Abstract

Although children born preterm or low birth weight (PT LBW) are more likely to exhibit behavior problems compared to children born at term, developmental and family processes associated with these problems are unclear. We examined trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms in relation to toddler compliance and behavior problems in families with PT LBW infants. A total of 177 infants (93 boys, 84 girls) and their mothers enrolled in the study during the infant’s NICU stay. Data were collected at five time points across 2 years. Assessments of maternal depressive symptoms were conducted at all time points, and toddler compliance and opposition to maternal requests and behavior problems were assessed at 2 years. Toddlers born earlier with more health problems to mothers whose depressive symptoms increased over time exhibited the most opposition to maternal requests during a cleanup task at 24 months, consistent with multiple risk models. Mothers with elevated depression symptoms reported more behavior problems in their toddlers. The study has implications for family-based early intervention programs seeking to identify PT LBW infants at highest risk for problem behaviors.

Each year in the United States, approximately 13% of infants are born prior to term (≤36 weeks’ gestation), and 8% are born low birth weight (<2,500 g) (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2007). Although high-risk infants have a better chance of surviving now than ever before, children born preterm or low birth weight (PT LBW) experience elevated risk for developing cognitive delays and behavior problems compared to children born full-term, especially when infants are very preterm, very low birth weight (VLBW), or experience more medical complications (e.g., Bhutta, Cleves, Casey, Cradock, & Anand, 2002; Clark, Woodward, Horwood, & Moor, 2008; Miceli et al., 2002). In addition, mothers of infants born PT LBW are at risk for experiencing psychological distress and symptoms of depression (e.g., Klebanov, Brooks-Gunn, & McCormick, 2001), particularly in the months following the child’s birth. Although these symptoms often subside over time (e.g., Miles, Holditch-Davis, Schwartz, & Scher, 2007; Poehlmann, Schwichtenberg, Bolt, & Dilworth-Bart, 2009), it is important to examine the implications of maternal depression trajectories for the development of infants born PT LBW because research with full-term infants consistently has documented links between persistent maternal depression and less optimal child outcomes [e.g., Campbell, Morgan-Lopez, Cox, & McLoyd, with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Early Child Care Research Network, 2009; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 1999].

The present study sought to extend this literature to infants born PT LBW who did not experience significant neurological findings during their NICU stay. Thus, the goal of the study was to examine toddler compliance, opposition, and behavior problems in relation to maternal depressive-symptom trajectories over time in a sample of children born PT LBW.

Transactional developmental theory (Sameroff & Fiese, 2000) and other developmental risk models (e.g., Rutter, 1987) posit that multiple environmental risk factors exert their influence on children’s development over time, increasing the likelihood of problematic outcomes. Examples of potent child-, parent-, and family-level risks include infant prematurity, maternal mental health problems, and family sociodemographic risks associated with poverty. Ecological theories recognize that children’s proximal environments are multidimensional (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994) and that children may exhibit differences in susceptibility to both positive and negative family environments (Belsky, 1997, 2005; Bronfenbrenner, 1989).

In the present study, we conceptualized prematurity and its accompanying medical complications as an infant factor that may heighten the potentially negative effects of maternal depressive symptoms on children’s behavior problems, although we did not examine effects of positive parenting in this paper. For medically fragile infants, emotional and behavioral dysregulation may occur if the parenting environment does not adequately support their development, such as when maternal depressive symptoms remain high or increase following a nonnormative or stressful birth experience. Transactional models suggest that children and parents have bidirectional influences on one another (Sameroff & Fiese, 2000). In a previous report, we examined infant, maternal, and family risks as predictors of maternal depression trajectories over time following the birth of a PT LBW infant (Poehlmann et al., 2009). In this report, we explored the potential implications of such trajectories for emerging behavioral development of affected children, including compliance with and opposition to maternal requests.

EMERGING COMPLIANCE AND OPPOSITIONAL BEHAVIORS

A child’s compliance with parental requests has been conceptualized as a very early form of self-control that occurs within the context of the parent-child relationship (Kopp, 1982). Kochanska and colleagues (Kochanska, 2002; Kochanska & Aksan, 1995; Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001) proposed two motivationally different forms of compliance. Committed compliance occurs when the child fully and eagerly complies with a parent’s request, leading to internalization of parental rules and standards and more optimal development. Situational compliance occurs when the child’s cooperation requires sustained parental control (and thus is not considered true compliance). In contrast, noncompliance, opposition to parental requests, and defiance are forms of dysregulation that may occur when children do not comply. Sometimes, negative affect and behaviors may escalate, which may be associated with subsequent externalizing behavior problems. In the present study, we examine toddler committed compliance and opposition to maternal requests in relation to maternal depressive symptoms in toddlers born PT LBW. Although a growing body of research has examined developmental antecedents and consequences of compliance and opposition in healthy, full-term infants, studies have not extended this research to PT LBW infants.

MATERNAL DEPRESSION

The birth of a preterm infant is a nonnormative event that often leads to significant parental stress as the result of infant medical complications, concerns about infant survival, and separation from the infant caused by lengthy NICU stays (Davis, Edwards, Mohay, & Wollin, 2003). These stressors can contribute to psychological distress and depression, especially in mothers (Logsdon, Davis, Birkimer, & Wilkerson, 1997). Research has documented postnatal elevations in maternal distress in mothers of high-risk, preterm infants compared to mothers of healthy, full-term infants (e.g., O’Brien, Asay & McCluskey-Fawcett, 1999), although symptoms tend to decline over time (Miles et al., 2007; Poehlmann et al., 2009).

Elevated maternal depressive symptoms have implications for children’s development, and the development of PT LBW infants in particular. For example, Singer et al. (1999) found that severity of maternal depression related to less optimal cognitive outcomes at 8, 12, 24, and 36 months for VLBW preterms, but not for fullterm infants. Poehlmann and Fiese (2001) found that elevated, but subclinical, maternal depressive symptoms significantly predicted insecure attachment in preterm, but not in full-term, infants. Recently, Bugental, Beaulieu, and Schwartz (2008) found that cortisol levels in preterm infants were more affected by maternal depression compared to full-term infants. However, stable elevations in maternal depressive symptoms have been associated with problematic outcomes in children and adolescents born healthy and full-term as well (Campbell et al., 2009). A meta-analysis of 33 studies has explored the magnitude of the association between maternal depression and behavior problems in children 1 year of age and older and revealed a moderate association between maternal depressive symptoms and child externalizing behavior problems (Beck, 1999).

Preterm infant outcomes also may be influenced by the chronicity of maternal depressive symptoms, with children who interact with more chronically depressed mothers being at greatest risk (Cornish et al., 2005; Trapolini, McMahon, & Ungerer, 2007). Because mothers of preterm infants are likely to exhibit high levels of distress and depressive symptoms following the child’s birth, it is important to examine how the subsequent symptom trajectory predicts child outcomes. In addition, the relation between maternal symptom trajectories and children’s outcomes may be amplified (i.e., moderated) by infant vulnerabilities such as lower birth weight, younger gestational age, and medical complications, consistent with multiple risk models. Lower birth weight and sicker infants may require a higher level of sensitive responsiveness from their mothers to achieve regulatory milestones within the family social context compared to healthier infants, and increasing maternal depressive symptoms may interfere with this process.

STUDY HYPOTHESES

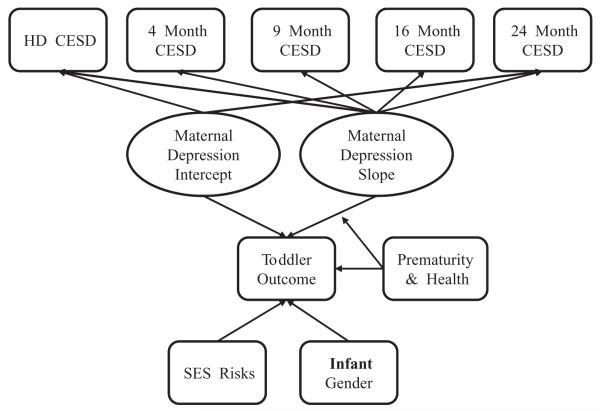

We hypothesized that PT LBW children of mothers whose depressive symptoms increased over time would exhibit less compliance, more opposition, and more behavior problems compared to children of mothers whose depressive symptoms decreased. In addition, we speculated that the association between maternal depression trajectories and toddler outcomes would be moderated by degree of infant prematurity and neonatal health risks. Specifically, we hypothesized that infants born more premature with more health risks to mothers whose depressive symptoms increased over time would exhibit the most opposition, least compliance, and most behavior problems at 24 months’ postterm compared to infants born closer to term and with fewer health risks (see Figure 1). Associations between initial and concurrent maternal depressive symptoms and toddler outcomes also were assessed. We hypothesized that concurrent maternal depressive symptoms would be associated with less toddler compliance, more opposition, and elevated behavior problems. We predicted similar associations between initial maternal depression symptoms (at hospital discharge) and toddler outcomes, although we expected the magnitude of these associations to be smaller given the length of time between maternal depression and toddler outcome assessments (~24 months).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model linking maternal depressive symptoms with toddler outcomes in infants born preterm or low birth weight. HD = hospital discharge; CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; SES = socioeconomic status.

Because the consequences of poverty penetrate most developmental domains (Dearing & Taylor, 2007) and because studies have found more compliance among girls compared to boys (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000), we included family sociodemographic risks and infant gender as controls in our models.

METHOD

Participants

A total of 181 mothers and their infants were recruited from three 35 weeks’ gestation or weighed <2,500 g at birth; (b) infants had no known congenital malformations, prenatal drug exposures, or significant neurological findings during the NICU stay (e.g., Down syndrome, periventricular leukomalacia, grade IV intraventricular hemorrhage); (c) mothers were at least 17 years of age; (d) mothers could read English; and (e) mothers self-identified as the child’s primary caregiver. Because the hospitals would not allow us to be the “first contact” for families and they gave us only information about families who signed consent forms for the study, we were unable to calculate a participation rate; however, of the 186 mothers who signed consent forms, 181 (97%) participated in data collection, and data from 177 families were utilized in this report. Data from 4 of the original 181 families were removed because we later discovered from our review of infant medical records that a grade IV intraventricular hemorrhage had occurred prior to the infants’ NICU discharge and/or the children were later diagnosed with cerebral palsy. If a child was part of a multiple birth, one child was randomly selected to participate in the study (Thirty-four children were multiples.)

Participating family characteristics paralleled the population of Wisconsin during the years of data collection. For example, 77% of mothers who gave birth in 2005 in Wisconsin were White, 9% were Black, and 9% were Latina (Martin et al., 2007), although the rate of preterm birth is higher for Black (18%) than it is for White (12%) infants (Hamilton et al., 2007). Our sample consisted of 66% White, 14% Black, 2% Latino, and 17% multiracial infants. In Wisconsin, 89% of mothers who gave birth were between 20 and 39 years of age, and an average of 15.5% of children lived in poverty in Wisconsin between 2003 and 2005 (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2003-2005). Approximately 86% of the mothers in our sample were between 20 and 39 years of age, and 38 (22%) were living in poverty (see Table 1 for a description of our sample at the time of hospital discharge). Please note that the participating NICUs do not routinely collect demographic information from families served, so we were unable to compare sample demographic characteristics with those of the NICU populations.

TABLE 1. Sample Demographic and Neonatal Characteristics at NICU Discharge.

| Variables | Range or Frequency (%) | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age | 17–42 | 29.60 | 6.27 |

| Maternal Education (years) | 8–21 | 14.28 | 2.68 |

| Family Income per Year | $0–500,000 | $60,035 | $53,470 |

| Gender of Child | |||

| Male | 93 (52.5%) | ||

| Female | 84 (47.5%) | ||

| Infant Race | |||

| African American | 24 (13.5%) | ||

| Asian | 1 (0.6%) | ||

| Caucasian | 117 (66.1%) | ||

| Latino | 3 (1.7%) | ||

| Middle Eastern | 2 (1.1%) | ||

| Multiracial | 30 (17.0%) | ||

| Infant Gestational Age (in weeks) | 23–37 | 31.43 | 3.08 |

| Infant Birth Weight | |||

| Extremely Low (<1,000 g) | 28 (15.8%) | ||

| Very Low (<1,500 g) | 38 (21.5%) | ||

| Low (<2,500 g) | 98 (55.4%) | ||

| Normal (≥2,500 g) | 13 (7.3%) | ||

| Days Hospitalized | 2–136 | 332.92 | 27.81 |

| Multiple Birth | 34 (19.2%) | ||

| Medical Concerns | |||

| apnea | 109 (67%) | ||

| RDS | 86 (53%) | ||

| CLD | 17 (10%) | ||

| reflux | 15 (9%) | ||

| ROP | 2 (1%) | ||

| Sepsis and Other Infections | 19 (12%) |

RDS = respiratory distress syndrome; CLD = chronic lung disease; reflux = gastroesophageal reflux; ROP = retinopathy of prematurity.

Infants and their families were assessed at five time points: just prior to the infant’s hospital discharge (Time 1) and again at 4 (Time 2), 9 (Time 3), 16 (Time 4), and 24 (Time 5) months, corrected for prematurity. Corrected age was calculated on the basis of the infant’s due date and is commonly used for assessments of preterm infants’ development (DiPietro & Allen, 1991).

There was a 14% attrition rate between NICU discharge and 24 months. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to examine potential differences between families who continued in the study for 2 years and families lost to attrition. The first MANOVA was conducted on infant health variables and revealed no significant differences, F(6, 172) = 1.36, p .24, for infant gestational age, birth weight, 1- and 5-min Apgar=scores, days hospitalized, or the neonatal health risk index. The second MANOVA, conducted on Time 1 (NICU discharge) family sociodemographic variables, approached trend-level significance, F(7, 167) = 1.90, p < .08. Follow-up univariate tests indicated that mothers lost to attrition were younger, F(1, 173) = 5.51, p < .05, had completed fewer years of education, F(1, 173) = 5.88, p < .05, and had slightly higher sociodemographic risk index scores, F(1, 173) = 3.23, p < .08, compared to mothers who continued in the study. However, the attrition groups did not differ on number of children in the family, paternal age or education, or family income. Chisquare analyses revealed that mothers lost to attrition also were more likely to be single, χ2 (1) = 4.68, p < .05, and non-White, χ2 (1) = 5.57, p < .05, compared to mothers who remained in the study. However, a one-way ANOVA revealed that Time 1 depressive symptoms did not differ between mothers who continued in the study and mothers lost to attrition, F(1, 177) = 0.35, p = .56. Our attrition is consistent with other longitudinal studies of high-risk infants (Miles et al., 2007).

Measures

Infant prematurity and neonatal health

Infant medical records were reviewed to collect infant prematurity and neonatal health data to create a neonatal health risk index, drawing on previous indices used for PT LBW infants (e.g., Littman & Parmalee, 1978; Scott, Bauer, Kraemer, & Tyson, 1997). Because infant birth weight and gestational age were highly correlated, r(181) = .88, p < .01, we standardized and summed them. We then reverse-scored the composite so that higher scores reflected more prematurity and lower birth weight (so we could combine it with neonatal medical complications).

Next, the following 10 dichotomized neonatal medical complications (1 = present, 0 = absent) were summed and standardized (The proportion of infants experiencing each of these risks is indicated in parentheses): apnea (68%), respiratory distress (53%), chronic lung disease (10%), gastroesophageal reflux (9%), multiple birth (19%), supplementary oxygen at NICU discharge (10%), apnea monitor at NICU discharge (44%), 5-min Apgar score <6 (3%), ventilation during NICU stay (mechanical or continuous positive airway pressure) (53%), and NICU stay of >30 days (39%). We then summed this standardized risk index with the reversed-scored prematurity composite. The resulting index (M = −.05, SD = 2.68) had a Cronbach’s α of .70, with higher scores reflecting poorer neonatal health and more prematurity.

Maternal depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977; CES-D) was used to assess maternal depressive symptoms at each time point. The CES-D is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that asks respondents to rate their symptoms of depression on a scale of 0 (rarely/none of the time) to 4 (most/all of the time) during the past week. Scores ≥16 are considered in the clinical range. Alphas for the present study across time points ranged from .85 to .89 (M = .88). At NICU discharge, 32% of mothers reported clinically significant symptoms, and this decreased to 19% at 4 months, 17% at 9 months, 11% at 16 months, and 12% at 24 months’ postterm. At NICU discharge, an additional 36% of mothers reported elevated, but subclinical, symptoms (scores between 8-15, following Campbell et al., 2009).

Toddler compliance and opposition

The child’s compliance with and opposition to maternal requests were assessed through a toy cleanup task that followed an unstructured 15-min play session. During the play session, children and their mothers were given the opportunity to play with a range of age-appropriate toys. At the end of the play session, children were given a large plastic bin, and mothers were instructed to have the child pick up the toys. The cleanup session ended when the toys were picked up or after 10 min, whichever came first. The cleanup session was videotaped and coded. We used a continuous approach to coding, using 30-s intervals based on Kochanska and Aksan (1995). The following mutually exclusive codes were used: (1) committed compliance (CC), which indicated that the child followed the mother’s request without reminders or coercion while exhibiting positive affect; (2) situational compliance, which indicated that although the child generally followed the mother’s request, he or she did so without positive affect, enthusiasm, or a sense of cooperation; (3) passive noncompliance, which indicated that although the child did not pick up the toys, he or she did not become involved in overt conflict with the mother; (4) refusal negotiation, which indicated that the child did not pick up the toys, the mother attempted to coerce the child, and the child negotiated and/or refused; and (5) defiance, which indicated that the child did not pick up the toys and that angry interactions ensued.

Videotapes were coded by four trained students. Exact percent agreement across 10 independently coded tapes (from this study) ranged from .76 to .79, and agreement within 1 point ranged from .94 to .98. Kappas ranged from .60 to .77, with a mean of .68. Following Kochanska (2002), we used these codes to calculate the proportion of time children spent in committed compliance (proportion of committed compliance intervals) and opposition (proportion of passive noncompliance, refusal negotiation, and defiance intervals combined). Across the intervals coded, 43% of children had one or more intervals in which they exhibited committed compliance (M = 0.39, SD = 0.43) whereas 93% of children had one or more intervals in which they exhibited some form of opposition to maternal requests, typically passive noncompliance, or refusal negotiation (M = 0.52, SD = 0.29). We did not use the situational compliance code in this study (Variability was low likely because situational compliance is so common among 2-year-olds.)

Toddler behavior problems

The problem list of the preschool form of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) was used to assess children’s behaviors at 24 months’ post-term. The CBCL is a widely used, standardized behavior-rating scale that is completed by an adult with whom the child lives. The preschool form lists 99 problem behaviors. Mothers rated each problem behavior on a scale 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 (very true or often true) in reference to the child’s behaviors that occurred during the past 2 months. Responses were then summed to obtain scores for Internalizing and Externalizing Problems scales that were converted into T-scores on the basis of normative data (although raw scores were used in analyses) (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000).

The CBCL is a reliable and valid measure of children’s problem behaviors that was normed for children in this age group, and it has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s αs = .78-.97). In addition, the CBCL has been used with children born PT LBW (e.g., Yu, Buka, McCormick, Fitzmaurice, & Indurkhya, 2006). In the present study, the Internalizing scale (raw score M = 8.42, SD = 6.17) had an alpha of .85, and the Externalizing scale (raw score M = 14.58, SD = 8.12) had an alpha of .91.

Family sociodemographic risks

Mothers completed a demographic questionnaire during the infant’s NICU stay. Based on research that uses a multiple risk model (Sameroff, Bartko, Baldwin, Baldwin, & Seifer, 1998; Sameroff, Seifer, Baldwin, & Baldwin, 1993), 1 point was given for each of the following risks: The family’s income was below federal poverty guidelines adjusted for family size, both parents were unemployed, the mother was single, the mother gave birth to the child as a teen, the family had four or more dependent children, the mother had less than a high-school education, and the father had less than a high-school education. The index could range from 0 to 7, with higher scores reflecting more risks. Cronbach’s α was .75. In the present study, the index ranged from 0 to 6 (M = 1.03, SD = 1.53). We assessed these variables at all time points, and risk scores were highly correlated; we used NICU discharge demographic data for the sociodemographic risk index to minimize missing data.

Procedure

Families were enrolled in the study through three hospitals in Southeastern Wisconsin following institutional review board approval from the University of Wisconsin and each hospital. A research nurse from each hospital described the study to eligible families, and interested mothers signed informed consent forms. A researcher met the mother in the NICU just prior to the infant’s discharge to collect Time 1 data, and mothers completed self-administered questionnaires, including a demographic form and the CES-D at that time. Nurses completed a History of Hospitalization form by reviewing the infant’s medical records shortly after NICU discharge. Home visits were conducted with families when infants were 4 and 9 months’ corrected age. At these visits, researchers asked mothers to complete self-administered questionnaires in addition to videotaping mother-child interactions. Each of the home visits lasted approximately 1.5 hr. Mothers were paid $25 for the 4-month visit and $40 for the 9-month visit. When infants were 16 and 24 months’ postterm, families visited our laboratory playroom. Mothers and children were videotaped playing together, and mothers completed self-administered questionnaires while a researcher administered a standardized developmental assessment to the child. At the 24-month visit, children also participated in a parent-led toy cleanup task with their mothers. Each of the laboratory visits lasted approximately 1.5 to 2 hr. Mothers were paid $65 at 16 months and $80 at 24 months.

PLAN OF ANALYSIS

The conceptual model (Figure 1) was assessed via structural equation modeling (SEM) with Mplus Version 5. Two growth curve models were estimated for each toddler outcome. In the first model, hospital discharge (HD) CES-D scores were set as the intercept, and infant gender and family sociodemographic risk served as controls. The second model contained the same controls, but set 24-month CES-D scores as the intercept. Each model assessed maternal-depression trajectories as the average linear slope across all time points, including variability around the average linear slope. For example, a mother whose depressive symptoms started high and gradually decreased over time would have a negative overall slope. Each model was specified, indentified, and tested for assumption violations prior to model and path estimation and interpretation. Within Mplus, a maximum likelihood robust estimation procedure was used to minimize the bias generated by nonnormality among some of the variables. In addition, a full information maximum likelihood procedure was used to address missing data when complete data were provided across at least two time points. In the full information maximum likelihood procedure, individual missing data patterns are assessed, and means and covariances for each missing data pattern are calculated to inform the observed information matrix (Arbuckle, 1996; Kaplan, 2009). The observed information matrix is used to generate estimates (Kenward & Molenberghs, 1998), assuming data are missing at random (Little & Rubin, 1989), and is preferable to pairwise or listwise deletion or imputation methods (Arbuckle, 1996).

To assess the overall model fit, three indices were assessed: chi-square (χ2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI). The χ2 index is a model of misspecification; therefore, a significant χ2 means that the model does not fit the sample data. Because some scholars have claimed that the exact fit tested in χ2 is an unrealistic standard, indices of approximate fit such as RMSEA also were assessed (Kaplan, 2009). RMSEA tests whether the model approximately fits the population. In RMSEA, .00 is the best possible fit, with higher values indicating poorer fit. Acceptable fit within the RMSEA index is generally .05 (Browne & Cudeck, 1992), although this cutoff has been debated. Within this study, the CFI compares the specified model to a null model. The null model posits no associations among the variables. CFI ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better fit; values above .90 are interpreted as acceptable model fit (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). Table 2 provides χ2, RMSEA, and CFI estimates for each model. Each interpreted model had acceptable fit across at least one of the indices. After model fit was assessed, individual path coefficients were interpreted. Standardized path coefficients (β) are reported, and those that reached the critical ratio of 1.96 were considered significant.

TABLE 2. Model Fit Indices and Standardized Path Estimates for Toddler Committed Compliance, Opposition, and Externalizing and Internalizing Behavior Problems (n = 163).

| Model Fit | Committed Compliance | Opposition | Externalizing Problems | Internalizing Problems | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2(df = 29) | 41.42 | 41.09 | 44.04* | 42.80* | ||||

| CFI | .95 | .96 | .95 | .95 | ||||

| RMSEA | .05 | .05 | .06 | .05 | ||||

| Path Estimates | β | z | β | z | β | z | β | z |

| DI on SES | .41 | 4.53** | .41 | 4.52** | .42 | 4.62** | .42 | 4.57** |

| DS on SES | .65 | 2.10* | .65 | 2.10* | .60 | 2.21* | .61 | 2.18* |

| Outcome on | ||||||||

| DI | .15 | 1.18 | −.11 | −.87 | .53 | 5.70** | .29 | 2.24* |

| DS | −.10 | −.28 | −.02 | −.07 | .40 | 1.21 | .61 | 1.25 |

| PNH | −.15 | −2.12* | .11 | 1.41 | −.13 | −1.82† | −.11 | −1.47 |

| DS × PNH | −.06 | −.95 | .20 | 2.90** | −.03 | −.48 | −.04 | −.73 |

| SES | −.16 | −.73 | .15 | .72 | −.21 | −.85 | −.29 | −.66 |

| Gender | .14 | 1.73† | −.19 | −2.52* | −.04 | −.54 | .13 | 1.76† |

Note.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

CFI = comparative fit index, RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation, β = standardized path estimate, DI = depression intercept (at hospital discharge), DS = depression slope, PNH = prematurity and neonatal health, SES = socioeconomic risks.

RESULTS

Across each of the models tested, the family sociodemographic risk control variable was associated with the maternal depressive symptom intercept and slope (Table 2). Mothers who experienced more socioeconomic status risks reported elevated depressive symptoms (at hospital discharge and when their toddlers were 24 months’ corrected age) and were more likely to experience increasing depression trajectories over time rather than the normative pattern of a decreasing trajectory. For a more detailed presentation of the relation between socioeconomic status risks and maternaldepression trajectories in this sample, see Poehlmann et al. (2009). Additional path estimates are described by toddler outcome.

Toddler Compliance

Toddler committed compliance was predicted by infant health risks, β −.15 (CI.95 = −.28, −.01), SE = .07, z = −2.12, p < .05. Infants who were born earlier and at higher medical risk exhibited less committed compliance with their mothers at 24 months’ corrected age compared to healthier infants. Other variables in the model were not statistically significant predictors.

Toddler Opposition

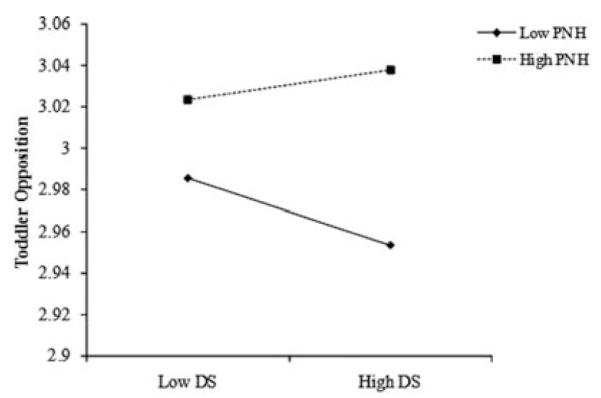

For opposition to maternal requests, the model included two significant predictors: infant gender, β −.19 (CI.95 −.34, −.04), SE = .08, z = −2.52, p < .05 and the interaction term between health risk and maternal depression slope, β .20 (CI.95 = .06, .33), SE = .07, z = 2.90, p < .01. Boys exhibited more oppositional behaviors than did girls. For the interaction term, the path coefficient revealed that toddlers with more health risks born to mothers whose depression increased over time exhibited the highest levels of opposition compared to other children. Figure 2 indicates that when mothers’ depression increased over time (high-slope group), toddlers who experienced more health risks exhibited the most opposition and toddlers born later and healthier exhibited the least opposition whereas the means for opposition in the decreasing (low-slope) group did not differ by infant health.

Figure 2.

Interaction between maternal depression slope (DS) and prematurity-neonatal health risks (PNH) on toddler opposition.

Toddler Externalizing Behavior Problems

Maternal reports of toddler externalizing behavior problems at 24 months’ postterm were predicted by initial maternal depressive symptoms (at NICU discharge), β .53 (CI.95 = .29, .77), SE = .09, z = 5.70, p < .01, and concurrent (24-month) depressive symptoms, β .74 (CI.95 = .45, .96), SE = .11, z = 6.60, p < .01. Mothers with elevated depressive symptoms at hospital discharge reported more toddler externalizing behavior problems approximately 2 years later than did mothers with lower NICU discharge depression scores. Likewise, mothers reporting elevated concurrent depression also reported more externalizing behavioral problems in their toddlers compared to mothers reporting lower 24-month depressive symptoms. Maternal depression trajectories and the controls were not significant predictors of externalizing behaviors.

Toddler Internalizing Behavior Problems

Similarly, toddler internalizing behavior problems at 24 months’ postterm were predicted by maternal depression at hospital discharge, β .29 (CI.95 = −.04, .62), SE = .13, z = 2.24, p < .05, and maternal depression at 24 months, β .56 (CI.95 = .29, .83), SE = .10, z = 5.40, p < .01. Mothers with elevated depressive symptoms at hospital discharge reported more internalizing behavior problems at 24 months than did mothers reporting fewer symptoms. Elevated concurrent maternal depression also was associated with more internalizing problems at 24 months. Infant health risk, family socioeconomic status risks, and gender were not significant nor was the interaction between depression slope and infant health risk.

In sum, Table 2 indicates that initial maternal depression and maternal-depression trajectories were influenced by family sociodemographic factors. When considering child behaviors, initial maternal depression was influential in later parental reports of behavior problems, child compliance was influenced by infant medical/health risks, and child opposition was predicted by an interaction between infant medical/health risks and increasing maternal depression over time.

DISCUSSION

Mothers of infants born PT LBW are at risk for experiencing elevated psychological distress and depressive symptoms following their nonnormative birth experience (Klebanov et al., 2001). Typically, these symptoms decline over time (Poehlmann et al., 2009). A minority of mothers, however, experience increasing symptoms of depression and distress following their child’s birth, which may have implications for the development of oppositional behaviors in the most fragile PT LBW infants.

Maternal Depression and PT LBW Infant Development

In our prospective longitudinal study of children born PT LBW, we found only partial support for our hypothesis that children born earlier and with more health problems to mothers whose depressive symptoms increased over time would exhibit less compliance and more opposition during mother-child interactions. Consistent with developmental and ecological models that emphasize the importance of multiple risk factors in predicting less optimal child outcomes (e.g., Rutter, 1987; Sameroff & Fiese, 2000), toddlers who experienced more medical risks and increasing maternal symptoms exhibited the most opposition to maternal requests, a form of early dysregulated self-control (Kopp, 1982). Toddlers who experienced fewer medical risks and increasing maternal symptoms exhibited the least opposition. Compared to healthier PT LBW infants, infants born earlier and with more medical complications may be more susceptible to the social effects of maternal mood difficulties (e.g., Poehlmann & Fiese, 2001). Similarly, in their sample of typically developing and developmentally delayed 4-year-olds, Hoffman, Crnic, and Baker (2006) found that children of depressed mothers exhibited more observed dysregulation.

Although maternal depression trajectories were a key element in this study, they did not predict toddler committed compliance or maternal-reported behavior problems. Rather, neonatal health risk was a predictor of committed compliance, with more medically fragile PT LBW infants exhibiting less committed compliance than did healthier PT LBW infants. There are several possible explanations for these results. Studies of maternal depression often have focused on negative developmental outcomes (e.g., Campbell et al., 2009) rather than on outcomes that may be related to resilience processes, such as committed compliance. Moreover, many studies have not acknowledged that in some circumstances, elevated depressive symptoms and psychological distress are normative initial responses to a traumatic, nonnormative event such as the birth of a medically fragile infant. For a majority of the mothers in this study, maternal depression scores started somewhat elevated (32% in the clinically significant range and another 36% in the elevated, but subclinical, range) and then decreased over time. Campbell et al. (2009) recently found that adolescents in the study by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1999) on childcare and youth development self-reported more behavior problems and risky behaviors when mothers reported stable depressive symptoms over time (chronic, moderately elevated, and stable subclinical) compared to adolescents of mothers who were never depressed. However, teens in the latent class of mothers who showed early elevations in symptoms (postpartum and at 1 year follow-up) and later declining symptoms (2-12 years) did not show any differences in outcome measures compared to teens in the group of mothers who were never depressed.

In addition, as previous studies have illustrated, maternal reports of depressive symptoms may not always be an accurate indication of parenting behaviors. For example, Leckman-Westin, Cohen, and Stueve (2009) reported that positive responsive parenting in mothers with elevated depression mitigated later childhood behavior problems. Thus, it is important to examine the role of parenting behaviors in this process in future investigations. It also is important to consider the possibility that in samples of high-risk infants, infant characteristics such as medical fragility may be more strongly associated with development of compliance, with more medically fragile infants at a disadvantage compared to healthier PT LBW infants.

Although depression trajectories were not associated with toddler behavior problems, maternal depressive symptoms at NICU discharge and at 24 months predicted toddler internalizing and externalizing problems. It is possible that mothers with the highest initial symptoms continued to report elevated symptoms relative to other mothers during the toddler period despite the experience of a declining individual trajectory. Thus, early screening of mothers of medically fragile infants to identify those with the highest depression scores instead of documenting patterns of symptoms over time may be a more useful approach for early identification of PT LBW children who are at risk for developing behavior problems. Our findings suggest that efforts to intervene if mothers show elevated depressive symptoms during the child’s NICU stay, especially when infants experience medical complications, should be investigated in future studies with high-risk infants. In a national study of Early Head Start, intervention impact was strongest for families in which the mothers were depressed (Robinson & Emde, 2004), suggesting that comprehensive services that start early may be appropriate for such families. For families with few mental health resources, supporting the entire family unit with other resources may be a good option, as previous studies have found that women who reported more support (or who perceived more support), including financial, familial, and respite care, reported fewer depressive symptoms (Turner, 2007; Vigod, Villegas, Dennis, & Ross, 2010).

These findings suggest that postnatal maternal-depression screening (using instruments such as the CES-D) should be explored as a means to help identify infants at increased risk for externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Follow-up screening (e.g., at well-baby exams), coupled with a cumulative understanding of the child’s medical history, may inform a clinician’s understanding of later developmental concerns that may arise around children’s opposition to parental requests.

Importance of Infant and Contextual Risks

Our analyses also revealed associations between toddler compliance and neonatal health risks and gender. In this sample of children born PT LBW, neonatal health was a significant predictor of children’s compliance within the context of a parent-led cleanup task, although neonatal health did not predict mother-reported behavior problems. We suggest that early committed compliance may be protective for high-risk infants as they grow older. In contrast, dysregulated self-control, as evidenced through more opposition to maternal requests during the toddler period, may be one potential developmental pathway linking prematurity with later behavior problems in the context of maternal depressive symptoms. We are continuing to follow this sample to explore this and other developmental pathways within the family context. Because previous research has found elevated behavior problems in children born PT LBW, especially for children born earlier and with lower birth weights (Bhutta et al., 2002), it is important for future research to examine toddler oppositional behaviors as well as continuing maternal depressive symptoms as potential contributors to subsequent behavior problems in children born PT LBW. Future studies also could examine early committed compliance as a possible protective factor.

We also found that boys exhibited more opposition to maternal requests than did girls in our sample of PT LBW infants. This finding is consistent with previous research that has focused on gender differences in such skills (e.g., Kochanska et al., 2000). Given these findings, it is possible that boys born PT LBW may be at higher risk for developing problems associated with externalizing or oppositional behaviors compared to girls. In contrast, it is possible that girls born PT LBW may be at risk for experiencing inhibition or anxiety, withdrawal, and inattention as they reach school age. We are following these children at school age to determine how early compliance and opposition relate to children’s later behavioral patterns.

Finally, our results highlight the importance of the socioeconomic context for infants born PT LBW and their families, similar to the findings of previous studies of high-risk infants (e.g., Bhutta et al., 2002). Mothers who experienced more risks such as poverty, unemployment, and giving birth as a teen were the most likely to report elevated depressive symptoms prior to NICU discharge and to have increasing depression trajectories over time, similar to the results of our previous analyses (Poehlmann et al., 2009) and longitudinal studies with full-term infants (Campbell et al., 2009; Campbell, Matestic, von Stauffenberg, Mohan, & Kirchner, 2007). These findings have implications for the screening of PT LBW infants on the basis of family risk factors, including the types of interventions offered within communities, consistent with transactional theories of development that emphasize how cumulative risks may influence development over time.

LIMITATIONS

Although we had a low attrition rate across 2 years for a sample of high-risk infants, families that remained in the study were slightly more socioeconomically advantaged than were ones who dropped out of the study or could not be located. Thus, appropriate caution should be used in generalizing our findings to more socioeconomically stressed families with PT LBW infants. In addition, because we focused on infants born PT LBW who did not experience significant neurological findings during the NICU stay, our results are not generalizable to all PT LBW infants or low-risk infants born at term. Lack of inclusion of a full-term comparison group is an additional weakness, as we are unable to address issues related to toddler compliance in full-term infants. In addition, while the high correlations among birth weight, gestational age, and neonatal health risks support combining them into a composite index, in doing so we were not able to determine whether gestational age, birth weight, or specific neonatal health risks (e.g., sepsis, retinopathy of prematurity, respiratory distress syndrome) had differential effects on toddlers’ behaviors. Miceli et al. (2000) found that the effect of infant birth status on children’s outcomes at 4 and 13 months was mediated by infant medical complications, although this association decreased by 3 years of age. Also note that several measures relied on maternal report, and thus shared method variance may have led to spurious positive findings (e.g., maternal reports of depressive symptoms and toddler behavior problems). However, our use of observer ratings of toddler compliance and opposition to maternal requests was a strength of the study, in addition to the prospective longitudinal design. We also relied on self-reports of depressive symptoms rather than on diagnoses of maternal depression. Because maternal reports on depression-screening measures also can reflect more general psychological distress or anxiety (Boyd, Le, & Somberg, 2005; DiPietro, Costigan, & Sipsma, 2008), this should be considered when interpreting our results. We were unable to examine toddler situational compliance as an outcome because of limited variability in the measure, perhaps due to the normative nature of situational compliance in 2-year-olds. In addition, we did not examine maternal behaviors during cleanup or prior to cleanup as part of this analysis. Finally, children’s compliance with caregivers other than the mother was not assessed. Compliance or opposition during interactions with fathers and other caregivers would be important to examine in future studies of PT LBW infants.

Despite these limitations, this investigation provides valuable information about how maternal experiences of distress and depressive symptoms over time, neonatal health risks, and contextual factors such as poverty relate to emerging compliance, opposition, and behavior problems in PT LBW infants.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01HD44163 and P30HD03352 and a grant from the University of Wisconsin. Special thanks to the children and families who generously gave of their time to participate in this study.

Contributor Information

JULIE POEHLMANN, University of Wisconsin.

AJ MILLER SCHWICHTENBERG, University of California at Davis.

EMILY HAHN, University of Wisconsin.

KYLE MILLER, University of Wisconsin.

JANEAN DILWORTH-BART, University of Wisconsin.

DAVID KAPLAN, University of Wisconsin.

SARAH MALECK, University of Wisconsin.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for ASEBA Preschool Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi R, Yi Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 1988;16:74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Maternal depression and child behaviour problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(3):623–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Variation in susceptibility to environmental influences: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary hypothesis and some evidence. In: Ellis B, Bjorklund D, editors. Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. pp. 139–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta AT, Cleves MA, Casey PH, Cradock MM, Anand KJS. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: A meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:728–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd RC, Le HN, Somberg R. Review of screening instruments for postpartum depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2005;8:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist. 1979;34(10):844–850. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. In: Vasta R, editor. Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. JAI Press; Greenwich, CT: 1989. pp. 185–246. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Ceci SJ. Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review. 1994;101:568–586. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.101.4.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992;21(2):357–369. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Beaulieu D, Schwartz A. Hormonal sensitivity of preterm versus full-term infants to the effects of maternal depression. Infant Behavior & Development. 2008;31:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Matestic P, von Stauffenberg C, Mohan R, Kirchner T. Trajectories of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and children’s functioning at school entry. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1202–1215. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S, Morgan-Lopez A, Cox M, McLoyd V, with the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and off-spring adjustment in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(3):479–493. doi: 10.1037/a0015923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark CA, Woodward LJ, Horwood JL, Moor S. Development of emotional and behavioral regulation in children born extremely preterm and very preterm: Biological and social influences. Child Development. 2008;79(5):1444–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish AM, McMahon CA, Ungerer JA, Barnett B, Kowalenko N, Tennant C. Postnatal depression and infant cognitive and motor development in the second postnatal year: The impact of depression chronicity and infant gender. Infant Behavior & Development. 2005;28:407–417. [Google Scholar]

- Davis L, Edwards H, Mohay H, Wollin J. The impact of very premature birth on the psychological health of mothers. Early Human Development. 2003;73:61–70. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(03)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Taylor BA. Home improvements: Within-family associations between income and the quality of children’s home environments. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2007;28:427–444. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Allen MC. Estimation of gestational age: Implications for developmental research. Child Development. 1991;62:1184–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPietro JA, Costigan KA, Sipsma HL. Continuity in self-report measures of maternal anxiety, stress, and depressive symptoms from pregnancy through two years postpartum. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;29:115–124. doi: 10.1080/01674820701701546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National Vital Statistics Reports. 7. Vol. 56. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2007. Births: Preliminary data for 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman C, Crnic KA, Baker JK. Maternal depression and parenting: Implications for children’s emergent emotion regulation and behavioral functioning. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2006;6(4):271–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan D. Structural equation modeling: Foundations and extensions. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kenward MG, Molenberghs G. Likelihood based frequentist inference when data are missing at random. Statistical Science. 1998;13:236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks-Gunn J, McCormick MC. Maternal coping strategies and emotional distress: Results of an early intervention program for low birth weight young children. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:654–667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Committed compliance, moral self, and internalization: A mediational model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:339–351. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N. Mother-child mutually positive affect, the quality of child compliance to requests and prohibitions, and maternal control as correlates of early internalization. Child Development. 1995;66:236–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Coy KC, Murray KT. The development of self-regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1091–1111. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CB. Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:199–214. [Google Scholar]

- Leckman-Westin E, Cohen P, Stueve A. Maternal depression and mother-child interaction patterns: Association with toddler problems and continuity of effects to late childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50(9):1176–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. The analysis of social science data with missing values. Sociological Methods and Research. 1989;18:292–326. [Google Scholar]

- Littman B, Parmalee AH., Jr Medical correlates of infant development. Pediatrics. 1978;61:470–474. doi: 10.1542/peds.61.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon MC, Davis DW, Birkimer JC, Wilkerson SA. Predictors of depression in mothers of preterm infants. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1997;12:73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S. Births: Final data for 2004. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2006;55:1–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli PJ, Goeke-Morey MC, Whitman TL, Kolberg KS, Miller-Loncar C, White RD. Brief report: Birth status, medical complications, and social environment: Individual differences in development of preterm, very low birth weight infants. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2000;25:353–358. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.5.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MS, Holditch-Davis D, Schwartz TA, Scher M. Depressive symptoms in mothers of prematurely born infants. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2007;28:36–44. doi: 10.1097/01.DBP.0000257517.52459.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network The course of maternal depressive symptoms, maternal sensitivity, and child outcomes at 36 months. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1297–1310. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien M, Asay JH, McCluskey-Fawcett K. Family functioning and maternal depression following premature birth. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1999;17:175–188. [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Fiese BH. The interaction of maternal and infant vulnerabilities on developing infant-mother attachment relationships. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:1–11. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlmann J, Schwichtenberg AJM, Bolt D, Dilworth-Bart J. Predictors of depressive symptom trajectories in mothers of preterm or low birthweight infants. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:690–704. doi: 10.1037/a0016117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Emde R. Mental health moderators of Early Head Start on parenting and child development: Maternal depression and relationship attitudes. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2004;4:73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Fiese BH. Models of development and developmental risk. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Baldwin A, Baldwin C. Stability of intelligence from preschool to adolescence: The influence of social and family risk factors. Child Development. 1993;64:80–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Bartko WT, Baldwin A, Baldwin C, Siefer R. Family and social influences on the development of child competence. In: Lewis M, Feiring C, editors. Family, risk, and competence. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1998. pp. 161–185. [Google Scholar]

- Scott DT, Bauer CR, Kraemer HC, Tyson JE. The neonatal health index. In: Gross RT, Spiker D, Haynes CW, editors. Helping low birthweight, premature babies. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1997. pp. 341–357. [Google Scholar]

- Singer LT, Salvator A, Guo SY, Collin M, Lilien L, Baley J. Maternal psychological distress and parenting stress after the birth of a very low-birth-weight infant. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:799–805. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.9.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapolini T, McMahon CA, Ungerer JA. The effect of maternal depression and marital adjustment on young children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviour problems. Child Care Health and Development. 2007;33:794–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner H. The significance of employment for chronic stress and psychological distress among rural single mothers. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40:181–193. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census Wisconsin statistics. 2003-2005 Retrieved April 10, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/cpstc/cpstablecreator.html.

- Vigod S, Villegas L, Dennis C, Ross L. Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depression among women with preterm and low-birth-weight infants: A systematic review. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2010;117(5):540–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JW, Buka SL, McCormick MC, Fitzmaurice GM, Indurkhya A. Behavioral problems and the effects of early intervention on eight-year-old children with learning disabilities. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006;10(4):329–338. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]