Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium (NaV) and potassium (KV) channels are critical components of neuronal action potential generation and propagation. Here, we report that NaVβ1 encoded by SCN1b, an integral subunit of NaV channels, coassembles with and modulates the biophysical properties of KV1 and KV7 channels, but not KV3 channels, in an isoform-specific manner. Distinct domains of NaVβ1 are involved in modulation of the different KV channels. Studies with channel chimeras demonstrate that NaVβ1-mediated changes in activation kinetics and voltage dependence of activation require interaction of NaVβ1 with the channel’s voltage-sensing domain, whereas changes in inactivation and deactivation require interaction with the channel’s pore domain. A molecular model based on docking studies shows NaVβ1 lying in the crevice between the voltage-sensing and pore domains of KV channels, making significant contacts with the S1 and S5 segments. Cross-modulation of NaV and KV channels by NaVβ1 may promote diversity and flexibility in the overall control of cellular excitability and signaling.

Keywords: colocalization, gating, voltage-gated ion channels, patch-clamp, accessory subunit

Sequential opening and closing of central nervous system (CNS) voltage-gated sodium (NaV) and potassium (KV) channels mediate the depolarization phase (1) and repolarization phase (2, 3), respectively, of neuronal action potentials. Although intrinsic domains within the NaV α subunits underlie voltage-dependent gating properties and sodium-specific permeation, five NaVβ subunits (β1, β1B, β2, β3, β4) assemble with and modulate inactivation kinetics and the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation of NaV α subunits (1, 4). In addition, these NaV β subunits function in cell adhesion and contribute to neuronal migration, pathfinding, and fasciculation (4–8). Given their ubiquitous roles and distribution in the CNS, NaV β subunits play a major role in fine-tuning of action potential generation, propagation, and frequency. Subtle changes to their function have resulted in a range of detrimental neurological diseases in humans such as genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), Dravet syndrome (severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy), temporal lobe epilepsy, febrile seizures, and decreased responsiveness to the anticonvulsant drugs carbamazepine and phenytoin (7–12).

KV channels are important contributors to action potential repolarization. KV channels in mammals are encoded by 40 genes grouped into 12 subfamilies (KV1–KV12). NaVβ1, which was previously thought to be specific for NaV channels, was recently shown to coassemble with and modulate the properties of the KV4.x subfamily of channels (13–15). In the rodent heart, NaVβ1 coprecipitates with KV4.3, and in heterologous expression systems it increases the amplitude of the KV4.3 current and speeds up activation (14, 15). In the rodent brain, NaVβ1 coprecipitates with KV4.2, and in heterologous expression systems it enhances surface expression of the channel and increases current amplitude (13). Genetic knockout of NaVβ1 in mice prolongs action potential firing in pyramidal neurons through its action on KV4.2 (13).

Here, we examined whether the NaVβ1–KV4.x interaction was specific for this family of KV channels, or whether NaVβ1 could interact and modulate the functions of other families of KV channels in mammals. We selected three families of KV channels (KV1, KV3, and KV7) for these studies. We report that NaVβ1 modulates the function of KV1.1, KV1.2, KV1.3, KV1.6, and KV7.2 channels, but not KV3.1 channels, in an isoform-specific manner. Through the use of chimeric and mutational strategies we identified regions in NaVβ1 and KV channels required for channel modulation, and docking simulations suggest a molecular model of the interaction of the two proteins.

Results

NaVβ1 Interacts with and Modulates KV1.x Channels.

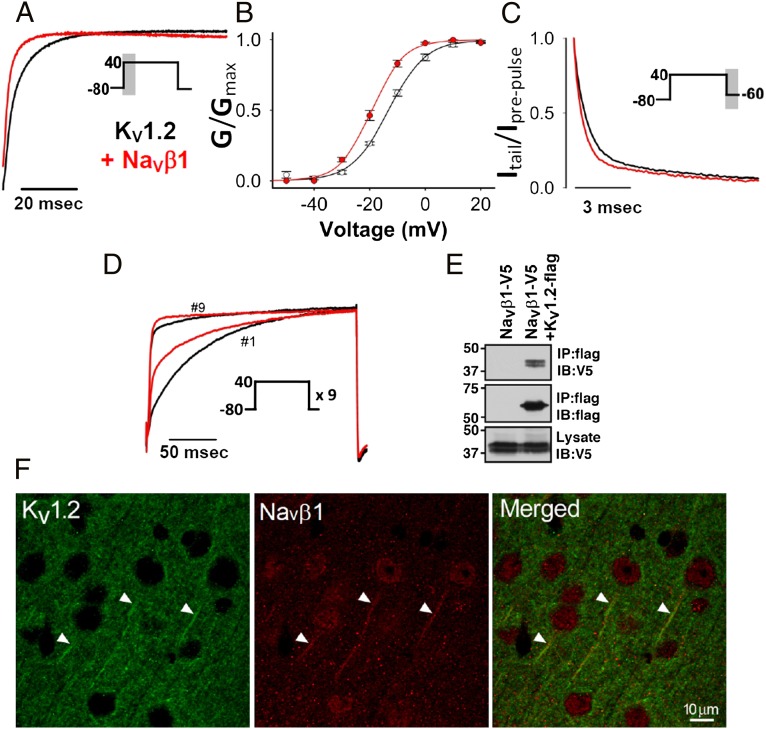

We examined the ability of NaVβ1 to modulate activation kinetics, voltage dependence of activation and deactivation of KV1.x channels expressed in mammalian cells or in Xenopus oocytes. In Xenopus oocytes, NaVβ1 accelerated KV1.2 activation, shifted the voltage dependence of activation in the hyperpolarized direction and sped up the fast component of deactivation (τfast at −60 mV) (Fig. 1 A–C). In mammalian cells, KV1.2 exhibited use-dependent activation (i.e., successive depolarizing pulses progressively increase the amplitude of the KV1.2 current and speed up activation), a unique property of this channel (16). NaVβ1 significantly accelerated KV1.2 activation (τfast at +40 mV) at the first pulse and to a lesser extent at the ninth pulse (Fig. 1D). Coprecipitation experiments demonstrated that NaVβ1 (dual-tagged at the C terminus with V5 and His6×) and mouse KV1.2 (FLAG-tagged at the C terminus) coassembled when heterologously expressed in mammalian cells (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, immunostaining experiments on normal mouse brain showed KV1.2 colocalization with NaVβ1 in the axon initial segment of neurons in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 1F) but not in nodes of Ranvier (Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1.

Activation kinetics at +40 mV (A, gray hatched area in pulse protocol represents first 30 ms analyzed), voltage dependence of activation (B) (mean ± SEM), and deactivation (C, gray hatched area in pulse protocol represents last 10 ms analyzed) of KV1.2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes in the presence or absence of NaVβ1 (n ≥ 7). Only currents of comparable amplitude between channel-alone, channel plus NaVβ1, were selected for analysis. (D) KV1.2 stably expressed in L929 fibroblasts exhibits use-dependent activation when repetitive depolarizing pulses at +40mV are administered at 1-s intervals. Average normalized current traces show NaVβ1 speeds up activation of KV1.2 at the first pulse and to a lesser extent at the ninth pulse (KV1.2, n = 6; KV1.2 + NaVβ1, n = 9 cells). (E) Western blot of coprecipitation experiment in transfected HEK cells showing that KV1.2 and NaVβ1 coassemble. (F) Mouse cerebral cortex immunostained for KV1.2 (green; Left) and NaVβ1 (red; Center), showing colocalization in the axon initial segment in the merged image (Right).

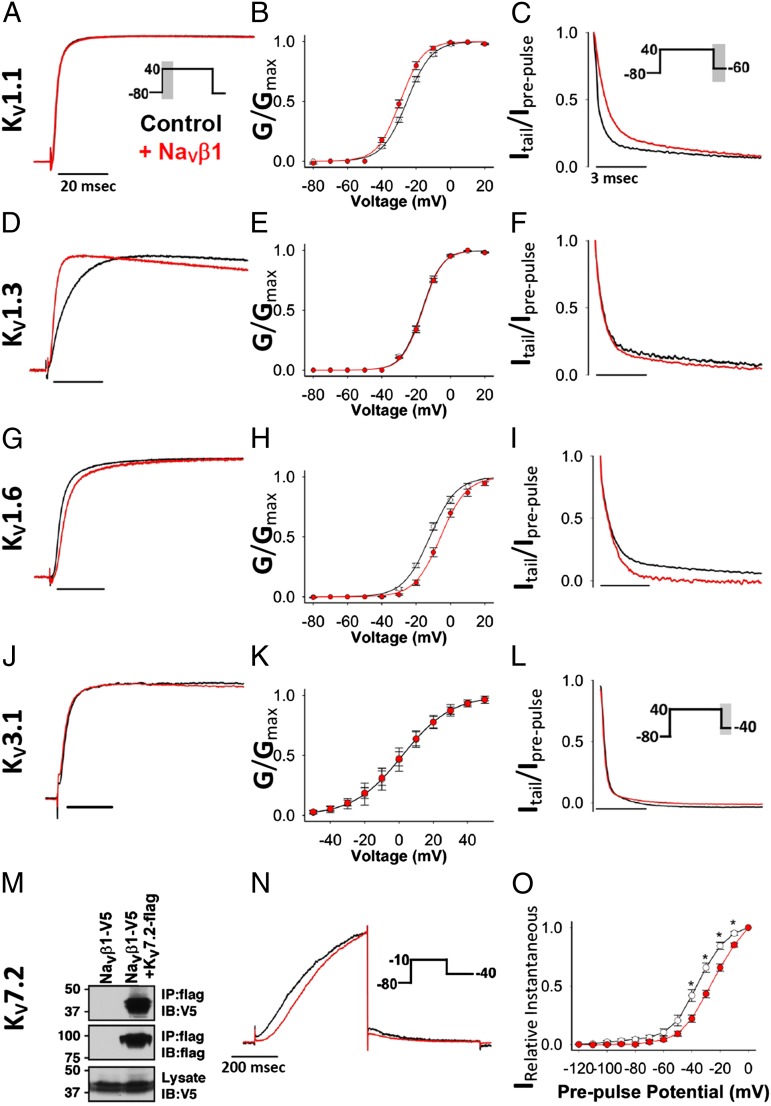

KV1.1 and KV1.3 had a different staining pattern and did not colocalize with NaVβ1 in normal mouse brain (Fig. S1 B and C). However, these channels may colocalize with NaVβ1 in demyelinating diseases where their distribution is altered (17–19). We therefore tested the effect of NaVβ1 on KV1.1, KV1.3, and KV1.6 channels (Table S1). NaVβ1 shifted the voltage dependence of activation of KV1.1 by ∼4 mV in the hyperpolarized direction and it slowed deactivation (τfast) of the channel without affecting its activation kinetics (Fig. 2 A–C). NaVβ1 significantly accelerated activation of KV1.3 in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 2D) and in mammalian cells (Fig. S2F) but had no effect on KV1.3’s voltage dependence of activation or deactivation kinetics (Fig. 2 E and F). NaVβ1 significantly reduced cumulative inactivation of KV1.3 (Fig. S2 A–C), a unique property of KV1.3 where successive depolarizing pulses cause a progressive diminution in the amplitude of the KV1.3 current as channels accumulate in the C-type inactivated state (18). His-tagged NaVβ1 complexes with and accelerates activation of KV1.3 in mammalian cells and Xenopus oocytes (Fig. S2 D–F). NaVβ1 slowed KV1.6’s activation, shifted its voltage dependence of activation in the depolarized direction, and significantly increased the amplitude of the KV1.6 tail current, but had no effect on the channel’s deactivation kinetics (Fig. 2 G–I). Endogenous KV channels in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells, which include KV1.x channels (20, 21), were also modulated by NaVβ1 (Fig. S3). Thus, NaVβ1’s modulatory effects on KV1 channels vary in an isoform-specific manner.

Fig. 2.

Activation kinetics (A, D, G, and J), voltage dependence of activation (B, E, H, and K) (mean ± SEM), and deactivation kinetics (C, F, I, and L) of KV1.1, KV1.3, KV1.6, and KV3.1 expressed alone (black) or with NaVβ1 (red) in Xenopus oocytes (KV1.1, KV1.3, and KV1.6) or mammalian cells (KV3.1) (n ≥ 5). (M) Western blot of coimmunoprecipitation experiment in transfected HEK cells showing that KV7.2 and NaVβ1 coprecipitate. (N) NaVβ1 slows activation of the KV7.2 current in CHO cells at moderate depolarizing potentials (n = 5). (O) Relative instantaneous current of KV7.2 shows a significant difference in the 1-s prepulse potential in the presence of NaVβ1 (n = 9).

NaVβ1 Modulates KV7 Channels but Not KV3 Channels.

The KV3 family contains four members, KV3.1–KV3.4. KV3.1 is a fast-activating/fast-deactivating channel that regulates spike frequency in several brain regions (22–24). When expressed heterologously in mammalian cells, NaVβ1 had no effect on activation kinetics, voltage dependence of activation or deactivation of KV3.1 (Fig. 2 J–L).

The KV7 family contains five members, KV7.1–KV7.5. KV7.2 and KV7.3 are the main molecular components of the neuronal M-current, a noninactivating, slowly deactivating, subthreshold current that regulates neuronal excitability (25). We examined whether NaVβ1 modulated KV7.2 channels, which are found in the axon initial segment and at nodes of Ranvier (25). In mammalian cells, NaVβ1 coassembled with FLAG-tagged KV7.2 (Fig. 2M), and it slowed the channel’s activation at moderate depolarization voltages (Fig. 2N, Fig. S4) and altered current measured at different 1-s prepulse potentials (Fig. 2O). These data together with those presented in Fig. 1 and in the literature (13–15) demonstrate that NaVβ1 modulates KV1.1, KV1.2, KV1.3, KV1.6, KV4.2, KV4.3, and KV7.2, but not KV3.1, each in a unique fashion.

Distinct Domains of NaVβ1 Are Involved in KV Channel Modulation.

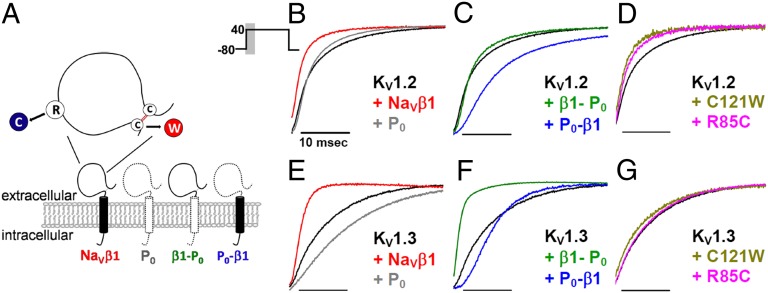

NaVβ1 and myelin zero (P0), the major protein in peripheral nerve myelin (26), are both type-1 membrane proteins that contain an extracellular Ig fold, a single transmembrane segment, and an intracellular C-terminal region (27) (Fig. 3A). NaVβ1 sped up acceleration of KV1.2 and KV1.3, whereas P0 slowed down KV1.3 activation and had no effect on KV1.2 activation (Fig. 3 B and E). Because NaVβ1 and P0 have different effects on KV1.2 and KV1.3, we used two chimeras of NaVβ1 and P0 to define the regions required for modulation of these channels (Fig. 3A). These chimeras were previously used to identify NaVβ1 domains required for NaV channel modulation (28). The NaVβ1-P0 chimera contains the extracellular Ig domain of NaVβ1 and the transmembrane and intracellular segments of P0, whereas the P0-NaVβ1 chimera contains the extracellular domain of P0 and the transmembrane and intracellular segments of NaVβ1 (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of NaVβ1 (red), myelin P0 protein (blue), and their chimeras (A). Inset, Extracellular domain of NaVβ1 showing the R85C and C121W epilepsy-causing mutations. (B and E) Effect on KV1.2 and KV1.3 activation kinetics by NaVβ1 versus P0 (B and E), chimeras (C and F), and NaVβ1 mutants (D and G) studied in Xenopus oocytes. Current traces are averages of normalized, representative currents of comparable amplitudes and shown are the first 30-ms activating phase of the 200-ms traces.

The external Ig domain of NaVβ1 is solely responsible for acceleration of KV1.3 activation because the NaVβ1-P0 chimera (containing NaVβ1’s external domain) sped up KV1.3 activation like NaVβ1, but the P0-NaVβ1 chimera (containing NaVβ1’s transmembrane/intracellular domain) had no effect (Fig. 3B). In support, two GEFS+ mutations (C121W and R85C) that disrupt the external Ig domain abolished NaVβ1-mediated acceleration of KV1.3 activation (Fig. 3C). The external domain of NaVβ1 was also responsible for reducing cumulative inactivation of KV1.3 because the NaVβ1-P0 but not the P0-NaVβ1 chimera significantly reduced cumulative inactivation, and the two GEFS+ mutations abolished this modulation (Fig. S5 A and B).

Full-length NaVβ1 accelerated KV1.2 activation but neither chimera recapitulated this modulation, indicating that the entire protein is required (Fig. 3 E–G). Two NaVβ1 GEFS+ mutants with a disrupted external Ig domain accelerated KV1.2 activation like NaVβ1 (Fig. 3E), indicating that an intact external Ig domain is also not sufficient for this modulation.

Full-length NaVβ1 slowed KV1.1 deactivation (Fig. 2C). This modulation requires the transmembrane and/or cytoplasmic region of NaVβ1 because the C121W NaVβ1 mutant was as effective as full-length NaVβ1 in slowing KV1 deactivation (Fig. S5C). Collectively, our results demonstrate that distinct NaVβ1 domains are required for modulating different KV channels, each in a channel isoform-specific manner.

NaVβ1 Interacts with the Voltage-Sensing and Pore Domains of KV1 Channels.

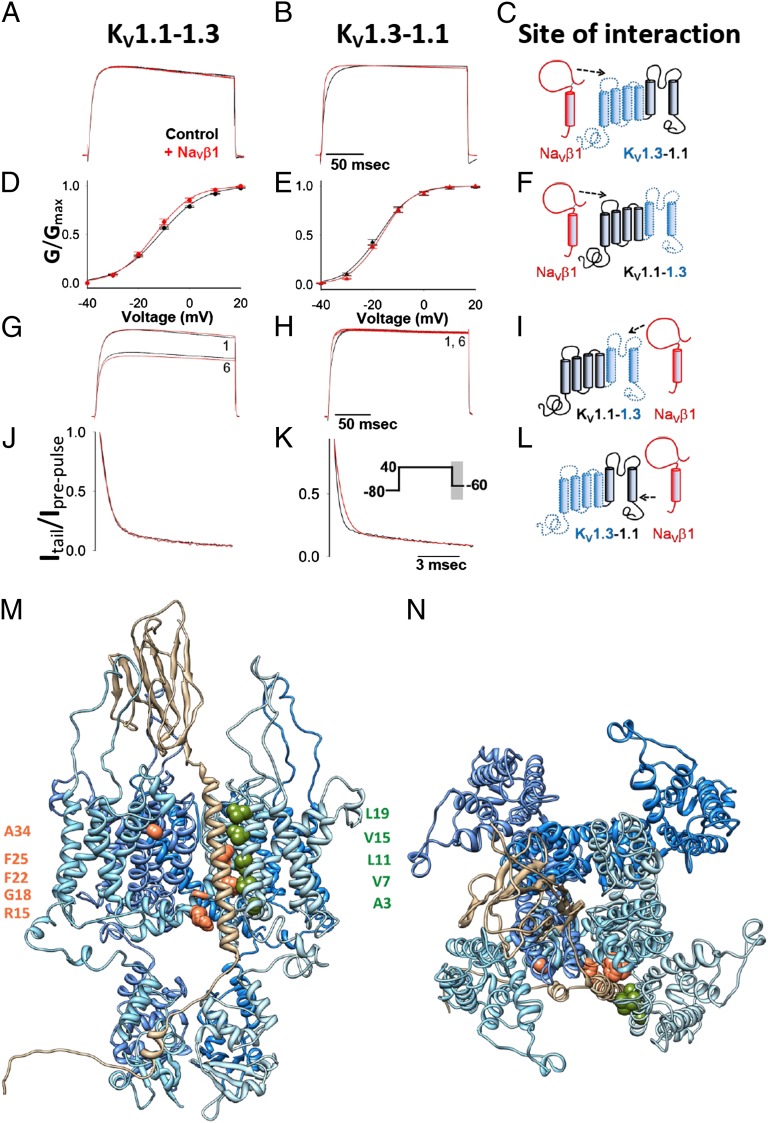

We constructed chimeras of KV1.1 and KV1.3 to identify channel regions required for NaVβ1-mediated modulation. We chose this pair of channels because of the distinctive modulatory effects of NaVβ1. NaVβ1 sped up activation and decreased cumulative inactivation of KV1.3, whereas it had no effect on KV1.1’s activation and inactivation (Fig. 2, Table S1). NaVβ1 shifted the voltage dependence of activation of KV1.1 in a hyperpolarizing direction and it slowed deactivation (τfast at −60 mV) of KV1.1, but did not alter these properties in KV1.3 (Fig. 2, Table S1). The KV1.1–KV1.3 chimera contains the voltage-sensing domain (VSD) of KV1.1 (S1–S4) and the pore domain (PD) of KV1.3 (S5–P–S6), whereas the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimera contains the VSD of KV1.3 and the PD of KV1.1 (Fig. S6). Both chimeras produced robust currents (Fig. 4 A and B). Cumulative inactivation, a unique property of the KV1.3 PD, was exhibited by the KV1.1–KV1.3 chimera but not by the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimera (Fig. 4 G and H), indicating that both chimeras function as predicted.

Fig. 4.

Activation kinetics (A and B), voltage dependence of activation (D and E; mean ± SEM), cumulative inactivation (G and H), and deactivation of KV1.1–KV1.3 and the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimeras (J and K), expressed alone (black) or with NaVβ1 (red) in Xenopus oocytes. Schematic showing interaction between NaVβ1 and domains within the channel chimeras (C, F, I, and L). Current traces shown are averages of normalized currents of selective sample currents of comparable amplitudes. Side view (M) and view from the extracellular side of the membrane (N) of the model of the complex of KV1.2 with NaVβ1. The channel monomers are colored in four different shades of blue, NaVβ1 in tan, and residues that are lipid exposed on the S1 and S5 segments and that differ in character to equivalent residues in other KV channel families are displayed as green and orange spheres, respectively.

The VSD of KV1.3 is required for NaVβ1-mediated acceleration of KV1.3 activation because the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimera (containing KV1.3’s VSD) exhibited faster activation in the presence of NaVβ1, whereas the activation of the KV1.1–KV1.3 chimera (containing KV1.3’s PD) was unaffected by NaVβ1 (Fig. 4C, Table S1). The PD of KV1.3 is required for NaVβ1-mediated reduction of KV1.3 cumulative inactivation because NaVβ1 reduced cumulative inactivation of the KV1.1–KV1.3 chimera (containing KV1.3’s PD), but not the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimera (containing KV1.3’s VSD) (Fig. 4 G and H).

The VSD of KV1.1 is required for the NaVβ1-mediated change in the voltage dependence of KV1.1 activation because the KV1.1–KV1.3 chimera (which contains KV1.1’s VSD), but not the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimera (which contains KV1.1’s PD), exhibited a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation in the presence of NaVβ1 (Fig. 4 D and E, Table S1). The PD of KV1.1 is required for NaVβ1-mediated slowing of KV1.1 deactivation because the KV1.3–KV1.1 chimera (KV1.1’s PD), but not the KV1.1–KV1.3 chimera (KV1.1’s VSD), showed slower deactivation in the presence of NaVβ1 (Fig. 4 J and K).

To examine whether the interaction between NaVβ1 and the KV1.3's PD sterically hinders toxin access to the external channel vestibule, we measured the affinity of the channel for ShK-186, a KV1.3-selective peptide inhibitor (29). ShK-186 blocked KV1.3 in a dose-dependent manner and its potency did not change in the presence of NaVβ1 (Fig. S7). This result suggests that the NaVβ1–KV1.3 interaction does not alter toxin access to the channel vestibule. Overall, these results demonstrate that NaVβ1 accelerates KV1.3 activation by interacting with the KV1.3's VSD, affects cumulative inactivation of KV1.3 through an interaction with KV1.3’s PD, induces a hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of activation of KV1.1 via an interaction with the KV1.1's VSD, and slows deactivation of KV1.1 via an interaction with KV1.1’s PD.

Molecular Modeling.

Docking of full-length NaVβ1 with the KV1.2 homotetramer resulted in a model in which the transmembrane segment of NaVβ1 lies in the groove between the VSD and PD of KV1.2, making significant contacts with the channel’s S1 and S5 segments (Fig. 4 M and N). An alignment of the S5 segments shows several key differences between NaVβ1-resistant KV3.1 and NaVβ1-modulated channels (Fig. S8A). The transmembrane segment of NaVβ1 makes contact with many of the key S5 residues. Several highly conserved residues on NaVβ1 make contact with the channel. Leu13 and Leu17 of NaVβ1 (transmembrane numbering; Fig. S8B) form a pocket into which Phe25 of the KV1.2-S5 segment binds. Trp20 of NaVβ1 packs against Gly18 of the S5 segment, and Glu24 of NaVβ1 forms hydrogen bonds with the uncapped N-terminal main-chain amides of the slide helix (Fig. S8A). Residues of the S1 segment predicted to interact with NaVβ1 include Ala3, Val7, Leu11, Val15, and Leu19 (S1 numbering; Fig. S8C). Val15’s side chain packs against the side chain of Tyr11 of the transmembrane segment of NaVβ1. In the S1 segment, KV3 channels differ significantly from KV1 channels at position 15 (V/T), from Kv4 channels at positions 3 (Y/A), 7 (G/L), 11 (A/L), and 15 (I/T), and from Kv7 channels at positions 3 (Y/A) and 15 (L/T). The Ig domain of NaVβ1 forms extensive interactions with the S1–S2, S5–P, and P–S6 extracellular loops of the channel (Fig. 4 M and N).

Discussion

The precision of neuronal action potential generation and propagation is controlled by the sequential activation and inactivation of NaV and KV channels. In the CNS, four NaV α subunits (NaV1.1–NaV1.3, NaV1.6) in tight complex with NaVβ1–NaVβ4 subunits underlie the depolarization phase of the action potential. Several subfamilies of KV channels are important contributors to action potential repolarization (1–4). NaVβ1, although considered to be a subunit of NaV channels, was recently shown to interact with and modulate the function of KV4 channels in the heart and brain (13–15). Here, we demonstrate that NaVβ1 is a promiscuous protein that can also interact with and modulate the properties of KV1 (KV1.1, KV1.2, KV1.3, KV1.6) and KV7 (KV7.2) channels. Of the channels tested, only KV3.1 was not affected by NaVβ1. Modulation occurs in a channel isoform-specific manner. Through structure–function approaches, we identify regions of NaVβ1 and KV channels required for NaVβ1-dependent modulation, and we provide a model of the NaVβ1 and KV channel complex.

NaVβ1 coassembles with KV1.2, speeds up its activation, shifts its voltage dependence of activation by 4 mV in the hyperpolarized direction, and slows its deactivation in mammalian cells and in Xenopus oocytes. NaVβ1 and KV1.2 colocalize in the axon initial segment in the mouse cerebral cortex where the interaction between the two proteins may affect neuronal excitability. NaVβ1 shifts the voltage dependence of activation of KV1.1 in the hyperpolarized direction, slows deactivation (τfast), and has no effect on activation kinetics. NaVβ1 accelerates activation of KV1.3, abolishes cumulative inactivation (accelerates recovery from C-type inactivation) and has no effect on its voltage dependence of activation or deactivation kinetics. NaVβ1 slows KV1.6 activation, shifts its voltage dependence of activation in a depolarized direction, and significantly increases the amplitude of the KV1.6 tail current without affecting its deactivation kinetics. Another KV channel found in the axon initial segment in the brain, KV7.2, coassembles with NaVβ1 in mammalian cells and its activation is slowed at moderate depolarizing potentials. However, NaVβ1 does not alter activation or deactivation kinetics, or the voltage dependence of activation of the KV3.1 channel.

We used chimeras of NaVβ1 and P0 to define regions in NaVβ1 responsible for KV channel modulation. The NaVβ1 domains required for channel modulation varied in an isoform-specific manner. The external Ig domain of NaVβ1 is solely responsible for modulation of KV1.3, whereas the entire NaVβ1 protein is required to modulate KV1.2 and KV1.1. Chimeras of KV1.3 and KV1.1 were used to identify channel regions required for NaVβ1-mediated modulation. The PD (S5–P–S6) of KV1.3 is required for NaVβ1’s modulation of cumulative inactivation, whereas its VSD (S1–S4) is essential for NaVβ1-mediated acceleration of KV1.3 activation. The PD of KV1.1 is required for NaVβ1’s slowing of deactivation, whereas the VSD is essential for the NaVβ1-mediated hyperpolarizing shift in KV1.1’s voltage dependence of activation.

The model of NaVβ1 docked with KV1.2 permits an interpretation of the isoform-specific properties of the different channels at the level of sequence-specific interactions. All of the NaVβ1-sensitive KV channels contain Leu at position 17 in place of a Phe in KV3 channels (numbering based on Fig. S8A), an aromatic residue (Phe or Tyr) at position 22 in place of Ile, and an Ile at position 29 in place of Leu. The increased bulk and hydrophobic interactions of KV3’s Phe17, and the decreased bulk of KV3’s Ile22, and the loss of hydrophobic interactions between the side chain of Phe/Trp22 (in KV1, KV4, KV7 channels) with NaVβ1, likely impacts the interaction between KV3 and NaVβ1. Trp20 of NaVβ1 packs against Gly18 of the S5 segment; this residue is Leu in the KV3 family. The increased bulk of the side chain of Leu likely impacts the interaction between the proteins. Phe25 of the S5 segment of KV1.2 fits into a pocket formed by two Leu residues (Leu13, -17) of NaVβ1; the smaller Ala present in KV3 channels may pack less well into this pocket and thereby affect binding affinity. The side chain of Val15 of the S1 segment of KV1.2 packs against the side chain of Tyr11 of the transmembrane domain of NaVβ1. Substitution of the hydrophobic Val15 with Thr in KV3 will impact the interaction. Therefore, KV3.1’s resistance to NaVβ1 modulation may be because residues in its S1 and S5 hinder optimal interaction with NaVβ1.

In conclusion, our results provide a structural basis for a NaVβ1-mediated regulation of KV1, KV4, and KV7 channels. By modulating CNS potassium currents, NaVβ1’s importance in channel gating-modulation is extended beyond its influence on NaV currents. Our results provide a mechanism for coordinated control of two important classes of ion channels that underlie neuronal excitability.

Materials and Methods

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell patch-clamp and two-electrode voltage-clamp techniques were used for analysis of mammalian cells and Xenopus oocytes, respectively. Details are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Expression Plasmids, Immunohistochemistry, Coprecipitation, Western Blots, and Molecular Modeling.

Expression plasmids, immunohistochemistry, coprecipitation, Western blots, and molecular modeling are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture and Transfections.

L929 cells stably expressing KV1.2, KV1.3, and KV3.1, CHO cells, and PC12 cells were maintained in standard DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FCS (Summit Biotechnology), 4 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 500 μg/mL G418 (Calbiochem) as described in SI Materials and Methods. Transient transfections were carried out using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 24–30 h, transfection efficiency was assessed by fluorescence microscopy (Olympus).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. K. Mathew (National Centre for Biological Sciences) for expression constructs of KV1.1, KV1.2, and KV1.6 channels; Radit Aur (University of California, Irvine) for preparing the oocytes; Dr. Lori Isom (University of Michigan) for myelin P0, His6-V5-tagged NaVβ1, NaVβ1-P0 chimera, P0-NaVβ1 chimera; and Dr. Jeffrey Calhoun (University of Michigan) for verifying the sequence of the chimeras. A generous allocation of computational resources from the Victorian Life Science Computing Initiative is acknowledged (to B.J.S.). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS48252 (to K.G.C.), NS048336 (to A.L.G.), and NS067288 (to N.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1209142109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(4):397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luján R. Organisation of potassium channels on the neuronal surface. J Chem Neuroanat. 2010;40(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vacher H, Mohapatra DP, Trimmer JS. Localization and targeting of voltage-dependent ion channels in mammalian central neurons. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(4):1407–1447. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brackenbury WJ, Isom LL. Na channel β subunits: Overachievers of the ion channel family. Front Pharmacol. 2011;2:53. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2011.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyama F, et al. Sodium channel beta4 subunit: Down-regulation and possible involvement in neuritic degeneration in Huntington’s disease transgenic mice. J Neurochem. 2006;98(2):518–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyazaki H, et al. BACE1 modulates filopodia-like protrusions induced by sodium channel beta4 subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheffer IE, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy and GEFS+ phenotypes associated with SCN1B mutations. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 1):100–109. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas PT, Meadows LS, Nicholls J, Ragsdale DS. An epilepsy mutation in the beta1 subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel results in reduced channel sensitivity to phenytoin. Epilepsy Res. 2005;64(3):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audenaert D, et al. A deletion in SCN1B is associated with febrile seizures and early-onset absence epilepsy. Neurology. 2003;61(6):854–856. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000080362.55784.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patino GA, et al. A functional null mutation of SCN1B in a patient with Dravet syndrome. J Neurosci. 2009;29(34):10764–10778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2475-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meadows LS, et al. Functional and biochemical analysis of a sodium channel beta1 subunit mutation responsible for generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus type 1. J Neurosci. 2002;22(24):10699–10709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10699.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wallace RH, et al. Febrile seizures and generalized epilepsy associated with a mutation in the Na+-channel beta1 subunit gene SCN1B. Nat Genet. 1998;19(4):366–370. doi: 10.1038/1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marionneau C, et al. The sodium channel accessory subunit Navβ1 regulates neuronal excitability through modulation of repolarizing voltage-gated K+ channels. J Neurosci. 2012;32(17):5716–5727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6450-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deschênes I, Tomaselli GF. Modulation of Kv4.3 current by accessory subunits. FEBS Lett. 2002;528(1-3):183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deschênes I, Armoundas AA, Jones SP, Tomaselli GF. Post-transcriptional gene silencing of KChIP2 and Navbeta1 in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes reveals a functional association between Na and Ito currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45(3):336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grissmer S, et al. Pharmacological characterization of five cloned voltage-gated K+ channels, types Kv1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 3.1, stably expressed in mammalian cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45(6):1227–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rasband MN, Trimmer JS, Peles E, Levinson SR, Shrager P. K+ channel distribution and clustering in developing and hypomyelinated axons of the optic nerve. J Neurocytol. 1999;28(4-5):319–331. doi: 10.1023/a:1007057512576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black JA, Waxman SG, Smith KJ. Remyelination of dorsal column axons by endogenous Schwann cells restores the normal pattern of Nav1.6 and Kv1.2 at nodes of Ranvier. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 5):1319–1329. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devaux JJ, Scherer SS. Altered ion channels in an animal model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type IA. J Neurosci. 2005;25(6):1470–1480. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3328-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoshi T, Aldrich RW. Voltage-dependent K+ currents and underlying single K+ channels in pheochromocytoma cells. J Gen Physiol. 1988;91(1):73–106. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conforti L, Millhorn DE. Selective inhibition of a slow-inactivating voltage-dependent K+ channel in rat PC12 cells by hypoxia. J Physiol. 1997;502(Pt 2):293–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.293bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu Y, Barry J, McDougel R, Terman D, Gu C. Alternative splicing regulates kv3.1 polarized targeting to adjust maximal spiking frequency. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(3):1755–1769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Espinosa F, Torres-Vega MA, Marks GA, Joho RH. Ablation of Kv3.1 and Kv3.3 potassium channels disrupts thalamocortical oscillations in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28(21):5570–5581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0747-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song P, et al. Acoustic environment determines phosphorylation state of the Kv3.1 potassium channel in auditory neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(10):1335–1342. doi: 10.1038/nn1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown DA, Passmore GM. Neural KCNQ (Kv7) channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(8):1185–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lemke G, Axel R. Isolation and sequence of a cDNA encoding the major structural protein of peripheral myelin. Cell. 1985;40(3):501–508. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isom LL, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of the beta 1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science. 1992;256(5058):839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1375395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCormick KA, Srinivasan J, White K, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. The extracellular domain of the beta1 subunit is both necessary and sufficient for beta1-like modulation of sodium channel gating. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(46):32638–32646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.46.32638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cahalan MD, Chandy KG. The functional network of ion channels in T lymphocytes. Immunol Rev. 2009;231(1):59–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.