The report by Matiello et al regarding a relapse of neuromyelitis optica (NMO) after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation highlights the need to further understand the role of the immune system in this disease.1 Immunosuppressive therapeutics targeting B- and T-cells are utilized to prevent disabling relapses in NMO.2 Rituximab is a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody that is reported to be effective in NMO.3 Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal anti-CD52 antibody with preliminary phase II data in multiple sclerosis, but not in NMO.4 We describe a patient with 20 relapses in 5 years despite sequential treatment with four immunomodulatory therapeutics in combination with corticosteroids and plasma exchange (PLEX) for relapses. She appeared to paradoxically worsen with profound weakness after B cell depletion with rituximab and developed tumefactive cerebral lesions after alemtuzumab.

Report

This 40 year old African-American woman presented with optic neuritis five years prior, with recovery to 20/20 after IV methylprednisolone (IVMP) (Figure). Three months later, dysesthesias in 4 extremities, mild sensory ataxia, and urinary incontinence developed. Cervical-spine MRI revealed longitudinally-extensive transverse myelitis (LETM) and serum was positive for NMO-IgG antibodies (1:1920). Treatment included IVMP for this relapse. Azathioprine and daily prednisone were added. Azathioprine was adjusted to lymphocyte counts of 500–1000 K/mm3.5 She relapsed two months later, with five total episodes of transverse myelitis in the first year, each treated with IVMP. Azathioprine was discontinued and mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice per day with daily prednisone was utilized for 18 months. She experienced four additional sensory and bladder relapses, unaccompanied by urinary tract infection. Motor testing was always normal over the first three years.

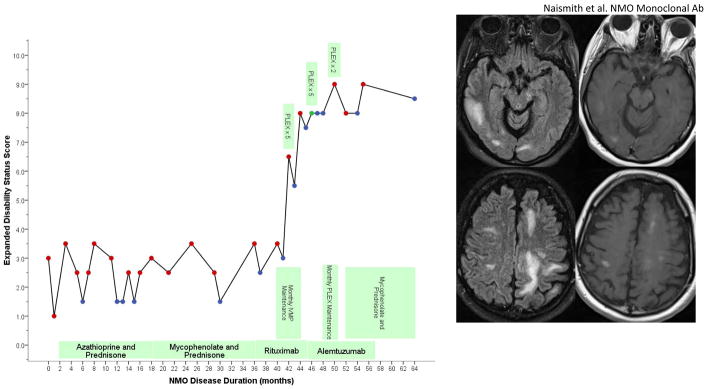

Figure.

Timeline of clinical events and treatments with Expanded Disability Status Scale. Relapses treated with IVMP are shown by red dots, relapses treated with PLEX are noted (red dots are IVMP, blue dots were non-relapse exam visits, green dot is PLEX without IVMP). After alemtuzumab, brain MRI revealed multiple, large regions of T2 signal abnormality with patchy enhancement. This included a 1.5 × 1.5 × 4 cm lesion in the right temporal lobe, a 1.4 × 1.8 × 1.2 cm lesion in the right corona radiata, and a 5.5 × 2.5 × 2.4 cm lesion in the left occipital lobe.

Due to continued disease activity, rituximab was administered. Beginning five months after rituximab, and with confirmed zero CD19+ cells, she experienced 4 additional relapses over five months, stabilizing after each. However, these culminated in persistent paraplegia.

Nine months following rituximab, B cells began to return (CD19 was 9, normal 79-545). Fourth-line treatment options were discussed due to concern for quadriplegia and respiratory compromise. Mitoxantrone was not chosen due to dose limitations and risks of cardiotoxicity and malignancy. 6,7 Cyclophosphamide was not used due to risk of infection among other side-effects. Alemtuzumab was selected to suppress mononuclear immune system cells and because it is well- tolerated with promising early results in relapsing MS. She received 5 days IV alemtuzumab at 12 mg/kg/d, with five days IVMP.

Six weeks following alemtuzumab, a relapse manifested by worsening dysesthesias culminated in apnea and intubation. MRI showed an expansile, contrast enhancing LETM. CD4 count was 30 cells/mm3 (normal 393-1607). She received PLEX and was extubated. Four months into alemtuzumab, aphasia, dysarthria, lethargy, and moderate right arm weakness developed. Brain MRI revealed three large, discreet regions of T2 signal abnormality with patchy enhancement, the largest being 33 cm3 (Figure). Thoracic cord demonstrated an enhancing expansile T2 lesion. Brain biopsy, performed to exclude opportunistic infection and malignancy, confirmed a demyelinating process. CD4 count was 133, and CD19 was 115. Over the next 5 months, she had 2 confirmed relapses and received IVMP. Mycophenolate and low-dose prednisone were added, with no further clinical relapse after 8 follow-up. She currently resides in a nursing facility, transfers with a lift, and cannot feed herself.

Comment

This case, together with the report by Matiello et al, may be instructive, as NMO disease activity continued despite marked suppression of cellular immunity. Plasma cells are the primary source of antibodies, but CD20 is not expressed by plasma cells, and CD52 is only expressed by a fraction of plasma cells. Failure to eliminate anti-aquaporin 4 antibodies may be the reason for lack of therapeutic success in each case.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Qian has received speaking honoraria from Teva Neurosciences.

Dr. Cross has received research funding, clinical trial funding, honoraria or consulting fees from the NIH, National MS Society USA, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, Genentech, Inc., Bayer Healthcare, Biogen-Idec, Hoffmann-La Roche Inc, Teva Neuroscience, Acorda Therapeutics, Serono, Pfizer, and BioMS.

Dr. Naismith has received consulting fees and speaking honoraria from Acorda Therapeutics, Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Genzyme Corporation, and Teva Neurosciences. Research funding is through the NIH.

Funding

This work was support by National Institutes of Health [T32NS007205 to PQ, K23NS052430-01A1 to RTN, K24 RR017100 to AHC]; Manny and Rosalyn Rosenthal-Dr. John L. Trotter Chair in Neuroimmunology (AHC).

This publication was made possible by Grant Number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

This is a commentary on article Matiello M, Pittock SJ, Porrata L, Weinshenker, BG. Failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to prevent relapse of neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(7):953-5.

Footnotes

All Co-Authors reviewed the manuscript. Co-author disclosure forms were obtained from all authors. All authors have agreed to conditions noted on the Author Disclosure Form.

The corresponding author takes full responsibility for the data, the analyses and interpretation, and the conduct of the research. The corresponding author has full access to all the data and has the right to publish any and all data, separate and apart from the attitudes of the sponsor.

All authors agree to the Author Disclosure Form.

References

- 1.Matiello M, Pittock SJ, Porrata L, Weinshenker BG. Failure of Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation to Prevent Relapse of Neuromyelitis Optica. Arch Neurol. 2011 Mar 14; doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.38. 2011:archneurol.2011.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wingerchuk DM, Weinshenker BG. Neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2003 Mar 11;60(5):848–853. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049912.02954.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob A, Weinshenker BG, Violich I, et al. Treatment of Neuromyelitis Optica With Rituximab: Retrospective Analysis of 25 Patients. Arch Neurol. 2008 Nov 1;65(11):1443–1448. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.noc80069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alemtuzumab vs. Interferon Beta-1a in Early Multiple Sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(17):1786–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bichuetti DB, Lobato de Oliveira EM, Oliveira DM, Amorin de Souza N, Gabbai AA. Neuromyelitis Optica Treatment: Analysis of 36 Patients. Arch Neurol. 2010 Sep 1;67(9):1131–1136. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstock-Guttman B, Ramanathan M, Lincoff N, et al. Study of Mitoxantrone for the Treatment of Recurrent Neuromyelitis Optica (Devic Disease) Arch Neurol. 2006 Jul 1;63(7):957–963. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim S-H, Kim W, Park MS, Sohn EH, Li XF, Kim HJ. Efficacy and Safety of Mitoxantrone in Patients With Highly Relapsing Neuromyelitis Optica. Arch Neurol. 2010 Dec 13; doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.322. 2010:archneurol.2010.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]