoma cell line. Interaction network analysis revealed that several KPNA2-regulating proteins are involved in the cell cycle, DNA metabolic process, cellular component movements and cell migration. Importantly, E2F1 was identified as a potential novel cargo of KPNA2 in the nuclear proteome. The mRNA levels of potential effectors of E2F1 measured using quantitative PCR indicated that E2F1 is one of the “master molecule” responses to KPNA2 knockdown. Immunofluorescence staining and immunoprecipitation assays disclosed co-localization and association between E2F1 and KPNA2. An in vitro protein binding assay further demonstrated that E2F1 interacts directly with KPNA2. Moreover, knockdown of KPNA2 led to subcellular redistribution of E2F1 in lung cancer cells. Our results collectively demonstrate the utility of quantitative proteomic approaches and provide a fundamental platform to further explore the biological roles of KPNA2 in nonsmall cell lung cancer.

Transportation of proteins and RNAs into (import) and out of (export) the nucleus occurs through the nuclear pore complex and is a vital event in eukaryotic cells. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the large complex (>40 kDa) is mediated by an evolutionarily conserved family of transport factors, designated karyopherins (1). The family of karyopherins, including importins and exportins, share limited sequence identity (15–25%) but adopt similar conformations. In human cells, at least 22 importin β and 6 importin α proteins have been identified to date (2, 3). Karyopherins cannot be classified solely based on their cargo repertoires, because many of these proteins are targeted by several different members of the karyopherin family (4–6). The most well-established mechanism of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is the classical nuclear import pathway in which classical nuclear localization signal (cNLS)1-containing cargo proteins transported into the nucleus are recognized by importin α/importin β heterodimers (7). All importin β family members contain an N-terminal Ran-GTP-binding motif and selectively bind nucleoporins of the nuclear pore complex, whereas unusually, importin β interacts indirectly with hundreds of different cNLS-containing proteins via an adaptor protein, importin α. Importin α also acts independently through direct binding to cargo proteins without the requirement for importin β (8). The import and export processes of nucleocytoplasmic shuttle proteins are complicated, and dysregulated expression of karyopherin may have oncogenic effects resulting from the unusual distribution of cargo proteins. For example, aberrant nucleocytoplasmic localization of tumor suppressor proteins, such as PTEN, WT1, Arf, and p53, is involved in the development of several human cancers (9–14).

Karyopherin subunit alpha-2 (KPNA2) belongs to the karyopherin family and delivers numerous cargo proteins to the nucleus, followed by translocation back to cytoplasmic compartments in a Ran-GTP-dependent manner (15). One proposed hypothesis is that KPNA2 plays opposing roles in oncogenesis through modulation of proper subcellular localization of particular cargo proteins (16). For example, KPNA2 mediates the nuclear transport of NBN (also known as NBS1 or Nibrin), a component of the MRE11/RAD50/NBN (MRN) complex involved in double-strand break (DSB) repair, DNA recombination, cell cycle checkpoint control, and maintenance of DNA integrity and genomic stability. Nuclear NBN generally acts as a tumor suppressor protein (17–20). Inhibition or blockage of the interactions between KPNA2 and NBN results in reduction of DSB repair, cell cycle checkpoint signaling and radiation-induced nuclear focus accumulation (21), signifying inhibition of the tumor suppressor function of nuclear NBN, as it loses interactions with KPNA2. In addition, a recent study showed that cytoplasmic NBN plays an oncogenic role via binding and activation of the PI3-kinase/AKT pathway and promotes tumorigenesis (22). Therefore, KPNA2 appears to be a major determinant of the subcellular localization and the biological functions of its cargo proteins, such as NBN.

We previously identified and validated KPNA2 as a potential biomarker for nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by integration of cancer cell secretome and tissue transcriptome data sets (23). We detected KPNA2 overexpression in lung cancer tissues and showed that cancer cells with poor differentiation and high mitosis are independent determinants for nuclear KPNA2 expression in NSCLC. Data obtained from exogenous expression and KPNA2 knockdown experiments supported its involvement in cellular growth and motility of lung cancer cells. KPNA2 is also overexpressed in several cancer tissues, including breast cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, bladder cancer, and prostate cancer, and may be associated with tumor invasiveness (24–28). Moreover, KPNA2 is possibly involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, DNA repair, and migration (16, 23, 29–31). However, the molecular pathways regulated by KPNA2 in lung cancer are yet to be elucidated. Here, we applied stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based quantitative proteomic technology (32), in combination with gene knockdown and subcellular fractionation, to analyze KPNA2 siRNA-induced differentially expressed protein profiles in an adenocarcinoma cell line and explored the molecular mechanisms of KPNA2-mediated regulation in lung cancer.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture

The CL1-5 human lung cancer cell line was derived from one man with poorly differentiated lung adenocarcinoma and kindly provided by Professor P.C. Yang (Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan). Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum plus antibiotics at 37 °C at a humidified atmosphere of 95% air/5% CO2 (33). For SILAC experiments, CL1-5 cells were maintained in lysine-depleted RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 0.1 mg/ml heavy [U-13C6]l-lysine (Invitrogen) or 0.1 mg/ml light l-lysine (Invitrogen). Every 3–4 days, cells were split and media replaced with the corresponding light or heavy labeling medium. In approximately six doubling times, cells achieved almost 100% incorporation of isotopic labeling amino acids and were subjected to small interfering RNA treatments.

Gene Knockdown of KPNA2 With Small Interfering RNA

Gene knockdown of KPNA2 was performed as described previously (23). Briefly, 19-nucleotide RNA duplexes for targeting human KPNA2 were synthesized and annealed by Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, CO). In brief, CL1-5 cells cultured in stable isotope labeling medium were transfected with control siRNA (Heavy) and KPNA2 pooled siRNA (Light) (GAAAUGAGGCGUCGCAGAA, GAAGCUACGUGGACAAUGU, AAUCUUACCUGGACACUUU, GUAAAUUGGUCUGUUGAUG)), respectively using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagents (Invitrogen) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. At 48 h after transfection, cell lysates were prepared for Western blotting to determine gene knockdown efficacy.

Subcellular Fractionation

CL1-5 cells transfected with control siRNA or KPNA2 siRNA were mixed at an equal ratio (1:1) and subjected to a subcellular fractionation using the ProteoJETTM Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Protein Extraction Kit K0311 (Fermentas, Canada), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The efficacy of fractionation was determined via Western blotting using GAPDH as the cytosolic control and Lamin B as the nuclear control protein.

In-solution Digestion of Proteins and Micro-column Desalting

In-solution digestion was performed with the protocols described below. Briefly, the protein mixture (100 μg) was dissolved in 50 mm NH4HCO3, reduced with 10 mm dithiothreitol (DTT) for 30 min at 56 °C and alkylated using 30 mm iodoacetamide in the dark for 45 min at room temperature. Next, 30 mm DTT was added to quench iodoacetamide for 30 min at room temperature. The solution was diluted fivefold with 25 mm NH4HCO3, and trypsin added at a ratio of 1:50 and digested at 37 °C overnight. Micro-columns packed with SOURCE 15RPC (30 μl bed volume) were regenerated with series of steps: 100% acetonitrile (ACN)/0.1% formic acid (FA), 80% ACN/0.1%FA, 50% ACN/0.1% FA, and final equilibration with 0.1%FA. Samples were acidified with 0.1% FA and desalted using the micro-column via brief centrifugation at 3000 rpm at room temperature for 2 min. Peptides bound to resin were eluted using 25% ACN/0.1%FA, 50% ACN/0.1%FA and 80% ACN/0.1%FA (three bed volumes each).

Online Strong Ion Exchange/Reverse Phase Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry

Peptides prepared from in-solution digestion were separated and analyzed via the online two-dimensional liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (2D LC-MS/MS) technique using a strong cation exchange (SCX) and reverse-phase 18 (RP18) nanoscale liquid chromatography system coupled with a LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher, San Jose, CA) (34). Briefly, equal mixtures of SILAC peptides were injected into an in-house packed SCX column (Luna SCX, 5 μm, 0.5 × 150 mm, Phenomenex) and fractionated into 30 fractions using a 45 h continuous ammonium chloride gradient in the presence of 30% ACN and 0.1% FA. Each effluent of SCX fraction (1 μl/min) was continuously mixed with a stream of 0.1% FA/H2O (50 μl/min), and peptides were trapped on a RP column (Source 15 RPC, 0.5 × 5 mm, GE Healthcare) and separated using coupled BEH C18 chromatography (1.7 μm, 0.1 × 120 mm, Waters) with an acetonitrile gradient in 0.1% FA performed on a Dionex UltiMate 3000 nano LC system. MS/MS analysis was performed on a LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometer with a nanoelectrospray ion source (Proxeon Biosystems). Full-scan MS spectra (m/z 430–m/z 2000) were acquired in the Orbitrap mass analyzer at a resolution of 60,000 at m/z 400. The lock mass calibration feature was enabled to improve mass accuracy. The most intense ions (up to 12) with a minimal signal intensity of 20,000 were sequentially isolated for MS/MS fragmentation in the order of intensity of precursor peaks in the linear ion trap using collision-induced dissociation energy of 35%, Q activation at 0.25, activation time of 30 ms, and isolation width of 2.0. Targeted ions with m/z ± 30 ppm were selected for MS/MS once and dynamically excluded for 50s.

Database Search and Protein Quantification Pipeline

All MS and MS/MS data were analyzed and processed with Quant.exe in the MaxQuant environment (version 1. 0. 13. 8), developed by Professor M. Mann for peptide identification and quantification analyses (35). The top six of fragment ions per 100 Da of each MS/MS spectrum were extracted for a protein database search using the Mascot search engine (version 2.2.03, Matrix Science) against the concatenated Swiss-Prot v.56 human forward and reverse protein sequence data set with a set of common contaminant proteins (total 45500 entries). The search parameters were set as follows: carbamidomethylation (C) as the fixed modification, oxidation (M), N-acetyl (protein), and pyro-Glu/Gln (N-term) as variable modifications, 5 ppm for MS tolerance, 0.5 Da for MS/MS tolerance, and 2 for missing cleavage. The SILAC label (K) was set as either none, fixed or variable modifications, depending on whether the precursor ion was determined as light, heavy or uncertain label by the MS feature detection algorithm of MaxQuant, respectively, to generate three Mascot search results. The peptides and proteins identified in all search results were further analyzed with Identity.exe using following criteria: six for minimum peptide length, one for minimum unique peptides for the assigned protein. The posterior error probability of peptides identified in forward and reverse databases was used to rank and determine the false discovery rate (FDR) for statistical evaluation (35, 36). First, peptide and protein identifications with FDR less than 1% were accepted. The peptides shared (not unique for leading proteins) between multiple leading proteins were assigned to one of them (the first one) as razor peptides. And then, proteins with at least two ratio counts generated from unique and razor peptides were considered as quantified proteins for further analysis (detailed information is summarized in supplemental Tables S3 and S4). The median value of SILAC ratios was calculated as protein abundance (KPNA2 siRNA/control siRNA ratio) to minimize the effects of outlier values. Finally, global median normalization was applied for recalculating protein abundance (normalized protein ratio) to reduce the system error from sample preparation in each experiment.

Network Analysis

After quantification analysis, differentially expressed proteins of interest were converted into gene symbols and uploaded into MetaCore Version 6.5 build 27009 (GeneGo, St. Joseph, MI) for biological network building. MetaCore consists of curated protein interaction networks based on manually annotated and regularly updated databases. The databases describe millions of relationships between proteins based on publications on proteins and small molecules. These relationships include direct protein interactions, transcriptional regulation, binding, enzyme-substrate interactions, and other structural or functional relationships. In the present study, we used a variant of the shortest paths algorithm in Analyze Networks to map the hypothetical networks of uploaded proteins by default settings. The relevant network maps are analyzed based on relative enrichment of the uploaded proteins and also relative saturation of networks with canonical pathways. In this workflow the networks are prioritized based on the number of fragments of canonical pathways on the networks.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from control siRNA and KPNA2 siRNA-transfected CL1-5 cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized via reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with the SuperscriptIIIkit (Invitrogen). Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 750 nm forward and reverse primers, varying amounts of template and 1× Power SYBR Green reaction mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The primers used in this study were designed using Primer Express Software (Applied Biosystems) and the sequences listed in supplemental Table S1. SYBR Green fluorescence intensity was determined using the ABI PRISM 7500 detection system (Applied Biosystems), and the gene level normalized against that of the beta-actin control gene.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cells transfected with control siRNA or KPNA2 siRNA for 48 h were harvested by trypsinization. For cell cycle analysis, cells were fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol comprising 2 mg/ml RNase for 30 min, and ultimately stained with propidium iodide (PI, 50 mg/ml) for 10 min. The fluorescence of PI in control siRNA or KPNA2 siRNA-transfected cells was determined using flow cytometric analysis (BectonDickinson FACScan SYSTEM, Mountain View, CA). We counted the percentage of cells in the sub-G0/G1, G0/G1, S and G2/M phases using CellQuestTM programs.

Plasmid Construction

For expression of E2F1 in mammalian and E. coli cells, the open reading frame of E2F1 was obtained from CL1-5 cells by PCR using the sense primer, 5′-GAATTCAACATGGCCTTGGCCGG-3′, and antisense primer, 5′-TCTAGAGAAATCCAGGGGGGTGA-3′. The full-length E2F1 gene fragment was ligated into pGEM-T easy vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) designed to introduce an EcoRI site at the initiating methionine and an XbaI site six base pairs downstream of the C terminus of E2F1, and subsequently subcloned into the eukaryotic expression vector, pcDNA 3.1/myc-His (Invitrogen). To generate recombinant E2F1 from E. coli, the gene fragment was subcloned into the prokaryotic expression vector, pET-15b (Novagen Darmstadt, Germany), and transformed into the BL-21 cell line to produce His-tagged E2F1 protein. To map the binding domains between KPNA2 and E2F1, domain structure analysis (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P52292) was applied to predict potential NLS binding sites in KPNA2, and cNLS Mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi) was applied to predict potential cNLS sites in E2F1. Based on domain structure analysis (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P52292), two regions, 142W-R238 and 315R-N403 were predicted as potential NLS binding sites in KPNA2. Serious deletion constructs of KPNA2 with or without these two NLS binding sites (KPNA2-D1∼D4 fragments in Fig. 5C) were subcloned into pGEX4T (GE Healthcare) for producing recombinant proteins in E. coli. Based on the cNLS Mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi), two potential cNLS sites were predicted in E2F1, 85RPPVKRRLDLE95 and 161KVQKRRIYDI170 (Fig. 5D). The deletion and site-directed mutagenesis of the cNLS sequences in E2F1 were performed using the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), according to manufacturer's instructions. Mutated products were verified using direct DNA sequencing. The primer sequences used for these constructions were summarized in supplemental Table S2.

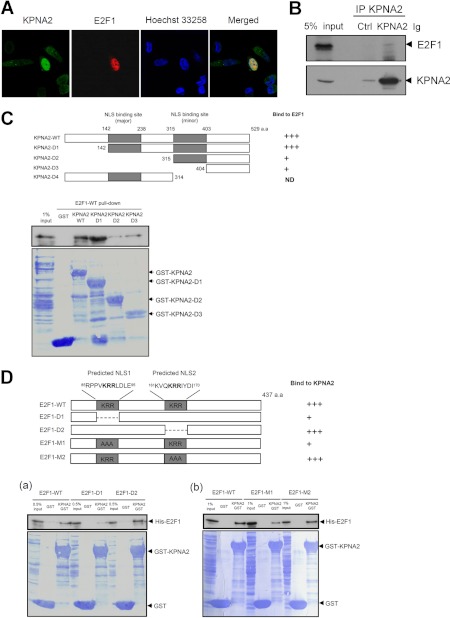

Fig. 5.

KPNA2 interacts with E2F1, both in vitro and in vivo. A, E2F1 was co-localized with KPNA2. CL1-5 cells were cotransfected with KPNA2 and E2F1 plasmids. After transfection for 48 h, cells were prepared for immunofluorescence staining using anti-KPNA2 and anti-myc antibodies to detect the exogenous expression of KPNA2 and E2F1, respectively. B, E2F1 was co-immunoprecipitated with KPNA2. CL1-5 cells were lysed and the resulting cell lysates were analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-KPNA2 IgG or control IgG coupled with protein G agarose beads. Details are provided under “Experimental Procedures.” After an overnight incubation at 4 °C, the precipitated protein complexes were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-E2F1 and anti-KPNA2 antibodies as indicated. C, In vitro binding assay of serial truncated KPNA2 and E2F1. His-tagged E2F1 was generated from E. coli, and the soluble fractions of cell lysates incubated with 10 μg GST and four serial truncated genes of GST-KPNA2 (KPNA2 WT and KPNA2 D1∼D3)-immobilized glutathione-Sepharose beads, respectively. Bound proteins were detected by Western blotting, and Coomassie brilliant blue staining indicated equal amounts of GST and GST-KPNA2 proteins used in the pull-down assay. The diagram represents the NLS binding sites of KPNA2 and serial truncated clones. ND, not determined. D, In vitro binding assay of KPNA2 and mutated E2F1. His-tagged E2F1 D1 and D2 (a), M1 and M2 (b) were generated from E. coli, and the soluble fractions of cell lysates incubated with 10 μg GST and GST-KPNA2-immobilized glutathione-Sepharose beads, respectively. Bound proteins were detected by Western blotting, and Coomassie brilliant blue staining indicated equal amounts of GST and GST-KPNA2 proteins used in the pull-down assay. The diagram represents the predicted NLS sequences of E2F1 and NLS mutation clones.

Immunofluorescence Assay

Transfected cells were cultured in glass coverslips using the 12-well culture dish format. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and treated with permeabilized buffer (0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.05% SDS in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)). Next, cells were blocked in blocking solution (0.1% saponin, 0.2% bovine serum albumin in PBS) and incubated with primary antibodies. After washing, cells were further incubated with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated or Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and DNA was stained with Hoechst 33258. Following a second wash with PBS, cells were mounted in 90% glycerol in PBS containing 1 mg/ml of ρ-phenylenediamine and observed under a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany).

In Vitro Binding Assay of E2F1 and KPNA2

Recombinant GST and GST-KPNA2 prepared from soluble fractions of E. coli lysates were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C overnight. GST and GST-KPNA2 proteins (10 μg) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads were incubated with 1000 μl soluble fraction of His-tagged E2F1, including wild-type and NLS mutant proteins, respectively. After washing three times with ice-cold PBS, bound proteins were boiled for 10 min with SDS sample buffer and subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting assay.

Co-immunoprecipitation Assay

CL1-5 cells were extracted in Nonidet P-40 (Nonidet P-40) lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mm Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm Na3VO4, 5 mm EDTA pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and fractionated by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 15 min at 4 °C) to obtain cell lysates. For co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous KPNA2 with p53, c-Myc or E2F1, cell lysates (2 mg protein) from CL1-5 cells were incubated with 3 μg of anti-KPNA2 antibody (B-9, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) or control IgG together with 50 μl of a 50% (w/v) slurry of protein G beads. All the incubations were rotated overnight at 4 °C, and then washed two times with Tris buffer A (20 mm Tris-HCl ph 7.5, 250 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm DTT) and four times with Tris buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl ph 7.5, 0.5 mm DTT). The resulting protein complexes were eluted with SDS sample buffer, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and analyzed by Western blotting using primary antibodies raised against the following proteins: p53 (DO1, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), E2F1(KH95, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), c-Myc (9E10, Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, CA) and KPNA2 (Proteintech Group Inc.). Subsequently, membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibodies and the signals were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence according to the specifications from the supplier (Millipore).

RESULTS

Identification and Quantification of Differentially Expressed Proteins in KPNA2 Knockdown Cells with the SILAC Proteomic Approach

To investigate the molecular mechanisms of KPNA2-mediated regulation in lung cancer cells, we applied the SILAC-based quantitative proteomic method combined with subcellular fractionation to systematically analyze KPNA2 siRNA-induced differential expression protein profiles in the CL1-5 adenocarcinoma cell line. A schematic diagram of the experimental workflow is shown in Fig. 1A. Briefly, CL1-5 cells were cultured in light or heavy labeling media, followed by transfection with control siRNA and KPNA2 siRNA, respectively. Equal numbers of siRNA-transfected cells were mixed and analyzed using 2D LC-MS/MS to allow quantitative analysis of the whole proteome. Simultaneously, quantitative analysis of the nuclear proteome was performed using protein fractionation, followed by 2D LC-MS/MS analysis. Western blotting analysis revealed the efficiency of KPNA2 knockdown and nuclear fractionation (Fig. 1B) in lung cancer cells with SILAC labeling. Following the experimental workflow, a total of 5770 and 4385 nonredundant proteins in the whole and nuclear proteomes were identified, respectively. Among these proteins, 2975 and 2353 proteins with at least two ratio counts generated from unique and razor peptides in the whole and nuclear proteomes were quantified, respectively. The ratio distributions of quantified proteins are presented in Fig. 1C. Details of the quantified proteins and peptides are shown in supplemental Table S3 and Table S4. The annotated spectra represented quantified proteins with single peptide identifications, including 136 proteins identified in whole proteome and 137 proteins identified in nuclear proteome were shown in supplemental Fig. S1. Using 2-fold change as the criterion for selection of KPNA2-regulated proteins from the whole proteome, we identified 62 up-regulated and 47 down-regulated proteins in KPNA2 siRNA-transfected cells, compared with control cells (supplemental Table S5). To confirm that quantitative information obtained from MS-based proteomic analysis reflects the protein expression levels in vivo, we assessed the expression levels of 3 (CLNS1A, PLAU and SEPT9) of the 109 differentially expressed proteins using Western blotting. The consistency between Western blotting and MS-based quantitative results, depicted in Fig. 2A, supports the theory that the SILAC strategy represents a reliable and feasible method to analyze KPNA2 siRNA-induced differentially expressed protein profiles. In addition, we verified 14 differentially expressed proteins (including 10 up-regulated and 4 down-regulated) using qPCR analysis, with a view to determining the mRNA levels in KPNA2 knockdown cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, KPNA4, PLAU, and SEPT9 mRNA levels were decreased (KPNA2 siRNA/control siRNA ratio: 0.43, 0.17, and 0.64) and those of CBS, CLNS1A, GALNT7, HMGCS1, PKP3, RBL1, and TLE3 were increased (KPNA2 siRNA/control siRNA ratio: 1.20, 2.01, 1.76, 2.49, 1.78, 5.87, and 1.24) in KPNA2 knockdown cells, compared with control cells, in which mRNA fold changes were positively correlated to the SILAC quantitative ratio. However, the mRNA levels of ALDH1A3, DDX11, FLG, and PELP1 were similar (KPNA2 siRNA/control siRNA ratio: 1.02, 1.00, 1.00, and 1.07) between the two cell populations. These results collectively suggest that qPCR analysis is an effective alternative strategy to narrow down the range of differentially expressed candidates obtained from MS-based quantitative analysis in a high-throughput manner in cases where the antibody is not available.

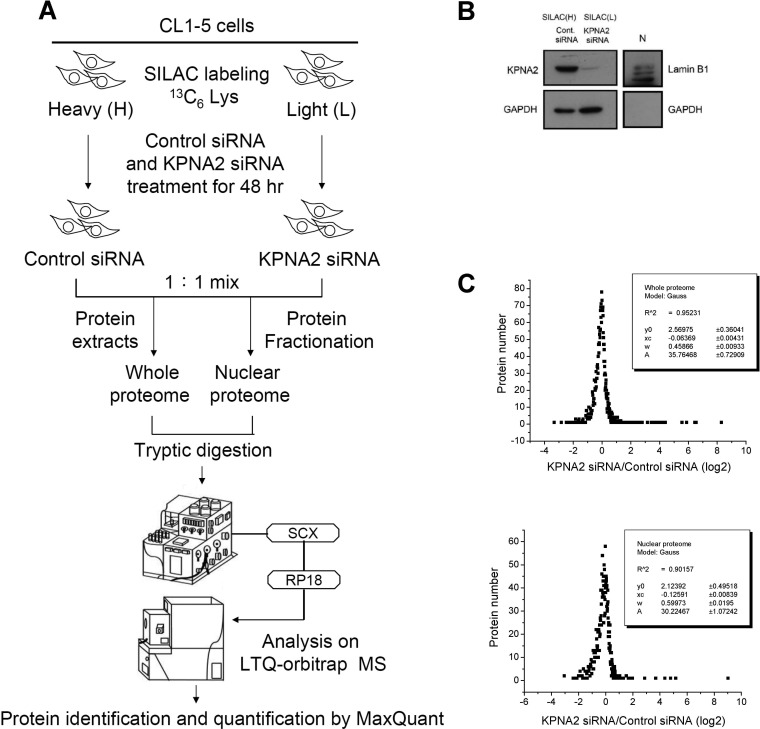

Fig. 1.

Strategy used to analyze KPNA2 siRNA-induced differentially expressed protein profiles in lung cancer cells. A, Schematic diagrams show the workflow designed for profiling KPNA2-regulated proteins via proteomic-based analysis. The processes include SILAC labeling, siRNA treatments, subcellular fractionation, 2D LC-MS/MS analysis, protein identification and quantification with MaxQuant software. B, CL1-5 cells were cultured in SILAC-labeling media and transfected with control and KPNA2 siRNA, respectively. After transfection for 48 h, equal numbers of heavy- and light-labeled cells were mixed and subjected to nuclear fractionation, as described in Materials and Methods. Total cell lysates (20 μg per lane) and nuclear fractions (N, 10 μg per lane) from siRNA-transfected cells were analyzed by Western blotting to examine the efficiency of gene knockdown. GAPDH was used as a cytosolic control and lamin B1 as a nuclear control. C, The log2 ratio distributions of quantified proteins were fitted with a Gaussian function using Origin 6.0 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA). Mean (xc) and two standard deviation (w) values were calculated using the formula: y = y0 + (A/[rad]πW2/2)e[/rad](–2((x − xc)/w)2).

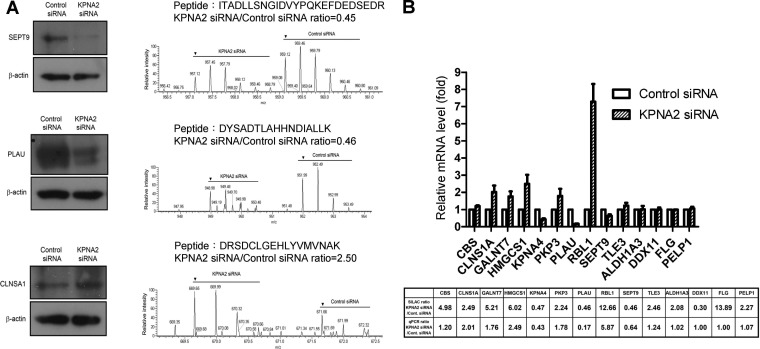

Fig. 2.

Validation of KPNA2-regulated proteins. A, CL1-5 cells were transfected with control and KPNA2 siRNA, respectively. After transfection for 48 h, cell lysates were prepared (20 μg per lane) and detected using Western blotting. The MS spectra, peptide sequences, and quantified ratios (arrow indicates the first peak of the spectrum) of SET9, PLAU and CLNSA1 are presented. B, The relative mRNA levels of differentially expressed proteins in KPNA2 knockdown cells. Total RNA from control siRNA or KPNA2 siRNA-transfected cells was purified and reverse-transcribed, and the resultant cDNA subjected to qPCR analysis using gene-specific primers. Fold change of the mRNA level for each protein in KPNA2 knockdown cells was calculated as a ratio relative to control siRNA-treated cells. Results were expressed as mean values ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Network Analysis of KPNA2-regulated Signaling Based on Quantitative Whole Proteome Analysis

To clarify the potential pathways or processes involving KPNA2, the 109 proteins displaying a twofold change in whole proteome analysis (supplemental Table S5) were further examined using the MetaCore bioinformatics tool. This analysis revealed that the differentially expressed proteins are highly correlated with organ development, anatomical structure morphogenesis, cellular component movement, cell proliferation, migration and locomotion (Table I). The process listed in the second significant network was most consistent with our previous finding that knockdown of KPNA2 reduces proliferation and migration in lung cancer cells (23). Notably, 13 proteins in the second significant network (CSTA, CDC45L, FN1, FOSL1, JUP, PKP3, PLAU, RBL1, SEPT9, SFN, S100A7, and UHRF1) are reported to be dysregulated, whereas the other 13 proteins (ALDH1A3, ARPP19, CBS, CLNS1A, DDX11, FLG, GALNT7, HMGCS1, KPNA4, PELP1, PNPLA6, RRM2, and TLE3) are not dysregulated in lung cancer (Table II) (37–52). Therefore, the quantitative whole proteome data set may facilitate our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of KPNA2 in lung cancer tumorigenesis and provide a resource for biomarker discovery in human cancers.

Table I. Top three significant biological networks in which 109 differently expressed proteins identified in the whole proteome are involved.

| No | GO processes | Total nodes | Root nodes | Pathway | p-Value | z-Score | g-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Organ development (64.2%), anatomical structure morphogenesis (55.2%), positive regulation of cell migration (26.9%), positive regulation of cellular component movement (26.9%), positive regulation of locomotion (26.9%) | 74 | 19 | 140 | 9.32E-36 | 50.01 | 225.01 |

| 2 | Regulation of cell proliferation (45.5%), anatomical structure morphogenesis (50.0%), positive regulation of cell migration (24.2%;), organ development (57.6%), positive regulation of cellular component movement (24.2%) | 73 | 26 | 79 | 3.6E-53 | 69.07 | 167.82 |

| 3 | Anatomical structure morphogenesis (60.0%; 5.206e-26), organ development (67.7%; 6.210e-25), positive regulation of cell migration (30.8%; 7.832e-25), positive regulation of cellular component movement (30.8%; 2.865e-24), positive regulation of locomotion (30.8%; 3.133e-24) | 72 | 18 | 92 | 1.1E-33 | 48.05 | 163.05 |

Table II. Twenty-six differentially expressed proteins in the second significant network deduced from whole proteome analysis.

| Symbol | Recommended name | Protein ratio obtained from whole proteome (KPNA2 siRNA/ control siRNA) | mRNA ratio obtained from qPCR (KPNA2 siRNA/ control siRNA) | Unique peptide number | Dysregulated in lung cancer (reference number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBS | Cystathionine beta-synthase | 4.98 | 1.20 | 4 | No |

| CLNS1A | Methylosome subunit pICln | 2.49 | 2.01 | 7 | No |

| GALNT7 | N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 7 | 5.21 | 1.76 | 3 | No |

| HMGCS1 | Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase, cytoplasmic | 6.02 | 2.49 | 15 | No |

| KPNA4 | Importin subunit alpha-4 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 7 | No |

| PKP3 | Plakophilin-3 | 2.24 | 1.78 | 4 | Yes (37) |

| PLAU | Urokinase-type plasminogen activator | 0.46 | 0.17 | 2 | Yes (38) |

| RBL1 | Retinoblastoma-like protein 1 | 12.66 | 5.87 | 2 | Yes (39) |

| SEPT9 | Septin-9 | 0.45 | 0.64 | 6 | Yes (40) |

| TLE3 | Transducin-like enhancer protein 3 | 2.46 | 1.24 | 3 | No |

| ALDH1A3 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase family 1 member A3 | 2.08 | 1.02 | 2 | No |

| DDX11 | Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase | 0.39 | 1.00 | 2 | No |

| FLG | Filaggrin | 13.89 | 1.00 | 3 | No |

| PELP1 | Proline-, glutamic acid- and leucine-rich protein 1 | 2.27 | 1.07 | 15 | No |

| ARPP19 | cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein 19 | 2.34 | NDa | 5 | No |

| CDC45L | CDC45-related protein | 0.48 | ND | 1 | Yes (41) |

| CSTA | Cystatin-A | 11.24 | ND | 3 | Yes (42, 43) |

| FN1 | Fibronectin | 6.25 | ND | 4 | Yes (44) |

| FOSL1 | Fos-related antigen 1 | 0.35 | ND | 2 | Yes (45) |

| JUP | Junction plakoglobin | 18.52 | ND | 12 | Yes (46) |

| KIF11 | Kinesin-like protein | 0.40 | ND | 11 | Yes (47) |

| PNPLA6 | Neuropathy target esterase | 2.00 | ND | 9 | No |

| RRM2 | Ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase subunit M2 | 0.47 | ND | 8 | No |

| S100A7 | Protein S100-A7 | 90.91 | ND | 2 | Yes (48, 49) |

| SFN | 14-3-3 protein sigma | 5.29 | ND | 3 | Yes (50, 51) |

| UHRF1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | 0.33 | ND | 8 | Yes (52) |

a ND: mRNA levels of differentially expressed proteins were not determined by qPCR analysis.

Identification of Potential Cargo Proteins for KPNA2 Based on the Quantitative Nuclear Proteome

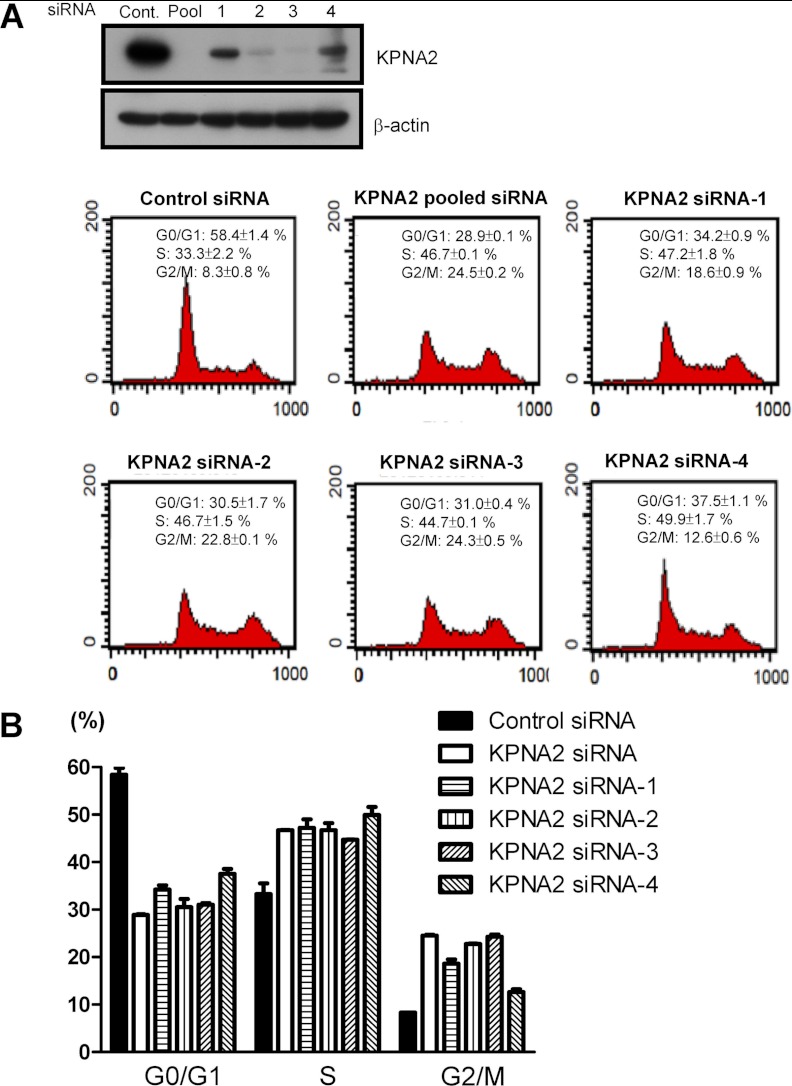

To determine the potential cargo proteins of KPNA2, we focused on those that displayed variable expression in nuclear fractions (nuclear proteome). We hypothesized that nuclear transport of cNLS-bearing cargo proteins of KPNA2 is attenuated or defective in KPNA2 knockdown cells, leading to reduced expressions of cargo and its downstream effectors in the nuclear fraction. Using twofold change as the criterion to select potential cargo proteins, we identified 28 up-regulated and 87 down-regulated proteins in KPNA2 siRNA-transfected nuclear fractions (supplemental Table S6). We used MetaCore software to build biological networks and analyzed the possible biological linkages between these 115 differentially expressed proteins obtained from the nuclear proteome (Table III). We then set several criteria to select the dysregulated networks and targeted proteins for further verification. First, the targeted biological network that was selected from Table III should be with less p-value, high z-score and high g-score that indicate the high possibility and reliability of targeted network. Second, more identified proteins (root nodes shown in network) involved in less pathways would be better to narrow down one simple and also important interaction network. For example, there were 18 identified proteins involved in only one pathway showing in the second significant network, Table III. Third, the biological functions of dysregulated proteins should be overlapping with those regulated by KPNA2. Fourth, there are potential novel cargo proteins of KPNA2 shown in the target networks. Accordingly, Fig. 3A showed the top significant network and concluded that the proteins are mainly regulated by two transcription factors, p53 and c-Myc (Fig. 3A). This result was supported by previous data showing that both p53 and c-Myc interact with KPNA2 through their cNLS sequences (53, 54). We then performed the co-immunoprecipitation assay to examine the interaction between KPNA2 and these two cargo proteins in lung cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 3B, the endogenous p53 and c-Myc proteins were co-immunoprecipitated with KPNA2, respectively. This result suggests that the quantitative proteomics method combined with MetaCore analysis is reliable and feasible for discovery of cargo proteins for KPNA2. We then applied this integrated approaches to search for novel cargo proteins of KPNA2. As specified earlier, cell viability was decreased in KPNA2 knockdown cells (23). We further tested the possibility of KPNA2 involvement in the cell cycle via flow cytometry analysis. As shown in Fig. 4A, we found that KPNA2 production was efficiently down-regulated by pooled and also every single siRNAs (siRNA-1, 2, 3 and 4) transfected CL1-5 cells. The flow cytometry analysis revealed that cell cycle arrested in the G2/M phase was observed in cells transfected with pooled siRNA, siRNA-2 or siRNA-3, whereas siRNA-1 and siRNA-4 were less potent (Fig. 4B). Accordingly, we focused on the second significant network involving DNA metabolic process, DNA replication and the cell cycle (Fig. 3C). In this second significant network (Fig. 3C), there were three transcription factors, including STAT5A, androgen receptor and E2F1 interact with multiple proteins directly (nodes represent proteins, lines between the nodes indicate direct protein-protein interactions, global nodes highlight the proteins identified in the current study, red bottoms indicate down-regulated proteins and blue bottoms indicate up-regulated proteins in KPNA2 knockdown cells). Notably, E2F1 is the master molecule with maximal lines between nodes, in which 18 differentially expressed proteins identified in this study are shown to interact with E2F1, including ATAD2, BARD1, BLM, CDK6, CLSPN, DBF4, JMJD6, MAT2A, MCM10, MYH10, NBN, PAF, PMS2, POLA1, POLA2, PRIM2, UGDH, and UHRF1 (Fig. 3C and Table IV). Among these proteins, seven proteins (ATAD2, BLM, CDK6, CLSPN, DBF4, NBN, and UHRF1) have been reported as dysregulated in lung cancer (Table IV) (22, 55–60). Accordingly, we suggest E2F1 would be the key transcription factor responsible for biological processes in the second significant network. To our knowledge, E2F1 is a potent transcription factor that exerts tumor-promoting effects in multiple cancers, including lung cancer, breast cancer, and thyroid cancer (61–64). E2F1 elicits the expression of genes involved in progression through the G2 and M stages (65–67), similar to the functional characteristics of KPNA2 examined in the current study (Fig. 4). To validate that E2F1 plays a central role in this network (Fig. 3C), mRNA levels of 12 differentially expressed proteins regulated by E2F1 were further examined successfully using qPCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 3D and Table IV, CLSPN, DBF4, JMJD6, MCM10, POLA1, POLA2, PMS2, and UGDH mRNA levels were decreased with average ratios of 0.52, 0.65, 0.73, 0.80, 0.52, 0.65, 0.75, and 0.57-fold, respectively, upon KPNA2 knockdown compared with control cells. The gene levels of ATAD2, BARD1, MYH10, and NBN were slightly altered with average ratios of 1.03, 1.00, 1.12, and 1.11-fold, respectively upon KPNA2 knockdown. Our results imply that E2F1 is the sole transcription factor response for biological processes in the second significant network. These results collectively suggest that KPNA2-mediated tumorigenesis occurs through the regulation of several master transcription factors, such as p53, c-Myc, and E2F1.

Table III. Biological networks in which 115 differently expressed proteins identified in the nuclear proteome are involved.

| No | GO processes | Total nodes | Root nodes | Pathway | p-Value | z-Score | g-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Response to DNA damage stimulus (46.0%), DNA metabolic process (46.0%), DNA repair (38.0%) | 50 | 25 | 5 | 1.53e-52 | 70.06 | 76.31 |

| 2 | DNA metabolic process (48.0%), DNA replication (30.0%), cell cycle (46.0%) | 51 | 18 | 1 | 1.53e-34 | 49.84 | 51.09 |

| 3 | Regulation of actin polymerization or depolymerization (11.6%), organelle organization (34.9%), cellular component movement (23.3%) | 50 | 17 | 0 | 6.77e-33 | 49.04 | 49.04 |

| 4 | DNA metabolic process (43.8%), cell cycle (45.8%), cell cycle phase (33.3%) | 50 | 16 | 2 | 5.37e-30 | 44.71 | 47.21 |

| 5 | Response to stress (52.1%), response to organic substance (41.7%), response to stimulus (68.8%) | 50 | 15 | 0 | 1.08e-27 | 41.89 | 41.89 |

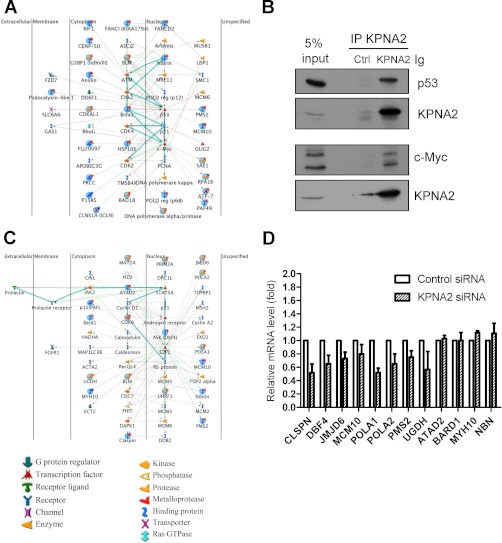

Fig. 3.

Biological network of KPNA2-regulated proteins identified from the nuclear proteome. Quantitative nuclear proteomic analysis revealed the contribution of several transcription factors to the biological functions of KPNA2. A, The top significant network involving response to DNA damage stimulation, DNA metabolic processes and DNA repair is controlled by p53 and c-Myc. B, KPNA2 interacted with p53 and c-Myc in lung cancer cells. CL1-5 cells were lysed and the resulting cell lysates were analyzed by co-immunoprecipitation assays using anti-KPNA2 antibodies coupled with protein G beads as described under “Experimental Procedures.” After an overnight incubation at 4 °C, the precipitated protein complexes were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-p53, anti-c-Myc and anti-KPNA2 antibodies as indicated. C, The second significant network involving DNA metabolic processes, DNA replication and cell cycle is controlled by E2F1. Nodes represent proteins, lines between the nodes indicate direct protein-protein interactions, and green, red, and gray lines signify positive, negative, and unspecified effects, respectively. Highlighted lines indicate the canonical pathways. Various proteins on the map are indicated with different symbols, representing functional class. Global nodes highlight the proteins identified in the current study. Red bottoms indicate down-regulated proteins and blue bottoms indicate up-regulated proteins in KPNA2 knockdown cells. D, The relative mRNA levels of E2F1-regulated proteins in KPNA2 knockdown cells. Total RNA from control siRNA or KPNA2 siRNA-transfected cells was purified and reverse-transcribed, and the resultant cDNA subjected to qPCR analysis using gene-specific primers. Fold change of the mRNA level for each protein in KPNA2 knockdown cells was calculated as a ratio relative to control treatment. Results were expressed as mean values ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Fig. 4.

Knockdown of KPNA2 in lung cancer cells causes cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase. A, CL1-5 cells were transfected with control siRNA and KPNA2 siRNA, including pool or four individual, respectively. After transfection for 48 h, DNA content was determined by PI staining followed by flow cytometry analysis, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” B, Quantification analysis of cell cycle distributions acquired from (A). Results were expressed as mean values ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Table IV. Eighteen differentially expressed proteins in the second significant network deduced from nuclear proteome analysis.

| Symbol | Recommended name | Protein ratio obtained from nuclear proteome (KPNA2 siRNA/ control siRNA) | Protein ratio obtained from whole proteome (KPNA2 siRNA/ control siRNA) | mRNA ratio obtained from qPCR (KPNA2 siRNA/ control siRNA) | Prediction of cNLS | Unique peptide number | Dysregulated in lung cancer (reference number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLSPN | Claspin | 0.12 | NDa | 0.52 | Yes | 3 | Yes (55) |

| DBF4 | Protein DBF4 homolog A | 0.27 | ND | 0.65 | Yes | 1 | Yes (56) |

| JMJD6 | Histone arginine demethylase | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.73 | Yes | 6 | No |

| MCM10 | Protein MCM10 homolog | 0.28 | ND | 0.80 | Yes | 2 | No |

| POLA1 | DNA polymerase alpha catalytic subunit | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.65 | No | 14 | No |

| POLA2 | DNA polymerase subunit alpha B | 0.35 | 0.53 | 0.52 | Yes | 3 | No |

| PRIM2 | DNA primase large subunit | 0.36 | 0.62 | 0.75 | No | 7 | No |

| UGDH | UDP-gluce 6-dehydrogenase | 0.40 | 0.91 | 0.57 | No | 14 | No |

| ATAD2 | ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 2 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 1.03 | Yes | 15 | Yes (57) |

| BARD1 | BRCA1-associated RING domain protein 1 | 0.43 | ND | 1.00 | Yes | 4 | No |

| MYH10 | Myin-10 | 2.39 | 1.06 | 1.12 | Yes | 27 | No |

| NBN | Nibrin | 0.47 | 0.90 | 1.11 | Yes | 11 | Yes (22) |

| BLM | Bloom syndrome protein | 0.41 | ND | UDb | Yes | 7 | Yes (58) |

| CDK6 | Cell division protein kinase 6 | 0.32 | ND | UD | No | 2 | Yes (59) |

| MAT2A | S-adenylmethionine synthetase isoform type-2 | 0.48 | 0.94 | UD | No | 8 | No |

| PAF | PCNA-associated factor | 0.29 | ND | UD | Yes | 2 | No |

| PMS2 | Mismatch repair endonuclease | 0.41 | ND | UD | No | 2 | No |

| UHRF1 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | 0.34 | 0.33 | UD | Yes | 27 | Yes (52, 60) |

a ND: Protein levels of differentially expressed proteins were not determined in whole proteome analysis.

b UD: mRNA levels of differentially expressed proteins were unable to be detected by qPCR analysis.

KPNA2 Interacts Directly with E2F1

Next, we further confirmed whether E2F1 acts as a novel cargo protein for KPNA2. To examine the specific interactions between KPNA2 and E2F1 in vivo, we initially established the subcellular distributions of these two molecules via immunofluorescence analysis. As shown in Fig. 5A, the subcellular localization of overexpressed KPNA2 in lung cancer cells was enriched in nucleus that is consistent with the overexpressed patterns of KPNA2 in several human cancer tissues, such as lung cancer, breast cancer, ovary cancer, bladder cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (23–28, 30). Because of unavailability of an antibody applicable for immunofluorescence staining of endogenous E2F1 using lung cancer cells, a myc-tagged E2F1 was constructed and expressed in KPNA2-knockdown CL1-5 cells in this study. As expected, KPNA2 was colocalized with E2F1 in lung cancer cells. Moreover, the immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated the association between endogenous E2F1 and KPNA2 in CL1-5 lung cancer cells as well as in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells (NPC-TW02) and HEK293 cells (Fig. 5B and data not shown). An in vitro GST pull-down assay further confirmed the direct interactions between KPNA2 and wild-type E2F1 (Fig. 5C). To determine the binding domains between KPNA2 and E2F1, we searched two potential NLS binding sites, 142W-R238 and 315R-N403 in KPNA2 based on domain structure analysis that deposited in UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P52292). We also used the cNLS Mapper (http://nls-mapper.iab.keio.ac.jp/cgi-bin/NLS_Mapper_form.cgi) to predict 85RPPVKRRLDLE95 (NLS1) and 161KVQKRRIYDI170 (NLS2) as two potential cNLS sites in E2F1. According to this information, four serial deletion constructs of KPNA2 and two deletion constructs of E2F1 were generated for in vitro pull-down assay (Figs. 5C, 5D). As shown in Fig. 5C, we found that the interaction between E2F1 and deletion mutants (KPNA2-D2 and KPNA2-D3) was dramatically decreased, suggesting that the NLS binding domain located in 142W-R238, but not 315R-N403 was necessary for KPNA2 binding to E2F1. Unexpectedly, the production yield and stability of recombinant KPNA2-D4 protein (1–314 a.a.) were too low to be used for this comparative pull-down assay (supplemental Fig. S2). On the other hand, we found that deletion of 85RPPVKRRLDLE95 cNLS site (NLS1) but not 161KVQKRRIYDI170 (NLS2) in E2F1 substantially impaired its binding to KPNA2, suggesting that the NLS1 was essential for E2F1 binding to KPNA2 (Fig. 5D-a). Next, we further dissected the key residues of E2F1 required for KPNA2 binding using site-directed mutagenesis, by which alanine residues were introduced respectively into positions 89–91 (NLS1 mutant construct, M1) and 164–166 (NLS2 mutant construct, M2) for replacement of lysine and arginine residues. The in vitro pull-down assay demonstrated that interactions between KPNA2 and E2F1 with mutated NLS1 are significantly decreased to 42%, compared with those with wild-type E2F1 (Fig. 5D-b). This result suggests that the NLS1 sequence (residues 89–91) of E2F1 was required for E2F1-KPNA2 interactions, consistent with the general characteristics of a cargo protein.

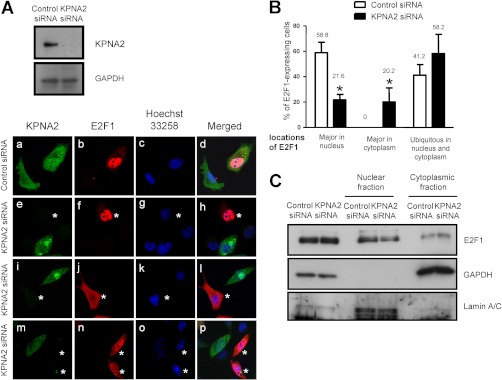

Knockdown of KPNA2 Causes Subcellular Redistribution of E2F1 in Lung Cancer Cells

After establishing that KPNA2 interacts with E2F1, we were interested in determining whether KPNA2 mediates nuclear translocation of E2F1. To examine the effect of KPNA2 on subcellular distribution of E2F1 in lung cancer cells, we applied the siRNA approach to knock down endogenous KPNA2 expression in lung cancer cells that co-expressed myc-tagged E2F1 and then examined the subcellular distribution of E2F1 using an immunofluorescence assay. To simultaneously observe the localization of E2F1 in control siRNA-transfected cells as well as in KPNA2 siRNA-transfected cells, two groups of cells were suspended and mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and then seeded onto coverslips for the immunofluorescence assay. The expression patterns of KPNA2 and myc-tagged E2F1 were detected with anti-KPNA2 and anti-myc antibodies, respectively. The cells transfected with control siRNA were distinguished from cell transfected with KPNA2 siRNA by the relative intensity of fluorescence signals shown in the same micrographs, in which the lower fluorescence intensity of KPNA2 in given cells indicated the KPNA2 siRNA-mediated reduction of KPNA2 expression. As shown in Fig. 6, three different representative distributions of exogenous E2F1 in KPNA2- knockdown cells, specifically, major distribution in the nucleus (Fig. 6A, e–h), major distribution in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6A, i–l), and ubiquitous distribution throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 6A, m–p). To detect alterations in the subcellular distribution of E2F1, image quantification was performed in control and KPNA2- knockdown cells, (n>50 in each group, Fig. 6B). As expected, the proportion of cells with major nuclear E2F1 signals was reduced significantly in the KPNA2 knockdown cell group, compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (58.8 ± 8.3% versus 21.6 ± 4.4%), and cells with major cytoplasmic E2F1 signals were observed in the KPNA2 knockdown, but not the control group (20.2 ± 10.9% versus 0%). In general, the proportion of cells showing cytoplasmic E2F1 signals was increased in KPNA2-knockdown cell group compared with the control group [78.4% (58.2%+20.2%) versus 41.2% (41.2%+0%)] (Fig. 6B) We further confirmed this regulation by subcellular fractionation, followed by Western blotting analysis. Fractionation efficacy was validated by the detection of GAPDH and Lamin A/C in the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively (Fig. 6C). The protein level of E2F1 was normalized to that of the two marker proteins. We found that E2F1 in the cytoplasmic fraction was increased in KPNA2 knockdown cells, compared with that in control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 6C), consistent with the subcellular redistribution observed with immunofluorescence staining experiments (Figs. 6A and 6B). Similar results were observed in HeLa cells (supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that the KPNA2 knockdown-mediated redistribution of E2F1 is not restricted to lung cancer cells. These results collectively suggest that KPNA2 mediates E2F1 transport from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in vivo.

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of KPNA2 causes subcellular redistribution of E2F1 in lung cancer cells. A, CL1-5 cells were transfected with control siRNA and KPNA2 siRNA, respectively, followed by transfection with E2F1/myc plasmid. At 24 h after transfection, cells transfected with KPNA2 siRNA were mixed 1:1 with control siRNA-transfected cells and re-seeded on coverslips for additional 24 h. At 48 h after transfection, cells were prepared for immunofluorescence staining using anti-KPNA2 and anti-myc antibodies to detect endogenous expression of KPNA2 and exogenous expression of E2F1, respectively. Asterisks indicate KPNA2 knockdown cells. B, Quantification analysis of subcellular distribution acquired from immunofluorescence staining. Error bars indicate standard deviation. A p value of less than 0.05 indicates statistical significance using the unpaired Student's t test. C, CL1-5 cells transfected with control siRNA or KPNA2 siRNA, followed by transfection with E2F1/myc plasmid. At 48 h after transfection, cells were lysed and fractionated as nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, followed by Western blotting. GAPDH was used as the cytosolic control and lamin A/C as the nuclear control.

DISCUSSION

KPNA2, a potential tumor marker, has been shown to play important roles in cellular proliferation, differentiation, cell-matrix adhesion, colony formation and migration, using overexpression or knockdown approaches (23, 28–31). However, the detailed molecular mechanisms of KPNA2 action in cancers remain to be clarified. Recently, Noetzel et al. confirmed that KPNA2 acts as a novel oncogenic factor in human breast cancer via detailed phenotypic characterization with overexpression or knockdown experiments in benign and malignant human breast cells. The group showed that up-regulation of RAC1, PCNA, p65, and OCT4 mRNA is associated with KPNA2 overexpression and proposed that these putative downstream effectors of KPNA2 contribute to the malignancy of breast cancer (30). In the current study, we employed the SILAC approach to systematically analyze global protein changes upon KPNA2 knockdown in lung cancer cells. Using this approach, proteins extracted from different cell populations (negative control siRNA and KPNA2 siRNA-transfected cells) can be processed in a single experiment after equal mixing of cell numbers or protein mass, thus minimizing experimental variations, contaminations, and artifacts that originate from separating sample processing (32, 68, 69). The SILAC-based strategy is particularly useful for subcellular proteome analysis because of its consistency through the course of subcellular fractionation on parallel cell populations. We obtained comprehensive data sets of potential proteins regulated by KPNA2, which may be useful to address the molecular mechanisms underlying the phenotypic alterations in KPNA2-overexpressing and knockdown cancer cells.

Several cargo proteins of KPNA2 have been identified to date, including NBN, OCT4, NFKB1, Myc, p53, LEF-1, CHK2, BRCA1, S100A2, S100A6, RECQL, RAC1, and p65 (21, 29, 53, 70–80). Among these proteins, six were detected in the nuclear proteome (NBN, BRCA1, S100A6, TP53 (p53), RECQL, and RAC1) with protein ratios (KPNA2 siRNA/control siRNA) of 0.47, 0.38, 0.98, 0.79, 0.79, and 1.02, respectively (supplemental Table S3). However, E2F1 and c-Myc were not successfully identified or quantified in this study, probably because of their low abundance in CL1-5 lung cancer cells. As shown in supplemental Fig. S4, the Western blotting analyses of several cell lines, including HEK293, HeLa, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, CL1-0, and CL1-5, demonstrated that the endogenous protein level of E2F1 in CL1-5 cells was much lower than that in HEK293, HeLa cells, and MCF-7 cells. Technically, the SILAC-based LC-MS/MS quantitative proteomic method facilitates high-throughput and accurate quantification, but is limited by dynamic range of detection, i.e. the ionic signals derived from high-abundance proteins mask those from low-abundance proteins, such as transcription factors. This may account for the under detection and quantification of E2F1 and c-Myc in our study. Notably, however, 25 differently expressed proteins in the top significant network of the nuclear proteome are regulated by p53 and c-Myc, and 18 differentially expressed proteins in the second significant network interact with E2F1 (Figs. 3A and 3C). These proteins are majorly involved in DNA replication, DNA metabolic process, response to DNA damage stimulus and the cell cycle. Furthermore, qPCR analysis disclosed a decrease in the mRNA levels of eight proteins regulated by E2F1 upon KPNA2 knockdown (Fig. 3D and Table IV), supporting our hypothesis that elimination of KPNA2 leads to suppression of cargo protein transport from the cytoplasm to nucleus and down-regulation of the levels of downstream effectors of these cargo proteins. In conclusion, subcellular quantitative proteome analysis combined with bioinformatics tools effectively facilitated our search for master transcription factors in the interaction network and provided a basis for identifying cargo proteins of KPNA2, such as p53 and c-Myc, and E2F1.

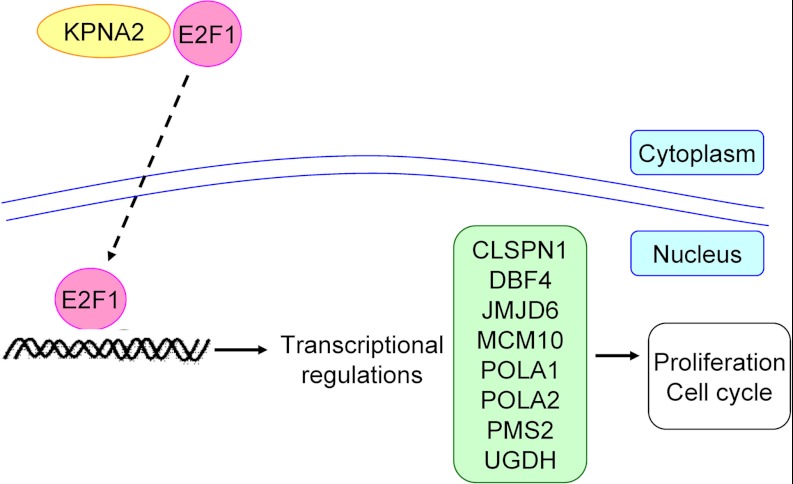

E2F1 belongs to the E2F family of DNA-binding proteins (E2F1 to E2F6), which are central regulators of cell cycle progression, proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival (81–85). Previous studies indicate that many E2F1 regulatory molecules are involved in lung cancer tumorigenesis, such as VEGF, HMGA2, UHRF1, TS, and SKP2 (52, 60, 86–89). To determine the clinical relevance of potential effectors of E2F1 (CLSPN, DBF4, JMJD6, MCM10, POLA1, POLA2, PMS2, and UGDH) identified in the current study (Fig. 3C), we used the Human Protein Atlas version 7.0 database, a public repository of human antibodies, and obtained immunohistochemistry images of their expression patterns in lung cancer and normal tissues. We observed that five proteins (JMJD6, POLA1, POLA2, PMS2, and UGDH) are dysregulated in 49∼89% lung cancer tissues with moderate to strong intensity, supporting our hypothesis that KPNA2-associated E2F1 downstream signaling contributes to lung cancer tumorigenesis (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Hypothetical schematic of the roles of KPNA2 and E2F1 in NSCLC. Nuclear transportation of E2F1 was mediated by KPNA2 through the classical nuclear import pathway. The biological functions of downstream effectors of E2F1 were maintained in cells with normal expression of KPNA2 and E2F1. In NSCLC cells, aberrantly overexpressed KPNA2 or E2F1 triggered dysregulation of downstream effectors of E2F1 and contributed to oncogenesis.

To our knowledge, herein we demonstrated for the first time the regulatory effect of KPNA2 on cell cycle. We found that knockdown of KPNA2 led to a significant arrest of cell cycle at the G2/M phase in CL1-5 and MDA-MB-231, whereas this effect was not apparent in CL1-0 and MCF-7 cells (supplemental Fig. S5). This result was consistent with the previous findings that knockdown of KPNA2 significantly reduced the cell viability in CL1-5 and breast cancer cells but not in CL1-0 cells (23, 30). The underlying mechanism behind these phenotypic alterations is currently unclear and remains to be deciphered. Given the prominent role of KPNA2 in multiple cellular processes that might be associated with cancer progression, future investigations would aim for comparatively analyzing the differential protein complexes of KPNA2 between CL1-5 and CL1-0 cells to reveal the significance of KPNA2-mediated nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of cargos in lung cancer development.

In conclusion, this is the first study to demonstrate that depletion of KPNA2 leads to global changes in the expression patterns of cellular proteins involved in the cell cycle, proliferation and migration, using SILAC quantitative proteomics analysis. We have additionally identified a potential novel cargo protein, E2F1, for KPNA2. Both KPNA2 and E2F1 are overexpressed in multiple human cancers, and our findings provide a new avenue for exploring the roles of these proteins in tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

* This work was supported by grants from the Chang Gung Medical Research Fund (CMRPD 180321-3) and National Science Council, R.O.C. (NSC 97-2320-B-182-026-MY3 and 100-2320-B-182-025) as well as the Ministry of Education, R.O.C. (EMRPD170191).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S5 and Tables S1 to S6.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S5 and Tables S1 to S6.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- cNLS

- classical nuclear localization signal

- KPNA2

- Karyopherin subunit alpha-2

- NSCLC

- nonsmall cell lung cancer

- MRN

- MRE11/RAD50/NBN

- DSB

- double-strand break

- SILAC

- stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture

- 2D LC-MS/MS

- two-dimensional LC-MS/MS

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- SCX

- strong cation exchange

- RP18

- reverse phase 18

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- RT-PCR

- reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR

- real-time quantitative PCR

- PI

- propidium iodide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Radu A., Blobel G., Moore M. S. (1995) Identification of a protein complex that is required for nuclear protein import and mediates docking of import substrate to distinct nucleoporins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 1769–1773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Macara I. G. (2001) Transport into and out of the nucleus. Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 570–594, table of contents [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chook Y. M., Blobel G. (2001) Karyopherins and nuclear import. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 703–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jäkel S., Gölich D. (1998) Importin beta, transportin, RanBP5 and RanBP7 mediate nuclear import of ribosomal proteins in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 17, 4491–4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mosammaparast N., Jackson K. R., Guo Y., Brame C. J., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Pemberton L. F. (2001) Nuclear import of histone H2A and H2B is mediated by a network of karyopherins. J. Cell Biol. 153, 251–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mühlhüusser P., Muller E. C., Otto A., Kutay U. (2001) Multiple pathways contribute to nuclear import of core histones. EMBO Rep. 2, 690–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007) Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotera I., Sekimoto T., Miyamoto Y., Saiwaki T., Nagoshi E., Sakagami H., Kondo H., Yoneda Y. (2005) Importin alpha transports CaMKIV to the nucleus without utilizing importin beta. EMBO J. 24, 942–951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Runnebaum I. B., Kieback D. G., Mobus V. J., Tong X. W., Kreienberg R. (1996) Subcellular localization of accumulated p53 in ovarian cancer cells. Gynecol. Oncol. 61, 266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nakatsuka S., Oji Y., Horiuchi T., Kanda T., Kitagawa M., Takeuchi T., Kawano K., Kuwae Y., Yamauchi A., Okumura M., Kitamura Y., Oka Y., Kawase I., Sugiyama H., Aozasa K. (2006) Immunohistochemical detection of WT1 protein in a variety of cancer cells. Mod. Pathol. 19, 804–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Perren A., Komminoth P., Saremaslani P., Matter C., Feurer S., Lees J. A., Heitz P. U., Eng C. (2000) Mutation and expression analyses reveal differential subcellular compartmentalization of PTEN in endocrine pancreatic tumors compared to normal islet cells. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 1097–1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colombo E., Martinelli P., Zamponi R., Shing D. C., Bonetti P., Luzi L., Volorio S., Bernard L., Pruneri G., Alcalay M., Pelicci P. G. (2006) Delocalization and destabilization of the Arf tumor suppressor by the leukemia-associated NPM mutant. Cancer Res. 66, 3044–3050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lu W., Pochampally R., Chen L., Traidej M., Wang Y., Chen J. (2000) Nuclear exclusion of p53 in a subset of tumors requires MDM2 function. Oncogene 19, 232–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Flamini G., Curigliano G., Ratto C., Astone A., Ferretti G., Nucera P., Sofo L., Sgambato A., Boninsegna A., Crucitti F., Cittadini A. (1996) Prognostic significance of cytoplasmic p53 overexpression in colorectal cancer. An immunohistochemical analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 32A, 802–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldfarb D. S., Corbett A. H., Mason D. A., Harreman M. T., Adam S. A. (2004) Importin alpha: a multipurpose nuclear-transport receptor. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Teng S. C., Wu K. J., Tseng S. F., Wong C. W., Kao L. (2006) Importin KPNA2, NBS1, DNA repair and tumorigenesis. J. Mol. Histol. 37, 293–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carney J. P., Maser R. S., Olivares H., Davis E. M., Le Beau M., Yates J. R., 3rd, Hays L., Morgan W. F., Petrini J. H. (1998) The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell 93, 477–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee J. H., Paull T. T. (2005) ATM activation by DNA double-strand breaks through the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 complex. Science 308, 551–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tauchi H., Kobayashi J., Morishima K., van Gent D. C., Shiraishi T., Verkaik N. S., vanHeems D., Ito E., Nakamura A., Sonoda E., Takata M., Takeda S., Matsuura S., Komatsu K. (2002) Nbs1 is essential for DNA repair by homologous recombination in higher vertebrate cells. Nature 420, 93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu X., Ranganathan V., Weisman D. S., Heine W. F., Ciccone D. N., O'Neill T. B., Crick K. E., Pierce K. A., Lane W. S., Rathbun G., Livingston D. M., Weaver D. T. (2000) ATM phosphorylation of Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein is required in a DNA damage response. Nature 405, 477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tseng S. F., Chang C. Y., Wu K. J., Teng S. C. (2005) Importin KPNA2 is required for proper nuclear localization and multiple functions of NBS1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39594–39600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen Y. C., Su Y. N., Chou P. C., Chiang W. C., Chang M. C., Wang L. S., Teng S. C., Wu K. J. (2005) Overexpression of NBS1 contributes to transformation through the activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 32505–32511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang C. I., Wang C. L., Wang C. W., Chen C. D., Wu C. C., Liang Y., Tsai Y. H., Chang Y. S., Yu J. S., Yu C. J. (2011) Importin subunit alpha-2 is identified as a potential biomarker for non-small cell lung cancer by integration of the cancer cell secretome and tissue transcriptome. Int. J. Cancer 128, 2364–2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dahl E., Kristiansen G., Gottlob K., Klaman I., Ebner E., Hinzmann B., Hermann K., Pilarsky C., Dürst M., Klinkhammer-Schalke M., Blaszyk H., Knuechel R., Hartmann A., Rosenthal A., Wild P. J. (2006) Molecular profiling of laser-microdissected matched tumor and normal breast tissue identifies karyopherin alpha2 as a potential novel prognostic marker in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 3950–3960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sakai M., Sohda M., Miyazaki T., Suzuki S., Sano A., Tanaka N., Inose T., Nakajima M., Kato H., Kuwano H. (2010) Significance of karyopherin-{alpha} 2 (KPNA2) expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 30, 851–856 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jensen J. B., Munksgaard P. P., Sørensen C. M., Fristrup N., Birkenkamp-Demtroder K., Ulhoi B. P., Jensen K. M., Orntoft T. F., Dyrskjot L. (2011) High expression of karyopherin-alpha2 defines poor prognosis in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer and in patients with invasive bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Eur. Urol 59, 841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zheng M., Tang L., Huang L., Ding H., Liao W. T., Zeng M. S., Wang H. Y. (2010) Overexpression of karyopherin-2 in epithelial ovarian cancer and correlation with poor prognosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 116, 884–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mortezavi A., Hermanns T., Seifert H. H., Baumgartner M. K., Provenzano M., Sulser T., Burger M., Montani M., Ikenberg K., Hofstädter F., Hartmann A., Jaggi R., Moch H., Kristiansen G., Wild P. J. (2011) KPNA2 expression is an independent adverse predictor of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 1111–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Umegaki N., Tamai K., Nakano H., Moritsugu R., Yamazaki T., Hanada K., Katayama I., Kaneda Y. (2007) Differential regulation of karyopherin alpha 2 expression by TGF-beta1 and IFN-gamma in normal human epidermal keratinocytes: evident contribution of KPNA2 for nuclear translocation of IRF-1. J. Invest. Dermatol. 127, 1456–1464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noetzel E., Rose M., Bornemann J., Gajewski M., Knüchel R., Dahl E. (2012) Nuclear transport receptor karyopherin-alpha2 promotes malignant breast cancer phenotypes in vitro. Oncogene 31, 2101–2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hall M. N., Griffin C. A., Simionescu A., Corbett A. H., Pavlath G. K. (2011) Distinct roles for classical nuclear import receptors in the growth of multinucleated muscle cells. Dev. Biol. 357, 248–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhu H., Pan S., Gu S., Bradbury E. M., Chen X. (2002) Amino acid residue specific stable isotope labeling for quantitative proteomics. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom 16, 2115–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chu Y. W., Yang P. C., Yang S. C., Shyu Y. C., Hendrix M. J., Wu R., Wu C. W. (1997) Selection of invasive and metastatic subpopulations from a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 17, 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li Y., Yu J., Wang Y., Griffin N. M., Long F., Shore S., Oh P., Schnitzer J. E. (2009) Enhancing identifications of lipid-embedded proteins by mass spectrometry for improved mapping of endothelial plasma membranes in vivo. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 1219–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cox J., Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cox J., Matic I., Hilger M., Nagaraj N., Selbach M., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2009) A practical guide to the MaxQuant computational platform for SILAC-based quantitative proteomics. Nat. Protoc. 4, 698–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Furukawa C., Daigo Y., Ishikawa N., Kato T., Ito T., Tsuchiya E., Sone S., Nakamura Y. (2005) Plakophilin 3 oncogene as prognostic marker and therapeutic target for lung cancer. Cancer Res. 65, 7102–7110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang I. M., Stepaniants S., Boie Y., Mortimer J. R., Kennedy B., Elliott M., Hayashi S., Loy L., Coulter S., Cervino S., Harris J., Thornton M., Raubertas R., Roberts C., Hogg J. C., Crackower M., O'Neill G., Paré P. D. (2008) Gene expression profiling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177, 402–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simpson D. S., Mason-Richie N. A., Gettler C. A., Wikenheiser-Brokamp K. A. (2009) Retinoblastoma family proteins have distinct functions in pulmonary epithelial cells in vivo critical for suppressing cell growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 69, 8733–8741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scott M., Hyland P. L., McGregor G., Hillan K. J., Russell S. E., Hall P. A. (2005) Multimodality expression profiling shows SEPT9 to be overexpressed in a wide range of human tumours. Oncogene 24, 4688–4700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tomita Y., Imai K., Senju S., Irie A., Inoue M., Hayashida Y., Shiraishi K., Mori T., Daigo Y., Tsunoda T., Ito T., Nomori H., Nakamura Y., Kohrogi H., Nishimura Y. (2011) A novel tumor-associated antigen, cell division cycle 45-like can induce cytotoxic T-lymphocytes reactive to tumor cells. Cancer Sci. 102, 697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krepela E., Procházka J., Kárová B., Cermák J., Roubková H. (1998) Cysteine proteases and cysteine protease inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasma 45, 318–331 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ebert E., Werle B., Jülke B., Kopitar-Jerala N., Kos J., Lah T., Abrahamson M., Spiess E., Ebert W. (1997) Expression of cysteine protease inhibitors stefin A, stefin B, and cystatin C in human lung tumor tissue. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 421, 259–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Skrzypski M., Jassem E., Taron M., Sanchez J. J., Mendez P., Rzyman W., Gulida G., Raz D., Jablons D., Provencio M., Massuti B., Chaib I., Perez-Roca L., Jassem J., Rosell R. (2008) Three-gene expression signature predicts survival in early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4794–4799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adiseshaiah P., Lindner D. J., Kalvakolanu D. V., Reddy S. P. (2007) FRA-1 proto-oncogene induces lung epithelial cell invasion and anchorage-independent growth in vitro, but is insufficient to promote tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 67, 6204–6211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamashita T., Uramoto H., Onitsuka T., Ono K., Baba T., So T., So T., Takenoyama M., Hanagiri T., Oyama T., Yasumoto K. (2010) Association between lymphangiogenesis-/micrometastasis- and adhesion-related molecules in resected stage I NSCLC. Lung Cancer 70, 320–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Saijo T., Ishii G., Ochiai A., Yoh K., Goto K., Nagai K., Kato H., Nishiwaki Y., Saijo N. (2006) Eg5 expression is closely correlated with the response of advanced non-small cell lung cancer to antimitotic agents combined with platinum chemotherapy. Lung Cancer 54, 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhang H., Zhao Q., Chen Y., Wang Y., Gao S., Mao Y., Li M., Peng A., He D., Xiao X. (2008) Selective expression of S100A7 in lung squamous cell carcinomas and large cell carcinomas but not in adenocarcinomas and small cell carcinomas. Thorax 63, 352–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhang H., Wang Y., Chen Y., Sun S., Li N., Lv D., Liu C., Huang L., He D., Xiao X. (2007) Identification and validation of S100A7 associated with lung squamous cell carcinoma metastasis to brain. Lung Cancer 57, 37–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xiao G., Lu Q., Li C., Wang W., Chen Y., Xiao Z. (2010) Comparative proteome analysis of human adenocarcinoma. Med. Oncol. 27, 346–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li D. J., Deng G., Xiao Z. Q., Yao H. X., Li C., Peng F., Li M. Y., Zhang P. F., Chen Y. H., Chen Z. C. (2009) Identificating 14–3-3 sigma as a lymph node metastasis-related protein in human lung squamous carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 279, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Unoki M., Daigo Y., Koinuma J., Tsuchiya E., Hamamoto R., Nakamura Y. (2010) UHRF1 is a novel diagnostic marker of lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 103, 217–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim I. S., Kim D. H., Han S. M., Chin M. U., Nam H. J., Cho H. P., Choi S. Y., Song B. J., Kim E. R., Bae Y. S., Moon Y. H. (2000) Truncated form of importin alpha identified in breast cancer cell inhibits nuclear import of p53. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23139–23145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nadler S. G., Tritschler D., Haffar O. K., Blake J., Bruce A. G., Cleaveland J. S. (1997) Differential expression and sequence-specific interaction of karyopherin alpha with nuclear localization sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 4310–4315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tsimaratou K., Kletsas D., Kastrinakis N. G., Tsantoulis P. K., Evangelou K., Sideridou M., Liontos M., Poulias I., Venere M., Salmas M., Kittas C., Halazonetis T. D., Gorgoulis V. G. (2007) Evaluation of claspin as a proliferation marker in human cancer and normal tissues. J. Pathol. 211, 331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Bonte D., Lindvall C., Liu H., Dykema K., Furge K., Weinreich M. (2008) Cdc7-Dbf4 kinase overexpression in multiple cancers and tumor cell lines is correlated with p53 inactivation. Neoplasia 10, 920–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Caron C., Lestrat C., Marsal S., Escoffier E., Curtet S., Virolle V., Barbry P., Debernardi A., Brambilla C., Brambilla E., Rousseaux S., Khochbin S. (2010) Functional characterization of ATAD2 as a new cancer/testis factor and a predictor of poor prognosis in breast and lung cancers. Oncogene 29, 5171–5181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matakidou A., el Galta R., Webb E. L., Rudd M. F., Bridle H., Eisen T., Houlston R. S. (2007) Genetic variation in the DNA repair genes is predictive of outcome in lung cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 16, 2333–2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Igarashi K., Masaki T., Shiratori Y., Rengifo W., Nagata T., Hara K., Oka T., Nakajima J., Hisada T., Hata E., Omata M. (1999) Activation of cyclin D1-related kinase in human lung adenocarcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 81, 705–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Daskalos A., Oleksiewicz U., Filia A., Nikolaidis G., Xinarianos G., Gosney J. R., Malliri A., Field J. K., Liloglou T. (2011) UHRF1-mediated tumor suppressor gene inactivation in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 117, 1027–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gorgoulis V. G., Zacharatos P., Mariatos G., Kotsinas A., Bouda M., Kletsas D., Asimacopoulos P. J., Agnantis N., Kittas C., Papavassiliou A. G. (2002) Transcription factor E2F-1 acts as a growth-promoting factor and is associated with adverse prognosis in non-small cell lung carcinomas. J. Pathol. 198, 142–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eymin B., Gazzeri S., Brambilla C., Brambilla E. (2001) Distinct pattern of E2F1 expression in human lung tumours: E2F1 is upregulated in small cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene 20, 1678–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang S. Y., Liu S. C., Al-Saleem L. F., Holloran D., Babb J., Guo X., Klein-Szanto A. J. (2000) E2F-1: a proliferative marker of breast neoplasia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 9, 395–401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Saiz A. D., Olvera M., Rezk S., Florentine B. A., McCourty A., Brynes R. K. (2002) Immunohistochemical expression of cyclin D1, E2F-1, and Ki-67 in benign and malignant thyroid lesions. J. Pathol. 198, 157–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Cam H., Dynlacht B. D. (2003) Emerging roles for E2F: beyond the G1/S transition and DNA replication. Cancer Cell 3, 311–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Seguin L., Liot C., Mzali R., Harada R., Siret A., Nepveu A., Bertoglio J. (2009) CUX1 and E2F1 regulate coordinated expression of the mitotic complex genes Ect2, MgcRacGAP, and MKLP1 in S phase. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 570–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Molina-Privado I., Rodriguez-Martinez M., Rebollo P., Martin-Pérez D., Artiga M. J., Menárguez J., Flemington E. K., Piris M. A., Campanero M. R. (2009) E2F1 expression is deregulated and plays an oncogenic role in sporadic Burkitt's lymphoma. Cancer Res. 69, 4052–4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ibarrola N., Kalume D. E., Gronborg M., Iwahori A., Pandey A. (2003) A proteomic approach for quantitation of phosphorylation using stable isotope labeling in cell culture. Anal. Chem. 75, 6043–6049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]