Abstract

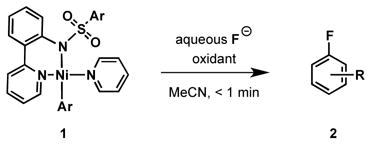

A one-step oxidative fluorination for carbon–fluorine bond formation from well-defined nickel complexes with oxidant and aqueous fluoride is presented, which enables a straightforward and practical 18F late-stage fluorination of complex small molecules with potential for PET imaging.

Positron emission tomography (PET) requires synthesis of molecules that contain positron-emitting isotopes, such as 11C, 13N, 15O, and 18F.1 The 18F isotope is typically the preferred radionuclide for clinically relevant PET applications due to its longer half-life of 110 minutes, which permits synthesis and distribution of radiotracer quantities appropriate for imaging.2 But C–F bond formation is challenging, especially with 18F.3 Here we report a practical late-stage fluorination reaction with high-specific activity 18F fluoride to make aryl and alkenyl fluorides from organometallic nickel complexes. A direct oxidative fluorination of organotransition metal complexes with oxidant and fluoride has never been reported, and enables practical one-step access to complex 18F-labeled small molecules from [18F]fluoride. When nickel complexes 1 are combined with oxidant and aqueous fluoride, the organic fluorides 2 are formed at room temperature in less than a minute (eq 1).

|

(1) |

Synthesis of simple 18F PET tracers is typically accomplished with conventional nucleophilic substitution reactions with [18F]fluoride.1,4 [18F]Fluoride is the only readily available source of F-18. But conventional nucleophilic substitution reactions commonly only give access to simple molecules, and have a small substrate scope. C–F bond formation is more difficult with 18F than with the naturally occurring 19F, and most modern, functional group-tolerant fluorination reactions are not currently useful for applications in PET.5 In addition to the challenges associated with 19F fluorination,3 chemistry with 18F needs to take into account the small concentration of 18F (roughly 10−4 M), the impracticality to work under rigorously anhydrous conditions, and the side product profile. We sought to develop a practical, one-step, functional group tolerant, electrophilic fluorination reaction that employs [18F]fluoride.

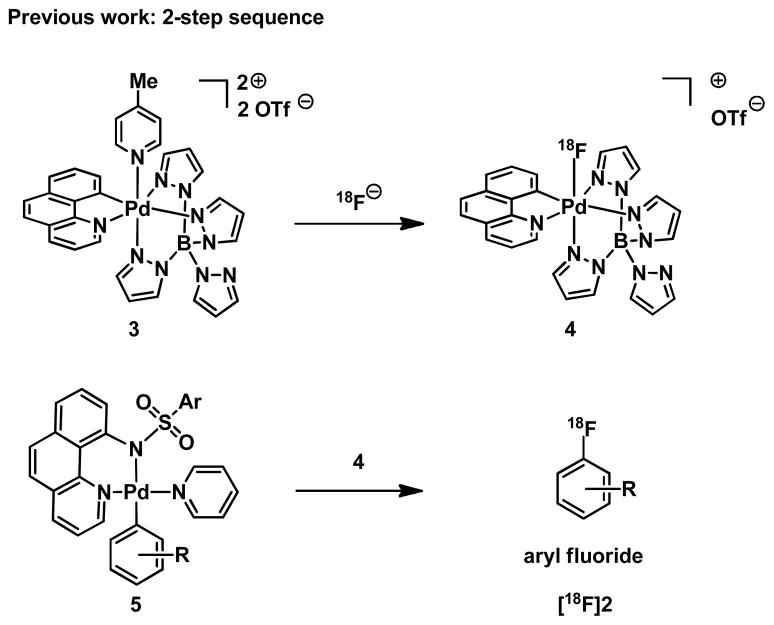

We had previously developed the electrophilic fluorination reagent 4 made from high-specific activity [18F]fluoride via reductive elimination from high-valent palladium fluoride complexes (Scheme 1).6 Palladium complex 4 can be used for late-stage 18F fluorination of complex arenes and was the first reagent to capture fluoride and subsequently function as electrophilic fluorination reagent. Yet, use of 4 requires a two-step sequence: fluoride capture (3 → 4), followed by fluoride transfer via electrophilic fluorination (5 → [18F]2). The 2-step sequence increases reaction time and possibility for error, and makes the method less suitable for adoption by non-chemists. Moreover, the fluoride must be dried azeotropically, as is common for most reactions that use [18F]fluoride.1

Scheme 1.

Two-Step Late-Stage Fluorination via Pd(IV) Fluoride Complex 4.

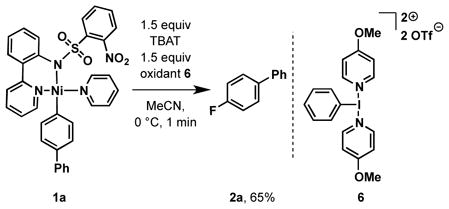

This manuscript reports on fluorination of arylnickel complexes that avoid some of the limitations inherent to the palladium chemistry shown in scheme 1, most notably the two-step procedure. We established the relevance of nickel aryl complexes 1 to the direct oxidative fluorination with fluoride through reaction of 1a with hypervalent iodine oxidant 6 and tetrabutylammonium difluorotriphenylsilicate (TBAT) as fluoride source, which afforded 65% isolated yield of aryl fluoride 2a after chromatographic purification on silica gel (eq 2).

|

(2) |

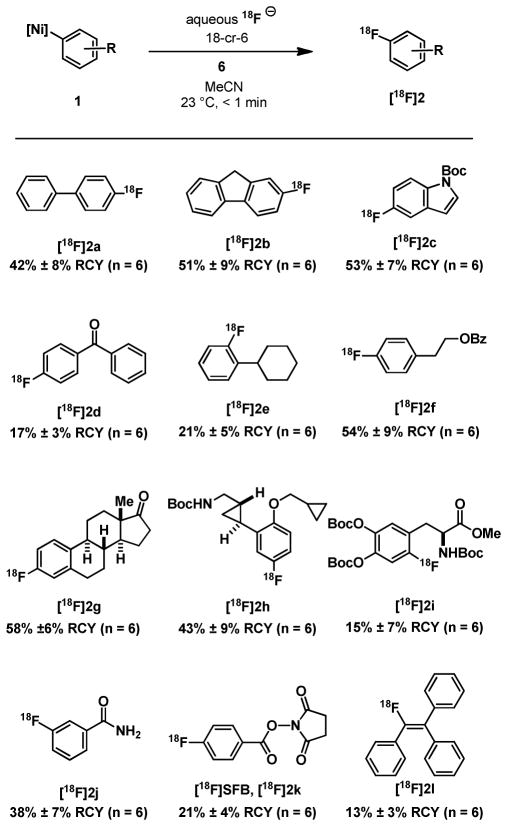

For radiofluorination, a solution of aqueous [18F]fluoride (2–5 μl, 100–500 μCi) containing 2 mg of 18-cr-6 in MeCN (200–500 μl) was added to a mixture of 1.0 mg of nickel complex 1 and 1.0 equivalents (relative to 1) of oxidant 6 at room temperature under ambient atmosphere in a vial. After less than one minute after addition, the fluorination reactions were analyzed by radioTLC and HPLC for radiochemical yield and product identity, respectively (Table 1). All reactions proceeded without deliberate addition of [19F]fluoride (no-carrier-added). No carrier-added 18F fluorination allows for the synthesis of 18F-labeled molecules of high specific activity.1 For example, compound 2g was prepared in 1.1 Ci·μmol−1. The transformation is successful for the synthesis of electron-rich, electron-poor, ortho-, meta-, and parasubstituted, and densely functionalized aryl fluorides, as well as for alkenyl fluorides. Tertiary amines are currently not tolerated, presumably due to unproductive reaction of oxidant 6 with nucleophiles such as amines.

Table 1.

Fluorination of Ni(II)-Aryl Complexes with [18F]Fluoride

|

Reaction conditions: 1.0 mg nickel complex 1, 1.0 equiv of 6 (with respect to 1), aqueous solution of [18F]fluoride (2–5 μl, 100–500 μCi; 500 μCi in 5 μl water corresponds to a concentration of 42 nM in [18F]), and 2.0 mg of 18-cr-6 in MeCN (200–500 μl) at 23 °C. Radiochemical yields (RCYs) were measured by radio-TLC, are based on original aqueous [18F] content and are averaged over n experiments. Boc, tert-butoxycarbonyl; Bz, benzoyl; SFB, N-succinimidyl 4-fluorobenzoate.

The ability to use aqueous fluoride solutions makes extensive drying procedures, that are typical for radiochemistry with [18F]fluoride,1 superfluous. Drying procedures increase the time from [18F] production to tracer purification; for example, drying fluoride for the reaction shown in scheme 1 takes longer than the 20-minute reaction time. The direct use of aqueous fluoride solution presented here avoids unproductive radioactive decay, and also increases the yield based on fluoride because drying commonly results in significant fluorine content absorbed onto walls of glass reaction vessels. The aqueous fluoride solution can be used without ion exchange that is normally required for radiochemistry with [18F]fluoride, which further increases practicality and reduces reaction time. To facilitate purification subsequent to fluorination, it is desirable to employ as little starting material (e.g. 1) as possible for radiofluorination, and 1 mg of nickel complex (ca. 1 μmol) is a low amount compared to other [18F] radiofluorination reactions. For example, the method presented here requires an order of magnitude less starting material than the palladium-mediated method described in Scheme 1, and still affords generally higher radiochemical yields.6

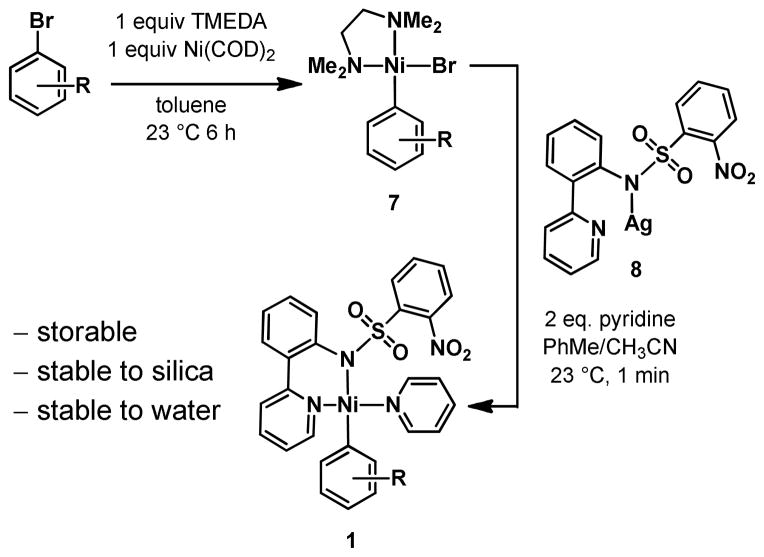

The synthesis of the nickel organometallics (1) is accomplished by oxidative addition of aryl or alkenyl bromides to commercially available Ni(COD)2 in the presence of tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA), followed by addition of silver salt 8 (Scheme 2). All reported nickel organometallics used for fluorination in this manuscript are moisture- and air-stable solids that can be purified by column chromatography on silica gel or recrystallization. The nickel complexes were prepared from the corresponding bromides in 30–92% yield and can be stored under ambient atmosphere.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Ni(II) Aryl Complexes

The one-step oxidative fluorination of well-defined nickel complexes with oxidant and aqueous fluoride enables a straightforward and practical 18F late-stage fluorination of complex small molecules.7 Operational simplicity of the fluorination, most notably the ability to use aqueous solutions of [18F]fluoride, will also empower non-experts to obtain previously unavailable 18F-labeled molecules, and showcases the potential of modern organometallic chemistry for applications in PET.7 The transformation represents the first example of fluorination with a first row transition metal organometallic, and the first example of a reaction that affords aryl fluoride by 18F–C bond formation at room temperature within seconds using an aqueous solution of 18F fluoride. Going forward, we will evaluate the possibility of translating the transformation to automated radiosyntheses as well as PET imaging applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIH-NIGMS (GM088237) and NIH-NIBIB (EB013042). We thank Dr. A. Kamlet for the synthesis of material used to prepare [18F]2h. We thank S.-L. Zheng (Harvard) for X-ray crystallographic analysis. We thank S. Carlin (Massachusetts General Hospital) for technical assistance with [18F]fluoride. TR is a Sloan fellow, a Lilly Grantee, an Amgen Young Investigator, a Camille Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar, and an AstraZeneca Awardee.

Footnotes

Notes

A patent application has been filed through Harvard on methods and reagents presented in this manuscript.

Detailed experimental procedures, spectroscopic data for all new compounds, crystallographic data for 1c (CIF). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8998–9033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Fowler JS, Wolf AP. Acc Chem Res. 1997;30:181. [Google Scholar]; (b) Phelps ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9226–9233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rohren EM, Turkington TG, Coleman RE. Radiology. 2004;231:305–332. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312021185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) O’Hagan D. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/b711844a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Furuya T, Kamlet AS, Ritter T. Nature. 2011;473:470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Pike VW, Aigbirhio FI. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1995:2215–2216. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chun JH, Lu SY, Lee YS, Pike VW. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3332–3338. doi: 10.1021/jo100361d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For the first transition metal-catalyzed C–18F bond formation, see Teare H, Robins EG, Kirjavainen A, Forsback S, Sandford G, Solin O, Luthra SK, Gouverneur V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:6821–6824. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002310.For other successful recent C–18F bond formation, see: Hollingworth C, Hazari A, Hopkinson MN, Tredwell M, Benedetto E, Huiban M, Gee AD, Brown JM, Gouverneur V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:2613–2617. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007307.Topczewski JJ, Tewson TJ, Nguyen HM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19318–19321. doi: 10.1021/ja2087213.Gao ZH, Lim YH, Tredwell M, Li L, Verhoog S, Hopkinson M, Kaluza W, Collier TL, Passchier J, Huiban M, Gouverneur V. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:6733–6737. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201502.

- 6.(a) Furuya T, Kaiser HM, Ritter T. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:5993–5996. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Furuya T, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10060–10061. doi: 10.1021/ja803187x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Furuya T, Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, Strom AE, Tang P, Goddard WA, III, Ritter T. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3793–3807. doi: 10.1021/ja909371t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee E, Kamlet AS, Powers DC, Neumann CN, Boursalian GB, Furuya T, Choi DC, Hooker JM, Ritter T. Science. 2011;334:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1212625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.For metal-catalyzed C–H to C–19F bond formation with fluoride and oxidant, see: McMurtrey KB, Racowski JM, Sanford MS. Org Lett. 2012;14:4094–4097. doi: 10.1021/ol301739f.Liu W, Huang X, Cheng MJ, Nielsen RJ, Goddard WA, III, Groves JT. Science. 2012;337:1322–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1222327.For other modern transition metal- catalyzed and -mediated C–F bond forming reactions with potential for applications in PET, see Watson DA, Su MJ, Teverovskiy G, Zhang Y, Garcia-Fortanet J, Kinzel T, Buchwald SL. Science. 2009;325:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.1178239.Katcher MH, Doyle AG. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:17402. doi: 10.1021/ja109120n.Noel T, Maimone TJ, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:8900–8903. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104652.Fier PS, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10795–10798. doi: 10.1021/ja304410x.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.