Abstract

The secretion of the hormone insulin from beta cells is modulated by the expression of the dense core vesicle transmembrane protein IA-2. Since IA-2 is found in neuroendocrine cells throughout the body, the present experiments were initiated to determine whether the expression of IA-2 also modulates the secretion of neurotransmitters. Using the dopamine-secreting pheochromocytoma cell line PC12, we found that the overexpressions of IA-2 increased the cellular content and secretion of dopamine, whereas the knockdown of IA-2 by siRNA decreased the cellular content and secretion of dopamine. Neither the overexpression nor knockdown of IA-2 influenced the uptake of [H3]dopamine by PC12 cells, but did influence the amount of [H3]dopamine secreted. Overexpression of IA-2 also increased the level of the dense core vesicle-associated proteins Rab3A, IA-2β and secretogranin II, whereas the knockdown of IA-2 decreased the level of these proteins. We conclude that the expression of IA-2 profoundly influences the function of dense core vesicles and has a broad modulating effect on the cellular content and secretion of both hormones and neurotransmitters.

Keywords: IA-2, siRNA, PC12, Dopamine, Hormones, Neurotransmitters

1. Introduction

IA-2 and IA-2β are major autoantigens in type 1 diabetes (Lan et al., 1994, 1996; Lu et al., 1996). About 70% of newly diagnosed patients have autoantibodies to IA-2 and about 50% have autoantibodies to IA-2β. These autoantibodies appear years before the onset of clinical disease and in combination with autoantibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase and/or insulin have become predictive markers for this disease (Notkins and Lernmark, 2001). Population screening studies have shown that subjects with autoantibodies to two or more of these major autoantigens are at a 50% or greater risk of developing type 1 diabetes within 5 year and this information is being used to enter subjects into therapeutic intervention trials (Notkins, 2007).

Based on sequence, IA-2 and IA-2β, also known as ICA512 and phogrin, respectively, are members of the transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) family, but are enzymatically inactive with standard PTP substrates because of two critical amino acid substitutions in the PTP domain (Magistrelli et al., 1996). Both proteins consist of an intracellular, transmembrane and luminal domain. IA-2 is 979 and IA-2β is 986 amino acids in length. Their intracellular domains are 74% identical, whereas their luminal domains are only 26% identical. IA-2 and IA-2β are located on human chromosomes 2q35 and 7q36, respectively, encoded by 23 exons (Saeki et al., 2000; Kubosaki et al., 2004) and expressed in neuroendocrine cells (e.g., pancreatic islets, brain) throughout the body (Solimena et al., 1996; Wasmeier and Hutton, 1996; Roberts et al., 2001; Kawakami et al., 2007; Takeyama et al., 2009). Electron microscopic studies revealed that both proteins are transmembrane proteins in dense core vesicles (DCVs).

The mouse and rat homologs of IA-2 and IA-2β are similar in almost all respects to their human counterparts. At the protein level their intracellular domains are 98–99% identical to human IA-2 and IA-2β. Recently, we succeeded in knocking out the individual IA-2 and IA-2β genes and generated double knockout (DKO) mice (Kubosaki et al., 2004, 2005; Saeki et al., 2002). These KO mice did not develop diabetes, but showed abnormal glucose tolerance tests, impaired insulin secretion and a reduction in the insulin content of beta cells. In vitro studies using the insulin-secreting mouse beta cell line, MIN-6, showed that the knockdown of IA-2 by siRNA also impaired insulin secretion, whereas the overexpression of IA-2 enhanced insulin secretion (Harashima et al., 2005). Since IA-2 also is expressed in DCV in the brain and adrenals, the present study was initiated to determine whether IA-2 modulates the secretion of not only hormones, but also the secretion of neurotransmitters. To test this hypothesis, the dopamine-secreting rat pheochromocytoma cell line, PC12, was used in IA-2 knockdown and overexpression experiments.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Cell culture reagents were purchased from BioSource International (Camarillo, CA) and GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). A dopamine ELISA kit was obtained from Rocky Mountain Diagnostic Inc (Colorado Springs, CO). Both mouse anti-IA-2 and IA-2β monoclonal antibodies (mAb) were gifted from Dr. Keiichi Saeki (University of Tokyo, Japan). IA-2 mAb, CC20, was raised against mouse recombinant IA-2 (aa 696-979) and recognized an epitope between aa 696-747 (Takeyama et al., 2009). IA-2β mAb, WT4 (Kawakami et al., 2007), was raised against recombinant mouse IA-2β (aa 415-1001) and recognized an epitope between aa 506-534. Mouse anti-α-tubulin mAb was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Rabbit anti-Rab3A pAb and rabbit anti-secretogranin II (SgII) pAb were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylse (TH) pAb and rabbit anti-DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) pAb were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Rabbit anti-Rabphiline 3A was purchased from Affinity BioReagents (Golden, CO) and [H3]dopamine from Amersham Pharmacia (Piscataway, NJ).

2.2. Establishment of stable cell lines

PC12 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum and 10% horse serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in 95% air and 5% CO2. Full length IA-2 inserted into pCMV-Tag3 (Harashima et al., 2005) was transfected into PC12 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). After 6 weeks in culture, several stably transfected cell lines were established by G418 selection and limiting dilutions. Three of these with high expression of IA-2, were further analyzed and showed similarity in dopamine content and secretion. One of these lines (PC12/IA-2) was used in all subsequent studies. pCMV-Tag3 (mock vector) was used to transfect PC12 cells under the same conditions as described. Several stably transfected cell lines were established, and one of these, PC12/mock, was used in all subsequent studies.

2.3. siRNA and transfection

IA-2 siRNA and nonsilencing (control) siRNA were prepared by Qiagen (Valencia, CA) as reported previously (Harashima et al., 2005). Target sequences were derived from the cDNA sequences of human and rat IA-2: 5′-AAGTCTGTATTCAGGATGGCTT-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 152-173 of human IA-2 mRNA and nucleotides 170-191 of rat mRNA. Control siRNA target (random sequence) was 5′-AATTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTT-3′. A total of 1 × 105 nontransfected PC12 cells or IA-2-transfected PC12 cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates coated with poly-L-lysine (Sigma) and cultured for 24 h. The cells then were transfected with 2 μg of IA-2 siRNA or 2 μg of control siRNA by Lipofectamine 2000. Forty-eight hours later cells and culture fluid were collected.

2.4. Western blotting

Samples were sonicated in ice-cold lysis buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and protease inhibitor mixture. Lysates were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 10 min to remove insoluble debris. Protein concentrations in the supernatants were determined using Bradford protein assay (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA). The proteins in the extract (50 μg) were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE.

2.5. Dopamine content

Cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured for 2 days. The dopamine content was determined with a dopamine ELISA kit.

2.6. Dopamine secretion test

PC12/mock and PC12/IA-2 cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates coated with poly-L-lysine at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured in DMEM for 2 days. PC12 cells transfected with siRNAs also were incubated for 48 h after transfection. The dopamine secretion test was conducted as previously described with slight modification (Shoji-Kasai et al., 2002). The cells were washed twice with a low (basal) K+ buffer (20 mM Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, and 11 mM glucose containing 4.7 mM KCl). After washing the cells were stimulated for 3 min with low K+ buffer (4.7 mM KCl) or with high K+ buffer (25 mM KCl) with or without 160 nM phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA) (Sigma) for 6 min at 37 °C. The media were collected and rapidly centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 s at 4 °C. The supernatants then were measured for the amount of dopamine secreted.

2.7. Measurement of uptake and release of [H3]dopamine

The experiment was performed as previously described (Ireland et al., 1995). PC12/mock and PC12/IA-2 cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates coated with poly-L-lysine at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured for 2 days. PC12 cells (1 × 105) transfected with siRNAs also were incubated for 48 h after transfection. Cells were washed three times with oxygenated Krebs–Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) buffer containing 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KC1, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, and 24.2 mM NaHCO3 and was equilibrated with 5% CO2/95% O2. For the uptake assays, [H3]dopamine (0.5 μCi) was added and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. After removal of excess radiolabeled ligands, the cells were washed rapidly three times with an ice-cold KRH buffer. The radioactivity remaining in the cells was extracted with NaOH and measured with liquid scintillation counter. For the release assays, cells were incubated with [H3]dopamine for 2 h and washed three times. The cells then were stimulated with low K+ buffer (4.7 mM KCl) or with high K+ buffer (25 mM KCl) or high K+ buffer plus 160 nM PMA for 6 min at 37 °C. The media were collected and rapidly centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 s at 4 °C. The radioactivity in the supernatants then was measured with a liquid scintillation counter.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed three times and assays were done in triplicate. Unless indicated otherwise, data are expressed as the mean ± standard error (SEM) of the three experiments. The Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

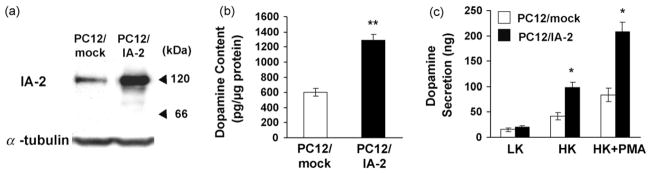

PC12 cells were transfected with full length human IA-2 (aa 1-979) and stable cell lines were established by G418 selection and limiting dilutions. Fig. 1a shows that the IA-2-transfected PC12 cells (PC12/IA-2) express considerably more IA-2 protein than the mock-transfected cells (PC12/mock) as determined, respectively, by Western blot (Fig. 1a) and confocal microscopy (data not shown). The predominant 120 kDa band in Fig. 1a represents the full length of IA-2. In beta cells IA-2 is cleaved immediately after the first KK site (aa 386) resulting in a prominent 66 kDa protein band (Xie et al., 1998) which is barely detectable in the PC12 cells, perhaps due to differences in the protein convertases of PC12 cells as compared to beta cells.

Fig. 1.

IA-2 overexpression in PC12 cells. (a) Western blot showing overexpression of IA-2. (b) Dopamine content as determined by ELISA in mock-transfected PC12 cells (PC12/mock) and IA-2-transfected PC12 cells (PC12/IA-2). (c) Effect of low (LK) and high (HK) concentrations of K+ plus PMA on dopamine secretion in PC12/mock cells and PC12/IA-2 cells. The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

To determine whether the overexpression of IA-2 influences dopamine secretion, the amount of dopamine in the PC12 cells was first determined. As seen in Fig. 1b, 2.0–2.5 times more dopamine was found in the PC12/IA-2 cells than in the PC12/mock cells (P < 0.01). Stimulation of PC12/IA-2 cells with a low concentration of K+ revealed no difference in the secretion of dopamine as compared with the PC12/mock cells. However, with a high concentration of K+, two to three times more dopamine was secreted from the PC12/IA-2 cells than from PC12/mock cells (P < 0.05). When a high concentration of K+ plus PMA was used for stimulation nearly 3 times as much dopamine was secreted from the PC12/IA-2 cells as compared to the PC12/mock cells (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1c). Although over-expression of IA-2 resulted in a significant increase in the amount of dopamine secreted, fractional secretion (i.e., amount of dopamine secreted divided by the total dopamine content of the cells) was not significantly different when PC12/mock cells were compared with PC12/IA-2 cells following stimulation with low K+, high K+ or high K+ plus PMA (Fig. 2a: data from Fig. 1b and c).

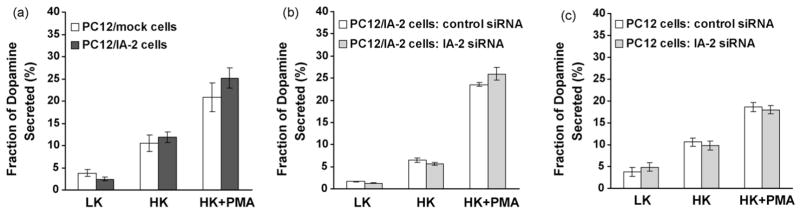

Fig. 2.

Fraction of dopamine secreted from cells stimulated with low K+, high K+ or high K+ plus PMA. (a) Mock or IA-2-transfected PC12 cells; (b) IA-2-transfected PC12 cells treated with control siRNA or IA-2 siRNA; (c) PC12 cells treated with control siRNA or IA-2 siRNA.

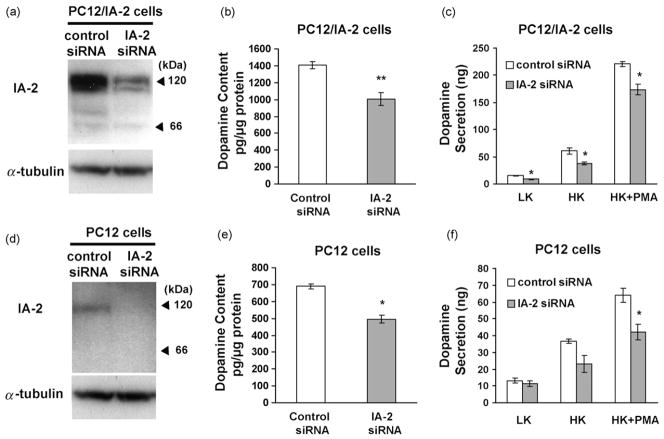

To determine the effect of knocking down IA-2 on dopamine secretion, PC12/IA-2 cells were treated with IA-2 siRNA or control siRNA. IA-2 siRNA resulted in approximately an 80% decrease in IA-2 protein expression by Western blot (Fig. 3a) and about a 29% decrease in the dopamine content of the cells as compared to the cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 3b). PC12/IA-2 cells treated with IA-2 siRNA followed by stimulation with low K+, high K+, or high K+ plus PMA decreased dopamine secretion by 45%, 38% and 22%, respectively, as compared to cells treated with control siRNA (Fig. 3c). Similar results were obtained with PC12 cells not transfected with IA-2 (Fig. 3d–f). In these cells (Fig. 3d), IA-2 expression is considerably lower than in PC12/IA-2 cells as determined by Western blot, but IA-2 siRNA treatment results in a substantial further reduction in IA-2 expression. In turn, this resulted in approximately a 28% decrease in the dopamine content of the PC12 cells (Fig. 3e) and a 35% decrease in the secretion of dopamine from PC12 cells stimulated with high K+ plus PMA (Fig. 3f). Although the knockdown of IA-2 by siRNA resulted in a significant decrease in the amount of dopamine secreted, fractional secretion was not significantly different when PC12/IA-2 cells (Fig. 2b: data from Fig. 3b and c) or PC12 cells (Fig. 2c: data from Fig. 3e and f) were treated with control siRNA or IA-2 siRNA and then stimulated with low K+, high K+ or high K+ plus PMA.

Fig. 3.

Treatment of PC12/IA-2 cells and PC12 cells with IA-2 siRNA. Treatment of IA-2 overexpressing PC12 cells (PC12/IA-2) with IA-2 siRNA showing: (a) IA-2 expression by Western blot; (b) dopamine content; and (c) LK, HK and HK plus PMA-induced dopamine secretion. Treatment of PC12 cells with IA-2 siRNA showing: (d) IA-2 expression by Western blot; (e) dopamine content; and (f) LK, HK and HK plus PMA-induced dopamine secretion. The values are the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

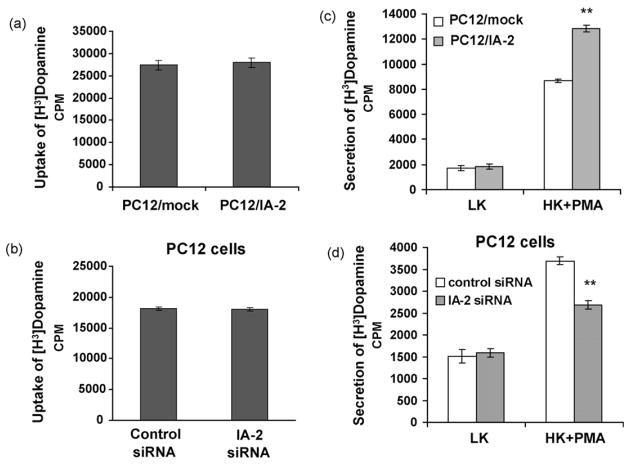

To see if either overexpression or knockdown of IA-2 affected the uptake of dopamine, [H3]dopamine was added to the cells and the amount taken up was determined. Neither the overexpression of IA-2 in PC12/IA-2 versus PC12/mock cells (Fig. 4a) nor the knockdown of IA-2 in PC12 cells (IA-2 siRNA versus control siRNA) (Fig. 4b) affected the uptake of [H3]dopamine. However, PC12 cells overexpressing IA-2 and stimulated with high K+ plus PMA secreted about 48% more [H3]dopamine than the mock-transfected cells (Fig. 4c). Conversely, PC12 treated with IA-2 siRNA and stimulated with high K+ plus PMA, secreted approximately 28% less [H3]dopamine than the cells that had been treated with control siRNA (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

[H3]dopamine uptake and secretion by K+ stimulation. (a) [H3]dopamine uptake and (c) [H3]dopamine secretion by HK plus PMA as determined by measuring the radioactivity in the supernatant of mock-transfected PC12 cells (PC12/mock) as compared to IA-2-transfected PC12 cells (PC12/IA-2). (b) [H3]dopamine uptake and (d) [H3]dopamine secretion by HK plus PMA as determined by measuring the radioactivity in the supernatant of PC12 cells treated with IA-2 siRNA or control siRNA. The values are the mean ± SEM of triplicate wells in a single experiment, but are representative of three independent experiments (**, P < 0.01).

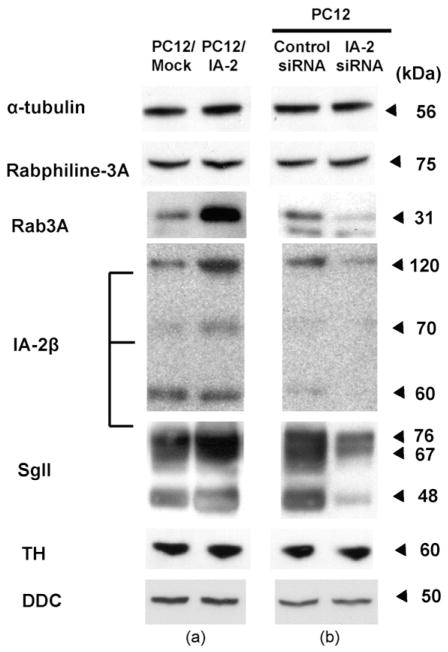

Recent studies on beta cells showed that overexpression of IA-2 increased the number of DCV (Harashima et al., 2005), whereas the knockout of IA-2 decreased the number of DCV (Cai et al., unpublished data). This increase and decrease in IA-2 and the number of DCV is associated, respectively, with an increase and decrease in other DCV proteins. To see if this also was the case with PC12 cells, three proteins known to be integral components of DCV were evaluated by Western blots. As seen in Fig. 5a, Rab3A, IA-2β and SgII were all increased in PC12 cells overexpressing IA-2, whereas all three of these proteins were decreased in PC12 cells in which IA-2 was knocked down (Fig. 5b). Rabphiline-3A, which binds to Rab3A, but is not an integral component of DCV, was not affected nor was the cytoplasmic protein α-tubulin. Tyrosine hydroxylase and DOPA decarboxylase, the enzymes required for catecholamine synthesis, also were not increased or decreased.

Fig. 5.

Expression of DCV-associate proteins as determined by Western blot. (a) Transfection of PC12 cells with IA-2 (PC12/IA-2) increases the expression of the DCV-associated proteins Rab3, IA-2β, and secretogranin II (SgII). (b) Treatment of nontransfected PC12 cells with IA-2 siRNA decreased the expression of the DCV-associated proteins Rab3, IA-2β and SgII. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and DOPA decarboxylase (DDC) showed no change.

4. Discussion

Previous studies on IA-2 focused primarily on its role in beta cells. Since IA-2 is a transmembrane DCV protein and present in most neuroendocrine secretory cells, we postulated that IA-2 also would influence the secretion of neurotransmitters. In the present study we showed that the knockdown of IA-2 or its overexpression in PC12 cells suppressed or enhanced, respectively, the secretion of the neurotransmitter dopamine. Of particular interest, the knockdown of IA-2 in PC12 cells decreased the total amount of dopamine secreted, but did not affect fractional secretion. Conversely, the overexpression of IA-2 in PC12 cells increased the total amount of dopamine secreted, but also did not affect fractional secretion. Similarly, Henquin et al. found little change in the fractional rate of insulin secretion when beta cells from IA-2/IA-2β double knockout mice were compared with wild type mice, although the total amount of insulin secreted and the insulin content of the beta cells was decreased (Henquin et al., 2008).

Precisely how IA-2 modulates dopamine secretion in PC12 cells has not been determined, but we suspect that the process is not dissimilar to that observed with IA-2 in mouse beta cells and in C. elegans. Previously, we showed by EM that overexpression of IA-2 in both MIN-6 cells and in C. elegans increased the number of DCV and that the knockout of IA-2 in mice and in C. elegans decreased the number of DCV (Harashima et al., 2005; Cai et al., 2009) (Cai, et al., unpublished data). Moreover, we showed that the half-life of DCV in MIN-6 cells in which IA-2 is overexpressed (40.2 h) is longer than that of DCV vesicles in MIN-6 cells in which IA-2 is not overexpressed (22.5 h) (Harashima et al., 2005). This increase in half-life results in an increase in the number of DCV and, in turn, this increases the insulin content of the beta cells and the amount of insulin secreted upon stimulation with glucose. Recently we also found that the half-life of DCV in beta cells from IA-2 knockout mice is considerably shorter than that of DCV in beta cells from wild type mice (Cai et al., unpublished data). This decrease in half-life results in a decrease in the number of DCV which, in turn, results in a decrease in the insulin content of beta cells and the amount of insulin secreted upon stimulation with glucose. In the present study, although not directly proven, support for the idea that IA-2 affects the number of DCV in PC12 cells comes from the demonstration that the DCV-associated proteins IA-2β, Rab3A and SgII are increased and decreased, respectively, in parallel with the overexpression and knockdown of IA-2 as previously demonstrated in MIN-6 cells (Harashima et al., 2005). The observation that there is no difference in the uptake of [H3]dopamine in the cells in which IA-2 has been overexpressed or knocked down argues that the respective increase or decrease in the dopamine content of these cells is not due to IA-2 induced alterations in the uptake of dopamine by transporters on the cell membrane. The fact that fractional secretion also is not impaired suggests that the effect of IA-2 on the stabilization of DCV may be more important than any effect IA-2 may have on the trafficking of DCV or the rate of cargo release. The possibility that IA-2 may contribute to cargo loading is suggested by fractionation studies which showed statistically more [H3]dopamine in the enriched DCV fractions of PC12/IA-2 cells as compared to PC12/mock cells (Supplemental Material, Fig. 1a,b).

Although IA-2 and IA-2β are important transmembrane DCV structural proteins and their degree of expression affects secretion, they also may have other functions. For example, IA-2 has been reported to bind to more than a dozen different proteins and these interactions (Hu et al., 2005) have been shown or postulated to result in a variety of activities (e.g., heterodimerization, trafficking from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, mRNA stabilization, biogenesis, DCV stabilization) but confirmatory studies are needed (Harashima et al., 2005; Knoch et al., 2004; Mziaut et al., 2008; Gross et al., 2002; Trajkovski et al., 2008).

The demonstration here that IA-2 can modulate dopamine secretion complements and provides further insight into the recent report that the knockout in mice of IA-2 and IA-2β results in profound changes in behavior and learning (Nishimura et al., 2009). Taken together these findings raise the possibility that at the human level subtle changes in the secretion of neurotransmitters, secondary to alterations in the expression of DCV structural proteins, may be involved in affective disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health and in part by a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Fellowship (T.N.). The authors thank Dr. Keiichi Saeki and Dr. Takashi Onodera for providing antibodies.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.023.

References

- Cai T, Hirai H, Fukushige T, Yu P, Zhang G, Notkins AL, Krause M. Loss of the transcriptional repressor PAG-3/Gfi-1 results in enhanced neurosecretion that is dependent on the dense-core vesicle membrane protein IDA-1/IA-2. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross S, Blanchetot C, Schepens J, Albet S, Lammers R, den Hertog J, Hendriks W. Multimerization of the protein-tyrosine phosphatase (PTP)-like insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus autoantigens IA-2 and IA-2beta with receptor PTPs (RPTPs). Inhibition of RPTPalpha enzymatic activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48139–48145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima S, Clark A, Christie MR, Notkins AL. The dense core transmembrane vesicle protein IA-2 is a regulator of vesicle number and insulin secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8704–8709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408887102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henquin JC, Nenquin M, Szollosi A, Kubosaki A, Louis Notkins A. Insulin secretion in islets from mice with a double knockout for the dense core vesicle proteins islet antigen-2 (IA-2) and IA-2beta. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:573–581. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YF, Zhang HL, Cai T, Harashima S, Notkins AL. The IA-2 interactome. Diabetologia. 2005;48:2576–2581. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland LM, Yan CH, Nelson LM, Atchison WD. Differential effects of 2,4-dithiobiuret on the synthesis and release of acetylcholine and dopamine from rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1453–1462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami T, Saeki K, Takeyama N, Wu G, Sakudo A, Matsumoto Y, Hayashi T, Onodera T. Detection of proteolytic cleavages of diabetes-associated protein IA-2 beta in the pancreas and the brain using novel anti-IA-2 beta monoclonal antibodies. Int J Mol Med. 2007;20:177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoch KP, Bergert H, Borgonovo B, Saeger HD, Altkruger A, Verkade P, Solimena M. Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein promotes insulin secretory granule biogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:207–214. doi: 10.1038/ncb1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubosaki A, Gross S, Miura J, Saeki K, Zhu M, Nakamura S, Hendriks W, Notkins AL. Targeted disruption of the IA-2beta gene causes glucose intolerance and impairs insulin secretion but does not prevent the development of diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2004;53:1684–1691. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubosaki A, Nakamura S, Notkins AL. Dense core vesicle proteins IA-2 and IA-2beta: metabolic alterations in double knockout mice. Diabetes. 2005;54 (Suppl 2):S46–51. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.s46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan MS, Lu J, Goto Y, Notkins AL. Molecular cloning and identification of a receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase, IA-2, from human insulinoma. DNA Cell Biol. 1994;13:505–514. doi: 10.1089/dna.1994.13.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan MS, Wasserfall C, Maclaren NK, Notkins AL. IA-2, a transmembrane protein of the protein tyrosine phosphatase family, is a major autoantigen in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6367–6370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Li Q, Xie H, Chen ZJ, Borovitskaya AE, Maclaren NK, Notkins AL, Lan MS. Identification of a second transmembrane protein tyrosine phosphatase, IA-2beta, as an autoantigen in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: precursor of the 37-kDa tryptic fragment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2307–2311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistrelli G, Toma S, Isacchi A. Substitution of two variant residues in the protein tyrosine phosphatase-like PTP35/IA-2 sequence reconstitutes catalytic activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;227:581–588. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mziaut H, Kersting S, Knoch KP, Fan WH, Trajkovski M, Erdmann K, Bergert H, Ehehalt F, Saeger HD, Solimena M. ICA512 signaling enhances pancreatic beta-cell proliferation by regulating cyclins D through STATs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:674–679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710931105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Kubosaki A, Ito Y, Notkins AL. Disturbances in the secretion of neurotransmitters in IA-2/IA-2β null mice: changes in behavior, learning and lifespan. Neuroscience. 2009;159:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notkins AL. New predictors of disease. Molecules called predictive autoantibodies appear in the blood years before people show symptoms of various disorders Tests that detected these molecules could warn of the need to take preventive action. Sci Am. 2007;296:72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notkins AL, Lernmark A. Autoimmune type 1 diabetes: resolved and unresolved issues. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1247–1252. doi: 10.1172/JCI14257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts C, Roberts GA, Lobner K, Bearzatto M, Clark A, Bonifacio E, Christie MR. Expression of the protein tyrosine phosphatase-like protein IA-2 during pancreatic islet development. J Histochem Cytochem. 2001;49:767–776. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki K, Xie J, Notkins AL. Genomic structure of mouse IA-2: comparison with its human homologue. Diabetologia. 2000;43:1429–1434. doi: 10.1007/s001250051550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki K, Zhu M, Kubosaki A, Xie J, Lan MS, Notkins AL. Targeted disruption of the protein tyrosine phosphatase-like molecule IA-2 results in alterations in glucose tolerance tests and insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2002;51:1842–1850. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji-Kasai Y, Itakura M, Kataoka M, Yamamori S, Takahashi M. Protein kinase C-mediated translocation of secretory vesicles to plasma membrane and enhancement of neurotransmitter release from PC12 cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1390–1394. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solimena M, Dirkx R, Jr, Hermel JM, Pleasic-Williams S, Shapiro JA, Caron L, Rabin DU. ICA 512, an autoantigen of type I diabetes, is an intrinsic membrane protein of neurosecretory granules. EMBO J. 1996;15:2102–2114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama N, Ano Y, Wu G, Kubota N, Saeki K, Sakudo A, Momotani E, Sugiura K, Yukawa M, Onodera T. Localization of insulinoma associated protein 2, IA-2 in mouse neuroendocrine tissues using two novel monoclonal antibodies. Life Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trajkovski M, Mziaut H, Schubert S, Kalaidzidis Y, Altkruger A, Solimena M. Regulation of insulin granule turnover in pancreatic {beta}-cells by cleaved ICA512. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33719–33729. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804928200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasmeier C, Hutton JC. Molecular cloning of phogrin, a protein-tyrosine phosphatase homologue localized to insulin secretory granule membranes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18161–18170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.18161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Deng YJ, Notkins AL, Lan MS. Expression, characterization, processing and immunogenicity of an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus autoantigen, IA-2, in Sf-9 cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;113:367–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.