Abstract

AIMS

To identify the most commonly prescribed drugs in a bariatric surgery population and to assess existing evidence regarding trends in oral drug bioavailability post bariatric surgery.

METHODS

A retrospective audit was undertaken to document commonly prescribed drugs amongst patients undergoing bariatric surgery in an NHS hospital in the UK and to assess practice for drug administration following bariatric surgery. The available literature was examined for trends relating to drug permeability and solubility with regards to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) and main route of elimination.

RESULTS

No significant difference in the ‘post/pre surgery oral drug exposure ratio’ (ppR) was apparent between BCS class I to IV drugs, with regards to dose number (Do) or main route of elimination. Drugs classified as ‘solubility limited’ displayed an overall reduction as compared with ‘freely soluble’ compounds, as well as an unaltered and increased ppR.

CONCLUSION

Clinical studies establishing guidelines for commonly prescribed drugs, and the monitoring of drugs exhibiting a narrow therapeutic window or without a readily assessed clinical endpoint, are warranted. Using mechanistically based pharmacokinetic modelling for simulating the multivariate nature of changes in drug exposure may serve as a useful tool in the further understanding of postoperative trends in oral drug exposure and in developing practical clinical guidance.

Keywords: bariatric surgery, biopharmaceutics classification system, CYP2C, CYP2D6, CYP3A, oral bioavailability

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Changes to oral drug bioavailability have been observed post bariatric surgery. However, the magnitude and the direction of changes have not been assessed systematically to provide insights into the parameters governing the observed trends. Understanding these can help with dose adjustments.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Analysis of drug characteristics based on a biopharmaceutical classification system is not adequate to explain observed trends in altered oral drug bioavailability following bariatric surgery, although the findings suggest solubility to play an important role.

Introduction

Obesity is generally defined by the body mass index (BMI = body weight (kg)/height (m)2). The classification is somewhat arbitrary such that ‘overweight’ means a BMI ≥ 25 but <30 kg m−2, ‘obesity’ refers to BMI ≥ 30 but <40 kg m−2 and ‘morbid obesity’ is a BMI ≥ 40 kg m−2 (this may also refer to being obese and suffering from related co-morbid conditions) [1, 2]. Over the last decade the prevalence of obesity has increased dramatically in the USA and Europe. In the USA 32.2% of the male and 35.5% of the female population over the age of 20 years were characterized as obese in 2007–2008 [3]. The United Kingdom has the highest reported obesity rate in Europe [4]. In England, 24.1% of the male and 24.9% of the female population over the age of 16 years were classified as obese in 2008 [5]. Bariatric surgery has proven to be successful in treating morbid obesity. In the USA and Canada approximately 200 000 bariatric surgeries were performed in 2008 [6]. In England 4221 surgeries were performed in 2008/09, an increase of over 100% since 2006/07 [1, 7]. Several bariatric surgical methods currently coexist in healthcare. These include the adjustable gastric band (AGBD), sleeve gastrectomy (SG), biliopancreatic diversion (BPD), biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) [8]. Other procedures, such as jejunoileal bypass (JIB), have been gradually phased out due to a higher likelihood of adverse events [9–11].

Bariatric surgical procedures have been well described in the literature [11, 12], where they are generally characterized as being restrictive, in terms of physiologically reducing dietary intake, malabsorptive, through reducing the ability of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to absorb nutrients or a combination of both.

Restrictive procedures such as AGBD and SG result in a reduced gastric capacity to 15–20 ml and 60–80 ml respectively [12, 13]. The JIB, considered a malabsorptive procedure, results in a 90–95% bypass of the small intestine, retaining the duodenum, proximal jejunum and terminal ileum [9–11]. The BPD-DS, primarily a malabsorptive procedure, results in a reduced gastric volume (100–175 ml) and bypass of larger parts of the small intestine, forming a biliopancreatic canal transporting the bile juices to the distal ileum [14, 15]. The RYGB, combining restriction and malabsorption, results in the restriction of the stomach to 15–30 ml and bypass of the proximal small intestine [15–17].

Bariatric surgery imposes a number of physiological alterations known to affect the bioavailability of orally administered drugs (Foral), dependent on the fraction of drug that is absorbed in the intestinal gut wall (fa), the fraction that escapes gut wall metabolism (fG), and the fraction that escapes hepatic metabolism (fH) (Equation 1).

| (1) |

fa and fG are highly influenced by drug specific properties, such as permeability and solubility, and the GI physiology such as gastric emptying time, GI pH profiles, small intestinal transit time, GI drug metabolizing enzymes and GI efflux transporters [18, 19]. Gastric emptying time can serve as the rate limiting step for highly permeable and highly soluble drugs as the absorption from the stomach is low [20]. The gastrointestinal pH may affect drug dissolution of permeability-limited drugs displaying a pKa within the range of the GI pH fluctuations. Small intestinal transit time can influence the drug absorption of poorly soluble or extended release drug formulations [18].

Metabolism in the gut acts to regulate oral bioavailability of drugs and other xenobiotics, and is an important determinant in the metabolism of substrate drugs [21]. CYP3A4 is the most abundant drug metabolizing enzyme in the GI tract, preceding CYP2C9/19 amongst others in order of appearance [22–25]. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 are both present along the GI tract, where CYP3A4 expression rises towards the jejunum to decrease towards the ileum [21, 26]. GI transporters may influence the absorption of orally administered drugs and potentially also the extent of metabolism in the gut through active substrate efflux [27]. Numerous transporters are present in the gut, where P-glycoprotein (P-gp) is perhaps the most extensively studied of the GI transporters. The relative expression pattern of P-gp in the small intestine increases from the proximal to the distal parts of the small intestine [28].

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) classifies drugs in accordance with their solubility and permeability. Solubility takes on the form of a dose number (Do), given by dividing highest dose strength in mg (MO) by a volume of 250 ml (VO) divided by the aqueous solubility of the drug (mg ml−1) over a pH range of 1.0–7.5 at 37°C (CS) [29]. Defining Do ≤ 1 as highly soluble and an fa≥ 90% as a highly permeable drug, drugs are classified as Class I (high solubility-high permeability), class II (poor solubility-high permeability), class III (high solubility-poor permeability) and class IV (poor solubility-poor permeability) [30].

The aims of this study were to identify the most commonly prescribed drugs in a bariatric surgery population and to assess existing evidence with respect to altered oral drug bioavailability post bariatric surgery. This would be carried out through methodologically reviewing the current literature, evaluating drug specific pharmacokinetic characteristics relating to solubility, permeability and main route of elimination.

Methods

Evaluation of drug utilization following gastric bypass

A retrospective audit of drug utilization by bariatric surgery patients was performed at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, Salford, UK. Data collection was performed using the hospitals electronic patient record (EPR) system, iSOFT clinical manager 1.4, which incorporates the medication prescription and administration records. A search of the EPR system was carried out for all patients under the care of a consultant bariatric surgeon. The search consisted of patients who had undergone surgery in the previous 5 months, from the 21 March 2011. The medical history of patients was initially searched to identify those having undergone laparoscopic RYGB. Patients who had a colostomy, gastric banding and reversal of gastric banding were excluded.

Data extraction was performed utilizsing an anonymous data collection form, maintaining patient confidentiality. Information extracted consisted of type of bariatric surgical procedure, pre surgery prescribed drug therapy and associated co-morbidities, post surgery medication including formulation changes and documented reasons behind alterations. Pre surgery medications were compared with the patients' medical charts on discharge, generally 2–3 days post surgery. Statistical analysis of trends in prescribed drugs observed during the retrospective audit was conducted using McNemar's non-parametric test (P≤ 0.05) in R v 2.12 (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Review and analysis of oral drug bioavailability following gastric bypass

Embase (1980–2010) and PubMed (1977–2010) were searched using the following combinations of keywords: ‘oral administration or bioavailability’, ‘absorption’, ’bioavailability’, ‘gastric bypass’, ‘jejunoileal bypass’, ‘bariatric surgery’. In addition, references of related articles were systematically investigated for relevant publications.

Initial screening of titles and abstracts was carried out to identify those compliant with pre specified criteria of reporting observational trends in bioavailability/oral drug exposure of pharmaceutical agents following bariatric surgery or the identification of adverse events related to oral drug exposure following surgery. Studies excluded consisted of gastric surgical procedures not related to obesity, reports on nutrients or supplementation post bariatric surgery and publications written in a language other than English. Screening was carried out to determine inclusion or exclusion criteria. Information extracted included study characteristics (surgical procedure, study design, number of participants, year of publication, country of origin and time since procedure) and study population characteristics (gender, average age, average body mass index (BMI) and co-morbidities). The principle measurement of bioavailability in the analysis was area under the curve (AUC), bioavailability and steady-state plasma or serum concentration.

Observed trends in oral drug exposure were assumed to follow a log normal distribution. Quantitative analysis was carried out through estimating the mean effect size of response ratios and their variance following a random-effect model. Statistical analysis was carried out with a two-tailed t-test of the standard normal cumulative distribution [31]. Statistical analysis between subgroups were carried out utilizing Welch's t-test (P≤ 0.05) of log-transformed weighted means and SDs with post hoc Dunn-Šidák correction (P≤ 0.05) using Microsoft® Excel 2003 and Matlab 2010 (the Mathworks Inc).

Results

Evaluation of clinical drug utilization following gastric bypass

The search of iSOFT identified 63 patients under the care of the bariatric surgeon and 38 patients (26 female) with a mean age of 45 (range 23–64) years were eligible for data extraction after fulfilling the pre-specified criteria. The surgical procedures performed included laparoscopic RYGB (n= 34), laparoscopic RYGB with abdominal wall hernia repair (n= 3) and conversion of AGBD to RYGB (n= 1). Commonly treated comorbidities amongst the study population included hypertension (n= 12), type 2 diabetes (n= 15), depression/anxiety (n= 11), hypothyroidism (n= 5), osteoarthritis (n= 11), hypercholesterolaemia (n= 10) and asthma (n= 9).

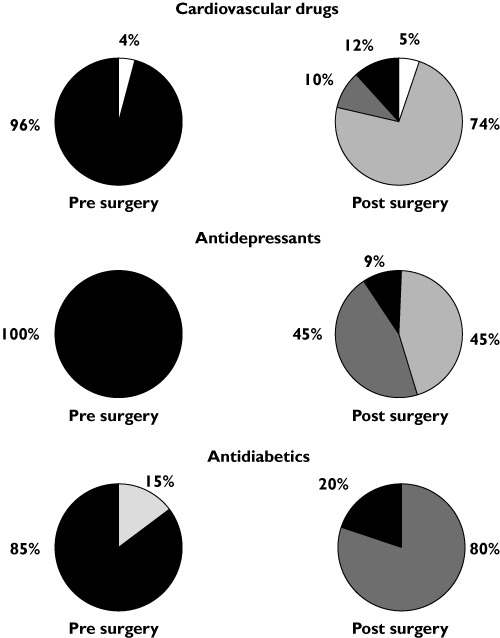

The most commonly prescribed drugs prior to surgery included statins (n= 13), ACE inhibitors (n= 10), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)/histamine H2-receptor antagonists (n= 10) and metformin (n= 10). Comparing pre to post surgery, a significant increase in the prescription of paracetamol, opioids, PPIs/histamine H2-receptor antagonists, heparin and antimicrobials was observed (P < 0.05) as well as an overall reduction in the number of patients treated for type 2 diabetes (P < 0.05). The most common drugs prescribed following surgery included heparin (n= 38), PPIs/histamine H2-receptor antagonists (n= 38) and paracetamol (n= 34). The number of patients prescribed cardiovascular agents remained constant postoperatively, whereas prescriptions of statins displayed a non-significant reduction of 31% (P > 0.05). The postoperative formulation of choice for diuretics was liquid (n= 4), whereas the remaining cardiovascular agents were tablets that were being crushed postoperatively (n= 28) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pharmacotherapeutic alterations in formulation properties (Solid = solid tablets, Liquid = liquid formulation, S/C = subcutaneous, Crushed = patients instructed to crush tablets, Inhaled = inhalation formulation) post bariatric surgery of prescribed cardiovascular drugs, antidepressants and antidiabetics as compared with prior to surgery observed in 38 evaluated patients. Solid ( ); Liquid (

); Liquid ( ); Crushed (

); Crushed ( ); S/C (

); S/C ( ); Inhaled (

); Inhaled ( )

)

All patients receiving antidepressants remained on the same antidepressant post surgery, with all but one receiving a different formulation. Of the 11 patients prescribed antidepressants, 50%were switched on to liquid formulations, whereas the remaining 50% were advised to crush their tablets post surgery (Figure 1). All patients with a prior diagnosis of diabetes underwent a diabetic review during their stay in hospital. The review resulted in a significant reduction in post-surgical prescriptions of anti-diabetic medications by 67% (P < 0.05). Patients who no longer required diabetic medication were alternatively switched to manual monitoring of blood glucose concentrations. Metformin was the only agent continued postoperatively and in 60% of cases continued at a reduced dose of up to a third of the pre-surgical dose level. All but one patient were converted to liquid preparations (Figure 1). Standard postoperative treatment consisted of 1–2 weeks low molecular weight heparin injection, PPIs (lansoprazole FasTab) and liquid formulation pain-killers (codeine and paracetamol) being prescribed for all patients. This patient group also displayed a significant increase in the prescription of PPIs/histamine H2 receptor antagonists, opioids, paracetamol and heparin (P < 0.05). One patient with a history of deep vein thrombosis remained on tinzaparin for 4 weeks.

Lansoprazole was given at a dose of 30 mg twice daily as a orodispersible formulation. The prophylactic therapy was to continue for at least 6 months postoperatively, before reducing the dose to once daily for a further 18 months. Approximately 2 weeks after surgery the sublingual formulation was switched to the solid tablet or capsule formulation.

Antimicrobials were given to seven patients postoperatively for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori (n= 5) that was detected from an intra-operative gastric mucosal biopsy, development of hospital-acquired pneumonia (n= 1) and anastomotic leakage (n= 1). All patients were given liquid preparations.

In total 17 patients were taking analgesics on a regular basis prior to surgery, increasing to 38 patients postoperatively. Analgesic products included paracetamol (n= 2, P < 0.05), aspirin (n= 5), opioids (n= 9, P < 0.05) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (n= 3). Patients taking NSAIDs prior to surgery (n= 3) were advised to stop taking these postoperatively due to an increased risk of developing gastro-jejunal anastomotic ulceration.

As stated in the patients ‘plan’ for postoperative care, a review of the nutritional progress usually occurred approximately 2 weeks post surgery. Patients were therefore advised to cease taking any non-essential vitamins and minerals immediately after surgery until the nutritional review has been completed. On discharge patients were informed that they would require taking lifelong dietary supplementation.

Oral drug bioavailability following bariatric surgery

The initial search of Embase and PubMed identified 311 potentially relevant publications based on search terms. After screening of abstracts, 66 articles were identified of which 22 matched the pre-specified criteria following full text screening. Overall, the literature search included 41 articles (20 controlled trials, 18 case reports and three case series) published between 1974 and 2011 that were suitable for further evaluation and data extraction.

Articles relating to JIB mainly appeared between 1974 and 1985. An increase of published data on RYGB was identified between 2000 and 2011, following the trend of RYGB being the most widely used bariatric surgical procedure at the present time [1].

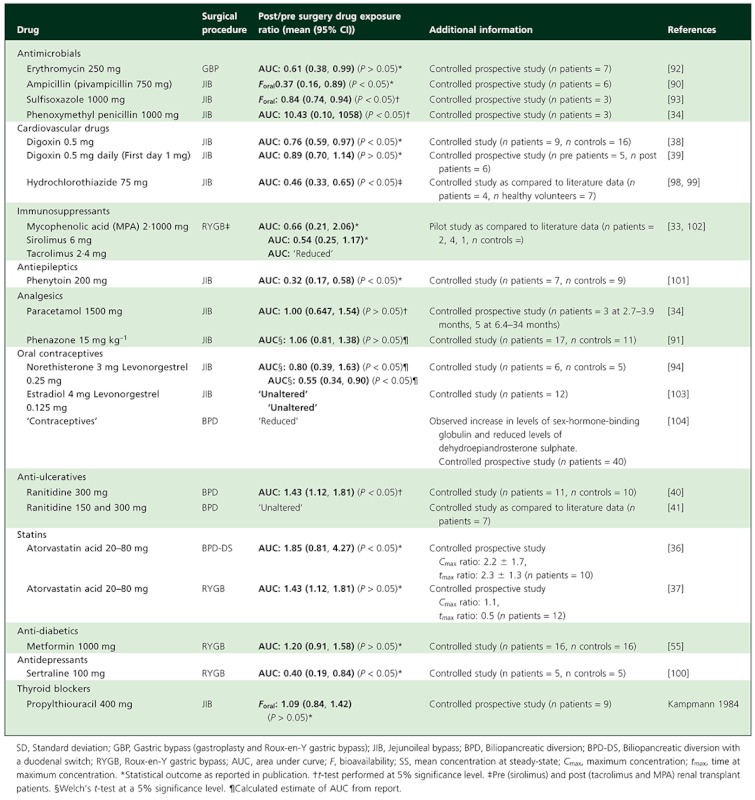

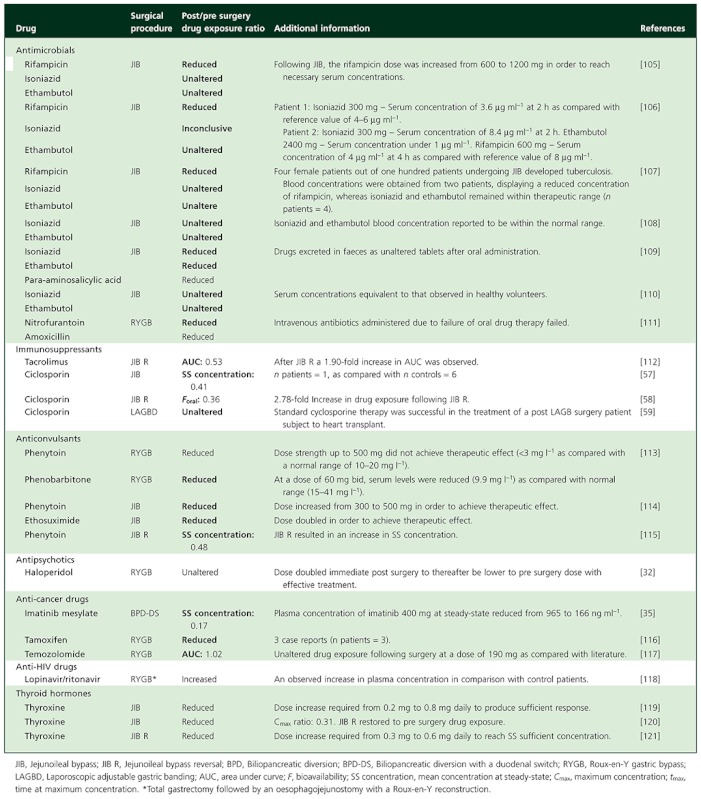

Surgical techniques identified included RYGB (n= 14), JIB (n= 19), reversal of jejunoileal bypass (JIB R) (n= 4), BPD-DS (n= 2) BPD (n= 3), GBP (n= 1) and AGB (n= 1) (Table 1). The 41 identified publications originated from the USA (58%), followed by the UK (10%), Italy (5%), Norway (5%) and Canada (5%).

Table 1.

Controlled trials examining the trend in oral drug exposure following bariatric surgery

| Drug | Surgery | Pre to post surgery oral drug exposure ratio (X, 95% CI)) | Patients (n) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ▴ | Phenoxymethyl penicillin 1000 mg | JIB | 10.43 (0.10, 1058)* | 3 | [34] |

| Atorvastatin acid 20–80 mg | BPD-DS | 1.85 (0.81, 4.27)† | 10 | [36] | |

| — | Ranitidine 300 mg | BPD | 1.43 (1.12, 1.81)* | 11 | [40] |

| Metformin 1000 mg | RYGB | 1.20 (0.91, 1.58)† | 16 | [55] | |

| Propylthiouracil 400 mg | JIB | 1.09 (0.84, 1.42)† | 6 | [90] | |

| Phenazone 15 mg kg−1 | JIB | 1.06 (0.81, 1.38)‡ | 17 | [91] | |

| Atorvastatin acid 20–80 mg | RYGB | 1.00 (0.29, 3.46)† | 12 | [37] | |

| Paracetamol 1500 mg | JIB | 1.00 (0.647, 1.54)* | 3 | [34] | |

| Digoxin 0.5 mg daily (First day: 1 mg) | JIB | 0.89 (0.70, 1.14)† | 7 | [39] | |

| Erythromycin 250 mg | GBP | 0.61 (0.38, 0.99)† | 7 | [92] | |

| ▾ | Sulfisoxazole 1000 mg | JIB | 0.84 (0.74, 0.94)* | 3 | [93] |

| Norethisterone 3 mg | JIB | 0.80 (0.39, 1.63)‡ | 6 | [94] | |

| Digoxin 0.5 mg | JIB | 0.76 (0.59, 0.97)† | 9 | [38] | |

| MMF 2·1000 mg | RYGB | 0.66 (0.21, 2.06)* | 2 | [33, 95] | |

| Levonorgestrel 0.25 mg | JIB | 0.55 (0.34, 0.90)‡ | 6 | [94] | |

| Sirolimus 8 mg | RYGB | 0.54 (0.25, 1.17)* | 4 | [33, 96, 97] | |

| Hydrochlorothiazide 75 mg | JIB | 0.46 (0.33, 0.65)* | 4 | [98, 99] | |

| Sertraline 100 mg | RYGB | 0.40 (0.19, 0.84)† | 5 | [100] | |

| Ampicillin (pivampicillin 750 mg) | JIB | 0.37 (0.16, 0.89)† | 5 | [90] | |

| Phenytoin 200 mg | JIB | 0.32 (0.17, 0.58)† | 7 | [101] |

▴= Indicating a significant increase in oral drug exposure (AUC, Foral or steady-state concentration) following surgery. —= No statistical significant change in oral drug exposure. ▾= Significant reduction in oral drug exposure. X = mean ratio change based on geometric mean, GBP, Gastric bypass (gastroplasty and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass); JIB, Jejunoileal bypass; BPD, Biliopancreatic diversion; BPDDS, Biliopancreatic dDiversion with a duodenal switch; RYGB, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil.

t-test performed at 5% significance level.

Statistical outcome as reported in publication.

Welch's t-test at a 5% significance level.

A total of 230 participants were studied in the identified publications. The time point for post surgical examination of oral drug exposure ranged from 0.1 to 88.9 months [32, 33]. In total 38 drugs were identified. These were categorically divided based on therapeutic indication. The studied drugs consisted of antimicrobials (n= 12 drugs), cardiovascular drugs (n= 2), immunosuppressants (n= 4), antiepileptics (n= 3), analgesics (n= 2), oral contraceptives (n= 4), anti-ulcer drugs (n= 1), statins (n= 1), thyroid hormones (n= 1), antidepressants (n= 2), anti-cancer drugs (n= 2), anti-diabetics (n= 1) and HIV medication (n= 1). Postoperative trends in drug bioavailability based on geometric mean drug exposure ranged from a 10.43 fold increase with a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 0.10 to 1058 (n= 32) [34] to a 5.88 fold reduction (n= 1) [35] (Table 1) [36–41]. The overall post/pre surgical oral drug exposure ratio (ppR) obtained from meta-analysis significantly diverged from pre surgery with a mean ppR of 0.80 with a 95% CI of 0.67, 0.94 (z value =−2.65, P < 0.01), when analyzing quantitative data providing mean and variance of exposure pre and post bariatric surgery.

Analysis in accordance to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System

Classifying drugs into BCS classification, class I (high solubility, high permeability), class II (low solubility, high permeability), class III (high solubility, low permeability) and class IV (low solubility, low permeability), identified eight drugs as BCS class I (n= 66 patients), three drugs as BCS class II (n= 7), eleven drugs as BCS class III (n= 53) and three drugs as BCS class IV (n= 8). A total of eight drugs were found to be inconclusive (n= 40). Information was lacking in the literature with regards to the BCS classification of pivampicillin, para-aminosalicylic acid and lopinavir/ritonavir.

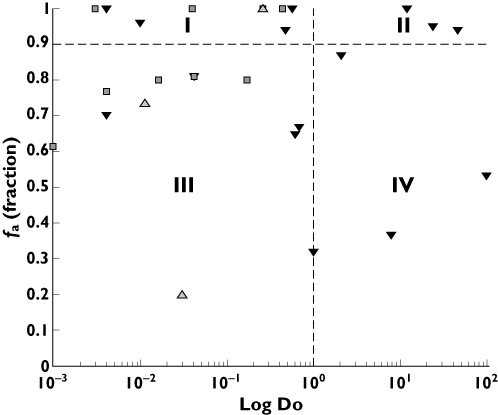

Of the eight drugs identified as BCS class I, four drugs displayed a reduction in exposure following surgery, four drugs remained unaltered and one drug displayed an increase in drug exposure. Out of eleven mapped BCS class III drugs, five displayed a reduction in drug exposure following surgery. An additional five drugs displayed unaltered drug exposure, whereas one drug displayed an increase. All BCS class II and IV drugs (total of six) displayed a reduction in drug exposure following surgery (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Categorical trends (reduced, unaltered and increased) in oral drug exposure in relation to fa (fraction of orally administered dose absorbed) and Do (dose number) in accordance with the BCS dividing drugs into BCS class I−IV [52, 60–89]. Reduced exposure (▾); Unaltered (□); Increased (▵).

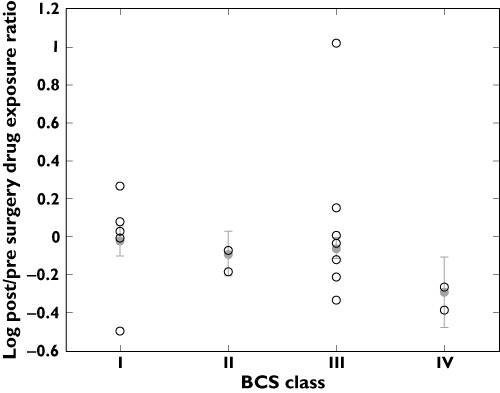

Analyzing BCS classified drugs where studies provided quantifiable measurements of drug exposure (i.e. AUC, Foral and plasma or serum concentrations), combining weighted means and variance of pre/post drug exposure ratio, BCS class I (n= 5 drugs, n= 108 population) displayed a weighted mean ppR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.66, 1.34). BCS class II (n= 2 drugs, n= 5 population) displayed a weighted mean ppR of 0.80 (95% CI 0.48, 1.36), BCS class III (n= 8 drugs, n= 111 population) showed a weighted mean ppR of 0.86 (95% CI 0.68, 1.10), whereas BCS class IV (n= 2 drugs, n= 17 population) displayed a weighted mean ppR of 0.51 (95% CI 0.22, 1.17). Statistical analysis did not reveal any significant differences from pre surgical ratio of 1 between BCS subgroups (P > 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Log mean post/pre surgery drug exposure ratio of BCS I-IV classified drugs. ○ log mean drug ratio, • combined log mean ratio and standard deviation of subgroup

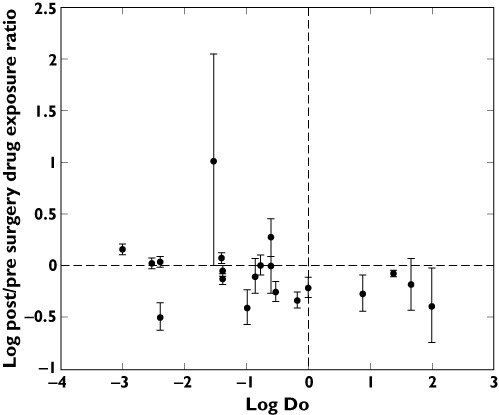

Drugs where studies provided quantifiable measurements of drug exposure were further statistically analyzed with regards to Do ≤ 1, BCS class I and III (n= 16 drugs, n= 262 population) vs. BCS class II and IV (n= 4 drugs, n= 48 patients). Do ≤ 1 drugs displayed a weighted mean ppR of 0.83 (0.69–1.00), whereas Do > 1 drugs displayed a ratio of 0.70 (95% CI 0.45, 1.10). Statistical analysis revealed no statistical significance from a pre surgical ratio of 1 or between subgroups (P > 0.05) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mean post/pre surgery drug exposure ratio and standard deviation in relation to quantitative Do (dose number)

Analysis in accordance to main route of elimination

Examining drugs in accordance with the main route of elimination produced a weighted mean ppR in oral drug exposure of 0.83 (95% CI 0.59, 1.17) for CYP3A4/5 substrates (n= 7 drugs, n= 99 patients), 0.32 (95% CI 0.14, 0.72) for CYP2C substrates (n= 1 drug, n= 16 population), 0.90 (95% CI 0.68, 1.18) for mainly renally-cleared drugs (n= 5 drugs, n= 103 population) and 0.76 (95% CI 0.57, 1.01) for the remaining drugs (n= 8 drugs, n= 92 population). Statistical analysis revealed no difference in ppR between the subgroups (P > 0.05), whereas the CYP2C subgroup significantly differed from the pre-surgical ratio of 1, displaying a z-value of −2.72 and P < 0.001.

Discussion

Evaluation of drug utilization following gastric bypass

The observed practice of altering formulation properties to liquid preparations is considered necessary in healthcare due to the postoperative condition of the patient rather than as a proactive measure against altered pharmacokinetics due to changes in GI physiology. Patients are advised to remain on liquid formulations for approximately 2–3 weeks, varying nationally to 3 months to lifelong, post bariatric surgery to prevent any unnecessary strain on the gastric and jejunal transection lines and the gastrojejunal anastomosis and therefore to allow time for healing. As an unintentional consequence changing to liquid preparations may result in an increase in oral bioavailability for solubility limited drugs.

Pharmacotherapeutic treatment of type 2 diabetes was ceased in 67% of patients following surgery. The prescription of metformin remained unaltered following surgery, albeit being observed to be significantly reduced 12 months postoperatively, by Malone & Alger-Mayer, following 114 patients up to 24 months post surgery [42].

Antidepressants, TCAs and SSRIs were continued immediately postoperatively in all cases. This was consistent with the report by Malone & Alger-Mayer, indicating prescriptions of TCAs and SSRIs remained statistically unaltered 12 months post surgery. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies are likely to occur indefinitely in the bariatric patient, resulting in the need for lifelong supplementation [43]. Deficiencies are most likely to occur with fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K), calcium and iron. Calcium and iron absorption is highly influenced by the reduction of hydrochloric acid production within the stomach after bariatric surgery [43].

Medication reviews have been performed observing modifications to patient dosing and formulation after bariatric surgery. Currently no consensus guidelines are available regarding considerations of pharmacotherapy post bariatric surgery. Evidence based national guidelines are warranted as bariatric surgery is becoming a more popular method for the treatment of obesity [44].

Oral drug exposure following bariatric surgery

Reviewing current data on changes in drug exposure prior to and post bariatric surgery reveals many uncertainties regarding the prediction of post bariatric surgery drug bioavailability and the mechanisms behind these changes. BCS did not prove to be enough to explain the observed trend.

Post bariatric surgery imposed restrictions on gastric volume (e.g. SG and RYGB) has been observed to reduce the gastric emptying time of liquids [45, 46] and may further lead to an increase in gastric pH [47, 48]. This together with a reduced fluid intake may impact on the solubility of orally administered drugs.

Statistical analysis did not present any significant trends when examining BCS class I-IV, Do or elimination subgroups. None of the Do > 1 classified drugs displayed an increase in bioavailability postoperatively, whereas the Do ≤ 1 group exhibited a larger variability in pre/post surgery drug exposure outcome. This may be due to solubility issues of the Do > 1 group, resulting in an overall reduction in oral drug exposure following surgery. The impact is however unclear due to a low number of drugs falling into the Do > 1 category, where further clinical data are necessary to establish the case.

Due to the restriction of the gastric volume following certain types of bariatric surgery (e.g. RYGB and BPD-DS) the default concomitant fluid intake of 250 ml in the BCS may no longer be valid. This will have implications for shifting the boundaries between BCS class I/III and II/IV, such that some freely soluble drugs may become solubility limited dependent on the administered dose. This is further complicated by a potentially altered gastric pH [11, 12, 29, 47, 48].

A small intestinal bypass will reduce the absorption area and may also alter the regional distribution and abundance of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporters thus altering exposure of substrate drugs. When examining drugs with respect to the main route of elimination, no significant difference was observed between CYP3A, CYP2C, renal and other drugs. These results were also associated with a high degree of uncertainty due to scarcity of data, albeit a higher ppR of CYP3A may be expected due to the GI abundance of CYP enzymes where CYP3A4 is the most highly abundant. The bypass of highly abundant regions of CYP3A4 may lead to an increase in oral bioavailability while such an effect may become less relevant for substrates due to decreasingly abundant CYP2C9/19 and CYP2D6. Such a hypothesis may be supported by the observed trend in AUC of atorvastatin acid, mainly metabolized by CYP3A4 [49], thus potentially displaying an increase in bioavailability post malabsorptive bariatric surgery due to the bypass of significant segments of GI regions highly abundant in CYP3A4 [26], whereas this effect may be counteracted by a reduced absorption area. Following BPD-DS a significant increase in AUC of atorvastatin acid (two-fold) was observed, whereas no significant change was observed following RYGB, thus potentially increasing the risk of adverse effects, such as myopathy, following BPD-DS [36, 37, 50].

The lack of quantifiable drug exposure data means that drugs displaying a low fG or limited absorption prior to surgery are likely to be wrongly classified when trying to generalize over a wide variety of drugs, such as metformin and phenoxymethylpenicillin.

Metformin, a highly soluble and permeability limited basic compound [51, 52], has been suggested to be subject to saturable transporter uptake to some extent by organic cation transporters in the intestine although this is not fully understood, thus resulting in a dose-dependent absorption that is mainly renally-cleared [53, 54]. The observed increase in postoperative bioavailability [55] might be due to altered small intestinal transit; reductions in gastric emptying time and small intestinal motility would in theory lead to a longer exposure time to enterocytic influx transporters. A further reason could be a post surgical alteration in transporter distribution patterns.

Phenoxymethylpenicillin, considered a highly soluble and permeable compound [52], displayed a significant increase in AUC post JIB, possibly due to a reduced intestinal degradation by bacterial β-lactamase due to a major small intestinal restriction [56].

The different surgical implications on GI physiology may result in variable trends in post surgery drug exposure across the range of bariatric procedures, as is the case with atorvastatin acid displaying a significant increase in AUC following the BPD-DS procedure as compared with no significant change following the less malabsorptive RYGB procedure [36, 37]. Also ciclosporin, there was a reduction in drug exposure following JIB, an exclusively malabsorptive procedure [57, 58], as compared with remaining unaltered following the restrictive AGB [59].

The outcomes of oral drug exposure of many commonly prescribed drugs in bariatric surgery populations are still unknown, such as many antidepressants and analgesics. Current available clinical data are very valuable. Going forward it is important that further clinical studies are designed taking into consideration the potential alterations in concentration−time profiles, relating to pharmacokinetic parameters such as tmax. Drugs exhibiting a narrow therapeutic range or displaying less readily measurable clinical endpoints will require more stringent monitoring after bariatric surgery, such as immunosuppressant agents and CNS active drugs.

Due to the multiple physiological factors altered in bariatric surgery (i.e. gastric volume, absorption area, CYP-abundance and regional distribution) [11, 12], and the fact that various drugs might be affected to different degrees by each of these changes, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling may help in elucidating the impact of various bariatric surgeries on different drugs given at different doses. Such an investigation was outside the scope of the current research. However initial attempts on this approach are addressed in another report (Darwich et al. submitted and under review) where the complex nature of interplays were manifested.

In conclusion, based on current findings, analysis of general pharmacokinetic parameters alone (i.e. solubility, permeability and main route of elimination) is not enough to explain observed trends in oral drug bioavailability following bariatric surgery, although the findings of this study suggest solubility to potentially play an important role.

These implications support the hypothesis that there are several physiologic and drug-specific parameters which govern the observed changes in drug exposure, thus calling for a more mechanistic approach, integrating all known parameters.

To the authors' knowledge this is the first publication quantitatively examining oral drug bioavailability in relation to a set of pharmacokinetic, biopharmaceutic and other drug-specific parameters and also in the context of pharmacotherapeutic practice following bariatric surgery. Along with further clinical studies, PBPK modelling may provide essential insights into the significance of individual pharmacokinetic parameters and generate important clinical guidance for a constantly growing post bariatric surgery population. Currently, there seems to be no simple algorithm or decision tree that predicts the variable changes to drug bioavailability following bariatric surgery.

Appendix

Table A1.

Controlled trials examining oral drug bioavailability following bariatric surgery

|

Table A2.

Case reports (n patients = 1) on oral drug bioavailability following bariatric surgery

|

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL, Gospodarevskaya E, Loveman E, Baxter L, Clegg AJ. The clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:1–358. doi: 10.3310/hta13410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fact Sheet 311. eneva: World Health Organisation; 2006. Obesity and Overweight. Available at http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/ (last accessed 8 November 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sassi F. Obesity and the Economics of Prevention: Fit Not Fat – United Kingdom (England) Key Facts. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, London; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Neill P. Office of Health Economics, UK. Shedding the Pounds: Obesity Management, NICE Guidance and Bariatric Surgery in England. London: Office of Health Economics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery Worldwide 2008. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1605–11. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The NHS Information Centre. Lifestyle Statistics. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet: England, 2010, First Edition. Leeds: The Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Bariatric Surgery for Severe Obesity. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh D, Laya AS, Clarkston WK, Allen MJ. Jejunoileal bypass: a surgery of the past and a review of its complications. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2277–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffen WO, Jr, Young VL, Stevenson CC. A prospective comparison of gastric and jejunoileal bypass procedures for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1977;186:500–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197710000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder KA, Wolfe BM. Bariatric surgery: a review of procedures and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2253–71. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider BE, Mun EC. Surgical management of morbid obesity. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:475–80. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CM, Cirangle PT, Jossart GH. Vertical gastrectomy for morbid obesity in 216 patients: report of two-year results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1810–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9276-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hess DS, Hess DW. Biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch. Obes Surg. 1998;8:267–82. doi: 10.1381/096089298765554476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spak E, Bjorklund P, Helander HF, Vieth M, Olbers T, Casselbrant A, Lonroth H, Fandriks L. Changes in the mucosa of the Roux-limb after gastric bypass surgery. Histopathology. 2010;57:680–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeMaria EJ, Sugerman HJ, Kellum JM, Meador JG, Wolfe LG. Results of 281 consecutive total laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses to treat morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2002;235:640–5. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200205000-00005. discussion 45–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wittgrove AC, Clark GW. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y- 500 patients: technique and results, with 3-60 month follow-up. Obes Surg. 2000;10:233–9. doi: 10.1381/096089200321643511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowland M, Tozer TN. In: Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Concepts and Applications. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jamei M, Turner D, Yang J, Neuhoff S, Polak S, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker G. Population-based mechanistic prediction of oral drug absorption. AAPS J. 2009;11:225–37. doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9099-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higaki K, Choe SY, Lobenberg R, Welage LS, Amidon GL. Mechanistic understanding of time-dependent oral absorption based on gastric motor activity in humans. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;70:313–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolars JC, Lown KS, Schmiedlin-Ren P, Ghosh M, Fang C, Wrighton SA, Merion RM, Watkins PB. CYP3A gene expression in human gut epithelium. Pharmacogenetics. 1994;4:247–59. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paine MF, Hart HL, Ludington SS, Haining RL, Rettie AE, Zeldin DC. The human intestinal cytochrome P450 ‘pie’. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:880–6. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.008672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher MB, Paine MF, Strelevitz TJ, Wrighton SA. The role of hepatic and extrahepatic UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in human drug metabolism. Drug Metab Rev. 2001;33:273–97. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120000653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riches Z, Stanley EL, Bloomer JC, Coughtrie MW. Quantitative evaluation of the expression and activity of five major sulfotransferases (SULTs) in human tissues: the SULT ‘pie’. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2255–61. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.028399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters WH, Roelofs HM, Nagengast FM, van Tongeren JH. Human intestinal glutathione S-transferases. Biochem J. 1989;257:471–6. doi: 10.1042/bj2570471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paine MF, Khalighi M, Fisher JM, Shen DD, Kunze KL, Marsh CL, Perkins JD, Thummel KE. Characterization of interintestinal and intraintestinal variations in human CYP3A-dependent metabolism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:1552–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benet LZ, Cummins CL. The drug efflux-metabolism alliance: biochemical aspects. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;50(Suppl. 1):S3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mouly S, Paine MF. P-glycoprotein increases from proximal to distal regions of human small intestine. Pharm Res. 2003;20:1595–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1026183200740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry: Waiver of In Vivo Bioavailability and Bioequivalence Studies for Immediate-Release Solid Oral Dosage Forms Based on A Biopharmaceutics Classification System. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amidon GL, Lennernas H, Shah VP, Crison JR. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharm Res. 1995;12:413–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1016212804288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fuller AK, Tingle D, DeVane CL, Scott JA, Stewart RB. Haloperidol pharmacokinetics following gastric bypass surgery. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1986;6:376–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers CC, Alloway RR, Alexander JW, Cardi M, Trofe J, Vinks AA. Pharmacokinetics of mycophenolic acid, tacrolimus and sirolimus after gastric bypass surgery in end-stage renal disease and transplant patients: a pilot study. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:281–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terry SI, Gould JC, McManus JP, Prescott LF. Absorption of penicillin and paracetamol after small intestinal bypass surgery. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;23:245–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00547562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu H, Artz AS. Reduction of imatinib absorption after gastric bypass surgery. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:310–3. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.532890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skottheim IB, Jakobsen GS, Stormark K, Christensen H, Hjelmesaeth J, Jenssen T, Asberg A, Sandbu R. Significant increase in systemic exposure of atorvastatin after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87:699–705. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skottheim IB, Stormark K, Christensen H, Jakobsen GS, Hjelmesaeth J, Jenssen T, Reubsaet JL, Sandbu R, Asberg A. Significantly altered systemic exposure to atorvastatin acid following gastric bypass surgery in morbidly obese patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86:311–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gerson CD, Lowe EH, Lindenbaum J. Bioavailability of digoxin tablets in patients with gastrointestinal dysfunction. Am J Med. 1980;69:43–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcus FI, Quinn EJ, Horton H, Jacobs S, Pippin S, Stafford M, Zukoski C. The effect of jejunoileal bypass on the pharmacokinetics of digoxin in man. Circulation. 1977;55:537–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.55.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cossu ML, Caccia S, Coppola M, Fais E, Ruggiu M, Fracasso C, Nacca A, Noya G. Orally administered ranitidine plasma concentrations before and after biliopancreatic diversion in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 1999;9:36–9. doi: 10.1381/096089299765553728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adami GF, Gandolfo P, Esposito M, Scopinaro N. Orally-administered serum ranitidine concentration after biliopancreatic diversion for obesity. Obes Surg. 1991;1:293–94. doi: 10.1381/096089291765561024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malone M, Alger-Mayer SA. Medication use patterns after gastric bypass surgery for weight management. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:637–42. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ponsky TA, Brody F, Pucci E. Alterations in gastrointestinal physiology after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buchwald H, Williams SE. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2003. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1157–64. doi: 10.1381/0960892042387057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horowitz M, Cook DJ, Collins PJ, Harding PE, Hooper MJ, Walsh JF, Shearman DJ. Measurement of gastric emptying after gastric bypass surgery using radionuclides. Br J Surg. 1982;69:655–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800691108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Braghetto I, Davanzo C, Korn O, Csendes A, Valladares H, Herrera E, Gonzalez P, Papapietro K. Scintigraphic evaluation of gastric emptying in obese patients submitted to sleeve gastrectomy compared to normal subjects. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1515–21. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith CD, Herkes SB, Behrns KE, Fairbanks VF, Kelly KA, Sarr MG. Gastric acid secretion and vitamin B12 absorption after vertical Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1993;218:91–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199307000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Behrns KE, Smith CD, Sarr MG. Prospective evaluation of gastric acid secretion and cobalamin absorption following gastric bypass for clinically severe obesity. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:315–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02090203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lennernas H, Fager G. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Similarities and differences. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:403–25. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Omar MA, Wilson JP, Cox TS. Rhabdomyolysis and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1096–107. doi: 10.1345/aph.10228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van de Merbel NC, Wilkens G, Fowles S, Oosterhuis B, Jonkman JHG. LC phases improve, but not all assays do: metformin bioanalysis revisited. Chromatographia. 1998;47:542–46. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kasim NA, Whitehouse M, Ramachandran C, Bermejo M, Lennernas H, Hussain AS, Junginger HE, Stavchansky SA, Midha KK, Shah VP, Amidon GL. Molecular properties of WHO essential drugs and provisional biopharmaceutical classification. Mol Pharm. 2004;1:85–96. doi: 10.1021/mp034006h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tucker GT, Casey C, Phillips PJ, Connor H, Ward JD, Woods HF. Metformin kinetics in healthy subjects and in patients with diabetes mellitus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;12:235–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Proctor WR, Bourdet DL, Thakker DR. Mechanisms underlying saturable intestinal absorption of metformin. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:1650–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.020180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Padwal RS, Gabr RQ, Sharma AM, Langkaas LA, Birch DW, Karmali S, Brocks DR. Effect of gastric bypass surgery on the absorption and bioavailability of metformin. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1295–300. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cole M, Kenig MD, Hewitt VA. Metabolism of penicillins to penicilloic acids and 6-aminopenicillanic acid in man and its significance in assessing penicillin absorption. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973;3:463–8. doi: 10.1128/aac.3.4.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chenhsu RY, Wu Y, Katz D, Rayhill S. Dose-adjusted cyclosporine c2 in a patient with jejunoileal bypass as compared to seven other liver transplant recipients. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25:665–70. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knight GC, Macris MP, Peric M, Duncan JM, Frazier OH, Cooley DA. Cyclosporine A pharmacokinetics in a cardiac allograft recipient with a jejuno-ileal bypass. Transplant Proc. 1988;20:351–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ablassmaier B, Klaua S, Jacobi CA, Muller JM. Laparoscopic gastric banding after heart transplantation. Obes Surg. 2002;12:412–5. doi: 10.1381/096089202321088273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chemical C. Product Information – Imatinib (Mesylate) Ann Arbor, MI: Cayman Chemical Company; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 61.FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ni J, Ouyang H, Aiello M, Seto C, Borbridge L, Sakuma T, Ellis R, Welty D, Acheampong A. Microdosing assessment to evaluate pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in rats using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1572–82. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ashiru DA, Patel R, Basit AW. Polyethylene glycol 400 enhances the bioavailability of a BCS class III drug (ranitidine) in male subjects but not females. Pharm Res. 2008;25:2327–33. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9635-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindenberg M, Kopp S, Dressman JB. Classification of orally administered drugs on the World Health Organization Model list of Essential Medicines according to the biopharmaceutics classification system. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;58:265–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu CY, Benet LZ. Predicting drug disposition via application of BCS: transport/absorption/ elimination interplay and development of a biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system. Pharm Res. 2005;22:11–23. doi: 10.1007/s11095-004-9004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oie S, Gambertoglio JG, Fleckenstein L. Comparison of the disposition of total and unbound sulfisoxazole after single and multiple dosing. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1982;10:157–72. doi: 10.1007/BF01062333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaplan SA, Weinfeld RE, Abruzzo CW, Lewis M. Pharmacokinetic profile of sulfisoxazole following intravenous, intramuscular, and oral administration to man. J Pharm Sci. 1972;61:773–8. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600610521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yalkowsky SH, He Y. Handbook of Aqueous Solubility Data. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lennernas H, Gjellan K, Hallgren R, Graffner C. The influence of caprate on rectal absorption of phenoxymethylpenicillin: experience from an in-vivo perfusion in humans. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2002;54:499–508. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stewart BH, Chan OH, Lu RH, Reyner EL, Schmid HL, Hamilton HW, Steinbaugh BA, Taylor MD. Comparison of intestinal permeabilities determined in multiple in vitro and in situ models: relationship to absorption in humans. Pharm Res. 1995;12:693–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1016207525186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bock U, Kottke T, Gindorf C, Haltner E. Saarbrucken: Across Barriers; 2003. >Validation of the Caco-2 cell monolayer system for determining the permeability of drug substances according to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) pp. 1–7. Available at http://www.acrossbarriers.de/uploads/media/FCT02-I-0305_BCS_01.pdf (last accessed 8 November 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dressman JB, Amidon GL, Fleisher D. Absorption potential: estimating the fraction absorbed for orally administered compounds. J Pharm Sci. 1985;74:588–9. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600740523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Garekani HA, Sadeghi F, Ghazi A. Increasing the aqueous solubility of acetaminophen in the presence of polyvinylpyrrolidone and investigation of the mechanisms involved. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2003;29:173–9. doi: 10.1081/ddc-120016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. Sixty-Second edn. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crowe A, Lemaire M. In vitro and in situ absorption of SDZ-RAD using a human intestinal cell line (Caco-2) and a single pass perfusion model in rats: comparison with rapamycin. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1666–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1011940108365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tamura S, Ohike A, Ibuki R, Amidon GL, Yamashita S. Tacrolimus is a class II low-solubility high-permeability drug: the effect of P-glycoprotein efflux on regional permeability of tacrolimus in rats. J Pharm Sci. 2002;91:719–29. doi: 10.1002/jps.10041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tavelin S, Milovic V, Ocklind G, Olsson S, Artursson P. A conditionally immortalized epithelial cell line for studies of intestinal drug transport. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1212–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petan JA, Undre N, First MR, Saito K, Ohara T, Iwabe O, Mimura H, Suzuki M, Kitamura S. Physiochemical properties of generic formulations of tacrolimus in Mexico. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1439–42. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kearney AS, Crawford LF, Mehta SC, Radebaugh GW. The interconversion kinetics, equilibrium, and solubilities of the lactone and hydroxyacid forms of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, CI-981. Pharm Res. 1993;10:1461–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1018923325359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lennernas H. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atorvastatin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:1141–60. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342130-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Song NN, Li QS, Liu CX. Intestinal permeability of metformin using single-pass intestinal perfusion in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4064–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kampmann J, Skovsted L. The pharmacokinetics of propylthiouracil. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1974;35:361–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1974.tb00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peloquin CA, Namdar R, Singleton MD, Nix DE. Pharmacokinetics of rifampin under fasting conditions, with food, and with antacids. Chest. 1999;115:12–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Becker C, Dressman JB, Amidon GL, Junginger HE, Kopp S, Midha KK, Shah VP, Stavchansky S, Barends DM. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: ethambutol dihydrochloride. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97:1350–60. doi: 10.1002/jps.21061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nelson E, Powell JR, Conrad K, Likes K, Byers J, Baker S, Perrier D. Phenobarbital pharmacokinetics and bioavailability in adults. J Clin Pharmacol. 1982;22:141–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1982.tb02662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patel IH, Levy RH, Bauer TG. Pharmacokinetic properties of ethosuximide in monkeys. I. Single-dose intravenous and oral administration. Epilepsia. 1975;16:705–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1975.tb04755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bolton AE, Peng B, Hubert M, Krebs-Brown A, Capdeville R, Keller U, Seiberling M. Effect of rifampicin on the pharmacokinetics of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, STI571) in healthy subjects. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:102–6. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wenzel KW, Kirschsieper HE. Aspects of the absorption of oral L-thyroxine in normal man. Metabolism. 1977;26:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(77)90121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.NCBI PubChem Public Chemical Database. National Center of Biotechnology Information. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Health; 2011. Available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ (last accessed 8 November 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kampmann JP, Klein H, Lumholtz B, Molholm Hansen JE. Ampicillin and propylthiouracil pharmacokinetics in intestinal bypass patients followed up to a year after operation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1984;9:168–76. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198409020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andreasen PB, Dano P, Kirk H, Greisen G. Drug absorption and hepatic drug metabolism in patients with different types of intestinal shunt operation for obesity. A study with phenazone. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1977;12:531–5. doi: 10.3109/00365527709181330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Prince RA, Pincheira JC, Mason EE, Printen KJ. Influence of bariatric surgery on erythromycin absorption. J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;24:523–7. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1984.tb02762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garrett ER, Suverkrup RS, Eberst K, Yost RL, O'Leary JP. Surgically affected sulfisoxazole pharmacokinetics in the morbidly obese. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1981;2:329–65. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510020405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Victor A, Odlind V, Kral JG. Oral contraceptive absorption and sex hormone binding globulins in obese women: effects of jejunoileal bypass. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1987;16:483–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Genentech. Cellcept Prescribing Information. San Fransisco, CA: Genentech USA Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mathew TH, Van Buren C, Kahan BD, Butt K, Hariharan S, Zimmerman JJ. A comparative study of sirolimus tablet versus oral solution for prophylaxis of acute renal allograft rejection. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:76–87. doi: 10.1177/0091270005282628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Brattstrom C, Sawe J, Jansson B, Lonnebo A, Nordin J, Zimmerman JJ, Burke JT, Groth CG. Pharmacokinetics and safety of single oral doses of sirolimus (rapamycin) in healthy male volunteers. Ther Drug Monit. 2000;22:537–44. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200010000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Backman L, Beerman B, Groschinsky-Grind M, Hallberg D. Malabsorption of hydrochlorothiazide following intestinal shunt surgery. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1979;4:63–8. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197904010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Beermann B, Groschinsky-Grind M. Pharmacokinetics of hydrochlorothiazide in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;12:297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00607430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roerig JL, Steffen K, Zimmerman C, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Cao L. Preliminary comparison of sertraline levels in postbariatric surgery patients versus matched nonsurgical cohort. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:62–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kennedy MC, Wade DN. Phenytoin absorption in patients with ileojejunal bypass. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979;7:515–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dowell JA, Stogniew M, Krause D, Henkel T, Damle B. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between anidulafungin and tacrolimus. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47:305–14. doi: 10.1177/0091270006296764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Andersen AN, Lebech PE, Sorensen TI, Borggaard B. Sex hormone levels and intestinal absorption of estradiol and D-norgestrel in women following bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Int J Obes. 1982;6:91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gerrits EG, Ceulemans R, van Hee R, Hendrickx L, Totte E. Contraceptive treatment after biliopancreatic diversion needs consensus. Obes Surg. 2003;13:378–82. doi: 10.1381/096089203765887697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Griffiths TM, Thomas P, Campbell IA. Antituberculosis drug levels after jejunoileal bypass. Br J Dis Chest. 1982;76:286–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Harris JO, Wasson KR. Tuberculosis after intestinal bypass operation for obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:115–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-1-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bruce RM, Wise L. Tuberculosis after jejunoileal bypass for obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:574–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-5-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pickleman JR, Evans LS, Kane JM, Freeark RJ. Tuberculosis after jejunoileal bypass for obesity. JAMA. 1975;234:744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Werbin N. Tuberculosis after jejuno-ileal bypass for morbid obesity. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:252–3. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.57.666.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Polk RE, Tenenbaum M, Kline B. Isoniazid and ethambutol absorption with jejunoileal bypass. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:430–1. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-3-430_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Magee SR, Shih G, Hume A. Malabsorption of oral antibiotics in pregnancy after gastric bypass surgery. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:310–3. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kelley M, Jain A, Kashyap R, Orloff M, Abt P, Wrobble K, Venkataramanan R, Bozorgzadeh A. Change in oral absorption of tacrolimus in a liver transplant recipient after reversal of jejunoileal bypass: case report. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3165–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pournaras DJ, Footitt D, Mahon D, Welbourn R. Reduced phenytoin levels in an epileptic patient following Roux-En-Y gastric bypass for obesity. Obes Surg. 2011;21:684–5. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Peterson DI, Zweig RW. Absorption of anticonvulsants after jejunoileal bypass. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc. 1974;39:51–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Peterson DI. Phenytoin absorption following jejunoileal bypass. Bull Clin Neurosci. 1983;48:148–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Wills SM, Zekman R, Bestul D, Kuwajerwala N, Decker D. Tamoxifen malabsorption after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: case series and review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;30:217. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Park DM, Shah DD, Egorin MJ, Beumer JH. Disposition of temozolomide in a patient with glioblastoma multiforme after gastric bypass surgery. J Neurooncol. 2009;93:279–83. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Boffito M, Lucchini A, Maiello A, Dal Conte I, Hoggard PG, Back DJ, Di Perri G. Lopinavir/ritonavir absorption in a gastrectomized patient. AIDS. 2003;17:136–7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200301030-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Topliss DJ, Wright JA, Volpe R. Increased requirement for thyroid hormone after a jejunoileal bypass operation. Can Med Assoc J. 1980;123:765–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Azizi F, Belur R, Albano J. Malabsorption of thyroid hormones after jejunoileal bypass for obesity. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:941–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-6-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bevan JS, Munro JF. Thyroxine malabsorption following intestinal bypass surgery. Int J Obes. 1986;10:245–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]