Abstract

We conducted a study designed to evaluate the efficacy and feasibility of a multilevel self-management intervention to improve nutritional intake in a group of older adults receiving Medicare home health services who were at especially high risk for experiencing undernutrition. The Behavioral Nutrition Intervention for Community Elders (B-NICE) trial used a prospective randomized controlled design to determine whether individually tailored counseling focused on social and behavioral aspects of eating resulted in increased caloric intake and improved nutrition-related health outcomes in a high-risk population of older adults. The study was guided by the theoretical approaches of the Ecological Model and Social Cognitive Theory. The development and implementation of the B-NICE protocol, including the theoretical framework, methodology, specific elements of the behavioral intervention, and assurances of the treatment fidelity, as well as the health policy implications of the trial results, are presented in this article.

Keywords: aging, care transitions, community health, home health care, nutrition, randomized controlled trial, self management

INTRODUCTION

The Behavioral Nutrition Intervention for Community Elders (B-NICE) was designed to maintain or increase energy intake (depending on baseline body mass index) in older adults who were receiving Medicare home health services in order to prevent unintentional weight loss during recovery from illness. Undernutrition (defined as poor nutritional intake, low anthropometric measurements, unintentional weight loss, and abnormal biochemical markers) is a common problem in older adults, especially those receiving home health services; many of these individuals have experienced a recent hospitalization and are dealing with multiple comorbidities (1–3). Yet, interventions targeted at addressing undernutrition in older adults, particularly homebound older adults, are especially sparse. Most have included invasive or more costly one-dimensional approaches, such as parenteral and enteral nutrition support, appetite stimulation agents, and dietary supplements (which have often proven ineffective) (3, 4). Furthermore, these studies have generally included participants who were more seriously malnourished than those who were enrolled in the present trial. We included older adults who did not yet require these more drastic measures. Additionally, because we wished to develop an intervention that could be maintained over time, we avoided recommending any measures that may not have been well-tolerated or that might be costly to the study participants.

Studies of noninvasive and inexpensive interventions designed to increase caloric intake in older adults residing in nursing home have found that (1) complying with participants’ preferences, (2) enhancing the flavor of food, (3) modifying the eating environment, (4) offering a variety of foods, and (5) increasing attention, social stimulation, and encouragement all improved intake and, in some instances, promoted weight gain and improved other health outcomes (5–11). These common-sense approaches have not been applied in the community setting where many older adults may be at risk for institutionalization because of undernutrition.

B-NICE is especially timely in reference to current health policy: (1) it is the first evidence-based intervention in the area of undernutrition and self-care education delivered in the home; (2) its focus is on health outcomes as they relate to nutritional therapy; (3) there is a recognition that the Registered Dietitian, particularly one trained in self-management education techniques, may be the health care professional best-suited to deliver such a nutritional intervention; and (4) the focus is on transitions of care of older individuals from the hospital to the community. The development and implementation of the B-NICE protocol, including the theoretical framework, the methodology, the specific elements of the behavioral intervention, and assurances of treatment fidelity, as well as the health policy implications of the trial results, are presented in this article. The outcomes of the trial will be the focus of future publications.

THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES

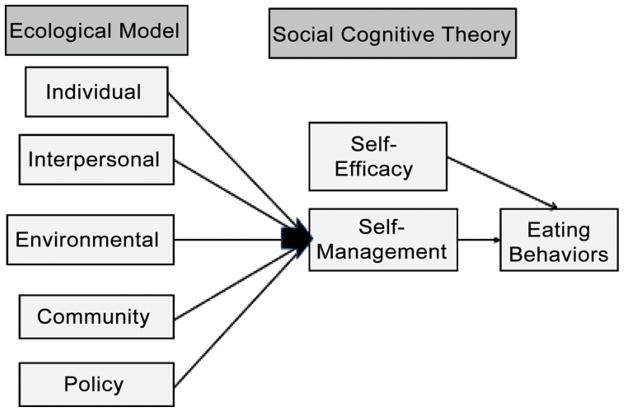

The B-NICE study was guided by the theoretical approaches of the Ecological Model (EM) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) (Figure 1). These theories are especially useful in combination with one another because they emphasize the reciprocal relationship that exists between individual behavior and the social environment; moreover, both have been recommended as particularly well-suited for addressing the problem of poor nutritional health in home-bound older adults (12, 13). Specifically, we used an EM in designing particular components of the intervention and SCT in developing the manner in which the intervention was implemented.

FIGURE 1.

The Behavioral Nutrition Intervention for Community Elders trial was based on a theoretically derived model for a nutrition intervention and targeted older adults who were receiving Medicare home health services and were already malnourished or at high risk for undernutrition. (Color figure available online.)

Ecological Model

The EM is a comprehensive multilevel approach that incorporates concepts from many theoretical perspectives that are key in specifying conditions needing to be changed in order to effect desired health actions (14). The levels of influence that affect behavior in the EM include individual (knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs), interpersonal (primary group influence and support), institutional (norms or structures—in this case in the home), community (formal and informal networks of support), and public policy factors (government intervention) (14–17). This is particularly important for the design of the B-NICE trial approach because eating behaviors are simultaneously influenced by many different micro- and macrolevel factors that contribute to poor eating behaviors and outcomes. Based on our own work and that of others, we focused specifically on encouraging participants to (1) participate in the planning of meals and to consume foods that are familiar and well-liked (individual-level); (2) eat meals with others present and at the table (if possible) (interpersonal); (3) modify foods (e.g., eat items as finger food) and/or modify environment (e.g., have food served within easy access and/or minimize noise and distractions during meals) (institutional); (4) use community food programs (e.g., those provided by neighborhood or religious organizations) (community); and (5) use government programs (e.g., home-delivered meal services, Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program [formerly food stamps], food commodity programs) (public policy) (18, 19). The applicability of the EM to nutrition and aging has been described extensively by Locher and Sharkey (20).

Social Cognitive Theory

The individual level of influence affecting behavior in the EM includes knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs—these are central to an individual’s capability to change and are key tenets of SCT (21). As we discovered in our preliminary studies, individuals have considerable variability in their food preferences, barriers to eating, and psychosocial support for effecting health behavior change. A traditional model of educating individuals to make health behavior change(s) places the clinician in the expert role and the participant in the role of receiving information and making the change(s) (22). The problem with this one-way educational approach is that it does not sufficiently capitalize on participants’ unique expertise in terms of their knowledge of their own preferences, barriers, strengths, and abilities to problem solve and does not take advantage of their abilities to identify goals that they are motivated to work on in their own environment. We have found gender and ethnic differences in the social and environmental factors that affect nutritional health and individual differences in food preferences and barriers to adequate nutrition, including caregiver support. Because of these important differences and our interest in empowering participants and their caregivers to be actively involved in the change process, we determined that the addition of several components of SCT would assist in developing and delivering the B-NICE intervention, particularly in regard to self-management education.

First, SCT emphasizes reciprocal determinism such that behavior is understood to be a result of interaction that occurs between an individual and his or her environment. The B-NICE protocol engaged the individual and his or her caregiver(s) to make changes in their interaction or in the home environment, if necessary. Second, a major assumption underlying SCT is that individuals possess the behavioral capability to make changes if they have the knowledge and skills to do so. B-NICE interventionists worked with study participants to identify what capabilities they possessed and what resources were available to them. Third, SCT emphasizes that an individual’s expectations regarding the outcome of his or her behavior will influence that behavior. Participants in the B-NICE trial were asked to consider what the results of various courses of action might be. Fourth, self-efficacy, a major component of SCT, is the belief that one has the capability to organize and execute courses of actions necessary to achieve some goal (23, 24). An individual must possess confidence that he or she will be able to make changes in order for action to be taken. Self-efficacy theory underlies self-management education, which emphasizes that increased confidence in the ability to make change influences change above and beyond information and technical skills (i.e., information alone is often not sufficient for the complex and difficult changes associated with chronic conditions) (25). Self-management education also emphasizes collaborative care, problem solving, and short-term action plans. Each of these allows for opportunities to enhance individuals’ confidence in their own ability to take the next steps toward change (22). Fifth, SCT emphasizes reinforcement. B-NICE interventionists provided encouragement, support, and praise to increase an individual participant’s likelihood of following through with behavioral changes.

METHODOLOGY

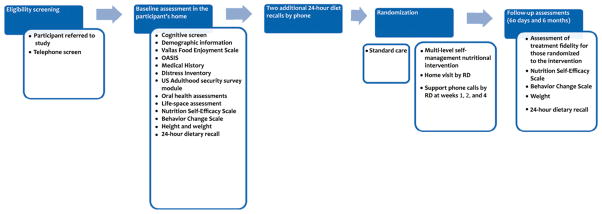

A standardized protocol was employed to implement the B-NICE. The following sections describe key elements relevant for a comprehensive understanding of delivery of this intervention (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow of B-NICE study relevant to delivery and assessment of the intervention. (Color figure available online.)

Eligibility Screening/Baseline Assessment

Initial Eligibility Screening was conducted by a Research Assistant (RA) first over the phone, and later in the participant’s home. The RA reviewed the study protocol in detail with the potential participant and conducted an eligibility screen to verify that the individual met those inclusion and exclusion criteria that could be established over the phone. The RA confirmed that the patient was still interested in participating in the study. If so, a time was scheduled for the RA to go to the participant’s home. While in the home, the RA obtained written informed consent from the participant to agree to participate in the study. Next, the participant was administered a Folstein’s Mini-Mental State Exam. This test of global cognitive function was administered in order to exclude those with significant cognitive impairment (MMSE <15/range 0–30), since it was unlikely that those persons could benefit from participation in an intervention that relied heavily on self-management behaviors (26, 27).

If the participant was not excluded based on cognitive function, a comprehensive Baseline Assessment was then obtained. This assessment was used to (1) further assess eligibility status, (2) guide the multilevel self-management nutritional intervention, and (3) gather outcome measures. The choice of assessment tools was carefully selected so as to include factors found to be associated with nutritional intake in our studies and those of others and to emphasize those factors recommended by the IOM Committee on Nutrition Services for Medicare Beneficiaries to be used to evaluate community-dwelling older adults (3). The assessment included social, psychological, economic, medical, functional, and oral health factors that are related to nutritional intake; a copy of the full assessment is available on request from the first author.

The interview portion of the assessment began with the Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale, followed by questions related to social support, caregiving, and food issues from the Outcome and Assessment Information (OASIS) (28), a Medical History from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Study of Aging, reason(s) for home health admission, the Distress Inventory for depression and anxiety (29), a modification of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Adult Food Security Survey Module (asked only of the participant—not all adults in household) (30), questions regarding physical resources, a Medication Inventory, an Oral Health Assessment based on the Geriatric Oral Health Index and the Leake Index of Chewing Ability (31, 32), the UAB Study of Aging Life-Space Assessment (33), the Nutrition Self-Efficacy Scale (34) developed by Schwarzer and Renner to assess self-efficacy specifically for nutritional changes, and the Behavior Change Scale (35) to assess goal-setting and relapse prevention behavior. Self-reported health service utilization within the past 6 months for the baseline interview and since the last interview for subsequent interviews was also recorded. Demographic data and contact information of two close relatives or friends (in order to maintain long-term follow-up) was collected. The Baseline Assessment also included the measurement of weight and height. For those unable to stand, we relied on self-reported height. While still in the home, the RA concluded the Baseline Assessment with a 24-hr dietary recall interview.

Subsequent to the Baseline Assessment, participants were called over the next 2 weeks to obtain two additional dietary recalls. The three recalls were aggregated to obtain an average daily caloric intake. This mean energy intake value was used in determining final eligibility; participants meeting all other eligibility criteria who were consuming insufficient calories to maintain their current body weight or who were underweight (based on a calculation of their daily energy expenditure based on current height, weight, age, activity level, and gender) were enrolled in the study. The formula for defining underweight is described in-depth elsewhere (36, 37). Use of three 24-hr dietary recalls is a well-established and widely used methodology for collecting data on usual eating behavior; and the methods have been successfully used and psychometrically evaluated in homebound older adults (13, 38, 39).

Randomization

Once enrolled, participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups: Standard Care or a Multilevel Self-Management Nutritional Intervention. In order to approximate as close as possible to the real world setting, the intervention phase of the study lasted 60 days. This is the amount of time that a patient receiving Medicare is eligible to receive home health services wherein each 60-day period is defined as a home health episode. This is also a reasonable and standard amount of time for a behavioral intervention to be in place and have demonstrable effects. Thus, the 60-day period is pragmatically and theoretically derived and appropriate.

Multilevel Self-Management Nutritional Intervention

The multicomponent behavioral intervention was based on an extensive review of the literature, the Ecological Model, Social Cognitive Theory, and our own preliminary findings and clinical practice (Table 1). The precise intervention was tailored to the individual participant after a careful review of the participant’s Baseline Assessment and three 24-hr dietary recalls. Collection of dietary recalls used standards consistent with those of the University of Minnesota (where all the RAs received formal training), including standardized probing questions, two-dimensional food models to estimate portion size, and a multiple-pass methodology. Dietary recall data were entered into and analyzed using the Minnesota Nutrition Data System, a nutrition analysis program that computes detailed dietary information, including calories per meal (NDSR, Minneapolis, MN) (40). An emphasis was placed on a participant’s perceived barriers, preferences, motivation, and confidence in his or her ability to make changes. The RA used a checklist to review these for each participant for each eating behavior to be targeted. This checklist and a summary of patient data were given to the Interventionist (an RD) and used as a guide to develop the individually tailored intervention for each participant. Attention was given to personal food preferences and habits, meal patterns, resources available for meal preparation, needs for assistance with eating, and social support. Attention also was given to medical conditions, especially those requiring a special diet (e.g., diabetes, congestive heart failure, renal disease, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). An individualized nutritional intervention was created for (and with) each participant in consultation with the other members of the investigative team, particularly the geriatrician (CSR) and RDs, and the participant’s caregiver(s) as needed.

TABLE 1.

Elements of the Ecological Model, the Specific Interventions, and the Criteria Supporting the Interventions Used in the Multilevel Self-Management Behavioral Nutrition Intervention Trial

| Eating Behavior | Data source for evaluation/ (Criteria for Intervention) | Specific intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Level | ||

| Eat familiar, favorite foods that are calorie dense | 3 dietary recalls & Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale for favorite foods that are calorie dense (If participant reports low energy intake &/or poor appetite) | Encourage participant to eat calorie-dense favorite foods & discuss examples. |

| Active involvement with meals (e.g., planning menu, making shopping list, etc.) | Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale (If participant reports not eating due to non-involvement in meal planning) | Suggest caregiver consider participant’s preferences. Provide list of favorite foods & dislikes which are reported by participant. |

| Enhance the flavor of foods | Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale (If participant reports low intake due to sensory deficits) | Encourage use of flavor enhancements & give list of examples based on food preferences. |

| Moderate therapeutic diets | Medical diagnosis, medication inventory, & Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale (If 1 or more special dietary restrictions are prescribed) | Recommend moderation of special diets (with medical consult). Specific instructions will be given to participant/caregiver & communicated to medical care team. |

| Take a multivitamin mineral supplement | 3 dietary recalls (If low food intake) | Recommend a multivitamin/mineral supplement & provide list of example brands. |

| Interpersonal Level | ||

| Eat with family or friends | 3 dietary recalls (If > 1 meal/day eaten alone) | Encourage participant to eat with others more often. |

| Eat at table with others present | 3 dietary recalls (If > 1 meal/day eaten not at table & physically able) | Encourage participant to eat with others at table. |

| Use consistent & familiar feeder (if needs assistance feeding) | OASIS questionnaire (If receives assistance, but not consistent feeder) | Encourage use of consistent feeder. Provide feeder with verbal and written instructions on appropriate techniques. |

| Institutional Level | ||

| Eat in calm eating environment | Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale & observation of environment (If participant reports meals are disturbed by environment) | Suggest environmental changes to enhance meal time (e.g., reduce noise levels & minimize distractions & interruptions). Also, avoid confusing or blaming statements, pressure, & conflict during meal time. |

| Place foods within easy physical access | Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale, medical diagnosis, & OASIS questionnaire (If participant reports being chair- or bed-bound affects their ability to feed self) | Advise caregivers & participants to have food close to where they spend their time, within easy reach. Also encourage participant to ask or ring bell if hungry or thirsty. |

| Place food within visual range | Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale & OASIS questionnaire (If participant has visual impairments & reports difficulty with feeding self) | Recommend caregiver & participant place food close enough to see & provide good lighting. |

| Eat food in small portions | 3 dietary recalls (If low food intake) | Recommend smaller, more frequent meals. |

| Eat finger foods or make modifications to food | Vailas Food Enjoyment Scale & OASIS questionnaire (If participant reports difficulty with feeding self) | Encourage caregiver & participant to use finger foods & make modifications to other foods. Provide verbal & written examples. |

| Community Level | ||

| Utilize non-governmental community resources | OASIS & HSU questionnaires (If does not use available resources but could benefit from them) | Provide list of available resources & encourage use (e.g., religious or neighborhood organizations). |

| Policy Level | ||

| Utilize governmental food & nutrition services that have needs based criteria | OASIS, HSU, & USDA questionnaires (If participant is eligible but not using food & nutrition services) | Provide information on available resources & encourage use (e.g., Food Stamps, home-delivered meals, food commodities, etc.). |

Note. OASIS: Outcomes and Assessment Information Set required for use by Medicare-certified home health agencies designed to measure outcomes; HSU: Health Services Utilization questionnaire; USDA: United States Department of Agriculture; Food stamps: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

The nutrition intervention consisted of a multilevel self-management program that was designed by the research team and administered by one of the RDs (AE, JL, and LN). An RD was chosen to administer the intervention based on recommendations by the Committee on Nutrition Services for Medicare Beneficiaries, which state that “the RD is currently the single identifiable group of health care professionals with standardized education, clinical training, continuing education, and national credentialing requirements necessary to be a directly reimbursable provider of nutrition therapy” (3). The RDs were trained by a Nutritionist, Dr. Bales, and a Health Psychologist, Dr. Vickers, to individualize and implement the intervention consistent with SCT. Once the individually tailored plan was devised, the RDs met with the participant/caregiver in the patient’s home. The RD utilized self-management education approaches to share information with the participant/caregiver about the intervention plan, providing both verbal and written instructions regarding how to improve and maximize caloric intake. She collaborated with the participant/caregiver in identifying areas for initial behavior change that matched best with the participant’s preferences, motivation, and confidence. It was critical that the participant and caregiver not feel overwhelmed with too much information or sense pressure for excessive amounts of change as that could decrease self-efficacy for change. Accordingly, the RD conducted ongoing assessment (throughout the period of the intervention) of importance and confidence related to the participant-selected priority areas for change.

After the participant/caregiver selected initial areas for behavior change, collaborative goal-setting occurred, utilizing the action plan method used in a self-management education approach (22). Goals were short-term, measurable, specific, and matched to the participant’s priorities and preferences. A maximum of three goals were selected for behavioral change. With each goal, the participant/caregiver was asked to rate his or her confidence on a scale of 1 (least) to 10 (most) in terms of ability to take the steps necessary to be successful in achieving the goal. Goals given ratings less than 7 were modified in collaboration with the participant/caregiver in order to enhance follow-through. The RD was available to answer any questions the participant/caregiver may have had. She encouraged open dialogue and provided assistance with problem solving rather than taking on the role of sole expert in all aspects of possibilities for change. The RD provided the participant with her telephone number as well as contact information for the rest of the study staff. The participant was instructed to call the RD or staff with any problems, questions, or concerns. Because the intervention was designed to be applicable in the real world setting of home health care, the RD made only one visit to the home.

Self-Management Support Calls

Because follow-up is a critical step in acting on an action plan for health behavior change, three telephone calls were used to assess progress with goals and provide ongoing self-management support. Specifically, the RD followed up 1, 2, and 4 weeks later with telephone calls to assess progress with goals, assist with problem solving around barriers, and enhance action plans based on lessons learned. Praise was provided for success in following through with behavioral changes. Goals were modified as needed to help increase participant confidence in ability to make change.

Outcomes Assessment

The Outcomes Assessment, also conducted in the home by the RA, occurred 60 days following randomization. The Outcome Assessment was conducted to evaluate immediate primary effects of the intervention, including caloric intake (based on collection of three 24-hr dietary recalls) and weight. Additionally, for those who were randomized to the intervention, an assessment of treatment fidelity was measured. This was specific for each participant based on his or her individualized treatment. This was a self-report measure and included items related to whether participants followed through with behavioral changes. A longer-term Outcome Assessment, including the same measures as that at 60 days, occurred 6 months following randomization.

Treatment Fidelity

Fidelity to treatment impacts reliability and validity of study findings (41, 42). The Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium has developed a set of best practices and guidelines for maximizing treatment fidelity in health behavior change interventions (41). We have integrated these strategies into our study by emphasizing fidelity in design (consistency with underlying theory), training of interventionists (utilizing assessments such as mock sessions and ratings of recorded sessions to determine the acquisition and maintenance of interventionists’ skills), delivery of the intervention (accuracy of treatment presentation determined through ratings of recorded sessions and regular supervision), receipt of the intervention (participant understanding of session content assessed through postsession questioning), and enactment (participant out-of-session implementation was assessed via report of intervention strategies used).

To ensure consistency of intervention content and delivery, we used standardized treatment protocols and procedures. A comprehensive Manual of Operations and Procedures was developed in the start-up period and distributed to all personnel. Written procedures existed for assessments, treatment delivery, and monitoring of treatment delivery. Study personnel were thoroughly trained in the interventions and given corrective feedback in practice sessions. Even among highly trained interventionists, there is a potential for slight deviations from treatment protocol to occur over time, commonly referred to as “intervention drift.” In order to protect against this, a “booster” training session was conducted. Additionally, we audio-taped interview and intervention sessions and 10% of these sessions were randomly selected and reviewed by Dr. Vickers for quality control purposes utilizing behavioral checklists (available upon request).

Additionally, we assessed treatment fidelity to the intervention in terms of receipt of the intervention by participants. Through participant self-report, an assessment was made of participants’ understanding of the intervention and enactment of the intervention. This was accomplished in three ways: (1) after completion of the intervention session, participants were asked by the RD if they understand what was being expected of them. If not, instructions were offered until they were understood; (2) the RD made Support Calls 1, 2, and 4 weeks following the intervention to assess treatment fidelity; and (3) at the Follow-Up Assessments, participants were asked whether and to what extent they followed through with their individualized plan.

Self-Efficacy, Goal-Setting, and Relapse Prevention

In order to assess self-efficacy, we used a 5-Item Nutrition Self-Efficacy Scale developed by Schwarzer and Renner (34). This self-efficacy item is specific to nutritional change and well-suited for the study because it allows for assessment of self-efficacy related to weight gain or maintenance. In order to assess goal-setting and relapse prevention behavior we used the Behavior Change Scale developed by Nies and colleagues (35). Self-efficacy, goal-setting, and relapse prevention behavior are potential mediator variables that we believe will be impacted with our multilevel self-management nutritional intervention (43–45). We anticipate that these variables will increase in response to intervention and that changes will be associated with increased caloric intake, our primary outcome measure. A secondary aim of our study seeks to determine whether changes in self-efficacy, goal-setting, and relapse prevention occur as a result of the intervention, and, if so, whether these changes mediate the effect of the intervention on the primary and secondary outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Little is known about the effectiveness of behavioral nutritional interventions that are theoretically based, conservative (i.e., not involving medical intervention), and targeted at older adults who are experiencing multiple comorbidities and disabilities; there are very few studies and no known randomized controlled trials concerning this research question. Consistent with the mission of the National Institute on Aging and its emphases on interventions and behavior change, the approach used in the B-NICE trial has the potential to improve health outcomes across a broad spectrum of illnesses and to reduce associated health care costs (46). Previous work has demonstrated that older adults receiving Medicare home health services who are at risk for poor nutrition compared with those who are not experience higher rates of mortality and increased health services utilization, including for those who are overweight and obese, increased rates of nursing home placement (47).

The Institute of Medicine’s expert committee on the Role of Nutrition in Maintaining Health in the Nation’s Elderly found that “there is a pressing need for research on under-nutrition in older persons,” and recommended that “The federal government, through agencies such as the NIA … support support clinical research on nutrition in older persons” (3). This expert panel specifically highlighted the importance of nutrition services delivered and evaluated in the home care setting.

The significance of the B-NICE approach lies in the evidence it will provide regarding the potential benefits of providing nutritional services in the home to a group of malnourished or at risk older adults who are receiving Medicare home health services. Such information will contribute to evidence-based behavioral health practices that can be used to guide decision makers in formulating polices related to nutrition and home health services delivery (48, 49). The B-NICE intervention is also particularly timely in reference to current health policy. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are increasingly focusing attention toward chronic care. At the time this study was implemented, a major provision of the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 that authorized the establishment of Medicare Health Support was also implemented (50). The goal of the program was to develop individualized, goal-oriented care management plans for beneficiaries with chronic illnesses, including those who were homebound. One particular area of care management includes “self-care education for the beneficiary (through approaches such as medical nutrition therapy) and education for primary caregivers and family members” delivered by an RD or nutritional professional (51). It was the intent of the law that such nutrition care plans be grounded in evidence-based guidelines; focus on health outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost savings; and be delivered by RDs. Continuing in this trajectory, following passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, CMS established the Innovation Center to identify, test, and spread new models of care and payment that result in better health care, better health, and reduced cost. Areas of focus include patient care models; seamless, coordinated models; and community and population health.

TAKE AWAY POINTS.

The Behavioral Nutrition Intervention in Community Elders (B-NICE) trial is the first evidence-based randomized controlled intervention study in the area of undernutrition and self-care education for older adults delivered in the home.

The design of the intervention was based on an extensive review of the literature, the Ecological Model, Social Cognitive Theory, and our own preliminary findings and clinical practice.

The results of the B-NICE trial will demonstrate whether nutritional services provided in the home by a Registered Dietitian are beneficial to a group of older adults who are either already malnourished or at especially high risk for undernutrition and are receiving Medicare home health services.

Future findings will contribute to evidence-based behavioral health practices that can guide decision makers in formulating polices related to nutrition and home health services delivery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (AG027560 to JLL).

Contributor Information

JULIE L. LOCHER, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Center for Aging, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Department of Health Care Organization and Policy, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Lister Hill Center for Health Policy, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Nutrition Obesity Research Center, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

CONNIE W. BALES, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA; Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Center, Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

AMY C. ELLIS, Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

JEANNINE C. LAWRENCE, Department of Human Nutrition and Hospitality Management, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, USA.

LAURA NEWTON, Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

CHRISTINE S. RITCHIE, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Center for Aging, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Lister Hill Center for Health Policy, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Nutrition Obesity Research Center, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Department of Veterans Affairs, Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

DAVID L. ROTH, Center for Aging, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Department of Veterans Affairs, Birmingham/Atlanta Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Department of Biostatistics, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

DAVID L. BUYS, Division of Gerontology, Geriatrics, and Palliative Care, University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), Birmingham, Alabama, USA; Center for Aging, UAB, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

KRISTIN S. VICKERS, Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA.

References

- 1.Thomas D, editor. Clinics in geriatric medicine: under-nutrition in the elderly. 2002;18(I) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas D, editor. II. 2001. The journal of gerontology: biological sciences and medical sciences: nutrition, physical activity, and quality of life in older adults; p. 56A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Nutrition Services for Medicare Beneficiaries. The Role of Nutrition in Maintaining Health in the Nation’s Elderly: Evaluating evaluating Coverage of Nutrition Services for the Medicare Population. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milne AC, Avenell A, Potter J. Meta-analysis: protein and energy supplementation in older people. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:37–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simmons SF, Alessi C, Schnelle JF. An intervention to increase fluid intake in nursing home residents: prompting and preference compliance. J Amer Ger Soc. 2001;49:926–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathey MF, Siebelink E, de Graaf C, Van Staveren WA. Flavor enhancement of food improves dietary intake and nutritional status of elderly nursing home residents. J Geron: Med Sci. 2001;56A:M200–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.4.m200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathey MF, Vanneste VGG, de Graaf C, de Groot L, van Staveren WA. Health effect of improved meal ambience in a Dutch nursing home: a 1-year intervention study. Preven Med. 2001;32:416–23. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein MA, Tucker KL, Ryan ND, O’Neill EF, Clements KM, Nelson ME, et al. Higher dietary variety is associated with better nutritional status in frail elderly people. J Amer Diet Soc. 2002;102:1096–104. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90246-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musson ND, Kincaid J, Ryan P, Glussman B, Varone L, Gamarra N, et al. Nature, nurture, nutrition: interdisciplinary programs to address the prevention of malnutrition and dehydration. Dysphagia. 1990;5:96–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02412651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Ort S, Phillips LR. Nursing interventions to promote functional feeding. J Geron Nurs. 1995;10:6–14. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19951001-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simmons SF, Bertrand R, Shier V, Sweetland R, Moore TJ, Hurd DT, Schnelle JF. A preliminary evaluation of the paid feeding assistant regulation: impact on feeding assistance care process quality in nursing homes. Geron. 2007;47(2):184–92. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sahyoun NR, Pratt CA, Anderson A. Evaluating nutrition interventions for older adults: a proposed framework. J Amer Diet Ass. 2004;104:58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharkey JR. The influence of nutritional health on physical function: a critical relationship for homebound older adults. Generations. 2004 Fall;:34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grzywacz JG, Fuqua J. The social ecology of health: leverage points and linkages. Behav Med. 2000;26(3):101–16. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McElroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Edu Quart. 1988;15:351–77. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hovell MF, Wahlgren DR, Gehrman C. The behavioral ecological model: integrating public health and behavioral science. In: Di Clemente RJ, Crosby R, Kegler M, editors. New and Emerging Theories in Health Promotion Practice & Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. pp. 347–85. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rimer B, Glanz K. Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice. 2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005. Accessed at http://cancer.gov/aboutnci/oc/theory-at-a-glance/print. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locher JL, Roth DL, Ritchie CS, Cox K, Sawyer P, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Body mass index, weight loss, and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(12):1389–92. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie CS, Locher JL, Roth DL, McVie T, Sawyer P, Allman R. Unintentional weight loss predicts decline in ADL function and life space mobility over four years among community dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(1):67–75. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Locher JL, Sharkey JS. An ecological model for understanding eating behavior in older adults. In: Bales CW, Ritchie CS, editors. Handbook of Clinical Nutrition and Aging. 2. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psych Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Beh Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psych Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed at on 11 October 2007.];OASIS Home Page. http://www.cms.hhs.gov/oasis/

- 29.Ross CE, Reynolds JR. The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents’ psychological well-being. Amer Sociological Rev. 1996;65:581–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Food Security in the United States: The Current Population Survey Food Security Supplement (CPS-FSS) United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services; [Accessed at on 11 October 2007.]. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data/foodsecurity/cps/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atchison KA, Dolan TA. Development of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Dental Edu. 1990;54:680–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leake JL. An index of chewing ability. J Public Health Dentistry. 1990;50:262–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1990.tb02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker PS, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. JAGS. 2003;51(11):1610–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarzer R, Renner B. [on 13 September 2005.];Health-specific self-efficacy scales. Accessed at http://userpage.fuberlin.de/~health/healself.pdf.

- 35.Nies MA, Hepworth JT, Wallston KA, Kershaw TC. Evaluation of an instrument for assessing behavioral change in sedentary women. J Nurs Scholar. 2001;33(4):349–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2001.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Locher JL, Ritchie CS, Robinson CO, Roth DL, West DS, Burgio KL. A multidimensional approach to understanding under-eating in homebound older adults: the importance of social factors. Gerontologist. 2008 Apr;48(2):223–34. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.2.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panel on Macronutrients, Panel on the Definition of Dietary Fiber, Subcommittee on Upper Reference Levels of Nutrients, Subcommittee on Interpretation and Uses of Dietary Reference Intakes, and Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intake for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [on 20 July 2006.]. Accessed at www.nap.edu/catolog/10490.html. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thompson FE, Subar AF. Dietary assessment methodology. In: Coulston AM, Boushey CJ, editors. Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. 2. Philadelphia: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Y, Roth DL, Ritchie CS, Burgio KL, Locher JL. Reliability and predictive validity of caloric intake measures from the 24-hour dietary recalls of homebound older adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 May;110(5):773–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennis B, Ernst N, Hjortland M, Tillotson J, Grambsch V. The NHLBI Nutrition Data System. J Am Diet Assoc. 1980;6:641–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psych. 2004;23(5):443–51. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psych. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichstein KL, Riedel BW, Grieve R. Fair tests of clinical trials: a treatment implementation model. Advances in Behavior Research and Therapy. 1994;16:1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psych Meth. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psych Meth. 2002;4:422–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. [on 10 October 2007.];National Institute on Aging Web site. Accessed at http://www.nia.nih.gov/

- 47.Yang Y, Brown CJ, Burgio KL, Kilgore ML, Ritchie CS, Roth DL, et al. Undernutrition at baseline and health services utilization and mortality over a 1-yr period in older adults receiving Medicare home health services. J Am Med Directors Assoc. 2011 May;12(4):287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levkoff SE, Chen H, Fisher JE, McIntyre JS. Evidence-Based Behavioral Health Practices for Older Adults: A Guide to Implementation. New York: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49. [on 11 October 2007];Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Data Compendium. (2006). Accessed at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DataCompendium/18_2006_Data_Compendium.asp#TopOfPage.

- 50.Medicare Health Support. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [on 11 October 2007.]. Accessed at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/CCIP/ [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith R. Medicare reform: what it means to the future of dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(5):734–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]