Abstract

Background and Purpose

Hyperintense vessels (HV) have been observed in Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) imaging of patients with acute ischemic stroke and been linked to slow flow in collateral arterial circulation. Given the potential importance of HV, we used a large, multicentre dataset of stroke patients to clarify which clinical and imaging factors play a role in HV.

Methods

We analyzed data of 516 patients from the previously published PRE-FLAIR study. Patients were studied by MRI within 12 hours of symptom onset. HV were defined as hyperintensities in FLAIR corresponding to the typical course of a blood vessel that was not considered the proximal, occluded main artery ipsilateral to the diffusion restriction. Presence of HV was rated by two observers and related to clinical and imaging findings.

Results

Presence of HV was identified in 240 of all 516 patients (47%). Patients with HV showed larger initial ischemic lesion volumes (median 12.3 vs. 4.9 ml; p<0.001) and a more severe clinical impairment (median NIHSS 10.5 vs. 6; p<0.001). In 198 patients with MR-angiography, HV were found in 80% of patients with vessel occlusion and in 17% without vessel occlusion. In a multivariable logistic regression model, vessel occlusion was associated with HV (OR 21.7%; 95% CI 9.6–49.9, p < 0.001). HV detected vessel occlusion with a specificity of 0.86 (95% CI 0.80–0.90) and sensitivity of 0.76 (95% CI 0.69–0.83).

Conclusions

HV are a common finding associated with proximal arterial occlusions and more severe strokes. HV predict arterial occlusion with high diagnostic accuracy.

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, diffusion-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery stroke, acute

Introduction

In MR-imaging of acute ischemic stroke patients, use of Fluid-attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) sequences has recently gained importance as a tool to assess lesion age.1 A separate finding on FLAIR-images has been termed “hyperintense vessels” (HV) and describes hyperintensities corresponding to an arterial course most conspicuous in the sylvian fissure and cortical sulci2–4. Most likely, HV result from retrograde flow via collateral arterial circulation, as has been shown by concurrent angiographic examinations2–4. Pathophysiologically, sluggish blood flow is thought to result in an absence of flow void in these arteries causing increased signal intensities. We investigated, whether clinical and imaging characteristics would support this hypothesis in a representative, large and multicentre group of acute stroke patients.

Methods

MR- and clinical data from patients included for final analysis in the previously published PRE-FLAIR study (PREdictive value of FLAIR and DWI for the identification of acute ischemic stroke patients ≤ 3 and ≤ 4.5 h of symptom onset – a multicenter study) were reviewed according to the presence of HV1. In this multicentre observational study, we analysed clinical and MRI data from patients with acute stroke studied by MRI including DWI and FLAIR within 12 h of observed symptom onset. The study was performed by an international consortium of researchers within the Stroke Imaging Repository (STIR) and Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive (VISTA) Imaging research groups. PRE-FLAIR included individual datasets from seven participating stroke centres and three studies: EPITHET (Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolysis Evaluation Trial), which was a phase 3 prospective, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multinational trial,5 VIRAGE (Valeur predictive des parametres IRM à la phase aigue de l’accidentvasculaire cerebral: application à la gestion des essaisthérapeutiques), which was a national multicentre study,6 and the 1000Plus study, a prospective study on the mismatch concept in acute stroke patients within the first 24 h after symptom onset.7 Patients presented during different time periods between Jan 1, 2001, and May 31, 2009. Patients were enrolled if they had well defined symptom onset (ie, exact time of symptom onset was recorded and reported by either the patient or somebody who witnessed their symptom onset.) Details of imaging parameters and postprocessing have been reported1. Patients received no contrast agents prior to imaging with FLAIR-sequences. All patients were studied within 12 hours of stroke onset. Patient age, time from symptom onset to MRI, severity of neurological deficit on admission (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)) and stroke cause (according to Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST)8) were recorded1. Visibility of FLAIR-lesions corresponding to DWI-lesions was rated as described previously1. Additionally, one observer (BC) assessed the affected vascular territory and pattern of ischemic lesions on DWI images regarding the assumed aetiology (territorial, lacunar, hemodynamic and multiple embolic distribution). HV were defined as hyperintensities in FLAIR corresponding to the typical course of a blood vessel that was not considered the proximal, occluded main artery ipsilateral to the diffusion restriction (see Figure 1). Presence of HV was rated by two observers (BC and ME) and consensus reached in cases of disagreement. Both observers were independent from each other and blinded to clinical information and blinded to results from MR-angiography. Kappa-values were used to determine inter-rater agreement. Information on vessel occlusion from time-of-flight MR angiography was available from two centres (Hamburg, Berlin) and one imaging database (VIRAGE, Valeurprédictive des paramètres IRM a la phase aigüe de l’accident vasculairecérébral: application à la gestion des essaisthérapeutiques) 6, 7, 9. Group comparison depending on the presence or absence of HV was performed using Mann-Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. In the subgroup of patients with data on vessel occlusion, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed with presence of HV as dependent variable (enter model) including the variables “time from symptom onset”, “DWI lesion volume”, “NIHSS score” and “vessel occlusion (yes or no)”. All statistical analysis was performed using commercial statistical software (SPSS 19.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

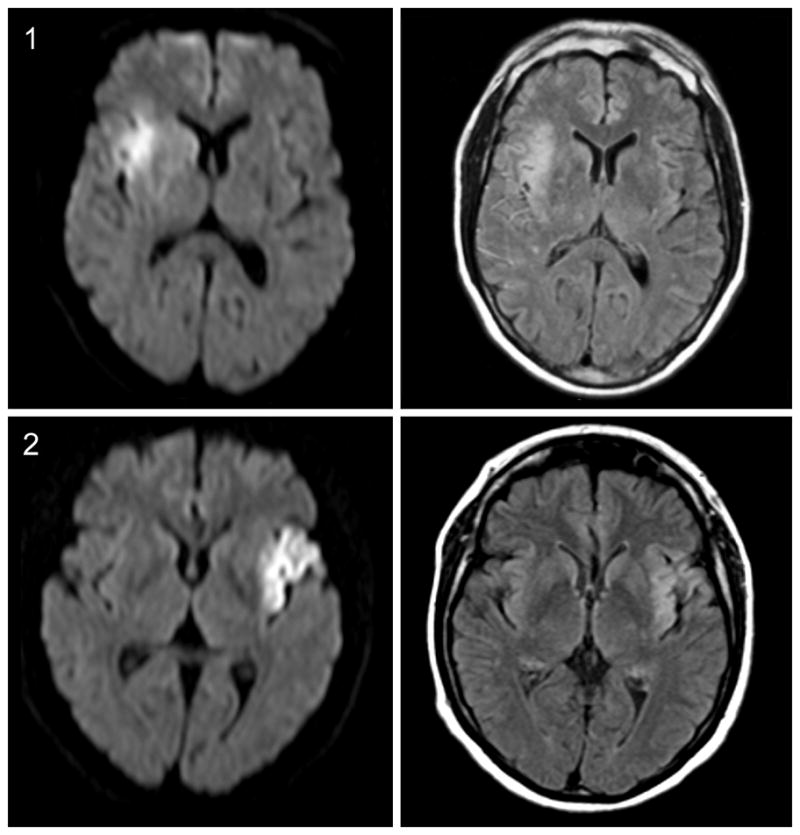

Figure 1.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI, left) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR, right) sequences of two acute stroke patients. FLAIR hyperintensities in arteries (1) and no FLAIR hyperintensities in arteries (2)

Results

FLAIR-images of 516 Patients were included in the analysis (table 1). Presence of HV was observed in 240 Patients (46.5%). Inter-rater agreement for the detection of HV was 94% with a κ of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.89–0.97). In group comparison, patients with HV had larger DWI lesion volumes (geometric mean 11.9 vs. 4.9 ml; p<0.001) and were more severely impaired (median NIHSS score 12.3 vs. 4.9; p<0.001) as compared to patients without HV (table 1). Data for stroke aetiology classified by TOAST were available from 428 (82.9%) of all patients, and significant differences were detected with small-vessel occlusion being less frequently the cause of stroke in patients with HV (1% vs. 8.9%; p=0.001). HV were more frequently associated with territorial strokes in the middle cerebral artery territory as compared to lacunar lesions or infarctions in the territory of the posterior or anterior cerebral artery. Patients with HV and those without were comparable with regards to time from symptom onset and the presence of visible parenchymal hyperintensities on FLAIR.

Table 1.

Group comparison HV negative vs. HV positive

| No HV (n=276) | HV (n=240) | Group comparison, P- Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [y] | 66.0 (64.2–67.7) | 65.7 (63.6–67.7) | 0.814 |

| NIHSS score on admission*† | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (8) | 10.5 (12) | |

| Arithmetic mean (95% CI) | 8.2 (7.4–9) | 12.1 (11.1–13) | |

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 7.1 (6.5–7.8) | 10.6 (9.6–11.6) | < 0.001 |

| Time to MRI [min] * | 204.9 (188.1–222.2) | 189.5 (174.5–208.5) | 0.154 |

| Parenchymal hyperintensities on FLAIR‡ | 152 (55.1%) | 121 (50.4%) | 0.291 |

| DWI lesion Volume [ml]* | |||

| Median (IQR) | 4.9 (17.7) | 12.3 (33.2) | |

| Arithmetic mean | 19.9 (15.6–24.3) | 28.4 (23.6–33.2) | |

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 4.9 (3.9–6.1) | 11.9 (9.8–14.2) | < 0.001 |

| Type§ | < 0.001 | ||

| Territorial infarcts | 169 (61.2%) | 210 (87.5%) | |

| Lacunar infarcts | 77 (27.9%) | 13 (5.4%) | |

| Hemodynamic infarcts | 10 (3.6%) | 0 | |

| Multiple embolic infarcts | 20 (7.2%) | 17 (7.1%) | |

| Localization§ | < 0.001 | ||

| Brainstem | 3 (1.1%) | 0 | |

| Cerebellum | 13 (4.7%) | 0 | |

| Posterior cerebral artery | 15 (5.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Middle cerebral artery | 231 (83.7%) | 238 (99.2%) | |

| Anterior cerebral artery | 7 (2.5%) | 0 | |

| Multiple locations | 7 (2.5%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Cause| | | < 0.001 | ||

| Large-artery atherosclerosis | 78/224 (34.8%) | 67/204 (32.8%) | |

| Cardioembolism | 71/224 (31.7%) | 84/204 (41.2%) | |

| Small-vessel occlusion | 20/224 (8.9%) | 2/204 (1.0%) | |

| Other determined | 17/224 (7.6%) | 23/204 (11.3%) | |

| Undetermined | 38/224 (17.0%) | 28/204 (13.7%) | |

| Vessel status/occlusion | < 0.001 | ||

| No occlusion | 97/117 (82.9%) | 16/81 (19.8%) | |

| ICA | 4/117 (3.4%) | 9/81 (11.1%) | |

| Carotid T | 0 | 4/81 (4.9%) | |

| MCA M1 segment | 8/117 (6.8%) | 36/81 (44.4%) | |

| MCA M2 segment | 8/117 (6.8%) | 16/81 (19.8%) | |

Values are given as mean (95% CI) or count (percentage) as appropriate. Group comparison was performed using student’s t-Test or Fisher’s exact test

Due to asymmetric distribution logarithmic transformation was applied before group comparison and geometric mean (95% CI) is given in addition to median (IQR) and arithmetic mean (95% CI)

Data missing for 5 patients (included)

FLAIR-lesion corresponding to acute DWI-lesion (“FLAIR-positive”) as rated previously1

categorized by visual rating of acute DWI-lesion according to anatomical localization, lesion pattern and vascular territory

Classification according to TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) definitions

NIHSS indicates National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery

MRI-angiography was available for 198 of 516 patients (38.4%). Vessel occlusion was found more frequently in patients with HV (80.2 %) as compared to patients without HV (17.1%). In the multivariable logistic regression model, only vessel occlusion was significantly associated with HV (p < 0.001; Odds ratio 21.7; 95% CI 9.6–49.9), whereas NIHSS score, time from symptom onset and acute DWI lesion volume were not (table 2). In this subgroup of patients, presence of HV predicted vessel occlusion as demonstrated by MR-angiography with high specificity (0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.90) and sensitivity (0.76, 95% CI 0.69–0.83). The positive predictive value was 0.80 (95% CI 0.72–0.87), negative predictive value 0.83 (0.77–0.87). Overall diagnostic accuracy was 0.82 (95% CI 0.75–0.87).

Table 2.

Predictors for the presence of HV

| Predictors | OR (95 % CI) Multivariate | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Vessel occlusion (ICA or MCA) | 21.682 (9.591–49.013) | < 0.0001 |

| DWI lesion volume [ml] | 0.986 (0.973–1.0) | 0.053 |

| NIHSS | 1.056 (0.987–1.130) | 0.113 |

| Time to MRI [min] | 1.0 (0.998–1.002) | 0.782 |

Results of multivariate binary regression analysis, parameters sorted by p-values in ascending order; data for 198 patients; HV indicates hyperintense vessels; OR, Odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICA, internal cerebral artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; DWI, diffusion weighted imaging; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Discussion

Hyperintense vessels are a frequent observation in acute stroke. However, the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon and clinical implications of HV have been a matter of debate. Previously, correlative angiographic studies demonstrated that HV most likely reflect slow arterial blood flow in leptomeningeal collateral circulation 4, 10 resulting in a loss of “flow void” and increased signal in FLAIR sequences. This hypothesis has been corroborated by several observations reporting the presence of HV with large vessel stenosis or occlusion11, showing a transient nature of HV and their absence in the hemisphere contralateral to cerebral ischemia4. We aimed to clarify whether or not clinical and imaging findings from a large, typical acute stroke population would be in line with this hypothesis.

Presence of HV was observed in almost half of our patients. As a main finding, HV occurred as a function of proximal vessel occlusion. HV were associated with larger ischemic lesion volumes and higher NIHSS scores. Large lesion volume and clinically severe strokes are both related to the presence and location of large vessel occlusion. Unlike parenchymal hyperintensities in FLAIR, HV were not related to time from symptom onset. HV have been observed in areas supplied by collateral blood flow over weeks12, but a clear time dependency of their presence has not been demonstrated yet.

To further elucidate the clinical implications of HV we characterized stroke aetiology indirectly by visually assessing images from DWI in terms of ischemic lesion pattern and distribution. HV were mainly present in territorial lesions occurring in the arterial territory of the MCA (table 1). HV were observed significantly less frequent in patients with lacunar infarctions, a finding that is most likely explained by the small size of the occluded vessel representing end arteries without appreciable collateral circulation.

Information on vessel status assessed by MR-angiography was available in a subgroup of patients. Congruently to visual lesion pattern characterization, presence of HV corresponded to proximal vessel occlusion, particularly affecting the M1-segment of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) as reported previously13, 14. HV predicted vessel occlusion with high diagnostic accuracy. This finding supports results from previous studies analyzing the diagnostic value of HV regarding the detection of proximal large vessel occlusion14, 15. However, as we had no data on conventional angiography, we cannot prove a causal link between collaterals and HV. The association of HV with DWI lesion volume and severity of symptoms is in line with previous studies of acute stroke patients in which correlations between the extent of HV and initial lesion size as well as clinical condition have been observed 3, 13. Nonetheless, Lee et. al. found smaller ischemic lesion volumes and milder clinical severity in association with HV16 occurring distally in relation to the site of MCA occlusion. In turn, a more recent study showed an association between HV and worse functional outcome three months after stroke17. Clinical or functional outcome were not available for all contributing studies. Future studies should address the question whether the presence of HV is related to both tissue outcome and clinical outcome.

To our knowledge, our study represents the largest group of acute stroke patients studied with regard to the presence of HV so far. Although imaging parameters and quality of scans differed significantly between examinations, agreement for the detection of HV was almost perfect between the two raters. Our observations are of additional value to previous studies, where smaller groups of patients examined at various time points2 have been studied thus limiting direct comparability.

In conclusion, imaging and clinical findings in a large population of patients with acute ischemic strokes are consistent with the hypothesis that HV represent arterial collateral flow in patients with proximal large vessel occlusion. Further studies are needed to investigate the full clinical impact of HV in stroke.

Acknowledgments

STroke Image Repository (STIR) and Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive (VISTA) Imaging steering committee: Steven Warach (chair), Gregory Albers, Stephen Davis, Geoff Donnan, Marc Fisher, Tony Furlan, James Grotta, Werner Hacke, Dong-Wa Kang, Chelsea Kidwell, Kennedy R. Lees, Micheal Lev, David Liebeskind, Vincent Thijs, Götz Thomalla, Joanna Wardlaw, Max Wintermark.

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

The PREdictive value of FLAIR and DWI for the identification of acute ischemic stroke patients ≤ 3 and ≤ 4.5 h of symptom onset – a multicenter study (PRE-FLAIR) has received funding from the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2009_A36).

In Berlin data were collected within the 1000+ study, which has received funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research via the grant Center for Stroke Research Berlin (01 EO 0801). This work was further supported by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme grant agreement No 202213 and No 223153 (European Stroke Network), the Volkswagen Foundation and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Echoplanar Imaging Thrombolysis Evaluation Trial (EPITHET) was a phase II prospective, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multinational trial funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia), the National Stroke Foundation (Australia), and the Heart Foundation of Australia. Valeur predictive des parametres IRM à la phase aigue de l’accidentvasculaire cerebral: application à la gestion des essaisthérapeutiques (VIRAGE) is a national multicentre study supported by French national grant “Le programme hospitalier de recherche Clinique” (PHRC).

Footnotes

Disclosures

Jochen B. Fiebach has received fees as a board member, consultant, or lecturer from BoehringerIngelheim, Lundbeck, Siemens, Syngis, and Synarc.

Christian Gerloff has received fees as a consultant or lecture fees from Bayer Vital, BoehringerIngelheim, EBS technologies, Glaxo Smith Kline, Lundbeck, Pfizer, Sanofi Aventis, Silk Road Medical, and UCB.

David S. Liebeskind has received fees as a consultant for CoAxia and Concentric Medical, Inc.

Götz Thomalla has received a research grant from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung.

Thomas Tourdias has received a national grant from the French Government (PHRC).

Ona Wu was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS059775, R01NS063925, P50NS051343) and received royalties and licensing fees from GE, Olea and Imaging Biometrics.

Bastian Cheng, Soren Christensen, Martin Ebinger, Anna Kufner, Dong-Wha Kang, MartinKoehrmann, Oliver Singer, Marie Luby and Steven Warach have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Bastian Cheng, Email: b.cheng@uke.uni-hamburg.de.

Martin Ebinger, Email: martin.ebinger@charite.de.

Anna Kufner, Email: anna.kufner@charite.de.

Martin Köhrmann, Email: Martin.Koehrmann@uk-erlangen.de.

Ona Wu, Email: ona@nmr.mgh.harvard.edu.

Dong-Wha Kang, Email: dwkang@amc.seoul.kr.

David Liebeskind, Email: davidliebeskind@yahoo.com.

Thomas Tourdias, Email: thomas.tourdias@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Oliver C. Singer, Email: O.Singer@em.uni-frankfurt.de.

Soren Christensen, Email: sorench@gmail.com.

Steve Warach, Email: WarachS@ninds.nih.gov.

Marie Luby, Email: LubyM@ninds.nih.gov.

Jochen B. Fiebach, Email: jochen.fiebach@charite.de.

Jens Fiehler, Email: fiehler@uke.de.

Christian Gerloff, Email: gerloff@uke.de.

Götz Thomalla, Email: thomalla@uke.uni-hamburg.de.

References

- 1.Thomalla G, Cheng B, Ebinger M, Hao Q, Tourdias T, Wu O, et al. Dwi-flair mismatch for the identification of patients with acute ischaemic stroke within 4.5 h of symptom onset (pre-flair): A multicentre observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;10:978–986. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizyan A, Sanossian N, Mogensen MA, Liebeskind DS. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery vascular hyperintensities: An important imaging marker for cerebrovascular disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:1771–1775. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamran S, Bates V, Bakshi R, Wright P, Kinkel W, Miletich R. Significance of hyperintense vessels on flair mri in acute stroke. Neurology. 2000;55:265–269. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanossian N, Saver JL, Alger JR, Kim D, Duckwiler GR, Jahan R, et al. Angiography reveals that fluid-attenuated inversion recovery vascular hyperintensities are due to slow flow, not thrombus. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:564–568. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis SM, Donnan GA, Parsons MW, Levi C, Butcher KS, Peeters A, et al. Effects of alteplase beyond 3 h after stroke in the echoplanar imaging thrombolytic evaluation trial (epithet): A placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:299–309. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tourdias T, Dousset V, Sibon I, Pele E, Menegon P, Asselineau J, et al. Magnetization transfer imaging shows tissue abnormalities in the reversible penumbra. Stroke. 2007;38:3165–3171. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.483925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hotter B, Pittl S, Ebinger M, Oepen G, Jegzentis K, Kudo K, et al. Prospective study on the mismatch concept in acute stroke patients within the first 24 h after symptom onset - 1000plus study. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Toast. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiehler J, Knudsen K, Thomalla G, Goebell E, Rosenkranz M, Weiller C, et al. Vascular occlusion sites determine differences in lesion growth from early apparent diffusion coefficient lesion to final infarct. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1056–1061. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu W, Xu G, Yue X, Wang X, Ma M, Zhang R, et al. Hyperintense vessels on flair: A useful non-invasive method for assessing intracerebral collaterals. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:786–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iancu-Gontard D, Oppenheim C, Touze E, Meary E, Zuber M, Mas JL, et al. Evaluation of hyperintense vessels on flair mri for the diagnosis of multiple intracerebral arterial stenoses. Stroke. 2003;34:1886–1891. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000080382.61984.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Essig M, von Kummer R, Egelhof T, Winter R, Sartor K. Vascular mr contrast enhancement in cerebrovascular disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:887–894. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schellinger PD, Chalela JA, Kang DW, Latour LL, Warach S. Diagnostic and prognostic value of early mr imaging vessel signs in hyperacute stroke patients imaged <3 hours and treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:618–624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cosnard G, Duprez T, Grandin C, Smith AM, Munier T, Peeters A. Fast flair sequence for detecting major vascular abnormalities during the hyperacute phase of stroke: A comparison with mr angiography. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:342–346. doi: 10.1007/s002340050761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toyoda K, Ida M, Fukuda K. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery intraarterial signal: An early sign of hyperacute cerebral ischemia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1021–1029. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KY, Latour LL, Luby M, Hsia AW, Merino JG, Warach S. Distal hyperintense vessels on flair: An mri marker for collateral circulation in acute stroke? Neurology. 2009;72:1134–1139. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345360.80382.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebinger M, Kufner A, Galinovic I, Brunecker P, Malzahn U, Nolte CH, et al. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images and stroke outcome after thrombolysis. Stroke. 2011;43:539–542. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.632026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]