Abstract

Background

Many psychological traits become increasingly influenced by genetic factors throughout development, including several which might intuitively be seen as purely environmental characteristics. One such trait is the parent-child relationship, which is associated with a variety of socially significant outcomes, including mental health and criminal behavior. Genetic factors have been shown to partially underlie some of these associations, but the changing role of genetic influence over time remains poorly understood.

Method

Over 1,000 participants in a longitudinal twin study were assessed at three points across adolescence with a self-report measure regarding the levels of warmth and conflict in their relationships with their parents. These reports were analyzed with a biometric growth curve model to identify changes in genetic and environmental influences over time.

Results

Genetic influence on the child-reported relationship with parent increased throughout adolescence, while the relationship’s quality deteriorated. The increase in genetic influence resulted primarily from a positive relation between genetic factors responsible for the initial relationship and those involved in change in the relationship over time. In contrast, environmental factors relating to change were negatively related to those involved in the initial relationship.

Conclusions

The increasing genetic influence appears due to early genetic influences having greater freedom of expression over time, while environmental circumstances were decreasingly important to variance in the parent-child relationship. We infer that the parent-child relationship may become increasingly influenced by the particular characteristics of the child (many of which are genetically-influenced), gradually displacing the effects of parental or societal ideas of child-rearing.

Introduction

A developing body of behavioral genetic research has demonstrated significant genetic influence on a range of purportedly environmental variables. Kendler and Baker (2007) reported a range of studies on the topic showing modest to moderate genetic impact on phenomena such as stressful life events, marital quality, peer interactions, and parent-child relationships. As each of these traits is clearly affected by more conventional genetically-influenced traits like personality, mental health and intelligence, the discovery of non-zero heritability estimates for such traits should not be surprising in itself. However, studies demonstrating these effects may be of particular interest for researchers in psychopathology because of their power to illustrate the potential for “outside-the-skin” pathways for genetic influence on psychopathology, in which the impact of genes on disease risk is mediated by genetically-influenced pathogenic environments. Longitudinal studies on the impact of genetic factors on purportedly environmental variables are crucial for identifying such mediation effects, though Kendler and Baker (2007) lamented that few such studies exist.

One ongoing effort that addresses this deficit is the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), a longitudinal twin study that has explored the role of genetic factors in the parent-child relationship (Elkins et al, 1997; McGue et al, 2005) and how this relationship contributes to externalizing psychopathology (Burt et al, 2005). The latter study demonstrated one “outside-the-skin” pathway when it showed that genetic factors affecting the early expression of a purportedly environmental variable (the parent-child relationship) contributed to levels of externalizing behaviors exhibited at a later age. The connection of the parent-child relationship with psychopathology and criminal behavior has long been recognized (cf Rothbaum & Weisz, 1994), but the ability of Burt and colleagues to control for confounding genetic factors enabled them to demonstrate that the individual plays some role in the emergence of the environmental risk itself.

While the role of genetic influence in the parent child relationship has been explored extensively by several investigators (Kendler, 1996; Reiss, Neiderhiser, Hetherington, & Plomin, 2000; Rowe, 1981, 1983), newer contributions have focused on the change in heritability for this phenotype over time. Using a cross-sectional design, Elkins et al. (1997) found far greater heritability estimates for the parent-child relationship in the late-adolescent cohort of the MTFS than for the pre-adolescent cohort. This work was supported by later longitudinal data from the MTFS presented by McGue et al. (2005), who found increased heritability on the same measure between ages 11 and 14. Both of these studies contributed to a growing literature in behavioral genetics concerning change in heritability over time. A recent summary and meta-analysis by Bergen et al. (2007) showed that increased heritability was observed from childhood to adulthood in all domains examined, including mental disorders, intellectual functioning, social and political attitudes, and family relations. These increases in heritability tend to come at the expense of shared environmental contributions (i.e., the environmental effects associated with growing up together in the same family), whose role in influencing individual differences often begins to diminish well before the age when children typically leave the home.

Nevertheless, the growing recognition of biometric trends in development has remained significantly agnostic as to the processes responsible for them. While this topic may ultimately be addressed at the molecular level, quantitative behavioral genetic methods can provide insight into the processes involved by clarifying the manner in which genetic influences on the phenotype change over time. Plomin (1986) noted that while genetic factors account for much less variance in IQ at early ages than in adulthood, there were indications of a high degree of overlap in the genetic factors involved throughout this period. This suggested that genetic factors accounted for increasing amounts of variance through a process he termed genetic amplification, in which initial genetic effects acquire greater influence as the individual ages. Alternatively, change in heritability estimates over the developmental course could indicate that some genetic factors influence the phenotype only at particular ages. In the context of increasing heritability this might be termed genetic addition, as these genetic factors would increase the net influence of genes on a phenotype without any necessary relation to earlier genetic influences on the trait. A final possibility is that raw variance due to non-genetic sources declines through development, leading to an increase in heritability estimates even in the absence of any increase in variance due to genetic factors. Identifying which alternative is responsible for the biometric course of a trait allows one to make some inferences as to the nature and influence of certain sources of phenotypic variation, as outlined below.

Conventional biometric models are sufficient to identify heritability changes that result from decreasing environmental variance. However, differentiating between the two alternatives in which genetic variance increases throughout development is best accomplished via growth curve modeling, a statistical technique available only to longitudinal studies with three or more assessments of the trait. When applied to a genetically informative sample like twins, such models can identify both whether and how much genetic and environmental factors contribute to change and stability in the phenotype over time, as well as what forms those contributions take. Some contributions of genetic and environmental factors may be specific to a single time point, and growth curve models isolate these contributions as age-specific effects. Biometric contributions that are part of a continuous trend throughout development are identified by their effects on the initial level (intercept), changes in that level (slope), and the relation between those two (intercept-slope covariance).

Under the amplification model, a strong genetic association between the intercept and slope is expected, as this would indicate a growing importance for genetic influences on change that were already contributing to the phenotype when first assessed. In contrast, if the genetic association between intercept and slope is weak, and either a strong genetic influence is found for slope or large age-specific genetic effects are found in later assessments, the increased heritability can be attributed to genetic addition. While there exist empirical demonstrations for the latter process (Hjelmborg et al., 2008), amplification has a more plausible theoretical grounding for psychological phenotypes. This is because individuals are generally thought to have greater freedom to act in accord with genetic dispositions as they age (Scarr & McCartney, 1983) and become less constrained by the influences of their parents. Thus, for any traits in which genetic factors increase in importance because of the increasing freedom of the individual to express his or her dispositions, latent growth modeling may be expected to identify genetic amplification at the heart of increasing genetic variance for the trait.

For the parent-child relationship, this could be interpreted as the relationship becoming more individualized and responsive to the particular genetically-influenced characteristics of the child, which gradually displace the effects of parental or societal conceptions of child-rearing. Genetic amplification also indicates that such child characteristics already influencing deviation from the mean at an early age have increasing effects over time, so that those who are relatively extreme tend to become more extreme. In contrast, in genetic addition any change in individual differences derived from genetic factors may be unrelated or even negatively related to initial individual differences resulting from genetic factors.

We examined MTFS data on the parent-child relationship in a large longitudinal sample assessed at ages 11, 14 and 17 to identify phenotypic changes in this relationship and characterize any biometric patterns over this period. Although previous research has suggested that the parent-child relationship stabilizes in later adolescence (e.g. Kim et al., 2001; Loeber et al., 2000), these studies typically included only a few hundred participants and so may have been underpowered.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of participants from the MTFS, an ongoing community-based longitudinal study of reared-together, same-sex twins and their parents. Readers are referred to Table 1 for the number and gender breakdown of participants. Comprehensive descriptions of this study’s procedures and sample characteristics have been provided elsewhere (cf. Iacono et al., 1999; Iacono & McGue, 2002).

Table 1.

Twin correlations (95% confidence interval) for the Parent Environment Questionnaire (PEQ) at ages 11, 14 and 17.

|

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Pooled | ||||

| MZ | DZ | MZ | DZ | MZ | DZ | |

| Age 11 | .55 (.45–.64) | .40 (.22–.55) | .41 (.29–.51) | .44 (.30–.57) | .48 (.40–.55) | .42 (.31–.52) |

| Age 14 | .56 (.46–.64) | .43 (.26–.58) | .54 (.44–.63) | .48 (.38–.61) | .55 (.48–.62) | .46 (.35–.56) |

| Age 17 | .60 (.50–.69) | .29.08–.47) | .54 (.43–.64) | .30 (.12–.46) | .57 (.49–.63) | .29 (.16–.42) |

|

| ||||||

| N at 11 | 238 | 218 | 225 | 221 | 563 | 439 |

| N at 14 | 220 | 216 | 211 | 210 | 436 | 416 |

| N at 17 | 180 | 187 | 195 | 192 | 375 | 379 |

Note: Correlations were estimated using the EM algorithm assuming unobserved data was missing at random.

The present sample was first assessed at age 11 (M 11.7 years, SD 0.43), with follow-up assessments performed approximately three years later, and then again three years after that. While only 73% of the twins completed the relevant assessment at all three time points, another 20% were assessed twice. Analysis of information provided at age 11 by those not present in later assessments showed that while a composite score of externalizing symptoms did not predict non-participation at age 14, it did predict non-participation at age 17, with non-participants scoring .4 SD higher on age 11 externalizing symptoms. Scores from other assessments at that age, including internalizing symptoms and parent-child relationship quality, did not predict later participation in the study.

Measures

Data on the parent-child relationship were gathered at each assessment when the twins completed the Parent Environment Questionnaire (PEQ) for each rearing parent. The PEQ is a 42-item survey developed by MTFS researchers to measure the relationship of the child with each parent; representative items include “My parent often criticizes me” and “My parent comforts me when I am discouraged or have had a disappointment.” Elkins et al. (1997) provided a description of the development, theoretical rationale and psychometric properties of the PEQ, noting that factor analyses suggest the PEQ primarily assesses one major dimension of the parent-child relationship, which we follow McGue et al. (2005) in interpreting as concerned with parental warmth versus conflict. Previous work with the PEQ (Elkins et al. 1997, McGue et al. 2005) has examined this dimension using four different scales (Conflict, Involvement, Parental Regard for Child, and Child Regard for Parent). These scales are all highly correlated (between .59 and .70) and a principal components analysis of the constitutive items showed a first component accounting for more than 33% of the variance while the second factor accounted for less than 6%. Accordingly, for the present analysis we summed the raw scores on these four scales (after reverse-scoring the Conflict scale) to form a unitary factor scale in which high scores reflect a more positive relationship.

Consistent with previous research based on self-report (Juang & Silbereisen, 1999) and direct observation (Baumrind, 1991; Kim et al., 2001), children’s ratings of their relationships with their mothers and their relationships with their father were highly correlated. For both boys and girls, the correlations between mother and father ratings exceeded .60 at every assessment. For the analyses reported here we thus followed procedures used in other studies (e.g. McGue et al., 2005) by averaging participants’ ratings of relationships with mother and father to form a parent composite. In cases where there was only one rearing parent, the participant’s ratings for that parent were used.

Statistical Methods

Analysis of the longitudinal twin data was based on standard biometric methods (Neale & Cardon, 1992). That is, we assumed that the total phenotypic variance (P) for a given scale could be decomposed into independent additive genetic (A), shared environmental (C), and unique environmental (E) components. Additive genetic factors influence phenotypes without regard to other genes (i.e. epistatic effects) and are not expressed in dominant and recessive alleles. Shared environment refers to aspects of the environment that have similar effects on the phenotype of interest in each twin, regardless of zygosity. Non-shared environment refers to environmental variables that cause phenotypic differences between the members of a twin pair. Because MZ twins share 100% of additive genetic effects whereas DZ twins share only 50%, and because shared environmental effects are assumed to contribute equally to the similarity of the two types of twins, the three variance components (A, C, and E) can be estimated from the observed variances and covariances for the two types of twins. The rationale and empirical support for the assumptions that underlie application of the standard biometric model to twin data have been extensively discussed and justified elsewhere (Johnson et al., 2002; Kendler et al., 2001; Pike et al., 1996; Plomin et al., 1997). Nonetheless, we recognize that because we cannot directly establish the validity of these assumptions in the present application, the estimates of the variance components we report should be considered approximate.

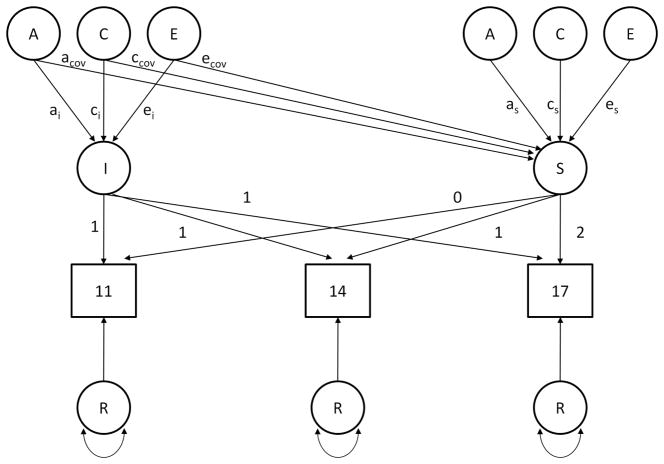

Biometric latent growth curve modeling was used to examine the changing contributions of A, C and E over time (Neale & McArdle, 2000). The full biometric growth curve model is depicted in Figure 1. In this model, the variance in parental-child relationships over time was decomposed into four portions: contributions to intercept (I), slope (S), the covariance between the two, and contributions specific to each assessment (R). These were then decomposed into their respective additive genetic, shared environmental, and non-shared environmental components. Contributions to the intercept (ai, ci, and ei) comprised variance in the parent-offspring relations that were stable across assessments, i.e. they contributed to the phenotype equally at each evaluation. Slope estimates (as, cs, and es) represented the roles of the factors in linear change across assessments. Covariance estimates (acov, ccov, and ecov) represent the relationship between factors contributing to initial level and change. One of the merits of growth curve models is that by modeling intercept and slope as latent factors, non-shared environmental influences were not confounded with measurement error. Instead, effects of measurement error showed themselves in the contributions specific to single assessments. (As these can be thought of as the contributions not captured by the general regression terms, they are referred to as residuals.) These were estimated for each factor and for each assessment age.

Figure 1.

Path-diagram of linear ACE growth curve model (for one individual) centered on age at initial assessment. Letters A, C, and E denote additive genetic, common environmental, and unique environmental effect, respectively. I and S denote level at baseline (intercept) and rate of change (slope), respectively, and R denotes the residual effect. Intercept-slope covariance is represented by the path connecting the A, C, and E intercept estimators and the slope.

Even though attrition from the MTFS sample at follow-up was not related to PEQ, we accommodated missing data using Full-Information Maximum-Likelihood raw data techniques (FIML), which produce efficient and consistent estimates in the presence of missing data (Little & Rubin, 1987).

Using the Mx software system (Neale et al., 2003) we obtained fit statistics for growth curve models (Neale & McArdle, 2000) of PEQ data for three models. The first of these was a no-sex-differences model in which parameter estimates for the male and female samples are constrained to be equal. Our second was a scalar-sex-differences model, which allows the variance-covariance estimates in the male and female samples to differ only by a freely estimated scalar. Finally, we also estimated an unconstrained model in which parameters were freely estimated in the two samples. Following the guidelines in Markon and Krueger (2004) based on sample size, biometric composition and skewness, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1973) was the preferred fit statistic.

Results

Change and Stability Across Assessments

McGue et al. (2005) found that the parent-child relationship deteriorated between ages 11 and 14 in the MTFS sample, with increased levels of conflict and declining levels of involvement and mutual regard. We saw a modest continued deterioration in this relationship between ages 14 and 17. SAS Proc Mixed indicated that the decline in mean PEQ score between age 14 (mean=63.41, sd=15.19) and age 17 (mean=62.71, sd=15.48) was significant at p<.05, with a Cohen’s d of .05. There was no significant sex difference (p=.91) or age by-sex interaction (p=.36).

The stability coefficients for the PEQ suggested moderate stability for the phenotype over time: with boys and girls analyzed together, we found a correlation of .44 between age 11 and 14, .52 between 14 and 17, and .29 between 11 and 17.

Twin Correlations

While growth curve models are more informative for data such as ours, a brief look at the twin correlations helps highlight important patterns. Maximum-likelihood estimates of the twin correlations at each assessment are provided in Table 1, with boys and girls evaluated both separately and pooled. There were two trends worth comment. First, MZ-DZ differences in correlation strength were more pronounced in boys than girls across all time points, suggesting possible stable sex difference in the heritability of the parent-child relationship. Second, the MZ correlations were generally greater than the corresponding DZ correlations, a trend that increased markedly as the sample aged. The biometric models were needed, however, to determine how differences in correlations corresponded to changes in the components of phenotypic variance over time.

Biometric Analysis

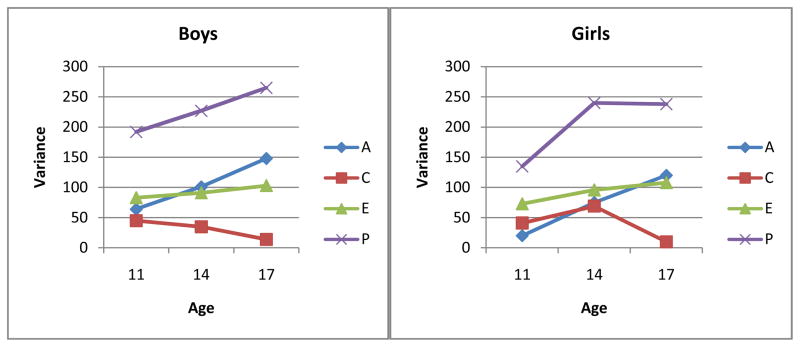

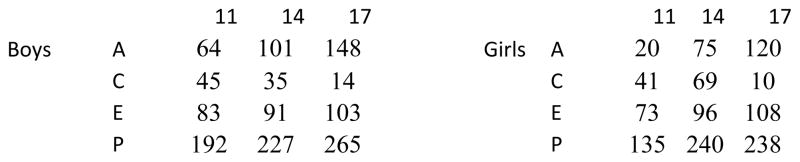

A superior fit was indicated by AIC values for the unconstrained model (22674.90) compared to both the no-sex-differences model (22683.99) and the scalar-sex-differences model (22685.98), suggesting that the biometric presentation of the parent-child relationship differed between boys and girls. While boys increased in phenotypic variance between each assessment, increase in variance for girls was complete by age 14. The lack of fit of a scalar-sex-differences model indicates that these different patterns, rather than a general sex difference in variance, are responsible for the improved fit observed when treating sexes separately. Common to both boys and girls was a substantial increase in raw genetic variance between each assessment, as well as a decrease in raw shared environmental variance between 11 and 17 and modest increase in unique environmental variance. The resulting standardized biometric estimates are shown in Table 2, showing substantial increases in heritability estimates, with corresponding declines in shared environmental factors.

Table 2.

Standardized ACE estimates from Growth Curve

| 11 | 14 | 17 | I | S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Boys | .37 (.14–.60) | .44 (.20–.65) | .56 (.31–.68) | .50 (.19–.89) | .08 (.00–.65) |

| Girls | .14 (.00–.43) | .34 (.06–.62) | .49 (.15–.63) | .21 (.01–.63) | .17 (.00–.63) | |

|

| ||||||

| C | Boys | .20 (.00–.42) | .16 (.00–.39) | .05 (.00–.28) | .28 (.00–.59) | .44 (.00–.67) |

| Girls | .32 (.06–.46) | .26 (.01–.49) | .05 (.00–.36) | .43 (.03–.67) | .30 (.00–.63) | |

|

| ||||||

| E | Boys | .43 (.35–.52) | .40 (.33–.49) | .39 (.31–.49) | .22 (.05–.39) | .48 (.26–.72) |

| Girls | .55 (.45–.64) | .41 (.33–.51) | .46 (.37–.57) | .36 (.18–.58) | .52 (.25–.85) | |

Note: Biometric estimates for each age represent the standardization of the results depicted in Figure 2. Estimates for biometric contributions to intercept (I) and slope (S) are standardized values from Table 3. A, C and E parameters sum to 100 for any group, and represent the percent of the variance accounted for by that parameter. A = additive genetic component of variance; C = shared environmental; E = nonshared

Supplementary analyses were completed to characterize the growth curve results further. We used a Cholesky model (Neale & Cardon, 1992) to test whether genetic variance increased between ages 11 and 17 formally, in absolute and relative terms. Neither the raw nor standardized genetic variance could be constrained across time without loss of fit as measured by AIC, indicating the significance of these changes (unconstrained model AIC: 15088.185; raw genetic variance constrained AIC: 15092.363; standardized genetic variance constrained AIC: 15089.292). Despite the increase in genetic variance, the estimated genetic correlation between ages 11 and 17 remained very high (.95 [95% CI = .04, 1.00] in females and .90 [.46, 1.00] in males) and not significantly different from 1.0. Increasing genetic variance accompanied by high genetic correlations is consistent with a model of genetic amplification. McGue et al. (2005) previously reported this pattern for this sample when comparing ages 11 and 14, but the addition of age 17 data allows us to explore these patterns further using growth curve modeling.

Parameter estimates from the growth curve model are presented in Table 3 and accounted for the distinct patterns of change in genetic and environmental variance components depicted in Figure 2. Several aspects of this table are worth highlighting. First, the genetic covariance parameter (Boys=16.65, Girls=12.04) was positive and large compared to the genetic slope parameter (Boys=4.34, Girls=6.99) and the age-specific genetic residuals (all less than 5.0). The increase in genetic variance over time seen in Figure 2 was thus primarily a result of the positive correlation between the genetic factors contributing to initial differences and those contributing to change. That is, genetic amplification was present. Second, the shared environmental covariance parameter was negative (Boys=−29.34, Girls=−22.11) and larger in absolute value than the corresponding shared environmental slope parameter (Boys=23.96, Girls=12.45), while the age-specific shared environmental variances were uniformly small (all less than 8.0). The decrease in variance shared environmental variance over time seen in Figure 2 was the result of the negative correlation between initial values and change. Finally, the non-shared environmental covariance parameter was negative (Boys=−12.18, Girls=−15.35) and smaller in absolute value than the corresponding non-shared environmental slope parameter (Boys=25.63, Girls=20.84), while the age-specific non-shared environmental variances were relatively constant across the three ages. The slight increase in non-shared environmental variance observed in Figure 2 was a result of large non-shared environmental contributions to change (i.e., the slope), which more than compensated for the negative correlation between initial values and change.

Table 3.

Growth-curve parameter estimates for the Parent Environment Questionnaire (PEQ)

| Intercept (I) | Slope (S) | Covariance (I, S) | Age-Specific Contributions

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 11 | Age 14 | Age 17 | |||||

| Boys | A | 63.86 | 4.34 | 16.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.54 |

| C | 35.93 | 23.96 | −29.34 | 2.97 | 5.81 | 0.00 | |

| E | 27.79 | 25.63 | −12.18 | 7.46 | 7.84 | 4.59 | |

| P | 127.58 | 53.93 | −24.87 | 10.43 | 13.65 | 5.13 | |

|

| |||||||

| Girls | A | 20.73 | 6.99 | 12.04 | 0.00 | 4.81 | 4.80 |

| C | 40.88 | 12.45 | −22.11 | 0.00 | 7.74 | 2.81 | |

| E | 34.38 | 20.84 | −15.35 | 6.24 | 8.45 | 7.19 | |

| P | 95.99 | 40.28 | −25.42 | 6.24 | 21.00 | 14.80 | |

Note. Results from the growth-curve model for each biometric parameter (A, C, E), which sum to provide the complete phenotypic growth-curve results (P).

Figure 2.

Unstandardized Variance Components derived from Growth-Curve Model

Note. Original unstandardized values of the biometric variance components derive from the parameter estimates from the growth curve model represented in Table 3. A = additive genetic component of variance; C = shared environmental; E = nonshared environmental; P= total phenotypic variance.

Discussion

We identified a change in relationship quality between parent and child between ages 14 and 17, though consistent with the results from other samples (e.g. Loeber et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001) the observed deterioration (d of .05) was considerably smaller than that reported by McGue et al. (2005) in the same sample between ages 11 and 14. Throughout adolescence we observed increasing genetic influences on this relationship, accompanied by a decline in the importance of shared environment. The biometric changes occurred primarily because genetic factors that contributed to the initial phenotype exerted increasing influence on the phenotype over time, with the result that early individual differences on the phenotype due to genetic effects extended their influence over time. This pattern contrasted with the trend found for the broader phenotype as well as shared and unique environmental factors, each of which indicated that those with extreme initial parent-child relationships experienced less change than did those who had more average initial relationships. In the context of the deteriorating parent-child relationship over this period, this may indicate that those with particularly poor relationships at 11 did not experience as sharp a deterioration in that relationship as did those whose relationship at 11 had more warmth and involvement.

There are several important limitations to consider when interpreting the results of this study. First, the study involved only adolescent self-reports on their relationships with their parents. Thus, it is possible that part of the increase in heritability represents increasing roles of genetic factors in how individuals process, interpret and report their relationships with their parents, rather than changes in those relationships themselves. Self-report measures of parenting are only modestly correlated with measures based on direct observation (Holden & Edwards, 1989). Further, because parent reports may be influenced by ideals of equal treatment for children and method-based reporting problems, previous work (Kendler, 1996) has found higher rates of reported concordance in parental behavior towards members of both identical and fraternal twin pairs, resulting in decreased estimates for genetic and unique environmental effects and increased estimates for shared environment when compared to estimates based on twin report. Nonetheless, the substantial support for the reliability and predictive utility of adolescent reports on the parent-child relationship (Metzler, Biglan, Ary, & Li, 1998; Elkins et al. 1997; Burt et al. 2005) demonstrate the utility of such measures.

Second, the present study relied on child reports. If children become increasingly accurate reporters as they age, we would expect estimates of the E parameter, which includes both non-shared environmental effects and measurement error, to decrease with age. However, we did not observe decreases in E, and the two primary features of interest in the growth curve results – the negative covariance of slope and intercept for environmental components and the positive covariance of slope and intercept for genetic factors – suggest that the increase in estimated heritability was not due to a simple improvement in measurement.

Third, when interpreting the observed heritability increase it is also important to consider the finding in the context of theorized developmental changes in the nature of gene-environment correlation (rGE) processes during this time period. Early correlations between genotype and environment are generally due to the actions of parents, who actively shape their children’s environments throughout the early years. As children age, their environments are increasingly shaped both by responses to their behavior from people outside the home and eventually by the kinds of environments the children create or select for themselves (Scarr & McCartney, 1983), thus shifting from correlation between A and C to correlation between A and E. Purcell (2002) noted that the presence of any correlation between genes and shared environment will produce inflated estimates of C, while correlation between genes and non-shared environment will produce inflated estimates of A. Thus, an age-related decline in estimates for the importance of shared environmental factors and increasing importance of genetic influences is expected for any phenotypes which exhibit declining “passive” and increasing “active” or “evocative” rGE processes with age. In the context of the marked increases in total variance for the parent-child relationship across adolescence, however, we believe that the observed biometric trends likely represent more than an artifactual shift of this nature.

Fourth, with only three data points growth curve models have limited power to resolve linear from non-linear growth trajectories. Future work should seek to ascertain the forms of these parental relationship trajectories more precisely by including a larger number of time points.

Finally, while the sample is representative of the Minnesotan population during the period in which the sample was born, it is more ethnically homogeneous than the U.S. population (see Iacono et al., 1999; Iacono & McGue, 2002). Several studies (e.g. Turkheimer et al., 2003; Legrand et al., 2008) have illustrated the need for caution in generalizing results from behavioral genetic studies into populations meaningfully different than that represented in the study.

With those limitations in mind, we believe the results presented here provide an intriguing window into the nature of the relationship between parents and their children. Our growth curve model showed that the increasing importance of additive genetic influences between ages 11 and 14, identified previously by McGue et al. (2005), was part of a continuing trend that showed further increases in genetic influences between 14 and 17. This took place in the context of generally deteriorating parental relationships and increasing overall variance in those relationships. This suggests that in the earlier years some of the quality of parental relationships may be maintained by the control parents are able to exert (and which the children essentially must accept) over their children’s experiences and behavior. As children grow, however, they have more choice over their experiences and can more freely express their own reactions to the choices their parents have made for them, some accepting them readily and others less so. These two patterns may be related: if the parent-child relationship proceeds more smoothly when children are more accepting of the terms of that relationship offered by the parent, then we should expect that periods of high parental influence over the characteristic (indicated by high values for shared environmental influence) would be characterized by relatively positive relationships between parent and child. To the extent that the child’s efforts to bring the relationship in line with his or her individual dispositions are resisted by the parent, an increased role for genetic influence on this relationship should be accompanied by greater levels of discord. As parents may differ in how easily they accommodate such efforts, future research should explore whether parents whose opinions on child rearing indicate greater resistance to such an accommodation witness a particularly steep decline in their relationship with their child throughout adolescence as a result of the increasing individualization identified in the present study.

With the growth-curve model we also identified important trends behind the observed increase in heritability. While variance due to additive genetic sources increased almost universally for both sexes at both intervals, variance due to shared environmental factors decreased markedly between ages 14 and 17. Further, though variance due to non-shared environmental factors increased, it did so at a modest pace compared to additive genetic factors, leading to a decline in its importance when standardized. Of particular interest is that these trends were not the result of small environmental contributions to slope. Indeed, the contributions to slope were higher for environmental than for genetic factors. However, both shared and non-shared environmental factors had negative correlations between slope and intercept. This stands in contrast to additive genetic factors, for which the slope and intercept were positively correlated. We interpret these results as an indication that genetic effects amplified in importance throughout development (Plomin, 1986).

The findings of increased heritability throughout development in this particular phenotype are consistent with two important and growing bodies of literature within behavioral genetics. The first of these was summarized by Kendler and Baker (2007), who reviewed findings of genetic influence on environmental variables such as exposure to stressful life events (Kendler et al., 1993), peer interactions (Walden et al., 2004), and the family environment (Elkins et al., 1997). Genetic effects of small to moderate size are consistently demonstrated for a wide range of purportedly environmental variables in this literature.

The present work also contributes to another more thoroughly explored vein of research, summarized by Bergen et al. (2007), which notes the increases in heritability during development found across all domains examined to date. These include previous cross-sectional (Elkins et al., 1997) and longitudinal (McGue et al., 2005) work on this particular phenotype, as well as a host of other psychological features such as IQ (McGue, Bouchard, Iacono, & Lykken, 1993; Plomin, Fulker, Corley, & DeFries, 1997), social and political attitudes (Eaves et al., 1997), personality (McGue, Bacon, & Lykken, 1993), and religiousness (Koenig, McGue, Krueger, & Bouchard, 2005).

Both of these research areas derive from long-standing conceptions of how genes and environments come to correlate over time periods during development – in particular, the above-noted concept of gene-environment correlation (Scarr and McCartney, 1983), in which the correlation between genotype and environment across development is increasingly a function of the expression of each person’s own genotype. As many of the psychological features which are conventionally pictured as affecting or creating an individual’s environment – an individual’s level of agreeableness, extraversion, or antisociality – are known to be significantly subject to genetic influence, genetic influence on environmental variables such as those examined here is not unexpected. Similarly, the increasing contribution of genetic factors to environmental variables as individuals age is expected under this framework, as genetic contributions to individuals’ personalities and preferences become increasingly relevant as they become more able to influence their environments. The mechanism demonstrated by the growth curve model to be responsible for this process – the amplification of any initial differences due to genetic influences as children age – has a comparably sound theoretical footing (cf. Plomin, 1986), but to our knowledge the present study is the most direct demonstration of this process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by U. S. Public Health Service Grants AA09367 and DA05147. The authors greatly appreciate the assistance of MCTFR staff in this work and especially that of Dr. Greg Perlman.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Information Theory. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The Influence of Parenting Style on Adolescent Competence and Substance Use. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1991;11(1):56–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen SE, Gardner CO, Kendler KS. Age-related changes in heritability of behavioral phenotypes over adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10(3):423–33. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, McGue M, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. How are parent-child conflict and childhood externalizing symptoms related over time? Results from a genetically informative cross-lagged study. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17(1):145–65. doi: 10.1017/S095457940505008X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG. Genetic and environmental influences on parent-son relationships: evidence for increasing genetic influence during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(2):351–63. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmborg JVB, Fagnani C, Silventoinen K, McGue M, Korkeila M, Christensen K, Rissanen A, Kaprio J. Genetic influences on growth traits of BMI: a longitudinal study of adult twins. Obesity. 2008;16(4):847–52. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Edwards LA. Parental attitudes toward child rearing: Instruments, issues, and implications. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106(1):29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11(4):869–900. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono WG, McGue M. Minnesota Twin Family Study. Twin Research. 2002;5(5):482–487. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Krueger RF, Bouchard TJ, McGue M. The personalities of twins: just ordinary folks. Twin Research. 2002;5(2):125–131. doi: 10.1375/1369052022992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Silbereisen RK. Supportive parenting and adolescent adjustment across time in former East and West Germany. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22(6):719–36. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K. Parenting: A genetic-epidemiologic perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153(1):11–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS. Twin studies of psychiatric illness: an update. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(11):1005–14. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.11.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Baker JH. Genetic influences on measures of the environment: a systematic review. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37(5):615–26. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Prescott CA, Neale MC. The genetic epidemiology of irrational fears and phobias in men. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(3):257–65. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KJ, Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Elder GH., Jr Parent-adolescent reciprocity in negative affect and its relation to early adult social development. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(6):775–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrand LN, Keyes M, McGue M, Iacono WG, Krueger RF. Rural environments reduce the genetic influence on adolescent substance use and rule-breaking behavior. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(9):1341–1350. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Drinkwater M, Yin Y, Anderson SJ, Schmidt LC, Crawford A. Stability of family interaction from ages 6 to 18. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:353–369. doi: 10.1023/a:1005169026208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF. An empirical comparison of information-theoretic selection criteria for multivariate behavior genetic models. Behavior Genetics. 2004;34(6):593–610. doi: 10.1007/s10519-004-5587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Elkins I, Walden B, Iacono WG. Perceptions of the parent-adolescent relationship: a longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41(6):971–84. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.6.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzler CW, Biglan A, Ary DV, Li F. The stability and validity of early adolescents’ reports of parenting constructs. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(4):600–619. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: Statistical Modeling. 6. Richmond, VA: Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Cardon LR. Methodology for genetic studies of twins and families. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, McArdle JJ. Structured latent growth curves for twin data. Twin Research. 2000;3(3):165–177. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike A, McGuire S, Hetherington EM, Reiss D, Plomin R. Family environment and adolescent depressive symptoms and antisocial behavior: A multivariate genetic analysis. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32(4):590–604. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R. Development, genetics, and psychology. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Plomin R, DeFries JC, McClearn GE, Rutter M. Behavioral genetics: A primer. 3. San Francisco: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. Variance components models for gene-environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Research. 2002;5(6):554–71. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss D, Neiderhiser JM, Hetherington EM, Plomin R. The relationship code: Deciphering genetic and social influences on adolescent development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: a meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin. 1994;116(1):55–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC. Environmental and genetic influences on dimensions of perceived parenting: A twin study. Developmental Psychology. 1981;17(2):203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC. A biometrical analysis of perceptions of family environment: A study of twin and singleton sibling kinships. Child Development. 1983;54(2):416–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarr S, McCartney K. How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype environment effects. Child Development. 1983;54(2):424–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1983.tb03884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman II. Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychological Science. 2003;14(6):623–628. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden B, McGue M, Lacono WG, Burt SA, Elkins I. Identifying shared environmental contributions to early substance use: the respective roles of peers and parents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113(3):440–450. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.3.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]