Abstract

The results of three selective adaptation experiments employing nonspeech signals that differed in temporal onset are reported. In one experiment, adaptation effects were observed when both the adapting and test stimuli were selected from the same nonspeech test continuum. This result was interpreted as evidence for selective processing of temporal order information in nonspeech signals. Two additional experiments tested for the presence of cross-series adaptation effects from speech to nonspeech and then from nonspeech to speech. Both experiments failed to show any evidence of cross-series adaptation effects, implying a possible dissociation between perceptual classes of speech and nonspeech signals in processing temporal order information Despite the absence of cross-series effects, it is argued that the ability of the auditory system to process temporal order information may still provide a possible basis for explaining the perception of voicing in stops that differ in VOT. The results of the present experiments, taken together with earlier findings on the perception of temporal onset in nonspeech signals, were viewed as an example of the way spoken language has exploited the basic sensory capabilities of the auditory system to signal phonetic differences.

In the last few years, there has been a great deal of interest in the mechanisms thought to underlie the perception of speech sounds, particularly as they may be used in processing distinctions involving the phonetic features of voicing, place, and manner in consonants. Beginning with the initial report by Eimas and Corbit (1973), numerous studies have used the selective adaptation technique to provide support for the hypothesis that complex feature detectors mediate speech perception (see Ades, 1976; Cooper, 1975; and Eimas and Miller, 1978, for reviews). These detector mechanisms were thought to be narrowly tuned to specific acoustic properties or attributes of the speech signal that could be related in some fairly straightforward way to the features and categories used in spoken language. Other studies have employed this procedure to reveal the selectivity of these detector mechanisms for a specific range or subrange of stimuli having a property or attribute in common (Miller, 1975). Such efforts have also been aimed at specifying the level or levels of perceptual analysis that were susceptible to adaptation, under the assumption that such perceptual effects would therefore define the primary channels used by the perceptual system in recognizing phonetic segments and features (Miller, 1977; Sawusch, 1977a, 1977b). Although it has been convenient to describe a number of aspects of the early stages of speech sound perception by appeal to the existence and operation of specialized feature detectors analogous to those found in the visual system, there is currently little consensus among investigators as to the exact nature of these detectors, their structural arrangement, or levels of the perceptual system that are being tapped by the adaptation technique itself. As a consequence, the usefulness of this analogy to the visual system has been called into question as the number of hypothetical detectors and levels of perceptual analysis proliferate with each newly published study (see, e.g., Diehl, Elman, & McCusker, 1978; Elman, 1979; Remez, 1979; Simon & Studdert-Kennedy, 1978). Nevertheless, the adaptation technique has been helpful in detailing some aspects of the perceptual system's selectivity to various properties of the stimulus array. In addition, the immunity of certain stimulus properties from contingent adaptation effects (see Ades, 1976, for a review) offers the interesting suggestion that the perceptual system may not employ the same analytic categories as do linguists and psychologists (see also Remez, 1979).

As additional psychophysical evidence has accumulated over the past few years on the perception of nonspeech signals having properties similar to those found in speech, it has also become increasingly apparent that mechanisms used in speech perception are constrained in numerous ways by the basic capabilities of the auditory system (Divenyi & Sachs, 1978; Miller, Engebretson, Spenner, & Cox, 1977; Searle, Jacobson, & Rayment, 1979). The constraints imposed on acoustic signals by the auditory system have been assumed to delineate some of the basic kinds of acoustic events and properties that languages have exploited in realizing phonetic distinctions (Stevens, 1972). To cite one example of this approach, Pisoni (1977) has suggested recently that the phonetic feature of voicing—a complex set of temporal and spectral events used in distinguishing voiced from voiceless stop consonants—may have its origin in a basic property of the auditory system to respond to differences in the temporal order of events at stimulus onset. When two events occur within 20–25 msec of each other, the auditory system responds differently from the way it does when the relative onsets of two events are greater than 20–25 msec(Hirsh, 1959). Subjects cannot identify the temporal order of two distinct acoustic events when their onsets are separated by less than 20–25 msec—the stimuli are perceived as having simultaneous onsets. However, subjects can identify the temporal order of two events when their onsets differ by more than 20–25 msec (Hirsh, 1959; Hirsh & Sherrick, 1961). In this case, the two events are perceived as occurring successively and ordered in time. It is not unreasonable to suppose that constraints such as these affect the perception of both speech and nonspeech alike.

The present report is a continuation and extension of earlier work on the processing of temporal order information in speech perception and its potential role in signaling voicing differences in stop consonants (see Pisoni, 1977). The results of these experiments with nonspeech signals provided an initial basis for the view that the inventory of phonetic segments used to realize voicing distinctions among stop consonants in a number of languages might reflect a basic limitation on the ability of the auditory system to process temporal order information. For example, in the case of the voicing feature in stop consonants, the time of an occurrence of an event (i.e., the onset of voicing) must be judged in temporal relation to other articulatory events (i.e., the release From stop closure). The fact that these articulatory events occur in precise temporal sequence implies that potentially distinctive and highly discriminable temporal changes will be produced at only certain regions along a temporal continuum, such as the acoustic dimension represented by voice onset time (VOT).

To study the perceptual basis of the voicing feature, Pisoni (1977) generated a set of nonspeech stimuli differing in the relative onsets of two component tones of different frequencies. Earlier experiments with synthetic speech stimuli by Liberman, Delattre, and Cooper (1958) had established the importance of a similar dimension—the Fl “cutback”—as a perceptual cue to voicing in stops, so there was good reason for focusing on this temporal variable in the nonspeech stimuli.

The results obtained in identification and discrimination experiments with these nonspeech stimuli were quite similar to those observed with synthetic speech stimuli differing in VOT (Pisoni, 1977). After familiarity and some minimal training, subjects were able to consistently identify the nonspeech stimuli as belonging to certain well-defined perceptual categories. In addition, discrimination of pairs of these stimuli was very nearly categorical; performance was close to chance for pairs of stimuli selected from within a perceptual category and excellent for pairs of stimuli selected from different perceptual categories. Furthermore, in other experiments it was possible to identify the basis for the underlying perceptual categories in these nonspeech stimuli in terms of whether the acoustic events at stimulus onset were perceived as simultaneous or successive and, if successive, whether the temporal order of the component events could be identified as leading or lagging. These three properties—leading, lagging, and simultaneous—also have been found to characterize the major differences in voicing among stops in a large number of languages as represented by the VOT dimension (Lisker & Abramson, 1964). Thus, it seemed likely that these perceptual results with non-speech stimuli could offer an account of the perceptual findings obtained with synthetic speech stimuli differing in VOT. Similar findings on the discrimination of temporal order information by young infants have been reported recently by Jusczyk, Pisoni, Walley, and Murray (1980).

The temporal order hypothesis of voicing perception in stops proposed in the earlier paper was also able to account for a seemingly diverse set of findings on the perception of VOT reported in the literature. Cross-language differences observed in the perception of VOT by adults as well as a number of perceptual experiments with infants and chinchillas could be rationalized simply by postulating a common underlying basis for the discrimination involving a basic constraint on the auditory systems' ability to resolve differences in temporal order between two events. Earlier studies by Lisker and Abramson (1964, 1967) established the existence of three modes of voicing in stop consonants across some 11 diverse languages. The temporal order hypothesis was formulated to provide a principled psychophysical account of why only three categories of voicing—leading, lagging, and simultaneous—are used in these languages.

Although the results of these initial nonspeech experiments suggested that the perceptual categories underlying voicing distinctions in stops might depend on the extraction of temporal order information, the precise mechanism responsible for detecting differences in the relative timing between two events remained unspecified at the time. If the auditory system responds differently to simultaneous and successive events at stimulus onset, as our previous results indicated, it should be possible to gain some additional, more detailed information about how the auditory system encodes these salient properties by means of perceptual adaptation techniques.

The results of the earliest adaptation experiments on voicing (Eimas & Corbit, 1973) were, in fact, interpreted as support for the operation of detectors in speech perception that were tuned specifically to differences in VOT, the temporal dimension distinguishing voiced and voiceless stops (see also Miller, 1977). However, at that time, it was assumed that the detectors used to process VOT information were specific to processing speech signals, since several control conditions involving the use of nonspeech adaptors failed to produce any systematic cross-series adaptation effects on speech stimuli (Eimas, Cooper, & Corbit, 1973). However, other studies, such as the one reported by Tartter and Eimas (1975) on perception of place of articulation, did show cross-series effects of nonspeech adaptors. Given these earlier findings, it seems equally possible, and perhaps even quite likely, that the auditory system is equipped with property detecting mechanisms of the kind that encode temporal order information in both speech and nonspeech signals. Eimas et al. may simply have failed to identify a more general timing mechanism because of their reliance on speech signals as test stimuli and the specific types of non-speech controls they used.

The first experiment, reported below, was therefore specifically carried out to determine whether the relative onset time between two tones in a set of nonspeech signals would also show perceptual adaptation in a manner analogous to that reported earlier for speech stimuli differing in VOT. Two additional experiments were conducted with these nonspeech stimuli to gain additional information about the selectivity of the perceptual mechanism in processing temporal order information and its susceptibility to adaptation in cross-series tests. Such cross-series tests between speech and nonspeech signals could provide one way of determining whether the same general timing mechanism is used by the perceptual system in processing both speech and nonspeech signals. If such cross-series adaptation effects could be obtained with nonspeech stimuli differing in relative onset time, the results would not only provide additional support for the temporal order hypothesis of voicing perception summarized earlier, but would also establish the existence and operation of a somewhat more general timing mechanism. Such a timing mechanism would respond to temporal onsets in the auditory system regardless of perceptual class, that is, whether the signal is speech or nonspeech. Moreover, this general timing mechanism would, of course, no doubt be very closely tied to what is already known about the basic capabilities of the auditory system to respond to differences in the temporal order of events at stimulus onset.

EXPERIMENT 1

In this experiment, subjects were first trained to identify stimuli selected from a nonspeech auditory continuum by means of a training procedure developed in our earlier studies (Pisoni, 1977). After completing the training and identification testing, subjects who met a strict predetermined criterion were asked to return for two additional sessions in which identification tests were carried out under baseline and adaptation conditions.

Method

Subjects

Twenty-four volunteers served as subjects. They were recruited by means of an advertisement in the student newspaper and were paid at a base rate of $2/h plus whatever they earned during the initial training phase of the experiment. All of the subjects were right-handed native speakers of English who reported no history of a hearing or speech disorder at the time of testing.

Stimuli

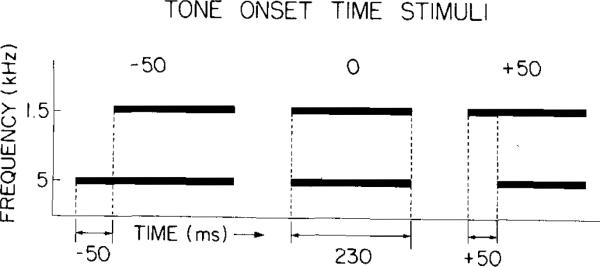

The stimuli consisted of the same 11 two-tone non-speech patterns that were used in the previous experiments reported by Pisoni (1977). These were generated with a computer program that permitted control over the amplitude and frequency of two sinusoids as a function of time. Schematic representations of the time course of these signals are displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of three stimuli differing in relative onset time: leading (−50 msec), simultaneous (0 msec), and lagging (+50 msec).

The frequency of the lower tone was set at 500 Hz, while the frequency of the higher tone was set at 1,500 Hz. The amplitude of the 1,500-Hz tone was adjusted to be 12 dB lower than the 500-Hz tone so as to approximate the amplitude relations observed in natural speech for a neutral vowel. The stimuli differed in terms of the temporal onset of the lower tone relative to the higher tone. As shown in Figure 1, for the −50-msec stimulus, the lower tone leads the higher one by 50 msec; for the 0-msec stimulus, both tones are simultaneous at onset; and for the +50-msec stimulus, the lower tone lags the higher tone by 50 msec. Both component frequencies terminated together at stimulus offset. The duration of the 1,500-Hz tone was always fixed at 230 msec in all of the stimuli, while the duration of the 500-Hz tone was varied to produce the test stimuli. All the remaining intermediate values differing in 10-msec steps from −50 through +50 msec were also generated to form a complete continuum. The 11 test stimuli were generated on a PDP-9 computer at M.I.T., where they were recorded on audiotape, and then later digitized via an A–D converter on a PDP-11 computer in the Speech Perception Laboratory at Indiana University.

Procedure

All experimental events involving the presentation of stimuli, collection of responses from the subjects, and delivery of feedback were controlled on-line by the PDP-11 computer. The digitized waveforms were output via a D–A converter, low-pass filtered, and then presented to the subjects through matched and calibrated Telephonies (TDH-39) headphones. The stimuli were presented at a comfortable listening level of about 80 dB (re: .0002 dynes/cm) throughout the experimental sessions. Testing was carried out in a quiet room equipped with six individual cubicles.

The present experiment consisted of three 1-h testing sessions conducted on separate days. All the subjects were run in small groups that received the same stimulus conditions in a particular testing session. The 1st day was used for training, testing, and the selection of subjects. On the 2nd and 3rd days, the subjects identified these stimuli under both baseline and adapted conditions.

In the initial shaping sessions, the subjects were first presented with the endpoint stimuli, −50 and +50 msec, in a fixed sequence for 160 trials so that the differences between the two stimuli could be discriminated easily. This was followed by a training session in which the same two endpoint stimuli were presented in a random order for 160 trials. The subjects were told to learn which of two response buttons was associated with each sound. Immediate feedback was provided after the presentation of each stimulus indicating the correct response on each trial. No explicit labels or coding instructions were provided, permitting the subjects to adopt their own strategies in learning to categorize these stimuli. After 320 trials, two additional intermediate stimuli (−30 and +30 msec) were included in the training set, and another 160 trials were run. Of the original 24 subjects, 19 met the criterion of at least 90% or better correct performance on the four stimuli in the last block of trials. These subjects were then divided into two groups and asked to return for the remaining sessions on Days 2 and 3.

Testing on Days 2 and 3 was identical for each group and included an initial practice sequence of 80 trials using the endpoint stimuli, −50 and +50 msec, with feedback in effect. This was followed immediately by a baseline identification test in which all 11 stimuli were presented 15 times each in a random order for 165 trials. Finally, identification was measured under adaptation conditions separately for each endpoint stimulus. One group of subjects was assigned the −50-msec stimulus as an adaptor, whereas the other group received the +50-msec stimulus. The subjects received 100 repetitions of the adaptor followed by a single randomized presentation of nine stimuli selected from the middle of the continuum. The subjects were required to identify each of the nine test stimuli as belonging to one of the two response categories they had used earlier in the training and identification sessions, although no feedback was provided. Ten sequences of adaptation and identification testing were run in a session, providing 10 responses for each stimulus per day. Timing and sequencing of trials in the experiment were paced to the slowest subject in a given session.

Results and Discussion

The average identification functions obtained for baseline and adaptation are shown in Figure 2, separately for each of the two adaptation conditions. A small shift can be observed in the identification function measured after adaptation for the −50-msec group, shown in the lefthand panel of the figure. However, examination of the average identification data for the +50-msec group does not reveal a noticeable or consistent difference between the functions obtained for baseline or adaptation, at least when considering the group data as a whole.

Figure 2.

Average nanspeech (TOT) identification functions for baseline and after adaptation in Experiment 1. The −50-msec nonspcech TOT adaptor group is shown on the left; the +50-msec nonspeech TOT adaptor group is shown on the right.

In order to get a better indication of the strength of these results, the locus of the category boundary was determined by an algorithm that interpolated linearly between the two stimulus values on either side of the 50% crossover point in the identification functions. Examination of the individual boundary values given in Table 1 shows that all nine subjects in the −50-msec or “lead” adaptor group showed a shift in their identification functions after adaptation with this endpoint stimulus. The boundary shifts in this condition were small, but, nevertheless, they were in the anticipated direction displaced toward the adapting stimulus. The difference between baseline and adaptation functions for this condition was statistically significant by a one-tailed t test for matched samples (p < .005), indicating the presence of a reliable adaptation effect.

Table 1.

Individual and Mean Category Boundaries (in Milliseconds)

| Subject | B | A | B ‒ A |

|---|---|---|---|

| −50-Msec TOT Adaptor Group | |||

| 7 | 11.7 | 5.3 | +6.4 |

| 8 | 9.3 | 6.6 | +2.7 |

| 9 | 15.2 | 14.6 | + .6 |

| 11 | 15.8 | 14.4 | +1.4 |

| 12 | 7.7 | 4.7 | +3.0 |

| 21 | 7.9 | 6.0 | +1.9 |

| 22 | 18.1 | 15.0 | +3.1 |

| 23 | 18.8 | 15.9 | +2.9 |

| 24 | 20.0 | 12.0 | +8.0 |

| Mean | 13.8 | 10.5 | +3.3 |

| +50-Msec TOT Adaptor Group | |||

| 1 | −14.8 | −13.0 | −1.8 |

| 2 | 15.8 | 15.0 | + .8 |

| 5 | 3.2 | 3.3 | − .1 |

| 6 | 8.3 | 1.0 | +7.3 |

| 13 | 16.8 | 20.0 | −3.2 |

| 14 | −21.2 | −16.6 | −4.6 |

| 15 | 13.6 | 18.3 | −4.7 |

| 16 | 13.7 | 20.0 | −6.3 |

| 17 | 23.4 | 30.0 | −6.6 |

| 18 | 24.4 | 29.0 | −4.6 |

| Mean | 8.3 | 10.7 | −2.4 |

Note–B = baseline; A = adaptation.

Turning to the individual data shown in Table 1 for the subjects in the +50-msec or “lag” group, it can be seen that two of the ten subjects showed boundary shifts after adaptation in the direction opposite to that anticipated. Moreover, one of these subjects showed a large shift in the wrong direction, thus accounting for the relatively small effects shown for the group identification functions when the average data are displayed in Figure 1. However, despite the results for these two subjects, a t test on the differences between baseline and adaptation conditions was significant (p < .05), indicating the presence of a reliable adaptation effect with the +50-msec adaptor as well.

The results of this experiment indicate that small, although reliable, adaptation effects can be obtained with nonspeech stimuli differing in relative onset time of their component frequencies. Although adaptation effects have been observed for other non-speech stimuli, particularly along relatively simple perceptual and sensory dimensions (Ward, 1973), the present results are of special interest because such effects were obtained with a temporal dimension closely related to one studied extensively in speech—VOT. Moreover, these findings encourage the view, already suggested from our earlier work, that the auditory system responds selectively to the temporal order of events and that this temporal dimension may reflect one of the basic patterns of auditory system response in processing of speech as well as other acoustic signals.

EXPERIMENT 2

In this experiment, cross-series tests using synthetic speech stimuli were carried out to determine how selective the earlier adaptation effects were with non-speech adaptors. On one hand, it is possible that the adaptation effects observed for temporal onset are due to a very general timing mechanism that simply responds to differences in temporal onset in the auditory system regardless of whether the signals are speech or nonspeech. On the other hand, the timing mechanism may be quite general, but the specific effects revealed through the adaptation technique could well be more selective, requiring, at the very least, some degree of spectral overlap between the adapting and test stimuli. Finally, it is also possible that two quite distinct processing mechanisms exist in the auditory system for encoding temporal order information, one restricted exclusively to speech and the other to nonspeech signals. The results of the following two cross-series adaptation experiments should help to distinguish these possibilities.

Method

Subjects

Eighteen new volunteers served as subjects. They were recruited in the same way and met all of the requirements as in the previous experiment.

Stimuli

The same 11 nonspeech stimuli differing in temporal onset were also used as test stimuli in this experiment. However, two additional stimuli were used to test for the presence of cross-series adaptation effects from speech to nonspeech. The adaptors were two synthetically produced speech stimuli differing in VOT by −50 msec and +50 msec and were selected from the labial VOT series constructed by Lisker and Abramson (1967). The stimuli consisted of a 450-msec steady-state formant pattern (Fl =769 Hz, F2 = 1,232 Hz, F3=2,525 Hz) appropriate for the vowel /a/, with 45-msec formant transitions at starting values appropriate for a bilabial stop consonant. Voicing lead was simulated by the presence of a low-amplitude first formant at 154 Hz. The aspiration and voicing differences for the voicing lag stop were realized by attenuation of low-frequency energy in Fl and the presence of hiss in the two higher formants. The pitch contour was fixed at 114 Hz for 320 msec and then tapered off linearly to 70 Hz over the remainder of the steady-state portion of the vowel. The entire Lisker and Abramson series was originally recorded on audiotape at Haskins Laboratories and later digitized on the same PDP-11 used in the earlier experiment.

Procedure

The procedure was identical in all ways to that used in the previous experiment except that the −50- and +50-msec VOT stimuli were substituted for the two nonspeech adaptors. The 1st day was used for training, testing, and subject selection. On the 2nd and 3rd days, identifieation tests were carried out under both baseline and adaptation conditions.

Results and Discussion

The average identification functions obtained for both baseline and adaptation are shown in Figure 3, separately for each group of subjects. Examination of the group data displayed in this figure shows no consistent shift in the identification functions for either adaptation condition. When the individual boundary values are examined, as shown in Table 2, it is quite apparent that the speech stimuli differing in VOT simply did not produce any consistent effects on identification of the nonspeech test series.

Figure 3.

Average nonspeech (TOT) identification fonctions for baseline and after adaptation in Experiment 2. The −50-msec VOT speech adaptor group is shown on the left; the +50 msec VOT speech adaptor group is shown on the right.

Table 2.

Individual and Mean Category Boundaries (in Milliseconds)

| Subject | B | A | B ‒ A |

|---|---|---|---|

| −50-Msec VOT Adaptor Group | |||

| 1 | 12.5 | 8.9 | + 3.6 |

| 2 | 20.6 | 17.1 | + 3.5 |

| 3 | 23.4 | 22.9 | + .5 |

| 6 | 15.3 | 16.3 | − 1.0 |

| 20 | 19.2 | 21.0 | − 1.8 |

| 21 | 16.7 | 14.3 | + 2.4 |

| 24 | 17.5 | 16.1 | + 1.4 |

| Mean | 17.9 | 16.7 | + 1.2 |

| +50-Msec VOT Adaptor Group | |||

| 8 | 8.2 | 8.2 | .0 |

| 9 | 5.0 | − 2.0 | + 7.0 |

| 11 | 16.0 | 15.7 | + .3 |

| 12 | 16.4 | 7.1 | + 9.3 |

| 13 | 18.8 | 20.0 | − 1.2 |

| 14 | 24.0 | 18.8 | + 5.2 |

| 15 | 10.0 | 9.1 | + .9 |

| 16 | 24.8 | 20.9 | + 3.9 |

| 17 | −10.7 | −12.0 | + 1.3 |

| 18 | 4.7 | 3.9 | + .8 |

| 19 | 13.9 | 27.3 | −13.4 |

| Mean | 11.9 | 10.6 | + 1.3 |

Note–B = baseline; A = adaptation.

A t test for matched pairs was carried out on the data in each condition to confirm these initial observations, and in both cases, the test failed to reach statistical significance. Thus, the results of the present experiment clearly indicate that speech adaptors differing in VOT are not able to produce cross-series adaptation effects on a set of nonspeech stimuli differing in relative onset time.

Considering the enormous differences in spectral composition between the synthetic speech adaptors and the nonspeech test series used in this experiment, it seems reasonable to conclude that the adaptation effects found for temporal order in the first experiment with nonspeech adaptors were, in fact, quite specific in scope. Such effects were not observed when the adaptors were more complex speech stimuli differing in VOT and the test series consisted of spectrally simpler nonspeech signals. Since the temporal differences in these VOT adaptors were distributed across component formant frequencies containing substantially wider bandwidths than the two-tone components of the nonspeech stimuli, any adaptation that might have been produced may have simply been too broadly spread across the spectrum. Thus, with the sensitivity of the present adaptation technique, it may have been difficult to detect the presence of any of these effects.

In addition to the temporal onset dimension under consideration, a number of other differences can also be noted between the speech and nonspeech adaptors. These factors could have influenced the overall selectivity brought about by repeated stimulation with these speech adaptors. For example, the speech adaptor with the voicing lead (i.e., − 50 msec) contained formant transitions after release, while the speech adaptor with a voicing lag (i.e., +50 msec) contained significant noise during the period of the aspiration interval after release. The extent to which variations in these attributes influence the processing of temporal order information is currently unknown, although potentially important in terms of understanding the initial sensory coding of speech signals by the auditory system.

EXPERIMENT 3

The results of the previous experiment failed to reveal any cross-series adaptation effects on a non-speech continuum when the adapting stimuli were speech signals differing in VOT. Such results could be due to a dissociation of the perceptual mechanisms used to process timing information across different perceptual classes—speech and nonspeech. Alternatively, the outcome might be due simply to an asymmetry from complex to simple signals. In earlier adaptation studies, some evidence was found for adaptation effects on speech stimuli when the adapting stimuli were components of speech signals such as formant transitions or isolated formants (see Samuels & Newport, 1979; Tartter & Eimas, 1975). To determine whether there is a dissociation of processing temporal order information across perceptual classes such as speech and nonspeech, we carried out an additional experiment in which the adaptors were nonspeech TOT stimuli and the test series consisted of speech signals differing in VOT. If cross-series adaptation effects can be found in this experiment, the results would suggest the operation of some fairly general timing mechanism for both speech and nonspeech signals. On the other hand, the absence of cross-series effects from nonspeech to speech, taken together with the results of the previous experiment, would imply a dissociation between perceptual classes and, therefore, a certain degree of selectivity for processing temporal onset information in speech and nonspeech.

Method

Subjects

Nineteen new volunteers were recruited for this experiment. They met the same requirements as in the earlier experiments.

Stimuli

Eleven synthetically produced labial-stop CV syllables, differing in VOT from − 50 to + 50 msec in 10-msec steps, were used as test stimuli. The stimuli were originally produced at Haskins Laboratories by Lisker and Abramson (1967) on the parallel-resonance synthesizer and then recorded on audiotape. The endpoints were identical to the stimuli used in the previous experiment, although all the intermediate VOT values were included in this series as well. The two adapting stimuli were selected from the endpoints of the nonspeech TOT series used in the previous experiments. They had onset time values of − 50 and + 50 msec, respectively.

Procedure

The general procedure was similar to that used in the previous two experiments except that the methods used for training, testing, and subject selection on Day 1 were eliminated, since subjects had no difficulty in identifying the test stimuli as /ba/ or /pa/. As a consequence, all baseline aad adaptation testing could be carried out in one session lasting about an hour. Baseline testing was always conducted first, followed after a short break by adaptation testing. The subjects were required to identify all 11 VOT stimuli during baseline testing but only the middle nine test stimuli during adaptation testing. The stimuli were presented 15 times each for identification under both testing conditions. As in the previous experiments, all timing and sequencing of trials were paced to the slowest subject in a group.

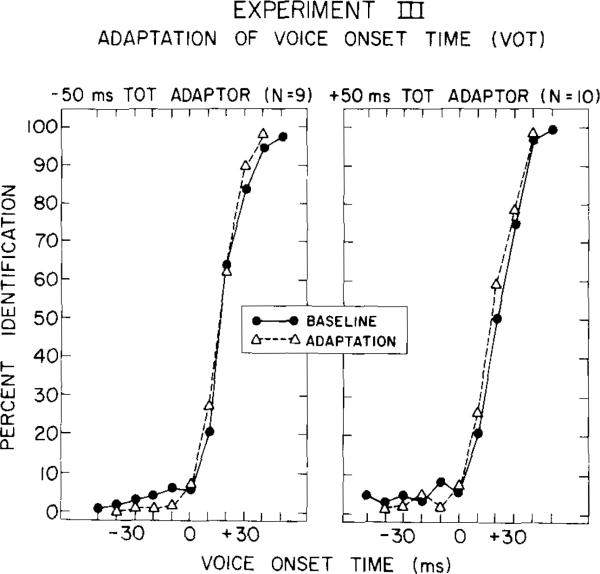

Results and Discussion

The average identification functions obtained during baseline and after adaptation testing are shown in Figure 4, separately for each of the two adaptation conditions. Inspection of the figure reveals no consistent shift in the group identification functions after adaptation in either condition. The individual boundary values of baseline and adaptation are shown in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Average speech (VOT) identification functions for baseline and after adaptation in Experiment 3. The −50-msec nonspcech TOT adaptor group is shown on the left; the +50-msec TOT adaptor group is shown on the right.

Table 3.

Individual and Mean Category Boundaries (in Milliseconds)

| Subject | B | A | B ‒ A |

|---|---|---|---|

| −50-Msec TOT Adaptor Group | |||

| 26 | 30.1 | 24.4 | + 5.7 |

| 27 | 3.6 | 3.0 | + .6 |

| 28 | 16.9 | 23.2 | − 6.3 |

| 29 | 10.8 | 9.0 | + 1.8 |

| 30 | 25.0 | 33.1 | − 8.1 |

| 31 | 17.6 | 14.2 | + 3.4 |

| 38 | 20.6 | 20.6 | .0 |

| 39 | 15.6 | 9.4 | + 6.2 |

| 41 | 16.1 | 11.9 | + 4.2 |

| Mean | 17.4 | 16.5 | − .9 |

| +50-Msec TOT Adaptor Group | |||

| 32 | 17.9 | 5.6 | +12.3 |

| 33 | 34.6 | 34.4 | + .2 |

| 35 | 15.0 | 15.8 | − .8 |

| 36 | 20.6 | 10.7 | + 9.9 |

| 42 | 13.9 | 13.9 | .0 |

| 43 | 10.8 | 21.0 | −10.2 |

| 44 | 26.3 | 25.4 | + .9 |

| 45 | 20.8 | 9.1 | +11.7 |

| 46 | 13.6 | 15.0 | − 1.4 |

| 47 | 34.5 | 34.6 | − .1 |

| Mean | 20.8 | 18.6 | 2.2 |

Note–B = baseline; A = adaptation.

While there is a slight tendency for the boundary values to shift in the expected direction for some subjects after adaptation, the overall differences were not significant as revealed by t tests for matched pairs. As in the previous experiment, cross-series adaptation effects appear to be difficult to obtain, at least under the conditions used in the present experiments. Thus, at least for processing temporal order information, there appears to be a clear dissociation between perceptual classes, since the absence of adaptation effects in both cross-series tests was symmetrical from speech to nonspeech and vice versa. The selective adaptation effects observed for VOT in speech or TOT in nonspeech signals seem to be restricted to a particular perceptual class. Taken at face value, such results would, of course, undermine any arguments in favor of revealing the operation of a very broadly tuned timing mechanism in the auditory system that was sensitive to temporal order information in both speech and nonspeech signals. Thus, when considered in this light, it is apparent that the temporal order hypothesis proposed earlier by Pisoni (1977) is not sufficient by itself to account for the complexity of the numerous temporal and spectral cues to the voicing feature in speech, an issue we will return to in the next section.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The overall results of the present experiments are consistent with earlier findings on perceptual adaptation for speech and nonspeech signals. Several studies have examined the effects of nonspeech adaptors on the perception of speech stimuli in order to gain additional information about the level of processing tapped by the adaptation technique. In general, these cross-series adaptation effects with nonspeech stimuli were smaller in magnitude than the cross-series or within-series adaptation effects obtained with speech stimuli and were closely related, in several cases, to the degree of spectral overlap of the adaptor and test series (see Cooper, 1975; Eimas & Miller, 1978; Sawusch, 1977a).

However, the experiments reported in the present paper differ from these earlier adaptation experiments in several respects. First, the acoustic dimension under consideration here was a temporal variable closely related to one found to distinguish the voicing feature in stop consonants. Previous nonspeech adaptation experiments have been concerned primarily with spectral differences (i.e., Tartter & Eimas, 1975). Second, the subjects could not readily categorize these nonspeech stimuli as they were able to do without training in the earlier “pluck” and “bow” experiments of Cutting et al. (1976). Consequently, some experience and training were required to be able to identify these stimuli consistently. Thus, it is difficult to argue that the subjects had prior conscious experience or familiarity with these particular perceptual dimensions or categories before the experiment began. Finally, the present experiments represent one of the very few attempts reported in the literature to determine the effects of a relatively complex adapting stimulus such as speech on a test series consisting of nonspeech signals differing in temporal order. Other studies have examined the effects of speech on speech and nonspeech on speech (see Diehl, 1976; Remez, Cutting, & Studdert-Kennedy, 1980; Samuel & Newport, 1979), but only one other study has attempted to assess the effects of speech adaptors on a nonspeech test series (Verbrugge & Liberman, 1975). In one condition of this study, listeners were asked to categorize a full series of isolated third formants from an /r/ to /l/ test series. In contrast with the results obtained in the present study, the nonspeech identification boundaries for the isolated /r/ to /l/ stimulus continuum were unstable, and, moreover, no consistent shifts could be induced by either speech or nonspeech adapting stimuli.

The present series of experiments has been carried out in the tradition of earlier selective adaptation experiments in speech perception that were aimed at establishing the existence and operating characteristics of feature detectors. However, over the last few years, a number of papers have raised serious questions about the conclusions and implications of this earlier body of work (see Eimas & Miller, 1978, for a recent review). For example, in a recent paper, Remez (1979) has raised several objections to the opponent-process conceptualization that has been explicitly assumed as the underlying organizational structure of these detector systems. Remez found adaptation effects for a continuum differing between vowel (speech) and buzz (nonspeech) and argued that the presence of such effects implied the existence of a set of detectors organized as opponent pairs for a speech-nonspeech distinction. Remez argued that such a feature opposition is hard to rationalize either linguistically, in terms of what is currently known about the inventory of distinctive features in spoken languages, or psychophysically, with regard to the structure and function of the auditory system. As a consequence, he concluded that selective adaptation of speech does not depend on, or imply, the existence of feature detectors at all, but may result simply from perceptual sensitivity to higher order values inherent in the stimulus pattern.

In another recent paper, Simon and Studdert-Kennedy (1978) have argued that the physiological metaphor of feature detectors in speech perception implied by the selective adaptation experiments is unwarranted in the absence of converging evidence supporting their existence and operation; almost all of the empirical data used to support feature detector models of speech perception have, in fact, come from selective adaptation experiments. Instead, these authors prefer to use a more descriptive or neutral term, “channels of analysis,” to characterize the way the auditory system responds selectively to properties of the stimulus input, whether the signal is speech or nonspeech (see also Eimas & Miller, 1978). Such an account emphasizes the functional rather than structural nature of the observed selective adaptation effects. Hypotheses concerning the underlying structural organization of the mechanisms responsible for the effects can therefore be distinguished from descriptions of the phenomenon itself and the experimental variables that influence its magnitude.

Although the results of our first experiment demonstrated adaptation effects for temporal onset in nonspeech signals, the absence of any cross-series effects in the remaining two experiments is somewhat problematical with regard to the earlier temporal order hypothesis of voicing perception (Pisoni, 1977). First, the within-series adaptation effects were generally quite small in magnitude to begin with, leaving open the possibility that the absence of any adaptation effects in Experiments 2 and 3 might be due to the insensitivity of the current experimental procedures to relatively small effects. Second, it is clear from earlier work by Lisker (1975, 1978) and Summerfield and Haggard (1977) that voicing perception is not based exclusively on the extraction of only a single invariant dimension or property from the speech waveform, such as temporal onset. Rather, the perception of voicing appears to involve a complex integration of a number of somewhat disparate temporal and spectral cues that are highly context sensitive. Finally, there is the more general question raised earlier of precisely what aspects of the perceptual process are being uncovered by the selective adaptation technique. The numerous studies carried out over the last few years all seem to support the conclusion that the perceptual dimensions revealed through selective adaptation are quite selective in their susceptibility to fatigue and are not as general as investigators may have originally thought a few years ago (Eimas & Corbit, 1973). Based on the present findings, we are led to conclude that selective adaptation may simply not reveal the operation of a broadly tuned timing mechanism that processes temporal order information in the auditory system. Such a mechanism, if it exists at all, appears to be selective across classes of signals such as speech or nonspeech.

Even if the processing of temporal order information in speech and nonspeech is not mediated through the same perceptual mechanisms as the present results seem to suggest, the perception of both classes of signals is similar in some sense, because they are constrained by the fundamental limits of processing temporal order information in the auditory system. Such a view implies that the structure and function of the auditory system control the early processing of speech and nonspeech signals alike. Search for commonalities between the two perceptual classes is therefore an important goal in future research on speech perception, although psychophysical and sensory-based accounts have often been over-looked in favor of more abstract accounts that deal only with the perception of speech signals. While there are, no doubt, important differences in perception between speech and nonspeech signals, there may also be many similarities based on common psychophysical and perceptual processes. A detailed account of such similarities might help to establish a well-defined underlying perceptual basis for the acoustic correlates of the relatively small number of distinctive features found in spoken language.

Taken together with the results of our earlier non-speech experiments, the present findings may therefore be thought of as examples of how the auditory system constrains the range of potential acoustic attributes that can be employed to signal phonetic distinctions in language. The inventory of distinctive acoustic attributes in speech appears to be limited both by the sound-generating properties of the vocal tract and the sensory capabilities of the auditory system.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by NIMH Research Grant MH-24027 and NINCDS Research Grant NS-12179. The final version of the manuscript was completed while the author held a Guggenheim fellowship during a sabbatical leave at the Speech Group, Research Laboratory of Electronics, M.I.T. I thank Jerry C. Forshee at Indiana University for his continued technical assistance and advice. Robert E. Remez and Michael Studdert-Kennedy offered critical and very helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper, and their efforts are greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- Ades AE. Adapting the property detectors for speech perception. In: Wales RJ, Walker ECT, editors. New approaches to language mechanisms. North-Holland; Amsterdam: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper WE. Selective adaptation to speech. In: Restle F, Shiffrin RM, Castellan NJ, Pisoni DB, editors. Cognitive theory. Vol. 1. Erlbaum; Potomac, Md: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cutting JE, Rosner BS, Foard CF. Perceptual categories for musiclike sounds: Implications for theories of speech perception. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1976;28:361–378. doi: 10.1080/14640747608400563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl RL. Feature analyzers for the phonetic dimension stop vs. continuant. Perception & Psychophysics. 1976;19:267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl RL, Elman JL, McCusker SB. Contrast effects on stop consonant identification. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1978;4:599–609. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.4.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divenyi PL, Sachs RM. Discrimination of time intervals bounded by tone bursts. Perception & Psychophysics. 1978;24:429–436. doi: 10.3758/bf03199740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimas PD, Cooper WE, Corbit JD. Some properties of linguistic feature detectors. Perception & Psychophysics. 1973;13:247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Eimas PD, Corbit JD. Selective adaptation of linguistic feature detectors. Cognitive Psychology. 1973;4:99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Eimas PD, Miller JL. Effects of selective adaptation on the perception of speech and visual patterns: Evidence for feature detectors. In: Walk RD, Pick HL, editors. Perception and experience. Plenum; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Elman JL. Perceptual origins of the phoneme boundary effect and selective adaptation to speech: A signal detection theory analysis. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1979;665:190–207. doi: 10.1121/1.382235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh IJ. Auditory perception of temporal order. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1959;31:759–767. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh IJ, Sherrick CE. Perceived order in different sense modalities. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1961;62:423–432. doi: 10.1037/h0045283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk P, Pisoni DB, Walley A, Murray J. Discrimination of relative onset time of two-component tones by infants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1980;67:262–270. doi: 10.1121/1.383735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman AM, Delattre PC, Cooper FS. Some cues for the distinction between voiced and voiceless stops in initial position. Language and Speech. 1958;1:153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lisker L. Is it VOT or a first-formant transition detector? Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1975;57:1547–1551. doi: 10.1121/1.380602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisker L. In qualified defense of VOT. Language and Speech. 1978;21:375–383. doi: 10.1177/002383097802100413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisker L, Abramson AS. A cross language study of voicing in initial stops: Acoustical measurements. Word. 1964;20:384–422. [Google Scholar]

- Lisker L, Abramson AS. The voicing dimension: Some experiments in comparative phonetics. Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences; Prague: Academia; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JD, Engebretson AM, Spenner BF, Cox JR. Preliminary analyses of speech sounds with a digital model of the ear. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62:S1–S13. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JL. Properties of feature detectors for speech: Evidence from the effects of selective adaptation on dichotic listening. Perception & Psychophysics. 1975;18:389–397. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JL. Properties of feature detectors for VOT: The voiceless channel of analysis. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62:641–648. doi: 10.1121/1.381577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisoni DB. Identification and discrimination of the relative onset of two component tones: Implications for voicing perception in stops. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;61:1352–1361. doi: 10.1121/1.381409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE. Adaptation of the category boundary between speech and nonspeech: A case against feature detectors. Cognitive Psychology. 1979;11:38–57. doi: 10.1016/0010-0285(79)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remez RE, Cutting JE, Studdert-Kennedy M. Cross-series adaptation using song and string. Perception & Psychophysics. 1980;27:524–530. doi: 10.3758/bf03198680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel AG, Newport EL. Adaptation of speech by nonspeech: Evidence of complex acoustic cue detectors. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1979;5:563–578. doi: 10.1037/h0078136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawusch JR. Peripheral and central processes in selective adaptation of place of articulation in stop consonants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62:738–750. doi: 10.1121/1.381545. a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawusch JR. Processing place information in stop consonants. Peeception & Psychophysics. 1977;22:417–426. b. [Google Scholar]

- Searle CL, Jacobson JZ, Rayment SG. Stop consonant discrimination based on human audition. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1979;65:799–809. doi: 10.1121/1.382501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon HJ, Studdert-Kennedy M. Selective anchoring and adaptation of phonetic and nonphonetic continua. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1978;64:1338–1357. doi: 10.1121/1.382101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens KN. The quantal nature of speech: Evidence from articulatory-acoustic data. In: David EE Jr., Denes PB, editors. Human communication: A unified view. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield AQ, Haggard MP. On the dissociation of spectral and temporal cues to the voicing distinction in initial stop consonants. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1977;62:435–448. doi: 10.1121/1.381544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartter VC, Eimas PD. The role of auditory and phonetic feature detectors in the perception of speech. Perception & Psychophysics. 1975;18:293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge RR, Liberman AM. Context-conditioned adaptation of liquids and their third formant components. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1975;57:52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ward WD. Adaptation and fatigue. In: Jerger J, editor. Modern developments in audiology. Academic Press; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]