Abstract

HIV-infected persons who use drugs (PWUDs) are particularly vulnerable for suboptimal combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) adherence. A systematic review of interventions to improve cART adherence and virologic outcomes among HIV-infected PWUDs was conducted. Among the 45 eligible studies, randomized controlled trials suggested directly administered antiretroviral therapy, medication-assisted therapy (MAT), contingency management, and multi-component, nurse-delivered interventions provided significant improved short-term adherence and virologic outcomes, but these effects were not sustained after intervention cessation. Cohort and prospective studies suggested short-term increased cART adherence with MAT. More conclusive data regarding the efficacy on cART adherence and HIV treatment outcomes using cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, peer-driven interventions and the integration of MAT into HIV clinical care are warranted. Of great concern was the virtual lack of interventions with sustained post-intervention adherence and virologic benefits. Future research directions, including the development of interventions that promote long-term improvements in adherence and virologic outcomes, are discussed.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, intervention, adherence, persons who use drugs (PWUDs), HIV and drug use, combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), viral load, HIV treatment outcomes, antiretroviral adherence interventions, behavioral aspects of HIV management

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of potent, combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) beginning in the mid-1990s transformed HIV/AIDS into a chronic condition by suppressing viral replication and restoring damaged immune systems [1–3]. Similar to the treatment of other chronic conditions, improved health outcomes among individuals with HIV are contingent on relatively stringent and high levels of adherence to cART [4]. Among the estimated 1.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), only one in five has achieved virological suppression [5]. Though cART combinations differ in terms of their toxicities, potency and pharmacokinetic half-lives, resulting in differing levels of adherence to achieve viral suppression [6–8], the success of cART, nevertheless, ultimately depends entirely on adequate adherence. Ultimately, high levels of adherence are required to robustly suppress plasma HIV RNA levels (viral load; VL) [9], and incomplete adherence has been associated with virological failure and the potential development of antiretroviral resistance [10–13, 8, 14, 15].

A particularly vulnerable population, both with respect to high HIV rates and problematic cART adherence, are people who use drugs (PWUDs). Recent surveillance data within the US suggest that approximately 9% of HIV diagnoses among adults and adolescents in 2010 were attributable to injection drug use [16]. In a seminal epidemiological review of HIV rates among IDUs, Mathers [17] reported HIV prevalence rates among people who inject drugs (PWIDs) as 20–40% in five countries and over 40% in nine, with approximately 3 million HIV-infected PWIDs worldwide. Stimulant use, such as methamphetamine, is also associated with high HIV seroconversion rates among men who have sex with men. These rates are between two and four times that of MSM who do not use this drug, presumably from engaging in concurrent drug and sexual HIV-risk behaviors [18–19].

HIV-infected PWUDs have reduced access to cART, initiate therapy at advanced stages of HIV infection, and are more likely to experience problematic adherence compared to those who do not use drugs [20]. As a result, clinicians may not prescribe cART to PWUDs, particularly because of cited evidence conferring the emergence of viral resistance and the transmission of drug-resistant HIV strains among non-adherent patients [13, 21–22]. The data among HIV-infected PWUDs, however, have not provided empiric evidence that PWUDs ultimately develop increased levels of drug-resistant strains and transmit resistant virus. HIV-infected drug users can achieve the same levels of adherence as people living with HIV/AIDS who have never used drugs [23]. Survival among HIV-infected patients initiating cART with and without a history of injection drug use did not differ [24], suggesting cART access is the problem. Despite this, many HIV treatment trials have excluded drug users to date for a variety of reasons that often complicate cART delivery and maintenance, including the instability resulting from recurrent drug-seeking behaviors, frequent homelessness and comorbid psychiatric illness [20, 25–26].

The catalysts behind conducting this systematic review stemmed from participation in two pivotal investigations: the guidelines committee of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care (IAPAC) that created the first recommendations for linkage to care and cART adherence [27], and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) release of the Prevention Research Synthesis HIV Medication Adherence Review [28]. Given the international emphasis on the Seek, Test, Treat and Retain paradigm, a core component of which is adherence to cART regimens, both investigations represent a timely and crucially-needed review of the antiretroviral adherence field. Importantly, the CDC review identifies methodological limitations extant in the current research base. Some of the efficacy criteria used to evaluate the interventions were somewhat stringent, however, including an analytic sample of at least 40 participants per study arm, at least a 60% retention rate (or medical chart recovery) for each study arm, and no evidence for negative intervention effects (in a primary or replication study) for any HIV-related behavioral or biologic outcome. Such criteria would likely not allow for the identification of promising pilot trials, which are inherently smaller in scope, or more broadly for the detection of patterns in the efficacy, or lack thereof, of different classes of interventions. Therefore, this review will adopt a broader scope.

In addition, it is arguably the case that treatments that are evaluated in populations that suffer from multiple medical and/or psychiatric comorbities have a particularly high bar to clear; adherence interventions that target HIV-infected individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs) are aiming to improve adherence behaviors (and concomitant virologic and immunologic outcomes) in the context of strongly countervailing co-morbidities. Thus, this systematic review examines both positive and negative intervention effects (and at various time points) in order to more precisely understand the mechanisms by which successful interventions target multiple morbidities.

Finally, although thorough literature reviews of adherence interventions for individuals with SUDs exist, several are older and require updating in light of recent intervention results, while others focus primarily on adherence behaviors (but not virologic and immunologic responses of the interventions; 29–38). As a result, this review will provide a current state of the science review.

METHODS

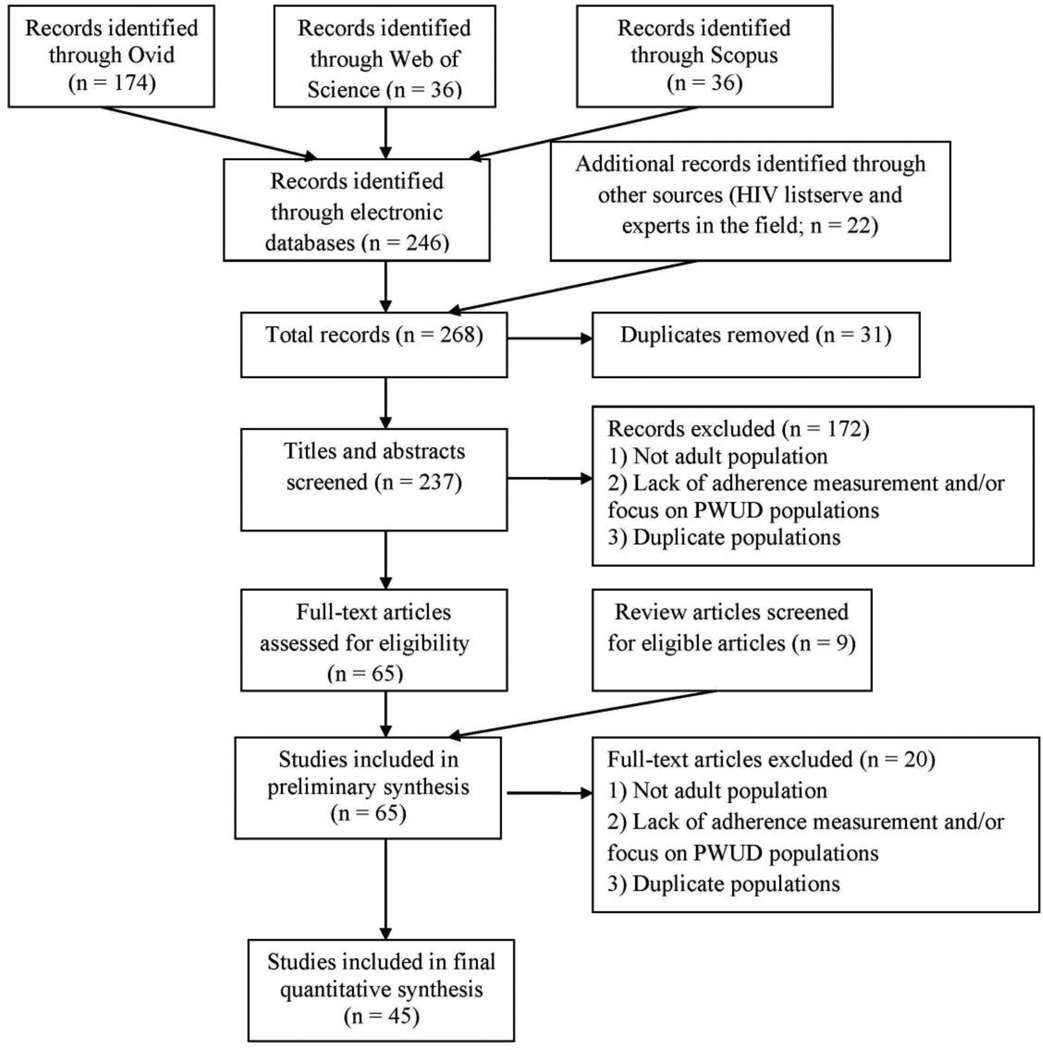

The systematic review was conducted in accordance using PRISMA guidelines [39–40], including a 27-item checklist and a four-phase flow diagram.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies assessing the short- and long-term outcomes of interventions that targeted cART adherence and/or virologic and immunologic outcomes among current and/or past adult drug users were included. Given the strongly linked mediating relationship of adherence to VL [9, 41], the authors included studies that measured either cART or virologic and immunologic outcomes or both. All types of interventions were evaluated, including medication-assisted therapy, psychosocial/behavioral, and integrated medication-assisted therapy and behavioral interventions. Apart from case series studies, almost all study designs were initially considered, including randomized clinical trials, matched studies, quasi-experimental studies, and prospective longitudinal cohorts. Studies that describe known structural impediments, such as repeated incarceration [42] and police harassment [43], which was otherwise not subjected to an intervention, were not included. As cART did not become available until 1996 and guidelines for treatment were not available until 1997, only studies published between January 1997 and July 2011 were considered. Studies involving adolescents, children, or not published in English were not assessed. Trials that did not explicitly and clearly target PWUDs in their recruitment were not included. As such, at least 50% of the subjects in a study must have identified as PWUDs.

All measures of adherence were recorded, including directly administered antiretroviral therapy, pill counts, electronic pill bottle caps (MEMS caps), self-reported recall (e.g., 3-day AIDS Clinical Trials Group), pharmacy refill data, and timeline follow-back method. Adherence behaviors were assessed over a wide range of timeframes, including monthly, 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month. Virologic and immunologic outcomes were typically reported as VL and CD4, respectively. Drug use (current or remote) was defined as the use of any illicit substance (heroin, cocaine, crack, opioids, methamphetamine, and marijuana) or drinking of alcohol.

Information Sources and Search

In order to minimize the bias of missed published interventions, multiple search strategies were implemented (See Figure 1 Flow Chart). Studies were identified through three methods: systematic searches of electronic databases, reviewing reports from HIV listservs, and scanning reference lists of relevant review articles. The first search strategy was applied to the electronic databases OVID, Web of Science, PubMed, GoogleScholar and SCOPUS. Multiple search terms were deployed, reflecting four categories: (1) substance abuse (i.e., alcohol, heroin, cocaine, crack, opioids, methamphetamine, marijuana), (2) medication adherence (i.e., adherence, nonadherence, compliance, noncompliance), (3) study type (i.e., randomized controlled trial, multicenter study, meta-analysis, clinical trial, case control study, cohort study, feasibility study, intervention study, pilot project, sampling study, cross-over study, matched-pair analysis, cross sectional study), and (4) antiretroviral (i.e., highly active antiretroviral therapy, antiretroviral agents, combination antiretroviral therapy, anti-HIV agents). Conference posters and abstracts were excluded. Studies through July 2011 were included. In addition, various relevant HIV listservs were explored for conference abstracts after July 2010, newly published articles, and articles that had been recently submitted for publication. Various experts in the field were consulted to inquire about manuscripts that were in preparation or under review that contained relevant data for this review. Finally, the reference lists of relevant review articles that matched the above search strategy were scanned.

Figure 1.

Flow Chart of Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria of Relevant Articles

Study Selection

One author (MCB) screened records initially by title and abstract for eligibility. The full text of peer-reviewed papers published in English were extracted and included in the systematic review if they met all five of the following criteria: (1) described an adherence-promoting intervention; (2) reported outcome data on adherence and/or viral load and/or CD4; (3) explicitly targeted PWUDs; (4) included individuals 18 years of age or older; and (5) contained a study population in which at least 50% were substance users. Reviews were excluded themselves, but articles from the reference lists that met the above criteria were included. Another author (SK) confirmed or rejected articles based on eligibility criteria. Inter-rater agreement was high. When consensus couldn’t be reached, the third author (FLA) reviewed the article to break the tie. If there was no consensus, authors of the original studies were contacted in order to obtain additional information to assist the third author in adjudicating differing inclusion decisions.

Data Collection Process and Data Items

Standardized data collection forms were used for extraction that included the following information: first author and date published, year of study, study design, study size, demographic characteristics, study location and setting (community, drug treatment facility, correctional facility, methadone program), type of substance abuse, inclusion criteria, description of intervention and control groups (duration, baseline n, treatment type/components), primary outcomes, end intervention effect, post-intervention effect, and impact on adherence and viral load. All extracted data were initially extracted by one co-author (MCB) and then independently assessed by the other two (SK and FLA) who juxtaposed author names to avoid sample overlap between trials and to identify inconsistencies. Again, there was a high level of agreement.

At the conclusion of the data extraction process, studies were divided into three graduated tiers based on rigor of study design. Tier I consisted of randomized clinical trials while Tier II included matched studies such as prospective and retrospective cohort studies and nonrandomized clinical trials. Finally, Tier III incorporated quasi-experimental studies, for instance observational studies, pilots, feasibility studies, and clinical trials and prospective cohort studies without control arms. The three tiers were then subdivided by type of intervention (medication-assisted therapy, psychosocial/behavioral, integrated medication-assisted therapy and behavioral, integrated medication-assisted therapy and HIV care). We focused on the measurement of intervention effects on adherence as well as virological and immunologic outcomes.

RESULTS

Tables 1 – 3 incorporate all included studies, grouped by tiers, and details relevant study characteristics based on the extraction scheme.

Table 1.

Description of Tier 1 Adherence Interventions for HIV-Infected People Who Use Drugs

| Year/Author/ Type of Intervention |

Type of Substance Use |

Intervention Group | Comparison Group | Adherence Measurement |

Retention Rate and/or Follow-up Timeframe |

Adherence Impact | Virological and Immunological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Psychosocial/ Behavioral |

|||||||

| 2005 Samet69 Hybrid: case management and technology |

Current or lifetime history of alcohol abuse or dependence; determined by two or more positive responses to CAGE screening questionnaire |

n = 74; nurse trained in MI addressed alcohol problems, provided a watch with programmable timer to facilitate pill taking, and delivered individually tailored assistance to facilitate medication use (over 3 months in 4 encounters) |

n = 77; usual care (verbal and/or written instructions about optimal medication adherence strategies as part of regular HIV care) |

Self-report ACTG scale; prior 30-day adherence of ≥95% and prior 3-day adherence of 100% (and corroborated with 2 MEMS recordings) |

95% and 88% for short short-term time point in control and intervention subjects, respectively; 58% and 66% for long term time point in control and intervention subjects, respectively |

No significant differences were found at any time point |

No significant differences were found at any time point |

| 2006 Williams70 Misc: home based care |

Active (within the last month) or past illicit substance use (excluding alcohol and marijuana) |

n = 87; Freirian Home- Based Nursing plus standard care (including weekly home visits by nurse and community support worker though month 3; every other week home visits through month 6; and monthly visits through month 12) |

n = 84; standard care (clinic-based care, which might include: review of patient medications, development of medication schedules, identification of strategies to improve adherence, patient education regarding medication dose, side effects, and the need for adherence) |

MEMS (measured in 3-month interval); at baseline, mean adherence was 72% for subjects in the control arm and 69% for those in the intervention arm |

75% of the control arm and 72% of the intervention arm completed 12 months. Because the study closed early, only 51% (48% in the control arm, 54% in the intervention arm) contributed data at 15 months |

At 12 months, 31% of intervention group compared with 22% of control group demonstrated MEMS adherence greater than 90%; at 15 months, 36% of intervention group compared with 24% of control group demonstrated adherence > 90%; difference over time was statistically significant (p = 0.02); when adherence was computed as a continuous variable, there was no difference between the 2 groups in change in adherence over time |

At 12 and 15 months, no significant differences in the proportion of subjects with VL < 400 copies/mL or CD4 > 200 cells/mL |

| 2007 Altice49 DAART |

Heroin and/or cocaine in the previous 6 months |

n = 88; DAART 5 days per week from workers in a mobile health care van over 6 months |

n = 53; self- administered therapy |

Self-report (ACTG over prior 3 days); adherence defined as ≥80% |

63% of patients in the intervention group and 96% of patients in the control group completed 6-months |

Baseline-adjusted adherence outcomes demonstrated greater adherence among patients receiving DAART compared with patients receiving SAT but did not reach statistical significance |

Significantly greater proportion of DAART group (70.5% vs. 54.7%; p = 0.02) achieved either a reduction of 1.0 log10 copies/mL or VL < 400 copies/mL at 6 months; significantly greater mean reduction in VL (1.16 log10 copies/ mL vs. 0.29 log10 copies/ mL; p = 0.03) and mean increase in CD4 (58.8 cells/mL vs. 24.0 cells/mL; p = 0.002) |

| 2007 Macalino50 DAART |

Active substance use (heroin/cocaine use in the past 6 months, other drug use on 4 or more of the last 7 days) or alcohol misuse (positive response on CAGE alcohol screening questionnaire and frequency/ quantity of drinks) |

n = 44; modified DAART (outreach workers attempted visits every day for the first 3 months and tapered them over subsequent months, up to 12 months) |

n = 43; standard of care (SOC) |

Adherence defined as all doses taken over past month; non-adherence defined as missing at least one dose in the prior month |

76 participants; 39 in MDOT and 37 in SOC retained at 3 months |

Not reported | DAART participants were more likely to achieve VL suppression (either VL < 50 copies/mL or > 2 log10-unit reduction in VL from baseline) (OR = 2.16, 95% CI = 1.0–4.7), driven primarily by those cART experienced (OR = 2.88, 95% CI = 1.2 –7.0); overall change in CD4 was greater for individuals on DAART (p = 0.03), with a more pronounced effect among cART- experienced participants |

| 2007 Parsons66 CBT |

Hazardous alcohol drinking (>16 standard drinks per week for men or >12 standard drinks per week for women) |

n = 65; MI and cognitive-behavioral skills building (8 sessions over 8–12 weeks) |

n = 78; time- and content-equivalent educational condition focusing on HIV, cART adherence, and alcohol |

Self-report (timeline follow-back interview over prior 14 days; percent dose adherence and percent day adherence |

83% of the intervention group and 79% of the control group completed the 6-month follow-up visit |

Participants in the intervention condition reported a significantly larger increase in percent dose adherence [F(1, 107) = 4.0; p < 0.05] and in percent day adherence [F(1, 111) = 4.1; p < 0.05] compared with participants in the education condition at 3 months; at 6 months, participants in both conditions reported significant improvements in percent dose adherence (M = 8.2%, SD = 29.4%) and percent day adherence (M = 8.7%, SD = 33.7%) from baseline; difference between the groups was not significant |

At 3-month follow-up, log VL of intervention group decreased from baseline, while log VL of the education condition increased [F(1, 116) = 6.09; p < 0.02]; intervention participants were significantly more likely to demonstrate a 1.0-log reduction in VL (OR = 2.7; p = 0.03) at the 3-month follow-up; at 3- month follow-up, CD4 of intervention condition increased from baseline, whereas CD4 of education participants declined [F(1, 115) = 6.44; p < 0.02; no significant differences between conditions in log VL or CD4 at 6-months |

| 2007 Purcell75 Social support-peer mentoring |

IDU in the past year | n = 486; 10-session peer mentoring intervention over 5 weeks |

n = 480; 8 session video tape (on issues relevant to IDU, including employment, incarceration, overdose prevention, etc.) |

Self-report (number of doses missed over the prior day and week); good adherence was defined as having taken 90% of cART in the prior 7 days |

86% of the intervention group and 84% of the control group attended follow-up visits at 12 months |

Adherence slightly increased over time in both groups (significantly at 6 months [p = 0.03] and 12 months [p = 0.01]); no statistically significant differences between the 2 conditions at any time point |

Not reported |

| 2007 Rosen65 Contingency management |

Cocaine, opioids, cannabis; assessed by toxicology tests breathalyzer, and time- line follow-back calendar describing substance abuse |

n = 28; 16 weeks of weekly CM-based counseling, reinforced for MEMS-measured adherence with drawings from a bowl for prizes and bonus drawings for consecutive weeks of perfect adherence |

n = 28; 16 weeks of supportive counseling |

MEMS, self-report (timeline follow-back and ACTG for prior 3 days and visual analogue scale ratings of the percentage of doses taken in the preceding month) |

18 participants in each group (64%) completed week 32 assessments |

Mean MEMS- measured adherence to the reinforced medication increased from 61% at baseline to 76% during treatment and was significantly increased relative to the supportive counseling group (p > 0.01); participants receiving CM were more likely to achieve 95% adherence during weeks 1–16 than participants receiving supportive counseling (p = 0.02); no significant difference between the two groups for the entire follow-up period |

At week 16, participants receiving CM exhibited significantly improved VL over time compared to those receiving supportive counseling (p = 0.02); differences between groups were no longer significant at week 32 |

| 2010 Feaster74 Social support |

Cocaine, alcohol, cannabis, opioids; determined by DSM- IV criteria for substance use diagnosis within the last year (with cocaine as either the primary or secondary drug of abuse) |

n = 59; Structural Ecosystems Therapy (SET): 4-month intervention focusing on building family support |

n = 67; Psychoeducational HG |

Self report (ACTG Scale over past 4 days); dichotomized as adherent (taking at least 90% of prescribed doses) and non-adherent (taking < 90% of prescribed doses) |

71% of the intervention group and 85% of the control group completed the 12- month follow-up |

Probability of taking prescribed cART was not significantly different across conditions, but SET showed a general decline |

Significant Time* Treatment interaction (B = 77.02, SE = 30.18, p < 0.05) for CD4 but not at the second time point; no significant Time* Treatment effect on VL, although the direction of change was consistent with CD4 results |

| 2010 Petry63 CM |

Cocaine or opioids; determined by DSM-IV criteria for cocaine or opioid abuse or dependence |

n = 89; CM weekly for 24 weeks; patients in the CM group only received chances to win prizes contingent upon completing health activities and submitting substance-free specimens (mean = $260, SD = $267) |

n = 81; Twelve Step (TS) groups for 24 weeks; during the treatment period, both groups received compensation for attendance, submission of urine samples, and completing evaluations at months 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 |

Not reported | Means (SD) of 9.0 ± 6.9 and 10.8 ± 8.1 sessions (of 24 possible) for TS and CM conditions over 24 weeks, respectively; 68 randomized to TS and 77 to CM were retained through 12 months of follow-up |

Not reported | Between baseline and month 6, effects of time were significant, χ2 (n = 162, df = 112) = 159.56, p < 0.002, and the group by time interaction was significant, χ2 (n = 162, df = 146) = −2.66, p < 0.01, with a reduction in VL occurring in CM and an increase in TS participants over time; group by time effects were no longer significant through 12 month follow-up period |

| 2011 Safren84 CBT/(~75% also receiving MMT or suboxone therapy) |

Opioids; endorsed a history of injection drug use and were currently enrolled in opioid treatment for at least one month |

n = 44; cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD); 8 sessions + 1 session on HIV medication adherence (Life-Steps), which involved informational, problem- solving, and cognitive behavioral steps to foster cART adherence |

n = 45; enhanced treatment as usual (ETAU), which also included 1 Life-Steps session |

Measured by MEMS (dose considered missed if it was not taken within a 2-hour window of the designated time); defined as percentage of MEMS-based adherence over prior 1–2 weeks; for follow-up analyses, adherence measured over prior two weeks |

80% in the intervention group and 67% in the control group were followed to 12 months |

At post-treatment, the CBT-AD condition showed significantly greater improvement than ETAU (γslope = 0.8873, t(86) = 2.38, p = .02; dGMA-raw = 0.64); after treatment discontinuation adherence gains were not maintained |

VL did not differ across the two conditions at follow up; however, the CBT-AD condition exhibited significant improvements in CD4 over time compared to ETAU (γslope 2.09, t (76) = 2.20, p = 0.03; dGMA-raw = 0.60) |

|

Integrative Medication- Assisted Therapy and Behavioral |

|||||||

| 2003 Margolin83 MMT plus counseling, case management, group therapy |

IDU, opioid dependence, and abuse or dependence on cocaine; use of heroin and cocaine during the 6-month treatment phase was assessed by urine testing |

n = 45; HHRP received all components of E- MMP and attended twice weekly manual-guided group therapy sessions (addressed the medical, emotional, and spiritual needs of HIV-infected individuals) |

n = 45;E-MMP received 6 months of standard treatment (daily MMT and weekly individual substance abuse counseling and case management) along with a six- session HIV risk reduction intervention |

Self report (timeline follow back that recorded the number of times each day that each cART medication was not taken as prescribed over past week; adequate adherence was defined as ≥95% |

82.2% completed 12 or more weeks; 64.4% completed the 6-month program |

Nonadherence was significantly lower for patients assigned to HHRP than for patients assigned to (p = 0.02); significantly more patients assigned to HHRP+ reported ≥95% adherence during the treatment phase than did patients assigned to E- MMP (HHRP+ = 62.2%; EMMP = 37.5%; OR = 2.74, p = 0.04) |

Not reported |

| 2007 Sorensen85 CM plus MMT |

Cocaine and opioids; assessed by urine testing |

n = 34; medication coaching plus voucher reinforcement for opening MEMS on time over 12 weeks |

n = 32; medication coaching sessions every other week to assist with adherence |

MEMS (2 hours before or after around the scheduled dosage time); pill count (weekly); and self-report (ACTG for prior 3 days); baseline adherence was 51% using MEMS, 75% using pill count, and 75% using self-report |

81% of the control group and 91% of the intervention group remained at the end of follow-up |

Significant mean adherence differences between voucher and comparison groups using MEMS (78% vs. 56%), pill count (86% vs. 75%), and self- report (87% vs. 69%) during intervention; no significant group differences during the follow-up period after vouchers were discontinued |

No significant effects for condition or change over time were seen in VL or CD4 |

| 2010 Lucas80 BPN |

Opioid dependent | n = 46; BPN (clinic- based) with individual counseling |

n = 47; referred treatment (case management and referral to opioid treatment program) |

Months of cART use (via clinical medical records) |

54% of the intervention group and 64% of the control group attended the 12 month follow-up visit |

Use of cART did not differ between groups through 12 months |

Changes in VL and CD4 did not differ between 2 groups from baseline through 12 months |

| 2011 Berg51 DAART plus MMT (STAR*DOT) plus counseling |

Opioid-dependent (based on DSM-IV criteria) but not dependent on alcohol or benzodiazepines; confirmed with urine test |

n = 39; DAART (24 weeks) |

n=38; TAU | Weekly pill counts for DAART; MEMS and pill count for TAU; self- report (ACTG during the prior week); dichotomized self- reported adherence at 100% |

82% of the intervention group and 87% of the control group completed the 24-week intervention |

Adherence in the DAART group was higher than in the control group at all post-baseline assessment points; by week 24 mean DAART adherence was 86% compared to 56% in the control group (p < 0.0001); by end of intervention, differences in adherence diminished by 1 month (55% for DAART vs. 48% for TAU) and extinguished completely by 3 months (49% for DAART vs. 50% for TAU) |

During the intervention, the proportion of DAART participants with undetectable VL (<75 copies/ml) increased from 51% to 71%; HIV RNA in the DAART group decreased 0.52 log10 copies/mL (from 2.74 to 2.22 log10 copies/mL) but remained stable in TAU group; differences in VL between DAART and TAU disappeared by 3 months after the intervention |

| 2010 Wang71 Hybrid: home- based care, technology, MMT (?) |

Active (in the last year) or past heroin addiction |

n = 58; nurse-delivered home visits delivered by 2 nurses every 2 months combined with telephone intervention carried out every 2 weeks by the same nurses who conducted the home visits; adherence counseling, psychoeducation, and MMT (if needed) included in intervention; over period of 8 months |

n = 58; routine care | Self Report (Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS Antiretroviral Medication Self-Report) Questionnaire: 7-day recall period and asks subjects to recall whether they took all (100%), most (80%), about half (50%), very few (20%), and/or none of their pills |

86% of the intervention group and 83% of the control group completed the study |

Compared to those in the control group, participants in the experimental group were more likely to report taking 100% of pills in the previous week (p = 0.0001) and more likely to report taking pills on time than those in the control group after intervention (p = 0.0001) Not reported |

Not reported |

Table 3.

Description of Tier 3 Adherence Interventions for HIV-Infected People Who Use Drugs

| Year/ Author/ Type of Intervention |

Type of Substance Use |

Intervention Group |

Comparison Group |

Adherence Measurement |

Retention Rate and/or Follow-up Timeframe |

Adherence Impact | Virological and Immunological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Medication- Assisted Therapy |

|||||||

| 1997 Antela89 MMT |

Active addiction to heroine |

n = 62; MMT | None | Not reported | Approximately 14 months after MMT initiation |

cART intake increased from 28% to 75% |

Increase in mean CD4 was not significant |

| 2001 Avants44 MMT |

Opioid dependence and cocaine abuse (DSM-IV criteria) |

n = 42; MMT | None | Self-report (timeline follow-back techniques as reported over past week); adherence defined in 2 ways: 1) ratio of sum of missed dose-points to the sum of prescribed dose- points during the first 4 weeks of MMT; and 2) 80% adherence rate (non- adherence ratio of ≤ 0.20); at baseline 36% of patients self-reported < 80% adherence |

Stabilization phase of 4 weeks |

Change in cART non-adherence decreased significantly during the 4-week stabilization phase: Week 1 = 0.25 (.38); Week 2 = 0.11 (.27); Week 3 = 0.11 (.24); Week 4 = 0.10 (.25); F(3,30) = 2.89, p = 0.052 |

Not reported |

| 2006 Palepu47 MMT |

IDU in the previous month |

n = 161; MMT | n = 117 (HIV- infected IDUs not accessing MMT) |

Ratio of number of days of cART prescription refills relative to total number of days of medical follow-up for 12- month period; adherence dichotomized as ≥95% or not |

Accessing MMT at least once during approximate 7-year follow-up period |

MMT was positively associated with adherence (AOR 1.52; 95% CI 1.16– 2.00) |

MMT positively associated with VL suppression (AOR = 1.34, 95% CI 1.00 – 1.79); MMT positively associated with CD4 rise of 100 cells/mL (AOR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.26 – 1.99) |

| 2011 Altice81 BPN |

Opioid dependence (DSM-IV criteria); excluded if investigator- defined alcohol or benzodiazepine abuse |

n = 295; BPN/NLX in HIV clinical care setting |

None | Self-report (and confirmed by chart review) |

Retention on BUP/NX defined as prescription for BUP/NX for three or four quarters (9– 12 months), even if a single prescription during the quarter; 21.7– 28.5% of sample, respectively (approximately 109 subjects prescribed BUP/ NX for three or four quarters) |

Subjects initiating BPN/NLX were significantly more likely to initiate or remain on cART as compared to baseline; improvements were not significantly improved by longer retention on BPN/NLX |

Retention on BPN/NLX for three or more quarters was significantly associated with increased likelihood of achieving viral suppression (b = 1.25 [1.10, 1.42]) for the 64 of 119 (54%) subjects not on cART at baseline compared with the 55 subjects not retained on BPN/NLX |

|

Psychosocial/ Behavioral |

|||||||

| 2000 Bamberger77 Hybrid: counseling, contingency management, technological intervention |

Substance use history (heavy alcohol, crack, injection drug use) |

n = 68; counseling, medication, cash incentives, and e- mail reminders |

None | Not reported | Five months after opening, 62% of the initial clients continued to come in at least once a week |

Not reported | After five months, 76% on cART showed improved viral suppression; of 25 individuals on cART with follow-up VL test, 16 (64%) exhibited VL < 500 copies/mL and 3 (12%) had at least a two-log reduction in VL relative to pre- program levels |

| 2002 Broadhead72 Social support- peer driven |

IDU | n = 14; peer and peer advocate pairs |

None | Pill count by the peer advocate |

Followed for 6 months of weekly meetings; 80% of subjects did not miss regularly scheduled weekly meeting |

For 30 of 36 meetings, the peer’s adherence scores for prior week was ≥80%; overall adherence score for all subjects was 90% |

Not reported |

| 2003 Altice79 Misc: needle exchange |

Active heroine injection |

n = 13; Community Health Care Van (CHCV) at sites of needle exchange; ARV regimens linked to heroin injection timing |

None | All subjects (100%) completed 12-month course of therapy, including needle exchange based health services |

100% followed for 12 months |

Not reported | By 6 months, proportion with VL < 400 copies/mL was 85% (n = 11) and mean VL level decreased from 5.21 log10 copies/mL before initiating cART to 2.38 log10 copies/mL; by 12 months, 54% (n = 7) had a persistently nondetectable VL (< 400 copies/mL) and there was a mean CD4 increase of 150 cells per mL from baseline |

| 2003 Powell-Cope78 Technological |

Current or previous illicit drug or alcohol users according to personal admission or provider |

n = 24; one of three devices: (1) small timer that buzzed at preset intervals, (2) pager reminder that beeped/ vibrated at specified times, (3) Westclox pillbox with an integrated timer |

None | Facilitator-initiated focus group questionnaire; Self- report (ACTG measure); adherence assessed during past 2 weeks and past 1 to 3-month intervals) |

88% were followed to the conclusion of the study at 2 months |

Reminder did not affect the proportion missing a dose in the past two weeks: baseline (33%), first follow-up (30%), and second follow-up (30%) |

Not reported |

| 2005 Parsons67 CBT |

Active illicit drug abuse as determined by DAST-10 score of 6 or greater with heavier drug use than alcohol |

n = 12; combined MI and CBT |

None | Self-report (timeline follow-back technique over prior 14 days) |

73.3% completed all 8 sessions of the intervention within the allotted time frame of 3 months |

No significant differences were found for changes in cART adherence |

Not reported |

| 2005 Mitty57 DAART |

Active substance use (including use of illicit drugs, misuse of prescription drugs, inpatient detoxification, and alcohol abuse) within the past 6 months |

n = 69; DAART- medications delivered by a near-peer outreach worker (ORW) |

None | Self-report (adherence to unobserved doses were logged by ORWs on a daily basis); interviewer- administered questionnaires at 1, 3, and 6 months |

Patients continued in the study regardless of their MDOT status. Fifteen participants (33.3%) received MDOT at all their assessment points. Of the 30 participants who were not receiving MDOT at all assessment points, 11 were not receiving MDOT at 1 month, 22 at 3 months, and 26 at 6 months. 10% of participants reengaged in the program |

Not reported | Individual decrease in VL from baseline to 6 months among DAART participants was 2.7 log10 copies/mL |

| 2008 Ma55 DAART |

History of substance use defined as meeting one or more of the following: (1) used cocaine/ crack or heroin in the past 6 months, (2) used marijuana more than 4 times per week in the past 6 months, and (3) used alcohol in the past 30 days (and endorsed at least one of four CAGE questions) |

n = 31; DAART- outreach worker observed medication intake |

None | Self-report (dividing number of missed doses by the number of total prescribed doses over a 4 day period); dichotomized as < or > 80%; at baseline, none of the participants met the 80% criterion for adherence to cART regimen |

77% completed the intensive phase at 3 months and 68% completed the transition phase at 6 months |

75% of the participants met the 80% adherence criterion at 3 months and 67% met the 80% adherence criterion at 6 months |

39% of participants had VL < 400 copies/mL at baseline, 55% at 3 months and 67% at 6 months |

| 2009 Deering73 Social support- peer driven |

Current IDU, including stimulants (cocaine, crack cocaine, crystal methamphetamine) and/or opiates (heroin, morphine or dilaudid); currently smoked drugs (including cocaine, crack cocaine, heroin, crystal meth) |

n = 20; Peer Driven Intervention (PDI): weekly peer support meetings, health advocate (buddy) system, peer outreach service, and onsite nursing care |

None | Pharmacy records and self-report (over prior week) |

Participants attended an average of 50 (21–70) PDI meetings over 6–12 months |

Overall mean pharmacy record adherence = 88% per PDI-week; overall mean self- reported adherence = 92%; mean adherence increase across sample = 18% |

Number of VL tests ≤ 50 copies/mL increased by 40% from the pre-PDI period (1 year before enrollment) to the PDI period (duration enrolled) |

|

Integrative Medication- Assisted Therapy and Behavioral |

|||||||

| 1998 Sorensen61 DAART plus MMT |

Opioid dependent | n = 12; on-site dispensing of cART and individualized medication management |

None | Nurse’s drug monitoring log, self-report, and MEMS |

100% remained in the study though study completion (8 weeks of intervention and 4 weeks of post- intervention follow-up) |

Baseline-to-follow- up self report of improvement was significant at Week 4, 8, and 12 (4 weeks after intervention end) follow-up periods; per self-report, cART taken averaged above 80%; MEMS percentages declined during the four follow-up weeks |

Not reported |

| 2002 Clarke58 DAART plus MMT |

Active IDU (injecting heroine at least once daily) |

n = 39; DAART | None | Not reported | 90% remained at 3 months, 79% at 6 months, and 73% at one year |

Not reported | Mean CD4 change from baseline were significant at 3, 6, and 12 months; at 48 weeks, 51% of cART-experienced patients and 65% of cART-naïve patients achieved maximum viral suppression (VL < 50 copies/mL) |

| 2004 Conway59 DAART plus MMT |

IDU; measured by urinalysis |

n = 54; MMT and cART dispensed daily as DAART |

None | Not reported | Median follow-up for 54 subjects was 24 months (range, 5–58 months) |

Not reported | After median of 24 months, 17 of 29 patients in the once- daily cART group and 18 of 25 in the twice-daily cART group exhibited VL < 400 copies/mL; both groups exhibited significant increases in CD4 from baseline (once- daily group: 190 cells/mL at baseline vs. 290 cells/mL at follow-up (p < 0.01); twice-daily group:140 cells cells/mL at baseline vs. 290 cells/mL at follow-up (p < 0.005)) |

| 2007 Lucas62 DAART plus MMT |

Methadone maintenance; active opiate drug use determined by urine screens |

n = 88; DAART | None | Supervised dosing and self-report (of non- supervised dosing); non- adherence with supervised dosing was defined as < 80% |

Study subjects participated in the DAART intervention for a median of 9.4 months (IQR 4.6– 16.8) |

Median participant adherence with supervised dosing was 83%; median self-reported adherence with unsupervised doses = 99% |

23 patients (29%) exhibited ≥ 1 measurement of virologic failure (VL > 400 copies/mL) over intervention course (median length = 9.4 months); observed adherence with supervised doses was significantly associated with virologic failure |

| 2008 Kapadia90 Drug abuse treatment with or without medication |

Engagement in (illicit) drug use at baseline or during follow-up visits |

n = 573; drug abuse treatment program with or without medication |

None | Self-report (< 95% vs. ≥ 95%) |

Participants included in the present study provided information for up to five years (ten follow-up visits) |

Individuals accessing any drug abuse treatment program were significantly more likely to report adherence to cART ≥95% of the time (AOR = 1.39); medication-based or medication-free programs were similarly associated with improved adherence |

Not reported |

| 2011 Cunningham31 MMT (also incorporates onsite HIV and primary medical care, drug abuse and mental health treatment services) plus STAR Program (MI and CBT Skills) |

Drug use in the last 3 months: Cocaine, crack, heroin, club drugs (crystal meth, ecstasy, special k), unprescribed pain pills or benzodiazapines, regularly three or more alcoholic drinks a day |

n = 315; STAR Program- MI and Cognitive Behavioral Skills Techniques |

None | Self-report (during past 3 days, week and month) |

3 month follow-up data includes 31% of enrolled participants as intervention is in progress |

A smaller percentage of patients missed any cART doses during past 3 days (30.8% vs. 18.5%, ns) or in the past week (42.1% vs. 28.0%, ns) 3 months after STAR Program enrollment as compared with baseline |

VL significantly decreased (median VL = 3.7 log10 copies/mL vs. 3.2 log10 copies/mL; p < 0.01) from baseline to 3 months for those in STAR Program |

LEGEND: CM = Contingency Management; DAART = Directly Administered Antiretroviral Therapy; MI = Motivational Interviewing; CBT = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; TAU=Treatment as Usual; MMT = Methadone Maintenance Treatment; VL = HIV RNA Viral Load; CD4 = CD4 lymphocyte count; BPN = buprenorphine; BPN/NLX= buprenorphine/naloxone; MEMS = Medication Event Monitoring System; ACTG = The AIDS Clinical Trials Group Adherence Questionnaire; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy; MDOT= Modified Directly Observed Therapy; SAT= Self-administered therapy; STAR Program= Substance abuse treatment and recovery program

Medication-Assisted Therapy Interventions

There were no Tier 1 interventions solely evaluating medication-assisted therapy (MAT) to foster HIV treatment adherence among PWUD populations. Despite this, there were several good quality studies that addressed the effect of MAT on HIV treatment adherence and markers of HIV progression. Avants et al. [44] reported significant increases in self-reported medication adherence among 42 HIV-infected IDUs beginning methadone maintenance treatment (MMT), while other studies indicated that buprenorphine (BPN) maintenance treatment increased adherence to cART regimens [45] and may keep VL and CD4 relatively stable at short-term follow-up [46].

Prospective longitudinal data confirmed findings described earlier. In a longitudinal prospective cohort of opioid dependent, HIV-infected IDUs, MMT provision was independently and significantly associated with increased adherence, more rapid uptake of cART, viral suppression and CD4 increases [47]. A 5-year longitudinal study of opioid substitution treatment (OST), including BPN and methadone, with cART experienced opioid-dependent individuals concluded that retention in OST was significantly associated with long-term virological success [48]. This association held even after adjustment for significant predictors (such as adherence) of long-term virological success.

Behavioral and Psychosocial Interventions

Directly Administered Antiretroviral Therapy (DAART)

Three independent DAART RCT trials [49–51] consistently showed significantly higher rates of cART adherence, improved virologic functioning, and increased CD4 counts among DAART participants compared to control groups at short-term follow-ups. Successful virologic outcomes after DAART discontinuation, however, remain more equivocal, with some interventions demonstrating maintenance of these gains and others not.

In the largest RCT, Altice et al. [49], compared 6-month DAART to self-administered therapy (SAT) among 141 HIV-infected drug users (cocaine and/or heroin). Both for virologic and immunologic outcomes, the DAART arm was statistically superior to the SAT arm, both at intervention end and at 6-month follow-up. Similar results were seen in subgroup analyses stratifying the patients by virologic suppression at baseline. There was a trend toward greater adherence among patients receiving DAART as compared to SAT, but this did not reach statistical significance. The virological outcomes did not persist, however, over the subsequent six months of follow-up after DAART was terminated [52].

Macalino et al. [50] randomized 87 HIV-infected drug users [broadly defined as heroin/cocaine/alcohol use in the past 6 months, other drug use on four or more of the last seven days, or alcohol misuse (positive response on the CAGE alcohol screening questionnaire)] to receive either modified DAART or standard of care. At the end of 3 months, DAART participants were more likely to achieve VL suppression or a >2.0 log reduction than controls, a result driven primarily by those individuals who had previously received cART. Findings for CD4 were largely consistent with the virologic outcomes: mean CD4 at month 3 was higher in the DAART than the control arm, an effect that was primarily driven by cART-experienced individuals.

One study reported favorable virologic and immunologic results as well as improvements in cART adherence in response to an intervention that formally integrated DAART into a MMT program. Berg at al. [51] compared DAART to SAT among 77 HIV-infected MMT opioid users during 24 weeks. Over the course of the trial, patients in the DAART arm consistently displayed significantly higher adherence rates than the SAT group, while VL in the DAART group decreased 0.52 log10 copies/ml and remained stable in the SAT group. Effects were more pronounced for those demonstrating baseline detectable VL.

Follow-up of the trial indicated that benefits of DAART ceased after it was terminated [53]. Results from a post-trial cohort study of 65 individuals who had completed the initial 24-week trial suggested that after DAART ended, differences in adherence diminished by 1 month and extinguished completely by 3 months. Similarly, differences in VL between the DAART and SAT groups returned to baseline within 3 months after intervention termination, as did the proportion of DAART participants with undetectable VL within each group. Finally, a significant relationship between counseling and cART adherence was reported among a subset of individuals (n=22) who received 6 individual counseling MI/CBT sessions over the course of a 12-month period after the 24 week DAART trial ended [54]. No significant association between cumulative adherence counseling hours and post-counseling and VL, however, was found.

Second tier data also suggest promising outcomes for DAART in improving virologic outcomes among heterogeneous populations, including African American HIV-infected PWUDs [55], treatment-naïve HIV-infected IDUs in Italian prisons [56], and HIV-infected cART experienced PWUDs [57]. Second and third tier data for interventions that incorporated both DAART and MMT were somewhat consistent with data from the Berg et al. [51] trial, although suggested persistence of virologic and immunologic improvements at longer-term follow-up points. A prospective observational study among MMT HIV-infected IDUs demonstrated that a majority of patients (both cART naïve and experienced) achieved maximum viral suppression as well as significant incremental mean CD4 changes from baseline over 12 months of treatment [58]. Other long term-follow-up data indicated that a significant majority of MMT patients who received DAART were more likely to exhibit VL<400 copies/ml after 24 month follow-up as compared to baseline [59] and to achieve viral suppression through 12 months than were patients in comparison groups [60]. Finally, Sorensen et al. [61] reported marginal short-term improvements in adherence behaviors in the DAART arm compared to standard care participants, but the modest gain and group differences disappeared within one month after intervention completion. Virologic and immunologic outcomes, however, were not reported. It should be noted that it was difficult to draw conclusions from several MMT/DAART trials (e.g., [62]) as they reported a relatively small proportion of supervised cART doses in many patients.

Contingency Management

All 3 contingency management studies [63–65] converged on similar results and demonstrated short-term improvements in cART adherence, but none showed persistence after vouchers were discontinued. Petry et al. [63] compared weekly CM or 12 Steps (TS) groups for 24 weeks among 170 HIV-infected patients with cocaine or opioid use disorders. From pre- to post-treatment, CM participants showed greater reductions in VL than TS participants, maintaining significant effects after controlling for duration and study group of interaction, with VL reduction among CM subjects and VL increase among TS participants. These effects, however, were not maintained throughout the 12-month follow-up period.

Rigsby et al. [64] randomized 55 HIV-infected subjects (the majority of whom had histories of heroin or cocaine use) to 4 weekly sessions of either nondirective inquiries about adherence (control group), cue-dose training (CD), or cue-dose training combined with cash reinforcement for correctly timed bottle opening (CD-CR). Results indicated significant improvement in adherence for the CD-CR but not for the CD group (as compared to the control group) during the active training period. By using week 4 adherence as a covariate, however, there was a significant decrease in adherence over time in the CD-CR group. Mean VL change from baseline through 12-week follow-up was not statistically significant different between each of the training groups and the control group.

Rosen et al. [65] built on the earlier Rigsby et al. [64] trial by lengthening the number of weeks individuals received treatment. Within the context of this new trial, 56 HIV-infected participants with SUDs and suboptimal adherence to cART were randomly assigned to 16 weeks of weekly CM-based counseling or supportive counseling, followed by 16 additional weeks of data collection and adherence feedback to providers. Mean adherence to cART was significantly increased relative to the supportive counseling group during the 16-week treatment phase. Though virologic outcomes were also improved in the immediate post-intervention aftermath for the CM group, differences between groups on adherence and VL outcomes were no longer significantly different after 16 weeks of observation.

Counseling Using Motivational Interviewing (MI) and/or Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment (CBT)

One RCT and 2 pilot trials using MI/CBT reported good short-term gains in cART adherence but limited efficacy in sustaining adherence improvement and VL reduction at follow-up points [66–68]. In a RCT of 143 HIV-infected hazardous alcohol drinkers assigned to an 8-session MI/CBT intervention or a time- and content-equivalent educational condition, participants in the MI/CBT group demonstrated statistical (but not clinically significant) decreases in VL (at least a 0.5 log reduction), significant increases in CD4, and significantly greater improvement in cART adherence at the 3-month follow-up compared to the education condition [66]. None of the outcomes were sustained, however, at the 6-month visit.

Data from two pilot trials are largely consistent with the Parson’s 2007 RCT. Improvements in cART adherence were demonstrated for pilot trials incorporating MI plus feedback and skills building and MI/CBT through 3–6 months [67–68]. These data, however, must be interpreted cautiously as one was an uncontrolled trial [67] and the other reported no significant between-groups effect for cART adherence between the MI and the control video education groups at any time point [68]. Similarly, there were no statistically significant main or between- group effects for the interventions on VL reductions or the proportion of participants with viral suppression.

Nurse-Delivered Multi-component Interventions

Three strong, high quality RCTs have incorporated nurse-delivered multi-component interventions [69–71]. The data from the 3 trials consistently indicate improvements in viral suppression and cART adherence in the short term, but the benefits do not persist. The interventions were multi-component, incorporating many different treatment elements that are described below.

Samet et al. [69] conducted an RCT of a multi-component, nurse-delivered intervention to each participant to promote cART adherence and compared it to routine medical follow-up (including written or oral instructions about optimal medication adherence strategies) among 151 HIV-infected individuals with alcohol use disorders. Nurses trained in MI delivered the intervention over 3 months in 4 encounters (including a home visit) and included: addressing alcohol problems; providing a watch with a programmable timer to facilitate pill taking; promoting treatment self-efficacy; and delivering individually tailored assistance to facilitate medication use. No significant differences in medication adherence, CD4, or VL were detected after 6 or 12 months.

Results from the Williams et al. [70] and Wang et al. [71] counseling studies are consistent with the Samet et al. [69] trial despite the difference in treatment length and dose/intensity, substance abuse eligibility criteria, and geographical location. The Williams et al. [70] trial evaluated the efficacy of a 1-year home-visit intervention and compared it to usual care among 171 HIV-infected adults. The intervention team, consisting of a nurse and a community support worker, encouraged subjects to identify individual and social factors that they perceived as influencing their success with cART adherence. Usual care was variable and consisted of assistance with the development of medication schedules and strategies to improve adherence and/or patient education regarding medication dose, side effects, and the need for adherence. The proportion achieving >90% adherence in the intervention group through 15-month follow-up was statistically significant, yet when computed as a continuous variable, there were no differences between the 2 groups in change in adherence, VL, or CD4 count at 12 and 15 months.

In a replication study, Wang et al. [71] randomized 116 HIV-infected active or past heroin injectors to receive nurse-delivered home visits combined with telephone intervention over 8 months in China, while the control group received routine care. The home visits, expanded on in prior work [70], added semi-structured telephone calls to enforce the home visits. Routine care, however, was not described. After eight months, participants in the experimental group were significantly more likely to self-report taking 100% adherence, yet the study was limited by lack of virologic or immunologic outcomes.

Social Support and Peer-Driven Interventions

Preliminary peer-driven interventions have suggested some initial promise in fostering improved short-term treatment adherence among HIV-infected stimulant and opioid users [72–73]. Longer term assessments in RCTs, however, suggest that improvements in adherence delivered through peer-driven or family support interventions may subside or decline over time.

Feaster et al. [74] conducted a RCT comparing Structural Ecosystems Therapy (SET), a 4-month intervention focused on building family support for relapse prevention and HIV medication adherence, to a psychoeducational Health Group (HG) in 126 HIV-infected women in recovery. SET participants, compared to HG, demonstrated no impact on VL, declining medication adherence, but a statistically significant increase in CD4 count at 12 months, primarily related to an increased proportion of SET participants receiving cART.

Purcell et al. [75] compared a 10-session peer mentoring intervention to an 8-session video discussion intervention (control condition) among 966 HIV-infected IDUs recruited in 4 US cities. Throughout 12-months of observation, there were no differences in adherence between the 2 conditions at any time point, and biological outcomes were not measured.

Educational Counseling

Educational counseling interventions targeting cART adherence among PWUDs are limited. One 5-month pilot observation study among a sample of primarily HIV-infected African American IDUs with documented cART non-adherence suggested that a brief intervention incorporating medication adherence psychoeducation counseling sessions with multi-compartment weekly pill organizers showed a significant increase in adherence, medication refills, and clinic appointments compared to baseline [76].

Adherence Case Management (Medication Management, Counseling, Incentives, Electronic Reminder)

Data for adherence case management programs are limited. One small community-based program reported that 16 of 25 (64%) patients receiving cART and case management for at least 2 months exhibited viral suppression, yet neither adherence was reported nor was there a comparison group [77].

Timer/Reminder Interventions

There are few efficacy data regarding the use of pager or timer-reminder interventions to promote cART adherence among PWUD, though they are suggestive at improving virologic suppression. One small study indicated that although well-accepted by participants and fairly feasible to implement, timer/reminders did not improve cART adherence among HIV-infected illicit drug and alcohol users after 1 and 2 month follow-ups [78]. In another small pilot study for out-of-drug treatment HIV-infected IDUs at mobile healthcare sites, viral suppression was achieved by 85% at 6 months, 77% at 9 months, and 54% by 12 months [79] when adherence was linked to injection practice reminders.

Integrated Medication-Assisted Therapy and Behavioral Interventions

The following section reports on the results of interventions that integrate medication-assisted therapies, such as with methadone or buprenorphine, various behavioral or psychosocial interventions, or other systems of care to improve HIV treatment outcomes. These interventions are limited to one RCT, pilot data, or examination of only adherence or only virologic and immunologic outcomes [31, 80–82].

Integrating Medication-Assisted Therapy with HIV Treatment

Trials targeting the integration of medication-assisted therapies into HIV primary care have shown initial promise in improving HIV treatment outcomes. In the only identified RCT, Lucas et al. [80] conducted a 12-month RCT in which clinic-based treatment with buprenorphine and individual counseling was compared to case management and referral to an opioid treatment program among 93 HIV-infected, opioid-dependent subjects. Those with integrated care were significantly more likely to receive substance abuse treatment, but there were no significant changes from baseline in VL and CD4 between the study arms with respect to adherence to cART, VL, and CD4 counts.

In a much larger observational cohort, Altice et al. [81] reported that longer retention on buprenorphine treatment was significantly associated with increased likelihood of initiating cART, and improving CD4 counts for the entire cohort. It was not, however, associated with improved virological suppression, primarily due to the large proportion already on cART at baseline and high levels of virological suppression. Another study integrating BPN into HIV clinical care settings resulted in increases in initiation of cART and CD4. Among a subset of individuals who were not on cART at baseline, retention on BPN for 6 to 12 months resulted in an increased proportion of subjects with viral suppression compared to those who received BPN for shorter durations. When the analysis was limited to those not on cART at baseline, longer retention on BPN was significantly associated with higher levels of viral suppression compared to those with shorter BPN retention. Small pilot studies integrating BPN into HIV treatment settings suggest improvements in adherence and CD4 and trends in VL improvement at 3 and 6 month follow-up time points for those receiving integrated BPN and HIV care [31, 82].

Methadone Maintenance and Risk Reduction Counseling Treatment

Margolin et al. [83] randomized 90 HIV-infected IDUs receiving MMT to a 6-month behavioral intervention, the Holistic Health Recovery Project (HHRP+), or to an active enhanced MMT control that included harm reduction components recommended by the National AIDS Demonstration Research Project. Significantly more patients assigned to HHRP+ reported >95% adherence during the study treatment phase than did patients assigned to control group. Virologic changes as a result of the intervention were not examined in the trial.

Methadone Maintenance and CBT/MI Counseling

Safren et al. [84] conducted an RCT of an 8-session CBT intervention that addressed both cART adherence and depression (compared to enhanced control group of 89 opioid dependent, depressed HIV-infected patients receiving MMT). The control group included physician assessments and MEMs cap reading. At the end of treatment, the intervention arm had significantly greater cART adherence and reduction in depression compared to controls. Although depression gains were sustained, neither adherence nor virological outcomes persisted at 6 and 12-months.

Methadone Maintenance and Medication Coaching/Voucher Reinforcement

Sorensen et al. [85] randomized 66 HIV-infected MMT patients to 12 weeks of medication coaching plus voucher reinforcement for opening electronic medication caps on time versus a control of medication coaching only to assist with adherence. Though the intervention resulted in improved adherence, there were no statistically significant effects for either VL or CD4. Consistent with other contingency management trials, the differences in adherence disappeared between the groups when the vouchers were discontinued.

DISCUSSION

The current review was undertaken to provide an updated review of the scientific evidence for interventions that promote cART adherence among HIV-infected PWUDs. Current findings support several cART adherence interventions among PWUDs, including immediate improvements in adherence and virologic suppression. The best data support DAART alone and DAART integrated within MAT programs. Indeed, three strong DAART RCT trials showed evidence for significant VL or CD4 improvements during the intervention period when compared to controls, including when DAART is integrated within MMT [49–51]. The long-term persistence associated with DAART, however, is not supportive as a stand-alone intervention [52–53] and likely requires longer-term treatment, transitional programs, or booster sessions. The single arm longitudinal studies support sustained viral suppression and incremental CD4 increases over 12 [58] and 24 [59] months of treatment, yet this suggests that patients may need this level of intervention for a lifetime unless transitional interventions prove effective. Other studies have supported the limited post-treatment effects of DAART [86].

Although clinically intuitive, DAART interventions are labor-intensive and costly to implement. Although DAART trials have been shown to be cost-effective for various health conditions, including multidrug-resistant tuberculosis [87], the feasibility of implementing these interventions on a large scale and over a sustained time period is uncertain for life-long cART regimens. Nevertheless, in settings capable of implementing them, DAART interventions show the strongest intervention effect among non-adherent PWUDs. They have not, however, been studied among cART-naïve patients who have not yet demonstrated non-adherence and may prove beneficial in the short-term for this population. Cost-effectiveness analyses need be undertaken to evaluate the fiscal circumstances and cost-benefit ratios in order to optimize the implementation of DAART treatments for HIV-infected populations in various international and domestic regions where resources remain constrained.

Although quite different in theoretical orientation and intervention content, nurse-delivered multi-component interventions and contingency management treatments were not as consistent as DAART interventions, but, overall, resulted in non-sustained benefits in the few trials where an intervention effect was found [63–65, 69–71]. By end of treatment and/or follow-up, differences between groups in adherence and viral load were no longer significantly different. Additional research efforts should aim to design contingency management or nurse-delivered multi-component interventions that extend the adherence and virologic effects of the interventions. In light of the current findings, however, there are insufficient data to fully support multi-component interventions or contingency management as long-term adherence strategies, yet RCTs are currently underway.

Although there are promising data from pilot trials, the efficacy of educational counseling, adherence case management, timer/reminder, peer-driven and family support interventions to promote cART adherence among PWUDs have not been established. For example, although preliminary pilot peer-driven and family support interventions have reported somewhat favorable trends in cART adherence gains [72–73], the longer assessment timeframes traditionally captured in RCTs indicated that improvements in adherence as a function of peer-driven or family support interventions gains may subside over time. More conclusive larger-scale trials are needed to evaluate the potency of these interventions.

Though the findings for the integration of MAT into HIV treatment is generally supportive of improving HIV treatment outcomes, RCTs have yet to be fully conducted. Uncontrolled trials consistently showed increases in adherence [42], likelihood of prescribing cART, viral suppression, and CD4 [47, 82] in individuals receiving MAT. In addition, data supports improvements in cART adherence and stable VL and CD4 at short-term follow-ups among populations treated with BPN [45–46] and long-term virologic success with retention in OST care [48]. The only RCT [80] to date that evaluated the integration of buprenorphine into HIV clinical care settings did not indicate improvement in cART adherence or virologic and immunologic outcomes, although this is best explained by the high proportion of subjects already prescribed and adherent to cART at baseline.

The degree to which behavioral interventions potentiate the effects of ongoing MAT should be explored further. Three RCTs integrating MMT and various behavioral interventions [83–85] displayed short-term adherence gains but none support long-term virologic suppression. Additional rigorous trials on the clinical efficacy of integrated MAT and behavioral interventions for cART adherence and relevant HIV clinical outcomes for HIV-infected PWUD populations are urgently needed.

Of great concern is that none of the adherence interventions among PWUDs, in general, demonstrate long-term, post-intervention HIV treatment outcomes. One of the central tenets for the future success of the “seek, test, treat, and retain” and “treatment as prevention” paradigms is to foster and maintain HIV treatment adherence among vulnerable populations, such as PWUDs. Because HIV is a chronic, life-long illness, interventions meant to facilitate durable adherence to cART regimens will likely need to include ongoing booster sessions to promote and maintain adherence behaviors or to initiate them before a patient has entered into significant patterns of non-adherence. Furthermore, interventions that simultaneously target drug abuse as well as non-adherence may provide more long-term success, as attempting to substantively modify adherence patterns in the absence of concomitantly treating drug abuse may be difficult.

An intuitive and unique potential platform for the delivery of ongoing, sustained and long-term HIV adherence care may be through the use of mobile technologies. Given their relative low cost and wide penetration across the US and most international settings, albeit with uncertain acceptability among PWUDs, mobile technologies (e.g., cell phone, smart phones) may offer new opportunities for long-term adherence monitoring and intervention. Future research efforts should focus on evaluating the acceptability, feasibility, clinical efficacy, and cost-effectiveness of technologically-delivered interventions that range the gamut, from those that include elements of CM, CBT, MI, DAART (through video). Various technologies and the applications they support, including short message services, real-time, global positioning system, connectivity to the internet (and educational and social support services) allow for an unprecedented opportunity to provide interventions in “real time” (in response to missed HIV doses, heightened drug cues) and over a longer sustained timeframe (if only to provide booster sessions) than has previously been possible. Future research can also identify subpopulations among PWUDs for whom certain technologies and/or mode of communication with providers or peers may be preferred and/or most efficacious. Multiple potential funding mechanisms within the National Institutes of Health place emphasis on the development and evaluation of these technologically-delivered interventions for PWUDs (e.g., Program Announcement: PA: 12–117 and 12–118).

Though an exhaustive review of cART adherence interventions were assessed, limitations remain. First, the authors narrowly limited the HIV treatment outcomes to adherence, viral suppression, and immunologic outcomes. Structural interventions, such as changes in drug policy, reducing incarceration or community-based policing, were not empirically tested and therefore not included. Outcomes relating to substance abuse treatment, engagement and retention in care, mortality, and resistance, while important, were not the target of this review. Additionally, although the authors deployed a comprehensive set of search strategies to identify relevant articles, it is possible that the authors overlooked some articles, potentially biasing the interpretations and discussion. Finally, there was no quantification of intervention effects, with this review solely focusing on reporting general trends in the literature. One of the challenges for this review, as noted by others [29, 88], is the inconsistency and lack of uniformity in the reporting of important dependent variables across the reviewed studies. For example, past experience with cART regimens was often not elucidated in trials nor was any potential differential effect of interventions on cART-naïve versus cART-experienced participants. Substance abuse disease severity was usually underreported and/or highly heterogeneous across samples, including definitions of abuse versus dependence. Virologic and immunologic markers of disease severity as well as cART rates were often missing at baseline for included samples, so the degree and robustness of any given intervention’s effect was difficult to quantify. Moreover, adherence was measured over differing time frames (e.g., daily, past week, month), during differing time periods (e.g., 4, 6, 12 or 24 months) and with various adherence thresholds (mean, >90, >95%). To the extent possible, a more consistent approach to reporting and data analysis is required in order to make more meaningful inferences across trials.

CONCLUSION

Recent guidelines, using rigorous techniques for classifying the quality of trials, provide the strongest support for DAART to support cART adherence among PWUDs. Within this review, however, there are a number of other potentially promising options that require further investigation; they should be reassessed with booster sessions, in cART-naïve PWUDs, and subjected to longer-term evaluation. In order to achieve the benefits needed to reduce HIV transmission and effectively reduced HIV-related mortality, such interventions will ultimately need to be efficacious, effective in real-world settings, and result in sustainable viral suppression.

Table 2.

Description of Tier 2 Adherence Interventions for HIV-Infected People Who Use Drugs

| Year/ Author/ Type of Intervention |

Type of Substance Use |

Intervention Group | Comparison Group | Adherence Measurement |

Retention Rate and/or Follow-up Timeframe |

Adherence Impact | Virological and Immunological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Medication- Assisted Therapy |

|||||||

| 2000 Moatti45 BPN |

IDU | n = 32; BPN ambulatory DMT |

n = 132 ex-IDU; n = 17 IDU not on DMT |

Nurse-administered questionnaire asking about number of daily pills taken during the week prior to the visit (non-adherent classified as < 80%) as well as a self- administered questionnaire (non- adherent if admitted that they have not been “totally adherent”) |

Not reported | 107 of 164 patients (65.2%) could be classified as fully adherent with cART as classified by the nurse- administered questionnaire; active IDU were ~5 times more likely to be non- adherent than IDU on DMT and ex-IDU; IDU on DMT had higher adherence than ex- IDU, although this difference did not reach statistical significance |

Non-adherent patients had significantly higher median VL (3.9 log10 copies/mL vs. 2.7 log10 copies/mL); median decrease in VL before and after initiation of cART was significantly lower among non- adherent (−0.53 log10 copies/mL) as compared to adherent patients (− 1.04 log10 copies/mL) |

| 2009 Roux48 BPN or MMT |

Dependent on opioids; validated through urine tests |

n =53 BPN; n=28 MMT |

n = 32; no OST | Self report (ACTG Questionnaire); patients were considered “adherent” if they reported that they had taken 100% of the total dose of prescribed drugs during the previous month |

Median duration of OST was 25 months (range, 3–42 months) |

52.2% were 100% adherent at baseline; over the course of 5 year longitudinal study, 48.4% mean adherence |

Patients who received BPN or MMT while on cART had a 2–4 fold increased likelihood of virological success when compared with patients who did not receive OST; retention in OST (median duration = 25 months) was significantly associated with long- term virological success (OR = 1.20 per 6-month increase, 95% CI = 1.09 –1.32) |

| 2010 Springer46 BPN |

Opioid- dependence (DSM-IV criteria) |

n = 23; BPN/NLX | SAT | Not reported | 74% for all 23 subjects and 81% for the 21 who completed induction |

Not reported | Proportion with a non- detectable VL (VL<400; 61% vs. 63% log10 copies/ mL) and mean CD4 (367 vs. 344 cells/mL) was unchanged at 12 weeks as compared to baseline |

|

Psychosocial/ Behavioral |

|||||||

| 2000 McPherson- Baker76 Hybrid: counseling and technological intervention |

Past or current history of substance use; identified by patient chart data |

n = 21; monthly medication counseling and weekly medication pill organizer |

n = 21; matched controls receiving standard pharmacy care including review of medications |

(1) number of prescribed medications refilled; (2) number of missed clinic appointments; (3) number of hospitalizations; and (4) number of opportunistic infections |

Not reported | Significant increase from baseline to 5 months post- intervention with HIV- related medication refills (pre-intervention refill compliance = 46.7% vs. post- intervention refill compliance = 75.8%) and clinic appointments (pre- intervention visit compliance = 56.7% vs. post intervention visit compliance = 76.1%) |

Not reported |

| 2000 Babudieri56 DAART |

IDU | n = 37; cART administered by prison nurses (DAART schedule) |

n = 47; nurses left drugs with patient once a day with no directly observed control (NDOT schedule) |

Not reported | 95% of intervention group remained in study |

Assumed to be 100% (but not reported) |