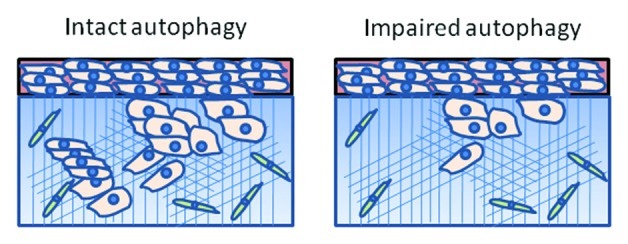

Of the hallmarks of cancer,1 the process of invasion and metastases is arguably the least well-understood and therefore least drugable. Invasion through the extracellular matrix is arguably the critical distinction between carcinoma in situ and carcinoma with metastatic potential. Efforts to understand targetable mechanisms of cancer invasiveness are sorely needed. In a recent issue, Macintosh et al. provided evidence that autophagy, the degradative process by which cells sequester and recycle cytoplasmic components, plays a role in tumor cell invasion.2 Using a glioma cell line expressing a doxycycline-inducible shRNA directed against the essential autophagy gene ATG12, the effects of autophagy inhibition in two-dimensional (2D) culture and a three-dimensional (3D) organotypic culture system was studied. Knockdown of ATG12 had no significant impact on many cellular functions in 2D culture, including profileration, vaibility and migration. However, knockdown of ATG12, compared with non-target knockdown, resulted in a reduced capacity to invade an organotypic matrix consisting of human fibroblasts embedded in polymerized collagen (Fig. 1). Since efforts are underway to target autophagy therapeutically in cancer,3 the authors conclude that autophagy represents a drugable mechanism of tumor cell invasion.

Figure 1. Autophagy contributes to tumor cell invasion. In a 3D oragnotypic culture system consisting of glioma cells (pink) collagen matrix (blue) containing embedded fibroblasts (green), glioma cell invasion of the extracellular matrix was reduced in cells deficient in the essential autophagy gene ATG12.

This study provides further evidence that autophagy can contribute to the malignant phenotype of cancer cells and could be a therapeutic target in certain cancers. The results also underscore a recurring theme in autophagy research, that cellular phenotypes of autophagy modulation are more pronounced within the tumor microenvironment than in traditional 2D culture. In an ovarian cancer model, acute activation of the ARHI tumor suppressor gene induced autophagic cell death in vitro but autophagic cell survival in vivo.4 In a study of aggressive and indolent melanoma cell lines, elevated autophagy levels did not correlate with proliferation or invasion in 2D culture, but did correlate with invasion of a collagen matrix in 3D culture and tumor growth rate in vivo.5 Together with the work by Macintosh et al., there is a growing body of evidence that while 2D culture can provide important insights into autophagy’s role in cancer, experiments done within a 3D model system that includes elements of the tumor microenvironment are critical to understanding the functional consequences of autophagy modulation.

Can impairment of other components of autophagy produce reduced invasion? Currently, the only autophagy inhibitor that is in clinical trials is hydroxychloroquine, which blocks the lysosome.3 While ATG12 is not currently a druggable target, emerging autophagy inhibitors may be able to target other components of autophagic vesicle assembly. Testing the effects of pharmacological autophagy inhibitors targeting proximal and distal components on tumor cell invasion will be important. It will also be critical to test the effects of genetic and pharmacological autophagy inhibition on a larger number of cell lines from a wider variety of malignancies.

Understanding the mechanism by which autophagy regulates tumor cell invasion will also be equally important. Tumor cell invasion is a complex phenomenon that includes diverse molecular pathways including secretion of metalloproteases, generation of lipid signaling molecules, signaling through integrin-associated kinases, such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), and massive rearrangement of cytoskeleton.6 Interestingly, autophagy has been implicated in many of these processes already. For instance, autophagy has been shown to be required for secretion of certain proteins7 and regulation of sphingosine derivatives.8 Finally, an intimate link has been found between autophagy and FAK signaling. One of the essential autophagy genes is FIP (FAK interacting protein) 200,9 and, more recently, reduced FAK signaling, which occurs in a dynamic manner during invasion, was shown to be a strong inducer of cytoprotective autophagy.10

It will be important to understand how to capitalize on autophagy’s role in promoting tumor cell invasion. Additional studies in models of advanced disease including in vivo studies will be required to understand the role of autophagy inhibitors as cancer invasion inhibitors. Future work will be needed to determine if the transition from premalignant noninvasive cells to malignant invasive cancer cells also relies on autophagy. If this were the case, autophagy inhibitors could not only be effective chemotherapeutic, but also chemoprevention agents.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/22147

References

- 1.Hanahan D, et al. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macintosh RLTP, et al. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2022–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.20424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaravadi RK, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:654–66. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Z, et al. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3917–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI35512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma XH, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3478–89. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedl P, et al. Cell. 2011;147:992–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manjithaya R, et al. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:537–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavieu G, et al. Autophagy. 2007;3:45–7. doi: 10.4161/auto.3416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wei H, et al. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1510–27. doi: 10.1101/gad.2051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandilands E, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;14:51–60. doi: 10.1038/ncb2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]