Abstract

Although strong evidence supports cognitive-behavioral therapy for late-life depression and depression in racial and ethnic minorities, there are no empirical studies on the treatment of depression in older sexual minorities. Three distinct literatures were tapped to create a depression treatment protocol for an older gay male. Interventions were deduced from the late-life depression literature, culturally adapted CBT protocols for racial minorities, and the emerging social and developmental psychological theories for lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Specific treatment interventions, processes, and outcomes are described to illustrate how these literatures may be used to provide more culturally appropriate and effective health care for the growing, older sexual minority population.

Although much attention has been given to the aging baby boomers and their related health care needs (Knickman & Snell, 2002), comparatively little attention has been directed toward aging sexual minorities. While lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals will face aging issues similar to the larger population, they may have important special mental health needs that necessitate tailored treatment adaptations. An estimated 1 to 2.8 million Americans over the age of 60 are lesbian, gay, or bisexual, a number that is expected to grow to 2 to 6 million by the year 2030 (Cahill, South, & Spade, 2000). Improving the treatment of late-life depression in general is a well-recognized priority within mental health (Charney et al., 2003), and given that LGB individuals of all ages may be at greater risk for developing psychopathology (Sandfort de Graaf, Bijl, Schnabel, 2001), developing tailored treatment approaches in this population is all the more critical.

This paper presents an example of cognitive-behavioral therapy adapted for a depressed, older gay male with complex medical co-morbidities and numerous psychosocial stressors. Currently, there are no published data on the prevalence of depression among older LGB adults. Similarly, there are no evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of depression among LGB adults. There is a robust epidemiologic and clinical literature available for depression in older adults and a modest literature for depression in ethnic minority populations (Miranda et al., 2005). There is also a growing social and developmental psychology literature on factors influencing mental health and well-being in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. We present a synthesis of these three important literatures and describe how they were used in the conceptualization and treatment of an older gay male with depression. Although many of the treatment adaptations and exercises described may be generalizable to lesbians and bisexuals, it is important to appreciate the heterogeneity and potentially different needs of others in the broad “LGB”category. Given the dearth of literature and the additional complexities of transgender mental health and societal stigma, specific transgender issues are not covered.

Depression in Older Adults

The lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder among adults aged 60 and older is estimated at 11%, and projected lifetime risk by age 75 is 23% (Kessler et al., 2005). The point prevalence of major depressive disorder among community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older is estimated at 1% to 4% (Cole & Yaffe, 1996; Mojtabai & Olfson, 2004; Steffens et al., 1999), with rates of subsyndromal, clinically significant depression estimated at 8% to 16% (Blazer, 2003). Prevalence rates of major depression and depressive symptoms are higher in samples of older adults in primary care, hospitalized for medical illness, or residing in long-term care facilities (Blazer, 2003). Although older adults are less likely to access and receive adequate mental health care services compared to middle-aged adults (Klap, Unroe, & Unützer, 2003), empirical data strongly indicate that late-life depression is highly treatable with appropriate psychosocial and pharmacological interventions (Mottram, Wilson, & Strobl, 2006; Pinquart, Duberstein, & Lyness, 2007).

Both antidepressant medications and psychotherapy are recommended as first-line treatments for depression in older adults (American Psychiatric Association, 2004; Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health, 2006). Generally, the forms of psychotherapy that are effective for the treatment of depression in younger adults are also effective for older adults. Cognitive-behavioral therapies, in particular, are well-supported. Using the criteria for evidence-based treatments established by Division 12 of the American Psychological Association, several forms of psychotherapy for late-life depression have been judged beneficial (Mackin & Areán, 2005; Scogin et al., 2005): behavioral therapy (BT), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive bibliotherapy, problem-solving therapy (PST), brief psychodynamic therapy (BDT), reminiscence therapy (RT), and interpersonal therapy (IPT) in combination with antidepressant medication. A recent meta-analysis of the effects of 57 controlled psychotherapy intervention trials for depressed older adults indicated large effect sizes for CBT and reminiscence therapy and medium effect sizes for psychodynamic therapy, psychoeducation, physical exercise and supportive therapy (Pinquart et al., 2007).

Although the general principles of CBT for depression appear to be similar in younger and older adults, various guidelines address the particular needs and circumstances of older adults. The Context, Cohort-Based, Maturity, Special Challenges model (CCMSC) is a transtheoretical model for adapting psychotherapy for older adults (Knight & McCallum, 1998). According to this model, providing effective psychotherapy to older adults depends on an understanding of the systems and communities that may (for better or worse) impact physical, economic, and social integrity (Context; e.g., age-segregated housing, Medicare regulations). Moreover, the particular set of political and cultural influences that have affected their generation’s values and abilities must be considered (Cohort-Based; e.g., earlier-born cohorts tend to have fewer years of formal education). Therapists must also consider that older persons’ greater wealth of life experiences afford them increased crystallized intelligence and the capacity for greater emotional complexity (Maturity) as they undertake some of the most difficult challenges of adult life (Special Challenges; e.g., caregiving, more losses).

The recommendations outlined in the CCMSC model are compatible with data on the factors that mediate CBT treatment outcomes in older adults. Among younger adults, reductions in depressive symptoms during the course of CBT are mediated in part by changes in dysfunctional and depressogenic attitudes (e.g., perfectionism, need for approval). Among older adults, however, reductions in depressive symptoms following treatment appear to be mediated by reductions in hopelessness and pessimism rather than changes in dysfunctional attitudes (Floyd & Scogin, 1998). In fact, older adults endorsed fewer dysfunctional attitudes than younger adults and those endorsed were less amenable to change with psychotherapy.

According to Floyd and Scogin, hopelessness may be particularly salient among older adults with depression because of the greater number of obstacles beyond individual control in late life (i.e., Special Challenges; such as illness, disability, forced relocation to long-term care). In order to effectively address hopelessness early in treatment, CBT therapists must have a solid understanding of the ways in which individuals can realistically exert control on their present situation (i.e., Context; e.g., being aware of health care and social services available to older adults). It may be useful to focus less on modifying entrenched dysfunctional beliefs and instead aim to reactivate positive beliefs and coping strategies (Knight & Satre, 1999). Life review strategies may be used to reframe losses as challenges for which older adults possess ample coping resources (Maturity, according to the CCMSC model). Specific treatment adaptations from the CCMSC and similar models are summarized in Table 1 (Knight & McCallum, 1998; Knight & Satre, 1999).

Table 1.

Treatment Adaptations for Older Adults

| Understand current contextual stressors and impact on daily functioning – e.g., housing, medical care needs, ageism. |

| Be familiar with historical and cultural influences that shaped the values and preferences of that generation (e.g., educational opportunities, gender roles). |

| Present materials more slowly and use mnemonics (written aids) more regularly. |

| Allot time for reminiscence and expect therapy to include both past and present foci. |

| Capitalize on greater, richer life experiences and potential mastery and/or reactivation of successful coping skills learned in the past. |

| Utilize older adults’ greater emotional complexity and encourage elaboration (or reactivation) of positive states and beliefs intermingled with negative feelings and beliefs. |

| Utilize more abstract cognitive interventions to tap older adults’ greater capacity to draw generalizations across the life span and different circumstances. |

Depression in Racial Minority Populations

In general, rates of mental illness in ethnic and racial minority populations are equivalent to or lower than rates in whites. However, some studies suggest that minorities are less likely to be diagnosed or referred for appropriate treatment (Borowsky et al., 2000; Gallo, Bogner, Morales, & Ford, 2005; Miranda, McGuire, Williams, & Wang, 2008). For those minorities who are referred, they may receive lower quality or inappropriate care, and are more likely to drop out (Miranda & Cooper, 2004; U.S. DHHS, 2001). Additional factors that might account for depression and other psychopathology in this population include prejudice and mistreatment associated with minority status, acculturative stress, and complex social-contextual factors such as greater risk of exposure to violence, abuse, parenting style, and substance use (US DHHS, 2001). Furthermore, although some Asian Americans have equal or higher incomes than whites, minority status is typically associated with lower socio-economic status—a well-established risk factor for psychopathology (Holzer et al., 1986; Muntaner, Eaton, Diala, Kessler, & Sorlie, 1998; Regier et al., 1993; US DHHS, 2001).

Although few well-controlled and adequately powered trials of CBT adapted for minority populations exist, several small efficacy trials and larger effectiveness studies suggest that CBT is an effective treatment for depression with Latinos (Organista, Muñoz, & Gonzales, 1994), African-Americans (Kohn, Oden, Muñoz, Robinson, & Leavitt, 2002), and Asian-Americans (Dai et al., 1999). CBT in combination with case management or pharmacotherapy was also found to be effective in minority populations (Miranda, Chung, et al., 2003). Primary care quality-improvement projects that have included both CBT and medications have shown benefit to African-Americans and Latinos with depression (Wells et al., 2004). Data from effectiveness studies overwhelmingly show that evidence-based practices (EBPs) for the treatment of depression in older adults have comparable effects in minority and nonminority populations, provided minority populations are given access to care (Areán et al., 2005).

As a means of providing more appropriate and effective care for special populations, appeals for “cultural competence” among health care providers, institutions, and systems of care have been issued (Sue, Zane, Nagayama-Hall, & Berger, in press). Culturally competent treatment adaptations can be broadly classified as pertaining to methods of delivery and content. Examples of delivery adaptations include where treatment is delivered, by whom, choice of treatments provided, pacing of sessions, and interpersonal style (e.g., respeto). Examples of content adaptations include providing materials in clients’ language of choice, specifically inquiring about acculturation and immigration issues, and including content that may be important to that particular group, such as spirituality or family relationships. The American Psychological Association offers broad clinical guidelines for working with diverse populations that include recommendations for tailoring treatment to individuals in the context of their respective cultures (American Psychological Association, 2003). The Psychotherapy Adaptation and Modification Framework (Hwang, 2006) provides a model of how to make culturally informed adjustments to evidence-based treatments. Large CBT trials comparing minority-adapted CBT to nonadapted CBT have not been completed; however, promising outcomes suggest that these adaptations might be beneficial (Kohn et al., 2002; Miranda, Azocar, Organista, Dwyer, & Areán, 2003; Muñoz & Mendelson, 2005; Satterfield, 1998). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis of cultural competence mental health care studies revealed a moderate effect size for treatment adaptations (Griner & Smith, 2006). Examples of specific treatment adaptations for ethnic and minority populations can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Treatment Adaptations for Racial and Ethnic Minorities

| Acquire knowledge about the history, cultural norms, immigration patterns, values, and beliefs about mental health/illness in the most commonly seen target populations. Use this information to shape case formulations and improve empathic accuracy. |

| Elicit primary aspects of identity and how those factors impact daily interactions, social relationships, professional functioning, and mental health. Include history of possible stigma, prejudice, “micro-aggressions,” and other discrimination. Utilize “dynamic sizing” – i.e. move fluidly between the use of generalizations and recognizing individuality. |

| Explicitly acknowledge potential differences between provider and patient. Express humility and interest in learning more about patient and his/her worldview. |

| Understand historical reasons for mistrust of health professionals. Do not assume membership in the same cultural group earns automatic trust (or nonmembership equals automatic distrust). Devote special attention to building trust over time and empowering the client. |

| Assess linguistic ability and literacy – adjust treatment and materials accordingly. Use appropriate language, terminology, metaphors, and other imagery that is familiar. |

| Adapt therapeutic style to better match expected cultural norms – e.g. “respeto,” “simpatia,” “personalismo.” |

| Include nonstandard content that might have high relevance to the target group – e.g. discussion of acculturative stress, immigration, spirituality, access to social services. |

| Broaden the definition of social support network and assist the patient in identifying key figures, their interrelationships, power hierarchy, and roles in decision-making. |

Depression and Mental Health in LGB Populations

Rates of depression in gay men and lesbians are higher than those in their heterosexual counterparts. Data analyzed from a national probability sample from the Netherlands indicated higher lifetime rates of major depression among homosexual men and women compared to heterosexual men and women (Sandfort et al., 2001). In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 25 studies, LGB people (transgender were not included) had a two-fold excess in suicide attempts and 1.5 times greater lifetime risk for depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders (King et al., 2008). Of course, these studies do not imply that homosexuality itself is pathological. Moreover, LGB epidemiological researchers chronically struggle with how to define this population and access a representative sample.

Risk factors or other etiological considerations for depression in this population, and especially the older LGB population, have not received sufficient empirical attention. Biological theories implicate gonatropic hormones, neuroanatomy and physiology, and prenatal androgens (Bailey, 1999; Mustanski, Chivers, & Bailey, 2002; Roper, 1996). Social factors such as societal stigma (Herek, 1991), daily “microagressions” related to minority stress (DiPlacido, 1998; Greene, 1994; Sue et al., 2007), and maladaptive coping responses such as drinking and substance abuse are also likely to contribute to this population’s burden of psychopathology (King et al., 2008). Although subtle and slow to build, the cumulative burden of being a stigmatized minority can have profound health effects through a process called “weathering” (Geronimus, Hicken, Keene, & Bound, 2006). In the National Survey of Midlife Development, LGB individuals report substantially more lifetime and day-to-day stressors with nearly half attributing the stress to sexual orientation. Those with higher stress levels reported lower quality of life and greater psychiatric morbidity (Mays & Cochran, 2001). From a behavioral perspective, deviation from traditional gender roles and exploration of nonheterosexual behavior are punished. From a social-learning perspective, negative models and broader societal messages teach fear and aversion of LGB persons who are perceived as a “threat” to marriage, families, and moral or religious values. For LGB persons, these chronic stressors are likely to shape negative thoughts about the self (e.g., internalized homophobia), the world (e.g., it is an unsafe, uncaring place), and the future (i.e., the negative cognitive triad). It has further been suggested that ageism or the “worship of youth” in gay male culture “accelerates” perceptions of aging among gay men and may powerfully impact thoughts about the self (e.g., unlovability, undesirability) and others (e.g., rejection of older persons) (Cahill et al., 2000).

In terms of social support, it is unclear if LGB individuals are at a disadvantage. Although experiences with bias-driven rejection, fears for personal safety, and/or the consequent shame from internalized homophobia may cause difficulty in finding and keeping social supports, the LGB community has become increasingly visible and powerful. Membership in this community may confer a sense of belonging and support (Frable, Wortman, & Joseph, 1997). Given the greater likelihood of familial rejection as a consequence of coming out or otherwise disappointing parental expectations, LGB persons are often forced to broaden their social networks and expand whom they consider to be family, creating a sort of fictive kin network (Laird & Green, 1996; Westin, 1992). Although many gays and lesbians do have children, many do not. Older LGB individuals may not have the support of children and grandchildren to help them as they age and become less independent. In fact, a disproportionate number of LGB elderly live alone (Cahill et al., 2000; Whitford, 1997). The convoy model of social relations predicts a curvilinear relationship between age and number of “close” and “very close” relationships. Empirical evidence supports the prediction that social network size peaks in midlife and declines in older age (Antonucci, Akiyama, & Takahashi, 2004). This may be in part due to older adults’ preference for maintaining familiar relations rather than seeking new ones (Carstensen, 1995). Although it is not clear how age interacts with sexual orientation in determining number of close relationships, it is reasonable to expect that older LGB persons’ “social convoys” may often be comprised of friends and other nonfamilial community members.

Older LGB patients may also face heightened medical, legal, and/or financial stressors. For example, same-sex partners in the United States are not eligible to receive widow or widowers’ social security benefits nor can they inherit a deceased partner’s 401K (i.e., retirement savings account in the United States) without a 20% federal withholding penalty. Special legal arrangements must be made to ensure hospital visitation rights and involvement in medical treatment planning. Health insurance coverage typically cannot be shared between same-sex partners depending on the state of residence (in the U.S.). Stigmatization and bias in health care providers against LGB patients is well-documented, resulting in wide disparities in preventive care, chronic disease management, and even emergency care (AMA Council on Scientific Affairs, 1996; Cahill et al., 2000).

Older generations may also have different experiences of historical events such as the civil rights or women’s rights movements, AIDS, or the more recent gay empowerment movements (Cahill et al., 2000). Older generations are more likely to have been married to an opposite sex partner at some earlier time and may have been diagnosed as mentally ill because of their sexuality (Frost, 1997; Herdt, Beeler, & Rawls, 1997; Kimmel, 1995; McDougal, 1993). As with their heterosexual counterparts, attitudes about dating, relationships, communication, and morality might differ notably from younger generations.

In contrast to these elevated risk and vulnerability factors, it is also possible that the developmental experiences required for reconciling a gay identity in a homophobic society might confer special strengths or advantages (Bieschke, Perez, & DeBord, 2006). LGB elders may have developed greater “crisis competence,” having navigated coming out, homophobia, HIV/AIDS, and other key events (Wahler & Gabbay, 1997). LGB elders are more likely to have successfully formed identities as sexual minorities and fully integrated these aspects into their lives and relationships. Moreover, LGB elders may be better equipped to cope with the stressors of ageism since they have already learned to cope with the stigma of being a sexual minority (Fassinger, 1997; Kimmel, 1995; Lee, 1990). Other theories suggest that gay men and lesbians have more flexible gender roles, earlier experiences with being independent, and those in the later stages of homosexual identity development (“synthesis” and “pride”) have greater psychological well-being (Bieschke et al., 2006; Halpin & Allen, 2004).

In recent decades, there has been a dramatic shift in the way LGB populations are viewed by the mental health profession. Homosexuality has moved from a form of sociopathy to a sexual deviance to a normal variant of healthy human sexual expression (APA, 2000; Bieschke et al., 2006; Green & Croom, 2000; Martell, Safren, & Prince, 2004; Martell, 2008). Moreover, there is a growing recognition of the special psychological needs specific to LGB persons. At present, national advocacy organizations have identified the unmet needs of this population and have published guidelines for psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients including those from the aging LGB community (American Psychological Association, 2000; see APA Division 44, Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Issues and the APA Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Concerns).

When caring for LGB patients, it is important to appreciate the range of meanings and feelings attached to membership in this community. Sexual orientation is but one facet of an individual’s core identity that may vary in its relative importance to other factors such as race, ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic status. Moreover, sexual orientation may play a central role in the development of psychopathology and its treatment or it may play no role at all (Martell, 2008; Purcell, Campos, & Perilla, 1996; Safren & Rogers, 2001). Additionally, the issue of how to define this community emerges. LGB individuals can be defined by recent or predominant sexual behavior (e.g., men who have sex with men), how an individual self-defines, or some combination of the two. For the purposes of this case study, LGB is based on patient self-identity—a construct that perhaps reflects a core construct of his internalized identity and level of openness. In addition to the generalizable recommendations in Tables 1–2, further recommendations for psychotherapy with LGB patients can be found in Table 3. Concrete examples of how treatment recommendations for older adults, racial/ethnic minorities, and LGB patients are applied to a specific case are described in the case of Mr. B below.

Table 3.

Treatment Adaptations for Sexual Minorities

| Sexuality should neither be overemphasized nor ignored. Explore whether sexuality plays a role in the presenting issue and needs to be addressed. |

| Appreciate the range of life experiences LGB clients may have had when coming to terms with their sexuality – e.g. coming out in a rural setting may vary greatly from coming out in an urban area. |

| If appropriate, assess the cumulative stress created from ongoing discrimination and stigma. Assess for past trauma and/or negative encounters with health care. |

| Broaden the definitions of family and social support. Allow the patient to identify his/her own family and the roles they play in daily life and decision-making. |

| Normalize potential internalized homophobia and how it may be temporarily reactivated in times of stress. Have client recall signature strengths and affirming aspects related to LGB identity. |

| Recognize that clients may possess “crisis competence,” or an ability to effectively cope with highly stressful situations, as a result of having navigated coming out, homophobia, HIV/AIDS, and other key events. |

| Do not assume that sexuality-related attributions for negative events are “distorted” or overly sensitive nor are they necessarily “true” – e.g. “She didn’t say hello to me because she hates lesbians.” Assist the patient in exploring constructive ways to think and behave in these scenarios. |

Case Example: Mr. B

Patient Identifying Information

Mr. B was a 61-year-old, single gay male self-referred for treatment of depression. Mr. B complained of “feeling overwhelmed and tired” and “wondering if I should just finally give up.” At the time of treatment, Mr. B had been HIV-positive for approximately 20 years and had recently been treated for bladder cancer.

History of Present Illness

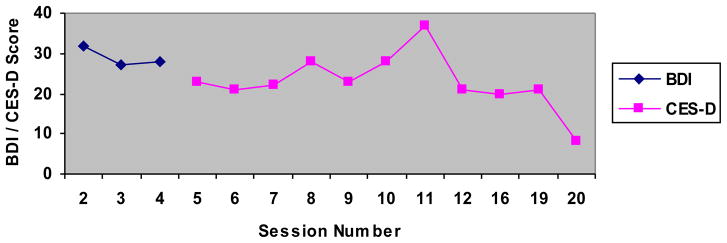

Mr. B reported “spiraling downward” for approximately 4 months after receiving a diagnosis of early-stage bladder cancer. After two successful surgeries and chemotherapy, he was given a 50% chance of recurrence. Mr. B’s medical recovery was complicated by a necessary change in his HIV medications that precipitated severe diarrhea and nausea. He reported low mood, anhedonia, early insomnia, weight loss, low energy, psychomotor retardation, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, and passive suicidal ideation. His initial score on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) indicated that his symptoms were in the severe range (see Figure 1). He also met criteria for dysthymia and had notable but subsyndromal generalized anxiety. Mr. B had a recurrence of bladder cancer near Session 10 that required additional chemotherapy and caused a brief exacerbation of his depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

BDI and CES-D Scores for Mr. B.

Past Medical and Psychiatric History

Mr. B was diagnosed with HIV in the late 1980s but believes he may have been infected earlier. He had several opportunistic infections and hospitalizations in the early 1990s but responded well to antiretrovirals in 1996. His viral load began to climb on three separate occasions, necessitating a change in his HIV medication regimen. He has subsequently developed lipodystrophy and moderate to severe peripheral neuropathy. In his early 50s, he was diagnosed with hypertension and developed a deep vein thrombosis requiring anticoagulation therapy. He was diagnosed with Stage 1 bladder cancer (transitional cell carcinoma) 4 months prior to mental health treatment. He maintained a complex regimen of HIV medications, statins, antihypertensives, anticonvulsants (for peripheral neuropathy), and opiates as needed for pain management. Mr. B believed that this was his third lifetime episode of major depression. Perhaps due to his medical comorbidities and complex medication regimen, he had not been able to tolerate antidepressants from various classes. He reported several brief courses of unspecified psychotherapy in the past that were helpful.

Social History

Mr. B was born and raised in a low-middle income, conservative, rural setting. Being gay was “not an option.” Although sexuality was rarely discussed, it was nearly always a source of great shame and condemnation: “I was a queer kid, and I’ve gotten lifelong messages, starting as early as I can recall, that big parts of me, even my core, had to be hidden if I was to be loved or survive. This takes a toll and taught me that the real me is unlovable and that the public me is false.” (It is notable that Mr. B referred to himself as “queer” rather than “gay.” When asked to distinguish the two, he described queer as a proud, unapologetic “proclamation” of sexuality versus the more “sterile, safe” term gay.) He graduated from college and worked as a teacher until going on disability in the early 1990s following several debilitating opportunistic infections. He supplemented his income doing errands and light housework for neighbors and acquaintances. At the time of treatment, he lived with a close female friend. Mr. B had several brief (1- to 2-year) romantic relationships but believed he was “just better on my own.” He had experienced multiple losses of close friends due to AIDS and was estranged from his conservative, Christian family. Mr. B had few social interactions and felt “out of place” in senior centers due to his sexuality and HIV status.

Case Conceptualization

Mr. B’s recent struggle with bladder cancer and its sequelae served as a precipitating event for his current depressive episode. His past history of major depression undoubtedly heightened his biologic and, perhaps, cognitive vulnerability to relapse. Core beliefs of unlovability and worthlessness tied to early experiences of homophobia were re-activated. Although Mr. B had successfully been living with HIV/AIDS for over a decade, his “crisis competence” skills were overwhelmed by rekindled fears of mortality, isolation, stigma, and rejection. Moreover, his age-related fears of physical dependence and financial strain were exacerbated by the increased disability caused by his bladder cancer. Over the course of his medical and mental health treatment, core identity issues and their impact on interpersonal dynamics emerged. Mr. B worried about potential bias against him as a gay man, a long-term HIV survivor, and/or bias related to his age. He temporarily found assertiveness with his medical providers to be quite difficult given his “regressed,” hypersensitive state as a “sissy” in a world of stronger (straight) men. His struggles with health insurance companies activated memories and beliefs about being an underrepresented, disenfranchised minority that needed to “rage” in order to be heard. As Mr. B fought his “growing despair” regarding the burden of medical disease, he was reminded of the losses of multiple friends to AIDS and his fears of dying alone. Treatment goals included the reactivation of successful coping (and grieving) skills, reminiscence of stressors successfully managed (including coming out, HIV/AIDS), and elicitation of more positive states while acknowledging the complex challenges of his day-to-day life.

Course of Treatment and Therapeutic Interventions

Mr. B attended 20 individual cognitive-behavioral therapy sessions over the course of 1 year. Sessions 1–12 occurred weekly and sessions 13–20 were gradually tapered down in frequency. Progress was initially measured with the BDI but was switched to the CES-D after Session 4 (measure switched per patient request; see Figure 1). Daily mood, sleep, and energy were monitored as needed. All sessions were tape recorded so Mr. B could review CBT materials on his own.

After the initial intake assessment, treatment began with a discussion of Mr. B’s goals, a description of CBT, and psychoeducation regarding depression. In addition to alleviating his depressive symptoms, Mr. B hoped to find better ways to cope with his fears regarding bladder cancer and having HIV as an older gay man. Mr. B was referred to the Feeling Good Handbook (Burns, 1999) for further information regarding CBT for depression, and Minding the Body (Satterfield, 2008b) for more specific information regarding CBT and coping with serious chronic illness. Both interventions and processes were shaped based on treatment adaptations recommended for older adults, minorities, and LGB populations. As treatment progressed, Mr. B was encouraged to select and adapt his own interventions based on self-assessments of skill and residual symptoms. Examples of interventions are described below.

Activity record and scheduling

Mr. B began self-monitoring his activities and daily mood to identify mood “lifters” and “downers.” After a review of his initial activity records, it was clear that his medical comorbidities and mobility problems greatly limited both the quality and quantity of activities that could be used for behavioral activation. Moreover, Mr. B’s identity as “openly queer” potentially limited his participation in senior centers and other social groups targeting his age group or medical condition. This “context” specific information as recommended by the CCMSC model was essential in shaping later behavioral activation strategies (Knight & McCallum, 1998).

The initial challenge was to disentangle depression-related fatigue and inertia with HIV and/or cancer-related fatigue. Mr. B vacillated between “I have to push myself to get off my duff and be more active” to “I’m ill and really should take it easy.” After initial conversations with his oncologist and HIV physician, Mr. B developed a daily energy scale that assessed “physical energy” and “energy of the spirit” with the goal of distinguishing when he was tired due to medical causes (“physical energy”) versus tired due to feeling depressed (“energy of the spirit”). During times of low physical energy, Mr. B would select enjoyable but more sedentary activities such as reading or listening to music. During times of low energy of the spirit, he would select more physically demanding activities such as walking his dog or window shopping. Mr. B eventually created 3 activity lists (physical, spirit, and “little things”) that included pleasant and mastery activities. “Little things” were intended for times of low physical and low spirit energy (e.g., splash cool water on face, smell roses, stretch, look at photos, count my blessings, reminisce). The process of helping Mr. B to select activities that were both achievable and adaptable according to his level of energy served to combat his hopelessness that there was little he could do to improve his situation.

Building social supports

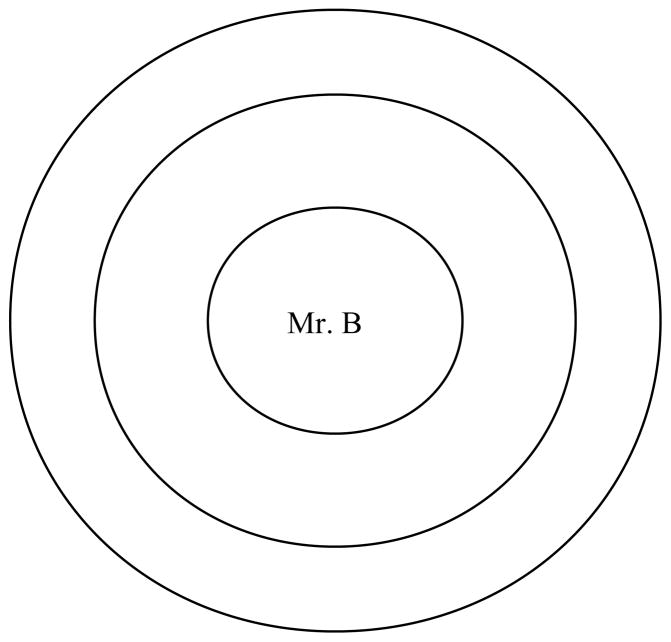

Mr. B had lost almost his entire friendship network to AIDS. He lived with one female friend and had one close childhood friend who lived several hundred miles away. He felt stymied in building new social supports due to his health, age, and sexuality. An in-depth social support assessment was used to assess the need for new supports, the need to build greater intimacy with existing supports, and any deficiencies in particular types of support (e.g., emotional, practical, or informational support; see Figure 2; adapted from Satterfield, 2008a). Mr. B’s responses to this exercise identified key supports, the degree(s) of intimacy, and the types of support he had readily available. Mr. B agreed that he needed to add new people to the diagram and try to pull more distant friends into his “inner circle.” Subsequent interventions included assisting Mr. B in better identifying his support needs and which individuals could provide what type of support (Chesney et al., 2003). Although efforts to improve intimacy with existing supports were successful, new additions to his social support network proved more difficult. Although appropriate social groups and activities were identified, Mr. B’s homophobia-influenced self-concept regarding his lovability and value initially served as potent inhibitors. However, to some degree this outcome may also be consistent with socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1995), which predicts that as people age they become more selective in forming attachments, especially in times of emotional uncertainty.

Figure 2.

Social Support Assessment Tool. Instructions to patient: Write in the names of individuals who are part of your social support network. Place each name closer or further away from the center depending on how close you are to that person. Adapted from A Cognitive Behavioral Approach to the Beginning of the End of Life: Minding the Body (p. xx), by J. M. Satterfield, 2008, New York: Oxford University Press.

Cognitive interventions

Thought records were initially used to demonstrate the relationship between mood and cognition. As in standard cognitive therapy, Mr. B began with capturing automatic thoughts about current situations and “rewriting” those thoughts into more helpful formats. Mr. B learned basic cognitive skills such as reframing (e.g., seeing stressors as challenges), cognitive restructuring, semantic analysis (e.g., “What does it mean when I say I am a failure? What is a failure? What is my criteria for success?”), examination of biases, searching for evidence, and “downward arrow.” Common automatic thoughts included, “I have lived my life all wrong,” “Being queer makes me a bad person,” and “I have AIDS because my lifestyle deserves punishment.” It is important to note that although Mr. B’s explicit ideology included being accepting or even proud of being gay, his implicit homophobic biases were made manifest in times of depression and vulnerability. In this regard, the injury was twofold—first, from the negative impact of the thoughts, and second, from the shame of having had those thoughts when he believed he had moved far beyond “closet-case insecurities.”

As a result of his frequent, self-assigned cognitive exercises (two to three thought records per day), Mr. B was able to quickly move beyond situational automatic thoughts and challenges. As themes in his automatic thoughts began to emerge, Mr. B constructed a set of conditional assumptions and core beliefs—many of which were closely linked to his age, health status, and sexuality. He often noted that although he “knew” these beliefs were untrue, he “felt” them nonetheless. He called them his “bedrock of self-hate” where “life poured the cement but homophobia hardened it.” Examples of conditional assumptions and core beliefs are found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Sample Cognitive Content for Mr. B

| Conditional Assumptions | Core/Intermediate Beliefs |

|---|---|

| If people know I am gay (or HIV positive), then I will be shunned. | I am an unlovable, fundamentally damaged person (because I am gay). |

| If bad things happen to me (cancer, HIV), then I must have deserved it. | I have lived my life all wrong (as an openly gay man). |

| If I am struggling to get by, then I must have screwed up my life. | I’m a complete failure as a son, friend, significant other, worker, human. |

| If I’m over 60, then I’m seen as useless to society – just a burden. | I’m fragile and weak (due to age, health, sexuality). |

| If you don’t have children or grandchildren, then you cannot be happy in old age. | I’m doomed to die alone. |

Mr. B began “chipping away at my bedrock of self-hate” by using a combination of core beliefs worksheets and affirmative evaluations of sexuality and age. His analyses from these exercises were used to create a series of “mantras.” These mantras were essentially short catch-phrases that stood for voluminous arguments and evidence supporting his lovability and life successes. Whenever a well-worn core belief or assumption was environmentally triggered, the mantra was used as a sort of thought-stopping, mnemonic tool that reminded Mr. B of the fallacies of his societally inherited homophobia and ageism. Examples of mantras include, “Kindness above all else,” “Life is short so maximize the good,” “This too shall pass,” “Dorothy will never surrender!,” “This is an inconvenience, not a crisis,” “Life is seldom a cabaret, but when it is, belly up to the bar!” and “Appreciate flawfulness.” In accordance with the CCMSC model of treatment adaptations for older adults, one important aspect of cognitive restructuring with Mr. B was drawing on his earlier experiences of developing positive self-beliefs with respect to his sexuality. In partial contrast to earlier work with older adults (Floyd & Scogin, 1998), Mr. B found it helpful to challenge both dysfunctional attitudes and hopelessness cognitions in addition to positive reframing and life review. The direction of his ongoing cognitive work was primarily determined by his own self-assessments of effectiveness and value.

Given Mr. B’s additional goals of coping more effectively with his cancer and HIV, further cognitive interventions to address these issues were developed. Mr. B began to identify and then restructure his explanatory models of illness for both HIV and cancer (Kleinman, 1989). His initial models included strong aspects of self-blame (“I deserve this/I caused this”), hopelessness, and passivity in dealing with his medical providers. He was uncertain about his ability to step forward and become an active participant in the management of his chronic diseases. By shifting blame from a purely internal locus, he was able to adopt a less punitive and more balanced attribution about why he was ill. These new attributions allowed him to “fight for the top notch treatment I deserve” and minimize the additional emotional damage caused by self-blame and hopelessness. In-session exercises also included assertiveness training. For example, Mr. B was prescribed a medication that he knew gave him severe GI side effects but failed to say anything at the time to his doctor. He practiced ways to respectfully but assertively remind his physician that he had been on that medication before and could not tolerate it. Mr. B described his efforts to speak more assertively as trying to “find the voice of a sissy-boy” when confronting powerful male authority figures like his oncologist (although now an educated and capable adult, at times he still felt like a timid, fearful, effeminate child who needed to learn how to speak up). Additional interventions included creating a pain management plan, listing concrete strategies to cope with medication side effects, promotion of medication adherence, and a discussion of the “business” of preparing for end-of-life (e.g., durable power of attorney, DNR/DNI orders, creating a legacy project; Satterfield, 2008). In addition to building social supports with individuals, Mr. B began exploring ways to feel connected to a higher power. His “going to church” included being in nature and feeling part of a harmonious whole.

As mentioned earlier, Mr. B had a recurrence of bladder cancer just after Session 10 of 20. At this point in treatment, Mr. B had well-developed behavioral activation skills, good daily thought record skills, and was working to develop his mantras and build his social support network. This medical event triggered a temporary spike in his CES-D scores. His automatic thoughts included, “I can’t go through this again,” “This is the end, I’ll never survive,” “No one will be there to help me recover after surgery.” Mr. B eventually reframed this event as a real-world test of his newly acquired CBT skills. He successfully contacted and rallied his social supports and did multiple pages of thought-records to promote more constructive coping. He was able to reframe his prior AIDS-related “brushes with death” as evidence of his capacity to cope, heal, and emerge psychologically stronger than before. He had a quick recovery from an additional surgery and a light course of chemotherapy. His CES-D scores continued to decline until his lowest score of 8 on Session 20.

Discussion and Conclusion

The substantive literatures on late-life depression, minority depression, and LGB psychology were used to deduce an individually tailored treatment program for an older gay man. Despite multiple medical comorbidities and substantial ongoing stressors, Mr. B was able to achieve a full recovery and remains in remission at this time. Although many of the interventions used were not specific to LGB populations, the special attention to social context, social history, and his identity may have improved treatment acceptability and amplified clinical impact.

The exact degree to which Mr. B’s treatment can be generalized to other older LGB patients is unclear. Although Mr. B had recurrent, severe depression with multiple, serious medical comorbidities, he was educated, motivated, and well-insured. For Mr. B, CBT essentially became his “day job” that included transcribing all therapy sessions, doing thought records, and working through CBT books on his own. Although other patients may not be as motivated or capable, many of the exercises and treatment adaptations remain relevant. It is important to note that although Mr. B had the additional stressor of a low income, he did not have to cope with misogyny or racism or transphobia. The cumulative burden carried by these populations is likely to be greater and might necessitate further treatment adaptations and sensitivity. As engagement and treatment of the older LGB community improves, it is hoped that their special similarities and differences to other populations will be noted, celebrated, and ultimately used to provide superior clinical care.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Medical Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Health care needs of gay men and lesbians in the United States. JAMA. 1996;275(17):1354–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. 2. 2004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist. 2000;55:1440–1451. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.55.12.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist. 2003;58:377–402. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.5.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Akiyama H, Takahashi K. Attachment and close relationships across the life span. Attachment and Human Development. 2004;6:353–370. doi: 10.1080/1461673042000303136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areán PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, Lin EHB, Linqi T, Harpole L, et al. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Medical Care. 2005;43:381–390. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey M. Homosexuality and mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:883–884. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieschke KJ, Perez RM, DeBord KA, editors. Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. 2. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. Depression in late life: Review and commentary. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences. 2003;58A:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DD. The feeling good handbook. New York: Plume Books; 1999. (Rev. ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, South K, Spade J. Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender elders. Washington, DC: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors’ Mental Health. National guidelines for seniors’ mental health: The assessment and treatment of depression. 2006 Retrieved April 7, 2008, from www.ccsmh.ca/en/guidelinesUsers.cfm.

- Carstensen LL. Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4:151–162. doi: 10.1177/09637214211011468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charney DS, Reynolds CF, Lewis L, Lebowitz BD, Sunderland T, Alexopoulos GS. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in late life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:664–672. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Johnson LM, Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: Results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:1038–46. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097344.78697.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MG, Yaffe MJ. Pathway to psychiatric care of the elderly with depression. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1996;11:157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Zhang S, Yamamoto J, Ao M, Belin TR, Cheung F, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy of minor depressive symptoms in elderly Chinese Americans: A pilot study. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35:537–542. doi: 10.1023/a:1018763302198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPlacido J. Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia, and stigmatization. In: Herek G, editor. Psychological perspectives on lesbian and gay issues: Vol, 4. Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexual…. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 138–159. [Google Scholar]

- Fassinger R. Issues in group work with older lesbians. Group. 1997;21:191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd M, Scogin F. Cognitive-behavior therapy for older adults: How does it work? Psychotherapy. 1998;35:459–463. [Google Scholar]

- Frable DES, Wortman C, Joseph J. Predicting self-esteem, well-being, and distress in a cohort of gay men: The importance of cultural stigma, personal visibility, community networks, and positive identity. Journal of Personality. 1997;65:599–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost J. Group psychotherapy with the gay male: Treatment of choice. Group. 1997;21:267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Morales KH, Ford DE. Patient ethnicity and the identification and active management of depression in late life. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165:1962–1968. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:826–833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green B, Croom GC, editors. Education, research, and practice in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered psychology: A resource manual. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greene B. Ethnic minority lesbians and gay men: Mental health and treatment issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:243–251. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43:531–48. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpin SA, Allen MW. Changes in psychosocial well-being during stages of gay identity development. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47:109–126. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, Beeler J, Rawls TW. Life course diversity among old lesbians and gay men: A study in Chicago. Journal of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity. 1997;2:231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Herek G. Stigma, prejudice, and violence against lesbians and gay men. In: Gonsiorek J, Weinrich J, editors. Homosexuality: Research implications for public policy. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. pp. 60–80. [Google Scholar]

- Holzer C, Shea B, Swanson J, Leaf P, Myers J, George L, et al. The increased risk for specific psychiatric disorders among persons of low socioeconomic status. American Journal of Social Psychiatry. 1986;6:259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W. The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: Application to Asian Americans. American Psychologist. 2006;61:702–715. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel D. Lesbians and gay men also grow old. In: Bond L, Cutler S, Grams A, editors. Promoting successful and productive aging. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klap R, Unroe K, Unützer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: A focus on older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A. The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books; 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickman JR, Snell EK. The 2030 problem: Caring for aging baby boomers. Health Services Research. 2002;37(4):849–884. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, McCallum TJ. Adapting psychotherapeutic practice for older clients: Implications of the contextual, cohort-based, maturity, specific challenge model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1998;29:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, Satre D. Cognitive behavioral psychotherapy with older adults. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:188–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn LP, Oden T, Munoz RF, Robinson A, Leavitt D. Adapted cognitive behavioral group therapy for depressed low income African American women. Community Mental Health Journal. 2002;38:497–504. doi: 10.1023/a:1020884202677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird J, Green RJ. Lesbians and gays in couples and families: Central issues. In: Laird J, Green RJ, editors. Lesbians and gays in couples and families: A handbook for therapists. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JA. Gay midlife and maturity. New York: Haworth Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mackin RS, Arean PA. Evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions for geriatric depression. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;28:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Safren S, Prince SE. Cognitive-behavioral therapies with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual women and men. In: Whisman MA, editor. Adapting cognitive therapy for depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal G. Therapeutic issues with gay and lesbian elders. Clinical Gerontologist. 1993;14:45–57. doi: 10.1300/j018v14n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista K, Dwyer E, Arean P. Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups disadvantaged medical patients. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:219–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, Kohn L, Hwang W, LaFramboise T. State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:113–142. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, Krupnick J, Siddique J, Revicki DA, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Cooper LA. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, McGuire TG, Williams DR, Wang P. Mental health in the context of health disparities. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1102–1108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Wells K. Effects of primary care depression treatment on minority patients’ clinical status and employment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:827–834. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Major depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: Prevalence and 2- and 4-year follow-up symptoms. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:623–634. doi: 10.1017/S0033291703001764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottram P, Wilson K, Strobl J. Antidepressants for depressed elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;4:CD003491. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003491.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz RF, Mendelson T. Toward evidence-based interventions for diverse populations: The San Francisco General Hospital prevention and treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:790–799. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Diala C, Kessler RC, Sorlie PD. Social class, assets, organizational control and the prevalence of common groups of psychiatric disorders. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:2043–2053. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Chivers ML, Bailey JM. A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2002;13:89–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista KC, Muñoz RF, Gonzalez G. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in low-income and minority medical outpatients: description of a program and exploratory analyses. Cognitive Therapy Research. 1994;18:241–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: A meta-analysis. Aging and Mental Health. 2007;11:645–657. doi: 10.1080/13607860701529635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell DW, Campos PE, Perilla JL. Therapy with lesbians and gay men: A cognitive-behavioral perspective. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1996;2:391–415. [Google Scholar]

- Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto U.S. mental and addictive disorders service system. Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50:85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper WG. The etiology of male homosexuality. Medical Hypotheses. 1996;46:85–88. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. The relationship between life events and mental health in homosexual men. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;46:402–411. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199007)46:4<402::aid-jclp2270460405>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TGM, de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Schnabel P. Same-sex sexual behavior and psychiatric disorders: Findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence survey (NEMESIS) Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:85–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren S, Rogers T. Cognitive-behavioral therapy with gay, lesbian, and bisexual clients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57:629–643. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield JM. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for depressed, low-income minority clients: Retention and treatment enhancement. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1998;5:65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield JM. A cognitive behavioral approach to the beginning of the end of life: Minding the body. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield JM. Minding thebody: Workbook. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008b. [Google Scholar]

- Scogin F, Welsh D, Hanson A, Stump J, Coates A. Evidence-based psychotherapies for depression in older adults. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice. 2005;12:222–237. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, Hart AD, Tschanz JT, Plassman BL, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: The cache county study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:601–607. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Zane N, Nagayama-Hall GC, Berger LK. The case for cultural competency in psychotherapeutic interventions. Annual Review of Psychology. 60:10:1–10:24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163651. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist. 2007;62:271–286. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A supplement to mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. Mental health: Culture, race and ethnicity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Ettner S, Duan N, Miranda J, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:378–86. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahler J, Gabbay SG. Gay male aging: A review of the literature. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 1997;6:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Westin K. Families we choose. New York: Columbia University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Whitford GS. Realities and hopes for older gay males. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 1997;61:79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson KC, Mottram PG, Vassilas CA. Psychotherapeutic treatments for older depressed people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online) 2008;1:CD004853. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004853.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]