Abstract

Background

Nationwide surveys conducted in Japan over the past thirty years have revealed a four-fold increase in the estimated number of multiple sclerosis (MS) patients, a decrease in the age at onset, and successive increases in patients with conventional MS, which shows an involvement of multiple sites in the central nervous system, including the cerebrum and cerebellum. We aimed to clarify whether genetic and infectious backgrounds correlate to distinct disease phenotypes of MS in Japanese patients.

Methodology/Principal Findings

We analyzed HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 alleles, and IgG antibodies specific for Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumoniae, varicella zoster virus, and Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA) in 145 MS patients and 367 healthy controls (HCs). Frequencies of DRB1*0405 and DPB1*0301 were significantly higher, and DRB1*0901 and DPB1*0401 significantly lower, in MS patients as compared with HCs. MS patients with DRB1*0405 had a significantly earlier age of onset and lower Progression Index than patients without this allele. The proportion and absolute number of patients with DRB1*0405 successively increased with advancing year of birth. In MS patients without DRB1*0405, the frequency of the DRB1*1501 allele was significantly higher, while the DRB1*0901 allele was significantly lower, compared with HCs. Furthermore, DRB1*0405-negative MS patients were significantly more likely to be positive for EBNA antibodies compared with HCs.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that MS patients harboring DRB1*0405, a genetic risk factor for MS in the Japanese population, have a younger age at onset and a relatively benign disease course, while DRB1*0405-negative MS patients have features similar to Western-type MS in terms of association with Epstein-Barr virus infection and DRB1*1501. The recent increase of MS in young Japanese people may be caused, in part, by an increase in DRB1*0405-positive MS patients.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS). MS is rare in Asians, and is characterized by selective and severe involvement of the optic nerve and spinal cord: this form is termed opticospinal MS (OSMS) [1]. Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an inflammatory disease of the CNS selectively affecting the optic nerves and spinal cord. In NMO, longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions (LESCLs) extending over three or more vertebral segments are regarded as characteristic [2]. The nosological position of NMO has long been a matter of debate. However, the identification of immunoglobulins in NMO patients (NMO-IgG) that are specific for aquaporin-4 (AQP4) indicates that NMO is a distinct disease entity from MS [3], [4]. The classification of NMO has recently been expanded and the limited form of NMO is now named NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD) [5]. The NMO-IgG/AQP4 antibody is present in 30 to 60% of Japanese OSMS patients [6]–[8]; therefore, OSMS may be a similar entity to NMO. However, more than half of Asian OSMS patients do not have LESCLs, [9] and LESCLs are present in approximately one-fourth of patients with conventional MS (CMS), involving multiple sites of the CNS, including the cerebrum and cerebellum [10], [11]. Thus, in Asians, there is a considerable overlap between MS and NMO. Furthermore, the fourth nationwide survey of MS in Japanese people revealed that the most common type of MS was that with neither Barkhof brain lesions nor LESCLs [9].

MS risk and phenotype may be influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors [12]. Four nationwide surveys of MS conducted in Japan over thirty years revealed a four-fold increase in the estimated number of clinically definite MS patients in 2003 compared with 1972. In addition, a shift in the peak age at disease onset (from the early 30s in 1989 to the early 20s in 2003) and a successive increase in patients with CMS were observed [13]. This significant increase may be caused by ill-defined environmental changes such as “Westernization”, while reasons for the “earlier age at onset” are unknown.

Sanitary conditions have drastically improved because of the rapid lifestyle Westernization in Japan. Among many potential environmental risk factors, infection is likely to play a significant role in the acquisition of MS susceptibility or resistance. One candidate infectious agent is Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which is more prevalent in Caucasian MS patients than in healthy controls (HCs) and is, therefore, assumed to increase susceptibility to MS [14], [15]. However, epidemiological surveys suggest that frequent childhood infections may decrease susceptibility to MS [16], [17], as explained by the “hygiene hypothesis” [18]. In Japanese patients, an association of EBV with MS has not yet been demonstrated.

The largest genetic effect on MS susceptibility is caused by the major histocompatibility complex class II genes. In Caucasians, the HLA-DRB1*1501 allele is strongly associated with MS [19]. Recently, it was reported that the class I allele HLA-A*02 is also associated with MS, independently of DRB1*15, and has a protective effect [20]. In the Japanese population, several studies have reported that CMS is associated with HLA-DRB1*1501, while OSMS is associated with HLA-DPB1*0501 [21], [22]; no association was found with any HLA class I alleles [23]. However, most of these studies were performed before the identification of NMO-IgG, and, therefore, inevitably included NMO patients.

Thus, in the present study, we analyzed the genetic and infectious profiles of patients from the southern part of Japan with MS who did not fulfill the criteria for NMO or NMOSD. We sought to clarify: i) what the genetic and infectious risk factors for Japanese MS are; ii) whether genetically defined MS subtypes show distinct clinical and neuroimaging features; iii) whether a certain subtype of MS is more prevalent in younger Japanese patients; and iv) whether the profile of common infections are distinct or the same in genetically determined subtypes. In the present study, we focused on HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 loci that are associated with Japanese MS but not HLA class I, which have not shown any association with the disease.

Methods

Participants

One hundred and forty-five patients who were examined at the Neurology Departments of the University Hospitals of the South Japan MS Genetic Consortium (Co-investigator Appendix) between 1987 and 2010 were enrolled. MS was defined using the 2005 revised McDonald criteria for MS [24]. NMO was defined as cases fulfilling the 2006 revised criteria for NMO [25]. We regarded patients as having an NMOSD when the patients fulfilled either two absolute criteria plus at least one supportive criterion, or one absolute criterion plus more than one supportive criterion from the 2006 NMO criteria [25], primarily because there is considerable overlap between MS and NMO in Asians, as mentioned in the Introduction section. None of the MS patients met the above-mentioned NMO/NMOSD criteria. Patients with primary progressive MS were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from 145 patients and 367 unrelated HCs. We collected demographic data from the patients by retrospective review of their medical records. These data included gender, age of onset, disease duration, Kurtzke’s Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) scores [26], annualized relapse rate, Progression Index (PI) [27], cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) oligoclonal IgG bands (OB; as determined by isoelectric focusing [28]) and IgG index, brain MRI lesions that met the Barkhof criteria for MS [26], and the presence of LESCLs. The ethics committee of each institution approved this study.

MRI Analysis

All MRI studies were performed using 1.5 T units (Magnetom Vision and Symphony, Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) as previously described [6], [8]. Brain MRI lesions were evaluated according to the Barkhof criteria for MS [29]. Spinal cord lesions extending over three or more vertebral segments in length were considered to be LESCLs.

HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 Genotyping

The genotypes of the HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 alleles from the subjects were determined by hybridization between the products of polymerase chain reaction amplification of the HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 genes and sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes, as described previously [30].

AQP4 Antibody Assay

The presence of AQP4 antibodies was assayed as described previously [8], using green fluorescent protein (GFP)-AQP4 (M1 isoform) fusion protein-transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells. Serum samples diluted 1∶4 were assayed for the presence of AQP4 antibodies, and repeated at least twice using identical samples, with the examiners blinded to the origin of the specimens. Samples that gave a positive result twice were deemed positive.

Detection of Anti-Helicobacter pylori, Anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae, Anti-varicella Zoster Virus, and Anti-Epstein-Barr Virus Nuclear Antigen IgG Antibodies

Serum anti-Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), anti-Chlamydia pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae), anti-varicella zoster virus (VZV), and anti-Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen (EBNA) IgG antibodies were measured using commercial ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vircell, Granada, Spain), as described previously [31]. The antibody index was determined by dividing the optical density (O.D.) values for target samples by the O.D. values for cut-off control samples and then multiplying by 10. As recommended by the manufacturer, an ELISA test index value was considered positive if higher than 11, equivocal if between 9–11 and negative if less than 9. Samples with equivocal results were retested for confirmation. Samples that were equivocal twice were considered negative.

Statistical Analyses

The phenotype frequencies of the HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 alleles were compared using either the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test (when the criteria for the chi-square test were not fulfilled). We also conducted a dominant model of logistic regression analysis to identify HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 alleles associated with MS for alleles that have frequencies greater than 1% in subjects (cases and controls), and then conditioned on the top associated alleles to identify subsequently associated alleles. Estimation of HLA-DRB1-DPB1 haplotype frequencies and haplotype-based association analysis were performed using HaploView software. We checked the HLA-DRB1-DPB1 haplotypes that had frequencies greater than 1% in subjects. We used the Lewontin D’ measure to estimate the intermarker coefficient of linkage disequilibrium in both HCs and MS patients. Uncorrelated p-values (puncorr) were corrected by multiplying them by the number of comparisons, as indicated in the footnote of each table (Bonferroni–Dunn’s correction), to calculate the corrected p-values (pcorr). Fisher’s exact probability test was used to compare gender, CSF IgG abnormalities, brain MRI lesions that met the Barkhof criteria [29], frequencies of antibodies against common infectious agents among subgroups and the presence of LESCLs between subgroups. Other demographic features were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All analyses were performed using PLINK (version 1.07), Haploview (version 4.2), R (version 2.15) and JMP 8.0.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). We used PROC LOGISTIC (SAS Institute) to analyze the trends in the proportions of patients among subgroups with advancing year of birth using the Cochran-Armitage trend test. In all assays, p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Frequencies of HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 Alleles

Compared with HCs, the phenotype frequencies of the DRB1*0405 and DPB1*0301 alleles were significantly higher in MS patients (pcorr = 0.0013, OR = 2.230, 95% CI = 1.494–3.330, and pcorr = 0.0007, OR = 3.715, 95% CI = 1.879–7.347, respectively). By contrast, the frequencies of DRB1*0901 and DPB1*0401 were significantly lower (pcorr = 0.0002, OR = 0.281, 95% CI = 0.155–0.511, and pcorr = 0.0198, OR = 0.249, 95% CI = 0.097–0.641, respectively) (Tables 1 and 2). Even when a dominant model of logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify associations between HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 alleles and MS for alleles that had frequencies greater than 1% in subjects, we could not find any other associated alleles except for DRB1*0901, DRB1*0405, DPB1*0301, and DPB1*0401. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results (Tables S1 and S2); MS patients showed a higher frequency of DRB1*0405and DPB1*0301, and lower frequency of DRB1*0901 and DPB1*0401 compared with HCs.

Table 1. Frequencies of HLA-DRB1 alleles among MS patients and healthy controls.

| Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test | Logistic regression analysis | |||||||||||

| Phenotype frequency | Non adjusted | Adjusted with DRB1*0901 | Adjusted with DRB1*0901/DRB1*0405 | |||||||||

| MS (n = 145) | HCs (n = 367) | |||||||||||

| DRB1*X | n (%) | n (%) | pcorr | OR | 95%CI | pcorr | OR | 95%CI | pcorr | OR | 95%CI | pcorr |

| 0101 | 15 (10.3) | 51 (13.9) | 1 | 0.715 | 0.388–1.317 | 1 | 0.584 | 0.315–1.084 | 1 | 0.686 | 0.365–1.290 | 1 |

| 0403 | 9 (6.2) | 18 (4.9) | 1 | 1.283 | 0.563–2.926 | 1 | 1.239 | 0.535–2.869 | 1 | 1.385 | 0.591–3.244 | 1 |

| 0405 | 65 (44.8) | 98 (26.7) | 0.0013 | 2.230 | 1.494–3.330 | 0.0016 | 1.939 | 1.288–2.920 | 0.0273 | NA | NA | NA |

| 0406 | 17 (11.7) | 23 (6.3) | 0.6876 | 1.986 | 1.028–3.839 | 1 | 1.712 | 0.878–3.337 | 1 | 1.917 | 0.9715–3.783 | 1 |

| 0802 | 14 (9.7) | 26 (7.1) | 1 | 1.402 | 0.710–2.767 | 1 | 1.231 | 0.618–2.452 | 1 | 1.448 | 0.717–2.923 | 1 |

| 0803 | 19 (13.0) | 58 (15.8) | 1 | 0.803 | 0.460–1.404 | 1 | 0.678 | 0.385–1.195 | 1 | 0.745 | 0.420–1.323 | 1 |

| 0901 | 14 (9.7) | 101 (27.5) | 0.0002 | 0.282 | 0.155–0.511 | 0.0006 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 1101 | 5 (3.5) | 16 (4.4) | 1 | 0.784 | 0.282–2.180 | 1 | 0.749 | 0.265–2.114 | 1 | 0.822 | 0.288–2.343 | 1 |

| 1201 | 12 (8.3) | 33 (9.0) | 1 | 0.913 | 0.458–1.822 | 1 | 0.783 | 0.389–1.573 | 1 | 0.922 | 0.453–1.877 | 1 |

| 1202 | 2 (1.4) | 13 (3.5) | 1 | 0.381 | 0.085–1.709 | 1 | 0.340 | 0.075–1.539 | 1 | 0.349 | 0.076–1.597 | 1 |

| 1302 | 8 (5.5) | 49 (13.4) | 0.1998 | 0.379 | 0.175–0.822 | 0.2516 | 0.336 | 0.154–0.733 | 0.110 | 0.387 | 0.176–0.852 | 0.3300 |

| 1403 | 7 (4.8) | 8 (2.2) | 1 | 2.276 | 0.810–6.396 | 1 | 1.961 | 0.690–1.264 | 1 | 2.016 | 0.700–5.812 | 1 |

| 1405 | 4 (2.8) | 14 (3.8) | 1 | 0.715 | 0.232–2.210 | 1 | 0.666 | 0.213–2.085 | 1 | 0.713 | 0.225–2.257 | 1 |

| 1406 | 4 (2.8) | 8 (2.2) | 1 | 1.273 | 0.377–4.295 | 1 | 1.206 | 0.350–4.152 | 1 | 1.365 | 0.391–4.762 | 1 |

| 1454 | 5 (3.5) | 19 (5.2) | 1 | 0.654 | 0.240–1.786 | 1 | 0.607 | 0.220–1.677 | 1 | 0.679 | 0.244–1.894 | 1 |

| 1501 | 38 (26.2) | 60 (16.4) | 0.1908 | 1.817 | 1.145–2.885 | 0.2034 | 1.627 | 1.016–2.603 | 0.767 | 1.802 | 1.113–2.916 | 0.2992 |

| 1502 | 21 (14.5) | 80 (21.8) | 1 | 0.608 | 0.360–1.027 | 1 | 0.615 | 0.361–1.048 | 1 | 0.706 | 0.409–1.217 | 1 |

| Xa | 13 (9.0) | 22 (6.0) | ||||||||||

puncorr was corrected by multiplying the value by 18 to calculate pcorr.

Xa includes all observed alleles at the HLA-DRB1 locus with frequencies of less than 1% in subjects; DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0404, DRB1*0407, DRB1*0410, DRB1*0701, DRB1*1001, DRB1*1106, DRB1*1301, DRB1*1601 and DRB1*1602.

CI, confidence interval; HCs, healthy controls; MS, multiple sclerosis; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; pcorr, corrected p value.

Table 2. Frequencies of HLA-DPB1 alleles among MS patients and healthy controls.

| Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability test | Logistic regression analysis | |||||||||||

| Phenotype frequency | non adjusted | Adjusted with DPB1*0301 | Adjusted with DPB1*0301/DPB1*0401 | |||||||||

| MS (n = 145) | HCs (n = 367) | |||||||||||

| DPB1*X | n (%) | n (%) | pcorr | OR | 95%CI | pcorr | OR | 95%CI | pcorr | OR | 95%CI | pcorr |

| 0201 | 58 (40.0) | 117 (31.9) | 0.8094 | 1.425 | 0.957–2.121 | 0.8161 | 1.495 | 0.996–2.242 | 0.5217 | 1.385 | 0.919–2.086 | 1 |

| 0202 | 8 (5.5) | 19 (5.2) | 1 | 1.070 | 0.457–2.501 | 1 | 1.096 | 0.451–2.533 | 1 | 0.965 | 0.407–2.290 | 1 |

| 0301 | 21 (14.5) | 16 (4.4) | 0.0007 | 3.715 | 1.879–7.347 | 0.0016 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 0401 | 5 (3.5) | 46 (12.5) | 0.0198 | 0.249 | 0.097–0.641 | 0.0392 | 0.257 | 0.099–0.666 | 0.0512 | NA | NA | NA |

| 0402 | 27 (18.6) | 64 (17.4) | 1 | 1.083 | 0.659–1.782 | 1 | 1.195 | 0.7217–1.979 | 1 | 1.146 | 0.689–1.905 | 1 |

| 0501 | 102 (70.3) | 240 (65.4) | 1 | 1.255 | 0.830–1.903 | 1 | 1.526 | 0.981–2.374 | 0.610 | 1.351 | 0.861–2.119 | 1 |

| 0901 | 23 (15.9) | 80 (21.8) | 1 | 0.676 | 0.406–1.126 | 1 | 0.715 | 0.427–1.197 | 1 | 0.706 | 0.420–1.187 | 1 |

| 1301 | 4 (2.8) | 19 (5.2) | 1 | 0.520 | 0.174–1.554 | 1 | 0.583 | 0.194–1.747 | 1 | 0.594 | 0.196–1.795 | 1 |

| 1401 | 4 (2.8) | 10 (2.7) | 1 | 1.013 | 0.313–3.282 | 1 | 0.905 | 0.270–3.036 | 1 | 0.877 | 0.259 | 1 |

| Xb | 4 (2.8) | 5 (1.4) | ||||||||||

puncorr was corrected by multiplying the value by 10 to calculate pcorr.

Xb includes all observed alleles at the HLA-DPB1 locus with frequencies of less than 1% in subjects; DPB1*0601, DPB1*1601, DPB1*1701, DPB1*1901, DPB1*2201 and DPB1*4101.

CI, confidence interval; HCs, healthy controls; MS, multiple sclerosis; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; pcorr, corrected p value.

Frequency of HLA-DRB1 and -DPB1 Alleles in Subjects Lacking the HLA-DRB1*0405 Allele

Among individuals lacking the DRB1*0405 allele, the frequency of the DRB1*1501 allele was significantly higher (pcorr = 0.0030, OR = 2.831, 95% CI = 1.622–4.941) and that of the DRB1*0901 allele was significantly lower (pcorr = 0.0086, OR = 0.299, 95% CI = 0.147–0.608) in MS patients compared with HCs (Table 3). The frequency of DPB1 alleles were not significantly different between MS patients and HCs in subjects without the DRB1*0405 allele (data not shown).

Table 3. Comparison of phenotype frequencies of HLA-DRB1 alleles between MS patients and healthy controls in individuals without the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele.

| MS (n = 80) | HCs (n = 269) | ||||

| DRB1*X | n (%) | n (%) | OR | 95%CI | pcorr |

| 0101 | 11 (13.8) | 46 (17.1) | 0.773 | 0.380–1.574 | 1 |

| 0403 | 5 (6.3) | 17 (6.3) | 0.988 | 0.353–2.768 | 1 |

| 0406 | 11 (13.8) | 20 (7.4) | 1.985 | 0.908–4.341 | 1 |

| 0802 | 10 (12.5) | 24 (8.9) | 1.458 | 0.666–3.194 | 1 |

| 0803 | 15 (18.8) | 45 (16.7) | 1.149 | 0.602–2.192 | 1 |

| 0901 | 10 (12.5) | 87 (32.3) | 0.299 | 0.147–0.608 | 0.0086 |

| 1101 | 4 (5.0) | 13 (4.8) | 1.036 | 0.328–3.271 | 1 |

| 1201 | 7 (8.8) | 32 (11.9) | 0.710 | 0.301–1.676 | 1 |

| 1202 | 2 (2.5) | 9 (3.4) | 0.741 | 0.157–3.500 | 1 |

| 1302 | 6 (7.5) | 44 (16.4) | 0.415 | 0.170–1.012 | 0.8007 |

| 1403 | 3 (3.8) | 7 (2.6) | 1.458 | 0.368–5.774 | 1 |

| 1405 | 4 (5.0) | 10 (3.7) | 1.363 | 0.416–4.469 | 1 |

| 1406 | 3 (3.8) | 7 (2.6) | 1.458 | 0.368–5.774 | 1 |

| 1454 | 3 (3.8) | 17 (6.3) | 0.578 | 0.165–2.023 | 1 |

| 1501 | 29 (36.3) | 45 (16.7) | 2.831 | 1.622–4.941 | 0.0030 |

| 1502 | 17 (21.3) | 70 (26.0) | 0.767 | 0.421–1.399 | 1 |

| Xe | 12 (15.0) | 20 (7.4) |

puncorr was corrected by multiplying the value by 17 to calculate pcorr.

Xe includes all observed alleles at the HLA-DRB1 locus with frequencies of less than 1% in subjects; DRB1*0301, DRB1*0401, DRB1*0404, DRB1*0407, DRB1*0410, DRB1*0701, DRB1*1001, DRB1*1106, DRB1*1301, DRB1*1601 and DRB1*1602.

CI, confidence interval; HCs, healthy controls; MS, multiple sclerosis; OR, odds ratio; pcorr, corrected p value.

Frequency of DRB1-DPB1 Haplotypes

Compared with HCs, the haplotype frequencies in MS patients were significantly increased for the DRB1*0405-DPB1*0301 haplotype (puncorr = 0.0002, pcorr = 0.0042) (Table S3). However, the significance of this association was weaker than that of the DRB1*0405 allele (puncorr = 7.2×10−5, pcorr = 0.0013) or the DPB1*0301 allele (puncorr = 6.7×10−5, pcorr = 0.0007).

Comparison of Demographic Features between HLA-DRB1*0405-positive and -negative MS Patients

MS patients positive for DRB1*0405 showed an earlier age of onset, a lower EDSS score, a lower PI and a lower frequency of brain MRI lesions that met the Barkhof criteria [26] compared with patients without this allele (puncorr = 0.0014, puncorr = 0.0078, puncorr = 0.0017, and puncorr = 0.0272, respectively) (Table 4). The frequency of OB/increased IgG index was also lower in patients with DRB1*0405 than those without the allele, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (puncorr = 0.0859). Even after Bonferroni–Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons was made, MS patients positive for DRB1*0405 showed a significantly earlier age of onset and a significantly lower PI compared with those without this allele (pcorr = 0.0126 and pcorr = 0.0153, respectively). Furthermore, when eight MS patients with LESCLs were excluded, a similar difference in demographic features between MS patients with and without DRB1*0405 were observed (Table S4). Among patients without DRB1*0405, DRB1*1501-positive patients had a significantly higher frequency of CSF OB/increased IgG index than DRB1*1501-negative patients (17/19, 89.5% versus 20/33, 60.6%, p = 0.0312).

Table 4. Comparison of demographic features and clinical characteristic of MS patients according to the presence or absence of the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele.

| 0405 (+) (n = 65) | 0405 (−) (n = 80) | puncorr | pcorr | |

| Male: female | 22 : 43 | 29 : 51 | 0.8615 | 1 |

| Age at onset (years)a | 27.22±10.45 | 34.84±13.76 | 0.0014 | 0.0126 |

| Disease duration (years)a | 12.83±9.68 | 10.22±7.27 | 0.1211 | 1 |

| EDSS scorea | 2.48±2.05 | 3.49±2.37 | 0.0078 | 0.0702 |

| Annualized relapse ratea | 0.54±0.45 | 0.70±0.78 | 0.2290 | 1 |

| Progression Indexa | 0.33±0.42 | 0.66±1.38 | 0.0017 | 0.0153 |

| OB/increased IgG indexb | 22/42 (52.4%) | 37/52 (71.2%) | 0.0859 | 1 |

| Barkhof criteriac | 31/58 (53.5%) | 51/70 (72.9%) | 0.0272 | 0.2448 |

| LESCLs | 3/58 (5.2%) | 5/71 (7.0%) | 0.7295 | 1 |

Values represent the mean ± SD.

CSF oligoclonal IgG bands (OB) and/or increased IgG index (upper normal limit = 0.658, according to our previous study [21].

Brain MRI lesions that meet the Barkhof criteria [29].

EDSS, Kurtzke’s Expanded Disability Status Scale; LESCLs, longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions extending over three or more vertebral segments; MS, multiple sclerosis; OB, oligoclonal IgG bands.

puncorr was corrected by multiplying the value by nine to calculate pcorr.

Differences in the Distribution of HLA-DRB1*0405-positive and -negative MS Patients by Year of Birth

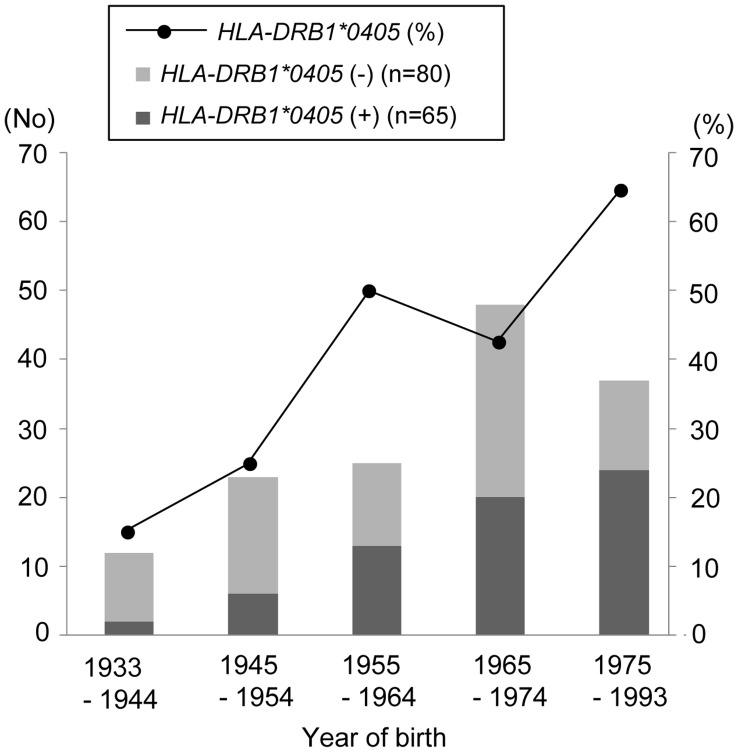

The proportion and absolute number of patients with DRB1*0405 successively increased with advancing year of birth (p = 0.0013, and p = 0.0005, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proportion of HLA-DRB1*0405-positive and -negative MS patients by year of birth.

Among MS patients, the proportion and absolute number of patients with DRB1*0405 successively increased with advancing year of birth. MS, multiple sclerosis.

Frequency of Anti-H. pylori, Anti-C. pneumoniae, Anti-VZV, and EBNA IgG Antibodies in MS and NMO

DRB1*0405-negative MS patients had a higher frequency of EBNA IgG antibodies compared with HCs, and DRB1*0405-positive MS patients (pcorr = 0.0324, and pcorr = 0.0033, respectively) (Table 5). Anti-H. pylori, anti-C. pneumoniae and anti-VZV antibody positivity rates did not differ significantly among the three subgroups.

Table 5. Frequencies of antibodies against common infectious agents among MS patients with and without the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele and healthy controls.

| Infections | HCs | HLA-DRB1*0405(−) MS | HLA-DRB1*0405(+) MS |

| EBV | 143/156 (91.67%) | 71/71 (100.0%)*a, *b | 48/56 (85.71%) |

| VZV | 153/156 (98.08%) | 70/71 (98.59%) | 56/56 (100.0%) |

| Helicobacter pylori | 74/177 (41.81%) | 23/71 (32.39%) | 21/56 (37.5%) |

| Chlamydia | 92/156 (58.97%) | 46/71 (64.79%) | 32/56 (57.14%) |

pcorr = 0.0324, as compared with HCs.

pcorr = 0.0033, as compared with HLA-DRB1*0405 (+) MS.

The age of patients during examination was not significantly different among HCs and MS patients, regardless of the presence or absence of the DRB1*0405 allele (mean ± SD in years; 35.22±12.18 in DRB1*0405-positive MS patients, 40.74±12.41 in DRB1*0405-negative MS patients, and 38.93±12.11 in HCs).

EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HCs, healthy controls; MS, multiple sclerosis; VZV, varicella zoster virus.

Discussion

The current study on Japanese MS patients, excluding patients with NMO, identified the following: (1) DRB1*0405 and DPB1*0301 are susceptibility alleles for MS. (2) DRB1*0405-positive MS patients showed an earlier age of disease onset and a relatively benign disease course. (3) The proportion and absolute numbers of DRB1*0405-positive patients among the total MS patients successively increased with advancing year of birth. (4) In DRB1*0405-negative MS patients, DRB1*1501 is a major susceptibility allele. (5) Susceptibility genes vary according to the disease phenotype, while DRB1*0901 is a common protective allele, irrespective of the phenotype. (6) Compared with healthy controls, DRB1*0405-negative MS patients had a significantly higher frequency of EBNA IgG antibodies. In the present study, the effect of the most strongly associated haplotype, the DRB1*0405-DPB1*0301 haplotype, on MS risk was lower than the effect of the DRB1*0405 allele or the DPB1*0301 allele alone. The linkage disequilibrium between the DRB1 and DPB1 loci is generally weak in the Japanese population [32]. Therefore, we focused on the association of a single marker, the DRB1 or DPB1 allele, which could be more meaningful than DRB1-DPB1 haplotypes in Japanese MS.

HLA-DRB1*0405-positive MS

The DRB1*0405 allele was found to be a significant risk determinant among Japanese patients with MS. A subgroup of DRB1*0405-positive MS patients showed distinct features: a younger age at disease onset, lower EDSS scores, a lower PI, and a lower frequency of MS-like brain lesions compared with DRB1*0405-negative patients. In addition, DRB1*0405-positive MS patients demonstrated a tendency for a lower frequency of CSF OB/increased IgG index compared with DRB1*0405-negative MS patients. This is in line with previous findings demonstrating that DRB1*04 is associated with OB-negative MS in Swedish [33] and Japanese populations [34]. A low prevalence of OB (54%) similar to that observed in the present study was also reported in Japanese MS patients as a unique feature compared with Western MS [1], [28]. The MS patients with DRB1*0405 may, in part, be responsible for this low prevalence of OB in Japanese MS patients. Even when Bonferroni–Dunn’s correction was performed, only MS patients positive for DRB1*0405 showed an earlier age of onset and a lower PI compared with patients without this allele. Therefore, DRB1*0405-positive MS could be a unique subgroup of MS that develops with a relatively benign disease course from an earlier age. According to the fourth nationwide survey of MS in Japanese people, the most common type of MS had neither Barkhof brain lesions nor LESCLs [9]. Hence, it is remarkable that such a subtype of MS with DRB1*0405 as a susceptibility risk is the most common in Japanese MS patients while it is present in a relatively minor population of Caucasian MS patients [33]. The proportion and absolute numbers of MS patients with DRB1*0405 have successively increased with advancing year of birth and this group of MS patients has a significantly younger age at disease onset. Therefore, the recently increased numbers of this subgroup of MS patients may explain the recently observed decrease in age at onset in Japanese MS patients, and could be partly responsible for the recent increase of MS prevalence in Japan [13]. However, it is still possible that MS patients with DRB1*0405 and a milder disease might have been previously overlooked and these patients might have been recently diagnosed as having MS owing to the increasingly widespread use of MRI. Thus, our findings should be confirmed by a large-scale study.

HLA-DRB1*0405-negative MS

DRB1*0405-negative MS patients had higher frequencies of DRB1*1501 and EBNA IgG antibodies compared with HCs. These two factors, which are also identified as risk factors for MS in Caucasians [35], are presumed to be risk factors for MS in DRB1*0405-negative Japanese subjects. DRB1*0405-negative MS patients had a significantly higher frequency of brain lesions fulfilling the Barkhof criteria. In these subjects, the presence of the DRB1*1501 allele was significantly associated with the CSF OB/increased IgG index. These features also resembled those of MS in Westerners [36], [37]. Therefore, this group of Japanese patients represents a “Western” type of MS in terms of clinical, neuroimaging, genetic, and infectious characteristics. The presence of the DRB1*1501 allele promotes the development of more T2 lesions [38] and positively interacts with EBV, a pathogen with a strong correlation to Caucasian MS [19], to increase MS susceptibility and disease burdens [39], [40]. Similar biological mechanisms may occur in Asian patients.

In the current study, DPB1*0301 was shown to be a significant risk allele in MS patients. An association of DPB1*0301 with MS has been reported in residents of Hokkaido in northern Japan [41] and in other ethnically diverse populations, such as Australians [42] and Sardinians [43]. However, the observed clinical features were not significantly different between the DPB1*0301-positive and -negative group in the MS patients from this study (data not shown).

A Common Genetic Background between HLA-DRB1*0405-positive and -negative MS Patients in Japanese Patients

The current study found that the DRB1*0901 allele had a strong protective effect against MS, regardless of the presence or absence of the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele. A recent meta-analysis in Chinese patients determined that the DRB1*0901 allele was protective for MS [44]. The DRB1*0901 allele is more frequently observed in Asians than in other ethnic groups (Japanese 30% vs. Caucasians 1%) [45]. Thus, one explanation for the lower MS prevalence in Japan and other Asian countries may be that the frequency of the DRB1*0901 allele is comparatively higher in those regions.

Limitations

The present study had some limitations; the numbers of enrolled MS patients were not large because the relative rarity of the disease in the Japanese population. However, this is the largest combined genetic and infection study undertaken in Asian countries, in which well-characterized cases were collected and were processed through the South Japan Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. In addition, after appropriate corrections for multiple comparisons were made, a number of findings were still statistically significant, which we hope will provide the basis for future studies and which should be confirmed by a large scale study.

Supporting Information

Frequency of HLA-DRB1 alleles among MS patients without LESCLs and healthy controls. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results; MS patients showed a significantly higher frequency of DRB1*0405, and lower frequency of DRB1*0901 compared with HCs.

(DOCX)

Frequency of HLA-DPB1 alleles among MS patients without LESCLs and healthy controls. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results; MS patients showed a significantly higher frequency of DPB1*0301, and lower frequency of DPB1*0401 compared with HCs.

(DOCX)

Frequency of DRB1-DPB1 haplotypes. Compared with HCs, the haplotype frequencies in MS patients were significantly increased for the DRB1*0405-DPB1*0301 haplotype.

(DOCX)

Demographic features of MS patients without LESCLs according to the presence or absence of the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results; MS patients positive for DRB1*0405 showed a significantly earlier age of onset and a significantly lower PI compared with those without this allele.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Junji Kishimoto (Center for Clinical and Translational Research, Kyushu University Hospital, Kyushu University) for his assistance with the statistical analyses. We thank all members of the South Japan Multiple Sclerosis Genetic Consortium for providing DNA samples and clinical information for this study.

The members of the South Japan Multiple Sclerosis Genetic Consortium are: Drs. Katsuichi Miyamoto (Kinki University, Site Investigator), Susumu Kusunoki (Kinki University, Chairman), Yuji Nakatsuji (Osaka University, Site Investigator), Hideki Mochizuki (Osaka University, Chairman), Kazuhide Ochi (Hiroshima University, Site Investigator), Masayasu Matsumoto (Hiroshima University, Chairman), Takeshi Kanda (Yamaguchi University, Chairman), Hirofumi Ochi (Ehime University, Site Investigator), Tetsuro Miki (Ehime University, Chairman), Kazumasa Okada (University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Site Investigator) and Sadatoshi Tsuji (University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Chairman).

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant on Intractable Diseases (H20-Nanchi-Ippan-016) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, and the grant-in-aid (B; no. 22390178) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kira J (2003) Multiple sclerosis in the Japanese population. Lancet Neurol 2: 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O'Brien PC, Weinshenker BG (1999) The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic's syndrome). Neurology 53: 1107–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, et al. (2004) A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet 364: 2106–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Verkman AS, Hinson SR (2005) IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J Exp Med 202: 473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG (2007) The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol 6: 805–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Matsuoka T, Matsushita T, Kawano Y, Osoegawa M, Ochi H, et al. (2007) Heterogeneity of aquaporin-4 autoimmunity and spinal cord lesions in multiple sclerosis in Japanese. Brain 130: 1206–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka K, Tani T, Tanaka M, Saida T, Idezuka J, et al. (2007) Anti-aquaporin 4 antibody in selected Japanese multiple sclerosis patients with long spinal cord lesions. Mult Scler 13: 850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsushita T, Isobe N, Matsuoka T, Shi N, Kawano Y, et al. (2009) Aquaporin-4 autoimmune syndrome and anti-aquaporin-4 antibody-negative opticospinal multiple sclerosis in Japanese. Mult Scler 15: 834–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishizu T, Kira J, Osoegawa M, Fukazawa T, Kikuchi S, et al. (2009) Heterogeneity and continuum of multiple sclerosis phenotypes in Japanese according to the results of the fourth nationwide survey. J Neurol Sci 280: 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Minohara M, Matsuoka T, Li W, Osoegawa M, Ishizu T, et al. (2006) Upregulation of myeloperoxidase in patients with opticospinal multiple sclerosis: positive correlation with disease severity. J Neuroimmunol 178: 156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsuoka T, Matsushita T, Osoegawa M, Ochi H, Kawano Y, et al. (2008) Heterogeneity and continuum of multiple sclerosis in Japanese according to magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Neurol Sci 266: 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ebers GC (2008) Environmental factors and multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 7: 268–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osoegawa M, Kira J, Fukazawa T, Fujihara K, Kikuchi S, et al.. (2009) Temporal changes and geographical differences in multiple sclerosis phenotypes in Japanese: nationwide survey results over 30 years. Mult Scler 15 159–173. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14. Levin LI, Munger KL, O'Reilly EJ, Falk KI, Ascherio A (2010) Primary infection with the Epstein-Barr virus and risk of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 67: 824–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Handel AE, Giovannoni G, Ebers GC, Ramagopalan SV (2010) Environmental factors and their timing in adult-onset multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 6: 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leibowitz U, Antonovsky A, Medalie JM, Smith HA, Halpern L, et al. (1966) Epidemiological study of multiple sclerosis in Israel. Part II. Multiple sclerosis and level of sanitation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 29: 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ponsonby AL, van der Mei I, Dwyer T, Blizzard L, Taylor B, et al. (2005) Exposure to infant siblings during early life and risk of multiple sclerosis. JAMA 293: 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yazdanbakhsh M, Kremsner PG, van Ree R (2002) Allergy, parasites, and the hygiene hypothesis. Science 296: 490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giovannoni G, Ebers G (2007) Multiple sclerosis: the environment and causation. Curr Opin Neurol 20: 261–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brynedal B, Duvefelt K, Jonasdottir G, Roos IM, Akesson E, et al. (2007) HLA-A confers an HLA-DRB1 independent influence on the risk of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2: e664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kira J, Kanai T, Nishimura Y, Yamasaki K, Matsushita S, et al. (1996) Western versus Asian types of multiple sclerosis: immunogenetically and clinically distinct disorders. Ann Neurol 40: 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamasaki K, Horiuchi I, Minohara M, Kawano Y, Ohyagi Y, et al. (1999) HLA-DPB1*0501-associated opticospinal multiple sclerosis: clinical, neuroimaging and immunogenetic studies. Brain 122: 1689–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ono T, Zambenedetti MR, Yamasaki K, Kawano Y, Kamikawaji N, et al. (1998) Molecular analysis of HLA class I (HLA-A and -B) and HLA class II (HLA-DRB1) genes in Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis (Western type and Asian type). Tissue Antigens 52: 539–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, Filippi M, Hartung HP, et al. (2005) Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald Criteria”. Ann Neurol 58: 840–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG (2006) Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 66: 1485–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kurtzke JF (1983) Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 33: 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poser S, Ritter G, Bauer HJ, Grosse-Wilde H, Kuwert EK, et al. (1981) HLA-antigens and the prognosis of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 225: 219–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakashima I, Fujihara K, Sato S, Itoyama Y (2005) Oligoclonal IgG bands in Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis. A comparative study between isoelectric focusing with IgG immunofixation and high-resolution agarose gel electrophoresis. J Neuroimmunol 159: 133–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barkhof F, Filippi M, Miller DH, Scheltens P, Campi A, et al. (1997) Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain 120: 2059–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsushita T, Matsuoka T, Isobe N, Kawano Y, Minohara M, et al. (2008) Association of the HLA-DPB1*0501 allele with anti-aquaporin-4 antibody positivity in Japanese patients with idiopathic central nervous system demyelinating disorders. Tissue Antigens 73: 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li W, Minohara M, Piao H, Matsushita T, Masaki K, et al. (2009) Association of anti-Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein antibody response with anti-aquaporin-4 autoimmunity in Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler 15: 1411–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mitsunaga S, Kuwata S, Tokunaga K, Uchikawa C, Takahashi K, et al. (1992) Family study on HLA-DPB1 polymorphism: linkage analysis with HLA-DR/DQ and two “new” alleles. Hum Immunol. 34: 203–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Imrell K, Landtblom AM, Hillert J, Masterman T (2006) Multiple sclerosis with and without CSF bands: clinically indistinguishable but immunogenetically distinct. Neurology 67: 1062–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kikuchi S, Fukazawa T, Niino M, Yabe I, Miyagishi R, et al. (2003) HLA-related subpopulations of MS in Japanese with and without oligoclonal IgG bands. Neurology 60: 647–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sundström P, Nyström L, Jidell E, Hallmans G (2008) EBNA-1 reactivity and HLA DRB1*1501 as statistically independent risk factors for multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Mult Scler 14: 1120–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wu JS, Qiu W, Castley A, James I, Joseph J, et al. (2010) Presence of CSF oligoclonal bands (OCB) is associated with the HLA-DRB1 genotype in a West Australian multiple sclerosis cohort. J Neurol Sci 288: 63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Romero-Pinel L, Martinez-Yélamos S, Bau L, Matas E, Gubieras L, et al. (2011) Association of HLA-DRB1*15 allele and CSF oligoclonal bands in a Spanish multiple sclerosis cohort. Eur J Neurol 18: 1258–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Okuda DT, Srinivasan R, Oksenberg JR, Goodin DS, Baranzini SE, et al. (2009) Genotype-phenotype correlations in multiple sclerosis: HLA genes influence disease severity inferred by 1HMR spectroscopy and MRI measures. Brain 132: 250–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buljevac D, van Doornum GJJ, Flach HZ, Groen J, Osterhaus ADME, et al. (2005) Epstein-Barr virus and disease activity in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76: 1377–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farrell RA, Antony D, Wall GR, Clark DA, Fisniku L, et al. (2009) Humoral immune response to EBV in multiple sclerosis is associated with disease activity on MRI. Neurology 73: 32–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fukazawa T, Yamasaki K, Ito H, Kikuchi S, Minohara M, et al. (2000) Both the HLA-DPB1 and -DRB1 alleles correlate with risk for multiple sclerosis in Japanese: clinical phenotypes and gender as important factors. Tissue Antigens 55: 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dekker JW, Easteal S, Jakobsen IB, Gao X, Stewart GJ, et al. (1993) HLA-DPB1 alleles correlate with risk for multiple sclerosis in Caucasoid and Cantonese patients lacking the high-risk DQB1*0602 allele. Tissue Antigens 41: 31–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marrosu MG, Murru R, Murru MR, Costa G, Zavattari P, et al. (2001) Dissection of the HLA association with multiple sclerosis in the founder isolated population of Sardinia. Hum Mol Genet 10: 2907–2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Qiu W, James I, Carroll WM, Mastaglia FL, Kermode AG (2010) HLA-DR allele polymorphism and multiple sclerosis in Chinese populations: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler 17: 382–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fujisao S, Matsushita S, Nishi T, Nishimura Y (1996) Identification of HLA-DR9 (DRB1*0901)-binding peptide motifs using a phage fUSE5 random peptide library. Human Immunol 45: 131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Frequency of HLA-DRB1 alleles among MS patients without LESCLs and healthy controls. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results; MS patients showed a significantly higher frequency of DRB1*0405, and lower frequency of DRB1*0901 compared with HCs.

(DOCX)

Frequency of HLA-DPB1 alleles among MS patients without LESCLs and healthy controls. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results; MS patients showed a significantly higher frequency of DPB1*0301, and lower frequency of DPB1*0401 compared with HCs.

(DOCX)

Frequency of DRB1-DPB1 haplotypes. Compared with HCs, the haplotype frequencies in MS patients were significantly increased for the DRB1*0405-DPB1*0301 haplotype.

(DOCX)

Demographic features of MS patients without LESCLs according to the presence or absence of the HLA-DRB1*0405 allele. Exclusion of eight MS patients with LESCLs gave essentially the same results; MS patients positive for DRB1*0405 showed a significantly earlier age of onset and a significantly lower PI compared with those without this allele.

(DOC)