Abstract

Background

Gene duplication and subsequent functional divergence especially expression divergence have been widely considered as main sources for evolutionary innovations. Many studies evidenced that genetic regulatory network evolved rapidly shortly after gene duplication, thus leading to accelerated expression divergence and diversification. However, little is known whether epigenetic factors have mediated the evolution of expression regulation since gene duplication. In this study, we conducted detailed analyses on yeast histone modification (HM), the major epigenetics type in this organism, as well as other available functional genomics data to address this issue.

Results

Duplicate genes, on average, share more common HM-code patterns than random singleton pairs in their promoters and open reading frames (ORF). Though HM-code divergence between duplicates in both promoter and ORF regions increase with their sequence divergence, the HM-code in ORF region evolves slower than that in promoter region, probably owing to the functional constraints imposed on protein sequences. After excluding the confounding effect of sequence divergence (or evolutionary time), we found the evidence supporting the notion that in yeast, the HM-code may co-evolve with cis- and trans-regulatory factors. Moreover, we observed that deletion of some yeast HM-related enzymes increases the expression divergence between duplicate genes, yet the effect is lower than the case of transcription factor (TF) deletion or environmental stresses.

Conclusions

Our analyses demonstrate that after gene duplication, yeast histone modification profile between duplicates diverged with evolutionary time, similar to genetic regulatory elements. Moreover, we found the evidence of the co-evolution between genetic and epigenetic elements since gene duplication, together contributing to the expression divergence between duplicate genes.

Keywords: Histone modification, Histone modification code divergence, Gene duplication, Expression divergence, Epigenetic divergence, cis-regulation, trans-regulation

Background

Although gene duplication has been widely considered as the main source of evolutionary novelties [1-4], the issue of duplicate gene preservation remains a subject of hot debate, i.e., how duplicate copies can escape from being pseudogenized and then evolve from an initial state of complete redundancy to a steady-stable state that both functionally divergent copies are maintained by purifying selection. As one of plausible hypotheses, rapid expression divergence between duplicate genes may be the first step that is fundamental for the preservation of redundant duplicates [3]. There are three recognized types involved in expression regulatory mechanism: (i) cis-regulation of transcription mediated by promoters, enhancers, silencers, etc.; (ii) trans-regulation mediated by regulatory proteins binding to cis elements, such as transcription factors (TF); and (iii) epigenetic regulation, such as DNA methylation, specific histone modification pattern of genes (histone code hypothesis). Many studies have addressed the effect of cis- and trans- regulatory mechanisms on the expression divergence after gene duplication, e.g., cis-regulatory motif, TF-binding interaction, trans-acting expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) [5-10]. Though there is increasing evidence that epigenetic changes may play important roles in the initial expression divergence between duplicate genes [11-15], little study has been done about how regulatory network between duplicate genes evolve at epigenetic level.

Epigenetic regulation on gene expression is a highly complex process. In a broad sense, it includes DNA methylation, histone modification, nucleosome occupancy, as well as microRNA [11]. Moreover, these epigenetic elements can interact with each other, for instance, the reciprocity between DNA methylation and histone modification [16,17]. The complexity of epigenetic regulation has made it difficult to explore its role in regulatory divergence between duplicates. Nevertheless, we have recognized budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) as an ideal organism for our purpose, because its epigenetic regulation is relatively simple: DNA cytosine methylation and microRNA were not detected [18,19]. In other words, histone modification is the main representation for epigenetic modification in the budding yeast, less affected by other epigenetic modification types. Therefore, in the present study, we focus on the evolution of histone modification (HM) between yeast duplicate genes.

Eukaryotic DNA with a unit of 146 bp wound around a histone octamer (two copies of each core histone H2A, H2B, H3, H4) is assembled into chromatin. Histone N-terminal tails are subject to multiple covalent post-translational modifications, including lysine (K) acetylation, lysine or arginine (R) methylation, serine (S) phosphorylation, and so on [20,21]. Enormous possible combinations and interactions of histone modification types constitute histone code. The ‘histone code’ hypothesis claims that a specific pattern of hisone modification code can produce a specific effect on local chromatin structure, modulating DNA accessibility, and consequently regulating transcription and other DNA-based biological processes [20-24].

Our goal is to investigate the pattern of yeast histone modification (HM) code divergence between duplicates. Our hypothesis claims (i) that, when a gene is duplicated, the gene-specific histone modification profile is also duplicated, so on average duplicate pairs tend to have a higher degree of HM code similarity than randomly selected singleton gene pairs; and (ii) that since duplication, HM-code profile between duplicate copies become divergent with evolutionary time. We test these two predictions by conducting genome-wide analyses, as well as genes involved in different biological functions. Moreover, we are particularly interested in whether genetic regulatory elements, including cis-motifs (such as TATA box) and transcription factors, and epigenetic HM-code profile co-diverge during the evolution since gene duplication. To this end, time-dependent confounding factors in both genetic and epigenetic factors need to be ruled out. Finally, the significance of our study for having a better understanding of regulatory evolution after gene duplication is discussed.

Results

Combinational interactions of histone-modifying enzymes (HATs, HDACs, HMTs, HDMs, etc.) to histone N-tail produce numerous types of post-translational modification of histones (H2A, H2B, H3, H4), such as methylation, acetylation [25]. Moreover, the same modification site can be affected by different modifying enzymes, and vice versa, generating different histone modification combinations, like H3K4me2 and H3K4ac (dimethylation and acetylation in Lys4 of histone H3, respectively), or H4K8ac (acetylation in Lys8 of histone H4). In this study, histone modification (HM) code of a gene represents the combined profile of different HM sites, HM types and HM states in gene promoter and open reading frame (ORF) regions, respectively (see Methods). We believe that the HM code of a gene reveals the pattern of HM mediated regulatory network of that gene.

Functional redundancy in histone modification (HM) between yeast duplicate genes

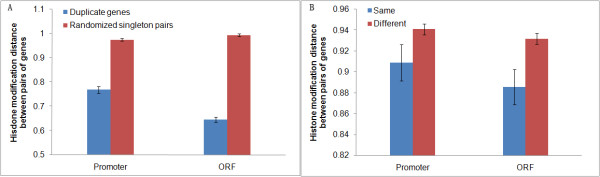

Because of evolutionary relatedness, duplicate pairs may have a higher similarity of histone modification (HM) code than two randomly selected single-copy genes (singletons). To test this hypothesis, we compared the distance of HM code between duplicate pair and randomized singleton pair. To be simple we choose one minus Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient, i.e., DHM = 1-r, to define the distance of HM code. The larger the value of DHM, the higher divergence of histone modification code between duplicate genes. Specifically, denote the distance of HM code associated in promoter and ORF regions by DHM-P and DHM-O, respectively. Randomized pairs were selected from single copy genes with 10000 repeats. As expected, we observed that both DHM-P and DHM-O measures show a lower divergence degree of histone modification code between duplicate genes than that of randomized singleton pairs (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P < 10-15 for both cases; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the histone modification divergence between yeast genes. Comparison of the histone modification divergence between (A) duplicate genes and randomized pairs of single-copy genes, and (B) all pairs of genes in the same and different chromosomes.

Generally speaking, local chromatin environment around genes is one of important components leading to different histone modification code of each gene. While chromatin environment differs in different chromosomes, duplicate genes locating in different chromosomes may be under different chromatin environment, possessing the chromosome-specific HM profile. Following this argument, we classified all yeast gene pairs (duplicate and randomized singleton pairs) under study into two groups: they are located in the same chromosome, or different chromosomes, and tested the relationship between histone modification pattern and chromosome condition. We observed that though the HM profile divergence is not significantly correlated with location distance of gene pairs in the same chromosome (Pearson’s product-moment correlation: r = 0.06, P = 0.09 for promoter region and r = 0.02, P = 0.45 for ORF region), gene pairs locating in the same chromosome share more common HM code than that in different chromosomes (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P = 0.07 and P = 0.01 for promoter and ORF regions, respectively; Figure 1B).

The chromosome effect on the HM-code divergence between duplicate genes may suggest an alternative interpretation about a higher similarity of HM distance between duplicate genes than random pairs. That is, duplicate pairs tend to be located in the same chromosome because of tandem gene duplications, compared to randomized singleton pairs (Chi-squared test: χ2=17.2, d.f. = 1, P < 10-4). To rule out this possibility, we chose duplicate pairs and randomized singleton pairs where both copies are belonging to different chromosomes, and observed the similar result to Figure 1A (see Additional file 1: Figure S1). Hence, we conclude that duplicate genes represent their functional redundancy at the level of histone modification mediated regulatory network.

The evolution of HM is coupled with coding sequence divergence after gene duplication

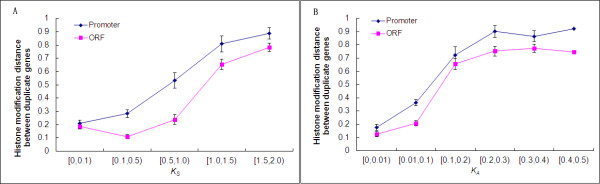

We further expect that functional redundancy in histone modification code of duplicate genes as shown in Figure 1A would maintain a high degree in recently duplicated genes, and low in ancient duplicates. To verify this claim, we investigated the relationship between the distance of HM code (DHM-P or DHM-O) and coding sequence divergence (the synonymous distance KS or the nonsynonymous distance KA between duplicate genes). Considering the statistically unreliable estimation of synonymous or nonsynonymous substitution distance when KS or KA becomes larger because of repeated substitutions at the same site, we selected duplicate pairs with KS < 2.0 and KA < 0.5 for this analysis. We observed that both DHM-P and DHM-O are positively correlated with KS or KA (Pearson’s product-moment correlation: all r > 0.45, P < 10-15 for all data points; Figure 2), suggesting that the divergence of HM code is coupled with the coding sequence divergence between duplicate genes. To avoid correlated data points bringing the bias, we selected independent pairs of duplicate genes using the method from Zou et al. [9] and reanalyzed. The similar result remains hold (all r > 0.40, P < 10-13 for all data points; in Additional file 1: Figure S2).

Figure 2.

The divergence of histone modification pattern between duplicate genes (DHM-P, DHM-O) increases with synonymous distance KS (panel A) or nonsynonymous distance KA (panel B) of duplicate genes..

Considering KS or KA as a proxy to evolutionary time since gene duplication, we suggest that the correlation between the HM-code divergence and the coding sequence divergence has been mainly driven by mutations accumulated with evolutionary time. Our interpretation is based on two reasons: First, we observed a weak negative correlation between the HM divergence and the KA/KS ratio of duplicate genes (Pearson’s product-moment correlation: r = -0.12, P < 10-7 for DHM-P and r = -0.05, P = 0.04 for DHM-O). As the KA/KS ratio is an indicator of sequence conservation in coding region, our finding implies that duplicate genes with stringent functional constraints on coding sequence may have greater divergence in the HM code, but the effect is marginal. Second, promoter HM code of duplicate genes diverges much quicker than that of ORF HM code (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P < 10-11; Figure 2), while significant but weak difference of DHM-P and DHM-O in randomized singleton pairs (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P = 0.02; Figure 1). Some factors may be involved to accelerate the divergence of promoter HM code between duplicate genes, such as the evolution of transcription factors (TF) shared by duplicate genes.

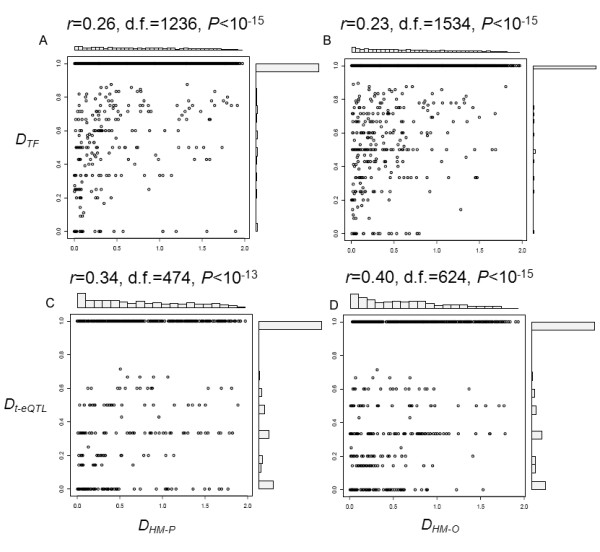

Co-evolution of the HM-code divergence between duplicates with several genetic regulatory elements

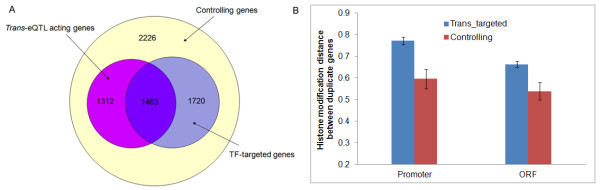

The interaction between epigenetic and genetic elements in gene regulation has been increasingly acknowledged [21,26], raising an interesting question whether the divergence of histone modification code between duplicate genes co-evolves with some trans-acting factors binding to those duplicate genes. We first studied the relationship between the distance of promoter HM code (DHM-P) and the distance of transcription factors (DTF) and trans-acting expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) (Dt-eQTL) between duplicate genes. Trans-acting eQTLs of one gene represent all trans-regulatory proteins for its transcription, not limited to transcription factors. Two distance measures DTF and Dt-eQTL were determined by Czekanowski-Dice formula (Methods). We found that they are significantly correlated (Peasron’s product-moment correlation: r > 0.25, P < 10-13; Figure 3A 3C). Similar results were obtained in the case of ORF HM code (Figure 3B 3D).

Figure 3.

Relationship between the distance of histone modification pattern and trans-regulators shared by duplicate genes. (A) and (B) show the correlation between the distance of transcription factors shared by duplicate genes and the divergence of promoter and ORF histone modification pattern between duplicate genes, respectively, while (C) and (D) represent the interrelationship between the distance of trans-acting eQTLs targeted to the duplicate genes and the distance of promoter and ORF histone modification pattern between duplicate genes, respectively.

As both DHM-P and DHM-O, as well as Dt-eQTL and DTF, increase with evolutionary time (KS or KA as the proxy) [Figure 2; 9], it is reasonable to suspect that KS or KA may underlie these statistically significant correlations between the HM code and genetic regulatory elements. We conducted the partial correlation in DHM-P-DTF and DHM-P-Dt-eQTL of duplicate genes under the controlling of KS and KA variables (with the restriction of KS < 2.0 and KA < 0.5), and still observed the significant relationship (r = 0.18, P < 0.001 for DHM-P-DTF and r = 0.15, P < 0.05 for DHM-P-Dt-eQTL), though they are relatively weak. In short, our analysis provides the evidence that the histone modification code and trans-regulators shared by duplicate genes may have co-evolved since gene duplication.

Moreover, we design the following analysis to further explore the co-evolution between the HM code and trans-regulators (TF or trans-acting eQTL), by dividing yeast genes into two categories, trans-targeted genes and controlling genes. Trans-targeted genes are genes that are targeted by transcription factors (TF-targeted genes) or have at least one trans-acting eQTL (trans-eQTL acting genes) and the rest of genes are controlling genes (Methods). We totally obtained 4495 trans-targeted genes and 2226 controlling genes (Figure 4A). Interestingly, both promoter and ORF HM code distances of duplicates in the group of trans-targeted genes are, on average, significantly higher than those in the group of controlling genes (Figure 4B) (Wilcoxon rank sum test: promoter, P = 0.003 and ORF, P = 0.0001). It should be noticed that the pattern we observed in Figure 4B would not be affected by the strong correlation between the HM divergence and evolutionary time (KS as the proxy) of duplicate genes, because the distribution of KS has been found no significant difference between trans-targeted genes and controlling genes (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P = 0.08).

Figure 4.

Different evolutionary rate of the histone modification code for duplicate genes in trans-targeted genes and controlling genes. (A) The information of different category genes, trans-targeted genes (TF-targeted genes and trans-eQTL acting genes) and controlling genes; (B) Comparison of the promoter histone modification distance (DHM-P) and the ORF histone modification distance (DHM-O) of duplicate genes between trans-targeted genes and controlling genes. Here, trans-targeted genes are the union of TF-targeted genes and trans-eQTL acting genes.

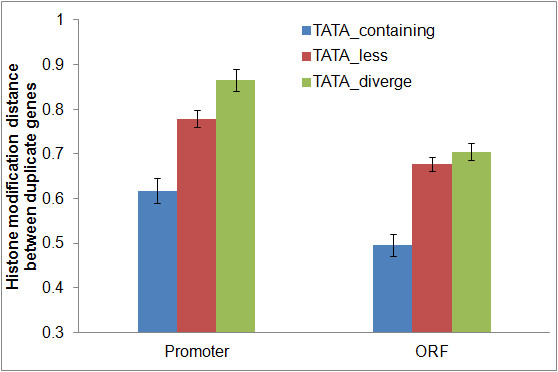

The HM-code divergence and TATA-box regulation

TATA box is the core promoter element for gene regulation responding to environmental stresses [27,28]. To examine the role of TATA box in the HM-code divergence between duplicate genes, we divided all yeast duplicate pairs into three groups, TATA-containing (both have TATA-box), TATA-less (both do not have TATA-box), and TATA_diverge (only one copy has TATA-box). We compared the HM-code distance in promoter (DHM-P) and ORF (DHM-O) region between duplicate genes in these groups. Interestingly, both DHM-P and DHM-O show the highest degree in the TATA-diverge group, and the lowest in the TATA-containing group (Figure 5) (Wilcoxon rank sum test: promoter, P < 10-10; ORF, P < 10-15).

Figure 5.

The evolution of promoter or ORF histone modification pattern of duplicate genes which have different status of TATA box.

Our explanation is as follows. Note that TATA-containing genes may interact with some specific chromatin modification factors to regulate gene expression [29]. In the TATA_diverge group, only one duplicate with TATA-box has such interaction, resulting in a higher HM-code divergence between them. By contrast, in the case of TATA-containing group, both duplicates with TATA-box have similar interactions, resulting in a higher HM-code similarity between them.

Biological functions and the HM-code divergence between duplicate genes

Do different biological functions affect the level of the HM-code divergence between duplicate genes? We used GO (Gene Ontology) Slim (biological process with 37 categories; see Methods) to address the issue. We analyzed DHM-P and DHM-O of duplicate genes in each GO category and compared DHM-P and DHM-O among these GO groups by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Our finding is that duplicate pairs with different biological processes differ significantly in DHM-P and DHM-O (P < 10-13 for DHM-P , P < 10-15 for DHM-O; Table 1). Use DHM-P for an example, duplicate genes involved in cofactor metabolic process, cellular amino acid and derivative metabolic process, cell cycle and cytoskeleton organization may have greater HM-code divergence, i.e., a higher DHM-P , while duplicate genes involved in translation, DNA metabolic process, pseudohyphal growth and transcription may have lower divergence of the promoter HM code. Moreover, we conducted a similar analysis on 24 cellular components (GO Slim classification, see Methods), and observed that duplicate genes in different subcellular localization also undergo the different evolutionary rate of histone modification code after gene duplication (Table 2). It is possible that duplicate genes in some biological processes or subcellular localization are young (measured by small KS) while others are old (with high KS). Since DHM-P and DHM-O are positively correlated with KS (Figure 2), we have to remove the confounding effect caused by KS. We used the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) (DHM-P or DHM-O ~ KS + T (biological process or subcellular localization) + KS:T) and the result remains statistically highly significant (Table 1, 2), suggesting KS is not a confounding factor that may affect our analyses.

Table 1.

The divergence of histone modification code associated with promoter or ORF region of duplicate genes involving in 37 biological processes

| Biological Process |

DHM-P |

DHM-O |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.E.a | Mean | S.E. | |

| Cofactor metabolic process |

1.089857 |

0.099487 |

0.94615 |

0.079585 |

| Cellular amino acid and derivative metabolic process |

1.056124 |

0.075125 |

0.735075 |

0.058636 |

| Cell cycle |

1.022464 |

0.070499 |

0.628888 |

0.045862 |

| Cytoskeleton organization |

1.011731 |

0.100702 |

0.732692 |

0.068568 |

| Carbohydrate metabolic process |

0.957513 |

0.041359 |

0.801785 |

0.03478 |

| Cell wall organization |

0.943616 |

0.078784 |

0.919398 |

0.069325 |

| Membrane organization |

0.943309 |

0.067702 |

0.786555 |

0.069908 |

| Lipid metabolic process |

0.93571 |

0.079815 |

0.731593 |

0.059279 |

| Generation of precursor metabolites and energy |

0.928247 |

0.096518 |

0.882262 |

0.072135 |

| Anatomical structure morphogenesis |

0.921051 |

0.079036 |

0.777731 |

0.073299 |

| Protein modification process |

0.900252 |

0.038873 |

0.854947 |

0.030103 |

| Protein folding |

0.895056 |

0.060764 |

0.677196 |

0.05632 |

| Response to stress |

0.891941 |

0.051014 |

0.766131 |

0.04367 |

| Protein catabolic process |

0.877025 |

0.072138 |

0.74283 |

0.065929 |

| Vesicle-mediated transport |

0.867052 |

0.045818 |

0.763747 |

0.04406 |

| Cytokinesis |

0.855475 |

0.128721 |

0.458555 |

0.075571 |

| Vitamin metabolic process |

0.844587 |

0.123271 |

0.697339 |

0.095067 |

| Transport |

0.819455 |

0.026288 |

0.726211 |

0.021028 |

| Heterocycle metabolic process |

0.812252 |

0.080271 |

0.737343 |

0.070763 |

| Meiosis |

0.803064 |

0.204095 |

0.586892 |

0.16534 |

| Cell budding |

0.798157 |

0.088983 |

0.814543 |

0.12039 |

| Signal transduction |

0.796985 |

0.069456 |

0.846847 |

0.05721 |

| RNA metabolic process |

0.792216 |

0.043033 |

0.562501 |

0.032646 |

| Cellular aromatic compound metabolic process |

0.783433 |

0.116406 |

0.685336 |

0.092675 |

| Ribosome biogenesis |

0.745581 |

0.078664 |

0.489313 |

0.057953 |

| Cellular respiration |

0.741278 |

0.175087 |

0.970903 |

0.130576 |

| Conjugation |

0.741105 |

0.115964 |

0.561448 |

0.065045 |

| Cellular homeostasis |

0.732899 |

0.107582 |

0.622864 |

0.080052 |

| Sporulation resulting in formation of a cellular spore |

0.726966 |

0.119265 |

0.430464 |

0.083954 |

| Organelle organization |

0.709827 |

0.043332 |

0.569849 |

0.029456 |

| Response to chemical stimulus |

0.675718 |

0.055068 |

0.590837 |

0.045851 |

| Nucleus organization |

0.668734 |

0.212327 |

0.396937 |

0.134765 |

| Transcription |

0.586723 |

0.061277 |

0.490756 |

0.047904 |

| Pseudohyphal growth |

0.523636 |

0.183077 |

0.741094 |

0.154572 |

| DNA metabolic process |

0.520462 |

0.057569 |

0.403555 |

0.03735 |

| Translation |

0.475206 |

0.058331 |

0.32502 |

0.050416 |

| Other |

0.803085 |

0.04149 |

0.791027 |

0.036751 |

| ANOVA test |

F = 3.91, P < 10-13 |

|

F = 7.60, P < 10-15 |

|

| ANCOVA test | F = 2.24, P < 10-4 | F = 4.78, P < 10-15 | ||

a: S.E. denotes the standard error.

Table 2.

The divergence of histone modification code associated with promoter or ORF region of duplicate genes involving in 24 cellular components

| Cellular Component |

DHM-P |

DHM-O |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.E. | Mean | S.E. | |

| Cytoplasm |

0.815386 |

0.022075 |

0.691933 |

0.018111 |

| Mitochondrion |

0.804229 |

0.045602 |

0.775065 |

0.037205 |

| Ribosome |

0.401566 |

0.051071 |

0.21871 |

0.044488 |

| Nucleus |

0.757928 |

0.03278 |

0.633467 |

0.025154 |

| Membrane |

0.867299 |

0.045905 |

0.719912 |

0.037068 |

| Mitochondrial envelope |

0.850156 |

0.071138 |

0.845782 |

0.058631 |

| Nucleolus |

1.041006 |

0.088386 |

0.885202 |

0.076221 |

| Chromosome |

0.848459 |

0.121672 |

0.500084 |

0.069019 |

| Membrane fraction |

0.728517 |

0.057793 |

0.49282 |

0.052274 |

| Cell wall |

0.703015 |

0.05532 |

0.397484 |

0.060315 |

| Vacuole |

0.560115 |

0.090545 |

0.725808 |

0.070671 |

| Golgi apparatus |

1.020564 |

0.07273 |

0.856226 |

0.060742 |

| Cytoplasmic membrane-bounded vesicle |

0.780526 |

0.149402 |

0.703323 |

0.11963 |

| Endomembrane system |

0.77575 |

0.132578 |

0.712372 |

0.098021 |

| Cellular bud |

0.877352 |

0.094858 |

0.65631 |

0.069712 |

| Cytoskeleton |

0.883771 |

0.094073 |

0.589399 |

0.07159 |

| Microtubule organizing center |

0.664255 |

0.193299 |

0.553038 |

0.177284 |

| Site of polarized growth |

0.875764 |

0.0889 |

0.636855 |

0.064332 |

| Endoplasmic reticulum |

0.877175 |

0.081264 |

0.673596 |

0.056244 |

| Plasma membrane |

0.72374 |

0.034621 |

0.70187 |

0.027569 |

| Peroxisome |

0.500936 |

0.245856 |

0.827018 |

0.120535 |

| Extracellular region |

0.553479 |

0.167985 |

0.224751 |

0.129525 |

| Cell cortex |

1.00632 |

0.081755 |

0.650496 |

0.076325 |

| Other |

0.752484 |

0.047213 |

0.632212 |

0.038696 |

| ANOVA test |

F = 3.54, P < 10-7 |

|

F = 6.53, P < 10-15 |

|

| ANCOVA test | F = 1.77, P = 0.01 | F = 4.43, P < 10-10 | ||

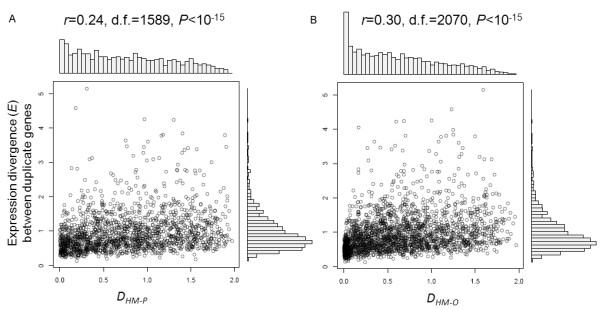

The expression divergence under genetic, epigenetic and stressful perturbations

It is well-documented that gene expression divergence of duplicate genes increases with evolutionary time, but the underlying mechanism remains a subject of debate [30]. The analysis we describe below is to know whether the divergence of HM-mediated regulatory network affects the expression divergence between duplicate genes. We compared the interrelation between the histone modification pattern distance (DHM-P , DHM-O) and the expression distance (E) between duplicate genes, and found that they are significantly correlated (Pearson’s product-moment correlation; DHM-PE: r = 0.24, P < 10-15; DHM-OE: r = 0.30, P < 10-15; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Correlation between the distance of histone modification pattern and the expression divergence (E) of duplicate genes. Relationship between the expression distance and (A) the promoter histone modification divergence (DHM-P) and (B) the ORF histone modification divergence (DHM-O).

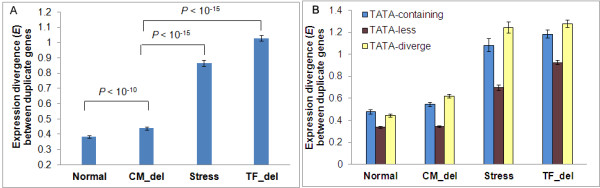

We further divided yeast expression profiles into four types from different perturbation conditions: 1) normal developmental or physiological conditions, defined as ‘Normal’ treatment; 2) a set of conditions where expression changes attribute to environmental stresses, denoted as ‘Stress’ treatment; 3) conditions where single gene coding chromatin modifiers (CM) like SWI/SNF, HDACs, HATs, etc. was deleted, denoted as ‘CM_del’ treatment; 4) conditions where single gene coding transcription factors (TF) was deleted, denoted as ‘TF_del’ treatment. The latter two types are able to test the effect of chromatin modification related proteins and transcription factors on other genes, respectively. We then calculated the expression divergence between duplicate genes under these four types of conditions, denoted by ENormal, EStress, ECM_del, ETF_del, respectively. We observed that the expression distance between duplicate genes in ‘CM_del’ condition (ECM_del) is significantly greater than that in ‘Normal’ condition (ENormal) (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P < 10-10; Figure 7A), but much lower than that in ‘Stress’ and ‘TF_del’ conditions (EStress and ETF_del) (Wilcoxon sum rank test, P < 10-15; Figure 7A). Results imply that histone modification related enzymes and gene associated histone modification profile may indeed influence the expression evolution of duplicate genes, though the relative contribution to the expression divergence between duplicate genes is highly lower than genetic related factors like transcription factors, even externally environmental stresses.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the expression divergence between duplicate genes under different disturbing conditions. (A) The expression divergence between all duplicate genes; (B) The expression divergence between duplicate genes with different status of TATA box. P-value was obtained from Wilcoxon rank sum test using the open-source R statistical analysis language.

TATA-containing genes are usually enriched in stress-related genes [29], and represent high expression variability [31,32]. In our study, we detected that in four disturbed conditions (Normal, Stress, CM-del, TF_del), the expression divergence in TATA-diverge and TATA-containing groups are significantly larger than that in TATA-less duplicate genes (Figure 7B). The discrepancies between expression change and the histone modification divergence in these duplicate gene types (TATA-containing, TATA-less, TATA-diverge) are observed.

Discussion

The divergence of HM profile between duplicate genes

Our detailed analyses on yeast whole-genome histone modification (HM) code profile have shown that duplicate genes share more common HM-code patterns than randomized singleton pairs in their promoter and ORF regions, and the HM-code divergence between duplicates in both regions increase with the sequence divergence. This finding supports the notation that epigenetic divergence between duplicate genes may have been driven by the accumulation of mutations with the duplication time in both their promoter and ORF regions, because it has been shown that the divergence of coding sequence such as KS between yeast duplicates is a proxy to evolutionary time. In other words, no external driving force is needed to explain the HM profile divergence between duplicates, though it remains possible of neofunctionalization based upon divergent HM profile through some positive selection mechanisms.

Hypothesis-based genomic correlation analysis

Genome-wide functional analysis of duplicate genes is in attempt to reveal functional correlation between genetic and epigenetic factors during the process of functional innovation through gene duplication. However, the universal confounding effect of the sequence divergence (KS) has complicated the practical analyses. Consequently, the controversy about the cause-effect interpretation has been inevitable, because genome-wide analysis of duplicate genes has been viewed as an exploration rather than a hypothesis-testing approach.

Since the correlation between the HM profile divergence and the sequence divergence actually reflects the fundamental evolutionary process driven by the accumulation of mutations, we view this as a null hypothesis in the genome-wide functional analysis of duplicate genes. That is, any meaningful inference about the functional correlation within or between genetic and epigenetic elements needs to reject this null hypothesis, as we have shown in this study.

Interaction between genetic and epigenetic elements: who is the driver?

The interaction between epigenetic and genetic elements in gene regulation has been increasingly acknowledged. For instance, the establishment of the histone modification code may partially involve the recruitment of specific histone modifying enzymes such as HATs, HDACs, HMTs by transcription factors (TF) [26]. Meanwhile, the distinctly combinatory histone modification code associated with gene may also provide specific binding code that is read by other transcription factors [21]. These observations raise an interesting question whether the divergence of histone modification code between duplicate genes may co-evolve with trans-acting factors binding to those duplicate genes, e.g., transcription factors, histone modifying enzymes.

We have observed a higher divergence for HM code of duplicate genes in the category of trans-targeted genes than that of controlling genes, suggesting that the change of trans-regulators binding to duplicate genes may affect the pattern of HM code in both promoter and ORF regions, and thus accelerating the divergence of histone modification code between duplicate genes. Yet, it remains unclear about the cause-effect relationship. For instance, does the divergence of trans-regulators to duplicate genes facilitate the divergence of histone modification between duplicate genes, or vice versa? Our further study will address this issue.

Functional preference in the HM code divergence between duplicate genes

We observed the functional bias on the HM-code divergence after gene duplication. One possibility is that histone proteins associated with genes in different biological functions may be subject to differentially post-translational modification, leading to different divergence rate of histone modification code between duplicate genes. Since histone modification process of one gene largely depends on its chromatin environment and DNA sequence interacted by histone modifying enzymes [33], functionally selective constraints may also be imposed on histone modification evolution associated with that gene, a situation similar to DNA sequence evolution.

Conclusions

In this study, we unveiled the evolution of yeast histone modification code since gene duplication. Though duplicate genes represent functional redundancy at histone modification level compared with single-copy genes, the histone modification divergence occurred along with evolutionary time (KS as the proxy), which possibly due to the coding sequence evolution after gene duplication. Moreover, the histone modification code in ORF region evolves slower than that in promoter region, indicative of functionally selective constraints on protein sequences. Going further, after controlling the confounding effect of the coding sequence divergence (KS), the histone modification code co-evolves with cis- (TATA box) and trans- (TF and trans-acting eQTL) regulatory factors, confirmed by the fact that the histone modification code is shaped by the combined interaction among histone-modifying enzymes, trans-acting elements and cis-regulatory motif. In addition, histone modification makes contribution to the expression divergence between duplicate genes, despite the minor effect compared to transcription factors and environmental stresses. Taking together, we provided the evidence of the co-evolution between genetic and epigenetic elements since gene duplication, together contributing to the expression divergence between duplicate genes.

Methods

Data of yeast histone modification pattern

Genome-wide histone modification pattern data of Saccharomyces cerevisiae were downloaded from ChromatinDB [34] ( http://www.bioinformatics2.wsu.edu/cgi-bin/ChromatinDB/cgi/visualize_select.pl). ChromatinDB provides the user with easy access to ChIP-microarray data for a large set of histones or histone modifications in S. cerevisiae, which includes 17 distinct histone modification combinations like dimethylation in Lys4 of histone H3 (H3K4me2), acetylation in Lys12 of histone H4 (H4K12ac), etc. and 5 histone protein occupancy levels (H2A, H2B, H3, H4, H2A.Z). We applied log base-2 of average enrichment ratio with nucleosome-normalizing for each of 22 histone modification data in promoter and open reading frame (ORF) regions of genes.

Yeast microarray expression data

A total of 84 microarray expression data points of S. cerevisiae whose expression changes are attributing to internal disturbing like developmental or physiological conditions were respectively collected [35-37]. This type was defined as “Normal” conditions, which are not genetically perturbed by regulatory network related elements like transcription factors and chromatin modifiers (CM) or other environmental stresses. We collected 170 gene expression profiles of yeast strains mutated for various chromatin modifiers from 26 publications [38]. We called this type of expression profile data as ‘CM_del’ conditions. Expression profile data of 263 transcription factor-deletion experiments were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the series accession number GSE4654 [39]. Similarly, this type was denoted as ‘TF_del’ experiments. A total of 504 cDNA microarray data points of yeast whose expression changes are attributing to environmental stresses were collected [9]. We call this type as ‘Stress’ conditions. Normalization was done as each original paper recommended.

Data of trans- and cis- regulatory elements

Transcription factor (TF)-DNA binding profiles of yeast were downloaded from Lee et al. [40] and Harbison et al. [41]. In the study of Harbison et al. (2004), we just used 203 DNA-binding transcription factors in rich media conditions, regardless of 84 regulators in environmental stressed conditions. Most transcription factors in two studies are overlapped. Finally, we obtained 207 TF-all S. cerevisiae genes binding interaction profiles. For each gene, a p-value was assigned to measure the probability of true TF-target interaction; a smaller p-value means the interaction is more likely. Here, we used relatively stringent significance level of 0.001 as cutoff to define the status of TF-target gene interaction. Two studies together determine all TF-target gene interactions, and we observed that 3183 genes are binding by at least one transcription factor (TF-targeted genes). Yeast genomic expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) data were downloaded from Brem and Kruglyak [42]. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney (WMW) test with the criterion of 50 kb interval was conducted to detect and define eQTL regions [9]. Finally, we obtained 2775 genes which at least have one trans-acting eQTL (trans-eQTL acting genes). Thus, we can divide all yeast genes into two categories, trans-targeted genes and controlling genes, where trans-targeted genes are the union of TF-targeted genes and trans-eQTL acting genes, while controlling genes are the reminders. Since trans-eQTL acting genes were not only regulated by transcription factors, but most by chromatin related enzymes and other factors [43], trans-targeted genes may have the possibility to be regulated by all trans-regulators, not restricted to transcription factors.

There are two types of genes, TATA-containing genes and TATA-less genes [29]. We classified all duplicate pairs into three categories, TATA-containing, TATA-less and TATA-diverge pairs. TATA-containing and TATA-less types are those duplicate pairs where both copies have or don’t have TATA box, respectively, while TATA-diverge type refers to duplicate pairs where one copy belongs to TATA-containing genes, and the other TATA-less genes.

Protein subcellular localization and biological process

The information of protein localization and biological process for S. cerevisiae was defined by the Gene Ontology (GO) classification, and downloaded from Saccharomyces Genome Database. GO Slim was used to classify 24 cellular component sorts and 37 biological process categories. A duplicate gene pair was assigned to a GO Slim term if both duplicate copies are belonging to this GO term, or one copy is belonging to while the other is not annotated.

Defining functional divergence between yeast duplicate genes

There are two types of histone modification profiles, histone modification pattern associated with gene promoter region and open reading frame (ORF) region. One minus Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient (1-r) was used to determine the distance of these two types of histone modification pattern between duplicate genes, shortly denoted as DHM-P for promoter histone modification distance and DHM-O for ORF histone modification distance.

We modified the Czekanowski-Dice formula [44] to calculate the distance of transcription factors or trans-acting eQTLs shared by duplicate gene 1 and 2 in a duplicate pair, shortly denoted as DTF and Dt-eQTL, respectively. Suppose Δ12 be the number of TFs or trans-acting eQTLs that differ between one duplicate pair; y1∪y2 be the number of TFs or trans-acting eQTLs that regulate at least one of duplicate genes, and y1∩y2 be the number of shared TFs or trans-acting eQTLs between a duplicate pair. Then, the TF distance or trans-acting eQTL distance between duplicate genes 1 and 2 is defined as follows:

| (1) |

Apparently, the greater the value, the higher degree of TF or trans-acting eQTL divergence between duplicate genes.

We used evolutionary distance (E) defined by Gu et al. [5] as the measure of expression divergence between duplicate genes of four types, shortly denoted as ENormalECM_delETF_del and EStress for ‘Normal’, ‘CM_del’, ‘TF_del’ and ‘Stress’ experiments, respectively. Specifically, for any duplicate gene 1 and 2, let x1k and x2k be its expression level, respectively, in the kth microarray experiment; and be the mean of expression level in kth microarray experiments, respectively, where k = 1,…m. The formula of the expression distance (E) between gene 1 and 2 is as follows:

| (2) |

Determination of yeast duplicate pairs

The method of Gu et al. [45] was applied to identify duplicate genes. As the criterion of 80% alignable regions between protein sequences is too stringent, and may miss some duplicate genes, we reduced this criterion to 50%. All pairs of duplicate genes in each gene family were used for the analysis. The reminders of S. cerevisiae genes were considered as singleton genes. The rate of synonymous substitutions (KS) and nonsynonymous substitutions (KA) between duplicate genes were estimated using PAML [46] with default parameters.

Abbreviations

HATs: Histone acetyltransferases; HDACs: Histone deacetylases; HMTs: Histone methyltransferases; HDMs: Histone demethylases; KS: The rate of synonymous substitutions; KA: The rate of nonsynonymous substitutions; TF: Transcription factor; eQTLs: Expression quantitative trait loci; ORF: Open reading frame; HM: Hitone modification; ANOVA: Analysis of variance; ANCOVA: Analysis of covariance; GO: Gene ontology; CM: Chromatin modifiers.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

YZ designed and performed the study, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. ZS and WH analyzed the data. XG designed the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figures S1-S2. are available at online web site of BMC Evolutionary Biology journal.

Contributor Information

Yangyun Zou, Email: yyzou@fudan.edu.cn.

Zhixi Su, Email: zxsu@fudan.edu.cn.

Wei Huang, Email: weih@iastate.edu.

Xun Gu, Email: xungufudan@gmail.com.

Acknowledgements

We thank Libing Shen for his suggestion on English writing when we prepare the manuscript. This work was supported by the grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology China (2012CB910101 to ZS).

References

- Innan H, Kondrashov F. The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Force A. The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics. 2000;154:459–473. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. Evolution by gene duplication. Berlin: Springer; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JS, Raes J. DUPLICATION AND DIVERGENCE: The evolution of new genes and old ideas. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:615–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Zhang Z, Huang W. Rapid evolution of expression and regulatory divergences after yeast gene duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:707–712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409186102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach LJ, Zhang Z, Lu C, Kearsey MJ, Luo Z. The role of cis-regulatory motifs and genetical control of expression in the divergence of yeast duplicate genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2556–2565. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp B, Pal C, Hurst L. Evolution of cis-regulatory elements in duplicated genes of yeast. Trends Genet. 2003;19:417–422. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Gu J, Gu X. How much expression divergence after yeast gene duplication could be explained by regulatory motif evolution? Trends Genet. 2004;20:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Su Z, Yang J, Zeng Y, Gu X. Uncovering genetic regulatory network divergence between duplicate genes using yeast eQTL landscape. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312B:722–733. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou YY, Huang W, Gu ZL, Gu X. Predominant gain of promoter TATA box after gene duplication associated with stress responses. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2893–2904. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp RA, Wendel JF. Epigenetics and plant evolution. New Phytol. 2005;168:81–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin S, Riggs A. Epigenetic silencing may aid evolution by gene duplication. J Mol Evol. 2003;56:718–729. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin SN, Parkhomchuk DV. Position-associated GC asymmetry of gene duplicates. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:372–384. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2631-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin SN, Parkhomchuk DV, Rodin AS, Holmquist GP, Riggs AD. Repositioning-dependent fate of duplicate genes. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:529–542. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D. Asymmetric histone modifications between the original and derived loci of human segmental duplications. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R105. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:295–304. doi: 10.1038/nrg2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert N, Thomson I, Boyle S, Allan J, Ramsahoye B, Bickmore WA. DNA methylation affects nuclear organization, histone modifications, and linker histone binding but not chromatin compaction. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:401–411. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binz T, D'Mello N, Horgen PA. A comparison of DNA methylation levels in selected isolates of higher fungi. Mycologia. 1998;90:785–790. doi: 10.2307/3761319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Glasner ME, Yekta S, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Vertebrate microRNA genes. Science. 2003;299:1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1080372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Carey M, Workman JL. The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell. 2007;128:707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Steensel B. Mapping of genetic and epigenetic regulatory networks using microarrays. Nat Genet. 2005;37:S18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar CB, Grunstein M. Genome-wide patterns of histone modifications in yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:657–666. doi: 10.1038/nrm1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdistani SK, Grunstein M. Histone acetylation and deacetylation in yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:276–284. doi: 10.1038/nrm1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterner DE, Grant PA, Roberts SM, Duggan LJ, Belotserkovskaya R, Pacella LA, Winston F, Workman JL, Berger SL. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:86–98. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoist C, Chambon P. In vivo sequence requirements of the SV40 early promoter region. Nature. 1981;290:304–310. doi: 10.1038/290304a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basehoar AD, Zanton SJ, Pugh BF. Identification and distinct regulation of yeast TATA box-containing genes. Cell. 2004;116:699–709. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W-H, Yang J, Gu X. Expression divergence between duplicate genes. Trends Genet. 2005;21:602–607. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirosh I, Weinberger A, Carmi M, Barkai N. A genetic signature of interspecies variations in gene expression. Nat Genet. 2006;38:830–834. doi: 10.1038/ng1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry CR, Lemos B, Rifkin SA, Dickinson WJ, Hartl DL. Genetic properties influencing the evolvability of gene expression. Science. 2007;317:118–121. doi: 10.1126/science.1140247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suganuma T, Workman JL. Crosstalk among Histone Modifications. Cell. 2008;135:604–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TR, Wyrick JJ. ChromatinDB: a database of genome-wide histone modification patterns for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1828–1830. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman PT, Sherlock G, Zhang MQ, Iyer VR, Anders K, Eisen MB, Brown PO, Botstein D, Futcher B. Comprehensive identification of cell cycle-regulated genes of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae by microarray hybridization. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:3273–3297. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S, DeRisi J, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown PO, Herskowitz I. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science. 1998;282:699–705. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RJ, Campbell MJ, Winzeler EA, Steinmetz L, Conway A, Wodicka L, Wolfsberg TG, Gabrielian AE, Landsman D, Lockhart DJ, Davis RW. A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of the mitotic cell cycle. Mol Cell. 1998;2:65–73. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld I, Shamir R, Kupiec M. A genome-wide analysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae demonstrates the influence of chromatin modifiers on transcription. Nat Genet. 2007;39:303–309. doi: 10.1038/ng1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Killion PJ, Iyer VR. Genetic reconstruction of a functional transcriptional regulatory network. Nat Genet. 2007;39:683–687. doi: 10.1038/ng2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Robert F, Odom DT, Bar-Joseph Z, Gerber GK, Hannett NM, Harbison CT, Thompson CM, Simon I, Zeitlinger J, Jennings EG, Murray HL, Cordon DB, Ren B, Wyrick JJ, Tagne JB, Volkert TL, Fraenkel E, Gifford DK, Young RA. Transcriptional regulatory networks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 2002;298:799–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1075090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison CT, Gordon DB, Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Macisaac KD, Danford TW, Hannett NM, Tagne J-B, Reynolds DB, Yoo J, Jennings EG, Zeitlinger J, Pokholok DK, Kellis M, Rolfe PA, Takusagawa KT, Lander ES, Gifford DK, Fraenkel E, Young RA. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2004;431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brem RB, Kruglyak L. The landscape of genetic complexity across 5,700 gene expression traits in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1572–1577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408709102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, Kim Y-J. Epigenetic regulation and the variability of gene expression. Nat Genet. 2008;40:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Brun C, Remy E, Mouren P, Thieffry D, Jacq B. GOToolBox: functional analysis of gene datasets based on Gene Ontology. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R101. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z, Cavalcanti A, Chen F-C, Bouman P, Li W-H. Extent of Gene Duplication in the Genomes of Drosophila, Nematode, and Yeast. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:256–262. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Bielawski JP. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol Evol. 2000;15:496–503. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01994-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figures S1-S2. are available at online web site of BMC Evolutionary Biology journal.