Abstract

Using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study and Current Population Surveys, we find that labor market conditions play a large role in explaining the positive relationship between educational attainment and marriage. Our results suggest that if low-educated parents faced the same (stronger) labor market conditions as their more-educated counterparts, then differences in marriage by education would narrow considerably. Better labor markets are positively related to marriage for fathers at all educational levels. In contrast, better labor markets are positively related to marriage for less-educated mothers but not their more-educated counterparts. We discuss the implications of our findings for theories about women’s earning power and marriage, the current economic recession, and future studies of differences in family structure across education groups.

The retreat from marriage in recent decades has occurred most dramatically for those with less than a college education (Ellwood and Jencks 2004). Marriage has declined and nonmarital childbearing and divorce have increased at all education levels, but more so for those with a high school degree or less (Goldstein and Kenney 2001; McLanahan 2004; Schoen and Cheng 2006). These differences across education groups appear for both parents and non-parents but are of particular concern when children are involved. Educational differences in parents’ marital status are important because children raised by married parents enjoy a host of economic and social advantages compared with their counterparts (Brown 2004; Carlson and Corcoran 2001; Manning and Lamb 2003; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994). Further, educational differences in marital status are likely to add to the economic disadvantages faced by children as a direct result of low maternal education and to contribute to the intergenerational transmission of economic disadvantages (McLanahan 2004).

Although recent research has documented stark and widening differences in marital status by education, particularly among parents, the causes of these differences remain unclear (Ellwood and Jencks 2004). Our paper considers the importance of labor market conditions in explaining differences in marriage by education. We also consider whether the relationship between labor market conditions and marriage differs by level of education.

We take advantage of data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study to compare transitions to marriage following a nonmarital birth for mothers and fathers by their level of educational attainment. Focusing on a sample of unmarried parents provides several benefits. First, we are able to incorporate detailed characteristics of unmarried mothers and the fathers of their recent child. Prior research has often been limited to women only or to unrelated women and men rather than couples. Only half of the couples in our sample share the same broad level of education, so analyzing both mother and father’s education, and the economic circumstances that follow from these levels of education, could be important. Second, unwed parents may face stronger normative pressure to marry than couples without children (Thornton and Young-DeMarco 2001). Therefore, a focus on unmarried parents demonstrates how economic circumstances may prevent parent couples from marrying despite longstanding (although eroding) norms that dictate otherwise. Finally, unmarried parents are a group of particular policy relevance because their relationship transitions have implications for the young children they are raising. With almost 40 percent of births occurring outside of marriage (Ventura 2009), our sample of unmarried parents represents a large segment of the broader population.

Among the 3,354 unmarried couples in our sample, mothers and fathers with higher levels of educational attainment are significantly more likely to marry in the five years following a nonmarital birth. In examining these differences, we make three contributions: First, we show that labor market conditions for mothers and fathers with different levels of education account for a large portion of differences in marriage across education groups. This finding contributes to a more general sociological literature, linking macro-level environments to personal decisions. Second, we show that women’s economic opportunities have a stronger positive influence on marriage for lower educated mothers than for more highly educated mothers. This finding extends literature on the theoretical independence and income effects of women’s economic opportunities. Third, based on our findings, we predict that the current economic recession will pose a barrier to marriage, especially for parents with a high school education or less, and exacerbate existing differences in marriage by education.

Background

Individual-Level Economic Circumstances

Education may be related to marriage because of its relationship to better economic circumstances (Ashenfelter and Krueger 1994; Liming and Wolf 2008). For men in particular, research has consistently shown that earnings and employment are positively associated with marriage (Ellwood and Jencks 2004; McLanahan and Percheski 2008; Smock and Manning 1997; Sweeney 2002). Most of this research is based on national samples. The quantitative evidence for unmarried fathers is more limited but consistent with national samples (Carlson, McLanahan and England 2004; Testa et al. 1989; Zavodny 1999).

Studies dating back to the Great Depression and the Iowa Farm Crisis have shown that fathers strongly identify with the breadwinner role and the stress associated with the failure to fulfill the breadwinner role can have negative spillover effects on family relationships (Conger and Elder 1994; Elder 1974; Komarovsky 1940). Contemporary research reinforces these findings, showing that fathers are less likely to be involved with their children and the mothers of their children when they cannot live up to the male breadwinner expectation (Anderson 1990; Edin and Kefalas 2005; Furstenberg 2007). Other research suggests women do not view men, including the fathers of their children, as marriageable unless they have steady employment (Edin 2000; Edin and Kefalas 2005; Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan 2005; Smock, Manning and Porter 2005; Wilson 1987).

For couples, employment and earnings from either partner may facilitate marriage by increasing economic stability. Qualitative research finds that financial stability is an important pre-requisite for marriage. Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan (2005) find that unmarried parents consistently express a need for financial stability and a desire to achieve economic benchmarks such as a downpayment on a home or a wedding before they will marry. Smock, Manning and Porter (2005) find a similarly strong emphasis on financial pre-requisites for marriage in their study of cohabiting couples.

In contrast with fathers, for whom earning power facilitates marriage, the relationship between mothers’ own earnings and marriage is theoretically ambiguous. In theory, mothers’ employment and earnings could have a positive influence on marriage by increasing a couple’s income, economic stability, and ability to set up an independent household. This pro-marriage influence of women’s employment and earnings is referred to in the literature as an “income effect.” Alternatively, mothers’ employment and earnings could substitute for the financial support or contribution of a husband, reducing the economic necessity of marriage for mothers, thereby delaying or decreasing marriage. This marriage-inhibiting effect is referred to in the literature as an “independence effect” (Hannan, Tuma and Groeneveld 1977; Oppenheimer 1988).

Research in the past decade has tended to find a positive relationship between women’s employment and earnings and marriage, consistent with the theoretical income effect (Gassman-Pines and Yoshikawa 2006; Sweeney 2002; Sweeney and Cancian 2004; White and Rogers 2000). The limited research focused on mothers is partially consistent with research on all adult women. Carlson, McLanahan and England (2004) find that unmarried mothers’ employment is not related to marriage, but, when employed, unmarried mothers’ earnings are positively related to marriage. Therefore, motherhood may dampen or eliminate the positive relationship between women’s employment and transitions to marriage. However, among women who are employed (be they mothers or women in the general population), higher earnings have a positive relationship with marriage.

In measuring economic circumstances, employment status and earnings are clearly central, but poor health and problems with drug or alcohol use are also components of human capital. Poor health and drug or alcohol problems could contribute to educational differences in marriage if these circumstances are a barrier to marriage and more common among low-educated parents. Prior research demonstrates that health and drug and alcohol use are negatively associated with marriage (Carlson, McLanahan and England 2004; Lillard and Panis 1996), but marriage may be a cause as well as a consequence of these conditions (Duncan, Wilkerson and England 2006; Waite 1995).

Interpreting the relationship between individual-level economic circumstances and marriage is complicated by ambiguity in causal ordering. Employment, income, health, and drug use may all be both predictive of marriage and also influenced by marriage (Waite 1995). The causal direction is further complicated because behavior may be affected by anticipated marital status. For instance, labor supply may be influenced by the anticipation of a marriage or divorce (Johnson and Skinner 1986; Rogers 1999). Studying macro-level environments such as labor markets avoids these ambiguities. In the next section, we turn to prior research on labor market conditions, which may influence individual marriage decisions but are exogenous with respect to these marriage decisions.

Economic Opportunities in the Local Labor Market

There is a long tradition in sociological research of linking macro-level context, such as country, province, neighborhood, or school, with individual-level behavior including marriage decisions (Coleman 1990; Durkheim 1997[1897]; Entwisle 2007; Guttentag and Secord 1983; Sampson and Groves 1989). In this same vein, several strands of literature suggest that labor markets may influence marriage in a variety of ways.

Analyzing labor market influences on marriage has two benefits over an exclusively individual-level approach. First, labor market conditions are exogenous with respect to marriage decisions, but individual-level economic circumstances are not. Second, labor market conditions may capture a bundle of economic influences that are difficult to observe in full at the individual level. In weak labor markets, mothers and fathers may be more likely to experience unemployment, wage and benefits stagnation or decline, insufficient work hours, and fewer opportunities for career advancement (Voydanoff 1990). Even couples who would like to get married may delay their marriage plans in the face of unemployment, economic backsliding, or underemployment. Further, even among those who are employed full-time, feelings of uncertainty about one’s own or one’s partner’s economic future can be expected to delay marriage plans. Therefore, labor markets may have influences that go beyond employment status and earnings level.

Labor market conditions may shape expected future economic circumstances. Theoretically, marriage decisions are made based on the anticipation of future conditions within marriage, among which economic security is an important consideration (Oppenheimer 1988; Xie et al. 2003). Prior research has found that men with better future economic prospects are more likely to marry (Xie et al. 2003).

Prior research has not examined the relationship between labor market conditions and educational differences in marriage in particular; however, research on the Great Depression suggests that marriage rates are positively associated with favorable macroeconomic conditions (Cherlin 1992; Ogburn and Nimkoff 1955; Ogburn and Thomas 1922). Research in more recent decades has also found a positive relationship between favorable labor market conditions and marriage and vice versa. Using data covering the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, Lichter, McLaughlin and Ribar (2002) find that the erosion of economic opportunities led to lower rates of marriage for young, low-educated women. Using different data and methods, a study by Blau, Kahn and Waldfogel (2000) found that better male labor market conditions were associated with marriage for young women in all education groups. Studies of counties or metropolitan statistical areas have tended to find that areas with better economic opportunities for women have lower rates of ever marrying (e.g., Blau, Kahn and Waldfogel 2000; Ellwood and Jencks 2004), suggesting that the independence effect dominates. Our paper extends this prior research by focusing on parent-couples, using more recent data, and using labor market measures stratified by gender and education as well as locality.

Labor Market Influences on Marriage for Different Education Groups

Prior research on women’s economic opportunities and marriage has typically not considered the possibility that the income effect may dominate in some contexts or for some subgroups of women and the independence effect may dominate in other settings and for other subgroups. Although a few studies have considered whether the income and independence effects vary by geographic location (Hannan, Tuma and Groeneveld 1977; Harknett and Gennetian 2003; Ono 2003), none has considered whether the income and independence effects vary by level of educational attainment. However, prior research suggests that low-income parents, who tend to have lower levels of education, place a heavy emphasis on the economic benefits of marriage (Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan 2005; Edin and Kefalas 2005). Our own descriptive analyses based on our Fragile Families sample of unmarried parents accords with this prior research, showing that less-educated parents place more emphasis on economic security and men’s and women’s steady employment as pre-requisites for marriage than their more-educated counterparts (available upon request). Given prior research and these attitudinal differences, we might expect that the pro-marriage income effect of women’s economic opportunities may be stronger for less educated mothers than for their more educated counterparts.

Data and Methods

The microdata for our paper come from the longitudinal Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study, which follows a birth cohort of 4,898 children born in 20 large U.S. cities. We focus on the oversample of unmarried parents included in the study. The 20 cities for the study were randomly selected from strata defined by labor market and policy characteristics, providing the opportunity to analyze how different labor market contexts influence marital transitions. The sample is representative of births to unmarried parents in cities with populations of 200,000 or more. Baseline interviews with mothers were completed in the hospital shortly after the birth, between 1998 and 2000. Fathers were also interviewed after the birth, either at the hospital or as soon as possible afterwards.

We use data from the mothers’ and fathers’ baseline surveys, and follow-up surveys at one, three, and five years after the birth. The baseline survey response rate of 87% for unmarried mothers represents the percent of eligible mothers approached in hospitals who responded to the baseline survey. The follow-up survey response rates of 90, 88, and 87% for unmarried mothers represent the percent of mothers in the baseline survey who responded to the one, three, and five year follow-up surveys, respectively. The baseline survey response rate of 75% for unmarried fathers is relative to completed mother baseline interviews. The follow-up survey response rates of 71, 69, and 67% for unmarried fathers represent the percent of fathers in the baseline survey who responded to the one, three, and five year follow-ups, respectively. In the Fragile Families study, weaker parent relationships are associated with survey non-response. Our non-response analysis finds that our sample underrepresents mothers with less than a high school education. Given that non-respondents are probably less likely to marry, we expect that non-response leads us to slightly underestimate the differences in marriage by education.

After our sample exclusions, our analysis is based on 3,354 parent-couples, representing just over 90% of the original unmarried sample in the Fragile Families study. We observe these couples for an average of 51 months before they marry or are censored. Our event history analysis is based on 169,991 person-months of data. To maximize the sample included in our analysis, mother proxy reports were used when father responses were not available. In separate analyses (not shown), we find that our results are consistent when we exclude the 9 percent of couples in which the father was never interviewed. We exclude cases that are missing information on mother or father’s education (n=200) or marriage (n=156). Missing data on covariates were imputed using a regression-based imputation approach, and the results presented are consistent with results based on listwise deletion.

Dependent Variable

Our analysis models the hazard of marriage to the other parent using event history models. We focus on marriage to the other parent because children raised by two biological parents fare better than children raised by one biological and one step parent (Cavanagh and Huston 2006; Fomby and Cherlin 2007; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Osborne and McLanahan 2007). Another reason for this focus is that we want to test the role of both mothers’ and fathers’ economic circumstances and labor market prospects in marriage transitions, and we lack complete information for new partners. In our sample and time frame, approximately 5% of mothers married a new partner. In our analysis, mothers who married a new partner are not distinguished from other mothers who remained unmarried to the baby’s father. As a sensitivity test, we repeated all of our analyses omitting mothers who married other partners during the follow-up and using mothers’ marriage to any partner (rather than just fathers) as the dependent variable. In each case, the overall pattern of results remains similar to those presented.

Duration is measured from the time of the birth until the exact month of marriage or censoring, and is measured in person-months. We imputed marriage dates for 97 respondents with missing data to be the midway point between the last interview in which they indicated they were unmarried and the first interview in which they indicated they were married. We imputed a marriage month of June for four respondents. In a sensitivity analysis, we find that our results do not differ when we impute missing marriage dates as the month before the interview in which the marriage was reported.

Independent Variables

Mothers’ and fathers’ education is divided into four groups: less than high school, high school or GED, some college, and bachelor’s degree or higher. The some college group is somewhat heterogeneous, including those with some college, technical, or vocational education beyond high school.

Mothers’ and fathers’ educational attainment were measured in each survey wave. For educational attainment and a number of other measures updated at each survey wave, we code changes between survey waves as if they occurred at the midway point between the two waves. The inexact timing of changes in this and other individual-level variables is a limitation of our data. However, sensitivity analyses in which changes are coded as if they occurred in the month prior to the latter wave generally yield consistent results.

Explanatory Variables

We include four individual-level measures of economic circumstances for mothers and fathers: employment, income-to-poverty ratios, a dichotomous indicator of self-reported fair or poor health, and a dichotomous indicator of self-reported drug or alcohol problems.

The measure of mothers’ employment at baseline is based on a question that asks mothers whether they were employed in the year prior to the birth. Otherwise, employment measures are based on questions that asked mothers and fathers whether they were employed in the prior week. Mothers’ employment was the only time-varying variable that was sensitive to assumptions about the timing of changes in status, a point to which we return in the Results section. The income-to-poverty ratios are the ratio of household income to the official U.S. poverty thresholds defined by year and family composition.

To measure the economic opportunities available in a city to men and women with particular levels of education, we use unemployment rates and employment-to-population ratios, calculated separately by city, education level (less than high school, high school, some college, four-year college degree and higher), and sex. These numbers were compiled using the Current Population Survey for the years 1998-2005, the same years covered by the Fragile Families data. These measures were based on data for adults aged 25-54 years old. We opt for unemployment and employment rates as measures of economic opportunity because they are comparable across cities that vary in their cost of living. In contrast, wage rates or median income levels are not directly comparable across cities because of wide differences in cost of living.

Unemployment rates and employment-to-population ratios measure different aspects of labor markets. Unemployment rates exclude those not in the labor market, (e.g., those enrolled in school, stay at home parents, or discouraged workers) from both the numerator and denominator. The unemployment rate is an indicator of the extent to which those actively seeking work are able to find a job. In contrast, the employment-to-population ratio is the overall employment rate including everyone in the population in the denominator. The employment-to-population ratio is a straightforward accounting of the proportion of a population that is working. Low employment-to-population ratios can result either because of high unemployment among those seeking work or because a relatively large proportion of the population is not looking for work.

Control Variables

We control for time-varying mother and father characteristics collected in each survey wave including school enrollment, age, number of children, multipartnered fertility, and time-invariant characteristics including race, religion, and growing up in a single parent household. We also control for assortative mating characteristics of couples, which may act as a barrier to marriage: whether the parents report different race/ethnic identification, markedly different ages, or different levels of religiosity. We also include city fixed effects in all our models to control for time-invariant characteristics of cities that may influence education and marriage.

Analytic Approach

We use Cox Proportional Hazards Models to predict waiting time to marriage. This modeling approach has the advantages of taking into account duration until marriage and right censoring, and allowing for time-varying covariates. Event history models are well suited to address our central question: why are mothers and fathers with lower levels of education less likely to marry following a nonmarital birth?

In Tables 3 and 4, we model the time to marriage as a function of mothers’ and fathers’ educational attainment, and examine the effect of adding explanatory variables on the relationship between educational attainment and marriage. In Table 5, we analyze the relationship between labor market conditions and the waiting time to marriage for subgroups defined by mothers and fathers’ educational attainment to examine whether the relationship between labor market conditions and marriage varies by education.

Table 3.

Predicting Waiting Time to Marriage after a Nonmarital Birth for Parent Education Groups Controlling for Individual-Level Economic Characteristics and City Fixed Effects

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | ||

| Mother less than high school (ref.) | ||

| Mother high school | 1.26 * | 1.24 * |

| Mother some college | 1.38 ** | 1.32 * |

| Mother college degree | 1.81 ** | 1.51 * |

| Father less than high school (ref.) | ||

| Father high school | 1.06 | 1.03 |

| Father some college | 1.42 ** | 1.31 * |

| Father college degree | 2.19 ** | 2.00 ** |

| Economic circumstances | ||

| Mother employed | .77 ** | |

| Father employed | 1.49 ** | |

| Mother’s income-to-poverty ratio | 1.19 ** | |

| Father’s income-to-poverty ratio | .93 ** | |

| Mother’s health is fair or poor | .80 | |

| Father’s health is fair or poor | .76 | |

| Mother drug/alcohol problem in last year | .87 | |

| Father drug/alcohol problem in last year | .83 | |

| Controls | ||

| Mother enrolled in school | .85 | .83 |

| Father enrolled in school | .84 | .84 |

| Mother is white (ref.) | ||

| Mother is black | .43 ** | .48 ** |

| Mother is Hispanic | .96 | 1.01 |

| Mother is not white, black, or Hispanic | .79 | .80 |

| Parents are not the same race/ethnicity | .78 * | .82 |

| Mother never attends religious services (ref.) | ||

| Mother attends religious services regularly | 1.65 ** | 1.64 ** |

| Mother attends religious service occasionally | 1.33 * | 1.32 * |

| Father is more religious than mother | .80 | .79 |

| Father is less religious than mother | .73 ** | .75 ** |

| Number of children in household | 1.17 ** | 1.21 ** |

| Mother’s age | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Father is older than mother by 5 years or more | 1.04 | 1.05 |

| Mother is older than father by 2 years or more | 1.09 | 1.09 |

| Mother has children with another partner | .70 ** | .72 ** |

| Father has children with another partner | .58 ** | .61 ** |

| Mother lived with both biological parents at age 15 | 1.08 | 1.05 |

| Father lived with both biological parents at age 15 | .90 | .89 |

| Person-months | 169991 | 169991 |

Notes: Hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazard models are shown. Hazard ratios for city fixed effects not shown.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 4.

Predicting Waiting Time to Marriage after a Nonmarital Birth for Parent Education Groups controlling for Labor Market Conditions by Education Group and Sex

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother less than high school (ref.) | ||||||

| Mother high school | 1.24 * | 1.26 * | 1.27 * | 1.04 | 1.26 | 1.08 |

| Mother some college | 1.32 * | 1.33 * | 1.33 * | 1.04 | 1.34 | 1.07 |

| Mother college degree | 1.51 * | 1.52 * | 1.52 * | 1.17 | 1.53 | 1.21 |

| Father less than high school (ref.) | ||||||

| Father high school | 1.03 | .94 | .87 | 1.03 | 1.03 | .88 |

| Father some college | 1.31 * | 1.15 | 1.02 | 1.31 * | 1.31 * | 1.04 |

| Father college degree | 2.00 ** | 1.72 ** | 1.41 | 2.01 ** | 2.00 ** | 1.45 |

| Male unemployment rate by education | .98 | |||||

| Male employment-to-population ratio by education | 1.02 ** | 1.02 ** | ||||

| Female unemployment rate by education | .96 ** | .97 * | ||||

| Female employment-to-population ratio by education | 1.00 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Person-months | 169991 | 169991 | 169991 | 169991 | 169991 | 169991 |

Notes: Hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazard models are shown. All models include individual-level control variables, economic characteristics, and city fixed effects, but hazard ratios for these variables are not displayed.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 5.

Predicting Waiting Time to Marriage after a Nonmarital Birth within Parent Education subgroups controlling for Labor Market Conditions

| Mothers with less than high school |

Mothers with high school only |

Mothers with some college plus |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Female unemployment rate | .960 ** | .949 * | 1.029 |

| Female employment-to-population ratio | 1.006 | 1.007 | 1.003 |

| Person-months | 59759 | 47436 | 62796 |

|

| |||

| Fathers with less than high school |

Fathers with high school only |

Fathers with some college plus |

|

|

| |||

| Male unemployment rate | .966 * | .983 | .886 ** |

| Male employment-to-population ratio | 1.030 ** | 1.016 | 1.035 ** |

| Person-months | 60873 | 64200 | 44918 |

Notes: Hazard ratios from Cox proportional hazard models are shown. Each cell represents a separate regression. All models include the individual-level control and economic circumstances variables listed in Table 1. Regressions shown in the top panel also control for father’s educational attainment and regressions in the bottom panel control for mother’s educational attainment. Hazard ratios for these variables are not displayed.

p < .05

p < .01

Diagnostic cumulative hazard plots (not presented) show that the proportionality assumption is met for the mothers’ education groups but not for the fathers’ educational groups. To address the non-proportionately of fathers’ marriage hazards by education, we interacted fathers’ education with duration. This interaction did not approach statistical significance, so following Blossfeld, Golsch and Rohwer (2007: 235-237) and Allison (1995: 154-157) we present results without the interaction term.

Our analysis begins by estimating the following Cox Proportional Hazards model:

| (1) |

where ln(hr) is the log of the ratio of the hazard rate of marriage at time t to the baseline hazard rate at time 0; t is a subscript indicating time in months, m is a subscript indicating individual-level mother data, and f is a subscript indicating individual-level father data. H indicates a high school degree only, SC is some college, C represents a college degree, and less than high school is the reference cell. X is a vector of control variables. ¥ represents fixed effects for city of residence. Our standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the city-level using the “cluster” variance-component-estimator option in Stata. The parameters of greatest interest from equation (1) are β1 through β6, which represent the hazard ratio of marriage relative to the omitted category of high school dropouts.

We compare our estimates of differences in marriage by education (β1 through β6 1 to estimates from equation 2, which controls for time-varying measures of individual-level economic circumstances:

| (2) |

where E is a vector of economic circumstances (employment, income-to-poverty ratio, health, and substance use) for mothers and fathers at time t. If the estimated hazard ratios β1 through β6 in equation (2) become closer to 1 compared with equation (1), we take this as evidence that individual-level economic circumstances help to explain differences in marriage by education.

The strategy of comparing β1 through β6 coefficients across equations (1) and (2) is based on the assumption that explanatory variables have similar effects on marriage across education groups. For example, if income is associated with marriage for all education groups and less educated parents tend to have lower income-to-poverty ratios, then controlling for the income-to-poverty ratio will narrow the estimated educational difference in marriage. In separate analyses (not shown), we included interactions between education and economic variables, which supported this analytic approach.

To test the hypothesis that labor market conditions defined by city, education, and sex explain differences in marriage by education, we compare equation (2) to equation (3):

| (3) |

where LM is a vector of labor market variables for city c, education group e, and sex s (male or female). In separate models, we control for the male unemployment rate, male employment-to-population ratio, female unemployment rate, or female employment-to-population ratio. If the estimated hazard ratios β1 through β6 in equation (3) become closer to 1 compared with equation (2), we take this as evidence that the labor market conditions one is faced with given one’s education, city, and sex help to explain differences in marriage by education net of one’s current economic circumstances.

In equation (3) the estimated relationship between each labor market indicator and marriage (δ) is a mean across education groups. Separate analyses (not shown) suggest that the relationship between labor market conditions and marriage varies by mothers’ education. In our last analyses, we estimate separate models for educational subgroups:

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

Equation 4a is estimated for three subgroups: (1) mothers with less than a high school degree, (2) mothers with a high school degree only, and (3) mothers with some college or more education, and controls for fathers’ education. Equation 4b is estimated for the same subgroups for fathers, and controls for mothers’ education. We combine the some college and college degree groups in these analyses because of small cell sizes. The coefficients of primary interest are represented by δ. Comparing δ estimates across education subgroups provides evidence whether the relationship between labor market conditions and marriage varies by education.

Results

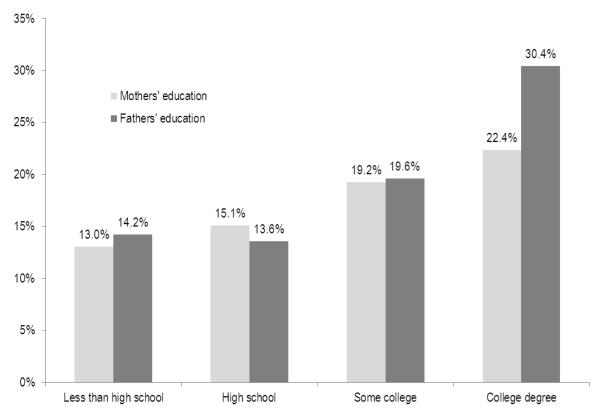

Figure 1 shows the raw differences in marriage rates at five years by mothers’ and fathers’ level of education. As shown, both mothers’ and fathers’ education are positively associated with marriage, although, for fathers, high school dropouts and those with a high school degree have similar rates of marriage.

Figure 1.

Percent of Parents who were Married 5 Years after a Nonmarital Birth by Mothers’ and Fathers’ Education at Baseline

Table 1 shows that at baseline, 40% of mothers had less than a high school degree, 34% had a high school degree or equivalent, 24% had some college, and 3% had a college degree. For fathers, 37% had less than a high school degree, 40% had a high school degree only, 19% had some college education, and 4% had a college degree. During the follow-up, 20% of mothers and 9% of fathers upgraded their education and therefore changed education categories (not shown). Mean values for our individual-level explanatory and control variables are also shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Unmarried Parents in the Fragile Families study

| % or Mean | |

|---|---|

| Married at 1-year follow-up (%) | 9.4 |

| Married at 3-year follow-up (%) | 13.7 |

| Married at 5-year follow-up (%) | 15.5 |

| Mother less than high school (%) | 39.5 |

| Mother high school (%) | 33.8 |

| Mother some college (%) | 23.7 |

| Mother college degree (%) | 3.1 |

| Father less than high school (%) | 37.1 |

| Father high school (%) | 40.4 |

| Father some college (%) | 19.0 |

| Father college degree (%) | 3.5 |

| Mother enrolled in school (%) | 18.3 |

| Father enrolled in school (%) | 15.3 |

| Mother is white (%) | 14.5 |

| Mother is black (%) | 55.5 |

| Mother is Hispanic (%) | 27.3 |

| Mother is not white, black, or Hispanic (%) | 2.7 |

| Parents are not the same race/ethnicity (%) | 15.5 |

| Mother attends religious services regularly (%) | 18.0 |

| Mother attends religious service occasionally (%) | 65.3 |

| Father is more religious than mother (%) | 29.2 |

| Father is less religious than mother (%) | 38.9 |

| Number of children in household | 1.9 |

| Mother’s age (years) | 23.9 |

| Father is older than mother by 5 years or more (%) | 28.0 |

| Mother is older than father by 2 years or more (%) | 13.3 |

| Mother has children with another partner (%) | 42.3 |

| Father has children with another partner (%) | 42.6 |

| Mother lived with both biological parents at age 15 (%) | 36.0 |

| Father lived with both biological parents at age 15 (%) | 39.1 |

| Mother employed (%) | 67.6 |

| Father employed (%) | 75.9 |

| Mother’s income-to-poverty ratio | 1.6 |

| Father’s income-to-poverty ratio | 2.2 |

| Mother’s health is fair or poor (%) | 8.4 |

| Father’s health is fair or poor (%) | 8.1 |

| Mother drug/alcohol problem in last year (%) | 3.4 |

| Father drug/alcohol problem in last year (%) | 7.1 |

| N | 3,354 |

Notes: All characteristics except married at follow-up were measured in the baseline survey.

Table 2 shows the city averages for each of our labor market indicators by education level and sex. Across the 20 cities, economic prospects improve and attachment to the labor force increases as educational attainment increases. Unemployment rates are lower and employment-to-population ratios are higher for each successive level of educational attainment for both men and women.

Table 2.

Average Labor Market Characteristics by Sex and Education Group for the Twenty Cities in the Fragile Families Study (Standard Deviations in Parenthesis)

| < High school | High school | Some college | College | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male unemployment rate | 10.0 (5.35) |

5.9 (2.27) |

3.9 (1.61) |

2.4 (1.44) |

| Male employment-to-population ratio | 70.3 (9.07) |

83.7 (4.74) |

88.0 (3.83) |

93.4 (2.66) |

| Female unemployment rate | 10.4 (4.44) |

5.0 (1.98) |

3.3 (1.30) |

2.5 (.99) |

| Female employment-to-population ratio | 50.4 (9.65) |

71.0 (5.66) |

77.3 (3.97) |

79.8 (4.01) |

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

Source: Current Population Surveys from 1998-2005

Our first set of multivariate results tests the hypothesis that individual-level economic characteristics mediate the relationship between educational attainment and marriage. Consistent with Figure 1, Table 3 shows that mothers’ and fathers’ educational attainment are positively related to marriage following a birth. Compared with mothers with less than a high school degree, mothers with a high school degree have 1.26 times the hazard of marriage, mothers with some college education have 1.38 times the hazard of marriage, and mothers with a college degree have 1.81 times the hazard of marriage (Model 1). Compared with fathers with less than a high school degree, fathers with some college education have 1.42 times the hazard of marriage, and fathers with a college degree have 2.19 times the hazard of marriage (Model 1). For fathers, high school completion is not associated with an increase in the marriage hazard relative to high school dropouts.

The second model in Table 3 shows that the addition of individual-level economic circumstances of mothers and fathers explains a small portion of the differences in marriage by education compared with Model 1. The Model 2 hazard ratios on mothers’ and fathers’ education move closer to 1, but remain statistically significant. Although some portion of the differences in marriage by education is explained by individual-level economic circumstances, the hazard of marriage remains 30 percent higher for mothers and fathers with some college and 50-100 percent higher for mothers and fathers with a college degree relative to their counterparts without a high school diploma.

Model 2 shows that mothers’ employment is negatively related to marriage, and fathers’ employment is positively related to marriage. The positive relationship between men’s employment and marriage is consistent with a large body of prior research. The negative relationship between mothers’ employment and marriage is at odds with recent research, which has suggested that mothers’ employment facilitates marriage. Our measure of the timing of changes in employment status is imprecise (imputed as the mid-point between survey waves), making the time-ordering of employment and marriage changes uncertain. Therefore, this negative relationship may in part reflect that mothers who marry are more likely to quit working than mothers who remain unmarried. Our analysis cannot distinguish between two possibilities: that mother’s employment reduces marriage or that marriage reduces mother’s employment. In separate analyses (not shown), when we assume that changes in mothers’ employment status occurred in the month before the survey in which they were reported, mothers’ employment is not significantly related to marriage. Because of the ambiguous time-ordering and the sensitivity of results to assumptions about employment timing, we recommend caution in interpreting the relationship between women’s employment and marriage.

Similar time-ordering ambiguity applies to the income-to-poverty ratios. The positive relationship between mothers’ income-to-poverty ratio and marriage could either reflect a pro-income effect of marriage for women or the ability of women with higher incomes to marry. We expect that the negative relationship between fathers’ income-to-poverty ratio and marriage results from the increase in family size associated with marriage: Because the income-to-poverty ratio takes into account family size, fathers who live apart from mothers and children may be better off by this measure than fathers in larger households. Mothers’ and fathers’ self reported fair or poor health and drug or alcohol problems have a negative but not statistically significant relationship to marriage.

Table 3 shows that individual-level economic characteristics leave a large portion of the educational difference in marriage after a birth unexplained. Table 4 considers whether city-level labor market conditions specific to one’s education level and sex can help to explain the remaining educational differences in marriage. Model 1 in Table 4 repeats the results from Model 2 in Table 3. We use this model as the benchmark to see whether local-level economic opportunities have an influence on differences in marriage by education, above and beyond their influence on individual-level economic circumstances. All models in Table 4 include individual-level control variables, individual-level economic circumstances, and city fixed effects, though the hazard ratios on these variables are omitted from tables.

Model 2 shows that taking into account the variation in male unemployment rates across cities and education groups decreases the differences in marriage by education for fathers. Compared with Model 1, the hazard ratio of marriage for the fathers with some college decreases from 1.31 to 1.15 and the hazard ratio of marriage for fathers with a college degree decreases from 2.00 to 1.72 after taking into account male unemployment rates. The relationship between the male unemployment rate and the hazard of marriage is in the expected negative direction but does not achieve statistical significance (p=.123). Model 3 follows a similar but stronger pattern: controlling for male employment-to-population ratios decreases the hazard ratio of marriage for fathers with some college from 1.31 to 1.02 and for fathers with a college degree from 2.00 to 1.41 relative to high school dropouts. The education differences in marriage for fathers are no longer statistically significant after taking into account variation in male employment rates by city and education. The hazard ratio for the employment-to-population ratio is in the expected positive direction and statistically significant.

This combination of results suggests that educational differences in male “discouraged workers” may help explain differences in marriage by education. Male employment-to-population ratios, which capture any difference in discouraged workers across education groups, are more strongly related to marriage and explain more of the difference in marriage across education groups than male unemployment rates, which do not take into account discouraged workers. The higher proportion of discouraged workers among low-educated men likely reflects persistent barriers to employment.

Models 2 and 3 show that male labor market conditions are an important element in the relationship between fathers’ education and marriage after a birth, but controlling for male labor market conditions does not affect the relationship between mothers’ educational attainment and marriage. Male labor markets have no influence on the relationship between mothers’ education and marriage because of the considerable degree of educational heterogamy in our sample. Just over half of mother and father couples share the same level of educational attainment. Furthermore, occupational segregation by gender may mean that women and men face education-specific labor markets that differ considerably. We find the correlation between male and female labor market variables is relatively low (.13 for male and female unemployment rates and .29 for male and female employment-to-population ratios) across the twenty cities in our sample.

The next set of models takes into account the variation in female labor market conditions by education level and city. Taking into account female unemployment rates in Model 4 greatly reduces differences in marriage across mothers’ education groups. Compared to Model 1, the marriage hazard ratios in Model 4 drop from 1.24 to 1.04 for high school graduates, from 1.32 to 1.04 for mothers with some college, and from 1.51 to 1.17 for mothers with a college degree compared with mothers who did not complete high school. After taking into account female unemployment rates, mothers’ differences in marriage by education are almost completely eliminated and are not statistically significant. As expected, female unemployment rates are negatively related to marriage. Model 4 is consistent with the hypothesis that women with lower educational attainment are less likely to marry compared with their higher educated counterparts, because they face worse economic prospects.

In Model 5, we take into account the variation in female employment-to-population ratios across cities and education groups. Unlike female unemployment rates, female employment-to-population ratios do not help to explain differences in marriage by mothers’ education level. The female employment-to-population ratio is also not related to marriage after a birth.1 The employment-to-population ratios will be lower when women are not in the labor force; therefore, some of the variation in female employment-to-population ratios across city and education groups reflects variation in the proportion of women who are stay-at-home mothers. In contrast, the unemployment rate is a reflection of those without employment among those who are in the labor force (either as employed persons or job-seekers). Combining the Model 4 and 5 results suggests that the ability of women to find employment when they seek it affects educational differences in marriage but that women’s decision to be in or out of the labor force does not.

The final model in Table 4 controls for male employment-to-population ratios and female unemployment rates, which demonstrated the most explanatory power in previous models. Taking into account these education-specific labor market indicators explains most of the educational differences in marriage. In this model, the mother and father education groups are statistically indistinguishable in their hazard of marriage; although, the difference between fathers with a college education and fathers with less than a high school degree approaches statistical significance (hazard ratio of 1.45 and p=.051). In Model 6, female unemployment rates are significantly and negatively related to marriage and male employment rates are significantly and positively related to marriage as expected.

As a robustness check (not shown), we use logistic regression models to estimate the predicted probability of marriage at five years after the baseline interview for particular education groups with labor market indicators fixed at particular values. For example, we estimate the predicted probability of marriage for high school dropouts with female unemployment rates fixed at the mean for high school dropouts then compare this to the predicted probability of marriage for high school dropouts when the female unemployment rate is fixed at the mean for college graduates. We do the same for the male employment-to-population ratio. These exercises demonstrate that educational differences in marriage would largely disappear if labor market conditions for different education groups were equalized.

Next we turn to the question of whether the relationship between labor market conditions and marriage varies by education group. As shown in Table 5, unemployment is negatively associated with marriage for mothers in the less than high school and high school only groups. This is consistent with the theory that the marriage-promoting “income effect” dominates among lower educated mothers. In contrast, the relationship between unemployment and marriage is not statistically significant (and has the opposite sign) for mothers in the some college and above group. For mothers with some college and above, unemployment is not associated with marriage. The female employment-to-population ratio is not related to marriage, echoing the earlier finding that the ability for female job seekers to find employment influences marriage, but the decision to be in or out of the labor force does not.

For fathers, Table 5 shows that better male labor market conditions are positively related to marriage for all educational groups, whether measured by lower unemployment rates or higher employment-to-population ratios. These relationships are significant for those with less than a high school degree and some college plus and in the same direction but not statistically significant for those with a high school degree. This is consistent with a large body of prior research showing a robust positive relationship between men’s economic circumstances and marriage (Burstein 2007).

In summary, our results suggest the following: (1) Strong male labor markets encourage marriage for fathers at all levels of education; (2) Strong female labor markets encourage marriage for low educated mothers and have little or no effect on marriage for more highly educated mothers; and (3) Low-educated mothers and fathers are less likely to marry after a nonmarital birth, because their labor market opportunities are more limited compared with more highly-educated parents.

Discussion

In our paper, we examine why higher levels of educational attainment are associated with marriage. We combine survey information from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study with local labor market measures from the Current Population Survey to see whether differences in current economic circumstances and education-specific labor market conditions can help explain differences in marriage by education. We focus on unmarried parents, a subpopulation of particular interest because their marriage decisions will influence the settings in which young children are raised.

In our sample of unmarried parents, both mothers’ and fathers’ education are associated with transitions to marriage. These differences in marriage by education narrow only slightly after taking into account mothers’ and fathers’ current economic circumstances. However, these educational differences in marriage largely disappear after we control for education-specific labor market conditions. Our results suggest that marriage rates for fathers with less than a high school education, a high school degree, some college, or a college degree would be similar if their economic opportunities were equivalent. Likewise, marriage rates for mothers with varying levels of education would be similar if their economic opportunities were equivalent.

How do labor market conditions influence marriage and explain educational differences? Labor market conditions improve markedly as one’s educational attainment increases. We propose that poor labor markets delay or impede marriage because of their effects on economic circumstances, occupational mobility, and perceptions of job security and future opportunity. These economic influences have direct effects on marriage timing because of well-documented and rigid economic pre-requisites for marriage, such as setting up a household, paying for a wedding, and feeling economically secure (Gibson-Davis, Edin and McLanahan 2005; Smock, Manning and Porter 2005). These economic influences are also likely to affect marriage indirectly because economic insufficiency and insecurity are a common source of relationship conflict.

Prior research on the Great Depression and the Iowa Farm Crisis, as well as contemporary research linking economic circumstances and opportunities to marriage timing, provide evidence in support of economic pathways linking labor market conditions to marriage (Conger and Elder 1994; Conger et al. 1990; Lichter, McLaughlin and Ribar 2002; Blau, Kahn and Waldfogel 2000). This prior research focused on how male unemployment and economic opportunities affect overall rates of marriage and divorce. We extend this earlier literature by showing that labor market conditions lead to educational stratification in marriage. We also show that women’s economic opportunities are as important for marriage as men’s.

Our paper contributes to the debate about women’s earning power and marriage. The literature tends to interpret positive relationships between women’s economic opportunities and marriage as evidence that an “income effect” dominates, and a negative relationship as support for the “independence effect.” We propose that the income effect may dominate in some contexts or for some subgroups of women and the independence effect may dominate in other settings and other subgroups. We demonstrate this by showing that better labor markets are positively associated with marriage only for mothers with a high school degree or less. We hypothesize that the marriage promoting “income effect” dominates among mothers with low education, but not their more educated counterparts. For more educated mothers, labor market conditions are not significantly related to marriage. Future research can test whether these results are unique to unmarried mothers or hold true for women more generally.

Three limitations in the present analysis are worth discussing. First, our study focuses on marriage following a nonmarital birth, and the results may or may not be generalizable to educational differences in marriage more generally. However, our focus on unmarried parents enabled us to incorporate characteristics of both members of a couple into our analysis, something that prior research has typically not been able to do. In separate analyses, we find that omitting data on fathers’ education and substituting the male labor market conditions that correspond to mothers’ level of education (as one would be forced to do in the absence of couple data) would have led to the errant conclusion that fathers’ labor market conditions do not affect marriage after a nonmarital birth. A further rationale for our focus on unmarried couples is the fact that almost 40% of recent births were to unmarried parents, making this group of unmarried parents and their children a sizable and growing proportion of all families.

Second, any study that observes families after some family-formation decisions have already been made will face issues of sample selection. At the time our sample began to be observed, the 3,354 couples had already decided to carry a pregnancy to term without getting married. We recognize that educational attainment and economic conditions prior to our observation period may have influenced these decisions. However, our underlying theoretical model predicts that low education and poor economic conditions will lead to more nonmarital births and less marriage after a birth. We have no reason to think that the influence of education and economic conditions on marriage would manifest before a birth and then have no effect on marriage after a nonmarital birth.

Third, we lacked precise information on the time-ordering of our individual-level measures of economic circumstances; and, therefore, could not distinguish the time-ordering in the relationship between mother and father’s current economic circumstances and marriage. Even if we were able to establish time-ordering, the causal ordering in the relationship between economic circumstances and marriage would remain ambiguous because individuals may change their behaviors in anticipation of and preparation for marriage. The challenge of establishing the causal direction between individual-level economic circumstances and marriage is one rationale for focusing on the influence of labor market conditions on marriage. Labor market conditions are not affected by an individual’s marital status or marriage plans but do have a large influence marriage decisions in our analyses. An alternative to our approach and a direction for future research is to directly measure the mechanisms through which labor markets affect marriage. Direct measures of individuals’ feelings of economic security; upward or downward mobility; and anticipated economic circumstances in the future could be tested as predictors of marriage and as explanations for educational stratification in marriage. Surveys could also build on qualitative research to craft pointed questions about economic pre-requisites for marriage.

In the longstanding tradition of sociological research linking macro-environments to personal decisions, our paper shows that labor market contexts have an important influence on marriage timing. This finding has particular relevance in the context of the current economic recession. Taken together, our findings suggest that the current economic recession is likely to delay marriage and to widen educational disparities in marriage. Our analysis covers the period from 1998 to 2006 and pre-dates the recession that began in 2008. Our results suggest that the economic downturn, which has doubled the unemployment rate at all levels of education, will delay marriage for most unmarried mothers and fathers, but especially for mothers and fathers with lower levels of education. When the next round of data from the Fragile Families study becomes available, these predictions about the influence of the recession on marriage and on educational stratification in marriage can be tested.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge suggestions from Paul Allison, Audrey Beck, Francesco Billari, Marcy Carlson, Jerry Jacobs, Hugh Louch, Steve Martin, and Tod Mijanovich, and editorial assistance from Faizan Khan. Funding for the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study was provided by NICHD (#R01HD36916) and a consortium of private foundations and other government agencies.

Footnotes

Although the magnitude of the hazard ratios on education do not change in Model 5 compared with Model 1, the standard errors increase when female employment-to-population ratios are added to the model, leading to a loss of statistical significance. The increase in standard errors comes about because employment rates are strongly correlated with maternal education but not with waiting time to marriage.

Contributor Information

Kristen Harknett, University of Pennsylvania.

Arielle Kuperberg, University of North Carolina, Greensboro.

References

- Allison Paul. Survival Analysis Using SAS: A Practical Guide. SAS Institute, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Elijah. Streetwise: Race, Class, and Change in an Urban Community. University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ashenfelter Orley, Krueger Alan. Estimates of the Economic Return to Schooling from a New Sample of Twins. The American Economic Review. 1994;84(5):1157–73. [Google Scholar]

- Blau Francine D., Lawrence M. Kahn, Waldfogel Jane. Understanding Young Women’s Marriage Decisions: The Role of Labor and Marriage Market Conditions. Industrial and Labor Relations Review. 2000;53(4):624–47. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld Hans-Peter, Katrin Golsch, Rohwer Götz. Event History Analysis With Stata. Lawrence Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Susan L. Family Structure and Child Well-Being: The Significance of Parental Cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(2):351–67. [Google Scholar]

- Burstein Nancy R. Economic Influences on Marriage and Divorce. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2007;26(2):387–429. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., Corcoran Mary E. Family Structure and Children’s Behavioral and Cognitive Outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(3):779–92. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., Sara McLanahan, England Paula. Union Formation in Fragile Families. Demography. 2004;41(2):237–61. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh Shannon E., Huston Aletha C. Family Instability and Children’s Early Problem Behavior. Social Forces. 2006;85(1):551–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew. Marriage, Divorce and Remarriage. Harvard University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James. Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Conger Rand D., Elder Glen H., Jr . Families in Troubled Times: Adapting to Change in Rural America. Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Conger Rand D., Elder Glen H., Jr., Lorenz Frederick O., Conger Katherine J., Simons Ronald, Whitbeck Les B., Huck Shirley, Melby Janet N. Linking Economic Hardship to Marital Quality and Instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(3):643–56. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan Greg J., Wilkerson Bessie, England Paula. Cleaning Up Their Act: The Effects of Marriage and Cohabitation on Licit and Illicit Drug Use. Demography. 2006;43(4):691–710. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Emile. Suicide. The Free Press; 1997. [1897] [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn, Kefalas Maria J. Promises I Can Keep: Why Poor Women Put Motherhood Before Marriage. University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edin Kathryn. How Low-Income Single Mothers Talk About Marriage. Social Problems. 2000;47(1):112–33. [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen. Children of the Great Depression: Social Change in Life Experience. University of Chicago Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ellwood David, Jencks Christopher. The Spread of Single-Parent Families in the United States Since 1960. In: Moynihan Daniel P., Smeeding Timothy M., Rainwater Lee., editors. The Future of the Family. Russell Sage; 2004. pp. 25–65. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle Barbara. Putting People into Place. Demography. 2007;44(4):687–703. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby Paula, Cherlin Andrew J. Family Instability and Child Well-Being. American Sociological Review. 2007;72(2):181–204. doi: 10.1177/000312240707200203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg Frank F. The Making of the Black Family: Race and Class in Qualitative Studies in the Twentieth Century. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:429–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines Anna, Yoshikawa Hiro. Five Year Effects of an Antipoverty Program on Marriage Among Never Married Mothers. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2006;25(1):11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis Christina, Kathryn Edin, McLanahan Sara. High Hopes, but Even Higher Expectations: The Retreat From Marriage Among Low-Income Couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(5):1301–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein Joshua R., Kenney Catherine T. Marriage Delayed or Marriage Forgone? New Cohort Forecasts of First Marriage for U.S. Women. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(4):506–19. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag Marcia, Secord Paul F. Too Many Women? The Sex Ratio Question. Sage Publications; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan Michael T., Tuma Nancy B., Groeneveld Lyle P. Income and Marital Events: Evidence from an Income-Maintenance Experiment. The American Journal of Sociology. 1977;82(6):1186–1211. [Google Scholar]

- Harknett Kristen, Gennetian Lisa A. How an Earnings Supplement Can Affect Union Formation Among Low-Income Single Mothers. Demography. 2003;40(3):451–78. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson William H., Skinner Jonathan. Labor Supply and Marital Separation. American Economic Review. 1986;76(3):455–69. [Google Scholar]

- Komarovsky Mirra. The Unemployed Man and His Family. Dryden; 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T., McLaughlin Diane K., Ribar David C. Economic Restructuring and the Retreat from Marriage. Social Science Research. 2002;31(2):230–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lillard Lee A., Panis Constantijn W.A. Marital Status and Mortality: The Role of Health. Demography. 1996;33(3):313–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liming Drew, Wolf Michael. Occupational Outlook Quarterly. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2008. Job Outlook by Education 2006-16. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg Shelley, Pollak Robert A. American Family and Family Economics. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2007;21(2):3–26. doi: 10.1257/jep.30.2.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D., Lamb Kathleen A. Adolescent Well-Being in Cohabiting, Married, and Single-Parent Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(4):876–93. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara, Sandefur Gary. Growing up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara. Diverging Destinies: How Children are Faring Under the Second Demographic Transition. Demography. 2004;41(4):607–27. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara, Percheski Christine. Family Structure and the Reproduction of Inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:257–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ogburn William F., Nimkoff Meyer F. Technology and the Changing Family. Greenwood Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Ogburn William F., Thomas Dorothy S. The Influence of the Business Cycle on Certain Social Conditions. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1922;18(139):324–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ono Hiromi. Women’s Economic Standing, Marriage Timing, and Cross-National Contexts of Gender. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65(2):275–86. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer Valerie. A Theory of Marriage Timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(3):563–91. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne Cynthia, Sara McLanahan. Partnership Instability and Child Well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(4):1065–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers Stacey J. Wives’ Income and Marital Quality: Are There Reciprocal Effects? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(1):123–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J., Groves W. Byron. Community Structure and Crime: Testing Social-Disorganization Theory. American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94(4):774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Schoen Robert, Cheng Yen-Hsin A. Partner Choice and the Differential Retreat From Marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Smock Pamela J., Manning Wendy D. Cohabiting Partner’s Economic Circumstances and Marriage. Demography. 1997;34(3):331–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock Pamela J., Manning Wendy D., Porter Meredith. ’Everything’s There Except Money’: How Money Shapes Decisions to Marry Among Cohabiters. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(3):680–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney Megan. Two Decades of Family Change: The Shifting Economic Foundations of Marriage. American Sociological Review. 2002;67(1):132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney Megan, Cancian Maria. The Changing Importance of White Women’s Economic Prospects for Assortative Mating. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(4):1015–28. [Google Scholar]

- Testa Mark, Astone Nan Marie, Krogh Marilyn, Neckerman Kathryn M. Employment and Marriage among Inner-City Fathers. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1989;501:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Arland, Young-DeMarco Linda. Four Decades of Trends in Attitudes Toward Family Issues in the United States: The 1960s through the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(4):1009–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Ventura Stephanie J. Changing Patterns of Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff Patricia. Economic Distress and Family Relations: A Review of the Eighties. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(4):1099–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. Does Marriage Matter? Demography. 1995;32(4):483–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Lynn, Rogers Stacey J. Economic Circumstances and Family Outcomes: A Review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62(4):1035–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William Julius. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Yu, Raymo James M., Goyette Kimberly, Thornton Arland. Economic Potential and Entry Into Marriage and Cohabitation. Demography. 2003;40(2):351–67. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavodny Madeline. Do Men’s Characteristics Affect Whether a Nonmarital Pregnancy Results in Marriage? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(3):764–73. [Google Scholar]