Abstract

Since the discovery of Mdm2, the contribution of this RING E3 ubiquitin ligase to the pathobiology of cancer has focused almost exclusively on its role as a negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor. Under normal conditions, Mdm2 promotes the ubiquitin- and proteasome-dependent degradation of p53. Levels of p53 are thus kept sufficiently low to allow for cell survival and cell cycle progression. In the context of such insults as DNA damage or ribosomal stress, however, the Mdm2-p53 interaction is disrupted and p53 is stabilized. The myriad intracellular outcomes of p53 activation together comprise a robust program of tumor suppression that is short-circuited in cancer. Over half of all human malignancies are known to have lost p53 expression or sustained p53 mutation, whereas many of the remaining tumors harbor other alterations in key mediators of p53 activity that include overexpression of Mdm2. Therapies targeting the interaction between Mdm2 and p53 represent a possible means of pharmacologically reactivating the p53 pathway in this latter setting. The degree of overlap across the biological consequences of either p53 loss or Mdm2 overexpression, however, has not been thoroughly explored. Indeed, a body of evidence for several p53-independent functions of Mdm2 suggests that disrupting the Mdm2-p53 interaction may fail to address the full spectrum of oncogenic effects specific to tumors that overexpress Mdm2.

Keywords: Mdm2, p53, cancer, tumorigenesis, cell cycle

Introduction

The MDM2 gene was originally cloned from a spontaneously transformed mouse 3T3 cell line.1 Molecular analysis revealed that the gene was heavily amplified in these cells. Early studies in cell culture demonstrated that Mdm2 overexpression rendered rodent fibroblasts tumorigenic in nude mice.2,3 Since these initial reports, Mdm2 has been extensively described as a physiologic antagonist of p53, a role that has become central to its putative function as an oncogene.

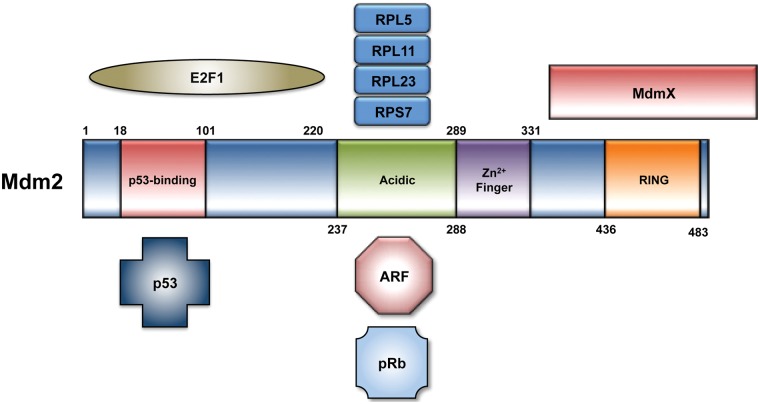

Mdm2 binds the N-terminal of p53 and masks the transactivation domain required for p53 transcriptional activity.4,5 Mdm2 also functions as a RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets p53 for degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system.6-8 The RING finger further comprises a binding site for MdmX, a closely related heterodimerization partner of Mdm2 that has been reviewed elsewhere.9 Multiple cellular stresses are capable of disrupting the Mdm2-p53 interaction. Proteins involved in the DNA damage response can promote p53 stability and activation following genotoxic stress, for example, through a series of posttranslational modifications on both Mdm2 and p53.10,11 In response to oncogenic signaling stress, the p14ARF protein is transcriptionally upregulated and binds the central domain of Mdm2, impairing the ability of Mdm2 to regulate p53.12 Similarly, nucleolar stress can result in the release of ribosomal proteins from the nucleolus, several of which have been shown to bind Mdm2 and stabilize p53 (Fig. 1).13

Figure 1.

The 491 amino acids that comprise the Mdm2 protein can be subdivided into an N-terminal p53 binding domain, a central acidic domain and adjacent zinc finger domain, and a C-terminal RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase domain. There is considerable overlap across the N-terminal domain of Mdm2 that binds p53 and E2F1. Key regulators of Mdm2 activity, including ARF and ribosomal proteins, interact with Mdm2 at its acidic domain. Mdm2 has also been shown to require residues 254 to 264 in this region for its interaction with pRb.

When activated, p53 positively regulates Mdm2 expression.14 It has recently been proposed that phosphorylation of Mdm2 at serine 395, conferred by the ATM kinase in the setting of DNA damage, promotes allosteric remodeling of the Mdm2 RING domain, binding of p53 mRNA, and enhanced p53 protein translation.15,16 The 2 proteins thus participate in an autoregulatory feedback loop that both restrains p53 function under normal conditions and drives p53 activation under stress. The importance of this interplay, at least from a development standpoint, is evidenced by the finding that MDM2 −/− mice die early in embryonic development but are rescued in a p53 −/− background.17,18

These and additional data from human tumors collectively support an oncogenically relevant role for Mdm2 that rests on its ability to negatively regulate the stability and transcriptional activity of p53, thereby abrogating the tumor-suppressive effects of this pathway. Nevertheless, investigations in this field warrant reexamination. Methods employed to drive Mdm2 overexpression in cell culture, for example, have not yielded consistent results. Divergent experimental strategies have yielded data supporting discrepant conclusions regarding the role of Mdm2 in tumorigenesis that remain unresolved. These and other aspects of this work will be discussed in greater detail in the sections that follow.

Modeling Mdm2 Overexpression in Cells: Different Contexts, Different Methods, and Contradictory Conclusions

Initial studies of Mdm2 in cell culture suggested that Mdm2 was an oncogene.2,3 These investigations employed a cosmid vector harboring the bacterial neo gene, mouse DHFR gene, and the full-length genomic equivalent of MDM2. By subjecting transfected cells to increasing doses of methotrexate, investigators were able to select for those clones that had coamplified MDM2 with DHFR. Stable clones of 3T3 and Rat2 cells overexpressing Mdm2 produced tumors in transplanted mice.2 These tumors were subsequently shown to overexpress MDM2 by Northern blot analysis, but expression of Mdm2 protein was not assessed. Using the same approach, MDM2 overexpression was shown to cooperate with activated Ras in a series of transformation assays.3 Co-transfection of MDM2 and T24-ras in primary rat embryo fibroblasts (REFs) produced a 14-fold increase in the number of foci observed. In addition, REFs that had received both MDM2 and T24-ras could be cloned into stable lines, a feature not observed in REFs that received T24-ras alone.

Although these early findings en- dorsed an oncogenic role for Mdm2, several aspects of these studies merit further discussion. First, the number of foci observed in REFs that received both MDM2 and T24-ras was not equal to that observed in REFs that received both mutant p53 and T24-ras (28 vs. 45, respectively). These data suggest that at least certain effects of Mdm2 overexpression and p53 mutation may be nonredundant. Second, an association between endogenous rat p53 and transfected (murine) Mdm2 was not detected in transformed REFs. These findings further hinted that p53-independent functions of Mdm2 may play an important role in this model of transformation.

Results of more recent studies investigating the effects of Mdm2 overexpression in cells suggest that Mdm2 may be antiproliferative under certain circumstances (Table 1). Nontransformed human and rodent cells can select against Mdm2 expression in the formation of stable clones.19 The same effect has not been consistently observed in tumor lines, although the reasons for discrepancies between studies are not clear.7 Nevertheless, nontransformed cells transiently transfected with full-length Mdm2 cDNA arrest at G0/G1 when analyzed by flow cytometry, whereas tumor-derived cells do not.19 Through the use of deletion mutants, growth inhibitory domains of Mdm2 have been mapped to amino acid residues 155 to 220 (ID1) and 270 to 324 (ID2). The absence of one or both of these domains has been shown to enhance the tumorigenicity of transfected 3T3 cells in nude mice, and neither domain appears to be directly involved in the physical interaction of Mdm2 with p53.19 Mutations in ID2 have also been observed in MDM2 sequenced from human tumors in other studies.20

Table 1.

Summary of Selected Studies of Mdm2 Overexpression in Cell Culture

| Study | Overexpression Model | Cells Studied | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fakharzadeh et al., 19912 | Amplified genomic mdm2 a | Rat2, NIH 3T3 | • 100% of nude mice receiving transfected cells developed tumors. |

| Finlay, 19933 | Amplified genomic mdm2 a | 1° REFs | • Cells receiving Ras+Mdm2 showed an increase in foci and 100% clonability, and they formed tumors when injected into nude mice. |

| • Co-transfection of Ras+Mdm2+wtp53 reduced the numbers of foci. | |||

| • No interaction between transfected Mdm2 and endogenous p53 was observed. | |||

| Brown et al., 199819 | Mdm2 cDNAb | NIH 3T3 | • Nontransformed cells, but not tumor cell lines, failed to produce stable colonies expressing transfected Mdm2. |

| 1° MEFs | • Nontransformed cells, but not tumor cell lines, transfected with Mdm2 arrested in G0/G1. | ||

| WI-38, U2OS, Saos-2, H1299, 21PT | • Putative antiproliferative effects of Mdm2 appeared to depend on domains of the protein distinct from that required for p53 interaction. | ||

| Kubbutat et al., 19977 | Mdm2 cDNAb | U2OS, MCF7 | • Wild-type Mdm2 could not be stably overexpressed in cell lines tested. |

| Dang et al., 200223 | Mdm2 cDNAc | MEFs, pre–B cells | • Cells that received full-length Mdm2 proliferated more rapidly and saturated at a higher density than empty-vector controls; the opposite was noted when truncated Mdm2 constructs lacking the p53 binding domain were used. |

Refers to a cosmid vector containing amplified copies of mdm2 under the control of its native promoter.

Refers to a plasmid expression vector harboring the full-length cDNA (or truncations, as indicated) of Mdm2 under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter.

Refers to a plasmid expression vector harboring the full-length cDNA (or truncations, as indicated) of Mdm2 under the control of the murine stem cell virus (MSCV) promoter.

The observation that exogenous Mdm2 can prevent progression through the cell cycle suggests that Mdm2 may be functioning more like a tumor suppressor than an oncogene. Although these findings are at odds with data from earlier investigations, the methods used to drive Mdm2 overexpression have not been uniform. Groups that embraced an oncogenic role for Mdm2 reported differences in the transformation ability of the MDM2 cosmid versus cDNA expression plasmids in 3T3 cells.21 It is tempting to speculate that overexpression of genomic MDM2 may allow for an abundance of pro-transformation splice variants that are not permitted when full-length cDNA is employed. More than 40 distinct splice variants of mouse and human Mdm2 have been reported in a variety of tumors and cell lines, but their precise roles remain elusive.22 Many variants do not contain the binding site for p53, and several have been shown to inhibit proliferation following transfection of respective cDNA expression vectors into primary mouse embryo fibroblasts.23 Similar antiproliferative effects were not seen in a p53 −/− setting, and it has been proposed that the relevant functions of full-length Mdm2 may be inhibited by these splice variants.23 The increase in p53 stability that would be expected under these circumstances, however, is mechanistically inconsistent with an oncogenic role for these isoforms. Furthermore, it has yet to be determined whether all variant transcripts detected to date are actually translated into protein.

Many p53-independent functions of Mdm2 have been suggested in the wake of these findings. A role for Mdm2 in promoting S phase entry through its interactions with pRb and E2F1, for example, has been the subject of much study and is discussed below. Indeed, a growing body of work, including Mdm2 overexpression in vivo, suggests that the role of Mdm2 in neoplasia may not be as straightforward as once supposed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Selected Mouse Models of Mdm2 Overexpression

| Study | Mouse Model(s) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Jones et al., 1998 | Amplified genomic mdm2 | Adult tissues with 4-fold Mdm2 overexpression. |

| 50% homozygotes developed tumors at 61 weeks. | ||

| 38% tumors in Mdm2-tg animals were sarcomas, as opposed to 9% in p53–/– animals. | ||

| No effect of p53 status on tumor latency or spectrum. | ||

| Lundgren et al., 199726 | Targeted overexpression of mdm2 cDNA in the mouse mammary gland | 10- to 30-fold increase in Mdm2 expression in mammary epithelial cells over wild-type controls. |

| Mdm2-expressing mouse mammary epithelial cells had a high S phase index and were polyploid. Tumors seen after a latency of 14 to 18 months. | ||

| Abnormal mammary gland development and tumor formation were independent of p53 and E2F1 status (Reinke et al.27). | ||

| McDonnell et al., 199925 | p53–/–mdm2–/–, p53–/–mdm2+/– p53–/–mdm2+/+ | p53–/–mdm2+/– mice had a longer tumor latency and higher fraction of sarcomas over p53–/–mdm2+/+ or p53–/–mdm2–/– (45% vs 8% vs 10%). |

Mice Overexpressing Mdm2 Develop Spontaneous Tumors along a Histopathologic Spectrum That Is Distinct from p53 −/− Mice and Display Phenotypes Independent of p53 Status

Jones et al.24 described the effects of global overexpression of Mdm2 using an Mdm2-transgenic mouse line. The mouse was generated using the same genomic construct as that which had been used in early cell culture studies.2,3 Blastocyst injections with clones of ES cells overexpressing MDM2 2-, 6-, 9-, and 15-fold were undertaken. Only those clones with 2-fold overexpression of MDM2 produced chimeric mice, however, despite the presence of 25 copies of the gene. This result suggests a possible selective pressure against a threshold level of MDM2 expression that may be incompatible with embryogenesis. Adult tissues, in contrast, demonstrated a 4-fold increase in MDM2 expression compared with wild-type controls.

The Mdm2-transgenic mice in this study developed tumors at an accelerated rate compared with wild-type mice. Mice homozygous for the transgene (MDM2 m1/m1) developed tumors more rapidly than their heterozygous counterparts (MDM2 m1/+; 50% developed neoplasia at 61 weeks vs 87 weeks, respectively), but both were slower than p53 −/− mice. No difference in tumor latency was observed in p53 −/− and MDM2 m1/m1 p53 −/− animals. Most notable were the differences in tumor spectrum: MDM2 m1/m1 and MDM2 m1/m1 p53 –/– developed a high fraction of sarcomas (38% sarcomas in both), in contrast to the predominance of lymphomas seen in p53 –/– mice (83% lymphomas, 9% sarcomas). Interestingly, a similar tumor latency and spectrum was observed in a separate study examining MDM2 +/– p53 –/– mice: p53 –/– mice that were heterozygous for MDM2 had a longer tumor latency and an increase in sarcomas compared with those that were either MDM2 +/+ or MDM2 −/− (45% sarcomas vs 8% and 10%, respectively).25 Together, these studies support the possibility that Mdm2 may be playing a dose- and tissue-selective role in tumor formation.

A transgenic mouse with targeted overexpression of Mdm2 to the mammary gland has also been described.26 To generate this mouse, investigators employed an MDM2 minigene construct (BLGMDM2) consisting of all exons and introns 7 and 8 of the MDM2 gene. Mdm2 overexpression was driven in a tissue-specific and hormonally regulated manner by the ovine BLG promoter. The minigene further allowed for detection of construct-specific transcripts by RNAse protection assay, the levels of which were compared with that of the endogenous full-length transcript to confirm relative overexpression of MDM2. Maximal expression of the transgene was observed during pregnancy and lactation and noted to be 10 to 30 times that of endogenous Mdm2. BLGMDM2 mice were found to exhibit abnormal mammary gland development and to develop multiple tumors in multiple mammary glands after a latency of 14 to 18 months. Mammary epithelial cells in BLGMDM2 mice demonstrated a high S phase index and polyploidy in both wild-type and p53 –/– backgrounds, suggesting that Mdm2 may be driving endoreplication in a p53-independent manner. This phenotype was subsequently shown to be independent of E2F1.27 This finding is in contrast to studies in cells that have proposed a role for Mdm2 in controlling the G1-S cell cycle transition by virtue of its interactions with pRb and E2F1.28-33

An Expanding Set of p53-Independent Functions Suggests Unique Contributions of Mdm2 Overexpression to Tumorigenesis

The ability to interact with the pRb-E2F1 complex and drive E2F1-dependent transcription and cell cycle progression was among the first p53-independent functions of Mdm2 to be proposed. An initial study showed that Mdm2 was able to directly bind E2F1 and its heterodimerization partner DP-1.28 The interaction between Mdm2 and E2F1, but not Mdm2 and DP-1, was shown to stimulate E2F1 transcriptional activation by reporter assay, although a mechanism was not clear. These results, which were generated in a p53- and RB-null cell line (Saos2), further argued that the Mdm2-E2F1 relationship was independent of either p53 or pRb. A separate report, however, identified stable complexes between Mdm2 and the C-terminal region of pRb in an RB-replete cell line (U2OS) by co-immunoprecipitation.29 In this study, co-transfection of Mdm2 into cells with a phosphorylation-resistant, hyperactive pRb mutant promoted endogenous E2F1 transcriptional activity and S phase entry that were both otherwise strongly inhibited. Similar results were obtained in a p53-null cell line, validating the p53-independent nature of this outcome. Although the authors did not rule out a role for a direct interaction between Mdm2 and E2F1, their findings argued that Mdm2 could directly prevent pRb suppression of E2F1 activity.

More recent efforts have attempted to elucidate the mechanism by which Mdm2 stimulates a G1-S transition through its interaction with either pRb or E2F1. Mdm2 preferentially binds hypophosphorylated pRb and is able to decrease recruitment of pRb-E2F1 complexes to DNA.33 Failure to recruit pRb, a well-known transcriptional repressor, to promoters containing E2F sites may permit inappropriate upregulation of factors governing S phase entry.34,35 Several groups have also shown that Mdm2 promotes the proteasomal degradation of pRb, although whether this outcome is dependent on the ability of Mdm2 to ubiquitinate pRb is not clear.32,36,37 Other studies have suggested that Mdm2 controls the intracellular level of the E2F1-DP1 complex, perhaps by regulating binding of E2F1 to the SCFSkp2 E3 ubiquitin ligase, so as to maintain levels below threshold that would otherwise trigger E2F1-dependent apoptosis in p53-null cells yet high enough to promote S phase entry.30,31 Mdm2 may thus perturb the cellular response to oncogenic stress, for example, by optimizing levels of E2F1 and promoting a pro-survival, antiapoptotic response to this protein.

Mdm2 has since been shown to influence the level or function of several other proteins involved in cell cycle control and apoptosis independent of its effects on p53. For example, Mdm2 promotes the ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation of the FOXO family of transcription factors, which regulate p27, cyclin D1, TRAIL, and other genes involved in cell proliferation and survival.38 In addition, the ability of Mdm2 to selectively ubiqutinate Erk-phosphorylated FOXO3a suggests that Mdm2 overexpression may cooperate with activated mitogenic signaling cascades to promote tumorigenesis. Mdm2 can also interact with the IRES on the 5′-UTR of the mRNA encoding the antiapoptotic protein XIAP.39 By enhancing the translation of XIAP, Mdm2 overexpression may blunt the apoptotic response to DNA damage and confer radioresistance.39 Finally, Mdm2 can bind to and impair the function of Nbs1, a critical mediator of the DNA double-strand break repair response, delaying the resolution of DNA lesions and promoting genomic instability.40

Mdm2 and Cancer: A Prognostic and Therapeutic Opportunity Leaps from Past to Present

Although several efforts have been made to correlate Mdm2 status with clinical outcomes in human cancers, the role of Mdm2 in sarcomas has been of particular interest. MDM2 amplification was originally demonstrated to occur in over one-third of human sarcomas, and these tumors were perhaps not surprisingly noted be more frequent in the Mdm2 transgenic mouse.24,41-43 Interestingly, human tumor samples were found to harbor either MDM2 amplification or loss of p53, but not both. The authors concluded that amplification of MDM2 and subsequent Mdm2 overexpression represented an alternative but functionally synonymous means of p53 inactivation that might otherwise be seen in the setting of p53 loss. Of clinical interest, a separate study detected MDM2 amplification among either metastatic or recurrent osteosarcoma but not in any primary tumors analyzed.44 Copy number alterations of MDM2, defined as the presence of greater than 3 copies of MDM2 in more than 10% of cells, have also been associated with poor response to chemotherapy in a larger study.45 These and others reports suggest that high Mdm2 expression is a poor prognostic indicator in osteosarcoma.

Studies of Mdm2 in human tumors have been extended to other malignancies, but these reports have undercut the mutually exclusive relationship between MDM2 amplification and p53 mutation.41,46-48 A unifying theme has been that Mdm2 overexpression need not occur exclusively in the setting of MDM2 amplification and that gene amplification does not necessarily result in detectable Mdm2 overexpression. For example, Watanabe et al.47 failed to detect MDM2 amplifications in any of 17 B-cell leukemias or lymphomas that had greater than 10-fold overexpression of Mdm2 by Northern blotting and immunohistochemical staining (IHC). Cordon-Cardo et al.46 noted that 5 of 11 soft tissue sarcomas with MDM2 amplification had IHC-undetectable Mdm2, whereas 17 of 62 sarcomas negative for MDM2 amplification were positive for Mdm2 by IHC.

Taken together, studies addressing Mdm2 in human tumors present contradictory clinical implications of its overexpression across a broad spectrum of malignancies.48 One concern is the use of IHC to detect either Mdm2 or p53, particularly due to the use of different antibodies to Mdm2. Total Mdm2 protein levels assessed in this manner may not account for mutant or alternatively or aberrantly spliced Mdm2. Attempts to assign a prognostic value to Mdm2 overexpression alone and in the setting of p53 mutation are also complicated by this approach. The use of elevated protein levels of p53 as a surrogate marker of p53 mutation that has lead to loss of function does not account for potential gain-of-function effects of certain p53 mutations.49 In addition, the functional equivalence of Mdm2 overexpression and loss of p53 need to be more thoroughly investigated. For example, even abnormally high levels of Mdm2 may abrogate p53 activity under basal conditions but should nevertheless be disengaged under genotoxic stress. The dynamic interplay between Mdm2 and p53 makes it difficult to accommodate a model of tumorigenesis in which Mdm2 inactivates the p53 pathway solely by virtue of its overexpression. It seems more plausible that there are effects of Mdm2 overexpression that do not mimic loss of p53. Indeed, the many p53-independent functions of Mdm2 speak to the need to consider that these separate lesions do not represent comparable pathways of p53 inactivation.

It has been proposed that therapies targeting the interaction between Mdm2 and p53 represent a possible means of pharmacologically reactivating the p53 pathway, and a number of such agents are currently in clinical trials.50,51 A more thorough understanding of the consequences of Mdm2 overexpression, particularly those that are independent of its roles as a regulator of p53, will greatly inform this therapeutic strategy.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Cahilly-Snyder L, Yang-Feng T, Francke U, George DL. Molecular analysis and chromosomal mapping of amplified genes isolated from a transformed mouse 3T3 cell line. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1987;13(3):235-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fakharzadeh SS, Trusko SP, George DL. Tumorigenic potential associated with enhanced expression of a gene that is amplified in a mouse tumor cell line. Embo J. 1991;10(6):1565-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finlay CA. The mdm-2 oncogene can overcome wild-type p53 suppression of transformed cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(1):301-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Momand J, Zambetti GP, Olson DC, George D, Levine AJ. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69(7):1237-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen J, Wu X, Lin J, Levine AJ. mdm-2 inhibits the G1 arrest and apoptosis functions of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(5):2445-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387(6630):296-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387(6630):299-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 1997;420(1):25-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marine JC, Dyer MA, Jochemsen AG. MDMX: from bench to bedside. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 3):371-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wade M, Wang YV, Wahl GM. The p53 orchestra: Mdm2 and Mdmx set the tone. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(5):299-309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kruse JP, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell. 2009;137(4):609-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sherr CJ. Divorcing ARF and p53: an unsettled case. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):663-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang Y, Lu H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(5): 369-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barak Y, Juven T, Haffner R, Oren M. Mdm2 expression is induced by wild type p53 activity. Embo J. 1993;12(2):461-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gajjar M, Candeias MM, Malbert-Colas L, et al. The p53 mRNA-Mdm2 interaction controls Mdm2 nuclear trafficking and is required for p53 activation following DNA damage. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(1):25-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Candeias MM, Malbert-Colas L, Powell DJ, et al. P53 mRNA controls p53 activity by managing Mdm2 functions. Nat Cell Biol. 2008; 10(9):1098-105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Montes de Oca Luna R, Wagner DS, Lozano G. Rescue of early embryonic lethality in mdm2-deficient mice by deletion of p53. Nature. 1995;378(6553):203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones SN, Roe AE, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Rescue of embryonic lethality in Mdm2-deficient mice by absence of p53. Nature. 1995;378(6553):206-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brown DR, Thomas CA, Deb SP. The human oncoprotein MDM2 arrests the cell cycle: elimination of its cell-cycle-inhibitory function induces tumorigenesis. Embo J. 1998;17(9):2513-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schlott T, Reimer S, Jahns A, et al. Point mutations and nucleotide insertions in the MDM2 zinc finger structure of human tumours. J Pathol. 1997;182(1):54-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Oca Luna RM, Tabor AD, Eberspaecher H, et al. The organization and expression of the mdm2 gene. Genomics. 1996;33(3):352-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bartel F, Taubert H, Harris LC. Alternative and aberrant splicing of MDM2 mRNA in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(1):9-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dang J, Kuo ML, Eischen CM, Stepanova L, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. The RING domain of Mdm2 can inhibit cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2002;62(4):1222-30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jones SN, Hancock AR, Vogel H, Donehower LA, Bradley A. Overexpression of Mdm2 in mice reveals a p53-independent role for Mdm2 in tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(26):15608-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McDonnell TJ, Montes de Oca Luna R, Cho S, Amelse LL, Chavez-Reyes A, Lozano G. Loss of one but not two mdm2 null alleles alters the tumour spectrum in p53 null mice. J Pathol. 1999;188(3):322-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lundgren K, Montes de Oca Luna R, McNeill YB, et al. Targeted expression of MDM2 uncouples S phase from mitosis and inhibits mammary gland development independent of p53. Genes Dev. 1997;11(6):714-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reinke V, Bortner DM, Amelse LL, et al. Overproduction of MDM2 in vivo disrupts S phase independent of E2F1. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10(3):147-54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martin K, Trouche D, Hagemeier C, Sorensen TS, La Thangue NB, Kouzarides T. Stimulation of E2F1/DP1 transcriptional activity by MDM2 oncoprotein. Nature. 1995;375(6533):691-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xiao ZX, Chen J, Levine AJ, et al. Interaction between the retinoblastoma protein and the oncoprotein MDM2. Nature. 1995;375(6533):694-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Loughran O, La Thangue NB. Apoptotic and growth-promoting activity of E2F modulated by MDM2. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(6):2186-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang Z, Wang H, Li M, Rayburn ER, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Stabilization of E2F1 protein by MDM2 through the E2F1 ubiquitination pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24(48):7238-47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sdek P, Ying H, Chang DL, et al. MDM2 promotes proteasome-dependent ubiquitin-independent degradation of retinoblastoma protein. Mol Cell. 2005;20(5):699-708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sdek P, Ying H, Zheng H, et al. The central acidic domain of MDM2 is critical in inhibition of retinoblastoma-mediated suppression of E2F and cell growth. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(51):53317-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stevaux O, Dyson NJ. A revised picture of the E2F transcriptional network and RB function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14(6):684-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu L. Tumour suppressor retinoblastoma protein Rb: a transcriptional regulator. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(16):2415-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miwa S, Uchida C, Kitagawa K, et al. Mdm2-mediated pRB downregulation is involved in carcinogenesis in a p53-independent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340(1):54-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uchida C, Miwa S, Kitagawa K, et al. Enhanced Mdm2 activity inhibits pRB function via ubiquitin-dependent degradation. EMBO J. 2005;24(1):160-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fu W, Ma Q, Chen L, et al. MDM2 acts downstream of p53 as an E3 ligase to promote FOXO ubiquitination and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(21):13987-4000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gu L, Zhu N, Zhang H, Durden DL, Feng Y, Zhou M. Regulation of XIAP translation and induction by MDM2 following irradiation. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(5):363-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bouska A, Eischen CM. Mdm2 affects genome stability independent of p53. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):1697-701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Momand J, Jung D, Wilczynski S, Niland J. The MDM2 gene amplification database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(15):3453-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oliner JD, Kinzler KW, Meltzer PS, George DL, Vogelstein B. Amplification of a gene encoding a p53-associated protein in human sarcomas. Nature. 1992;358(6381):80-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Leach FS, Tokino T, Meltzer P, et al. p53 Mutation and MDM2 amplification in human soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53(10, Suppl):2231-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ladanyi M, Cha C, Lewis R, Jhanwar SC, Huvos AG, Healey JH. MDM2 gene amplification in metastatic osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1993;53(1):16-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Duhamel LA, Ye H, Halai D, et al. Frequency of Mouse Double Minute 2 (MDM2) and Mouse Double Minute 4 (MDM4) amplification in parosteal and conventional osteosarcoma subtypes. Histopathology. 2012;60(2):357-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cordon-Cardo C, Latres E, Drobnjak M, et al. Molecular abnormalities of mdm2 and p53 genes in adult soft tissue sarcomas. Cancer Res. 1994;54(3):794-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Watanabe T, Hotta T, Ichikawa A, et al. The MDM2 oncogene overexpression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and low-grade lymphoma of B-cell origin. Blood. 1994;84(9):3158-65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rayburn E, Zhang R, He J, Wang H. MDM2 and human malignancies: expression, clinical pathology, prognostic markers, and implications for chemotherapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5(1):27-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Goh AM, Coffill CR, Lane DP. The role of mutant p53 in human cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223(2): 116-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Millard M, Pathania D, Grande F, Xu S, Neamati N. Small-molecule inhibitors of p53-MDM2 interaction: the 2006-2010 update. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(6):536-59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vu BT, Vassilev L. Small-molecule inhibitors of the p53-MDM2 interaction. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;348:151-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]