Abstract

AIMS

Our study aimed to examine the impact of concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) with clopidogrel on the cardiovascular outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Furthermore, we sought to quantify the effects of five individual PPIs when used concomitantly with clopidogrel.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who were newly hospitalized for ACS between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2007 retrieved from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) and who were prescribed clopidogrel (n= 37 099) during the follow-up period. A propensity score technique was used to establish a matched cohort in 1:1 ratio (n= 5173 for each group). The primary clinical outcome was rehospitalization for ACS, while secondary outcomes were rehospitalization for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) with stent, PTCA without stent and revascularization (PTCA or coronary artery bypass graft surgery) after the discharge date for the index ACS event.

RESULTS

The adjusted hazard ratio of rehospitalization for ACS was 1.052 (95% confidence interval, 0.971–1.139; P= 0.214) in the propensity score matched cohort. Among all PPIs, only omeprazole was found to be statistically significantly associated with an increased risk of rehospitalization for ACS (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.226; 95% confidence interval, 1.066–1.410; P= 0.004). Concomitant use of esomeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and lansoprazole did not increase the risk.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study indicated no statistically significant increase in the risk of rehospitalization for ACS due to concurrent use of clopidogrel and PPIs overall. Among individual PPIs, only omeprazole was found to be statistically significantly associated with increased risk of rehospitalization for ACS.

Keywords: adverse event, cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular risk, clopidogrel, drug–drug interaction, pharmacotherapy

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

Conflicting results have been reported regarding the increased risk of adverse outcomes in the concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) compared with the use of clopidogrel alone.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Our study indicated no statistically significant increase in the risk of rehospitalization for acute coronary syndrome due to concurrent use of clopidogrel and PPIs in an Asian population with higher prevalence of CYP2C19 intermediate and poor metabolizers. Among all PPIs, only omeprazole was found to be statistically significantly associated with an increased risk of rehospitalization for acute coronary syndrome.

Introduction

Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin has been demonstrated to be able to reduce the recurrent cardiac events and mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [1, 2]. The drugs are usually initiated in hospital and continued after discharge from hospital as recommended by the treatment guidelines for ACS patients [3]. The antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel derives from inhibition of the thiol-containing active metabolite of clopidogrel [4] on the binding of adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP) to the P2Y12 receptor, which prevents activation by ADP of the glycoprotein IIb–IIIa pathway and platelet aggregation [5]. The transformation of clopidogrel to its metabolites includes two consecutive steps [4, 6], and is mainly governed by the cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes, i.e. CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 [6, 7]. Of these, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 are believed to play important roles in various responses of clopidogrel and clinical outcomes in humans [5, 8–10]. Patients who are carriers of CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles may produce less active metabolite of clopidogrel for the same dosage, and thus are exposed to an increased risk of cardiovascular events [10–12]. Consequently, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a warning communication to medical professionals suggesting a dosage adjustment when clopidogrel is used in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers [13]. The FDA also suggested that the concomitant use of omeprazole (or esomeprazole) and clopidogrel should be avoided because of the effects on active metabolite levels of clopidogrel and antiplatelet activity [14].

Owing to the potential risk of bleeding in patients receiving dual antiplatelet therapy [15], concomitant treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) is frequently suggested in patients with a risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding [3, 16]. Such concomitant use of clopidogrel with PPI may be carried over by some patients even after they are discharged from hospital. Proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole and pantoprazole are metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 to different extents [17]. Nevertheless, they are also inhibitors of CYP2C19, with a descending potency of inhibitory effect in the following order: lansoprazole, rabeprazole, omeprazole, esomeprazole and pantoprazole [18, 19]. It is proposed that the inhibitory activities of PPIs on CYP2C19 enzyme may reduce the conversion of clopidogrel to its active metabolite, and therefore weaken the antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel and lead to undesired clinical outcomes for patients. Results from recently published population-based observational studies have supported such concerns [20–22]. Acute coronary syndrome patients who use clopidogrel and PPIs concomitantly have been shown to have a higher risk of cardiovascular-related adverse outcomes, such as death or rehospitalization for ACS [20], reinfarction [22], and rehospitalization for myocardial infarction or coronary stent placement [20], in comparison to those who use clopidogrel alone. However, inconsistent results also exist. Some studies have indicated a slightly increased risk of myocardial infarction-related hospitalization or death but no conclusive evidence regarding the overall cardiovascular risk [23, 24], and others have been shown no association with clopidogrel and PPI concomitanly and clopidogrel alone [25].

The interactions between individual PPIs and clopidogrel have been investigated by surrogate end-points, such as measures of in vitro antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel [26–29]. Co-administration with lansoprazole reduced the clopidogrel inhibitory activity on platelet aggregation after 24 h (n= 24) [26], and combined use of omeprazole and clopidogrel also reduced the antiplatelet response of clopidogrel on day 7 (n= 124) [27]. However, a prospective study showed no significant difference in ADP-induced platelet aggregation among percutaneous coronary intervention patients treated with clopidogrel plus pantoprazole or plus esomeprazole or alone [28]. The impact of individual PPIs on the effectiveness of clopidogrel has not yet been well explored, especially in relation to genetic variations in CYP2C19, as well as in other P450 isoenzymes. Although the prevalence of poor metabolizers of CYP2C19 is estimated to be 0.9–7.7% in Caucasians [30], the prevalence is higher in the Asian population, ranging from 13 to 23% [31]. The prevalence of intermediate metabolizers of CYP2C19 is estimated to be 24.5% in the Caucasian population [32]. Most of the population-based observational studies regarding concomitant use of PPIs with clopidogrel for ACS patients were carried out in Caucasian-abundant populations [20–22]. It is important to study the risks associated with the use of clopidogrel and PPIs in Asians, because the potential effect of PPIs on clopidogrel may be more prominent in this population. In the present study, we examined the impact of concomitant use of PPIs with clopidogrel on the cardiovascular outcomes of patients with ACS using a national medical database that covers 99.7% of the population in Taiwan. In addition, we sought to quantify the effects of individual PPIs on clopidogrel when used concomitantly.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients who were newly hospitalized for ACS between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2007 and were prescribed clopidogrel during the follow-up period. The medical data used to establish this nationwide cohort study were based on patients' data obtained from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) covering the years 2005–2008. The NHIRD includes all claims data from the National Health Insurance (NHI) programme in Taiwan, which has coverage over 99% of the entire Taiwanese population of 23.74 million. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the National Taiwan University Hospital (200911017R).

Study population

We first identified all patients who were hospitalized for ACS between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2007 (n= 111 347). Patients with ACS were defined based on the primary discharge diagnosis code of International Classification of Diseases, ninth Revision (ICD-9-CM Codes), 410.xx, 411xx and 414xx. For each patient, the first hospitalization event due to ACS found in the study period (years 2006–2007) was defined as the index ACS event for the patient and the first hospitalization date of the index event as the index date. Patients who were hospitalized for ACS or had any medical records related to ACS during 2005 and who were hospitalized for ACS within 30 days after the index ACS event were excluded to prevent the counting of rehospitalizations due to acute effects related to the index ACS event. We also excluded patients who were aged less than 18 years old, had no identified discharge date of the index event, and had no recorded clopidogrel prescriptions after discharge from the index ACS event. All the new ACS patients (n= 37 099) during the study period were confirmed to be absent from ACS events at least 1 year before the index ACS event. The study population included ACS patients prescribed clopidogrel, with or without PPIs.

Concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPIs

Patients in the clopidogrel plus PPIs cohort were defined as patients who had clopidogrel and either omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole or rabeprazole concomitantly dispensed on the same day at any time point (more than 1 day) after discharge from the index ACS event and before the occurrence date of the outcome events. In order to calculate the exact days of drug prescriptions, we divided follow-up days ranging from 1 to 1095 days into 1095 single units and coded 0 for no drug use and 1 for drug use on each single day.

Clinical outcomes

The primary clinical outcome was rehospitalization for ACS, while secondary outcomes were rehospitalization for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) with stent, PTCA without stent, and revascularization [PTCA and coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG)] after the discharge date for the index ACS event.

All the patients were followed up, starting at the date of discharge from the index ACS event until the last study date (31 December 2008) or the occurrence of primary or secondary clinical outcome events. Patients were censored at the end of the study duration, last record or rehospitalization with ACS, whichever came first.

Statistical analysis

We used the χ2 test and Student's t-test for the bivariate analysis. The relative risk of concomitant treatment with clopidogrel and PPI compared with clopidogrel alone on the recurrence of cardiovascular events for ACS patients was analysed using a multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model. This Cox proportional hazards regression model included all baseline variables, such as age, sex, diagnosis (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, ischaemic heart disease, ulcer and GI bleeding) and procedures (PTCA, PTCA with stent and CABG) performed at the index ACS event, and the medications [aspirin, β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker, statin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-selective NSAIDs] when discharged from the index event.

Propensity score matching is a method used to control potential confounders by balancing covariates between patient groups with exposure (clopidogrel plus PPIs) and non-exposure (clopidogrel alone) [33–35]. A propensity score, which represents the probability of receiving PPIs, was calculated for each patient by using a logistic regression model with covariates of age, sex, intervention performed at index ACS event (PTCA, PTCA with stent or CABG), ischaemic heart diseases, stroke, other cerebrovascular diseases, heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal diseases, hyperlipidaemia, peripheral vascular diseases, ulcer, GI bleeding and discharge medications (aspirin, β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker or statin). We included the propensity score as a variable in the Cox proportional hazards regression model to adjust for the effect of all the covariates.

The propensity score was also used to identify a new non-exposure (clopidogrel alone) group of patients who had the closest propensity score to the corresponding individuals in the exposure (clopidogrel plus PPIs) group [33, 34]. Patients in the clopidogrel alone group were matched with patients in the clopidogrel plus PPI group based on the propensity score in a 1 : 1 ratio via propensity score nearest-neighbour matching. The randomly selected patients in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group were matched to the patients in the clopidogrel alone group with the closest propensity score within the width of the propensity score of 0.01. This process was repeated until 5173 patients matched by propensity score from the clopidogrel alone group had been found. Patients in the clopidogrel alone group were excluded from the match cohort analysis if there was no match found. The proportional assumption of the Cox proportional hazards was assessed and satisfied by using a graphic method.

Subgroup analysis

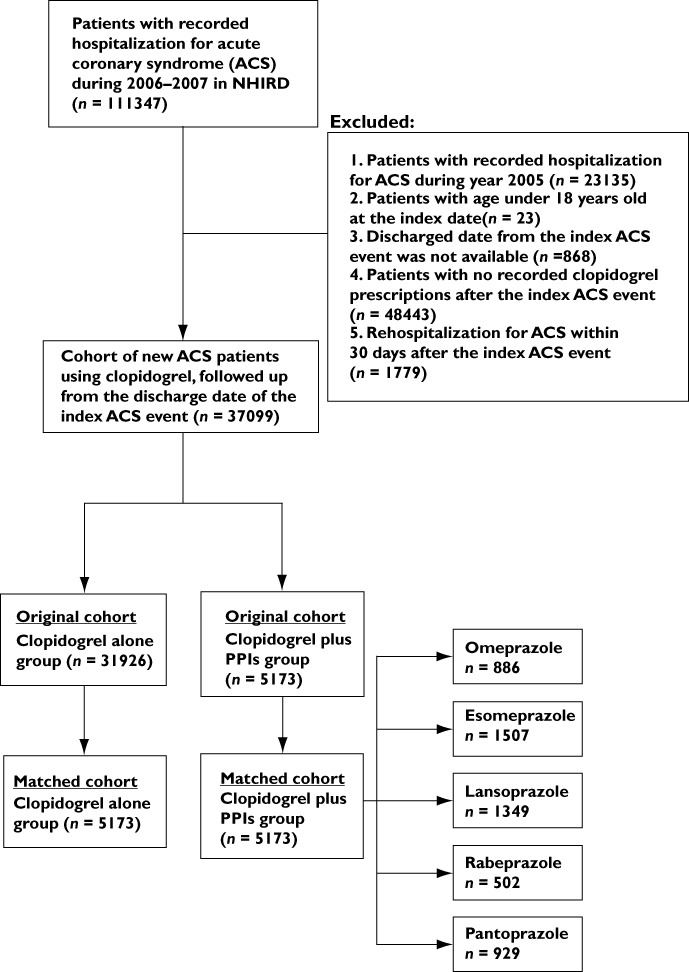

Patients who used only one specific PPI (omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole or rabeprazole) during the follow-up period in the clopidogrel plus PPI group were identified and divided into five subgroups (Figure 1). Patients in each subgroup were compared with patients in the clopidogrel alone group in the matched cohort, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating enrolment of patients for the study cohorts

All tests were two sided, and an α level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 17.0, or SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Sensitivity analyses

In order to explore the robustness of the study results, we performed an analysis for the subgroup of patients with or without previous diagnosis of ulcer, GI bleeding or gastroesophageal reflux disease. We also analysed the cohort by redefining the exposure of clopidogrel plus PPIs as concomitant use more than 7 days after the index ACS event.

Results

Data for 37 099 patients who were hospitalized for an ACS event between 2006 and 2007 and had used clopidogrel after being discharged from the index event were retrieved from NHIRD. These patients represented the original ACS cohort for this study. Among them, 31 926 patients who had used clopidogrel but no PPI during the follow-up period formed the clopidogrel alone group, while 5173 patients who had used clopidogrel and PPI concomitantly for at least 1 day formed the clopidogrel plus PPIs group (Figure 1). The median length of follow up after the index event was 580 days for patients in the original ACS cohort. Baseline characteristics such as age, sex, intervention at the index ACS event and underlying disease conditions showed significant differences between patients in the clopidogrel alone group and in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group in the original cohort. (Table 1) Patients in the clopidogrel alone group were more likely to have undergone PTCA with stent at the index ACS event, and had higher percentages of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease but lower percentages of ulcer and GI bleeding; hence, they had a higher prevalence of aspirin and statin use and a lower prevalence of NSAIDs and COX-2-selective NSAIDs use. The mean total duration of clopidogrel use during the follow-up period for patients in the clopidogrel plus PPI group (235.7 ± 178.0 days) was significantly higher than that of patients in the clopidogrel alone group (128.8 ± 124.2 days; P < 0.001). The mean length of concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPI was 50.8 ± 53.0 days (range 1–553 days).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the original ACS cohort

| Clopidogrel plus PPIs (n= 5173) | Clopidogrel alone (n= 31 926) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years; mean (SD)] | 68.3 (11.4) | 65.4 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| Male sex [n (%)] | 3425 (66.2) | 22 849 (71.6) | <0.001 |

| Intervention at index ACS event [n (%)] | |||

| PTCA | 3090 (59.7) | 23 822 (74.6) | <0.001 |

| PTCA with stent | 2188 (42.3) | 17 933(56.2) | <0.001 |

| PTCA without stent | 902 (17.4) | 5889 (18.4) | 0.082 |

| CABG | 216 (4.2) | 871 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Underlying conditions [n (%)] | |||

| Hypertension | 2800 (54.1) | 17 781 (55.7) | 0.035 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 882 (17.1) | 7679 (24.1) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1816 (35.1) | 10 526 (33.0) | 0.002 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 128 (2.5) | 677 (2.1) | 0.105 |

| Renal disease | 392 (7.6) | 1403 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 674 (13.0) | 3458 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5 (0.1) | 33 (0.1) | 0.889 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 2099 (40.6) | 14 967 (46.9) | <0.001 |

| Ulcer | 935 (18.1) | 858 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 287 (5.5) | 304 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Medication use [n (%)] | |||

| Aspirin | 3582 (69.2) | 28 283 (88.6) | <0.001 |

| β-Blocker | 3727 (72.0) | 23 149 (72.5) | 0.491 |

| ACEI or ARB | 3799 (73.4) | 23 295 (73.0) | 0.477 |

| Statin | 2820 (54.5) | 19 508 (61.1) | <0.001 |

| NSAID | 3946 (76.3) | 22 169 (69.4) | <0.001 |

| COX-2-selective NSAID | 842 (16.3) | 3062 (9.6) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; COX-2-selective NSAID, cyclooxygenase-2-selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; and statin, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor.

We were successful in randomly matching patients in the clopidogrel alone group to patients in the clopidogrel plus PPI group in a 1:1 ratio based on the propensity score for each patient, and this process resulted in 5173 patients in each group in the matched cohort (Figure 1). The characteristics of the final matched clopidogrel alone and clopidogrel plus PPIs cohorts were similar in terms of age, sex, intervention performed at index ACS event, underlying diseases and the medications used (Table 2). Moreover, the mean total lengths of clopidogrel prescriptions for both groups in the matched cohort were nearly the same (233.2 ± 194.3 vs. 235.7 ± 178.0 days). However, the percentages of patients with ulcer and GI bleeding in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group were still higher than those in the matched clopidogrel alone group (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the matched ACS cohort

| Characteristics | Clopidogrel plus PPIs (n= 5173) | Clopidogrel alone (n= 5173) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age [years; mean (SD)] | 68.3 (11.4) | 68.4 (11.9) | 0.546 |

| Male sex [n (%)] | 3425 (66.2) | 3428 (66.3) | 0.896 |

| Intervention at index ACS event [n (%)] | |||

| PTCA | 3090 (59.7) | 3032 (58.6) | 0.246 |

| PTCA with stent | 2188 (42.3) | 2143 (41.4) | 0.370 |

| PTCA without stent | 1076 (16.5) | 1074 (16.5) | 0.962 |

| CABG | 216 (4.2) | 244 (4.7) | 0.182 |

| Underlying conditions [n (%)] | |||

| Hypertension | 2800 (54.1) | 2846 (55.0) | 0.364 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 882 (17.1) | 890 (17.2) | 0.835 |

| Diabetes | 1816 (35.1) | 1796 (34.7) | 0.680 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 128 (2.5) | 140 (2.7) | 0.458 |

| Renal disease | 392 (7.6) | 409 (7.9) | 0.532 |

| Heart failure | 674 (13.0) | 751 (14.5) | 0.028 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 0.739 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 2099 (40.6) | 2114 (40.9) | 0.764 |

| Ulcer | 935 (18.1) | 698 (13.5) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 287 (5.5) | 183 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Medication use [n (%)] | |||

| Aspirin | 3582 (69.2) | 4030 (77.9) | <0.001 |

| β-Blocker | 3727 (72.0) | 3796 (73.4) | 0.128 |

| ACEI or ARB | 3799 (73.4) | 3782 (73.1) | 0.706 |

| Statin | 2820 (54.5) | 3045 (58.9) | <0.001 |

| NSAID | 3946 (76.3) | 3834 (74.1) | 0.011 |

| COX-2-selective NSAID | 842 (16.3) | 677 (13.1) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations are as for Table 1.

In the original cohort, the event rates of rehospitalization due to ACS were 13.9 and 21.4 events per 100 person-years for patients in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group and in the clopidogrel alone group, respectively. For the primary clinical outcome, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups, with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.039 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.976–1.105; P= 0.231] and a propensity score adjusted HR of 1.017 (95% CI, 0.954–1.084; P= 0.603) (Table 3). Likewise, there were no significant differences between the two groups for all the secondary outcomes with the adjusted and propensity score adjusted hazard ratios (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cardiovascular outcomes after discharge from hospitalization for ACS in the original ACS cohort

| Clinical outcome | No. (%) of events Clopidogrel plus PPIs (n= 5173) | Clopidogrel alone (n= 31 926) | Multivariate adjusted HR (95% CI) | Propensity score adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Rehospitalization for ACS | 1228 (23.7) | 10 521 (33.0) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 1.02 (0.95–1.08) |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| Rehospitalization for PTCA | 611 (11.8) | 6291 (19.7) | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) | 0.93 (0.85–1.02) |

| Rehospitalization for PTCA with stent | 345 (6.7) | 3656 (11.5) | 0.94 (0.84–1.06) | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) |

| Rehospitalization for revascularization | 657 (12.7) | 6670 (20.9) | 0.96 (0.88–1.04) | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) |

The Cox proportional hazards regression model included all baseline variables, such as age, sex, diagnosis (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, ischaemic heart disease, ulcer and gastrointestinal bleeding) and procedures (PTCA, PTCA with stent and CABG) performed at the index ACS event, and the medications (aspirin, β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker, statin, NSAIDs and COX-2-selective NSAIDs) when discharged from the index event. Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; and PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

In the propensity score matched cohort, the event rate of rehospitalization due to ACS for clopidogrel with or without PPIs groups were 13.9 and 14.2 events per 100 person-years, respectively. The analyses of the primary and secondary clinical outcomes for patients in matched cohorts (Table 4) produced similar results to those found in the original cohort.

Table 4.

Cardiovascular outcomes after discharge from hospitalization for ACS in the matched ACS cohort

| Clinical outcome | No. (%) of events Clopidogrel plus PPIs (n= 5173) | Clopidogrel alone (n= 5173) | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Multivariate adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||

| Rehospitalization for ACS | 1228 (23.7) | 1274 (24.6) | 0.95 (0.87–1.04) | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) |

| Secondary outcome | ||||

| Rehospitalization for PTCA | 611 (11.8) | 705 (13.6) | 0.85 (0.76–0.95) | 0.94 (0.85–1.05) |

| Rehospitalization for PTCA with stent | 345 (13.3) | 408 (13.0) | 0.84 (0.72–0.97) | 0.93 (0.81–1.08) |

| Rehospitalization for revascularization | 657 (12.7) | 757 (14.6) | 0.85 (0.76–0.95) | 0.95 (0.85–1.05) |

The Cox proportional hazards regression model included all baseline variables, such as age, sex, diagnosis (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, ischaemic heart disease, ulcer and gastrointestinal bleeding) and procedures (PTCA, PTCA with stent and CABG) performed at the index ACS event, and the medications (aspirin, β-blocker, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker, statin, NSAIDs and COX-2-selective NSAIDs) when discharged from the index event. Abbreviations are as for Table 3.

We further divided the patients in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group into five subgroups according to the PPI used for each patient (Figure 1). Patients who had used more than one type of PPI were not included in any subgroup. Patients in each subgroup were respectively compared with patients in the matched clopidogrel alone group. The characteristics of subgroups in the final matched clopidogrel alone cohort and the clopidogrel plus PPIs cohorts were similar in terms of age, sex, intervention performed at index ACS event, underlying diseases and the medications used (Table 5). However, the percentages of use of aspirin and statin in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group were lower than those in the matched clopidogrel alone group within the omeprazole and lansoprazole subgroups (Table 5). The percentages of patients with ulcer and GI bleeding in the clopidogrel plus PPIs group were higher than those in the matched clopidogrel alone group within the esomeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole subgroups (Table 5). The mean length of concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPI for patients in the clopidogrel plus omeprazole subgroup (27.9 ± 39.0 days) was significantly shorter than that for patients in other PPI subgroups (Table 5). Clinical outcome analysis for these PPI subgroups indicated that only omeprazole was associated with a statistically significant increase in the risk for rehospitalization due to ACS, with an adjusted HR of 1.226 (95% CI, 1.066–1.410), but not in the risks of rehospitalization for PTCA, PTCA with stent and revascularization. The other four PPIs did not show any significant increase in the risk of the observed outcomes, although the results of rabeprazole were greater than one and were slightly higher than those of the others.

Table 5.

Cardiovascular outcomes following ACS based on the use of individual PPIs in the matched ACS cohort

| Clopidogrel + omeprazole (n= 886) | Clopidogrel + esomeprazole (n= 1507) | Clopidogrel + lansoprazole (n= 1349) | Clopidogrel + rabeprazole (n= 502) | Clopidogrel + pantoprazole (n= 929) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of concomitant use [days; mean ± SD (range)] | 27.86 ± 39.01 (1–298) | 61.96 ± 59.60 (1–542) | 50.66 ± 47.09 (1–478) | 55.09 ± 49.80 (1–337) | 52.20 ± 56.34 (1–553) |

| Primary outcome [adjusted HR (95% CI)]* | |||||

| Rehospitalization for ACS | 1.226 (1.066–1.410) | 1.005 (0.892–1.133) | 0.964 (0.849–1.095) | 1.182 (0.987–1.416) | 1.013 (0.873–1.176) |

| Secondary outcome [adjusted HR (95% CI)]* | |||||

| Rehospitalization for PTCA | 1.090 (0.898–1.300) | 0.849 (0.714–1.010) | 0.964 (0.849–1.095) | 1.176 (0.924–1.496) | 0.885 (0.715–1.097) |

| Rehospitalization for PTCA with stent | 1.052 (0.807–1.372) | 0.864 (0.689–1.083) | 0.788 (0.617–1.008) | 1.188 (0.866–1.630) | 0.989 (0.759–1.289) |

| Rehospitalization for revascularization | 1.126 (0.933–1.359) | 0.845 (0.715–0.998) | 0.910 (0.768–1.078) | 1.143 (0.903–1.447) | 0.894 (0.728–1.098) |

Abbreviations are as for Table 3.

Each subgroup was compared with the clopidogrel alone group in the matched cohort.

We split the matched cohort into patients with or without previous diagnosis of ulcer, GI bleeding or gastroesophageal reflux disease and yielded results similar to those of the primary analysis. We also found similar results when we redefined the exposure of clopidogrel plus PPIs as concomitant use for more than 7 days after the index ACS event. Regardless of whether we included the propensity score as a variable in the models in the original cohort or whether we identified a matched cohort based on propensity score to run the analysis, we observed similar results compared with the multivariable regression models including all of the covariates used in this study.

Discussion

The potential association of concomitant use of clopidogrel and PPI and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with ACS has raised great concerns [20–22, 36]. However, the findings in the literature are not consistent [19, 23, 24, 37]. To our knowledge, this is the first large cohort study in an Asian population concerning the interaction between clopidogrel and PPI in ACS patients. It adds to the literature because it covered a nationwide population and had a follow-up period of >17 months on average and at least 1 year for each patient. We applied both basic statistical methods and an advanced propensity score matching technique to control for potential confounders. Moreover, we were able to compare all PPIs currently available on the market (omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole) with regard to their influence on the risk of subsequent ACS events when they were used concurrently with clopidogrel. Previously published retrospective cohort studies were carried out mainly in Caucasian populations and tended to have one predominant PPI (>50%) in use, such as omeprazole [21, 23], pantoprazole [23, 24] or lansoprazole [24].

Our analyses from the original cohort and the propensity score matched cohort indicated no statistically significant increase in the risk of rehospitalization for ACS due to concurrent use of clopidogrel and PPIs. Omeprazole is the only PPI that demonstrated a significant association with the increased risk of rehospitalization for ACS when it was used concomitantly with clopidogrel. Given that this is the only statistically significant result out of the many subgroup analyses of several outcomes, the possibility that this is a chance finding cannot be ruled out. Omeprazole did not have a negative effect on cardiovascular outcome in the Clopidogrel and the Optimization of Gastrointestinal Events (COGENT) study, but there were several limitations of that study, such as premature termination of the study, patients with an indication for a PPI being excluded, and the study being underpowered [38]. We found similar results with patients who had hospitalization for ACS within 30 days after the index ACS event. The adjusted HRs were as follows: rehospitalization for ACS, 1.06 (95% CI, 0.87–1.29); rehospitalization for PTCA, 0.99 (95% CI, 0.75–1.31); rehospitalization for PTCA with stent, 1.11 (95% CI, 0.80–1.54); and rehospitalization for revascularization, 0.95 (95% CI, 0.74–1.23). In order to explore the robustness of the study results, we performed subgroup analysis in the matched cohort for the patients with or without previous diagnosis of ulcer, GI bleeding and heart failure or use of aspirin, and obtained results similar to those of the primary analysis. We also included the days of PPIs use as a time-varying covariate in the COX regression analysis. The results were similar with the primary analysis.

Our findings did not indicate an increased risk of rehospitalization for PTCA (with or without stent) or revascularization when ACS patients were treated with clopidogrel plus PPIs (Table 4). These findings are consistent with several previous retrospective cohort studies [20, 21]. Two studies conducted by using a progressive confounders control technique showed no statistically significant risk of interactions between clopidogrel and PPIs [23, 24]. Another study, which involved patients hospitalized with ACS, showed that concurrent PPI users (predominant use of omeprazole) had a greater risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes than users of clopidogrel alone [21].

The extent of inhibitory activity of PPIs on CYP2C19 can be one of the important factors affecting outcome. The correlation between antiplatelet activity and the clinical protection afforded by clopidogrel is still not well established.

The potential risk of rehospitalization for ACS was statistically significantly associated with concomitant use of omeprazole, but not with use of esomeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole or lansoprazole, which indicates that there may not be a class effect. This may due to the fact that omeprazole is able markedly to reduce the antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel, as indicated in a randomized study [27]. One in vitro study has shown that pantoprazole has lower inhibition potency on CYP2C19 than do lansoprazole, omeprazole and esomeprazole, and thus less potential to affect clopidogrel activity than do other PPIs [18]. The inhibition potencies of individual PPIs on CYP2C19 enzyme are different; consequently, the extent of interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs in terms of antiplatelet activity may be different as well [18, 19]. In combination with a CYP2C19 inhibitor, intermediate metabolizers could become poor metabolizers [39].

By measuring the platelet reactivity index, pantoprazole and esomeprazole were demonstrated not to be associated with an impaired response to clopidogrel [28]. However, simultaneous administration of omeprazole and pantoprazole decreased the exposure of the active metabolite of clopidogrel by 45 (P < 0.001) and 20% (P < 0.001), respectively, after a clopidogrel loading dose [40]. Drug–drug interaction exists between clopidogrel and omeprazole but not pantoprazole in terms of maximal platelet aggregation and vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein phosphorylation platelet reactivity index [40]. A significant reduction in the effect of clopidogrel in terms of mean P2Y12 reaction units was also observed when patients were initiated with omeprazole, but not with pantoprazole [41]. Omeprazole, but not lansoprazole or pantoprazole, was identified as an irreversible metabolism-dependent inhibitor of CYP2C19. This may explain why lansoprazole, a more potent direct-acting inhibitor of CYP2C19 in vitro than omeprazole, does not cause clinically significant inhibition of CYP2C19, whereas omeprazole does [42]. However, such potential drug–drug interaction may or may not reflect any clinical outcomes for ACS patients. The correlation between such potential drug–drug interactions and adverse clinical outcomes has not yet been established. Our findings are consistent with some, but not all, previous laboratory and mechanistic studies.

The CYP2C19 poor metabolizers have been demonstrated to exhibit less antiplatelet activity when they were exposed to the same clopidogrel regimen as the other healthy volunteers. It is speculated that the clopidogrel activity affected by PPI might be more pronounced in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers than in others. The opportunity to observe undesired cardiovascular outcomes for ACS patients in an area having a higher prevalence of CYP2C19 poor metabolizers, such as in Asia, may be higher [31]. An observational study showed that patients with two variant alleles of ABCB1 (a gene modulating clopidogrel absorption) had a higher HR (1.72; 95% CI 1.20–2.47) of cardiovascular events at 1 year than those with the ABCB1 wild-type genotype. Patients carrying any two CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles had a higher HR (1.98; 95% CI 1.10–3.58) than patients with none [43]. We did not have the patient's information regarding the polymorphism of CYP2C19 (the gene modulating clopidogrel metabolic activation) or ABCB1 (the gene modulating clopidogrel absorption). Competition on inhibition of the CYP2C19 enzyme is one of the putative mechanisms of interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs. This raises a question regarding the net impact of competition on inhibition of the CYP2C19 enzyme by PPIs together with the patient's polymorphisms of genes on the outcomes of a drug–drug interaction between clopidogrel and PPIs. One study shows that CYP2C19*2 carriers have a much higher platelet aggregation while using omeprazole than patients with the wild-type genotype using omeprazole [39]. In combination with a CYP2C19 inhibitor, they could become poor metabolizers.

Additional research is necessary to evaluate the combined effect of the CYP2C19 metabolism competition and patients' polymorphisms of genes on the adverse outcomes associated with clopidogrel used concomitantly with PPIs and the specific effects of individual PPIs.

There are limitations in the present study. The information with regard to patient adherence or self-paid medications is not available. This may lead to misclassification and probably biases the results towards a null effect, which would not have changed the clinically significant result regarding the increased risk of rehospitalization for ACS associated with concurrent clopidogrel and omeprazole use. Death records were not available in the national health insurance research database, but we have captured important clinical outcomes of rehospitalization of ACS, and PTCA with or without stent for ACS patients. All the PPIs are prescription drugs in Taiwan, but omeprazole is an over-the-counter drug in the USA. The possibility of misclassification of exposure to PPIs may be small in this study. To our knowledge, this is the study with the largest sample size to explore the possible risk of clopidogrel–PPIs or clopidogrel with five individual PPI (omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole or lansoprazole) interactions in the cohort with higher prevalence of CYP2C19 poor metabolizers in Asia. Our study indicated no statistically significant increase in the risk of rehospitalization for ACS due to concurrent use of clopidogrel and PPIs. Among all PPIs, only omeprazole was found to be statistically significantly associated with potential risk of rehospitalization for ACS.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored in part by a research grant from the Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health, Taiwan (DOH99-FDA-41005).

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, 3rd, Fry ET, DeLago A, Wilmer C, Topol EJ. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2411–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatt DL, Scheiman J, Abraham NS, Antman EM, Chan FK, Furberg CD, Johnson DA, Mahaffey KW, Quigley EM. ACCF/ACG/AHA 2008 expert consensus document on reducing the gastrointestinal risks of antiplatelet therapy and NSAID use: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation. 2008;118:1894–909. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savi P, Pereillo JM, Uzabiaga MF, Combalbert J, Picard C, Maffrand JP, Pascal M, Herbert JM. Identification and biological activity of the active metabolite of clopidogrel. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:891–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen T, Frishman WH, Nawarskas J, Lerner RG. Variability of response to clopidogrel: possible mechanisms and clinical implications. Cardiol Rev. 2006;14:136–42. doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000188033.11188.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagihara K, Kazui M, Kurihara A, Yoshiike M, Honda K, Okazaki O, Farid NA, Ikeda T. A possible mechanism for the differences in efficiency and variability of active metabolite formation from thienopyridine antiplatelet agents, prasugrel and clopidogrel. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2145–52. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.028498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kazui M, Nishiya Y, Ishizuka T, Hagihara K, Farid NA, Okazaki O, Ikeda T, Kurihara A. Identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the two oxidative steps in the bioactivation of clopidogrel to its pharmacologically active metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:92–9. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fontana P, Hulot JS, De Moerloose P, Gaussem P. Influence of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 gene polymorphisms on clopidogrel responsiveness in healthy subjects. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:2153–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau WC, Gurbel PA, Watkins PB, Neer CJ, Hopp AS, Carville DG, Guyer KE, Tait AR, Bates ER. Contribution of hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolic activity to the phenomenon of clopidogrel resistance. Circulation. 2004;109:166–71. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112378.09325.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias W, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Meneveau N, Steg PG, Ferrieres J, Danchin N, Becquemont L. ST-Elevation tFRoA, Non-ST-Elevation myocardial infarction investigators. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:363–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(FDA) TUSFaDA. FDA Drug safety communication: reduced effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in patients who are poor metabolizers of the drug. 2010. March 12, 2010 Edition: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

- 13.(FDA) TUSFaDA. FDA drug safety communication: reduced effectiveness of Plavix (clopidogrel) in patients who are poor metabolizers of the drug. 2010.

- 14.(FDA) TUSFaDA. Information for healthcare professionals: update to the labeling of Clopidogrel Bisulfate (marketed as Plavix) to alert healthcare professionals about a drug interaction with omeprazole (marketed as Prilosec and Prilosec OTC) 2010.

- 15.Aronow HD, Steinhubl SR, Brennan DM, Berger PB, Topol EJ. Bleeding risk associated with 1 year of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial. Am Heart J. 2009;157:369–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreiner GC, Laine L, Murphy SA, Cannon CP. Evaluation of proton pump inhibitor use in patients with acute coronary syndromes based on risk factors for gastrointestinal bleed. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6:169–72. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e318159921e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khalique SC, Cheng-Lai A. Drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:198–200. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181a857ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li XQ, Andersson TB, Ahlstrom M, Weidolf L. Comparison of inhibitory effects of the proton pump-inhibiting drugs omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole on human cytochrome P450 activities. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004;32:821–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu TJ, Jackevicius CA. Drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30:275–89. doi: 10.1592/phco.30.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockl KM, Le L, Zakharyan A, Harada AS, Solow BK, Addiego JE, Ramsey S. Risk of rehospitalization for patients using clopidogrel with a proton pump inhibitor. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:704–10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, Rumsfeld JS. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301:937–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, Szmitko PE, Austin PC, Tu JV, Henry DA, Kopp A, Mamdani MM. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180:713–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rassen JA, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Schneeweiss S. Cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in patients using clopidogrel with proton pump inhibitors after percutaneous coronary intervention or acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2009;120:2322–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, Chung CP, Smalley WE, Hall K, Daugherty JR, Kaltenbach LA, Stein CM. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:337–45. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, Michelson AD, Hautvast RW, Ver Lee PN, Close SL, Shen L, Mega JL, Sabatine MS, Wiviott SD. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Small DS, Farid NA, Payne CD, Weerakkody GJ, Li YG, Brandt JT, Salazar DE, Winters KJ. Effects of the proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and clopidogrel. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48:475–84. doi: 10.1177/0091270008315310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, Mansourati J, Mottier D, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siller-Matula JM, Spiel AO, Lang IM, Kreiner G, Christ G, Jilma B. Effects of pantoprazole and esomeprazole on platelet inhibition by clopidogrel. Am Heart J. 2009;157:148. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.09.017. e1–e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun KH, Rhee SJ, Park HY, Yoo NJ, Kim NH, Oh SK, Jeong JW. Effects of omeprazole on the antiplatelet activity of clopidogrel. Int Heart J. 2010;51:13–6. doi: 10.1536/ihj.51.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie HG, Stein CM, Kim RB, Wilkinson GR, Flockhart DA, Wood AJ. Allelic, genotypic and phenotypic distributions of S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylase (CYP2C19) in healthy Caucasian populations of European descent throughout the world. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneko A, Lum JK, Yaviong L, Takahashi N, Ishizaki T, Bertilsson L, Kobayakawa T, Bjorkman A. High and variable frequencies of CYP2C19 mutations: medical consequences of poor drug metabolism in Vanuatu and other Pacific islands. Pharmacogenetics. 1999;9:581–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elmaagacli AH, Koldehoff M, Steckel NK, Trenschel R, Ottinger H, Beelen DW. Cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism is associated with an increased treatment-related mortality in patients undergoing allogeneic transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:659–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D'Agostino RB., Jr Propensity scores in cardiovascular research. Circulation. 2007;115:2340–3. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.594952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:757–63. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Sturmer T. Indications for propensity scores and review of their use in pharmacoepidemiology. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;98:253–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pezalla E, Day D, Pulliadath I. Initial assessment of clinical impact of a drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1038–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.053. author reply 39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norgard NB, Mathews KD, Wall GC. Drug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and the proton pump inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1266–74. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, Cohen M, Lanas A, Schnitzer TJ, Shook TL, Lapuerta P, Goldsmith MA, Laine L, Scirica BM, Murphy SA, Cannon CP. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sibbing D, Gebhard D, Koch W, Braun S, Stegherr J, Morath T, Von Beckerath N, Mehilli J, Schomig A, Schuster T, Kastrati A. Isolated and interactive impact of common CYP2C19 genetic variants on the antiplatelet effect of chronic clopidogrel therapy. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:1685–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Angiolillo DJ, Gibson CM, Cheng S, Ollier C, Nicolas O, Bergougnan L, Perrin L, LaCreta FP, Hurbin F, Dubar M. Differential effects of omeprazole and pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel in healthy subjects: randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover comparison studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:65–74. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fontes-Carvalho R, Albuquerque A, Araujo C, Pimentel-Nunes P, Ribeiro VG. Omeprazole, but not pantoprazole, reduces the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel: a randomized clinical crossover trial in patients after myocardial infarction evaluating the clopidogrel-PPIs drug interaction. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:396–404. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283460110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogilvie BW, Yerino P, Kazmi F, Buckley DB, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Paris BL, Toren P, Parkinson A. The Proton Pump Inhibitor, Omeprazole, but not Lansoprazole or Pantoprazole, is a Metabolism-Dependent Inhibitor of CYP2C19: implications for Coadministration with Clopidogrel. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011;39:2020–33. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.041293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Meneveau N, Steg PG, Ferrieres J, Danchin N, Becquemont L. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:363–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]