Abstract

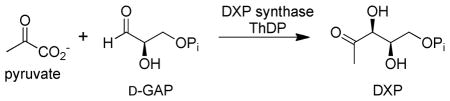

The thiamin diphosphate (ThDP)-dependent enzyme 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) synthase carries out the condensation of pyruvate as 2-hydroxyethyl donor with D-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (D-GAP) as acceptor forming DXP. Toward understanding catalysis of this potential anti-infective drug target, we examined the pathway of the enzyme using steady state and pre-steady state kinetic methods. It was found that DXP synthase stabilizes the ThDP-bound pre-decarboxylation intermediate formed between ThDP and pyruvate (C2α-lactylThDP or LThDP) in the absence of D-GAP, while addition of D-GAP enhanced the rate of decarboxylation by at least 600-fold. We postulate that decarboxylation requires formation of a ternary complex with both LThDP and D-GAP bound, and the central enzyme-bound enamine reacts with D-GAP to form DXP. This appears to be the first study of a ThDP enzyme where the individual rate constants could be evaluated by time-resolved CD spectroscopy, and the results could have relevance to other ThDP enzymes in which decarboxylation is coupled to a ligation reaction. The acceleration of the rate of decarboxylation of enzyme-bound LThDP in the presence of D-GAP suggests a new approach to inhibitor design.

INTRODUCTION

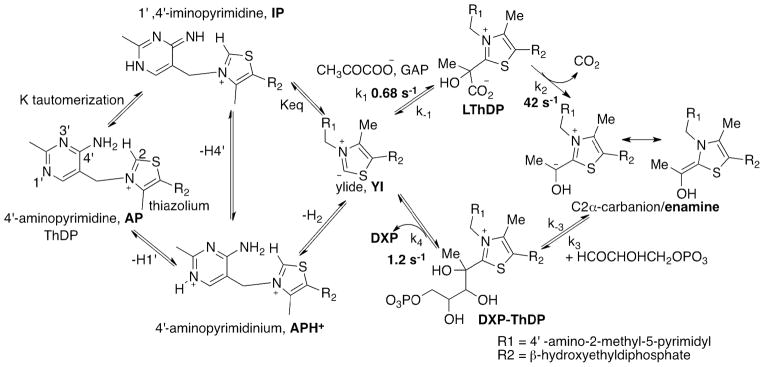

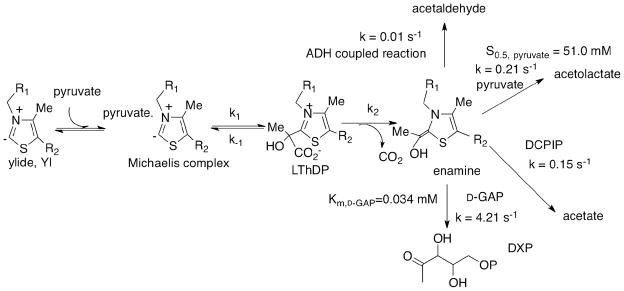

The enzyme 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) synthase generates the first crucial intermediate in the biosynthesis of both thiamin and pyridoxal, as well as in isoprenoid biosynthesis essential in human pathogens.1–3 DXP synthase uses ThDP as coenzyme and pyruvate and D-GAP as substrates. The reaction catalyzed by DXP synthase combines aspects of decarboxylase and carboligase enzymes. The chemical mechanism of the first step is likely to parallel typical ThDP-dependent pyruvate and other 2-oxoacid decarboxylase enzymes, the pyruvate forming a pre-decarboxylation covalent intermediate with ThDP (C2α-lactylThDP or LThDP) followed by decarboxylation to an enamine/C2α-carbanion/C2α-hydroxyethylidene-ThDP, which undergoes carboligation with the aldehyde functional group of D-GAP to form DXP (Scheme 1 right).

Scheme 1.

Pre-steady state detection of forward rate constant for individual steps in DXP synthase catalytic cycle at 6 °C with both pyruvate and GAP present in LThDP formation.

k1 formation of LThDP; k2 is decarboxylation to enamine; k3 is carboligation with D-GAP to provide DXP~ThDP; k4 is release of DXP product. CD studies assume that LThDP and DXP~ThDP when bound to DXP synthase are both in the IP tautomeric form while NMR can differentiate them by the method of Tittmann et al.14 The decarboxylation rate constant 4.2 × 101 s−1 pertains to k2.

Previous mechanistic studies of DXP synthase were performed under steady-state conditions.4–7 We report the first study of DXP synthase using tools capable of observing and determining the time-resolved behavior of ThDP-bound covalent intermediates (Scheme 1, right): stopped-flow circular dichroism (CD) and chemical quench followed by NMR detection. The CD method can monitor events on the enzyme itself, the NMR method monitors ThDP-bound intermediates after release from the enzyme (fortuitously, all the major ones are stable in acid), and is also useful to provide positive identification of the species seen in the CD spectrum. The CD studies take advantage of (a) identification of an electronic absorption for the 1′,4′-iminopyrimidine (IP form, Scheme 1 left) of ThDP at 300–310 nm8 and (b) demonstration on ten ThDP enzymes so far, that at pH values at or above the pKa of the 4′-aminopyrimidinium form (APH+) of ThDP, the IP tautomer predominates in ThDP-bound covalent intermediates where the C2α-carbon carries four substituents.9

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Thiamin diphosphate (ThDP), pyruvate, yeast alcohol dehydrogenase, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, 2,6-dichlorophenolindophenol (DCPIP), D,L-GAP, 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DXP) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). HEPES and dithiothreitol were from USB (Cleveland, OH).

Cloning, overexpression and purification of DXP synthase. DXP synthase was purified as reported previously.7

Activity measurement of DXP formation using coupled enzyme (IspC)

DXP synthase activity was measured spectrophotometrically using pyruvate and D,L-GAP, and IspC (DXP reductoisomerase) as a coupling enzyme as reported previously.7 Under these conditions D-GAP from a solution of D,L-GAP reacts exclusively to form DXP.10 Here we have used commercially available racemic D,L-GAP by knowing that L-GAP would not affect DXP synthase activity.1,5,6 The concentration of D-GAP was calculated as one half of the D,L-GAP concentration.

CD Spectroscopy

CD spectra were recorded on a Applied Photophysics Chirascan CD Spectrometer (Leatherhead, U.K.) in 2.4 mL volume with 1 cm path length cell.

Formation of LThDP from pyruvate by DXP synthase

DXP synthase (55.9 μM active centers) was titrated with pyruvate (0.05–1 mM) in 100 mM HEPES (pH 8.0) containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM ThDP and 1 mM MgCl2 at 4 °C. After apparent saturation with 1 mM pyruvate, 250 μM D-GAP was added. The Kd, app was calculated by fitting the data to a Hill function (equation S1, see SI).

Stopped-flow CD Spectroscopy

Kinetic traces were recorded on a Pi*-180 stopped-flow CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, U.K.) using 10 mm path length. ThDP-bound intermediates (LThDP specifically) were detected at 313 nm and DXP at 297 nm, as dictated by the high sensitivity of the lamp at those wavelengths. Data from ten repetitive shots were averaged and fit to the appropriate equation using Sigma Plot v.10.0.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where k1, k2 and k3 are the apparent rate constants, c is CDmaxλ in the exponential rise to maximum model or CDminλ in the exponential decay model.

Pre-steady state formation of 1′,4′-iminoLThDP

DXP synthase (68.1 μM active centers) in one syringe was mixed with equal volume of 2 mM pyruvate in the second syringe under pre-steady state conditions in buffer A (50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM ThDP, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1% glycerol) at 6 °C. The reaction was monitored at 313 nm for 7 s. Data were fit to a single-exponential model as in equation 1.

Single turnover experiments of DXP synthase with pyruvate in the absence of D-GAP

DXP synthase (81.4 μM active centers) in one syringe was mixed with equal volume of pyruvate (50 μM) in the second syringe, both in buffer A at 6 °C. The reaction was monitored at 313 nm for 50 s and data were fit to a triple exponential model as in Equation 2. The same experiment was carried out at 37 °C and data were fit to double exponential model as in equation 3.

Pre-steady state decarboxylation of 1′,4′-iminoLThDP in the presence of D-GAP

DXP synthase (68.1 μM active centers) was pre-mixed with 500 μM pyruvate at 6 °C to form LThDP in one syringe, then rapidly mixed with an equal volume of 100 μM D-GAP in the second syringe, both in buffer A at 6 °C. A similar experiment was performed using D-GAP (0.05–0.25 mM) and data were fit to equation 1.

Pre-steady state formation of DXP

DXP synthase (1.04 μM active centers) in buffer A placed in one syringe was mixed with an equal volume of 4 mM pyruvate and 2 mM D-GAP in the same buffer placed in the second syringe. Reaction was monitored by CD over a period of 100 s at 6 °C at 297 nm, and data were fitted to a double-exponential model as in equation 4.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR spectra were acquired on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz instrument. The water signal was suppressed by pre-saturation.

Detection of LThDP by 1H NMR spectroscopy

The reaction mixture containing DXP synthase (459.3 μM active centers) in 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ThDP and 0.5 mM MgCl2 was mixed with 1 mM pyruvate in the same buffer. The reaction mixture was incubated at 5 °C for 5 s (and an identical sample for 20 s) and quenched with 12.5% TCA in 1M DCl/D2O. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,700 g for 20 min, and the 1H NMR spectrum of the supernatant was recorded using 16384 scans with a recycle delay of 2.0 s.

Detection of DXP product by 1H NMR spectroscopy

A reaction mixture containing DXP synthase (22.22 μM active centers) in 20 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.5) containing 100 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM ThDP, 0.5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT was mixed with 15 mM D-GAP and 10 mM pyruvate in the same buffer. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, the 1H NMR spectrum of the supernatant was recorded.

RESULTS

The tautomeric and ionization states of ThDP on DXP synthase

The near-UV CD spectrum of DXP synthase displays a negative band at 320 nm (SI Figure S1A), suggesting the preponderance of the AP tautomer of ThDP bound to the enzyme.9 Next, the CD spectrum was recorded at different pH values to convert the AP form of ThDP to the APH+ form (Scheme 1 left). Reducing the pH from 7.98 to 7.07 gradually diminished the amplitude of the CD band at 320 nm (SI Figure S1A), indicating that the AP form of ThDP is dominant at pH 7.98, and the APH+ form is dominant at pH 7.07 [while the APH+ form has no CD signature identified so far, its existence on three ThDP enzymes was recently demonstrated by solid-state NMR].11 A plot of the CD320 against pH could be fitted to a single proton titrating with a pKa of 7.5 (SI Figure S1A, inset) for the protonic equilibrium ([AP] + [IP] )/[APH+]. This pKa elevation compared to the value of 4.85 in water 12 has been attributed to interaction via the short hydrogen bond between the N1′-atom of the 4′-aminopyrimidine and the highly conserved glutamate side chain.

Next, we determined the pH dependence of the rate of formation of DXP by DXP synthase to establish whether the pKa of the APH+ bears any relationship to the pH dependence of the activity. The rate of formation of DXP by DXP synthase determined at pH values of 6.65–8.08 (SI Figure S1B) revealed a pKapp of 7.6 (SI Figure S1B inset) which correlates well with the pKa of 7.5 for the protonic equilibrium ([AP]+[IP])/[APH+] (SI Figure S1A, inset). That is, the pKa of the enzyme-bound APH+ form is very near the pH of optimal activity of the enzyme7 signaling the need for all forms APH+, AP and IP in the mechanism, in accord with results on five other ThDP enzymes, thus creating a general trend.13

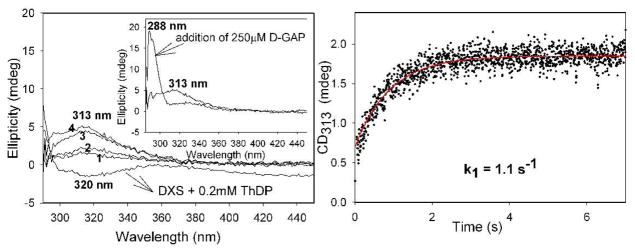

Direct observation of the pre-decarboxylation LThDP intermediate on DXP synthase

We next turned to CD studies of DXP synthase with the donor substrate pyruvate. On addition of saturating pyruvate at 4 °C, there developed a positive CD band at 313 nm (Figure 1, left), gradually replacing the negative CD band at 320 nm assigned to the AP form of ThDP (Scheme 1). The CD band at 313 nm revealed apparent saturation with pyruvate (apparent Kd, pyruvate ~ 90 μM, SI Figure S2), and was tentatively assigned to the 1′,4′-iminopyrimidinylLThDP. A stopped-flow CD experiment was designed to determine the rate of interconversion of the ThDP-bound covalent intermediates on DXP synthase. In the pre-steady state experiment, DXP synthase (68.1 μM active centers) in one syringe was rapidly mixed with saturating concentration of pyruvate (2 mM) in the second syringe, giving rise to an increase at 313 nm, and reaching a steady state in 2 s with rate constant of 1.1 ± 0.03 s−1 (Figure 1, right).

Figure 1.

Formation of 1′, 4′– iminoLThDP from pyruvate by DXP synthase. Left. CD titration of DXP synthase with pyruvate (1) 50 μM, (2) 100 μM, (3) 150 μM, (4) 1 mM. In- set: addition of 250 μM D-GAP generated DXP. Right. Rate of 1′, 4′–iminoLThDP formation at 6 °C.

The species represented by the positive CD band at 313 nm (signifying the presence of the IP tautomeric form of ThDP) could be assigned as either the pre-decarboxylation intermediate (LThDP) or the post-decarboxylation ThDP-bound DXP intermediate (Scheme 1, right), since both carry tetrahedral substitution at C2α. To resolve the ambiguity, an NMR method was used14, a method that recognized that the chemical shift of the C6′-H resonance is different for LThDP (7.26 ppm)14 and C2α-hydroxyethylThDP (HEThDP, 7.33 ppm)14, and indeed for carboligated product-ThDP adducts as well. Accordingly, an NMR spectrum of a mixture DXP synthase with pyruvate quenched in 5 s or 20 s revealed a chemical shift of 7.26 ppm, confirming that the CD at 313 nm corresponds to LThDP (SI Figure S3).14 Integration of the C2-H and C6′-H resonances showed that approximately the same % of ThDP was converted to LThDP in 5 s (~50%) and in 20 s (~55%), thus confirming the remarkable stability of LThDP on DXP synthase.

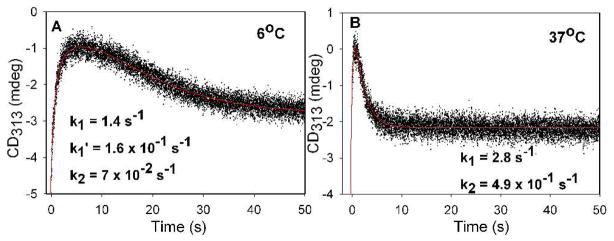

To interpret data once both pyruvate and D-GAP are present, we need to first establish rates of LThDP formation and decarboxylation in the absence of D-GAP. We accomplished this by a single turnover stopped-flow CD experiment with DXP synthase concentration in excess of pyruvate, carried out at 6 °C and 37 °C under the same conditions, the latter to enable comparison with alternative fates of the enamine intermediate. DXP synthase (81.4 μM active centers) in one syringe was mixed with an equal volume of pyruvate (50 μM) in the second syringe. The rates of LThDP formation and decarboxylation are k1 = 1.4 ± 0.05 s−1, k2 = (7 ± 0.01) × 10−2 s−1 at 6 °C (Figure 2A) and k1 = 2.8 ± 0.15 s−1, k2 = (4.9 ± 0.01) × 10−1 s−1 at 37 °C Figure 2B, Table 1).

Figure 2.

Formation and decarboxylation of LThDP on DXP synthase in the absence of D-GAP under single turn-over conditions A. at 6 °C and B. at 37 °C.

Table 1.

Rate constants for LThDP formation and decarboxylation on DXP synthase under pre-steady state conditionsa.

| Reaction with DXP synthase | k1 (s−1) | k2 (s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| pyruvate, 6 °C | 1.1 ± 0.03 | n.d |

| pyruvate (single turnover, 6 °C) | 1.4 ± 0.05 | (7±0.01) × 10−2 |

| pyruvate(single turnover, 37 °C) | 2.8 ± 0.15 | (4.9 ±0.01)×10−1 |

| pyruvate+D-GAP,6°C | (6.8±0.01)×10−1 | (4.2 ± 1.0) × 101 |

See detailed conditions in Experimental Section; n.d. not determined; see Scheme 1 right for assignment of rate constants to individual steps.

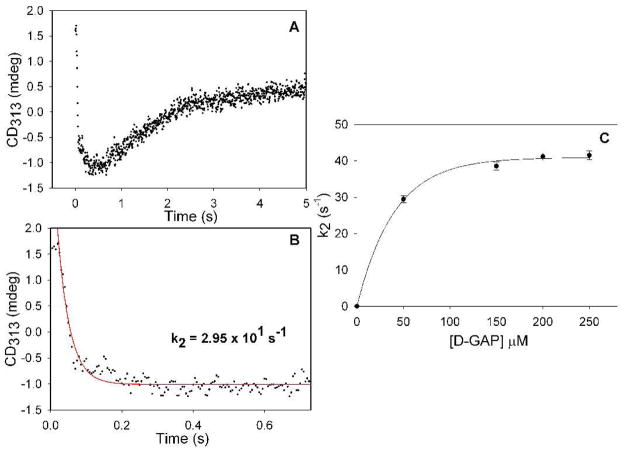

Direct observation of the rate of LThDP decarboxylation in the presence of D-GAP

Next, we wished to determine the effect of the acceptor substrate D-GAP on the rate of decarboxylation of LThDP. For these experiments, commercially available D,L-GAP was used as the source of D-GAP; L-GAP does not act as substrate for the enzyme (SI Figure S6).1,5,6,10 Addition of 250 μM D-GAP to DXP synthase with preformed LThDP (displayed a positive CD band at 313 nm in Figure 1, inset), resulted in formation of a new positive band at 288 nm, replacing the 313 nm band (Figure 1 left, inset). The CD spectrum of the supernatant after protein was removed indicated the persistence of the band at 288 nm, suggesting that it corresponds to the DXP product. Confirmation of the product was obtained with an NMR sample, prepared using DXP synthase (22.2 μM active centers) with pyruvate (10 mM) and D-GAP (15 mM), The 1H NMR spectrum identified the DXP in the supernatant by comparison with the spectrum of an ‘authentic’ commercially available DXP sample and that reported.1

Having observed accumulation of LThDP on the enzyme (Figure 1, left), we reasoned that direct monitoring of the CD at 313 nm (corresponding to LThDP) would enable us to directly measure the rate of decarboxylation upon the addition of D-GAP. As seen in Figure 1 left inset, the decarboxylation of LThDP is accelerated in the presence of the acceptor substrate D-GAP. To obtain quantitative support for this hypothesis, LThDP was preformed in one syringe by mixing DXP synthase (68.1 μM active centers) and pyruvate (500 μM) at 6 °C, then was rapidly mixed with D-GAP (100 μM) placed in the second syringe on the stopped-flow CD instrument. Time-dependent decarboxylation of LThDP (CD at 313 nm, Figure 3A) was observed with a rate constant of (3.0 ± 0.9) × 101 s−1 (Figure 3B), a rate constant that increases to (4.2 ± 1) × 101 s−1 for DXP synthase saturated with D-GAP (Figure 3C). An interpretation of the total behavior at 313 nm (Figure 3A) is that decarboxylation proceeds until all of the D-GAP is consumed (drop in the curve; the concentration of D-GAP reacting is 50 μM after mixing), after which time the remaining pyruvate forms more LThDP.

Figure 3.

A. Time course of LThDP decarboxylation and re-synthesis by DXP synthase in the presence of D-GAP at 6 °C. B. Expansion of early behavior in A fitting data to equation 1. C. Dependence of the rate of LThDP decarboxylation on final concentration of D-GAP.

To determine the rate of DXP release by CD, DXP synthase (1.04 μM active centers) in one syringe was mixed with pyruvate (4 mM) and D-GAP (2 mM) in the second syringe at 6 °C, providing a rate constant k4 = 1.2 ± 0.03 s−1 (SI Figure S4, bottom). The lower concentration of DXP synthase assured that the CD observations pertain to formation of free, rather than enzyme-bound DXP.

Putative acceptors for reactions of the enamine

As shown in Scheme 2, one could envision alternative competing trapping of the enamine resulting from LThDP decarboxylation, and the rates of these reactions needed to be established under the reaction conditions. A CD method was developed to measure the steady-state kinetic parameters for DXP synthase providing data consistent with the previous coupled assay.7 (1) With D-GAP as acceptor, the rate of DXP formation (4.21 s−1) at 37 °C was calculated from the slope of the progress curves recorded by CD with time at 290 nm. To calculate the rate constant, the molar ellipticity of DXP (13,200 deg cm2 dmol−1) was determined (SI Enzyme assays). (2) With a proton electrophile the enamine would be converted to HEThDP followed by release of acetaldehyde, whose rate of formation with the YADH/NADH coupled assay was 0.01 s−1. (3) With pyruvate as acceptor, carboligation of the enamine leads to (R)-acetolactate (negative CD band at 300 nm) in accord with the findings by the Johns Hopkins group.10 A CD titration of DXP synthase with pyruvate (1–90 mM) revealed a negative band centered at 300 nm, and the CD amplitude at 300 nm increased with increasing pyruvate concentration (SI Figure S5). Plotting the CD ellipticity at 300 nm against [pyruvate] gave S0.5, pyruvate of 51.0 ± 1.7 mM (SI Figure S5 inset) and a kcat = 0.21 s−1 was calculated. (4) Finally, the DCPIP reduction assay was carried out as evidence of decarboxylation, giving a rate constant of 0.15 s−1.

Scheme 2.

Putative acceptors for the enamine reactions under steady state conditions at 37 °C.

The rates of product formation from these putative acceptors at 37 °C (Scheme 2) indicate that formation of DXP is the preferred outcome by a significant factor, but that DXP synthase could indeed also produce significant (R)-acetolactate under some conditions.

DISCUSSION

Perhaps the most significant observation made from steady state CD was of a ‘stable’ ThDP-bound pre-decarboxylation intermediate with tetrahedral C2α substitution at 4 °C on DXP synthase in the absence of D-GAP; confirmed by NMR to be LThDP. Stopped-flow CD experiments enabled us to measure the rates of key steps on the putative reaction pathway of DXP synthase at 6 °C: the rate constant for formation of LThDP (1.1 s−1, k1 in Scheme 1), the rate constant of decarboxylation (4.2 × 101 s−1, k2 in Scheme 1 in the presence of D-GAP and 7 × 10−2 s−1 in its absence); the rate constant for carboligation k3 remains unknown but is almost certainly not rate limiting, and the rate constant for DXP release (1.2 s−1, k4 in Scheme 1). On the basis of this information, LThDP formation appears to be rate limiting. Most notable is the sizable rate acceleration on the decarboxylation step caused by the acceptor substrate D-GAP (Scheme 1). We note that in accord with our findings, Eubanks and Poulter4 first proposed a unique requirement for ternary complex formation in DXP synthase catalysis on the basis of CO2 trapping studies that showed significant reduction in rate of CO2 release in the absence of D-GAP. That study suggested that the presence of D-GAP is required for CO2 release; however, until now it was unknown whether binding of D-GAP facilitated formation of LThDP when both substrates are bound, or promoted decarboxylation of the LThDP intermediate. The CD approach used here permits the interrogation of these individual steps. Here, we show that the LThDP intermediate readily forms upon binding of pyruvate to DXP synthase in the absence of D-GAP, and persists at low temperature until addition of D-GAP.

The collective reports on DXP synthase mechanism are conflicting. Eubanks and Poulter4 provided the earliest compelling evidence for the requirement of a ternary complex, and proposed an ordered mechanism with pyruvate binding first. More recently, reports by Matsue et al.6 and Brammer, et al.7 have proposed ping-pong or random sequential mechanisms, respectively. On the basis of the evidence here that the LThDP intermediate persists at low temperature until addition of D-GAP, a classical ping-pong mechanism seems unlikely. The present results also exclude an ordered mechanism requiring GAP binding in the first step, since LThDP formation can clearly take place upon binding of pyruvate to free enzyme. The ordered and random sequential mechanisms previously proposed4,10 both support the idea that ternary complex formation is uniquely required in DXP synthase catalysis, in accordance with our findings here. A random substrate binding model cannot be directly tested here, as the presence of GAP facilitates rapid decarboxylation and precludes build-up of LThDP. While these results could support an ordered mechanism where pyruvate binds first, this CD analysis does not exclude the possibility that pyruvate can bind to an E-D-GAP complex and undergo conversion to LThDP in the presence of GAP, prior to GAP-promoted decarboxylation.

The 600-fold increase in rate of decarboxylation by DXP synthase as a result of D-GAP binding appears to be unique and supports the idea that ternary complex formation is required. The results should be evaluated in view of relevant studies on the decarboxylation of enzyme-bound LThDP. Tittmann and Wille summarized data on the ability to observe LThDP on a variety of ThDP enzymes15 and concluded the “LThDP to be extremely short lived and marginally accumulated at steady state, rendering a structural characterization of LThDP under steady state turnover or single turnover conditions almost impossible” although the NMR method did detect some LThDP in certain cases, such as in the F479W pyruvate oxidase variant.26 These observations were also summarized in a review by Kluger and Tittmann.16 In the experience of the Rutgers group, turnover numbers for ThDP-dependent pyruvate decarboxylating enzymes are in the range of (5–6) × 101 s−1, hence the rate constant for decarboxylation of enzyme-bound LThDP must be at least this large, more in the range of the rate constant here observed with D-GAP present.

Taking into consideration the long history of studies on rates of decarboxylation using non-enzymatic LThDP models, it could be inferred that the dielectric constant of the putative DXP synthase active site of the ternary complex may be low. Lienhard and coworkers showed that transferring the 2-(1-carboxy-1-hydroxyethyl)-3,4-dimethyl-thiazolium ion from water to ethanol led to a 104–105 fold increase in the decarboxylation rate.17 Kluger et al. reported a rate constant of 4 × 10−5 s−1 for decarboxylation of a C2α-lactylthiamin18 at pH 7.0 and 25 °C. More recently, a study by Zhang et al. demonstrated ‘spontaneous’ decarboxylation of C2α-lactylthiazolium salts with rate constants exceeding 50 s−1 in THF, simply by decreasing the dielectric constant of the solvent.19 Evidence supporting the idea of an apolar active site of yeast pyruvate decarboxylase (YPDC) was reported by Jordan et al.20 in a study utilizing thiochrome pyrophosphate, a fluorescent ThDP analog whose emission spectra correlates to solvent polarity. The effective active site dielectric constant for YPDC was interpolated to that between 1-hexanol and 1-pentnol (i.e., between 11–13), despite the existence of a Glu, an Asp and two His residues (in addition to the conserved glutamate) at the active center.

In view of these non-enzymatic models for LThDP decarboxylation rates reported in the previous paragraph, apparently, DXP synthase accelerates the rate of decarboxylation [k2 = (7 ± 0.01) × 10−2 s−1 at 6 °C] compared to the value reported in aqueous buffer (4 × 10−5 s−1). Yet, the lifetime of LThDP on DXP synthase in the absence of D-GAP is still surprisingly long in comparison with other enzymes carrying out the same function (see above). The 600-fold rate acceleration on addition of D-GAP on DXP synthase translates to an energy barrier lowering of 3.5 kcal/mol, achieving a rate constant very similar to that achieved in some non-enzymatic model systems.

The slow rate of decarboxylation of LThDP on the enzyme in the absence of D-GAP requires explanation.

A likely explanation to consider for the effect of D-GAP is that decarboxylation is reversible21–23 and CO2 release from the enzyme is potentiated by D-GAP binding. Several reports by Kluger et al. have focused on model studies of decarboxylation that have led to the proposal that decarboxylation is reversible on the ThDP enzyme benzoylformate decarboxylase.16,21 For benzoylformate decarboxylase and A28S benzaldehyde lyase, it was suggested that serine residue from the active site may act as nucleophile in CO2 trapping.24 The fact that we only observed LThDP both on the enzyme and once it is released from the enzyme suggests that if the LThDP is indeed at equilibrium with the enamine + CO2, acid quench should produce HEThDP. Given that HEThDP is not observed does not argue against this scenario, only suggests that the equilibrium lies far to the LThDP side.

A different explanation for the effect of D-GAP on the decarboxylation rate is based upon our understanding of the decarboxylation mechanism provided by Lienhard’s work25, and the need for a zwitterion charge distribution (positively charged thiazolium ring with carboxylate ionization state of the lactyl group) for optimal decarboxylation rate. Thus, it is possible that protonation of the carboxylate group by DXP synthase active site residues could reduce the rate of decarboxylation.

Understanding the origins of the slow decarboxylation rate in the absence of D-GAP and its acceleration in its presence could create a new opportunity for the design of selective inhibitors against this important enzyme.

CONCLUSION

In summary, a combination of steady state and time-resolved (pre-steady state) CD spectroscopy were used to study the individual rate constants in the DXP synthase reaction (Table 1 and Scheme 1). The results clearly demonstrate that formation of LThDP is the rate-limiting step. Apparently, the acceptor substrate D-GAP accelerates decarboxylation of LThDP significantly, while in the absence of D-GAP, decarboxylation is very slow. It is also clear that among the putative acceptors for the reaction with the enamine, D-GAP is the preferred acceptor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported at JHU by NIH-GM084998 and at Rutgers by NIH-GM-050380. We gratefully acknowledge Jessica Smith and Katie Heflin for assistance with the purification and activity determination of wild type DXP synthase used in this study.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Experimental conditions for DXP synthase enzyme assays and pH dependence of AP form of ThDP on DXP synthase and DXP formation. Figures representing pH dependence, Michaelis-Menten plot to determine the Km for D-GAP, HPLC analysis demonstrating utilization of D-GAP only from a racemic mixture, and NMR spectra of DXP product. “This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.”

References

- 1.Sprenger GA, Schörken U, Wiegert T, Grolle S, de Graaf AA, Taylor SV, Begley TP, Bringer-Meyer S, Sahm H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12857–12862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lois LM, Campos N, Putra SR, Danielsen K, Rohmer M, Boronat A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:2105–2110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill RE, Himmeldirk K, Kennedy IA, Pauloski RM, Sayer BG, Wolf E, Spenser ID. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30426–30435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.48.30426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eubanks LM, Poulter CD. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1140–1149. doi: 10.1021/bi0205303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sisquella X, de Pourcq K, Alguacil J, Robles J, Sanz F, Anselmetti D, Imperial S, Fernandez-Busquets X. FASEB J. 2010;24:4203–4217. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-155507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsue Y, Mizuno H, Tomita T, Asami T, Nishiyama M, Kuzuyama T. J Antibiot. 2010;63:583–588. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brammer LA, Smith JM, Wade H, Meyers CF. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36522–36531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.259747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nemeria N, Chakraborty S, Baykal A, Korotchkina LG, Patel MS, Jordan F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:78–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609973104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nemeria NS, Chakraborty S, Balakrishnan A, Jordan F. FEBS J. 2009;276:2432–2446. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brammer LA, Meyers CF. Org Lett. 2009;11:4748–4751. doi: 10.1021/ol901961q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balakrishnan A, Paramasivam S, Chakraborty S, Polenova T, Jordan FJ. Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:665–672. doi: 10.1021/ja209856x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cain AH, Sullivan GR, Roberts JD. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:6423–6425. doi: 10.1021/ja00461a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nemeria N, Korotchkina L, McLeish MJ, Kenyon GL, Patel MS, Jordan F. Biochemistry. 2007;46:10739–10744. doi: 10.1021/bi700838q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tittmann K, Golbik R, Uhlemann K, Khailova L, Schneider G, Patel M, Jordan F, Chipman DM, Dugglby RG, Hübner G. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7885–7891. doi: 10.1021/bi034465o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tittmann K, Wille G. J Mol Cat B: Enzymatic. 2009;61:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kluger R, Tittmann K. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1797–1833. doi: 10.1021/cr068444m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crosby J, Lienhard GE. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:5707–5716. doi: 10.1021/ja00722a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kluger R, Chin J, Smyth T. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:884–888. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Liu M, Yan Y, Zhang Z, Jordan F. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54312–54318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan F, Li H, Brown A. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6369–6373. doi: 10.1021/bi990373g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mundle SOC, Rathgeber S, Lacrampe-Couloume G, Sherwood Lollar B, Kluger R. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11638–11639. doi: 10.1021/ja902686h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Häussermann A, Rominger F, Straub BF. Chem Eur J. 2012 doi: 10.1002/chem..201202298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-James OM, Singleton DA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6896–6897. doi: 10.1021/ja101775s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brandt GS, Kneen MM, Petsko GA, Ringe D, McLeish MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:438–439. doi: 10.1021/ja907064w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crosby J, Stone R, Lienhard GE. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:2891–2900. doi: 10.1021/ja00712a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wille G, Meyer D, Steinmetz A, Hinze E, Golbik R, Tittmann K. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nchembio788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.