Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and deep hypothermic circulatory arrest followed by postbypass recovery on the phosphorylation state of transcription factor, cyclic adenosine 3′, 5′-monophosphate response element– binding protein (CREB), in the striatum of neonatal brain.

Methods

Neonatal piglets (1.4 to 2.5 kg) anesthetized with isoflurane and fentanyl were put on CPB. The animals were cooled to 18°C during a 20-minute period. The CPB circuit flow was then either reduced to 20 mL · kg−1 · min−1 for 90 minutes (low-flow CPB) or turned off for 90 minutes (deep hypothermic circulatory arrest), following with a gradual increase in the flow and rewarming during a 30-minute period and a 2-hour recovery. At the end of the recovery period, the animals were rapidly euthanized, and the striata were removed and frozen for immunochemical analysis by Western blot technique using antibodies against phosphorylated and total CREB. The results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (p < 0.05 was significant).

Results

Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest did not result in alteration in either the level of CREB or its degree of phosphorylation in the piglet striatum whereas after low-flow CPB, CREB phosphorylation was significantly increased (p < 0.005) and there was also an increase in CREB expression (p < 0.01).

Conclusions

This study indicates that at 2 hours of recovery, low-flow CPB but not deep hypothermic circulatory arrest causes an increase in CREB phosphorylation and expression. Future studies will determine the degree to which the increase in CREB phosphorylation correlates with cell survival and neuronal injury after CPB.

Many studies have shown that, during neonatal cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) and postbypass recovery, complex and interrelated biochemical alterations occur that can ultimately result in neuronal death. The extent of the alterations, and therefore the risk of neuronal death, are primarily related to degree and duration of the cerebral hypoxia that occurs and the conditions during the recovery process.

Exposure of the brain to hypoxia causes the death of vulnerable neurons in adults and neonates by two mechanisms: apoptosis (programmed cell death) or necrosis [1– 4]. In neonates, apoptosis might be favored over necrosis after hypoxia-ischemia [2]. Similarly, Yue and colleagues [5] suggested that immature neurons might be more prone to apoptotic death whereas terminally differentiated neurons die by necrosis. In a deep hypothermic cardiac arrest (DHCA) model, newborn piglets displayed neurologic deficits and had histologic evidence of brain damage by 6 hours after the start of reperfusion [6]. This rapid onset of cell death is consistent with apoptosis, which can kill a cell in 2 to 3 hours [7, 8]. Other studies also proposed that hypothermic CPB and DHCA trigger a complex of biochemical alterations that can ultimately lead to cell necrosis or apoptosis [9 –13].

The goal of the present study was to determine the effects of low-flow CPB (LFCPB) and DHCA on phosphorylation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (AMP) response element– binding protein (CREB) in the striatum of newborn piglets. Cyclic AMP response element–binding protein is critical for a variety of cellular processes, including proliferation, differentiation, and adaptive responses. Neuronal survival in vulnerable areas of the brain after ischemia has been associated with activation (through phosphorylation) of CREB, whereas neuronal death was preceded by a decrease in phosphorylation of CREB [14 –16]. One suggested mechanism for the prosurvival action of phosphorylated CREB is induction of B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) [16] and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [17, 18], two antiapoptotic proteins. Regulation of CREB phosphorylation and expression may therefore represent possible protective mechanisms for cell survival after CPB surgery.

Material and Methods

Animal Model

A total of 21 newborn piglets, 2 to 4 days of age (1.4 to 2.5 kg) were randomly assigned to either control-sham (n = 6), LFCPB (n = 7), or DHCA (n = 8) groups. A total of 15 animals underwent 90 minutes of DHCA (n = 8) or LFCPB (n = 7), and then were allowed to recover for 2 hours before termination of the experiment. The results in the control and LFCPB groups were more reproducible than for the DHCA group; therefore, a larger number of animals was used in the DHCA group. The control animals did not undergo CPB; they were anesthetized and only had a “sham” operation. All CPB protocol and techniques used during this study have been described in detail previously [19]. Briefly, after induction with halothane, a tracheotomy was performed, the piglets were placed on a ventilator, and anesthesia was maintained with fentanyl. After a 1-hour stabilization period, CPB was performed. All animal procedures were in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and have been approved by the local animal care committee.

Cardiopulmonary Bypass Technique and Experimental Protocol

Full CPB flow was set at 150 mL · kg−1 · min−1. Alpha-stat strategy was used in all CPB piglets to mimic the clinical procedure used in the operating room. Anesthesia was maintained during CPB using isoflurane at 0.5 to 1.0 volumes percent, pancuronium boluses of 0.1mg/kg (intravenous), and a fentanyl infusion of 10 μg · kg−1 · hr−1 (intravenous).

Low-Flow Hypothermic Cardiopulmonary Bypass

Once CPB was begun, the animals were cooled to a nasopharyngeal temperature of 18°C during 20 to 25 minutes. Ventilation was stopped shortly after initiation of CPB. When the temperature reached 18°C, the CPB circuit flow was reduced to 20 mL · kg−1 · min−1. After 90 minutes of LFCPB, the flow was gradually increased again to 150 mL · kg−1 · min−1, and the piglets were rewarmed to a temperature of 36°C during a 30-minute period.

Deep Hypothermic Cardiac Arrest

After cooling to a nasopharyngeal temperature of 18°C, the CPB pump was turned off. After circulatory arrest for 90 minutes, CPB was gradually resumed at 150 mL · kg−1 · min−1, and the piglet was rewarmed as described above.

After LFCPB or DHCA, recovery was continued for 2 hours after which the animals were euthanized by intravenous injection of 4 mol/L KCl (5 mL/kg). The striata were dissected and frozen for later analysis of CREB.

Measurements of Oxygen Pressure and Oxygen Distribution by the Oxygen-Dependent Quenching of Phosphorescence

The cortical oxygen pressure was measured using oxygen-dependent quenching of phosphorescence as described in an earlier publication [19]. Briefly, a near infrared oxygen sensitive phosphor (Oxyphor G2; Oxygen Enterprises, Ltd, Philadelphia, PA) was injected intravenously at approximately 1.5 mg/kg. The measurements were made using a multifrequency phosphorescence lifetime instrument. The excitation light (635 nm), modulated by the sum of 84 sinusoidal waves with frequencies spanning between 100 Hz and 40 kHz, was carried to the tissue through a 4-mm light guide. The phosphorescence (maximum wavelength, 790 nm) emitted from the tissue was collected through a second light guide, placed against the tissue at a distance of approximately 8 mm from the excitation light guide. This positioning of the light guides allowed effective sampling of brain tissue oxygenation down to approximately 6 mm under the neocortical surface. The phosphorescence was optically filtered, and the signal from the detector was amplified, digitized, and analyzed to give oxygen distribution in the volume of tissue sampled by the light.

Western Blot Analysis

Frozen striata were homogenized in 2% sodium dodecylsulfate, and boiled for 5 min after addition of sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer. Protein concentration was determined in homogenate samples with a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Chemical Co, Rockford, IL). An equal amount of protein from each sample was separated by 12% sodium dodecylsulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond C; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Membranes were then incubated in a blocking solution (Blotto: phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 5% nonfat milk powder) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were then incubated with anti-phosphorylated CREB antibodies (a-p-CREB; Upstate, Lake Placid, NY; 1:200) at 4°C overnight. The membranes were then washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated for 1 hour with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:1000; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Immunoreactivity was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Western Lightning kit; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA). After that, the membranes were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated in a stripping solution (62.5 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% sodium dodecylsulfate, 100 mmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol) at 50°C for 30 minutes as recommended by the enhanced chemiluminescence reagents manufacturer. The stripped membranes were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.05% Tween 20 and incubated in Blotto for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were then incubated with anti-CREB antibodies (a-CREB; Upstate; 1:400) at 4°C overnight. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 0.05% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated for 2 hours with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:1000). Immunoreactivity was detected using the enhanced chemiluminescence reaction as described above.

Data Analysis

Digital images of Western blots were analyzed by densitometry using Scion Image (Scion Image version 4.0.2; Scion, Frederick, MD). The data were normalized to the values obtained for the untreated control group (assigned a value of 1.0). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Mann-Whitney U test. A probability value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis of the physiologic variables was performed using unpaired Student’s t test. A probability value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Circulatory Arrest on Physiologic Variables and Cortical Oxygen Pressure in Newborn Piglets

During LFCPB the pH of the arterial blood increased from 7.43 ± 0.05 to 7.65 ± 0.10 (p < 0.05), but during rewarming and postbypass recovery, arterial pH was not significantly different from the control group (Table 1). The blood pressure decreased from 81 ± 5 mm Hg (control) to 18 ± 3 mm Hg (p < 0.005) at the end of CPB and stayed significantly below control to the end of recovery. Arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide decreased significantly during cooling and LFCPB, whereas arterial partial pressure of oxygen significantly increased during cooling. Control oxygen pressure (pre-bypass) was 58.4 ± 9.6 mm Hg and during LFCPB this decreased to 10.4 ± 1.8 mm Hg (p < 0.005). During the recovery period, cortical oxygenation increased to values not significantly different from control values.

Table 1.

Physiologic Variables of Newborn Piglets During Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass and Recovery

| Experimental Conditions | Heart Rate (beats/min) | pHa | PaCO2 (mm Hg) | PaO2 (mm Hg) | MABP (mm Hg) | Cortical Oxygen (mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prebypass | 208 ± 26 | 7.43 ± 0.05 | 34.3 ± 5.0 | 122.8 ± 42.1 | 81 ± 5 | 58.4 ± 9.6 |

| Bypass | ||||||

| Cooling | 48 ± 1c | 7.53 ± 0.14 | 24.9 ± 4.3a | 214.9 ± 39.1b | 61 ± 6a | 35.6 ± 11a |

| LFCPB | 0 | 7.65 ± 0.10a | 16.0 ± 6.9b | 177.0 ± 44.5 | 18 ± 3c | 10.4 ± 1.8c |

| Warming | 199 ± 31 | 7.50 ± 0.08 | 28.1 ± 5.2 | 145.4 ± 27.2 | 65 ± 9a | 47.1 ± 8.0 |

| Recovery | ||||||

| 1 hour | 207 ± 43 | 7.47 ± 0.05 | 27.1 ± 6.6 | 166.7 ± 97.3 | 62 ± 8a | 46.9 ± 11.5 |

| 2 hour | 207 ± 42 | 7.45 ± 0.09 | 29.3 ± 6.3 | 132.7 ± 55.5 | 66 ± 10a | 47.0 ± 14.2 |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.005.

The data are the mean ± standard deviation for 7 experiments.

LFCPB = low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass; MABP = mean arterial blood pressure; PaCO2 = arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2 = arterial partial pressure of oxygen; pHa = arterial pH.

As shown in Table 2, arterial pH and partial pressure of carbon dioxide for newborn piglets during DHCA were not significantly different from control. There was no detectable blood pressure during DHCA. During rewarming and the 2-hour recovery period, blood pressure was not significantly different from prebypass values. Cortical oxygen decreased during DHCA from 62.9 ± 10.2 mm Hg to 1.3 ± 0.6 mm Hg (p < 0.005) and during rewarming and recovery increased to about 40 mm Hg.

Table 2.

Physiologic Variables of Newborn Piglets During Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest and Recovery

| Experimental Conditions | Heart Rate (beats/min) | pHa | PaCO2 (mm Hg) | PaO2 (mm Hg) | MABP (mm Hg) | Cortical Oxygen (mm Hg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prebypass | 203 ± 39 | 7.46 ± 0.07 | 36.9 ± 3.3 | 126.1 ± 27.2 | 71 ± 18 | 62.9 ± 10.2 |

| Bypass | ||||||

| Cooling | 63 ± 53c | 7.48 ± 0.15 | 32.3 ± 13.1 | 206.1 ± 53.9a | 59 ± 11 | 37.9 ± 14.5b |

| DHCA | 0 | 0 | 1.3 ± 0.6c | |||

| Warming | 215 ± 21 | 7.38 ± 0.08 | 32.9 ± 6.5 | 175.7 ± 32.9 | 68 ± 18 | 42.0 ± 6.5a |

| Recovery | ||||||

| 1 hour | 180 ± 24 | 7.39 ± 0.13 | 30.6 ± 5.9 | 210.3 ± 161.3 | 67 ± 13 | 39.9 ± 8a |

| 2 hour | 204 ± 36 | 7.37 ± 0.14 | 35.4 ± 10.8 | 190.1 ± 102.8 | 65 ± 9 | 45.6 ± 7.6a |

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.005.

The data are the mean ± standard deviation for 8 experiments.

DHCA = deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; MABP = mean arterial blood pressure; PaCO2 = arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2 = arterial partial pressure of oxygen; pHa = arterial pH.

Levels of Phosphorylated Cyclic AMP Response Element Binding Protein in Striatal Tissue Measured After 2 Hours of Recovery After Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest and Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass

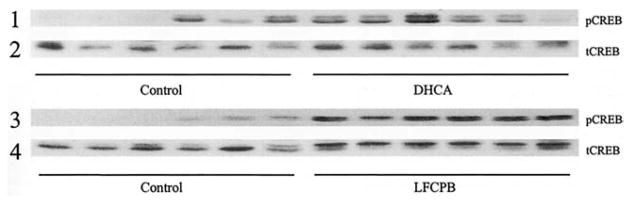

Western blots of proteins isolated from striatal tissues of piglets from the control group and groups subjected to DHCA and to LFCPB were probed with a-p-CREB antibodies (Fig 1). The phospho-CREB immunoreactivity in striata from animals that underwent DHCA plus 2 hours of postbypass recovery was found to be not statistically significant when compared with the sham-operated group of animals (193% ± 86% versus 100% ± 63%; Fig 1, row 1). In contrast, there was an increase in phospho-CREB immunoreactivity (682% ± 130%) in the striata from LFCPB animals, and this was statistically significant when compared with both sham-operated (100% ± 63%; p < 0.005) and DHCA (p < 0.005) groups (Fig 1, row 3).

Fig 1.

Immunoblots of striatal samples probed with antibodies against phosphorylated and total cyclic AMP response element–binding protein (CREB). Western blots for control, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) and low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass (LFCPB) piglets, probed with either anti-phosphorylated CREB antibodies (pCREB, rows 1 and 3) or with anti-CREB antibody (tCREB, rows 2 and 4), are shown.

Levels of Total Cyclic AMP Response Element Binding Protein in the Striatum After Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest and Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass and 2 Hours of Recovery

The increase in phospho-CREB after LFCPB could be caused by either phosphorylation of existing CREB, resulting in a decrease of nonphosphorylated CREB and an increase in the phosphorylated-to-dephosphorylated CREB ratio, or an increase in the total CREB with little change in the phosphorylated-to-dephosphorylated ratio. To determine whether the total amount of CREB was altered, CREB in the striatal tissue was measured with an antibody that equally recognized both phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated CREB (anti-CREB antibody). The measurements of total CREB show that DHCA did not result in a significant increase in CREB compared with control (96% ± 19%; Fig 1, row 2), whereas LFCPB did induce a statistically significant increase as compared with control (162% ± 63%; p < 0.01; Fig 1, row 4). Total CREB immunoreactivity after LFCPB was also significantly higher than that measured after DHCA (p < 0.01).

Ratio of Phosphorylated to Dephosphorylated Cyclic AMP Response Element Binding Protein in the Striatum After Deep Hypothermic Circulatory Arrest and Low-Flow Cardiopulmonary Bypass and 2 Hours of Recovery

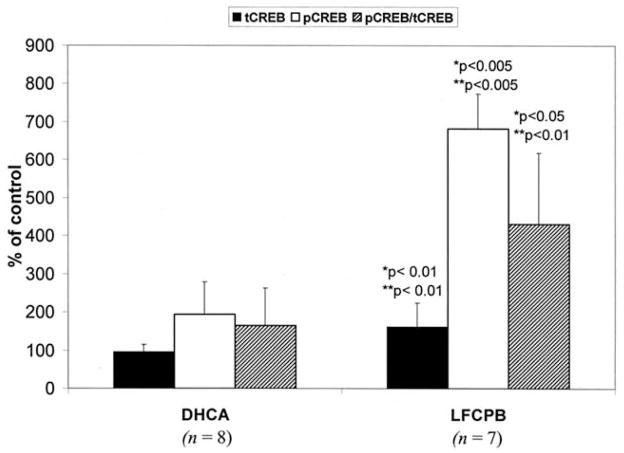

To determine the extent to which the ratio of phosphorylated to dephosphorylated CREB was altered, phospho-CREB levels were normalized to the total CREB. As can be seen in Figure 2, after normalization the fraction of the total CREB that is phosphorylated is significantly higher after LFCPB as compared with the sham-operated or DHCA groups (431% ± 187% versus 100% ± 112%; p < 0.05; or 165% ± 97%; p < 0.01). This means that after LFCPB, the elevated levels of phospho-CREB were the result of both an increased level of CREB protein and an increase in the phosphorylated-to-dephosphorylated CREB ratio. Thus, after LFCPB, but not DHCA, both total CREB and the fraction that is phosphorylated were significantly enhanced compared with control animals.

Fig 2.

Effect of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) and low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass (LFCPB) on ratio of phosphorylated (pCREB)-to-total (tCREB) cyclic AMP response element–binding protein in the striatum of newborn piglets. Data are the mean ± standard deviation for LFCPB (n = 7) and DHCA (n = 8) experiments, and are expressed as percentage of the corresponding values for the control group of piglets (n = 6). *p and **p indicate significant differences from control values and DHCA values, respectively, as determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by Mann-Whitney U test.

Comment

This study demonstrated significant increases in the levels of total and phosphorylated CREB in newborn piglet striatum after a 2-hour recovery after LFCPB, but not after DHCA. If elevated CREB phosphorylation may be a survival factor in ischemic-hypoxic injury, then increases in CREB phosphorylation suggest that LFCPB spares certain deleterious effects of DHCA.

A limitation in our study is that CREB phosphorylation was measured at only one time during the recovery period. In the DHCA model, the increase in CREB phosphorylation was not significant at 2 hours of recovery. Future experiments will characterize the time-dependent changes in CREB phosphorylation and determine the degree to which the increase in phosphorylated CREB, as measured at 2 hours, correlates with cell survival and neuronal injury. When taken together with results of our earlier study [19], however, the data suggest that patterns of CREB phosphorylation after DHCA and LFCPB are associated with severe and moderate ischemic conditions, respectively. During DHCA, brain oxygenation decreases almost to 0 mm Hg, whereas during LFCPB it decreases to about 10 mm Hg. It has also been shown that DHCA, in contrast to LFCPB, causes a massive accumulation of extracellular dopamine and an increase in hydroxyl radical production [19].

Both dopamine and hydroxyl radicals can mediate neuronal injury, particularly within the striatum. Dopamine can be oxidized during the postischemic period with the formation of free radicals and reactive, cytotoxic quinones, ultimately causing cell death [20, 21]. Both dopamine and its metabolites are shown to induce apoptosis [22, 23].

Recent studies suggest a role for CREB as a survival factor in several kinds of neuronal injury [24 –28]. Increased CREB phosphorylation during postischemic recovery has been associated with neuronal survival [15, 16]. In the striatum, severe ischemic injury caused a slight and transient activation followed by a rapid disappearance of CREB phosphorylation, which preceded ischemic morphologic changes in the neurons, whereas moderate ischemic injury was associated with persistently activated CREB phosphorylation with normally maintained morphology during the postischemic recovery [14].

The increase in CREB phosphorylation can protect neurons against ischemia-induced apoptotic cell death by activation of antiapoptotic pathways. Cell survival mediated by neurotrophin-induced CREB phosphorylation in sympathetic and cortical neurons was associated with increased expression of Bcl-2, which contains a cyclic AMP response element in the 5′ promoter region [25]. Earlier studies demonstrated that overexpression of Bcl-2 provides protection against apoptosis [29] and ischemic neuronal death [30, 31]. In hippocampal neurons, calcium– calmodulin kinase–mediated phosphorylation of CREB upregulated Bcl-2 expression 6 hours after exposure to glutamate [16]. In the same study, pretreatment of the cells with calcium– calmodulin kinase inhibitor KN93 or with cyclic AMP response element– decoy oligonucleotide inhibited glutamate-induced increased Bcl-2 production and significantly increased the level of neuronal damage compared with that in controls. This suggests that CREB activation may contribute to neuronal survival by increasing Bcl-2 production. Recent studies show that both necrotic and apoptotic neuronal death occur in vulnerable brain regions after DHCA [6, 32, 33], and predominantly necrotic death occurs after LFCPB [34]. In other investigations, CPB was shown to induce expression of apoptotic genes in the brain [35].

The exact mechanisms of differential CREB phosphorylation depending on the severity of ischemic stress are not fully understood. Phosphorylation of CREB may be activated by several kinases, including protein kinase A, protein kinase C, calcium– calmodulin kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase–activated protein kinase 2, and the pp90 ribosomal S6 kinase family [28, 36]. In global ischemia, calcium– calmodulin kinase II is rapidly inhibited [37, 38]. During postischemic recirculation, protein kinase A activity in the ischemic core is rapidly suppressed after its initial transient activation, and neuronal death eventually takes place in this region. By contrast, protein kinase A in the periischemic area is continuously activated, and neurons in this area are spared ischemic damage and survive [15]. We can hypothesize that the difference in CREB phosphorylation between DHCA and LFCPB, representing severe and moderate ischemia models, respectively, may also be the result of altered activities of these protein kinases.

An interesting observation was the increase in total CREB protein after LFCPB. This may be related to increased CREB mRNA synthesis or its stability. The CREB gene contains three cyclic AMP response element sites, suggesting that CREB gene expression may be positively autoregulated [39]. Considering the high level of activated CREB after LFCPB, this does not seem unlikely. The increase in amount of CREB protein could contribute to the elevation of phosphorylated CREB levels and thus potentiate CREB transactivation function. Upregulation of CREB protein has been shown to inhibit apoptosis in neurons [40].

In conclusion, this study shows that in piglet striatum, severe ischemia induced by DHCA and associated with acute release of extracellular dopamine and increased hydroxyl radical production does not cause a significant increase in CREB phosphorylation after a 2-hour recovery period. In contrast, LFCPB spares the effects of extracellular dopamine release and increase in hydroxyl radicals and results in a significant increase in CREB phosphorylation and expression. These results suggest that LFCPB can provide a significant degree of neuroprotection compared with DHCA, and may be of importance for clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants HL-58669 and NS 31465.

References

- 1.Bottiger BW, Schmitz B, Wiessner C, Vogel P, Hossmann KA. Neuronal stress response and neuronal cell damage after cardiocirculatory arrest in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:1077–87. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng Y, Deshumukh M, D’Costa M. Caspase inhibitor affords neuroprotection with delayed administration in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1992–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor DL, Edwards D, Mehmet H. Oxidative metabolism, apoptosis and perinatal brain injury. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:93–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishimaru MJ, Ikonomidou C, Tenkova TI, et al. Distinguishing excitotoxic from apoptotic neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1999;408:461–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue X, Mehmet H, Penrice J, et al. Apoptosis and necrosis in the newborn piglet brain following transient cerebral hypoxia-ischaemia. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1997;23:16–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurth CD, Priestly M, Golden J, McCann J, Raghupathi R. Regional patterns of neuronal death after deep hypothermic arrest. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;118:1068–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raff MC, Barres BA, Burne JF, Coles HS, Ishizaki Y, Jacobson MD. Programmed cell death and the control of cell survival: lessons from the nervous system. Science. 1993;262:695–700. doi: 10.1126/science.8235590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomaidou D, Mione MC, Cavanagh JFR, Parnavelas JG. Apoptosis and its relation to the cell cycle in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1075–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-01075.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tseng EE, Brock MV, Lange MS, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibition reduces neuronal apoptosis after hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:1639–47. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgartner WA, Redmond M, Brock M, et al. Pathophysiology of cerebral injury and future management. J Cardiac Surg. 1997;12:300–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Redmond JM, Gillinov AM, Zehr KJ, et al. Glutamate excitotoxicity: a mechanism of neurologic injury associated with hypothermic circulatory arrest. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:776–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bokesch PM, Seirafi PA, Warner KG, Marchand JE, Kream RM, Trapp B. Differential immediate-early gene expression in ovine brain after cardiopulmonary bypass and hypothermic circulatory arrest. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:961–8. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199810000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nollert G, Nagashima M, Bucerius J, et al. Oxygenation strategy and neurologic damage after deep hypothermic circulatory arrest. II. Hypoxic versus free radical injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;117:1172–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(99)70257-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka K, Nogawa S, Ito D, et al. Activated phosphorylation of cyclic AMP response element binding protein is associated with preservation of striatal neurons after focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neuroscience. 2000;100:345–54. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanaka K. Alteration of second messengers during acute cerebral ischemia—adenylate cyclase, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, and cyclic AMP response element binding protein. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:173–207. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mabuchi T, Kitagawa K, Kuwabara K, et al. Phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding protein in hippocampal neurons as a protective response after exposure to glutamate in vitro and ischemia in vivo. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9204–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09204.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schabitz WR, Schwab S, Spranger M, Hacke W. Intraventricular brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces infarct size after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:500–6. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199705000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyata K, Omori N, Uchino H, Yamaguchi T, Isshiki A, Shibasaki F. Involvement of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB pathway in neuroprotective effect of cyclosporin A in forebrain ischemia. Neuroscience. 2001;105:571–8. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schultz S, Creed J, Schears G, et al. Comparison of low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass and circulatory arrest on brain oxygen and metabolism. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:2138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Graham DG, Tiffany SM, Bell WR, Jr, Gutknecht WF. Autoxidation versus covalent binding of quinones as the mechanism of toxicity of dopamine, 6-hydroxydopamine, and related compounds toward C1300 neuroblastoma cells in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 1978;14:644–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg PA. Catecholamine toxicity in cerebral cortex in dissociated cell culture. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2887–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02887.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daily D, Barzilai A, Offen D, Kamsler A, Melamed E, Ziv I. The involvement of p53 in dopamine-induced apoptosis of cerebellar granule neurons and leukemic cells overexpressing p53. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1999;19:261–76. doi: 10.1023/A:1006933312401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emdadul Haque M, Asanuma M, Higashi Y, Miyazaki I, Tanaka K, Ogawa N. Apoptosis-inducing neurotoxicity of dopamine and its metabolites via reactive quinone generation in neuroblastoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1619:39–52. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jean D, Harbison M, McConkey DJ, Ronai Z, Bar-Eli M. CREB and its associated proteins act as survival factors for human melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24884–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riccio A, Ahn S, Davenport CM, Blendy JA, Ginty DD. Mediation by a CREB family transcription factor of NGF-dependent survival of sympathetic neurons. Science. 1999;286:2358–61. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somers JP, DeLoia JA, Zeleznik AJ. Adenovirus-directed expression of a nonphosphorylatable mutant of CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) adversely affects the survival, but not the differentiation, of rat granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1364–72. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.8.0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonni A, Brunet A, West AE, Datta SR, Takasu MA, Greenberg ME. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1358–62. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkbeiner S. CREB couples neurotrophin signals to survival messages. Neuron. 2000;25:11–4. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80866-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinou JC, Frankowski H, Missotten M, Martinou I, Potier L, Dubois-Dauphin M. Bcl-2 and neuronal selection during development of the nervous system. J Physiol (Lond) 1994;88:209–11. doi: 10.1016/0928-4257(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lawrence MS, Ho DY, Sun GH, Steinberg GK, Sapolsky RM. Overexpression of Bcl-2 with herpes simplex virus vectors protects CNS neurons against neurological insults in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. 1996;16:486–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00486.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitagawa K, Matsumoto M, Yang G, et al. Cerebral ischemia after bilateral carotid artery occlusion and intraluminal suture occlusion in mice: evaluation of the patency of the posterior communicating artery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:570–9. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tseng EE, Brock MV, Lange MS, et al. Nitric oxide mediates neurologic injury after hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ditsworth D, Priestley MA, Loepke AW, et al. Apoptotic neuronal death following deep hypothermic circulatory arrest in piglets. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1119–27. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200305000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loepke AW, Priestley MA, Schultz SE, McCann J, Golden J, Kurth CD. Desflurane improves neurologic outcome after low-flow cardiopulmonary bypass in newborn pigs. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1521–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200212000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato Y, Laskowitz DT, Bennett ER, Newman MF, Warner DS, Grocott HP. Differential cerebral gene expression during cardiopulmonary bypass in the rat: evidence for apoptosis? Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1389–94. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Impey S, Obrietan K, Wong ST, et al. Cross talk between ERK and PKA is required for Ca2+ stimulation of CREB-dependent transcription and ERK nuclear translocation. Neuron. 1998;21:869–83. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Churn SB, Yaghmai A, Povlishock J, Rafiq A, DeLorenzo RJ. Global forebrain ischemia results in decreased immunoreactivity of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:784–93. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1992.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babcock AM, Liu H, Paden CM, Edmo D, Popper P, Micevych PE. Transient cerebral ischemia decreases calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II immunoreactivity, but not mRNA levels in the gerbil hippocampus. Brain Res. 1995;705:307–14. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01155-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyer TE, Waeber G, Lin J, Beckmann W, Habener JF. The promoter of the gene encoding 3′, 5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element binding protein contains cAMP response elements: evidence for positive autoregulation of gene transcription. Endocrinology. 1993;132:770–80. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.2.8381074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walton M, Woodgate A, Muravlev A, Xu R, During MJ, Dragunow M. CREB phosphorylation promotes nerve cell survival. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1836–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]