Abstract

Omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids have been implicated in mood disorders, yet clinical trials supplementing n-3 fats have shown mixed results. However, the predominant focus of this research has been on the n-3 fatty acids docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). We used an unbiased approach to assay plasma n-3 and omega-6 (n-6) species that interact at the level of biosynthesis and down-stream processing, to affect brain function and, potentially, mood. We used lipomic technology to assay plasma levels of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids from 40 bipolar and 18 control subjects to investigate differences in plasma levels and associations with the burden of disease markers, neuroticism and global assessment of function (GAF) and mood state (Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)). Most significantly, we found the levels of dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA) to positively correlate with neuroticism and HAM-D scores and negatively correlate with GAF scores; and HAM-D to negatively correlate with linoleic acid (LA) and positively correlate with fatty acid desaturase 2 (FADS2) activity, an enzyme responsible for converting LA to gamma-linolenic acid (GLA). These associations remained significant following Bonferroni multiple testing correction. These data suggest that specific n-6 fatty acids and the enzymes that control their biosynthesis may be useful biomarkers in measurements of depressive disorders and burden of disease, and that they should be considered when investigating the roles of n-3s.

Keywords: omega-3 fatty acids, omega-6 fatty acids, dihomogamma linolenic acid, fatty acid desaturase, neuroticism, global assessment of function

BACKGROUND

Bipolar Illness strikes approximately 5.7 million adults in the United States, or about 1–2% of the adult population in any given year (Kessler et al., 2005) and is a chronic illness requiring long-term management. Although estimates are difficult to establish, it is likely that more than 50% of bipolar subjects who seek medical treatment continue to struggle with life disrupting episodes (Thase, 2007). Psychiatrists have a limited toolkit to treat bipolar illness, focusing on antidepressant, mood stabilizing and antipsychotic drugs and various cognitive therapies to regulate depressive and manic episodes. While these approaches have benefit for some, additional adjunct therapies are desired.

Dietary approaches are part of the therapeutic toolbox to manage several chronic illnesses, including those that have a high rate of co-morbidity with bipolar illness such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the metabolic syndrome (Newcomer, 2006). However, the efficacy of dietary approaches as adjunct therapies in managing psychiatric illness is understudied. One component of the diet that may be relevant to psychiatric illnesses are the polyunsaturated fatty acids in the n-3 and n-6 classes.

Evidence for the involvement of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in depression and bipolar disorder comes from several related lines of investigation. First, epidemiological studies have pointed to an association between n-3 and n-6 dietary intake and lifetime prevalence of depression and bipolar disorder. Populations that consume greater long-chain n-3s and less long chain n-6s have a lower incidence of unipolar and bipolar depression (Hibbeln, Nieminen, Blasbalg, Riggs, & Lands, 2006). Second, animal studies have shown that diets deficient in n-3s alter monoamine systems in limbic structures known to control mood (reviewed by Chalon (Chalon, 2006)). Third, mood stabilizers commonly used to treat bipolar disorder specifically inhibit membrane turnover and downstream signaling of the n-6, arachidonic acid (AA), but not the n-3, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, (Rapoport, Basselin, Kim, & Rao, 2009)). Both lithium and carbamazepine decrease expression of phospholipase A2, responsible for cleaving the AA from the membrane. Additionally, lithium, carbamazepine, valproate and lamotrigine inhibit COX2 expression, responsible for processing AA into the prostaglandin E2 series signaling molecules. These data suggest that mood stabilizers may tip the scales in the direction of long chain n-3 activity, by inhibiting AA function and reducing competition with DHA and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). Furthermore anti-depressants that increase AA activity in rodents (e.g. imipramine), have a higher probability of inducing mania in human bipolar subjects (Lee, Rao, Chang, Rapoport, & Kim, 2009).

While the mechanism linking these results to mood regulation is not well understood, there are several possibilities including the influence of the AA:DHA ratio on membrane fluidity and receptor kinetics (Gawrisch, Soubias, & Mihailescu, 2008); the processing of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids to competing prostaglandins and leukotrienes that have a paracrine effect on local cells and have been implicated in control of sleep (Urade & Hayaishi, 2011), stress response (Furuyashiki & Narumiya, 2011) and suicidality (Schumock et al., 2011); and the production of endocannabinoids from AA that can influence the excitability of local circuits, including serotonin systems (Haj-Dahmane & Shen, 2011).

By extension, these data provide impetus to study diet and blood markers of diet in the control of affective disorders. The data are consistent with the hypothesis that low long chain n-3 or high long chain n-6 tissue concentration, due to gene-diet interactions (discussed below), may destabilize mood and suggest that the tissue balance between competing n-3 and n-6 fatty acid species may play a role in the pathoetiology of depressive disorders.

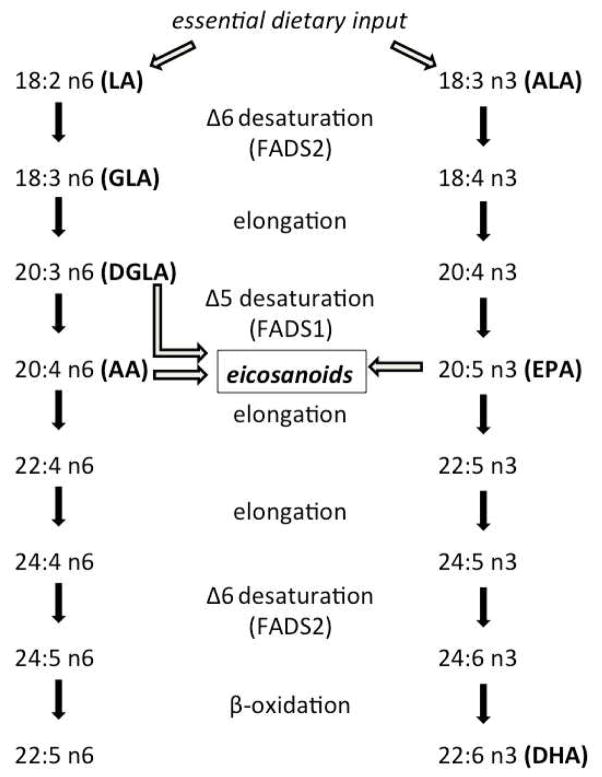

The n-3 and n-6 PUFA are essential in the diet, since they cannot be synthesized de novo by mammals. Technically, we only need to obtain the n-3, alpha linolenic acid (ALA), and the n-6, linoleic acid (LA), from dietary sources to synthesize longer chain n-3 and n-6 lipids from those (Figure 1). However, studies have shown that humans may be inefficient at converting short to long chain fatty acids and thus the tissue composition of all n-3 and n-6 lipids partially reflects dietary consumption (Arterburn, Hall, & Oken, 2006). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in fatty acid desaturase (FADS) genes, partially responsible for metabolic inter-conversion, influence n-3 and n-6 blood levels as well (Glaser, Heinrich, & Koletzko, 2010), defining a gene-diet interaction in the control of PUFA profiles. Furthermore, mRNA expression of the FADS1 and FADS2 genes are relatively high in brain tissues and thus, their allelic variants may be important factors related to neurochemistry and psychiatric illness. In fact, FADS1 and FADS2 expression have been found to be altered in the prefrontal cortex of bipolar and depressed subjects (Liu & McNamara, 2011; McNamara & Liu, 2011).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the desaturation and elongation biosynthetic pathway of essential dietary fatty acids to longer chain fats. Precursors of the eicosanoid class of signaling molecules are also highlighted. n-6 acronyms: LA, linoleic acid; GLA, gamma-linolenic acid; DGLA, dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid; AA, arachidonic acid. n-3 acronyms: ALA, alpha-linolenic acid, EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid. Enzyme acronyms: FADS1, fatty acid desaturase 1; FADS2 fatty acid desaturase 2.

Supplementation with the long-chain n-3 (n-3) fatty acids, DHA and EPA, either as stand alone or adjunctive therapies have shown efficacy in the treatment of depression. However, results across studies are inconsistent and the clinical efficacy of n-3s as a therapeutic tool for depressive illness is unclear. A 2008 review by Turnbull et al. surveyed clinical trials that used n-3s to treat bipolar disorder (Turnbull, Cullen-Drill, & Smaldone, 2008). From over 100 publications, seven high quality and well-controlled trials were identified, of which four found positive mood improvements, two found no mood improvements and one did not report on mood improvements following n-3 supplementation. Therefore, while data is promising there remains ambiguity in the field. However, one factor not considered in supplementation trials to date is the concentration of n-6 fatty acids, which play complex physiological roles in health benefit, anti- and pro-inflammatory states, and are known to compete with each other and with n-3 fatty acids in many cellular processes. To fully understand the efficacy of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in bipolar depressive illness we will need an understanding of the subjects’ complete lipid profiles and the ratios between competing lipids and their possible influence on various burdens of disease.

We previously reported that higher plasma ratios of EPA relative to its precursor, ALA, or its product, DHA associated with increased agreeableness and extraversion (Evans et al., 2012). Several other studies suggest that low serum n-3 PUFA associates with aggressive and violent behavior. For example, n-3 PUFA have been found to be lower in suicide attempters (Huan et al., 2004) and violent suicides correlate with seasonal variation in n-3 intake (De Vriese, Christophe, & Maes, 2004). Also, serum n-3 PUFA levels predict serotonin and dopamine metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid that differ between violent and non-violent subjects (Hibbeln et al., 1998). Therefore, dietary-derived PUFA may influence behaviors related to psychiatric illness, potentially through mechanisms discussed above, although causality has not yet been established.

Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that we would find associations between measures of life functioning and concentrations of n-6 and n-3 lipids in serum. Specifically, we expected to find decreased levels of long chain n-3s or increased levels of long chain n-6s to associate with decreased functioning such as higher neuroticism, depression or mania scores and lower GAF scores. We use these scores as proxy measures of disease burden. These studies are cross-sectional and do not attempt to draw causality between lipid levels and behavior, but to provide a higher resolution understanding of the association between specific lipids within the n-3 and n-6 biosynthetic pathways and psychiatric metrics in order to guide future studies attempting dietary manipulation of tissue levels of these lipids to benefit treatment response in bipolar patients.

Neuroticism is a personality trait that is higher in bipolar subjects relative to non-psychiatric controls, and negatively associates with measures of life functionality (Suchy, Kraybill, & Franchow, 2011), like the Global Assessment of Function (GAF) scale. The Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) and Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) are measures of episodic depression and mania, respectively, which impede a patients’ ability to function normally. The current report explores the differences in PUFA profiles between bipolar subjects and healthy controls and associations of those profiles with these measures that correlate with life functioning. We analyzed plasma profiles of important n-3 and n-6 fatty acids within the biosynthetic pathway from short chain to long chain PUFA in 40 well-characterized bipolar subjects and 18 controls and compared them to the psychiatric measures, neuroticism, GAF, HAM-D and YMRS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The current study utilized psychiatric data and plasma samples obtained from 40 bipolar I and 18 control subjects, a subset of subjects recruited into the Prechter Longitudinal Study of Bipolar Disorder, described previously (Evans et al., 2012). Briefly, subjects were recruited carrying a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder or were non-psychiatric controls. All subjects participated in psychiatric testing that included the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS, (Nurnberger et al., 1994)), the revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R), the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D). We chose to normalize the NEO-PI-R data to the S-Form and all factors were calculated as per the NEO-PI-R manual (NEO PI-R professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. (Costa & McCrae, 1992)). Global Assessment of Function (GAF) measures were extracted from a clinician directed DIGS and reflected the clinician score of life functioning (Hall, 1995) over the month prior to the life interview. All blood samples were collected from subjects on the same day as the psychiatric testing. Blood samples were non-fasted and typically drawn between 9–11am and were drawn into lavendar-top vacutainer tubes (BD Sciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing EDTA. Tubes were centrifuged at 1200 × g to remove red blood cells and plasma was removed into 500ul aliquots and stored at −80C until used for lipomic analysis. All recruitment, enrolling and data analysis were done with the approval of the Institutional Review Board for human subject use at the University of Michigan and written consent for the studies was obtained from all subjects.

We focused our analysis of lipomic data on detectable lipids in the biosynthetic pathway from the essential 18 carbon fatty acids, LA and ALA, through desaturation and elongation to the 20 and 22 carbon lipids as shown in figure 1. We analyzed plasma levels of seven fatty acids in the n-3 and n-6 pathways, which include: 18:2n-6 (LA), 18:3n-6 (gamma-linoleic acid, GLA), 20:3n-6 (DGLA), 20:4n-6 (AA), 18:3n-3 (ALA), 20:5n-3 (EPA) and 22:6n-3 (DHA). We also assessed estimated activities of the FADS1 and FADS2 enzymes. For the present study, we analyzed plasma samples from 40 bipolar subjects (spanning low to high neuroticism scores) with a confirmed diagnosis of bipolar I disorder or healthy control using best estimates from the DIGS. Total lipids were extracted from the plasma according to the method of Bligh and Dyer (Bligh & Dyer, 1959). Heptadecanoic acid internal standards for lipid sub-classes were added to each sample prior to extraction. After hydrolysis, lipids were methylated and analyzed on an Omega Wax 250 capillary column (Supelco) using an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph. Relative abundance of 22 different naturally occurring fatty acid and 3 trans-fatty acid species were done by comparison of retention times with known standards. All fatty acids of interest for this manuscript were reliably detected in all samples. FADS1 and FADS2 activity estimates were calculated using the ratio of 20:4(n-6) to 20:3(n-6) and 18:3(n-6) to 18:2(n6), respectively. Bivariate correlation analyses between the above mentioned lipid and clinical metrics, were run on all subjects, followed by linear regression analyses of significant associations, separately for bipolar and control subjects.

Data were analyzed with SPSS 19 (IBM) and Prism (GraphPad) software, initially using a bivariate correlation analysis for the lipid concentration - psychiatric factor score correlations, with follow up analyses using linear regression, as described in the results section. Since age and BMI were moderately different between case and control groups, they were each controlled for using partial correlation analysis. However, they showed no effect on the conclusions, so are not included in the reported statistics. A Bonferroni multiple testing correction was applied separately to each grouped analysis (all subjects, bipolars, and controls), however, this method is likely overly stringent due to the lack of independence between psychiatric measures and the lack of independence between the concentrations of the lipid species. Therefore, the data is reported both with and with multiple testing corrected thresholds.

RESULTS

The mean and standard deviation of each of these lipid species from bipolar and control subjects plasma are also shown in Table 2, along with neuroticism, GAF, HAM-D and YMRS scores. All subjects used for these analyses were confirmed as carrying a diagnosis of bipolar I or non-psychiatric controls, based on the DIGS interviews and best estimates of diagnosis. No exclusions were applied to bipolar subjects for polypharmacy or comorbid metabolic illnesses, and the majority of bipolar subjects were being treated with a mixture of anti-depressants and mood stabilizers. A total of 23 bipolar I subjects were being treated with atypical antipsychotic and 36 were treated with anti-depressant medications. No bipolar II or bipolar NOS subjects were used in this study.

Table 2.

Summaries of psychiatric and lipid metrics.

| All Subjects | Bipolar I | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| mean (s.d.) | mean (s.d.) | mean (s.d.) | ttest | |

| neuroticism | 55.2 (16.5) | 62.7 (14.6) | 39.7 (6.50) | <0.001 |

| GAF | 76.6 (15.1) | 70.3 (15.3) | 87.6 (4.87) | <0.001 |

| HAM-D | 8.10 (10.6) | 11.3 (11.4) | 0.94 (1.76) | <0.001 |

| YMRS | 2.60 (5.65) | 3.58 (6.54) | 0.44 (1.42) | 0.050 |

|

| ||||

| LA | 25.1 (3.88) | 24.5 (3.95) | 2.62 (3.56) | 0.125 |

| GLA | 0.26 (0.13) | 0.27 (0.12) | 0.25 (0.13) | 0.560 |

| DGLA | 0.91 (0.26) | 0.96 (0.29) | 0.80 (0.14) | 0.033 |

| AA | 3.81 (1.00) | 3.86 (0.98) | 3.69 (1.05) | 0.547 |

|

| ||||

| ALA | 0.60 (0.28) | 0.59 (0.28) | 0.63 (0.28) | 0.595 |

| EPA | 0.14 (0.12) | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.14 (0.11) | 0.830 |

| DHA | 0.32 (0.14) | 0.31 (0.16) | 0.33 (0.11) | 0.641 |

|

| ||||

| FADS2 | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.99 (0.56) | 0.393 |

| FADS1 | 4.73 (3.34) | 4.76 (3.95) | 4.67 (1.29) | 0.929 |

Table shows mean and standard deviations for the indicated groups in the left three data columns with ttests for group differences between bipolars and controls shown in the right data column.

Metrics are global assessment of function (GAF), Hamilton depression scale (HAM-D), Young mania rating scale (YMRS), linoleic acid (LA), gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), dihomo-gammalinolenic acid (DGLA), alpha linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docoshexaenoic acid (DHA), fatty acid desaturase 1 (FADS1) and 2 (FADS2).

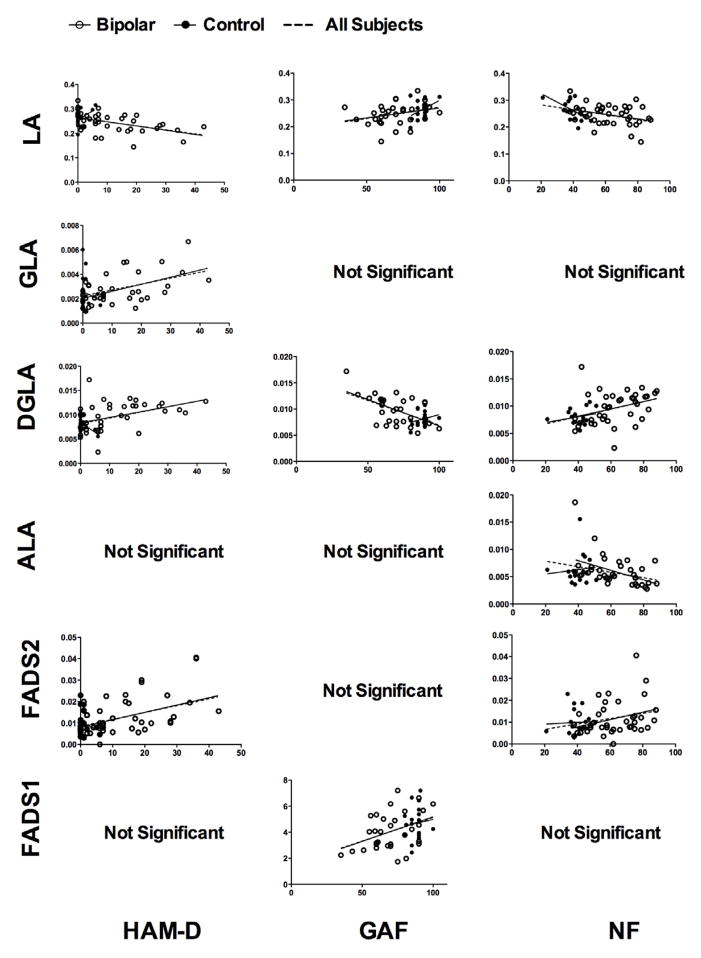

Correlation coefficients for associations between lipid concentrations and psychiatric measures are shown in Table 3. Analysis revealed several significant associations between plasma PUFA concentrations and neuroticism, GAF and HAM-D scores (Table 3 and Figure 2). In an all subject analyses, neuroticism negatively associated with LA and ALA (r=−0.398, p=0.002; r=−0.300, p=0.025, respectively) and positively associated with DGLA and FADS2 activity (r=0.428, p=0.001; r=0.294, p=0.029, respectively). GAF negatively associated with DGLA (r=0.582, p<0.001) and positively associated with LA and FADS1 activity (r=0.329, p=0.021; r=0.389, p=0.006, respectively). HAM-D negatively associated with LA (r=−0.450, p<0.001) and positively associated with GLA, DGLA and FADS2 (r=0.414, p=0.001; r=0.468, p<0.001; r=0.452, p<0.001, respectively). YMRS scores were not significantly associated with any of the assayed lipids. These p-values are not corrected for multiple testing because assumptions of independent tests are invalid due to the biosynthetic relationships and correlated concentrations between the lipids as well as the relationships between the psychiatric measurements. However, Bonferroni correction was applied, which is overly stringent in this case, and the associations that remained significant are bolded in table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of correlation coefficients and significance values from statistical tests.

| All subjects (n=58) | Bipolar I (n=40) | Control (n=18) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| GAF | NF | HAM-D | YMRS | GAF | NF | HAM-D | YMRS | GAF | NF | HAM-D | YMRS | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| LA | .329* | −.398** | −.450*** | −.224 | .284 | −.325* | −.502** | −.218 | .397 | −.577* | .364 | .060 |

| GLA | −.195 | .218 | .414** | .183 | −.304 | .303 | .539*** | .156 | −.146 | −.081 | −.164 | .519* |

| DGLA | −.582*** | .428** | .468*** | .203 | −.573** | .335* | .437** | .155 | .249 | .242 | −.495* | −.127 |

| AA | .012 | .108 | −.034 | −.096 | −.020 | .099 | −.076 | −.157 | .253 | −.083 | −.307 | .064 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| ALA | .147 | −.300* | −.226 | −.118 | .285 | −.454** | −.299 | −.118 | −.442 | .095 | .525* | −.072 |

| EPA | .022 | .080 | .156 | .062 | .015 | .073 | .198 | .032 | .436 | .039 | −.157 | .403 |

| DHA | −.070 | −.037 | −.014 | −.130 | −.150 | .003 | .018 | −.151 | .233 | −.145 | .007 | .269 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| FADS1 | .389** | −.066 | −.185 | −.021 | .400* | −.098 | −.219 | −.031 | .098 | −.152 | −.044 | .155 |

| FADS2 | −.260 | .297* | .481** | .235 | −.291 | .319 | .544*** | .205 | −.250 | .042 | −.221 | .434 |

Values shown are Pearson correlation coefficients with asterisk indicating significant correlations.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Values in bold remain significant at the p<0.05 level following Bonferroni correction.

Figure 2.

Regression scatter plots of significant associations from the all subject analyses. Data from bipolar subjects are given as an open circle and data from control subjects are given as a filled circle, each with a solid regression line shown. The dotted regression line represents a fit line through all subjects. P-values and correlation coefficients are given in Table 2.

Using linear regression analyses separating bipolar from control subjects, all associations found in the global analysis were significant in bipolar subjects, with the exceptions of GAF-LA and neuroticism-FADS2 associations. In control subjects, only the association between neuroticism and LA was consistent with the global analysis, suggesting bipolar subjects drove most of the significant associations. In controls, we also found a negative association between HAM-D and DGLA, and positive associations between HAM-D and ALA and between YMRS and GLA that were not seen in the global analysis, however the range of mood scores and GAF scores in the controls is so low that these latter described data are clinically meaningless and likely due to random variation in lipid levels. Correlation coefficients and p-values for all tests are given in table 2.

Since many of the bipolar subjects were taking anti-depressant or atypical anti-psychotic medications, we analyzed potential effects of these medications on the PUFA levels and the FADS activities. Student’s ttests found no differences between bipolar subjects taking and not currently taking these medications and multivariate linear regression analysis using binary dummy variables for antidepressant and atypical antipsychotic medication status (taking or not taking) showed no significant effect of either medication relative to any of the discussed PUFA profiles.

DISCUSSION

In the current manuscript we report significant associations between n3 and n6 PUFA plasma concentrations and neuroticism, GAF and HAM-D scores, which are using as proxy indicators of disease burden in bipolar disorder. Thus we found the short chain n-6, LA, and n-3, ALA, to associate with decreased neuroticism and increased functionality (for LA); and the long chain n-6, DGLA, to associate with increased neuroticism and depression, and decreased functionality. Furthermore the activity of FADS2, which would decrease concentrations of LA and ALA was positively associated with neuroticism and the activity of FADS1, which would decrease concentrations of DGLA was positively associated with GAF. These data suggest that a higher concentration of the short chain n-6 and n-3 PUFA may be beneficial.

In general, these data suggest that higher conversion of the substrates ALA and LA to their products by FADS2 is associated with increased markers of disease burden (neuroticism and HAM-D), while increased conversion of DGLA to its product by FADS1 may be associated with reduced markers of disease burden (GAF).

The findings were stronger in bipolar subjects than in controls, however, care must be taken in concluding a difference on these measures between cases and controls since the number of bipolar subjects and the statistical power to find associations was higher in the bipolar group. Furthermore, the range of neuroticism, GAF and HAM-D scores is naturally higher in bipolar subjects than in controls and we selected bipolar subjects to maximize this range, making any associations with the assayed lipids easier to detect. Associations between lipid concentrations and GAF and neuroticism scores may be found in control and psychiatric populations but only be problematic in the latter group due to other factors that mount to affect the burden of disease in the psychiatrically ill. We refrain from direct comparisons between bipolar and control subjects in our analysis because bipolar subjects were selected to represent a high neuroticism range, which was not possible for control subjects. This introduces a potential selection bias that makes it invalid for case control comparisons between lipids that associate with neuroticism score.

Out strongest findings are the associations between DGLA and the psychiatric measures, as these all passed a stringent Bonferroni multiple testing correction in the ‘all subject’ analysis. Interestingly DGLA has previously been shown to be increased in depressed adolescents (Mamalakis et al., 2006) and in seniors with mild cognitive impairment (Milte et al., 2011). Our data is consistent with these results suggesting that increased DGLA may associate with impaired mental function. DGLA has several known functions that might contribute to its potential role in this context. DGLA is a 20-carbon fatty acid, and is the precursor to the series-1 prostaglandins class of eicosanoids. DGLA can also be converted to AA, which is the precursor for series-2 prostaglandins. Our results initially appear somewhat paradoxical because depression is associated with pro-inflammatory states (Berk et al., 2011) and series-1 prostaglandins derived from DGLA are anti-inflammatory and compete to dampen the effects of inflammatory series-2 prostaglandins derived from AA. However, we did not directly assay prostaglandins, but their lipid precursors. A higher pool of DGLA that we see positively associated with neuroticism and depression scores and negatively associated with GAF scores might reflect an inefficient conversion of DGLA to series-2 prostaglandins and a deficit of these anti-inflammatory signaling molecules. This scenario would lead to an increased inflammatory state, which is associated with mood disorders. Direct prostaglandin measurement is problematic because these signaling molecules tend to act in a paracrine fashion and are short lived. However, our future work will assay cytokine levels (downstream of prostaglandin action) in addition to the lipid and psychiatric measurements to gain a more complete picture of this system.

The regulation of the cyclooxygenase enzymes that are responsible for converting DGLA to series-1 prostaglandins is highly complex and beyond the scope of this manuscript. However, some studies suggest that modulation of these enzymes may be efficacious in mood disorders (Muller, 2010). FADS activity, involved in the production of DGLA, can also be regulated by several factors. First, as discussed in the introduction, allelic variants in these genes influence PUFA levels. Activity is also influenced by dietary fats (Kirstein, Hoy, & Holmer, 1983) and activities of both FADS1 and FADS2 are modulated by several hormones involved in energy homeostasis (Brenner, 2003). Thus, the control of PUFA levels by diet, genetics and disease states are complex and understanding the potential role of DGLA in the regulation of mood disorders will require targeted further studies. As stated above, we plan to investigate the relationship between higher pools of DGLA and downstream cytokine markers of inflammatory state in bipolar and control subjects.

In summary, these data did not support our original hypothesis that we would find negative associations between long chain n-3s and disease burden or positive associations between AA and disease burden. However, we did find strong data associating DGLA with increases in depression and neuroticism scores and decrease in GAF scores. This is interesting, since most previous work has focused on EPA and DHA with some focus on AA. Our data suggests that a wider view of the biochemistry of n-3 and n-6 biosynthesis may be necessary to understand the relationship between these lipids and psychiatric illness.

The current study is, however, limited as a cross-sectional study from which we cannot draw any causative conclusions. Furthermore, there is a lack of independence between many of the associations we observe, since neuroticism, GAF and HAM-D scores are naturally different between bipolar subjects and controls, neuroticism is associated with GAF, and levels of the plasma lipids and FADS activities that we calculated are all correlated with each other as well. Regardless, the strength of the associations between DGLA and the disease measures (neuroticism, GAF and HAM-D) are intriguing and studies are proposed to ask whether or not dietary manipulation to control DGLA levels or relevant biosynthetic pathways would be beneficial in the control of bipolar disorder.

Table 1.

Subject demographics for the indicated data are shown separately for bipolar and control subjects.

| Bipolar I (n=40) | Control (n=18) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| % female | 60 | 61 | 0.873 |

| Age | 40.9 (±14.5) | 33.6 (±13.4) | 0.077 |

| BMI | 28 (±7.2) | 25 (±4.6) | 0.056 |

| % diabetic | 7.5 (3 of 40) | 0 (0 of 18) | 0.012 |

| % prescribed ADs | 87.5 | 0 | 0.001 |

| % prescribed AAPs | 55 | 0 | <0.001 |

Differences between the two groups are indicated by the p-values for the student’s ttest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Heinz C. Prechter Fund for Bipolar Research, directed by M.G. McInnis, the Michigan Nutrition Obesity Research Center (DK089503), directed by C.F. Burant, NIH Grant # 1K01MH093708-01A1 (S.J. Evans) and the Michigan Institute for Clinical Research, award number UL1RR024986 from the National Center for Research Resources. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTORS

SJE designed the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript, MK consulted on use of neuroticism and global assessment scores and selected subjects for analysis, ARP consulted on data analysis and selected subjects for analysis, GJH managed all aspects of the project, including data-basing and subject recruitment, VLE consulted on data analysis, MGM supervised all aspects of collection and consultation of psychiatric data, and CFB supervised and consulted on lipid assays.

DISCLOSURES

All authors report no financial conflicts of interest or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arterburn LM, Hall EB, Oken H. Distribution, interconversion, and dose response of n-3 fatty acids in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1467S–1476S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1467S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, Dean OM, Giorlando F, Maes M, Yucel M, Gama CS, Dodd S, Dean B, Magalhaes PV, Amminger P, McGorry P, Malhi GS. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:804–817. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner RR. Hormonal modulation of delta6 and delta5 desaturases: case of diabetes. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003;68:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(02)00265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalon S. Omega-3 fatty acids and monoamine neurotransmission. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;75:259–269. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Vriese SR, Christophe AB, Maes M. In humans, the seasonal variation in poly-unsaturated fatty acids is related to the seasonal variation in violent suicide and serotonergic markers of violent suicide. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004;71:13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SJ, Prossin AR, Harrington GJ, Kamali M, Ellingrod VL, Burant CF, McInnis MG. Fats and Factors: Lipid Profiles Associate with Personality Factors and Suicidal History in Bipolar Subjects. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyashiki T, Narumiya S. Stress responses: the contribution of prostaglandin E(2) and its receptors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawrisch K, Soubias O, Mihailescu M. Insights from biophysical studies on the role of polyunsaturated fatty acids for function of G-protein coupled membrane receptors. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008;79:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser C, Heinrich J, Koletzko B. Role of FADS1 and FADS2 polymorphisms in polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism. Metabolism. 2010;59:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haj-Dahmane S, Shen RY. Modulation of the serotonin system by endocannabinoid signaling. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RC. Global assessment of functioning. A modified scale Psychosomatics. 1995;36:267–275. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(95)71666-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR, Nieminen LR, Blasbalg TL, Riggs JA, Lands WE. Healthy intakes of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids: estimations considering worldwide diversity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1483S–1493S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1483S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbeln JR, Umhau JC, Linnoila M, George DT, Ragan PW, Shoaf SE, Vaughan MR, Rawlings R, Salem N., Jr A replication study of violent and nonviolent subjects: cerebrospinal fluid metabolites of serotonin and dopamine are predicted by plasma essential fatty acids. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:243–249. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huan M, Hamazaki K, Sun Y, Itomura M, Liu H, Kang W, Watanabe S, Terasawa K, Hamazaki T. Suicide attempt and n-3 fatty acid levels in red blood cells: a case control study in China. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:490–496. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirstein D, Hoy CE, Holmer G. Effect of dietary fats on the delta 6- and delta 5-desaturation of fatty acids in rat liver microsomes. Br J Nutr. 1983;50:749–756. doi: 10.1079/bjn19830146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Rao JS, Chang L, Rapoport SI, Kim HW. Chronic imipramine but not bupropion increases arachidonic acid signaling in rat brain: is this related to ‘switching’ in bipolar disorder? Mol Psychiatry. 2009;15:602–614. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, McNamara RK. Elevated Delta-6 desaturase (FADS2) gene expression in the prefrontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamalakis G, Kiriakakis M, Tsibinos G, Hatzis C, Flouri S, Mantzoros C, Kafatos A. Depression and serum adiponectin and adipose omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in adolescents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;85:474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Liu Y. Reduced expression of fatty acid biosynthesis genes in the prefrontal cortex of patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milte CM, Sinn N, Street SJ, Buckley JD, Coates AM, Howe PR. Erythrocyte polyunsaturated fatty acid status, memory, cognition and mood in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and healthy controls. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2011;84:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller N. COX-2 inhibitors as antidepressants and antipsychotics: clinical evidence. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:31–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW. Medical risk in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:e16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurnberger JI, Jr, Blehar MC, Kaufmann CA, York-Cooler C, Simpson SG, Harkavy-Friedman J, Severe JB, Malaspina D, Reich T. Diagnostic interview for genetic studies. Rationale, unique features, and training. NIMH Genetics Initiative. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:849–859. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950110009002. discussion 863–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport SI, Basselin M, Kim HW, Rao JS. Bipolar disorder and mechanisms of action of mood stabilizers. Brain Res Rev. 2009;61:185–209. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumock GT, Lee TA, Joo MJ, Valuck RJ, Stayner LT, Gibbons RD. Association between leukotriene-modifying agents and suicide: what is the evidence? Drug Saf. 2011;34:533–544. doi: 10.2165/11587260-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchy Y, Kraybill ML, Franchow E. Instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older adults: discrepancies between self-report and performance are mediated by cognitive reserve. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33:92–100. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.493148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME. STEP-BD and bipolar depression: what have we learned? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull T, Cullen-Drill M, Smaldone A. Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on improvement of bipolar symptoms: a systematic review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2008;22:305–311. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urade Y, Hayaishi O. Prostaglandin D2 and sleep/wake regulation. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]