Abstract

Objectives

To describe predictors of pregnancy and changes in pregnancy incidence among HIV-positive women accessing HIV clinical care.

Methods

Data were obtained through the linkage of two separate studies; the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort study (UK CHIC), a cohort of adults attending 13 large HIV clinics, and the National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood (NSHPC), a national surveillance study of HIV-positive pregnant women. Pregnancy incidence was measured using the proportion of women in UK CHIC with a pregnancy reported to NSHPC. Generalised estimating equations were used to identify predictors of pregnancy and assess changes in pregnancy incidence in 2000-2009.

Results

The number of women accessing care at UK CHIC sites increased as did the number of pregnancies (from 72 to 230). Older women were less likely to have a pregnancy (adjusted Relative Rate (aRR) 0.44 per 10 year increment in age [95% CI [0.41-0.46], p<0.001) as were women with CD4<200 cells/mm3 compared with CD4 200-350 cells/mm3 (aRR 0.65 [0.55-0.77] p<0.001) and women of white ethnicity compared with women of black-African ethnicity (aRR 0.67 [0.57-0.80], p<0.001). The likelihood that women had a pregnancy increased over the study period (aRR 1.05 [1.03-1.07], p<0.001). The rate of change did not significantly differ according to age group, ART use, CD4 group or ethnicity.

Conclusions

The pregnancy rate among women accessing HIV clinical care increased in 2000-2009. HIV-positive women with, or planning, a pregnancy require a high level of care and this is likely to continue and increase as more women of older age have pregnancies.

Keywords: HIV, pregnancy, pregnancy rate, maternal age, highly active antiretroviral therapy, maternal-fetal infection transmission, United Kingdom

Introduction

Diagnosed HIV-positive women accessing HIV-clinical care in the UK include women of different ethnicities, ages and levels of morbidity. The characteristics of this diverse group continue to change with an increasing proportion of older women and women on antiretroviral therapy (ART) [1, 2]. With advances in ART and developments in prescribing practice [3-5] leading to the improved wellbeing and longevity of HIV-positive women [6, 7], coupled with effective prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) [8], many HIV-positive women choose to have children [9, 10] and an increasing number have repeat pregnancies [11, 12].

Changes in the characteristics and clinical features of pregnant HIV-positive women are likely to reflect changes among women accessing HIV-clinical care, as well as changes in the pregnancy rate among specific groups. However, when using only data from antenatal studies of HIV-positive women it is not possible to assess the extent to which pregnancy incidence has changed over time among women accessing care. [1] Using data from two studies linked at the person level, an HIV cohort study of adults accessing HIV care and a national surveillance study of HIV-positive women accessing antenatal care, our aim was to identify factors predictive of having a pregnancy among women accessing HIV care at 13 large clinics in the UK and to describe trends in the pregnancy rate in 2000-2009.

Methods

Creating a combined dataset

Data were obtained from two studies, the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) study and the National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood (NSHPC). The UK CHIC study collates extensive data on HIV-related clinical care on an annual basis from (currently) 13 large HIV clinics in the UK, but does not record pregnancy-related data [13]. It represents approximately 30% of women aged 16-49 years who accessed care in the UK in 2000-2009. The NSHPC collates pregnancy data on HIV-positive women accessing antenatal care from all maternity units in the UK and Ireland using active surveillance. The records of women found in both these pseudonymised datasets were merged to create a dataset containing routine clinical and antenatal data for women with a pregnancy in 1996-2009 and who were HIV-diagnosed before or during pregnancy (n=2054). The methodology used to find women in both datasets has been described in more detail elsewhere [13-15] and further information on each study is available from www.nshpc.ucl.ac.uk and www.ukchic.org.uk. In brief, as neither study, records of women in UK CHIC were first linked to records in NSHPC using date of birth (DOB) to create a temporary dataset containing all pairs of records with identical DOB. These pairs were then assessed using fields including CD4 count, HIV-diagnosis date and site of care, to identify pairs that were likely to be genuine matches, i.e. records relating to the same woman. A dataset was created containing records for all women who accessed care at UK CHIC sites in 2000-2009 incorporating antenatal data for those with a pregnancy. Women were defined as ‘accessing care’ in a given calendar year if they had either a CD4, viral load or hepatitis assessment, AIDS diagnosis, or any ART or hepatitis drug start or stop dates recorded. data for years when women accessed care and were of childbearing age (16-49 years). - this meant that some years in which women had a pregnancy were excluded as the woman had not accessed care at a UK CHIC site.

Variables and definitions

Index pregnancy refers to the first pregnancy after HIV-diagnosis in the UK or the pregnancy during which HIV-diagnosis occurred. Repeat pregnancy refers to any subsequent pregnancy (even if it was the first pregnancy during the study period). As pregnancies could overlap two calendar years, year of pregnancy refers throughout to the year of conception. Estimated date of conception was calculated as 266 days before the expected date-of-delivery (normally estimated using ultrasound), as this allowed date of conception to be calculated for all pregnancies including those ending early.

Variables in the dataset included ethnicity, probable route of infection, age and ART status at start of year, earliest CD4 count in the year (determined using UK CHIC data) and whether they became pregnant. For women with a pregnancy, data were also included on the estimated date of conception, pregnancy outcome and whether the pregnancy was an index or repeat pregnancy.

Pregnancies resulting in a live or stillbirth were categorised as ending at delivery and pregnancies resulting in miscarriage or termination, and ectopic pregnancies, were categorised as ending early. Where pregnancy outcome was not known (n=23), the pregnancy was excluded from the analysis of factors predictive of pregnancy outcome.

Statistical methods

Analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). The characteristics of women under follow-up and with a pregnancy in each year were first described. Trends seen in the characteristics of pregnant women are likely to reflect changes in the characteristics of women accessing care, and do not necessarily reflect the impact of any particular characteristic on the rate of pregnancy itself. Thus, the pregnancy rate was described for each calendar year using the number of women (aged 16-49 years) with clinical data in UK CHIC as the denominator and the number with a pregnancy (all outcomes) starting that year as the numerator. If a woman was diagnosed with HIV during her index pregnancy and attended care for the first time during that year (463 pregnancies), the attendance and pregnancy for that year were excluded from analyses (i.e. removed from the numerator and denominator for that calendar year). However, all future years during which the woman attended care (and any subsequent pregnancies) were included. If a woman had more than one pregnancy starting in the same calendar year, only the first was considered.

Predictors of pregnancy were identified using generalized estimating equations (Poisson regression), unadjusted and adjusted for year, age, CD4, ethnicity and ART use, accounting for repeat measures. We also considered the addition of interaction terms between calendar year and each covariate in the model in order to investigate whether there was evidence that calendar year trends varied in some subgroups of the population. Factors associated with pregnancy ending in delivery versus ending early were also assessed using generalized estimating equations. Factors considered were age, HIV exposure group, ethnicity, calendar year, ART use and CD4 count.

Results

Characterising women accessing HIV care

In total, 7853 women aged 16-49 years accessed HIV care at UK CHIC sites over the period 2000-2009, the number doubling from 2074 in 2000 to 4876 in 2009. The majority of women were of black-African ethnicity and most were infected via heterosexual sex (Table 1). During the period 2000-2009, the characteristics of women accessing care changed somewhat; the proportion of women of black-African, black-Caribbean or black-other ethnicity increased and the proportion of white women decreased. The proportion that had been infected via heterosexual sex or themselves via mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) increased and the proportion infected via injecting drug use or contaminated blood/blood products decreased. The average age of women under follow-up increased with the number aged 36-49 years almost quadrupling (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of HIV-positive women of childbearing age receiving HIV clinical care at UK CHIC sites in 2000-2009.

| 2000/1 | % | 2002/3 | 2004/5 | 2006/7 | 2008/9 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 4555 | 6340 | 7901 | 9359 | 9942 | ||||||

| Median age (years) (IQR) | 33 | (29-38) | 34 | (29-39) | 35 | (30-40) | 36 | (31-41) | 37 | (32-42) | |

| Age group | 16-25 | 450 | 9.9 | 621 | 9.8 | 782 | 9.9 | 855 | 9.1 | 778 | 7.8 |

| (years) | 26-35 | 2401 | 52.7 | 3059 | 48.2 | 3426 | 43.4 | 3631 | 38.8 | 3410 | 34.3 |

| 36-49 | 1704 | 37.4 | 2660 | 42.0 | 3693 | 46.7 | 4873 | 52.1 | 5754 | 57.9 | |

| ART use | On ART | 2220 | 48.7 | 3278 | 51.7 | 4371 | 55.3 | 5863 | 62.7 | 6780 | 68.2 |

| CD4 count | ≤200 | 1140 | 25.0 | 1336 | 21.1 | 1326 | 16.8 | 1226 | 13.1 | 1045 | 10.5 |

| (cells/mm3) | 201-350 | 1146 | 25.2 | 1602 | 25.3 | 2045 | 25.9 | 2121 | 22.7 | 1927 | 19.4 |

| >350 | 1849 | 40.6 | 2979 | 47.0 | 4131 | 52.3 | 5542 | 59.2 | 6654 | 66.9 | |

| NK | 420 | 9.2 | 423 | 6.7 | 399 | 5.0 | 470 | 5.0 | 316 | 3.2 | |

| Median CD4 (cells/mm3) | (IQR) | 338 | (220-532) | 353 | (217-520) | 380 | (247-543) | 420 | (280-583) | 463 | (319-640) |

| Probable route of Injecting |

Heterosexual sex | 3606 | 79.2 | 5238 | 82.6 | 6703 | 84.8 | 7883 | 84.2 | 8297 | 83.5 |

| Injecting drug use | 355 | 7.8 | 373 | 5.9 | 367 | 4.6 | 378 | 4.0 | 332 | 3.3 | |

| Contaminate blood | 27 | 0.6 | 35 | 0.6 | 40 | 0.5 | 47 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.3 | |

| Other routes/Not known | 567 | 12.4 | 694 | 10.9 | 791 | 10.0 | 1051 | 11.2 | 1281 | 12.9 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 1147 | 25.2 | 1275 | 20.1 | 1408 | 17.8 | 1547 | 16.5 | 1616 | 16.3 |

| Black-Caribbean | 134 | 2.9 | 221 | 3.5 | 306 | 3.9 | 374 | 4.0 | 448 | 4.5 | |

| Black-African | 2749 | 60.4 | 4113 | 64.9 | 5238 | 66.3 | 6214 | 66.4 | 6523 | 65.6 | |

| Black-other | 100 | 2.2 | 143 | 2.3 | 189 | 2.4 | 268 | 2.9 | 304 | 3.1 | |

| Other | 216 | 4.7 | 305 | 4.8 | 427 | 5.4 | 540 | 5.8 | 581 | 5.8 | |

| Not reported | 209 | 4.6 | 283 | 4.5 | 333 | 4.2 | 416 | 4.4 | 470 | 4.7 |

Age varied by ethnicity; compared with black-African women, women of black-Caribbean, black-other or ‘other’ ethnicities were more likely to be in the youngest age group (16-25 years) whilst white women were less likely to be in this group (p<0.001) (data not shown). The proportion of women born in the UK varied by ethnicity (white, 64.3%, 594/924; black-African, 7.3%, 231/2284; black-Caribbean, 38.3%, 88/230, where country of birth was reported).

Pregnancies among women accessing HIV clinical care

There were 1637 pregnancies among 1291 women who accessed care during the period 2000-2009: 1000 (77.5%) women had a single pregnancy, 245 (19.0%) had two and 46 (3.6%) had three or more. The number of pregnancies increased each year, from 72 in 2000 to 230 in 2009.

The number of pregnancies and characteristics of pregnant women under follow-up in each calendar period are presented in Table 2. The proportion of pregnancies which were repeat pregnancies increased from 30.1% (47/156) in 2000/01 to 52.2% (235/450) in 2008/09 (p<0.001), with 735 (44.9%) of the pregnancies being repeat pregnancies overall. Over time there was an increase in the age of pregnant women, with an increase in the proportion over 35 years and a decrease in the proportion aged 26-35 years. The proportion of pregnancies which were repeat pregnancies increased among all age groups (16-25 years, 25.0% (4/16) in 2000/01 to 46.4% (32/69) in 2008/09, p<0.001; 26-35 years, 33.0% (37/112) to 51.3% (139/271), p<0.001 and 36-49 years, 21.4% (6/28) to 58.2% (64/110), p<0.001).

Table 2. Characteristics of HIV-positive pregnant women accessing HIV clinical care at UK CHIC sites in 2000-2009 before their pregnancy.

| Year of conception | 2000/1 | % | 2002/3 | % | 2004/5 | % | 2006/7 | % | 2008/9 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women accessing | 4555 | 6340 | 7901 | 9359 | 9942 | ||||||

| HIV clinical care (16-49 years) | |||||||||||

| Women with a pregnancy | 156 | 3.4 (2.9-4.0) |

250 | 3.9 (3.5-4.4) |

347 |

4.4 (3.9-4.8) |

434 |

4.6 (4.2-5.1) |

450 |

4.5 (4.1-4.9) |

|

| (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||||||||

| Repeat pregnancies | 47 | 30.1 | 90 | 36.0 | 156 | 45.0 | 207 | 47.7 | 235 | 52.2 | |

| Median age (years) (IQR) | 31 | (27-34) | 31 | (27-34) | 31 | (27-35) | 32 | (27-35) | 32 | (28-35) | |

| Age group | 16-25 | 16 | 10.3 | 45 | 18.0 | 56 | 16.1 | 68 | 15.7 | 69 | 15.3 |

| (years) | 26-35 | 112 | 71.8 | 165 | 66.0 | 218 | 62.8 | 266 | 61.3 | 271 | 60.2 |

| 36-49 | 28 | 17.9 | 40 | 16.0 | 73 | 21.0 | 100 | 23.0 | 110 | 24.4 | |

| ART use | On ART | 72 | 46.2 | 127 | 50.8 | 179 | 51.6 | 225 | 51.8 | 287 | 63.8 |

| CD4 count | ≤200 | 31 | 19.9 | 35 | 14.0 | 36 | 10.4 | 44 | 10.1 | 37 | 8.2 |

| (cells/mm3) | 201-350 | 49 | 31.4 | 65 | 26.0 | 98 | 28.2 | 106 | 24.4 | 103 | 22.9 |

| >350 | 74 | 47.4 | 137 | 54.8 | 204 | 58.8 | 264 | 60.8 | 302 | 67.1 | |

| Median CD4 count (cells/mm3) (IQR) |

NK | 2 | 1.3 | 13 | 5.2 | 9 | 2.6 | 20 | 4.6 | 8 | 1.8 |

| 338 | (220-532) | 389 | (257-544) | 401 | (283-564) | 425 | (287-597) | 458 | (321-630) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 35 | 22.4 | 30 | 12.0 | 48 | 13.8 | 42 | 9.7 | 48 | 10.7 |

| Black-Caribbean | 3 | 1.9 | 6 | 2.4 | 14 | 4.0 | 18 | 4.1 | 18 | 4.0 | |

| Black-African | 104 | 66.7 | 182 | 72.8 | 236 | 68.0 | 322 | 74.2 | 329 | 73.1 | |

| Black-other | 5 | 3.2 | 12 | 4.8 | 10 | 2.9 | 11 | 2.5 | 11 | 2.4 | |

| Other | 4 | 2.6 | 7 | 2.8 | 26 | 7.5 | 18 | 4.1 | 20 | 4.4 | |

| Not reported | 5 | 3.2 | 13 | 5.2 | 13 | 3.7 | 23 | 5.3 | 24 | 5.3 |

There was an increase in the proportion of pregnant women on ART (at the start of the year they conceived) (p<0.001). In line with this, among pregnant women, the median CD4 cell count (at start of year) gradually increased over time and the proportion with CD4 <350 cells/mm3 decreased (p<0.001). The proportion of pregnancies among women of black-African or black-Caribbean ethnicity increased (p<0.001) and that among white women decreased (p<0.001) (Table 2). Most pregnancies were among women infected via heterosexual sex (97.0%, 1432/1477, where probable route of exposure was reported), with 1.9% (n=28) among women infected via injecting drug use, 0.7% (n=11) among women infected via MTCT and six among women infected via other routes.

Pregnancy incidence and predictors of pregnancy

Pregnancy incidence was 3.5% (72/2074, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.7-4.3) in 2000 and 4.7% (230/4876, 95% CI 4.1-5.3) in 2009, with the highest incidence in 2006 (4.8%, 216/4528, 95% CI 4.1-5.4). The likelihood that women had a pregnancy increased over the study period (relative rate [RR] per later year: 1.03 [1.01-1.05], p<0.001), this was also the case after controlling for other factors (adjusted RR (aRR) 1.05 [1.03-1.07], p<0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Predictors of pregnancy among HIV-positive women already accessing HIV clinical care at UK CHIC sites in 2000-2009.

| Variables | Person- years |

Pregnancies | Pregnancy rate (per 100 person-years) |

95% CI | Relative Rate |

95% CI | p | Adjusted Relative Rate* |

95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of conception** | 38,097 | 1637 | 4.3 | 4.1 - 4.5 | 1.03 | 1.01-1.05 | <0.001 | 1.05 | 1.03-1.07 | <0.001 | |

| Age group |

16-25 years | 3486 | 254 | 7.3 | 6.4 - 8.1 | 1.12 | 0.98-1.29 | 0.10 | 1.12 | 0.98-1.29 | 0.11 |

| 26-35 years | 15,927 | 1032 | 6.5 | 6.1 - 6.9 | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - | |

| 36-49 years | 18,684 | 351 | 1.9 | 1.7 -2.1 | 0.30 | 0.26-0.34 | <0.001 | 0.29 | 0.25-0.33 | <0.001 | |

| ART use CD4 count (cells/mm3) |

On ART | 22,512 | 890 | 4.0 | 3.7 - 4.2 | 0.82 | 0.74-0.91 | <0.001 | 0.95 | 0.85-1.05 | 0.32 |

| ≤200 | 6073 | 183 | 3.0 | 2.6 - 3.4 | 0.64 | 0.54-0.76 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.55-0.77 | <0.001 | |

| 201-350 | 8841 | 421 | 4.8 | 4.3 - 5.2 | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - | |

| >350 | 21,155 | 981 | 4.6 | 4.4 - 4.9 | 0.98 | 0.87-1.10 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 0.88-1.11 | 0.83 | |

| NK | 2028 | 52 | 2.6 | 1.9 -3.3 | 0.54 | 0.41-0.72 | <0.001 | 0.52 | 0.39-0.68 | <0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 6993 | 203 | 2.9 | 2.5 - 3.3 | 0.62 | 0.52-0.73 | <0.001 | 0.67 | 0.57-0.80 | <0.001 |

| Black-Caribbean | 1483 | 59 | 4.0 | 3.0 - 5.0 | 0.85 | 0.65-1.11 | 0.23 | 0.75 | 0.58-0.97 | 0.03 | |

| Black-African | 24,837 | 1173 | 4.7 | 4.5 - 5.0 | 1.00 | - | - | 1.00 | - | - | |

| Black-other | 1004 | 49 | 4.9 | 3.5 - 6.2 | 1.04 | 0.77-1.39 | 0.81 | 0.94 | 0.71-1.25 | 0.68 | |

| Other | 2069 | 75 | 3.6 | 2.8 - 4.4 | 0.77 | 0.59-0.99 | 0.04 | 0.71 | 0.56-0.91 | 0.01 | |

| Not reported | 1711 | 78 | 4.6 | 3.6 - 5.5 | 0.96 | 0.75-1.23 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.75-1.20 | 0.66 |

Where all variables in the table were included in the model.

As year is a continuous variable, RRs refer to an increase of one year.

There were a number of independent predictors of pregnancy; older women were less likely to have a pregnancy than younger women (aRR 0.44 per 10 year increment in age [95% CI 0.41-0.46], p<0.001) as were women with CD4 <200 cells/mm3 compared with women with CD4 200-350 cells/mm3 (aRR 0.65 [0.55-0.77], p<0.001). Women of white ethnicity were less likely to have a pregnancy than women of black-African ethnicity (aRR 0.67 [0.57-0.80], p<0.001) as were women of black-Caribbean ethnicity after controlling for differences in age, ART use and CD4 count (aRR 0.75 [0.58-0.97], p=0.03). Women infected via injecting drug use were less likely to have a pregnancy than women infected via heterosexual sex (aRR 0.58 [0.35-0.97], p=0.04). In unadjusted analyses, women on ART were less likely to have a pregnancy than women not on ART (RR 0.82 [0.74-0.91], p<0.001) but this was not the case after adjustment for other factors (Table 3).

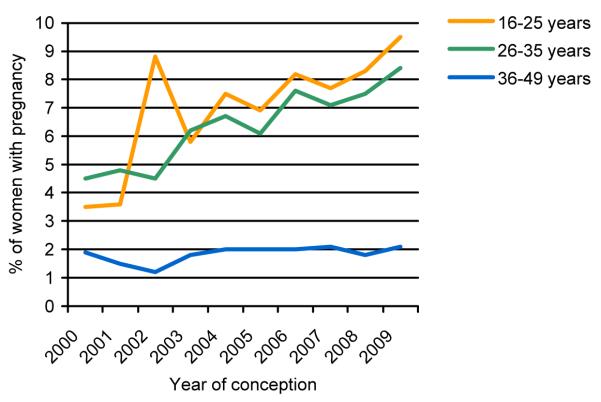

The pregnancy rate increased for women in all age groups (16-25 years, aRR 1.07 per later calendar year [1.02-1.12], p=0.004; 26-35 years, aRR 1.06 [1.04-1.09], p<0.001; 36-49 years, aRR 1.05 [1.00-1.09], p=0.03) (Figure 1). The rate of increase in pregnancy incidence was not significantly different for the three age groups (p-value for interaction=0.15). Similarly, there was an increase in pregnancy rate for all CD4 groups with no evidence that the rate of increase was significantly different for any of these groups (p-value for interaction=0.07). Pregnancy incidence increased among women of black-African ethnicity (aRR 1.06 [1.03-1.08], p<0.001). There was no evidence that the rate of change of pregnancy incidence differed for any ethnic group from that of women of black-African ethnicity, apart from women categorised as ‘black-other’, who experienced a somewhat slower increase in pregnancy rate (p=0.02). As only a small proportion of women with a pregnancy were infected via routes other than heterosexual sex, it was not possible to assess trends in pregnancy rate for different exposure groups. The rate of increase in pregnancy incidence over this period did not significantly differ between women on ART and women not on ART (p-value for interaction=0.14), with predictors of pregnancy being the same regardless of treatment.

Figure 1. Pregnancy incidence in 2000-2009 among women accessing HIV clinical care – by age group.

Pregnancy outcome

The majority of pregnancies resulted in a delivery (86.8%, 1421/1637; 1401 live births and 20 stillbirths) and 193 (11.8%) pregnancies ended early (126 miscarriages, 63 terminations and 4 ectopic pregnancies). Information on pregnancy outcome was unavailable for 8 (0.5%) pregnancies, with a further 15 (0.9%) still ongoing at the time of data submission. Among pregnant women, older women were less likely than younger women to have a pregnancy resulting in delivery (aRR 0.95 [0.92-0.99], p=0.02) and women infected via contaminated blood/blood products were more likely to have a pregnancy resulting in delivery than women infected via heterosexual sex (aRR 1.22 [1.10-1.34], p=0.001). Neither ethnicity, ART use or CD4 count were predictive of whether pregnancy resulted in delivery. The proportion of pregnancies resulting in delivery increased over time (aRR 1.01 [1.00-1.02], p=0.05) and the proportion resulting in a termination decreased, from 12.8% (20/156) in 2000/01 to 2.9% (13/450) in 2008/09, p<0.001.

Discussion

We report an increase in pregnancy rate among HIV-positive women accessing clinical care at 13 large HIV clinics in the UK over the period 2000-2009. Whilst the characteristics of women under HIV care in these clinics changed over this period, in line with changes reported from elsewhere in Europe [16], the increased pregnancy rate in later years remained after adjustment for these characteristics. Of note, there was no evidence that the pregnancy rate increased more among women on ART or among women of a particular age, ethnicity or CD4 category.

increase in pregnancy rate across this diverse group likely to reflect improvements in HIV treatment and management which have led to reduced morbidity [6, 7] and MTCT rates [8, 14]. Changes in pregnancy rates and attitudes towards childbearing following improvements in treatment for both the mother and to prevent MTCTand transmission rates have previously been reported [10, 17, 18] and may also explain the reduction in terminations, also reported elsewhere [17]. Whilst this could also be due to less unplanned pregnancies, thought to be high among this population [19], no data were available on pregnancy intention or use of contraception. It should also be noted that the number of terminations in our study is likely to be an underestimation due to underreporting.

There were a number of characteristics predictive of having a pregnancy. Younger women were more likely to become pregnant than older women, as has been reported from studies of pregnancy rate [17, 20] and pregnancy intention [21, 22] among HIV-positive women. Women infected via injecting drug use were less likely to have a pregnancy than women infected via heterosexual sex, after accounting for age, ethnicity and CD4 count. This has been found elsewhere [22, 24] and is likely to reflect differences in health, lifestyle, desire for children [22] or menstrual changes associated with methadone and illicit drug use [24]. Women of black-African ethnicity were more likely to have a pregnancy than women of white ethnicity or women of black-Caribbean ethnicity. This is likely to be due to cultural differences in attitudes to childbearing and family size. African ethnicity was predictive of fertility intention among HIV-positive women in Canada [21] and France where African born women were more likely to want children than European born women [22]. Differences in pregnancy rate between women of black-African and black-Caribbean ethnicity may reflect cultural differences or differences in the proportion that were UK born.

Women with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3 were less likely to have a pregnancy than women with CD4 200-350 cells/mm3, presumably because these immunosuppressed women had poorer health and were less likely to desire a pregnancy or conceive [23]. As is the case elsewhere in Europe, an increasing proportion of pregnant women conceived whilst using ART [25, 26]. When other factors were considered, ART use did not remain an independent predictor of pregnancy, although it has been found to be in some studies [17, 27]. However, analyses that consider the impact of ART on pregnancy rate may suffer from the problems of time-varying confounding, and can be biased as a result.

In our study the number of pregnancies increased from 156 in 2000/01 to 450 in 2008/09, due to an increase in the number of women accessing and remaining in care [1], and an increase in the likelihood that women became pregnant. Among all HIV-positive women in the UK and Ireland, including those diagnosed during pregnancy, the number of pregnancies stabilised in 2006 at around 1500 pregnancies per year [28], when pregnancy incidence in our study was highest (4.8%). This plateau may, in part, be due to a reporting delay, but could also be due to the increasing number of older women accessing care, women who, in general, are less likely to become pregnant.

As the number of pregnancies has risen, so has the use of specialist antenatal services. All HIV-positive women who are pregnant or planning a pregnancy require a high level of clinical care from a multidisciplinary team including specialist midwives, obstetricians, HIV specialists, GPs, paediatricians and health workers. Many women also require additional support in areas such as assisted reproduction, ART adherence, advice regarding HIV disclosure and social/immigration issues [29]. Demand for these services is likely to increase further, particularly as an increasing number of older women have pregnancies (as is the case in the UK population [30]). Older women may require additional support, particularly those over 40, as they are at increased risk of experiencing fertility problems [31] and complications such as preterm delivery[31], pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes [32], complications also associated with antenatal ART use[25, 33-36]. An increase in the number of older pregnant women, whose infants are at increased risk of neural tube defects [39] and Down’s syndrome [40] may also lead to an increase in the use of invasive diagnostics. Older maternal age and HIV have both also been associated with an increased risk of stillbirth [41] and miscarriage [38, 42]. In our study older pregnant women were more likely to have a pregnancy which ended early.

As well as implications for HIV and antenatal services, the increased pregnancy rate among HIV-positive women receiving care has implications for the women and their children. Although MTCT in the UK is now rare among diagnosed women, with a transmission rate of 1.2% in 2000-2006 [14], an increasing number of infants are at risk of transmission and exposed to ART drugs in utero. Increasingly ART exposure is for the full duration of pregnancy. The long-term implications of ART exposure, particularly to newer drugs, are not fully understood and are difficult to monitor [37]. For HIV-positive women, pregnancy has become increasing normal and many can fulfil their desire for a ‘normal’ family life. Questions remain regarding the direct and indirect effects of pregnancy on HIV progression including the long-term impact of exposure to ART used for PMTCT during pregnancies on the women’s health and future treatment responses [38, 39].

There were a number of limitations to the data available for analysis. Some possible predictors of pregnancy, such as parity, were not available in UK CHIC, and as such were not included in the analysis. Pregnancies during which HIV was diagnosed were not included in the analysis and factors predictive of pregnancy among women not aware of their HIV status may differ from those of diagnosed women. Also, the first CD4 count in the year and ART use at start of the year were used and these may have changed by the time the woman conceived. ART status did not take into account whether the woman was on ART for her own health or for PMTCT during an earlier pregnancy. Women whose pregnancies ended in termination or first trimester miscarriage may not have accessed antenatal care, and therefore not been reported to the NSHPC. As such, the proportion of pregnancies ending early is likely to be a minimum estimate and despite there being no significant change in the rate of miscarriages among reported pregnancies there may have been changes in the rate during this period.

As both datasets are pseudonymised, finding records for women reported to both studies relied on using demographic and clinical variables available from both studies. As a result here is likely to be incomplete linkage of the datasets and an underestimation of pregnancy incidence. However, any such underestimation is unlikely to affect our assessment of the predictors of pregnancy or trends over time. A higher proportion of women in the UK CHIC dataset accessed care in London than is the case nationally, although a direct comparison was not possible. The characteristics of pregnant women accessing care in London may differ from those accessing care elsewhere but trends in pregnancy incidence are likely to be similar.

Conclusion

An increase in pregnancies among women accessing HIV-clinical care reflect increases in the pregnancy rate among this group as well as increases in the number of women accessing care. HIV-positive women with or planning a pregnancy require a high level of clinical care and this is likely to continue particularly as more older women have pregnancies.

Acknowledgments

UK CHIC: Steering Committee: Jonathan Ainsworth, Jane Anderson, Abdel Babiker, David Chadwick, Valerie Delpech, David Dunn, Martin Fisher, Brian Gazzard, Richard Gilson, Mark Gompels, Phillip Hay, Teresa Hill, Margaret Johnson, Stephen Kegg, Clifford Leen, Mark Nelson, Chloe Orkin, Adrian Palfreeman, Andrew Phillips, Deenan Pillay, Frank Post, Caroline Sabin (PI), Memory Sachikonye, Achim Schwenk, John Walsh.

Central Co-ordination: UCL Research Department of Infection & Population Health, Royal Free Campus, London (Teresa Hill, Susie Huntington, Sophie Josie, Andrew Phillips, Caroline Sabin, Alicia Thornton); Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit (MRC CTU), London (David Dunn, Adam Glabay).

Participating Centres: Barts and The London NHS Trust, London (C Orkin, N Garrett, J Lynch, J Hand, C de Souza); Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust (M Fisher, N Perry, S Tilbury, D Churchill); Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Trust, London (B Gazzard, M Nelson, M Waxman, D Asboe, S Mandalia); Health Protection Agency – Centre for Infections London (HPA) (V Delpech); Homerton University Hospital NHS Trust, London (J Anderson, S Munshi); King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London (H Korat, J Welch, M Poulton, C MacDonald, Z Gleisner, L Campbell); Mortimer Market Centre, London (R Gilson, N Brima, I Williams); North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust, London (A Schwenk, J Ainsworth, C Wood, S Miller); Royal Free NHS Trust and UCL Medical School, London (M Johnson, M Youle, F Lampe, C Smith, H Grabowska, C Chaloner, D Puradiredja); St. Mary’s Hospital, London (J Walsh, J Weber, F Ramzan, N Mackie, A Winston); The Lothian University Hospitals NHS Trust, Edinburgh (C Leen, A Wilson); North Bristol NHS Trust (M Gompels, S Allan); University of Leicester NHS Trust (A Palfreeman, A Moore); South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (D Chadwick, K Wakeman).

NSHPC:

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the midwives, obstetricians, genitourinary physicians, paediatricians, clinical nurse specialists and all other colleagues who report to the NSHPC through the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the obstetric reporting scheme run under the auspices of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. We thank Janet Masters who coordinates the study and manages the data and Icina Shakes for administrative support.

Ethics approval for NSHPC was renewed following review by the London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee in 2004 (MREC/04/2/009).

Sources of Funding:

UK CHIC is funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC), UK (grants G00001999 and G0600337). NSHPC receives core funding from the Health Protection Agency (grant number GHP/003/013/003). Data is collated at the UCL Institute of Child Health which receives a proportion of funding from the Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. Susie Huntington has a UCL Studentship, funded by the MRC, for postgraduate work. Claire Thorne holds a Wellcome Trust Research Career Development Fellowship.

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the researchers and not necessarily those of the funders.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

Reference List

- 1.Health Protection Agency . SOPHID: Accessing HIV care national tables: 2010. [Last accessed April 2012]. 2011. Available at www.hpa.org.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Protection Agency . HIV in the United Kingdom: 2011 Report. [Last accessed April 2012]. 2011. Available at www.hpa.org.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gazzard BG, BHIVA Treatment Guidelines Writing Group British HIV Association Guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-infected adults with antiretroviral therapy 2008. HIV Med. 2008;9(8):563–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sterne JA, May M, Costagliola D, de WF, Phillips AN, Harris R, et al. Timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-free HIV-1-infected patients: a collaborative analysis of 18 HIV cohort studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60612-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clumeck N, Pozniak A, Raffi F. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guidelines for the clinical management and treatment of HIV-infected adults. HIV Med. 2008;9(2):65–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May M, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Post F, Johnson M, et al. Impact of late diagnosis and treatment on life expectancy in people with HIV-1: UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) Study. BMJ. 2011;343:d6016. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Collaborative Study Mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(3):458–465. doi: 10.1086/427287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, Tookey PA. Trends in management and outcome of pregnancies in HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, 1990-2006. BJOG. 2008;115(9):1078–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cliffe S, Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Newell ML. Fertility intentions of HIV-infected women in the United Kingdom. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1093–1101. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French CE, Cortina-Borja M, Thorne C, Tookey PA. Incidence, Patterns, and Predictors of Repeat Pregnancies Among HIV-Infected Women in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 1990-2009. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):287–293. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823dbeac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agangi A, Thorne C, Newell ML. Increasing likelihood of further live births in HIV-infected women in recent years. BJOG. 2005;112(7):881–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UK Collaborative HIV Cohort Steering Committee The creation of a large UK-based multicentre cohort of HIV-infected individuals: The UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) Study. HIV Med. 2004;5(2):115–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, Tookey PA. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000-2006. AIDS. 2008;22(8):973–981. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f9b67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huntington SE, Bansi LK, Thorne C, Anderson J, Newell ML, Taylor GP, et al. Treatment switches during pregnancy among HIV-positive women on antiretroviral therapy at conception. AIDS. 2011;25(13):1647–1655. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834982af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudin C, Spaenhauer A, Keiser O, Rickenbach M, Kind C, Aebi-Popp K, et al. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and premature birth: analysis of Swiss data. HIV Med. 2011;12(4):228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massad LS, Springer G, Jacobson L, Watts H, Anastos K, Korn A, et al. Pregnancy rates and predictors of conception, miscarriage and abortion in US women with HIV. AIDS. 2004;18(2):281–286. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401230-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, Feldman JG, Golub ET, Schmidt J, Silver S, Robison E, et al. Live birth patterns among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women before and after the availability of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(6):541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fiore S, Heard I, Thorne C, Savasi V, Coll O, Malyuta R, et al. Reproductive experience of HIV-infected women living in Europe. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(9):2140–2144. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loutfy MR, Hart TA, Mohammed SS, Su DS, Ralph ED, Walmsley SL, et al. Fertility Desires and Intentions of HIV-Positive Women of Reproductive Age in Ontario, Canada: A Cross-Sectional Study. Plos One. 2009;4(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craft SM, Delaney RO, Bautista DT, Serovich JM. Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. Aids and Behavior. 2007;11(6):927–935. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heard I, Sitta R, Lert F. Reproductive choice in men and women living with HIV: evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study) AIDS. 2007;21:S77–S82. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255089.44297.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harlow SD, Cohen M, Ohmit SE, Schuman P, Cu-Uvin S, Lin X, et al. Substance use and psychotherapeutic medications: a likely contributor to menstrual disorders in women who are seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(4):881–886. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blair JM, Hanson DL, Jones JL, Dworkin MS. Trends in pregnancy rates among women with human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):663–668. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000117083.33239.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudin C, Spaenhauer A, Keiser O, Rickenbach M, Kind C, Aebi-Popp K, et al. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and premature birth: analysis of Swiss data. HIV Med. 2011;12(4):228–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baroncelli S, Tamburrini E, Ravizza M, Dalzero S, Tibaldi C, Ferrazzi E, et al. Antiretroviral treatment in pregnancy: a six-year perspective on recent trends in prescription patterns, viral load suppression, and pregnancy outcomes. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(7):513–520. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman RK, Bastos FI, Leite IC, Veloso VG, Moreira RI, Cardoso SW, et al. Pregnancy rates and predictors in women with HIV/AIDS in Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil. Revista de Saude Publica. 2011;45(2):373–381. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102011000200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NSHPC . Routine NSHPC Quarterly Slides. [Last accessed April 2012]. Oct, 2011. Available at www.nshpc.ucl.ac.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Ruiter A, Taylor G, Palfreeman A, Clayden P, Dhar J, Gandhi K, et al. Guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women 2012. Jan, 2012. Draft 1. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office for National Statistics . Statistical Bulletin: Births and Deaths in England and Wales, 2010. [Last accessed April 2012]. 2011. Available at www.ons.gov.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baird DT, Collins J, Egozcue J, Evers LH, Gianaroli L, Leridon H, et al. Fertility and ageing. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11(3):261–276. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aebi-Popp K, Lapaire O, Glass TR, Vilen L, Rudin C, Elzi L, et al. Pregnancy and delivery outcomes of HIV infected women in Switzerland 2003-2008. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(4):353–358. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Townsend C, Schulte J, Thorne C, Dominguez KI, Tookey PA, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and preterm delivery-a pooled analysis of data from the United States and Europe. BJOG. 2010;117(11):1399–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suy A, Martinez E, Coll O, Lonca M, Palacio M, de LE, et al. Increased risk of pre-eclampsia and fetal death in HIV-infected pregnant women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2006;20(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000198090.70325.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez-Tome MI, Ramos Amador JT, Guillen S, Solis I, Fernandez-Ibieta M, Munoz E, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus in a cohort of HIV-1 infected women. HIV Med. 2008;9(10):868–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de la Rochebrochard E, Thonneau P. Paternal age and maternal age are risk factors for miscarriage; results of a multicentre European study. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(6):1649–1656. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.6.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hankin C, Lyall H, Willey B, Peckham C, Masters J, Tookey P. In utero exposure to antiretroviral therapy: feasibility of long-term follow-up. AIDS Care. 2009;21(7):809–816. doi: 10.1080/09540120802513717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minkoff H, Hershow R, Watts DH, Frederick M, Cheng I, Tuomala R, et al. The relationship of pregnancy to human immunodeficiency virus disease progression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(2):552–559. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watts DH, Lu M, Thompson B, Tuomala RE, Meyer WA, III, Mendez H, et al. Treatment interruption after pregnancy: effects on disease progression and laboratory findings. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2009:456717. doi: 10.1155/2009/456717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]