Abstract

There is an unmet need for circulating biomarkers that can detect early-stage lung cancer. Here we show that a variant form of the nuclear matrix-associated DNA replication factor Ciz1 is present in 34/35 lung tumors but not in adjacent tissue, giving rise to stable protein quantifiable by Western blot in less than a microliter of plasma from lung cancer patients. In two independent sets, with 170 and 160 samples, respectively, variant Ciz1 correctly identified patients who had stage 1 lung cancer with clinically useful accuracy. For set 1, mean variant Ciz1 level in individuals without diagnosed tumors established a threshold that correctly classified 98% of small cell lung cancers (SCLC) and non-SCLC patients [receiver operator characteristic area under the curve (AUC) 0.958]. Within set 2, comparison of patients with stage 1 non-SCLC with asymptomatic age-matched smokers or individuals with benign lung nodules correctly classified 95% of patients (AUCs 0.913 and 0.905), with overall specificity of 76% and 71%, respectively. Moreover, using the mean of controls in set 1, we achieved 95% sensitivity among patients with stage 1 non-SCLC patients in set 2 with 74% specificity, demonstrating the robustness of the classification. RNAi-mediated selective depletion of variant Ciz1 is sufficient to restrain the growth of tumor cells that express it, identifying variant Ciz1 as a functionally relevant driver of cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. The data show that variant Ciz1 is a strong candidate for a cancer-specific single marker capable of identifying early-stage lung cancer within at-risk groups without resort to invasive procedures.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Approximately 80% of lung tumors are classified as nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC), including squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, and the remainder as small cell type (SCLC). SCLCs are primarily neuroendocrine in origin, ranging from low-grade typical carcinoid to high-grade neuroendocrine tumors (HGNTs), although some HGNTs are classified as large cell type (1, 2). The risk of lung cancer is increased dramatically by smoking, and genetic factors appear to play a role in our ability to deal with smoking-related damage. However, clearly heritable forms of increased lung cancer risk are not common. Lung cancer diagnosis and staging relies heavily on imaging, suggesting that imaging may offer a route to early detection in high-risk groups. Although the impact of early detection on survival has been questioned, several studies have looked at the potential benefit (3), and it recently became clear that screening with low-dose spiral CT can achieve a significant reduction in mortality among heavy smokers (4). However, because around a quarter of individuals require follow-up procedures to investigate suspicious imaging results, the cost of this approach is extremely high, highlighting the need for a second-line noninvasive test that can confirm malignancy. Here we present evidence that protein-level detection of a variant form of the nuclear matrix protein Ciz1 has the potential to meet this need. Ciz1 promotes initiation of mammalian DNA replication, where it helps coordinate the sequential functions of cyclin E- and A-dependent protein kinases (5). It interacts directly with cyclins E and A (6), with CDK2, and with the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 (7) and also plays an indirect role in DNA replication by modulating the expression of genes, including cyclin D, that influence cell proliferation (8). Normally, Ciz1 is attached to the salt- and nuclease-resistant protein component of the nucleus referred to as the “nuclear matrix” and resides within foci that partially colocalize with sites of DNA replication (9), implicating Ciz1 in the spatial organization of DNA replication. Here we describe a Ciz1 variant that lacks part of a C-terminal domain involved in nuclear matrix attachment (Fig. 1A). Expression of this stable variant is apparently restricted to tumor cells, making clinical exploitation as a cancer biomarker highly tractable.

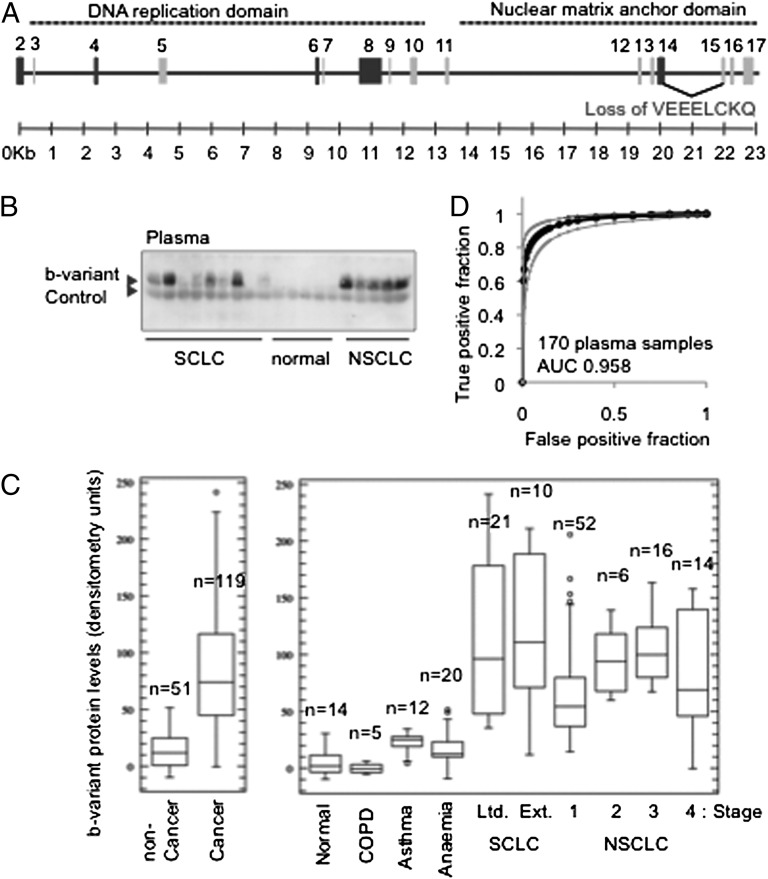

Fig. 1.

Variant Ciz1 protein in 170 samples in plasma set 1. (A) Ciz1 gene showing translated exons (numbered) and the alternative-splicing event at the exon 14/15 junction which gives rise to b-variant Ciz1. Exons that encode DNA replication domain (5) and nuclear matrix anchor domain (9) are indicated by dotted lines above. Exons that are commonly excluded from known Ciz1 variants (23) are shaded in dark gray. A complete representation of Ciz1 alternative splice variants was assembled previously (24), and transcript diversity was discussed recently (25, 26). (B) Western blot showing b-variant protein detected with antibody 2B in 1 μL of plasma from patients with SCLC or NSCLC plus five samples from individuals with no diagnosed disease. Endogenous Ig is used to normalize for loading (control). (C) Box-and-whisker plots showing the median, upper, and lower quartile, range, and outliers for data derived from Western blots by densitometry. Results for a total of 119 pretreatment lung cancer patients (Left) with the indicated type and stage of disease (Right), plus 51 samples from individuals with no disease or from patients with COPD, asthma, or anemia are shown. Individual sample values are given in Dataset S1. Using a threshold set at the mean of the noncancer samples, the test correctly classified 98% of all 119 lung cancer patients, with specificity of 85%. (D) ROC curve, with 95% confidence interval, generated for all 170 samples (AUC is 0.958). Student’s two-tailed t test with unequal variance returned a P value of <0.0001 for the noncancer samples compared with all sample sets from individuals with lung cancer.

Results

As part of a gene-focused analysis of function, we cloned human Ciz1 from a SCLC cell line and recovered multiple variants, including a prevalent transcript in which 24 nucleotides from the 3′ end of exon 14 (2475_2498del) is excluded, leading to in-frame deletion of eight amino acids (VEEELCKQ). Analysis of the sequence surrounding exons 14 and 15 revealed a second splice donor site within exon 14 (2475/6) that could support alternative splicing. Location identifiers refer to Ciz1 reference sequence NM_012127.2. We refer to the whole of predicted exon 14 as “14a,” the shorter alternative as “14b,” and Ciz1 transcripts harboring 14b as “b-variant.” Transcript frequencies among ESTs that map to the Ciz1 Unigene cluster Hs. 212395 suggested that b-variant is prevalent in neuroendocrine lung tumors, and this prevalence was confirmed by analysis of SCLC cell lines using independent detection methods (Fig. S1 and below).

As a nuclear matrix protein characterized by resistance to harsh extraction conditions, b-variant could offer a robust biomarker with potential to remain stable and detectable in body fluids. Consistent with this idea, an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody directed against the unique peptide encoded at the junction of exon 14b/exon15 (Fig. S2) detected b-variant protein by Western blot in 1 μL of plasma from patients with SCLC and NSCLC but not from healthy individuals (Fig. 1B). A diffuse but specific band of 50–60 kDa (Fig. S2) is reproducibly seen and remained stable even after extended periods of storage at 4 °C. Quantification of b-variant protein in 119 SCLC and NSCLC samples (summary information in Table 1 with sample-specific information in Dataset S1) gave a mean signal intensity of 95.8 densitometry units with an SD of 51.8, indicating considerable heterogeneity among patients. In contrast, the mean signal intensity for 51 individuals without diagnosed malignancy (who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, anemia, or no disease) was just 14.1 (SD 15.2). Unexpectedly, limited- and extensive-stage SCLC and stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 NSCLC were all significantly different from the control groups when analyzed separately (Fig. 1C), with a trend toward expression increasing with stage for stages 1, 2, and 3 NSCLC. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for all 170 samples returned an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.958 (Fig. 1D), demonstrating considerable discriminatory power in this context. To our knowledge, and despite considerable effort and progress with circulating biomarkers for other cancers (10, 11), no other single biomarker is capable of achieving this level of discrimination between patients with early-stage lung cancer and those without lung cancer. However, for maximum clinical utility a blood test must be able to identify individuals with early-stage lung cancer within populations that are at high risk of developing the disease.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of patients in plasma sets 1 and 2

| Diagnosis/classification | No. of patients | Median age | Sex (%F) | Median pack years* | Mean b-variant (±SD) |

| Set 1 | 170 | ||||

| Stage 1 NSCLC | 52 | 62 | 40 | N/d | 65.7 ± 40.0 |

| Stage 2 NSCLC | 6 | 66.5 | 50 | N/d | 94.8 ± 29.8 |

| Stage 3 NSCLC | 16 | 66 | 38 | N/d | 103.6 ±− 26.3 |

| Stage 4 NSCLC | 14 | 69 | 43 | N/d | 85.0 ± 52.1 |

| Limited stage SCLC | 21 | 67 | 48 | N/d | 112.0 ± 67.1 |

| Extensive stage SCLC | 10 | 64 | 70 | N/d | 118.0 ± 70.1 |

| All cancer | 119 | 65 | 44 | N/d | 95.8 ± 51.8 |

| COPD | 5 | 59 | 20 | N/d | −0.3 ± 4.3 |

| Asthma | 12 | 42.5 | 58 | N/d | 17.6 ± 16.9 |

| Anemia | 20 | 47.5 | 80 | N/d | 23.7 ± 8.0 |

| No diagnosed disease | 14 | 36 | 29 | N/d | 5.9 ± 12.3 |

| All noncancer | 51 | 46 | 55 | N/d | 14.1 ±15.2 |

| Set 2 | 160 | ||||

| Stage 1 squamous cell carcinoma | 20 | 67 | 20 | 45 | 64.3 ± 32.0 |

| Stage 1 adenocarcinoma | 20 | 71.5 | 60 | 41 | 35.2 ± 14.4 |

| Benign lung nodules | 20 | 60 | 85 | 20 | 8.6 ± 22.0 |

| Inflammatory lung disease | 20 | 67.5 | 60 | 30 | 6.3 ± 0.4 |

| Smokers | 80 | 64.5 | 55 | 34 | 6.35 ± 12.2 |

N/d, no data.

*One pack year is defined as 20 cigarettes smoked every day for a year.

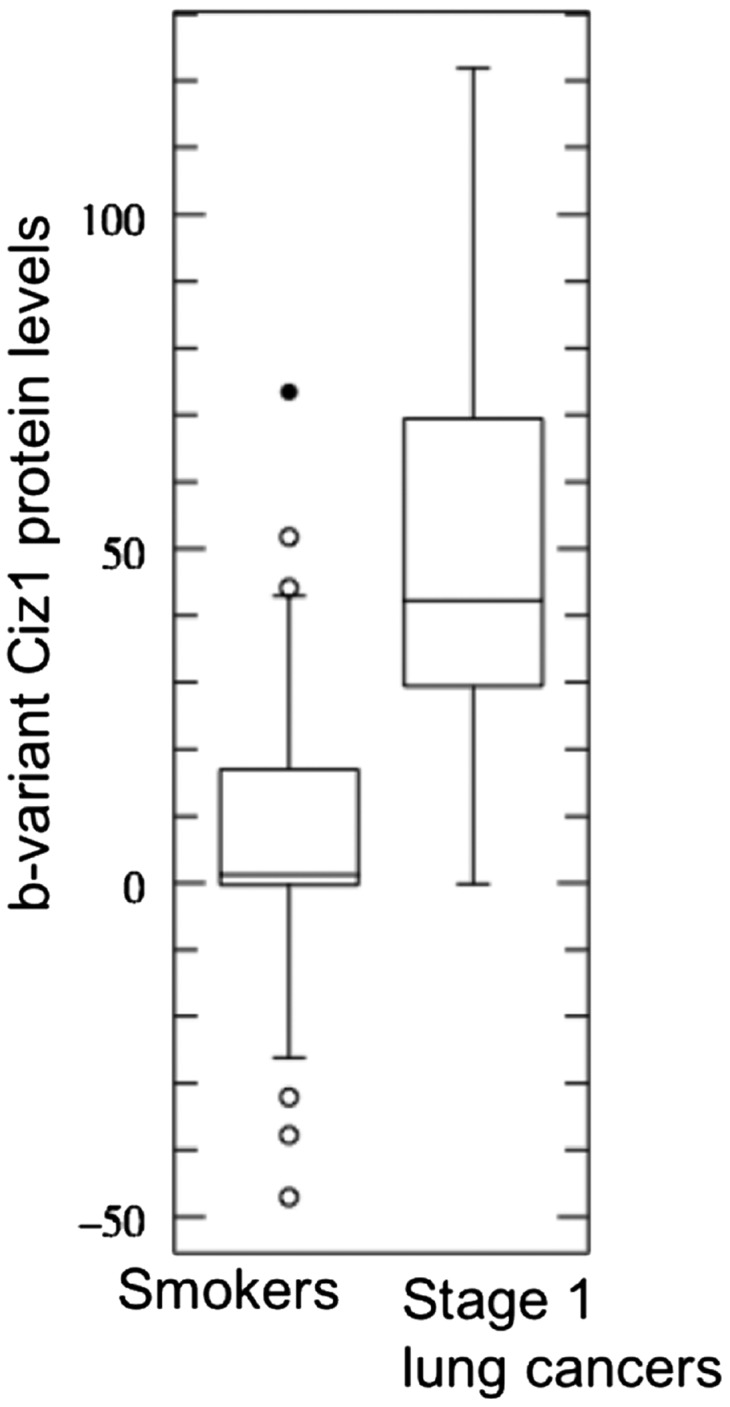

An important potential application is as a test for lung cancer in individuals with lung nodules identified by CT. A test that can positively identify those individuals with lung cancer could help reduce the frequency of surgical intervention and favorably affect both cost and outcome. To look specifically at the discriminatory power of b-variant Ciz1 in comparison with (i) age-matched smokers with ≥10 y of cigarette smoking history but without diagnosed cancer and (ii) individuals with nonmalignant lung nodules or inflammatory lung disease, we analyzed a second, independent, archived set of case and control plasma samples (set 2, summary information in Table 1 with sample-specific information in Dataset S2), using high-throughput Western blots and just 0.5 μL of each sample. Comparison of the smokers (median age 64.5 y) with 20 individuals with stage 1 squamous cell carcinoma (median age 67 y) and 20 patients with stage 1 adenocarcinoma (median age 71.5 y) revealed clear discriminatory power in both contexts and ROC AUC values in excess of 0.9 (Fig. 2). Western blot images for all samples are shown in Fig. S3, and raw and normalized results are given in Dataset S2. These data show that b-variant Ciz1 has significant potential for detecting limited-stage lung cancer among at-risk groups.

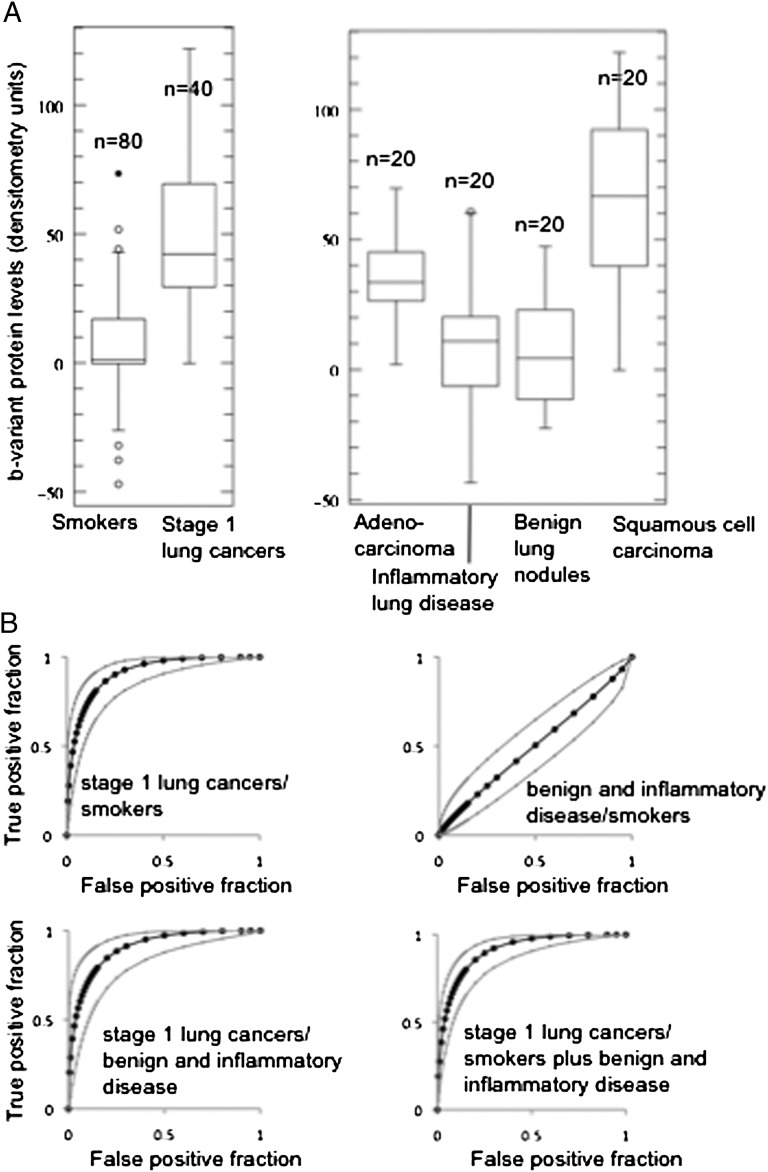

Fig. 2.

Variant Ciz1 protein in 160 samples in plasma set 2. (A) Box plot showing results for 80 smokers with more than 10 y of smoking history and for 40 patients with stage 1 NSCLC with similar smoking history (Left) and for 20 individuals diagnosed with stage 1 adenocarcinoma, inflammatory lung disease (granuloma), benign lung nodules (carcinoid, hamartoma), or stage 1 squamous cell carcinoma (Right), showing lower, median, and upper quartiles and outliers (circles). (B) ROC curve with 95% confidence intervals for the indicated comparisons. AUCs are 0.913 when samples from 80 smokers are compared with samples from 40 patients with stage1 lung cancer, 0.905 when samples from 40 patients with benign nodules or inflammatory disease are compared with samples from 40 patients with stage1 lung cancer, and 0.909 when all samples from smokers and patients with benign nodules or inflammatory disease are compared with all samples from patients with stage1 lung cancer, but are only 0.503 when samples from smokers are compared with samples from patients with benign nodules or inflammatory disease. Western blots showing b-variant protein in the 0.5 μL of plasma used for each of the 160 samples are shown in Fig. S3; individual b-variant levels and clinical parameters are given in Dataset S2. Student’s two-tailed t test with unequal variance returned a P value of <0.0001 for the samples from patients with cancer compared with samples either from smokers or from patients with benign nodules or inflammatory disease.

The overall performance with set 1 and set 2 is shown in Table 2. Encouragingly, using a threshold set at the mean of 40 individuals with benign lung nodules or inflammatory diseases of the lung (set 2), b-variant Ciz1 correctly classified 95% of patients with stage 1 lung cancer, with an overall specificity of 71% (set 2). Moreover, when the threshold is set at the mean of all of the noncancers in the discovery set (set 1), 95% of the patients with stage 1 lung cancer in the validation set (set 2) are correctly classified, with an overall specificity of 75%. Under both circumstances the false-positive rate was ∼50%, suggesting that, if it were applied as a secondary screen to high-risk groups with suspicious CT results (4), b-variant Ciz1 could halve the number of individuals referred for costly and invasive follow-up procedures. In the context of high-risk smokers without CT-based diagnosis, the biomarker also would appear to have utility, with 95% of patients with stage 1 lung cancer (in set 2) falling above the mean of the smokers and only 34% of smokers being placed in the suspicious category. Thus, positioning the test either before or after CT could offer significant advantages over the use of CT alone.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity estimates for sample sets 1 and 2

| Thresholds used | False negatives | Sensitivity (%) | False positives | False positive (%) | Total in wrong group | Specificity (%) | |

| Set 1 | |||||||

| Mean of all noncancers in set 1 | 14.07 | 3/119 (all cancer) | 98 | 23/51 | 45 | 26/170 | 85 |

| Mean of all noncancers in set 1 | 14.07 | 0/52 (stage 1 NSCLC) | 100 | 23/51 | 45 | 23/103 | 78 |

| Set 2 | |||||||

| Mean of all noncancers in set 2 | 6.27 | 2/40 | 95 | 48/120 | 40 | 50/160 | 69 |

| Mean of all smokers in set 2 | 6.35 | 2/40 | 95 | 27/80 | 34 | 29/120 | 76 |

| Mean of benign and inflammatory in set 2 | 7.45 | 2/40 | 95 | 21/40 | 53 | 23/80 | 71 |

| Mean of all noncancers in set 1 | 14.07 | 2/40 (stage 1) | 95 | 40/120 (all non cancer) | 33 | 42/160 | 74 |

| Mean of all noncancers in set 1 | 14.07 | 2/40 (stage 1) | 95 | 23/80 (smokers) | 29 | 25/120 | 79 |

| Mean of all noncancers in set 1 | 14.07 | 2/40 (stage 1) | 95 | 18/40 (benign and inflammatory) | 45 | 20/80 | 75 |

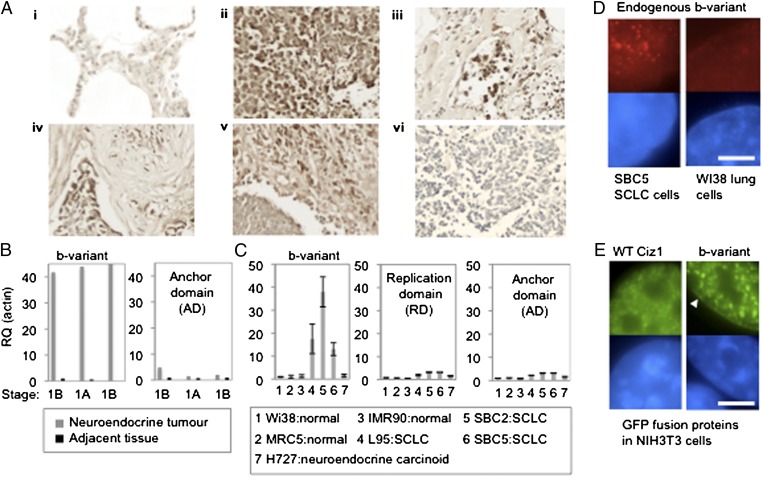

Consistent with the presence of b-variant Ciz1 in patient plasma, immunohistochemical analysis of primary tumors from patients with neuroendocrine lung cancer revealed b-variant–positive cells in 34 of 35 patients (Fig. 3A). Staining was heterogeneous in both distribution and level, with positive cells evident throughout the tumor in some individuals and limited to isolated cells in others. These results confirm that b-variant Ciz1 is a tumor antigen with the potential for exploitation as a lung cancer biomarker. Complementary transcript analysis reported at least 40-fold elevation in bulk tumor RNA from neuroendocrine tumors compared with matched adjacent tissue for all three patients tested (Fig. 3B). In addition, b-variant transcript was elevated in 13 SCLC cell lines compared with control lines (Fig. 3C and Fig. S1E), confirming that expression is common in lung cancer cells. Notably, for both the cell lines and the primary tumors, Ciz1 also is elevated (Fig. 3 B and C), but to a lesser extent.

Fig. 3.

Expression of Ciz1 b-variant in tumors and cell lines. (A) Sections from SCLC tissue array ARY-HH0117, probed with b-variant antibody 2B (dark brown), showing (i) normal lung negative for b-variant; (ii and iii) b-variant in representative SCLC; (iv) SCLC with positive tumor cells and stromal cells; (v) SCLC with positive stromal cells ; (vi) SCLC negative for b-variant. B-variant was recorded in 29/35 tumors and in stromal cells in 5/35 tumors. Only one pair of tumor sections did not contain b-variant–positive cells. (B) Relative quantification (RQ) of b-variant transcript (primers P1/P2, probe T2) and Ciz1 AD transcript in SCLC tumors of the indicated disease stages plus adjacent tissue from three patients. Results are normalized to actin and calibrated to the first adjacent sample. (C) Ciz1 b-variant AD (primers 6/7, probe 16) and replication domain (13/14, probe 7) in lung-derived cell lines, showing average of three technical replicates after normalization to actin and calibration to WI38 cells, with SEM. Sequences are given in Table S3. All three SCLC lines, plus 10 others (Fig. S1), have elevated b-variant. (D) Detergent-resistant b-variant protein (red) in nuclei of SCLC cells, but not normal lung cells, was detected with antibody 2B. DNA is blue. (Scale bar, 5 microns.) (E) GFP-hCiz1 WT (full length with exon 14a) and GFP-hCiz1 b-variant (with exon 14b). Both proteins form nuclear foci, but foci are larger for the b-variant and are accompanied by localization around the periphery (white arrowhead).

Visualization by immunofluorescence revealed that the b-variant protein resides as subnuclear foci that are somewhat larger than WT Ciz1 in the nucleus in SCLC cell line SBC5 but not in the normal lung cell line Wi38 (Fig. 3D) (9). When transfected into NIH 3T3 cells, GFP-tagged Ciz1 constructs with exon 14a or 14b produced protein that was exclusively nuclear and punctate and which resisted extraction (Fig. 3E). Thus, we saw no gross differences in subcellular localization or attachment to nonchromatin nuclear structures. However subtle differences in subnuclear distribution were evident, with the b-variant forming larger aggregates and localizing to the perimeter of the nucleus as well as to foci. Therefore, the loss of eight amino acids from the anchor domain (AD) of Ciz1 does subtly affect the spatial organization of Ciz1, leading us to suggest that it may influence the functional compartment into which the DNA replication activity of Ciz1 is targeted and possibly, therefore, the execution of replication-coupled events. Notably, normal cells do not tolerate sustained overexpression of ectopic Ciz1 or b-variant Ciz1 [despite an early positive effect on initiation of DNA replication (5), shown previously for WT Ciz1], because this overexpression ultimately results in the loss of nuclear integrity in NIH 3T3 cells and loss of adherence within 33 h of transfection via a mechanism that is not apoptosis (Fig. S4).

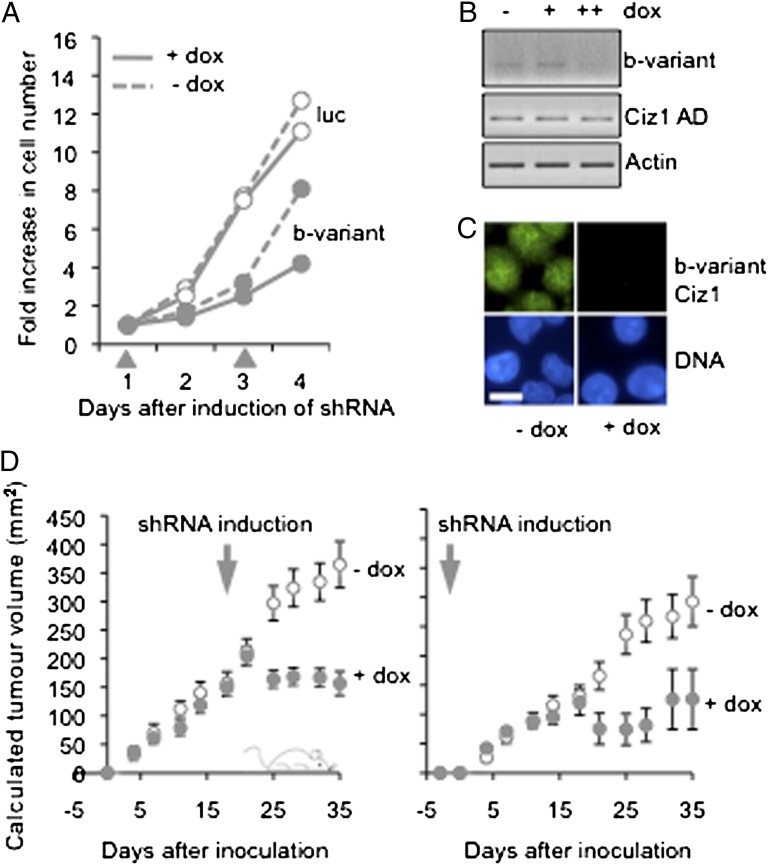

The increasingly well-characterized role of Ciz1 in DNA replication makes it a candidate therapeutic target with the potential to modulate cell proliferation. Inhibition of Ciz1 expression using siRNA restrains cell proliferation in murine NIH 3T3 cells (5) and human SBC5 cells (Fig. S5). Therefore, if tumor cells that express the b-variant rely on it to support S phase, its inhibition could selectively restrain their proliferation. From a panel of junction-spanning siRNAs that suppress the expression of the b-variant transcript and protein but not Ciz1 isoforms that contain exon 14a (Fig. S6 and Table S1), we selected the most potent sequence (Fig. S5A) and tested its effect on the proliferation of SBC5 SCLC cells (which express endogenous b-variant; Fig. 3 C and D) and also H727 cells (which do not express endogenous b-variant; Fig. 3C and Fig. S5B) when delivered from an inducible shRNA vector. Like RNAi targeted against a constant region of Ciz1, b-variant shRNA effectively restrained cell proliferation in culture (Fig. 4A). As expected, b-variant transcript, but not other forms of Ciz1, was suppressed selectively (Fig. 4B), and this suppression had a significant impact on b-variant protein (Fig. 4C). Importantly, in a xenograft model of human SCLC in which s.c. tumors were derived from SBC5 cells (12), b-variant shRNA dramatically restrained tumor growth. Similar results were obtained when expression was induced at the time of tumor cell inoculation or after tumors had formed (Fig. 4D). Together, these in vitro and in vivo experiments show that the unique junction generated by alternative splicing of Ciz1 exon 14 can be exploited to suppress variant expression specifically and that this suppression is sufficient to inhibit tumor cells that express it, identifying b-variant Ciz1 as a functionally relevant driver of tumor cell proliferation.

Fig. 4.

Suppression of the expression of the Ciz1 b-variant restrains proliferation of lung cancer cells. (A) Effect of luciferase control shRNA (luc) and b-variant junction-selective RNAi sequence 4 on SBC5 cells, expressed as fold increase in cell number over 4 d after induction of shRNA with doxycycline at days 1 and 3 (gray arrowheads). RNAi sequences are described in Fig. S6. (B) RT-PCR analysis of Ciz1 AD (primers P1/P2), b-variant (P4/P3), and actin (P11/P12) in SBC5 b-variant shRNA 4 cells, without (− dox) and with induction of expression at 26 h (+) or as two doses (++) administered at 26 h and 1 h before isolation. (C) Detergent-resistant endogenous b-variant protein (antibody 2B, green) in the nucleus of SBC5 b-variant shRNA 4 cells 2 d after induction of shRNA. DNA is blue. (Scale bar, 10 microns.) (D) Xenograft tumor formation in mice. Control mice were inoculated with SBC5 b-variant shRNA 4 cells and maintained in the absence of doxycycline (open circles, group 1). Additional cohorts (filled circles) were given doxycycline continuously from 3 d before inoculation (group 3, Right) or after 21 d (group 2, Left). For the comparison of groups 1 and 2, mice with tumors less than 100 mg at 21 d were discounted, creating cohorts with low variation. Graphs show mean tumor weight from 10–15 animals, with SEM. (Data are given in Dataset S3.)

Discussion

The evidence presented here shows that a cancer-associated variant isoform of the nuclear matrix protein Ciz1 holds considerable promise as the basis of a blood test for early-stage lung cancer. As biomarkers, nuclear matrix proteins offer several advantages. They are at the heart of a dysregulated nucleus and are likely to play causative roles in epigenetic control of gene expression. Perhaps more importantly, nuclear matrix proteins are inherently stable, offering practical advantages that make exploitation feasible. As a group they are biochemically defined as the fraction that remains after extraction to remove lipids, soluble proteins, cytoskeleton, chromatin, and associated proteins, which when observed microscopically forms a proteinaceous network (13) made up of constitutive and cell-type–specific components (14). Increasingly nuclear matrix proteins such as NMP22, BCLA4, PC1, and NM179 are gaining credibility as tumor markers for bladder (15), cervix (16), and prostate cancer (17), respectively. However, despite their promise, the need remains for markers with tumor-specific profiles that can be used to complement examination of the structure of nuclei. B-variant Ciz1 is one such molecule, robustly quantifiable in the blood of patients who have lung cancer, that is both a driver of DNA replication and tumor cell proliferation and a stable derivative of circulating tumor cells. Notably, this biomarker was identified through intensive gene-focused analysis of expression and function rather than by mutation- or gene-expression–profiling approaches.

Analysis by high-throughput Western blot offers a direct, visual output clarified by sample denaturation that eliminates epitope masking in native samples. Furthermore, fractionation on the basis of molecular weight effectively isolates signal from that of potentially reactive contaminants, giving a clear picture of the potential of the biomarker. Western blot analysis, however, may not report the full dynamic range of biomarker concentrations and is not easily applied outside a research laboratory. Therefore, routine application of a b-variant–based test in a clinical context will require the development of a more streamlined method, such as ELISA, with a simplified quantitative output. Thus, we acknowledge that, although the data presented show that the biomarker holds considerable discriminatory power, the assay ultimately will need to switch platforms and be validated further in that context.

Alteration in the structure of nuclei, detected by light microscopy of tumor biopsies, has remained the most reliable method of cancer diagnosis for more than 100 y (18), but the underlying abnormalities have been difficult to define at the molecular level. Detailed and focused analysis of the relationship between nuclear architecture and essential nuclear events is beginning to identify new players involved in establishing order (19). Moreover, disease-associated molecular changes in these players are now becoming apparent, offering exciting opportunities for the development of new clinically relevant tools.

Materials and Methods

Additional methods are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Cells.

NIH 3T3 cells were grown as described (20). SBC5 cells, obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (JCRB) were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Sigma), 1% penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine (Gibco), and 10% (vol/vol) FBS (Biosera). RNAi with siRNA and inducible shRNA is described in SI Materials and Methods. All other cells were from the European Collection of Cell Cultures or JCRB and were cultured as recommended.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

RNA from cell lines (Table S2) was isolated with TRIzol, and cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). RNA from tumors and adjacent tissue (Cytomyx) was reverse transcribed using M-MLV (Promega) and random primers (Promega) plus oligo-dT primer 12–18 (Invitrogen). Primers (Table S3) P6/P7 or P1/P2 (Sigma Aldrich) were coupled with junction probe T2 (MWG) for b-variant Ciz1 and were verified using plasmid templates (Fig. S1). Relative expression was calculated using the comparative cycle threshold (Ct) method (2−ΔΔCt), and results were expressed relative to normal cells or tissue.

Antibodies.

B-variant–specific rabbit polyclonal antibodies (2B) were generated by Covalab using the splice-junction sequence (C-DEEEIEVRSRDIS) (Fig. S2A). Sera first were subtracted for antibodies reactive against flanking sequences in a negative control peptide that includes the amino acids absent from b-variant (DEDEEEIEVEEELCKQVRSRDISR) and then were adsorbed to peptide containing the b-variant junction to generate affinity-purified antibody 2B. Purified antibodies were characterized in a range of assays including immunofluorescence and Western blot on cells expressing WT or b-variant forms of human GFP-Ciz1 (Fig. S2 B and C) and lung cancer cells expressing endogenous b-variant Ciz1 with and without specific suppression by b-variant shRNA (Figs. 3D and 4C).

Immunodetection and Analysis.

For immunofluorescence, the b-variant was detected after paraformaldehyde fixation using affinity-purified polyclonal antibody 2B (Fig. S2) and then anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Folio Bioscience). Subcellular fractionation was carried out as described (21). For immunohistochemistry, 2B was applied to SCLC tissue microarray ARY-HH0117 (Folio Biosciences) and visualized using Ultraview Universal DAB (Ventana) with hematoxylin counterstain. Duplicate cores representing 35 SCLC (grade 4) and tissue from five normal or cancer-adjacent lungs were analyzed by a certified pathologist at Phylogeny, Inc. Cores were classified as PP (containing mostly b-variant–positive cancer cells), P (containing b-variant–positive cancer cells with variable intensity and number, exceeding 10% of cells), PS (containing positive stromal cells), PPS (containing strongly positive stromal cells), or N (containing no positive cells). Images shown in Fig. 3A are derived from (i) core H8, (ii) G7. (iii) D10, (iv) G6, and (v) F8.

Plasma Analysis.

For sample set 1, 1 μL of plasma was resolved by 8% SDS/PAGE through 12 cm × 12 cm maxi-gels (Atto) and was transferred to nitrocellulose by semidry blotting. For samples in set 2, 0.5 μL of plasma was denatured using Epage buffer, resolved by electrophoresis through precast E-PAGE 8% 48-well gels, and was transferred to nitrocellulose using iBlot dry blotting system (all Invitrogen). A more detailed description is given in SI Materials and Methods. Membranes were probed with anti-Ciz1 b-variant–specific affinity purified polyclonal antibody 2B, diluted 1/500 in PBS, 10% (wt/vol) milk powder, and 0.1% Tween 20. Antibody 2B was detected with peroxidase-IgG light chain-specific, highly cross-adsorbed monoclonal anti-rabbit antibody (211-032-171; Jackson Immunological Research). Western blots were quantified using Image J (National Institutes of Health), and samples were assigned a value after normalization to loading control and calibration to a constant normal sample (given a value of 0), and to an NSCLC sample (given a value of 100).

Statistics.

Groups were compared using Student’s two-tailed t-tests in which a P value <0.05 is considered significant. Results are displayed in box-and-whisker plots showing sample minimum and maximum, lower, median, and upper quartile, and outliers, calculated using www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats/ (accessed October 21, 2011) and as ROC curves using www.rad.jhmi.edu/jeng/javarad/roc/JROCFITi.html (accessed February 7, 2011). Means and SDs were calculated using Excel 2008 for Mac (Microsoft).

Study Approval.

For sample set 1, blood samples were collected with written, informed consent, according to National Health Service-approved protocols at the Paterson Institute for Cancer Research, University of Manchester, and were processed as described previously (22). Additional plasma samples listed in Dataset S1 were obtained from biobanks and were collected according to Institutional Review Board-approved protocols. All cases and control samples in set 2 were collected according to National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network standard operating procedures. Samples from patients diagnosed with lung cancer or other nonmalignant lung disorders were collected at the Thoracic Oncology Laboratories of the New York University Langone Medical Center (New York) at the time of thoracic surgery, and all diagnoses were confirmed histologically (as adenocarcinoma, inflammatory lung disease, benign lung nodules, or squamous cell carcinoma) after excision of the abnormal lesion. For the smoker cohort, samples were collected from age-matched smokers at the Division of Pulmonary, and Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, New York University School of Medicine. Study-specific approval was granted by the Department of Biology, University of York, Research Ethics Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rose Wilson, Jian Mei Hou, Faisal Abdel Rahman, and Mark Thornquist; Ellen Eylers, Ting-An Yie, and Nihir Patel (New York University School of Medicine) for sample collection and Alissa Greenberg, MD, for clinical follow-up; Lynsey Priest for sample collection at The Christie National Health Service Foundation Trust; Said El Alaou (Covalab) for generation of variant-specific antibodies; and Yulia Maxuitenko (Southern Research Institute) for in vivo RNAi analysis. Sample collection at The Christie National Health Service Foundation Trust was supported by CHEMORES Sixth Framework Programme Contract LSHC-CT-2007-037665 (to F.H.B), and at New York University School of Medicine by National Cancer Institute Early Detection Research Network Grant U01CA086137 (to W.N.R. and H.I.P.) This work was funded by Cizzle Biotech, the University of York proof-of-concept fund, and Yorkshire Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The findings reported in this paper arise directly out of basic research at the University of York (York, Yorkshire, United Kingdom) on the Ciz1 protein and its role in the spatial and temporal organization of DNA replication. The findings are the result of an academic and commercial collaboration, funded in part by Cizzle Biotech, which is a spin-out company of the University of York. G.H. and D.C. are partially funded by Cizzle Biotech. D.C. and J.F.X.A hold shares in Cizzle Biotech.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Author Summary on page 18263 (volume 109, number 45).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1210107109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brambilla E, Travis WD, Colby TV, Corrin B, Shimosato Y. The new World Health Organization classification of lung tumours. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(6):1059–1068. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00275301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones MH, et al. Two prognostically significant subtypes of high-grade lung neuroendocrine tumours independent of small-cell and large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas identified by gene expression profiles. Lancet. 2004;363(9411):775–781. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin DR. Imaging in lung cancer: Recent advances in PET-CT and screening. Thorax. 2011;66(4):275–277. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.149153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aberle DR, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coverley D, Marr J, Ainscough JF-X. Ciz1 promotes mammalian DNA replication. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 1):101–112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copeland NA, Sercombe HE, Ainscough JF, Coverley D. Ciz1 cooperates with cyclin-A-CDK2 to activate mammalian DNA replication in vitro. J Cell Sci. 2010;123(Pt 7):1108–1115. doi: 10.1242/jcs.059345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitsui K, Matsumoto A, Ohtsuka S, Ohtsubo M, Yoshimura A. Cloning and characterization of a novel p21(Cip1/Waf1)-interacting zinc finger protein, ciz1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264(2):457–464. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.den Hollander P, Rayala SK, Coverley D, Kumar R. Ciz1, a Novel DNA-binding coactivator of the estrogen receptor α, confers hypersensitivity to estrogen action. Cancer Res. 2006;66(22):11021–11029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ainscough JF, et al. C-terminal domains deliver the DNA replication factor Ciz1 to the nuclear matrix. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 1):115–124. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehmann M, et al. Identification of potential markers for the detection of pancreatic cancer through comparative serum protein expression profiling. Pancreas. 2007;34(2):205–214. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000250128.57026.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leman ES, et al. Evaluation of colon cancer-specific antigen 2 as a potential serum marker for colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1349–1354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Miki T, Yano S, Hanibuchi M, Sone S. Bone metastasis model with multiorgan dissemination of human small-cell lung cancer (SBC-5) cells in natural killer cell-depleted SCID mice. Oncol Res. 2000;12(5):209–217. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wan KM, Nickerson JA, Krockmalnic G, Penman S. The nuclear matrix prepared by amine modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(3):933–938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albrethsen J, Knol JC, Jimenez CR. Unravelling the nuclear matrix proteome. J Proteomics. 2009;72(1):71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Le TS, Myers J, Konety BR, Barder T, Getzenberg RH. Functional characterization of the bladder cancer marker, BLCA-4. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(4):1384–1391. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0455-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keesee SK, et al. Preclinical feasibility study of NMP179, a nuclear matrix protein marker for cervical dysplasia. Acta Cytol. 1999;43(6):1015–1022. doi: 10.1159/000331347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Subong EN, et al. Monoclonal antibody to prostate cancer nuclear matrix protein (PRO:4-216) recognizes nucleophosmin/B23. Prostate. 1999;39(4):298–304. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990601)39:4<298::aid-pros11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zink D, Fischer AH, Nickerson JA. Nuclear structure in cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(9):677–687. doi: 10.1038/nrc1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajapakse I, Groudine M. On emerging nuclear order. J Cell Biol. 2011;192(5):711–721. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coverley D, Laman H, Laskey RA. Distinct roles for cyclins E and A during DNA replication complex assembly and activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(7):523–528. doi: 10.1038/ncb813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munkley J, et al. Cyclin E is recruited to the nuclear matrix during differentiation, but is not recruited in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(7):2671–2677. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou JM, et al. Evaluation of circulating tumor cells and serological cell death biomarkers in small cell lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(2):808–816. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman FA, Ainscough JF-X, Copeland N, Coverley D. Cancer-associated missplicing of exon 4 influences the subnuclear distribution of the DNA replication factor CIZ1. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(10):993–1004. doi: 10.1002/humu.20550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahman FA, Aziz N, Coverley D. Differential detection of alternatively spliced variants of Ciz1 in normal and cancer cells using a custom exon-junction microarray. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao J, et al. Mutations in CIZ1 cause adult onset primary cervical dystonia. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(4):458–469. doi: 10.1002/ana.23547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greaves EA, Copeland NA, Coverley D, Ainscough JF. Cancer-associated variant expression and interaction of CIZ1 with cyclin A1 in differentiating male germ cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125(Pt 10):2466–2477. doi: 10.1242/jcs.101097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]