Abstract

Lanthionine-containing peptides (lanthipeptides) are a family of ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides containing (methyl)lanthionine residues. Here we present a phylogenomic study of the four currently known classes of lanthipeptide synthetases (LanB and LanC for class I, LanM for class II, LanKC for class III, and LanL for class IV). Although they possess very similar cyclase domains, class II–IV synthetases have evolved independently, and LanB and LanC enzymes appear to not always have coevolved. LanM enzymes from various phyla that have three cysteines ligated to a zinc ion (as opposed to the more common Cys-Cys-His ligand set) cluster together. Most importantly, the phylogenomic data suggest that for some scaffolds, the ring topology of the final lanthipeptides may be determined in part by the sequence of the precursor peptides and not just by the biosynthetic enzymes. This notion was supported by studies with two chimeric peptides, suggesting that the nisin and prochlorosin biosynthetic enzymes can produce the correct ring topologies of epilancin 15X and lacticin 481, respectively. These results highlight the potential of lanthipeptide synthetases for bioengineering and combinatorial biosynthesis. Our study also demonstrates unexplored areas of sequence space that may be fruitful for genome mining.

Keywords: molecular evolution, natural products, phylogeny, posttranslational modification, lantibiotics

Peptide antibiotics represent a large and diverse group of bioactive natural products with a wide range of applications. Most of these compounds are produced via two distinct biosynthetic paradigms. The nonribosomal peptide synthetases are responsible for the biosynthesis of many clinically important antibiotics (1, 2). A different strategy involves posttranslational modifications of linear ribosomally synthesized peptides (3, 4). This biosynthetic strategy is also widely distributed and found in all three domains of life. Although the building blocks used by ribosomes are generally confined to the 20 proteinogenic amino acids, the structural diversity generated by posttranslational modifications is vast (5).

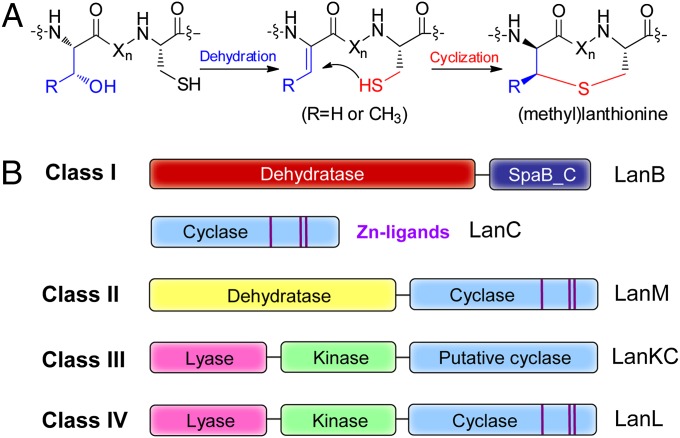

Among the best-studied ribosomally synthesized and posttranslationally modified peptides are the lanthipeptides, a class of compounds distinguished by the presence of sulfur-to-β–carbon thioether cross-links named lanthionines and methyllanthionines (Fig. 1) (6–9). Many lanthipeptides, such as the commercially used food preservative nisin, have potent antimicrobial activity and are termed lantibiotics. Maturation of lanthipeptides involves posttranslational modifications of a C-terminal core region of a precursor peptide and subsequent proteolytic removal of an N-terminal leader sequence that is not modified (3). Their thioether bridges are installed by the initial dehydration of Ser and Thr residues, followed by stereoselective intramolecular Michael-type addition of Cys thiols to the newly formed dehydroamino acids (Fig. 1A). In some cases, this reaction is coupled with a second Michael-type addition of the resulting enolate to a second dehydroalanine to produce a labionin structure (10). Genetic and biochemical studies have revealed four distinct classes of lanthipeptides according to their biosynthetic machinery (7, 11, 12) (Fig. 1B). Class I lanthipeptides are synthesized by two different enzymes, a dehydratase LanB, and a cyclase LanC (Lan is a generic designation for lanthipeptide biosynthetic proteins). For class II lanthipeptides, the reactions are carried out by a single lanthipeptide synthetase, LanM, containing an N-terminal dehydratase domain that bears no homology to LanB, and a C-terminal LanC-like cyclase domain. Class III and class IV lanthipeptides are synthesized by trifunctional enzymes LanKC (10, 13) and LanL (12), respectively. These enzymes contain an N-terminal lyase domain and a central kinase domain but differ in their C termini. LanC and the C-terminal domains of LanM and LanL contain a conserved zinc-binding motif (Cys-Cys-His/Cys), whereas the C-terminal cyclase domain of LanKC lacks these conserved residues (13) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Biosynthesis of lanthipeptides, showing the mechanism of (methyl)lanthionine formation (A), and the four classes of synthetases (B). Xn represents a peptide linker. The conserved zinc-binding motifs are highlighted by the purple lines in the cyclase domains. SpaB_C is an in silico defined domain currently found as a stand-alone protein for thiopeptide biosynthesis and as the C-terminal domain of LanB enzymes. The N-terminal domain of LanB enzymes is made up of two subdomains according to the Conserved Domain Database (26).

Recent genome mining studies have revealed that lanthipeptide biosynthetic genes are present in a wide range of bacteria (14–16). The widespread occurrence may not be surprising, given the potential benefits of gene-encoded natural products with respect to facile evolution of new structures and biological function. Here we present a systematic analysis of the phylogenetic distribution of lanthipeptide synthetases. We correlate the taxonomy of the bacterial host and the structure of the final products with the enzyme phylogenies. Implications for biosynthetic engineering of the lanthipeptide family and for genome mining are discussed.

Results and Discussion

Evolution of LanC enzymes.

LanCs have about 400 amino acid residues, and possess a double α–barrel-fold topology (17) and a strictly conserved Cys-Cys-His triad near their C termini for binding of a zinc ion. In vitro reconstitution of the nisin cyclase activity of NisC and solution of its crystal structure have supported a zinc-dependent mechanism (17, 18). The zinc ion is believed to activate the Cys thiols of the precursor peptide for nucleophilic attack on the dehydroamino acids. LanC or LanC-like enzymes are not only found as stand-alone cyclases and as cyclase domains in LanM and LanL enzymes, their encoding genes are also present in eukaryotes, although the detailed functions of these LanC-like (LanCL) proteins remain to be determined (19).

The phylogeny of LanC from different bacterial lineages, including the C-terminal domains of LanMs and LanLs, and the LanCL proteins from human that can serve as the outgroup, was constructed using both Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) (20) and maximum-likelihood inferences (21). To obviate codon bias, the trees were constructed based on amino acid sequences instead of nucleic acid sequences. The overall Bayesian MCMC tree shown in Fig. 2 A and B is almost exactly the same with that prepared by the maximum-likelihood method (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), strongly supporting the reliability of both trees.

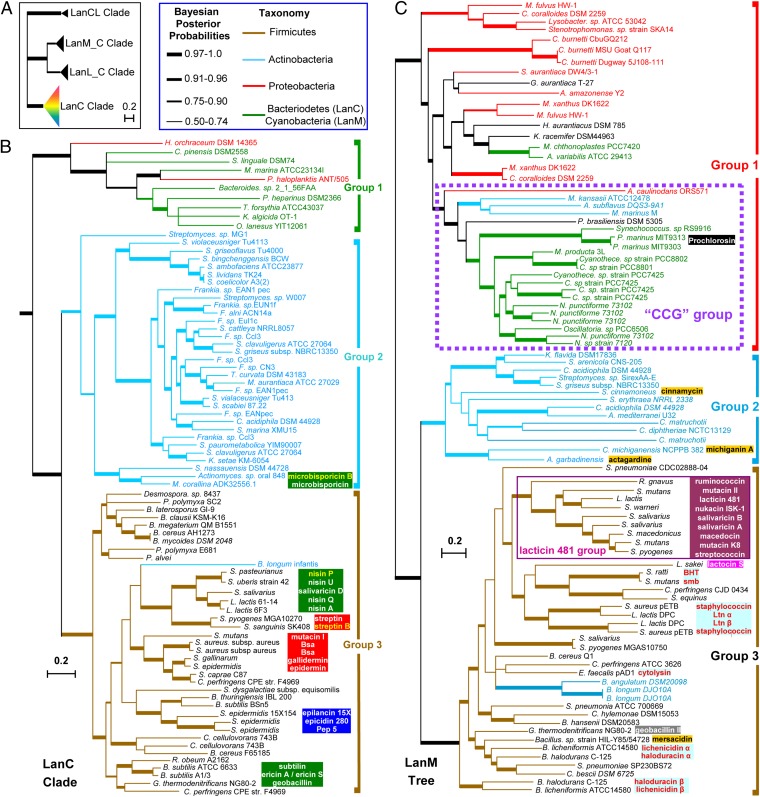

Fig. 2.

Bayesian MCMC phylogeny of LanC and LanM enzymes. (A) Tree of LanC and LanC-like enzymes. LanM_C and LanL_C represent the C-terminal cyclase domains of LanM and LanL, respectively. (B) The LanC clade of A. (C) Phylogenetic tree of LanM enzymes. As no suitable outgroup protein can be found (LanLs cannot serve as outgroup, because their N-terminal domains are not homologous to those of LanMs), the trees were rooted by using all members of a sister clade as the outgroup, an approach previously suggested as optimal in such instances (44). Bayesian inferences of posterior probabilities are indicated by line width. Lanthipeptides in each tree are shown by different colored boxes according to structural types. Two-component lantibiotics are in red font, and lanthipeptides proposed in this study are in yellow font.

The C-terminal domains of LanM and LanL fall into two distinct clades. These two clades group into a larger clade and are separated from a sister LanC clade and the eukaryotic LanCL clade (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1), suggesting that LanM and LanL evolved independently from LanC. If LanM and LanL originate from hybridization of an ancestral LanC with a dehydratase or kinase, this event likely occurred only once. Gene recombination between the C-terminal domains of LanM and LanL is not supported by our analysis of the currently available sequences.

LanCs from different bacterial phyla group into three groups with strong statistical support (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Group 1 consists of enzymes from bacteroidetes and proteobacteria. Although proteobacteria are a prolific source of LanM enzymes (vide infra), only very few LanCs are found in this phylum. Group 2 and group 3 consist of proteins from actinobacteria and firmicutes, respectively, which group into a larger clade that is sister to group 1, indicating that LanC enzymes from these two phyla are more closely related with each other than with their counterparts from bacteroidetes and proteobacteria. Group 3 consists of the enzymes from firmicutes, with only one exception of an enzyme from Bifidobacterium longum, which belongs to the actinobacteria. Taken together, these results indicate that LanCs from different phyla have evolved independently, and that interphylum horizontal gene transfer generally did not occur during LanC evolution.

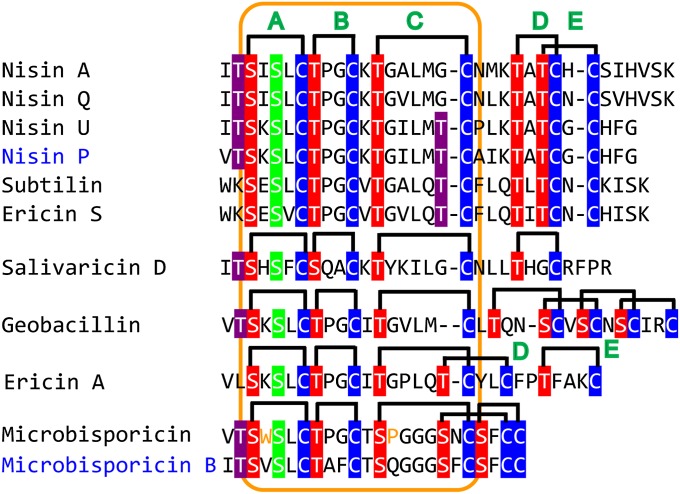

Class I lanthipeptides have been grouped into nisin-like, epidermin-like, and Pep5-like groups (8) (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). Although LanC enzymes for producing structurally similar lanthipeptides usually cluster together (Fig. 2B), this is not always the case. Nisin and subtilin have similar precursor peptide sequences and exactly the same ring topologies (6) (Fig. 3), but their associated LanC enzymes have relatively distant relationships (Fig. 2B). Moreover, microbisporicin has a similar N-terminal structure to that of nisin, but is produced by Actinobacteria (22, 23), and its LanC does not even belong to group 3, which harbors most enzymes for nisin-like lanthipeptides. These results demonstrate convergent evolution to arrive at nisin-like architectures. When also taking into consideration the distinct C-terminal ring topologies of subtilin (6), ericin A (24), and geobacillin (25) (Fig. 3), and their closely related LanCs (Fig. 2B), the ring topology of some lanthipeptides may be determined as much by the sequence of their precursor peptides as by their cyclase sequences. This hypothesis could have important implications for bioengineering (vide infra). Conversely, it is puzzling that thus far the potent lipid II binding topology of the A and B rings of the nisin-like peptides has only been observed in class I compounds and not in the other classes of lanthipeptides.

Fig. 3.

Comparative analysis of the nisin-like peptides. A–E denote different rings. The conserved N termini are highlighted by the orange box. Ser and Thr that are involved in ring formation are shown by red highlighted font. Ser and Thr that are dehydrated but not involved in ring formation are shown in green and purple highlighted font. New compounds proposed in this study are shown in blue font.

Evolution of LanB enzymes.

LanB proteins usually have about 1,000 residues, consisting of a lanthipeptide dehydratase domain and a so-called SpaB_C (SpaB C-terminal) domain (26) (Fig. 1B). A few lanthipeptide biosynthetic gene clusters contain genes encoding a C-terminally truncated LanB and a stand-alone SpaB_C-like protein, suggesting that the two domains of LanB might be able to act both in cis and in trans. Similarly, most of the thiopeptide biosynthetic gene clusters encode two proteins for dehydration: a putative dehydratase that shares low sequence similarity with LanBs and a SpaB_C-like protein (27). In this study, only full-length LanB sequences were used.

The phylogenetic trees of LanB enzymes from the same gene cluster as the LanC proteins in Fig. 2B were constructed by both Bayesian MCMC and maximum-likelihood methods, and the resulting two trees are almost identical (SI Appendix, Figs. S4 and S5). Interestingly, the topology of the LanB tree is distinct from that of LanC. The enzymes from bacteroidetes and proteobacteria are possibly derived from firmicutes because they are deeply nested within a group that mainly consists of LanBs from firmicutes (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This finding is in distinct contrast to the LanC tree in which the enzymes of group 1 are distantly related to those of group 3 (Fig. 2B). It appears therefore that for these clusters, LanBs have evolved independently from LanCs, or that the LanBs or LanCs may have been recruited from other organisms and have formed a functional pair. In general, however, the trees show that LanB and LanC enzymes from the same organism fall into similar clades (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S4), suggesting that they have coevolved.

Genome mining for new class I lanthipeptides might be facilitated by phylogenetic categorization of LanC and LanB enzymes. For example, we note that Streptococcus pasteurianus contains genes for LanB and LanC that are phylogenetically closely related to NisB and NisC (Fig. 2). Examining their associated lanA gene suggests that this strain may be able to produce a nisin analog similar to nisin U (designated nisin P in Fig. 3). Similarly, Actinomyces sp. oral may produce a microbisporicin analog (designated microbisporicin B in Fig. 3), and Streptococcus sanguinis may produce a streptin analog (designated streptin B in SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Given the vast sequence space of uncharacterized enzymes from strains other than firmicutes (e.g., group 1 and group 2 in Fig. 2B), these data may also serve as a guideline for future genome mining efforts.

Evolution of LanM Enzymes.

LanMs are bifunctional enzymes of 900–1,200 residues containing an N-terminal dehydratase and a C-terminal LanC-type cyclization domain (7, 28). LanM proteins use ATP to phosphorylate Ser/Thr residues in their substrates and they subsequently eliminate the resulting phosphate ester to yield the dehydroamino acids (29). The C-terminal domain then catalyzes the cyclization reaction in a similar manner to LanC enzymes. Unlike LanBs and LanCs, LanMs are prevalent in proteobacteria and have also been characterized from cyanobacteria (30, 31). However, in our analysis they are not found in bacteroidetes, again indicating that different classes of lanthipeptides likely evolved independently.

Bayesian MCMC and maximum-likelihood trees of 91 LanM sequences from different bacterial phyla were constructed (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). The Bayesian MCMC inference of LanM phylogeny shown in Fig. 2C is similar to that of LanC and LanB, in that enzymes are usually grouped according to their producing organisms and form three major subdivisions. Group 1 is a polyphyletic clade mainly consisting of enzymes from proteobacteria and cyanobacteria. Because the base of group 1 consists exclusively of proteobacterial enzymes (Fig. 2C), members of group 1 from other phyla possibly evolved from proteobacterial ancestors. Groups 2 and 3 are made up of enzymes from actinobacteria and firmicutes, respectively, with the only exceptions enzymes from Bifidobacteria (Fig. 2C), which fall into the firmicutes clade similar to what was observed for LanC (Fig. 2B).

Notably, the enzymes that synthesize type IIA compounds (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) (8, 32) are grouped into a subclade with strong support (Fig. 2C). Type IIA compounds are structurally similar to the prototypical peptide lacticin 481, which possesses a linear N terminus and a globular C-terminal scaffold (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) (6, 32). The close correlation of the enzyme phylogeny and the structure of the final products demonstrate that these products evolved from the same ancestors, in contrast to the apparent convergent evolution of several members of the nisin-like peptides discussed above. Enzymes for synthesizing the two-component lantibiotics are distributed in different subclades of group 3 (Fig. 2C). These systems are potent antimicrobial agents that display strong synergism between the two posttranslationally modified peptides (7–9). Although the two peptides of lacticin 3147 (Ltnα and Ltnβ) have similar ring topologies as haloduracin-α and -β, particularly in their C-terminal regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), their corresponding LanMs are phylogenetically distantly related (Fig. 2C). These results reinforce the idea that the ring topologies of lanthipeptides might be determined to a larger extent than previously anticipated by the sequence of the precursor peptide, as discussed above.

The biosynthesis of the prochlorosins from cyanobacteria represents a remarkable example of natural combinatorial biosynthesis (31): up to 29 different ProcA peptides with highly variable sequences in the core region but highly conserved leader sequences serve as substrates of a single enzyme ProcM, resulting in a library of structurally diverse lanthipeptides (30, 31). This system is a prime example of the highly evolvable nature of ribosomal biosynthesis to access high structural diversity of natural products at low genetic cost. Analysis of the ProcM sequence revealed that this enzyme contains a “CCG” motif (30) rather than a “CHG” motif (17, 18) found in all LanCs and most of the LanMs known to date, indicating that ProcM likely uses three Cys residues rather than a Cys-Cys-His triad for binding of the active site zinc ion. Model studies of activation of thiolate nucleophiles by Zn2+ have demonstrated increased reactivity with an increased number of thiolate ligands (33), suggesting that ProcM may derive its promiscuity in part from a highly active zinc ion (30). Intriguingly, all LanM proteins containing the “CCG” motif cluster together to form a distinct subgroup within group 1 (Fig. 2C). This phylogenetic distribution is not merely a consequence of the “CCG” or “CHG” motifs, because artificially changing Cys to His or His to Cys in the motif for five representative group 1 enzymes did not alter their position in the tree or greatly affect the statistic support of the phylogenetic trees (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Rather, these results suggest that LanMs containing the conserved “CCG” motif have evolved independently from the other LanM proteins. Some but not all of the members of the CCG clade have multiple precursor genes nearby and at other loci of their genomes similar to ProcM.

Evolution of LanKC and LanL enzymes.

LanKC and LanL both contain an N-terminal lyase domain and a central kinase domain, with both enzymes generating dehydroamino acids via independent phosphorylation and elimination steps (7, 12). The C-terminal cyclase domain of LanKC enzymes lacks the conserved residues for binding of a zinc ion. Consistent with this observation, AciKC involved in catenulipeptin biosynthesis binds neither zinc nor other metals, indicating a different cyclization mechanism of LanKC enzymes, but domain deletions support the hypothesis that the C-terminal domain is responsible for cyclization (34). Many, but not all, LanKCs synthesize labionins (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), which are thus far found exclusively for class III lanthipeptides (34–36).

Bayesian MCMC and maximum-likelihood inferences of 39 LanKC sequences and 15 LanL sequences were constructed (SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13). Clearly, LanKC and LanL enzymes group into different clades, indicating that, despite the significant sequence similarities and the similar domain structure, these two enzyme classes have evolved independently. The possibility that LanKCs are derived from LanLs by loss of the zinc-binding site is therefore unlikely. Interestingly, some LanLs contain the “CCG” instead of the “CHG” motif and may have three Cys residues that coordinate to the zinc ion. As was observed for LanMs, these enzymes fall into a distinct subgroup (SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13).

Phylogenetically, there are no obvious distinctions between LanKC enzymes that generate lanthionine and labionin structures. For example, catenulipeptin and labyrinthopeptin contain only labionins (34, 35) and SapB contains only lanthionines (13) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), but catenulipeptide synthetase AciKC is phylogenetically closer to the SapB synthetase RamC than the labyrinthopeptin synthetase LabKC (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). In addition, recently characterized class III peptides contain both lanthionine and labionin (36), and the biosynthetic enzymes of these peptides are distributed in different subclades of the LanKC clade (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Thus, it is possible that the cyclization mode for class III may again be dependent on the precursor peptide sequences.

Determinants of Lanthipeptide Ring Topologies.

The ring systems of lanthipeptides are very diverse, ranging from simple nonoverlapping rings to highly complex, intertwined rings (SI Appendix, Figs. S2, S3, and S9). The possibility to form labionin rings further diversifies lanthipeptide ring systems. The manner by which ring topology is determined from precursor peptides containing multiple Cys and Ser/Thr residues is at present entirely unclear. As discussed above, the trees provide several examples of enzymes that produce structurally similar lanthipeptides falling into different phylogenetic clades, as well as phylogenetically closely related enzymes generating products with distinct rings. These results suggest that in some cases, the substrate sequences may be as important to determine the ring topologies of the final product as the cyclization enzymes.

The notion of substrate-directed ring patterns is supported by comparative analysis of the nisin-group (Fig. 3). All members of this group contain a conserved N-terminal ring system, but their biosynthetic enzymes fall into three different clades (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, ericin S and A, despite possessing very different C-terminal ring topologies, are produced by the same biosynthetic enzymes (24). The D-ring of ericin S is linked to the E-ring in similar fashion as in nisin, whereas the D-ring of ericin A is intertwined with the C-ring, similar to that found in microbisporicin (Fig. 3). This analysis supports a more prominent role of the substrate sequences. Remarkably, Kuipers and colleagues have recently shown that the precursors of a class II two-component lantibiotic can be modified by the nisin biosynthetic enzymes to form antimicrobially active products (37). Although the structures are currently unknown, the products likely have the same or very similar ring topologies as the wild-type peptides, supporting the importance of substrate sequence in the ring-pattern formation.

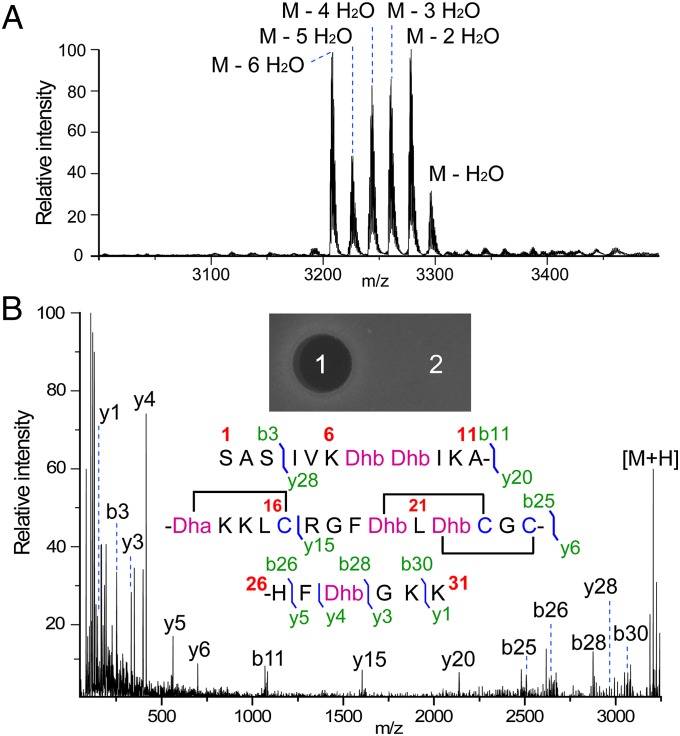

To further address this hypothesis, we generated a construct encoding a chimeric peptide NisA-ElxA, in which the leader sequence of the nisin precursor peptide (NisA) was fused to the core peptide of epilancin 15X separated by an engineered glutamic acid residue for proteolytic removal of the leader peptide. Nisin and epilancin 15X have very different N termini but similar C termini (SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3). Coexpression of NisA-ElxA with NisB and NisC in Escherichia coli resulted in a series of products that were dehydrated up to six times compared with eight dehydrations in epilancin 15X (Fig. 4A). Electron spray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS analysis suggested that the two N-terminal Ser residues escaped dehydration in the sixfold dehydrated peptide and that it very likely has the same ring pattern as that of epilancin 15X (Fig. 4B). Indeed, proteolytic removal of the leader peptide with endoproteinase GluC and subsequent use of the product for well-diffusion assays clearly demonstrated a zone of growth inhibition of the indicator strain Staphylococcus carnosus (Fig. 4B). The product from a parallel experiment in which NisC was not coexpressed lacked antibacterial activity.

Fig. 4.

Generation of a bioactive epilancin 15X analog with the nisin biosynthetic enzymes. (A) MALDI-MS analysis of NisA-ElxA modified in E. coli by NisB and NisC and treated with GluC protease. (B) ESI-MS/MS analysis of the sixfold dehydrated peptide. The proposed structure, the MS/MS fragmentation pattern, and the in vitro bioassay against S. carnosus are shown. Spots 1 and 2 on the bioassay plate are assay and negative control.

To extend these studies to chimera of lanthipeptides that have no structural similarity, we fused the lacticin 481 core peptide to the ProcA3.2 leader sequence to afford a chimeric peptide ProcA-LctA. This peptide was coexpressed in E. coli with the highly promiscuous enzyme ProcM. MS analysis showed that the peptide was dehydrated up to five times (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A). Iodoacetamide alkylation assays and ESI-MS/MS analysis indicated that the products contained a mixture of peptides that were partially and fully cyclized (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 B and C). Intriguingly, after removal of the ProcA leader peptide, the resultant product was active against the indicator strain Lactococcus lactis HP (SI Appendix, Fig. S14D), collectively suggesting that the correct rings of lacticin 481 were produced. These results support a model in which the Cys residues lodge onto the Zn2+ ion in the active site and that subsequently the precursor peptide sequence determines the site selectivity of cyclization. In other words, the cyclase does not appear to enforce the rings to be generated, nor do initially formed rings govern the site selectivity of subsequently formed rings. The latter point is also supported by previous studies on single-ring disruptions of haloduracin (38). To emphasize that not all synthetases can make every lanthipeptide, ProcM did not process a chimeric peptide consisting of the ProcA leader and NisA core peptides to a bioactive product (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Possibly, incomplete dehydration precluded formation of the correct rings.

Base Composition and Codon Use of Lanthipeptide Synthetase Genes.

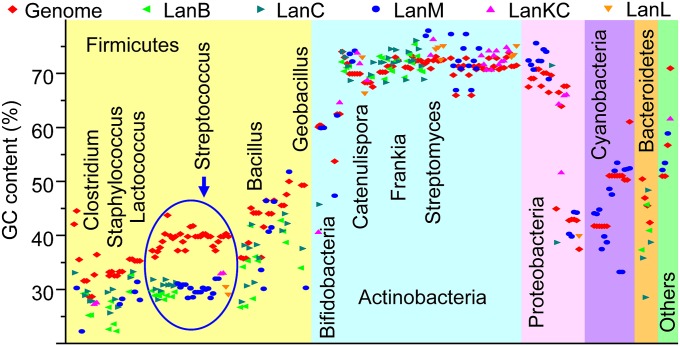

Base composition analysis is a common strategy to investigate gene history and potential horizontal gene transfer events (39, 40). If a gene is a vertical descendent, it should have a similar base composition as the host genome, whereas if it does not, the gene is likely acquired relatively recently from another organism. We calculated the GC content of every lanthipeptide synthetase gene for which complete genome sequences are available and compared the results with the GC content of their genomes (Fig. 5). The analysis shows that enzymes from actinobacteria usually have nucleotide composition similar to their genomes, with exceptions again found for Bifidobacteria. The GC content of lanC and lanKC genes from this genus strongly deviate from their genomes, indicating these genes were most likely acquired by recent horizontal gene transfer. Genes of lanthipeptide synthetases from firmicutes show substantial variations of nucleotide base composition (Fig. 5). A notable example involves the genes from Geobacillus, with GC contents that are decreased significantly compared with their genomes. Taken together with the phylogenetic results, these genes were likely acquired horizontally from Bacillus strains (Fig. 2 B and C). Application of other methods to investigate nucleotide use in lanthipeptide biosynthetic genes, including GC3s and the effective number of codons (Nc) (41), indicates that our analysis is not biased by the codon preference of different organisms (SI Appendix, Fig. S16).

Fig. 5.

Base composition analysis of the lanthipeptide synthetase genes and the associated genomes. Genome sequences are from the same species as the synthetase genes but the subspecies are different in some cases.

All lanthipeptide biosynthetic genes from Streptococci have relatively low GC contents (Fig. 5). To evaluate the significance of these high deviations, for every Streptococcus strain of Fig. 5, we selected 25 genes believed to be less prone to horizontal gene transfer (42) and calculated their GC composition and overall SDs (σ) (SI Appendix, Table S1). This analysis indicates that the σ values of the core genes for all strains are lower than 3% (SI Appendix, Table S1), whereas the majority of the streptococcal lanthipeptide synthetase genes have GC contents decreased by more than 4σ from their genome, suggesting that they were likely acquired recently by horizontal gene transfer.

Conclusion

The knowledge of the chemical and biosynthetic diversity of ribosomal natural products has been greatly expanded in recent years. These compounds are distinct from other well-established natural products because they are gene-encoded and their structures can be easily changed by simple permutation of the precursor peptide sequences. Using lanthipeptide synthetases as a model system, the phylogenomic studies represented herein indicate a complex, dynamic, and sometimes convergent evolution mechanism of the biosynthetic enzymes. Several interesting observations are made, such as mostly phylum-dependent groupings, the clustering of subgroups of enzymes that differ in the identity of a single metal ligand, and the possibility that precursor peptide sequence may be a larger determinant of final ring topology than previously recognized. This hypothesis is supported by experimental studies with chimeric peptides showing that phylogenetically distantly related enzymes can produce the same ring topologies given the same peptide sequence. The phylogenetic trees described herein can also direct future genome mining studies, as they show that some biosynthetic sequence space has not been tapped at all, whereas other areas have been heavily sampled. These findings may also serve as an entry point for understanding the evolutionary mechanism of other ribosomal natural products.

Materials and Methods

Bayesian MCMC inference analyses were performed using the program MrBayes (version 3.2) (43). Final analyses consisted of two sets of eight chains each (one cold and seven heated), run for about 2–10 million generations with trees saved and parameters sampled every 100 generations. Analyses were run to reach a convergence with SD of split frequencies < 0.01. Posterior probabilities were averaged over the final 75% of trees (25% burn in). For additional details of phylogenetic analysis, procedures for the studies with the chimeric peptides, expression and purification of modified peptide products, MS and bioactivity assays, and nucleotide base composition and codon use analysis, please see the SI Appendix. The SI Appendix also contains the accession number and the source organism of the synthetases used (SI Appendix, Tables S2–S5).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Taras Pogorelov and Mike Hallock (University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign) for providing computation and network assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM58822 (to W.A.v.d.V.) and T32 GM070421 (to J.E.V.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210393109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: Logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem Rev. 2006;106(8):3468–3496. doi: 10.1021/cr0503097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strieker M, Tanović A, Marahiel MA. Nonribosomal peptide synthetases: Structures and dynamics. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20(2):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oman TJ, van der Donk WA. Follow the leader: The use of leader peptides to guide natural product biosynthesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(1):9–18. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velásquez JE, van der Donk WA. Genome mining for ribosomally synthesized natural products. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McIntosh JA, Donia MS, Schmidt EW. Ribosomal peptide natural products: Bridging the ribosomal and nonribosomal worlds. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26(4):537–559. doi: 10.1039/b714132g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willey JM, van der Donk WA. Lantibiotics: Peptides of diverse structure and function. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:477–501. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knerr PJ, van der Donk WA. Discovery, biosynthesis, and engineering of lantipeptides. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:479–505. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060110-113521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bierbaum G, Sahl HG. Lantibiotics: Mode of action, biosynthesis and bioengineering. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2009;10(1):2–18. doi: 10.2174/138920109787048616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piper C, Cotter PD, Ross RP, Hill C. Discovery of medically significant lantibiotics. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2009;6(1):1–18. doi: 10.2174/157016309787581075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller WM, Schmiederer T, Ensle P, Süssmuth RD. In vitro biosynthesis of the prepeptide of type-III lantibiotic labyrinthopeptin A2 including formation of a C-C bond as a post-translational modification. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49(13):2436–2440. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pag U, Sahl HG. Multiple activities in lantibiotics—Models for the design of novel antibiotics? Curr Pharm Des. 2002;8(9):815–833. doi: 10.2174/1381612023395439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goto Y, et al. Discovery of unique lanthionine synthetases reveals new mechanistic and evolutionary insights. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(3):e1000339. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kodani S, et al. The SapB morphogen is a lantibiotic-like peptide derived from the product of the developmental gene ramS in Streptomyces coelicolor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(31):11448–11453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsh AJ, O’Sullivan O, Ross RP, Cotter PD, Hill C. In silico analysis highlights the frequency and diversity of type 1 lantibiotic gene clusters in genome sequenced bacteria. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:679. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begley M, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Identification of a novel two-peptide lantibiotic, lichenicidin, following rational genome mining for LanM proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(17):5451–5460. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00730-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haft DH, Basu MK, Mitchell DA. Expansion of ribosomally produced natural products: A nitrile hydratase- and Nif11-related precursor family. BMC Biol. 2010;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li B, et al. Structure and mechanism of the lantibiotic cyclase involved in nisin biosynthesis. Science. 2006;311(5766):1464–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.1121422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, van der Donk WA. Identification of essential catalytic residues of the cyclase NisC involved in the biosynthesis of nisin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(29):21169–21175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong WX, et al. Lanthionine synthetase C-like protein 1 interacts with and inhibits cystathionine beta-synthase: A target for neuronal antioxidant defense. J Biol Chem. 2012 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M1112.383646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mau B, Newton MA, Larget B. Bayesian phylogenetic inference via Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Biometrics. 1999;55(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52(5):696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castiglione F, et al. Determining the structure and mode of action of microbisporicin, a potent lantibiotic active against multiresistant pathogens. Chem Biol. 2008;15(1):22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foulston LC, Bibb MJ. Microbisporicin gene cluster reveals unusual features of lantibiotic biosynthesis in actinomycetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(30):13461–13466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008285107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stein T, et al. Two different lantibiotic-like peptides originate from the ericin gene cluster of Bacillus subtilis A1/3. J Bacteriol. 2002;184(6):1703–1711. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.6.1703-1711.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garg N, Tang W, Goto Y, Nair SK, van der Donk WA. Lantibiotics from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(14):5241–5246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116815109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD: A Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D225–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C, Kelly WL. Recent advances in thiopeptide antibiotic biosynthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27(2):153–164. doi: 10.1039/b922434c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siezen RJ, Kuipers OP, de Vos WM. Comparison of lantibiotic gene clusters and encoded proteins. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69(2):171–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00399422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatterjee C, et al. Lacticin 481 synthetase phosphorylates its substrate during lantibiotic production. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(44):15332–15333. doi: 10.1021/ja0543043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang W, van der Donk WA. Structural characterization of four prochlorosins: A novel class of lantipeptides produced by planktonic marine cyanobacteria. Biochemistry. 2012;51(21):4271–4279. doi: 10.1021/bi300255s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li B, et al. Catalytic promiscuity in the biosynthesis of cyclic peptide secondary metabolites in planktonic marine cyanobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(23):10430–10435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913677107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dufour A, Hindré T, Haras D, Le Pennec JP. The biology of lantibiotics from the lacticin 481 group is coming of age. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2007;31(2):134–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penner-Hahn J. Zinc-promoted alkyl transfer: A new role for zinc. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2007;11(2):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang H, van der Donk WA. Biosynthesis of the class III lantipeptide catenulipeptin. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7(9):1529–1535. doi: 10.1021/cb3002446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meindl K, et al. Labyrinthopeptins: A new class of carbacyclic lantibiotics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49(6):1151–1154. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Völler GH, et al. Characterization of new class III lantibiotics—Erythreapeptin, avermipeptin and griseopeptin from Saccharopolyspora erythraea, Streptomyces avermitilis and Streptomyces griseus demonstrates stepwise N-terminal leader processing. ChemBioChem. 2012;13(8):1174–1183. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Majchrzykiewicz JA, et al. Production of a class II two-component lantibiotic of Streptococcus pneumoniae using the class I nisin synthetic machinery and leader sequence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(4):1498–1505. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00883-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper LE, McClerren AL, Chary A, van der Donk WA. Structure-activity relationship studies of the two-component lantibiotic haloduracin. Chem Biol. 2008;15(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia-Vallvé S, Romeu A, Palau J. Horizontal gene transfer in bacterial and archaeal complete genomes. Genome Res. 2000;10(11):1719–1725. doi: 10.1101/gr.130000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Popa O, Hazkani-Covo E, Landan G, Martin W, Dagan T. Directed networks reveal genomic barriers and DNA repair bypasses to lateral gene transfer among prokaryotes. Genome Res. 2011;21(4):599–609. doi: 10.1101/gr.115592.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright F. The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene. 1990;87(1):23–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daubin V, Gouy M, Perrière G. A phylogenomic approach to bacterial phylogeny: Evidence of a core of genes sharing a common history. Genome Res. 2002;12(7):1080–1090. doi: 10.1101/gr.187002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61(3):539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith AB. Rooting molecular trees—Problems and strategies. Biol J Linn Soc Lond. 1994;51(3):279–292. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.