Abstract

Histogenesis of the auditory system requires extensive molecular orchestration. Recently, Dicer1, an essential gene for generation of microRNAs, and miR-96 were shown to be important for development of the peripheral auditory system. Here, we investigated their role for the formation of the auditory brainstem. Egr2::Cre-mediated early embryonic ablation of Dicer1 caused severe disruption of auditory brainstem structures. In adult animals, the volume of the cochlear nucleus complex (CNC) was reduced by 73.5%. This decrease is in part attributed to the lack of the microneuronal shell. In contrast, fusiform cells, which similar to the granular cells of the microneural shell are derived from Egr2 positive cells, were still present. The volume reduction of the CNC was already present at birth (67.2% decrease). The superior olivary complex was also drastically affected in these mice. Nissl staining as well as Vglut1 and Calbindin 1 immunolabeling revealed that principal SOC nuclei such as the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body and the lateral superior olive were absent. Only choline acetyltransferase positive neurons of the olivocochlear bundle were observed as a densely packed cell group in the ventrolateral area of the SOC. Mid-embryonic ablation of Dicer1 in the ventral cochlear nucleus by Atoh7::Cre-mediated recombination resulted in normal formation of the cochlear nucleus complex, indicating an early embryonic requirement of Dicer1. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of miR-96 demonstrated low expression in the embryonic brainstem and up-regulation thereafter, suggesting that other microRNAs are required for proper histogenesis of the auditory brainstem. Together our data identify a critical role of Dicer activity during embryonic development of the auditory brainstem.

Introduction

Normal hearing requires proper development of the central auditory system. After transduction of acoustic signals in the cochlea, all auditory information is transmitted by spiral ganglion neurons to the central auditory system for signal processing and perception [1], [2]. The first central structure to process auditory information is the cochlear nucleus complex (CNC) [1], [2]. It is the sole intermediary between the periphery and higher centers of the central auditory system and distributes information to different ascending pathways [1]. Anatomically, the CNC is a tripartite structure consisting of the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN), the posteroventral cochlear nucleus (PVCN), and the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN) [3]. DCN neurons primarily project to the inferior colliculus [3]. The major targets of the VCN are the lateral superior olive (LSO), the medial superior olive (MSO), and the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), which constitute the major nuclei of the SOC [3], [4]. The SOC represents the first binaural processing center and participates in sound localization by computing interaural time and level differences [3], [5]. In addition, neurons within the SOC give rise to the olivocochlear (OC) bundle, an efferent feedback system, that modulates cochlear function [6].

Due to their prominent role in auditory information processing, both the CNC and SOC have been extensively characterized with respect to electrophysiological properties [7]–[9], molecular profiles [10]–[13], and maturation processes [14], [15]. Much less is known concerning their histogenesis. Genetic analyses in mice identified rhombomeres (r) 2 to 5 as the major source of the CNC [16], [17], and established r3 and r5 as the origin of many principal SOC neurons [18]. However, the genetic program, underlying histogenesis of these two auditory structures, is largely unknown. Only recently, the proneural basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Atoh1 was shown to be important for histogenesis of the CNC and SOC [18].

Several studies identified a central role of microRNAs (miRNA) for proper formation and function of neuronal circuits. miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression on the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level [19]–[21]. They are generated in vivo from long primary (pri-) miRNAs, which require final processing by Dicer, a ribonuclease type III endonuclease which recognizes double-stranded RNA molecules [22]. Dicer activity results in mature miRNAs of 21–27 nts that interact with complementary mRNA sequences. Target recognition is based on the complementarity between the seed region (nucleotides 2–8) of a miRNA and the mRNA [23]. Binding to the target mRNA results in translational repression or mRNA cleavage, thereby offering a novel layer of gene regulation [21], [24], [25].

The number of Dicer-like proteins varies among organisms. Whereas organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster [26], plants [27], and fungi [28] possess multiple Dicer-like proteins, mammals have only one gene, Dicer1 [29]. Ablation of Dicer1 in mice severely disrupts miRNA pathways, resulting in loss of the inner cell mass of the blastocyst and embryonic arrest at E7.5 [29]. To further study the role of miRNAs and Dicer, conditional alleles of Dicer1 have been generated [30]–[32]. This approach identified numerous functions of miRNAs in the nervous system such as their regulatory role in neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, differentiation, and plasticity [21], [24], [33], [34]. These small RNAs were also shown to regulate many sensory systems such as the visual [35]–[37] and olfactory systems [38], [39], taste [40], [41], CO2 sensing [42], and pain perception [43]. Studies in the auditory system revealed an essential role of miRNAs in the cochlea. Early embryonic (∼E8.5) ablation of Dicer1 in the otic placode using a Foxg1::Cre driver line resulted in near complete loss of the ear and the neurosensory epithelium [44], and depletion using a Pax2::Cre driver line gave rise to disorganized inner and outer hair cell rows and lack of innervation of the sensory epithelium by the auditory nerve [45]. Later ablation of Dicer1 at E14.5 resulted in postnatal malformation of hair cells such as loss or disorganization of stereocilia [46]. Furthermore, mutations in miR-96 are associated with peripheral hearing loss both in man and mouse [47]–[49]. In the mouse this is caused by arresting physiological and morphological development of cochlear hair cells around birth [47]–[49].

Here we investigated the role of Dicer1 for the development of the auditory brainstem by analyzing two different mouse lines with differentially timed disturbance in miRNA function. In one mouse line, Egr2::Cre;Dicer1fl/fl, Dicer is deleted in r3 and r5 from early embryonic stages on, whereas in the other mouse line, Atoh7: Cre;Dicer1fl/fl, the enzyme is deleted from mid embryonic stages on in bushy cells of the VCN. Anatomical and immunohistochemical analyses of these mouse lines identified a critical early role of Dicer in histogenesis of the CNC and SOC. Expression analyses of miR-96 suggested the involvement of other miRNAs in histogenesis of the auditory brainstem.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All protocols were in accordance with the German Animal Protection law and approved by the local animal care and use committee (LAVES, Oldenburg 33.9-42502-04-10/0235) and the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tel Aviv University (M-09-057). Protocols also followed the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Animals

The Dicer1fl/fl mouse [31], the ROSA26R mouse [50], and the Cre-driver lines Egr2::Cre [51] and Atoh7::Cre [52] have been described previously. Littermates that carry the incomplete combination of alleles served as wild type controls. All animals used for these experiments were maintained on mixed backgrounds.

Immunodetection, β-galactosidase Staining, and Histology

Rabbit anti-Vglut1 antibody was a generous gift from Dr. S. El Mestikawy (Creteil, Cedex, France) [53], rabbit anti-ChAT was obtained from Millipore (Schwalbach, Germany), and goat anti-Calbindin 1 from Swant (Marly, Switzerland). Antibodies were diluted 1∶1,000 (anti-Vglut1), 1∶150 (anti-ChAT), and 1∶5,000 (anti-Calbindin 1) with carrier solution containing 1–2% bovine serum albumin, 10% goat serum (for anti-Vglut1), and 0.3–0.5% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na-phosphate, pH 7.4). Sections were incubated overnight with agitation at 7°C. They were then rinsed three times for 10 min with washing solution (0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.1% saponin in PBS, again transferred in carrier solution and treated with the secondary antibody (diluted 1∶500 to 1∶1,000, Invitrogen). After several washes in washing solution and PBS, images were taken with a BZ 8100 E fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Neu-Isenburg, Germany).

For β-galactosidase staining, Egr2::Cre;ROSA26R mice were perfused by 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were then cryosectioned at 60 µm in free floating conditions and stained in X-gal solution (3 mg/ml X-gal, 7.2 mM Na2HPO4, 2.8 mM NaH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM K3(Fe(CN)6), 3 mM K4(Fe(CN)6, 1% NP-40) for 24–48 hours at 37°C.

Nissl staining was performed on 30-µm-thick sections. The volume of the auditory nuclei was calculated by multiplying the outlined area with the thickness of each section. Two animals were used for each genotype at each age, resulting in 4 auditory nuclei per analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test.

Tissue Preparation and RT-PCR Analysis

Mice were anesthetized with 7% chloral hydrate (60 µl/g body weight) and decapitated. The brainstem was dissected and 250-µm-thick coronal slices, containing the CNC or SOC, were cut with a vibratome (Leica VT 100 S, Leica, Nussloch, Germany) under binocular control. Collected tissue was stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Darmstadt, Germany) at -20°C. After DNA extraction from the tissue, the following primer pairs were used for genotyping: 460R GTACGTCTACAATTGTCTATG, 23F ATTGTTACCAGCGCTTAGAATTCC and 458F TCGGAATAGGAACTTCGTTTAAAC [31]. Total RNA extraction from tissue was performed using acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction [54]. After reverse transcription, PCR reactions were performed with the primer pair: exon20fn GACACTGTCAAATGCCAGTG and exon24rev GCCTTGGGGACTTCGATATC. This primer combination amplifies a 1,500 bp long fragment from wild type Dicer1 mRNA and a 360 bp fragment of the truncated mRNA after genetic recombination. PCR products were separated by standard agarose gel electrophoresis and GelRED (Genaxxon, Ulm, Germany) to stain nucleic acids.

For miR-96 expression analysis, the brainstem was dissected from C57BL/6 mice at E18, P0 and P25 and small RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was transcribed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) and miR-96 taq-man primer UUUGGCACUAGCACAUUUUUGCU designed by Applied Biosystems. For the qRT-PCR reaction, miR-96 probe (Applied Biosystems) and FastStart Universal Probe Master Mix (Roche) were used in the StepOne Plus qRT-PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). U6B served as endogenous control. At least 3 experiments were conducted, with triplicates.

Results

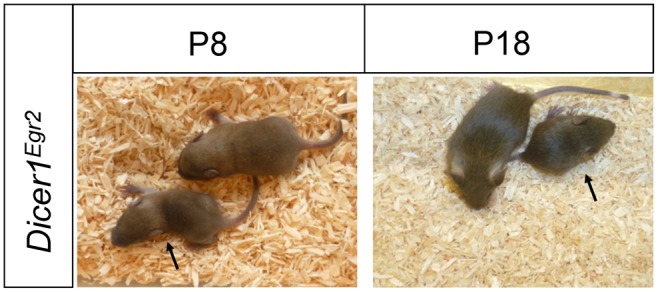

Egr2::Cre-mediated Loss of Dicer1 Disrupts Formation of the CNC

To determine the role of miRNAs for proper development of the auditory brainstem, we used a Dicer1fl/fl mouse line with loxP sites flanking exons 23 and 24 of the Dicer1 gene [31]. These two exons encode the majority of both RNase III domains. The mouse line was paired with the Cre-driver line Egr2::Cre (aka Krox20::Cre), which drives Cre expression specifically in r3 and r5 [51]. These two rhombomeres are the major source of CNC and SOC neurons [16], [18]. Egr2::Cre;Dicer1fl/fl animals (Dicer1Egr2 in the following) were born in a non-mendelian ratio and became smaller than their littermates with increased age (Fig. 1). In addition, few Dicer1Egr2 animals survived beyond the first postnatal days. One explanation might be malfunction of the respiratory system, as Egr2 positive cells contribute to the parafacial respiratory group [55], [56], which is part of the brainstem respiratory neuronal network.

Figure 1. Smaller size of Dicer1Egr2 mice. Compared to wild type littermates, Dicer1Egr2 mice (black arrows) were smaller and the difference in size increased with age.

P, postnatal day.

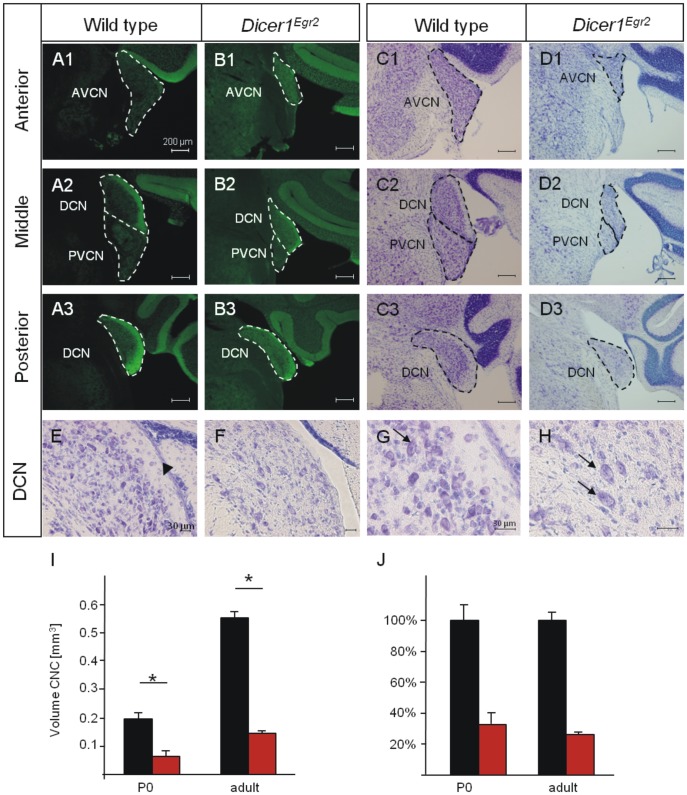

To analyze formation of the CNC in Dicer1Egr2 mice, we performed immunohistochemistry against Vglut1 in mice aged >P22 (adult mice in the following). This presynaptic marker labels the inputs of the spiral ganglion neurons into the CNC [57]. Accordingly, Vglut1 labeling was observed in all three subdivisions, the DCN, the AVCN, and the PVCN, of Dicer1fl/fl control animals (Fig. 2A). In Dicer1Egr2 mice, all three nuclei were labeled but appeared decreased in size compared to control animals (Fig. 2B). Most evident, the granular cells constituting the microneuronal shell of the CNC [58]–[60] are absent in the CNC (Fig. 2A,B). Nissl stained sections confirmed the loss of these cells in Dicer1Egr2 mice (Fig. 2E,F). This is in agreement with the origin of granular cells in r3 and r5 [16]. To determine whether other cell types with ascertained embryonic origin in these two rhombomeres were absent as well, we analyzed fusiform cells [16]. They represent large output neurons from the DCN and are situated beneath the microneuronal shell. Due to their large size, they can readily be identified in Nissl stained sections. In contrast to granular cells, these large output neurons were present in both wild type and Dicer1Egr2 mice (Fig. 2G,H). These data indicate different dependency of CNC neurons on Dicer or different effectiveness of recombination [44], [45].

Figure 2. Malformed CNC in adult Dicer1Egr2 mice.

A,B, Vglut1 immunoreactivity in the cochlear nucleus complex of adult wild type (P22– P30) (A) or Dicer1Egr2 mice (B) at anterior (A1,B1), middle (A2,B2) or posterior levels (A3,B3). C,D , Nissl staining of CNC sections of wild type (C) or Dicer1Egr2 mice (D) at anterior (C1,D1), middle (C2,D2) or posterior levels (C3,D3) levels. All three subnuclei, i.e. the AVCN, PVCN, and DCN display a reduced size. E–H Nissl stained sections of the DCN (E,F) reveal absence of the microneuronal shell (black arrow), but presence of fusiform cells (black arrows) (G,H) in Dicer1Egr2 mice. I, The volume of the CNC was determined at P0 or adult stage from Nissl stained serial sections. A significant decrease in volume of the CNC was observed in Dicer1Egr2 mice at both ages (2 animals per genotype, aged P0 or P22 and P30) (Mann-Whitney U-test, *, P<0.05). J, The relative decrease in volume in Dicer1Egr2 mice was similar between P0 and adult mice. AVCN, anteroventral cochlear nucleus; DCN, dorsal cochlear nucleus; PVCN, posterior ventral cochlear nucleus. Dorsal is up, lateral is to the right.

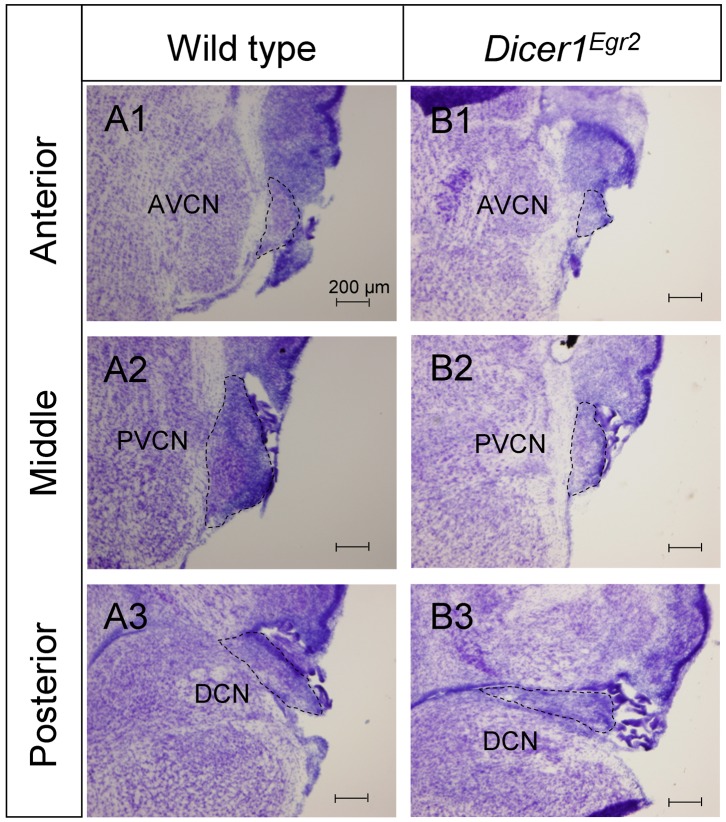

Next, we quantified the volume change in Nissl stained coronal sections (Fig. 2C,D). The lack of the microneuronal shell precluded delineation of the tripartite division in Dicer1Egr2 mice at the transition between the different nuclei. We therefore restricted our volume analysis to the entire CNC. The volume was significantly decreased by 73.5% in Dicer1Egr2 mice compared to control animals (WT: 0.55±0.03 mm3; Dicer1Egr2 0.15±0.01 mm3, P = 0.021) (Fig. 2I). To investigate, whether the CNC was already disrupted at birth, we performed Nissl staining in P0 tissues (Fig. 3A,B). Quantification of the CNC volume revealed a reduction by 67.2% (WT: 0.197±0.02 mm3, Dicer1Egr2: 0.065±0.017 mm3, P = 0.034) (Fig. 2I), which was very similar to the decrease observed in adult tissue (Fig. 2J). These data demonstrate that proper formation of the CNC depends on Dicer.

Figure 3. Malformed CNC in P0 Dicer1Egr2 mice.

A,B, Nissl stained sections of the cochlear nucleus complex of wild type (A) or Dicer1Egr2 mice aged P0 (B) at anterior (A1,B1), middle (A2,B2) or posterior (A3,B3) levels. All three subnuclei, i.e. the AVCN, PVCN, and DCN display a reduced size. AVCN, anteroventral cochlear nucleus; DCN, dorsal cochlear nucleus; PVCN, posterior ventral cochlear nucleus. Dorsal is up, lateral is to the right.

Egr2::Cre-mediated Loss of Dicer1 Prevents Formation of the SOC

The severe disruption of the VCN should entail a decreased number of projections into the SOC. We hence performed Vglut1 immunohistochemistry in the SOC. This marker labels the excitatory inputs which originate in the VCN and represent the major projections into the SOC [61]. In adult control animals, the MNTB and the U-shaped LSO were intensely labeled (Fig. 4A). In contrast, only weak immunoreactivity was observed in Dicer1Egr2 animals and the labeling was restricted to very ventral positions in the SOC (Fig. 4B). These data confirm severe reduction of the VCN and its projections and indicate disrupted organization of the SOC.

Figure 4. Severe disruption of the SOC in Dicer1Egr2 mice.

A–F Vglut1 immunoreactivity (A,B), Calb1 immunoreactivity (C,D), or Nissl stained sections (E,F) in the superior olivary complex of adult (P22– P30) wild type (A,C,E) or Dicer1Egr2 mice (B,D,F). Only weak Vglut1 staining is observed in the SOC of Dicer1Egr2 mice and principal nuclei such as the MNTB or the U-shaped LSO cell group are absent in these animals. Calb1 labeling is observed in somata of MNTB neurons and in the neuropil of the LSO, MSO, and SPN in wild type mice. No labeling is observed in Dicer1Egr2 mice. In Nissl stained sections, the cell groups of the MNTB and LSO are recognizable in control mice, but not in Dicer1Egr2 mice. The cell group at the ventral part in Dicer1Egr2 mice corresponds to the olivocochlear neurons. G–J Vglut1 immunoreactivity (G,H), or Nissl stained sections (I,J) in the superior olivary complex of P0 wild type (G,I) or Dicer1Egr2 mice (H,J). Vglut1 staining is restricted to the olivocochlear neurons in the SOC of Dicer1Egr2 mice, and principal nuclei such as the MNTB or the LSO cell group are absent in these animals. In Nissl stained sections, the cell groups of the MNTB and LSO are recognizable in wild type mice, but not in Dicer1Egr2 mice. The cell group at the ventral part in Dicer1Egr2 mice corresponds to the olivocochlear neurons. LSO, lateral superior olive; MNTB, medial nucleus of the trapezoid body; MSO, medial superior olive; OCN, olivocochlear neurons; SPN, superior paraolivary nucleus. Dorsal is up, lateral is to the right.

To further study the SOC, we performed immunohistochemistry against Calbindin 1 (Calb1), a small cytoplasmic calcium binding protein. In agreement with a previous study in the closely related rat [62], Calb1 labeled virtually all somata of MNTB neurons as well as the neuropil of LSO, the MSO, and the superior paraolivary nucleus (Fig. 4C,D). In striking contrast, no Calb1 labeling was observed in Dicer1Egr2 animals in the SOC area. These data indicate absence of major nuclei of the mouse SOC such as the MNTB and LSO. To corroborate this finding, we performed Nissl staining of adult tissue. In agreement with the absence of Calb1 immunolabeling in Dicer1Egr2 animals, we noticed complete lack of the MNTB in coronal sections (Fig. 4E,F). In addition, no U-shaped cell group corresponding to the LSO (Fig. 4E,F) could be detected in Dicer1Egr2 mice.

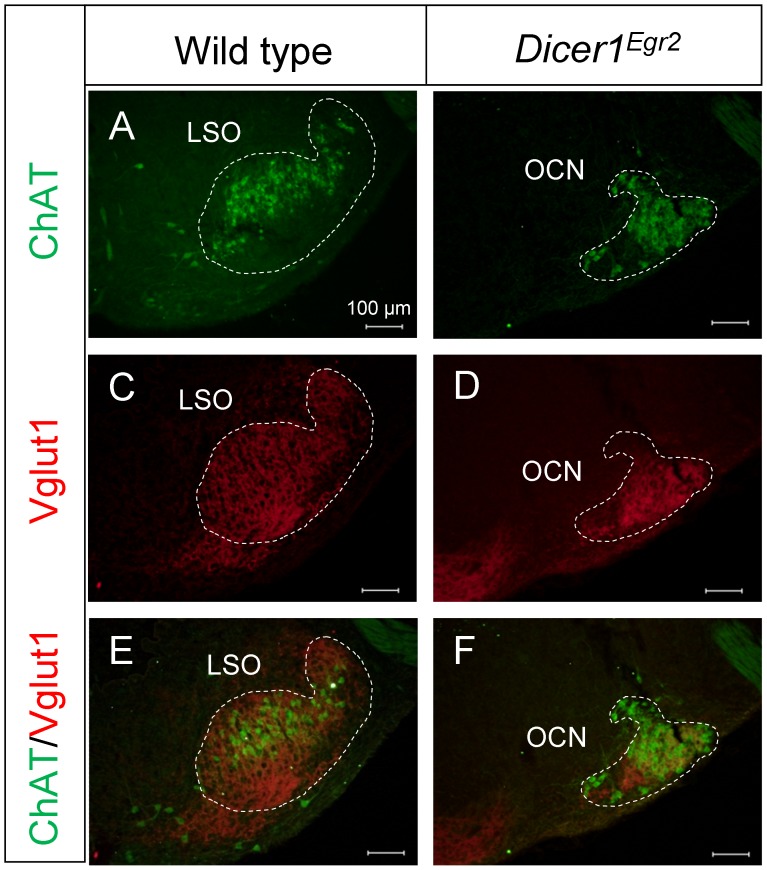

Vglut1 labeling was detected in two ventral areas of the putative SOC region of Dicer1Egr2 animals (Fig. 4B). The ventromedial area likely consists of the pontine grey, as judged from Nissl stained sections. The ventrolateral cell group was observed in 7–8 Nissl stained slices compared to∼19–21 slices containing the LSO in control animals (Fig. 4F). These cells might represent olivocochlear neurons, which are derived from r4 [63] and hence not targeted in Egr2::Cre mice. To determine the identity of this cell group, we performed double labeling experiments using antibodies against Vglut1 and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), a marker of the cholinergic OC neurons [64], [65]. In agreement with previous analyses [64], [66], we observed in wild type animals ChAT positive neurons intermingled with LSO principal neurons (Fig. 5A). Dicer1Egr2 mice also contained ChAT positive neurons, but labeling was confined to a densely packed ventrolateral cell group (Fig. 5B). The same area was also immunoreactive for the presynaptic marker Vglut1 (Fig. 5C–F). This is consistent with the assumption that OC neurons receive the same input as the principal LSO neurons [2]. These data demonstrate that OC neurons are still present in the SOC. Their organization, however, is altered, likely due to disrupted SOC formation. Together these results reveal a lack of principal nuclei such as the MNTB and the LSO proper in the SOC of adult Dicer1Egr2 mice.

Figure 5. Presence of the olivocochlear neurons in Dicer1Egr2 mice.

A,B ChAT immunolabeling was detected throughout the LSO of wild type mice (A), whereas in Dicer1Egr2 mice, ChAT positive cells were restricted to a densely packed ventrolateral cell group (B). (C–F) The same SOC area was labeled by Vglut1, as revealed in the overlay (E–F). Two animals aged P15–P20 were analyzed per genotype. LSO, lateral superior olive; OCN, olivocochlear neurons. Dorsal is up, lateral is to the right.

To analyze whether the absence of large parts of the SOC was caused by disrupted histogenesis or was secondary to the malformation of the CNC, we examined P0 Dicer1Egr2 mice as well. In contrast to wild type animals, only weak Vglut1 labeling was present in knockout animals (Fig. 4G,H). Similar to the SOC of adult Dicer1Egr2 mice, immunoreactivity was restricted to the ventral most part of the SOC. To determine the extent of alterations in the perinatal SOC, Nissl stained sections were analyzed (Fig. 4I,J). Alike adult animals, P0 Dicer1Egr2 mice lacked major nuclei such as the MNTB and the LSO. Only a compact cell group was present in the ventrolateral part, which is in agreement with the presence of OC neurons in the SOC from E13.5 on [63]. This cell group was seen in ∼6 slices, compared to ∼15 slices containing the LSO in wild type animals. Taken together, these results identify a crucial role of Dicer for formation of the SOC.

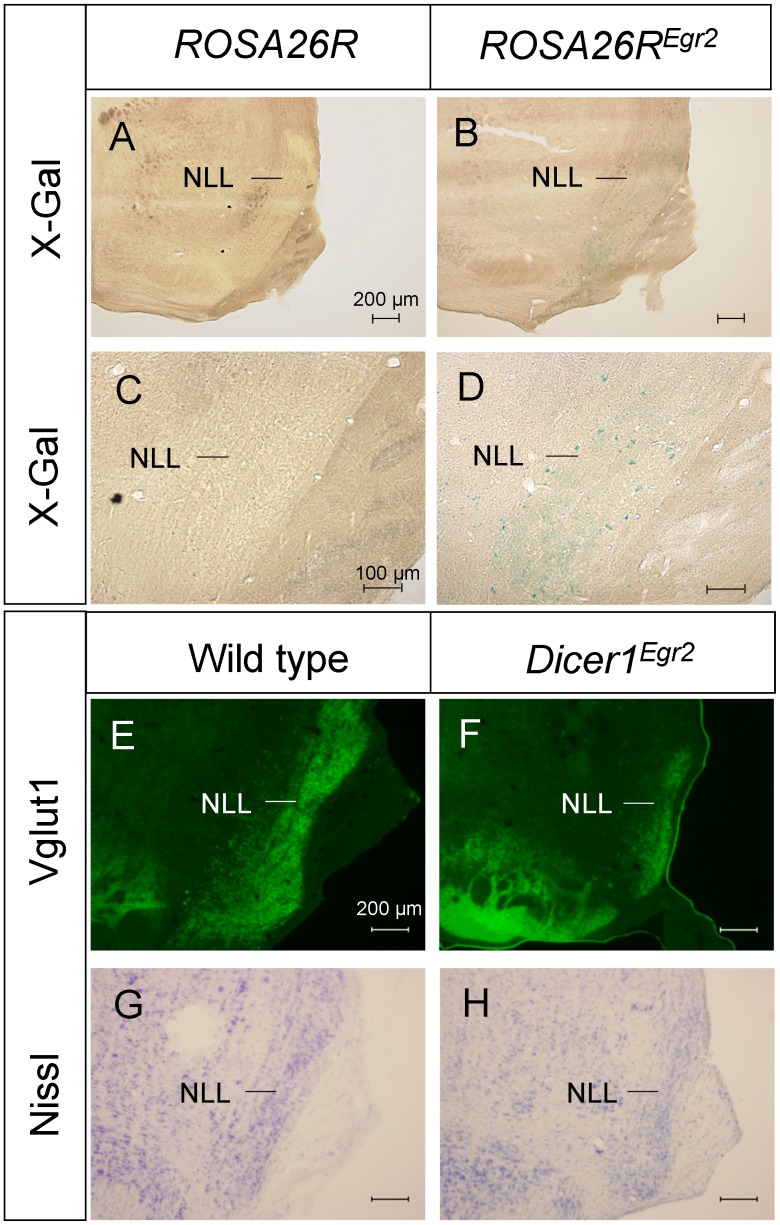

Secondary Effects of Egr2-Cre-mediated Loss of Dicer1 in the Nuclei of Lateral Lemniscus

In the ascending auditory pathway, the CNC and SOC project to nuclei of the lateral lemniscus (NLL) [1], [2]. The embryological origin of this auditory center is unknown. Analysis of Egr2::Cre mouse paired to ROSA26R mice revealed only very few β-galactosidase positive cells in the NLL (Fig. 6A–D). These data reveal that most of the neurons are not descendent from Egr2 positive cells. To investigate whether disruption of the CNC and SOC causes secondary disruption of this center, Vglut1 immunohistochemistry was performed. Vglut1 stained the NLL in control animals and Dicer1Egr2 mice. In the latter, however, the NLL appeared smaller in size (Fig. 6E,F). To determine whether this was reflecting reduced Vglut1 positive projections from the CNC and SOC or true reduction in size, we additionally performed Nissl staining. This analysis revealed that the NLL was smaller in Dicer1Egr2 mice (Fig. 6G,H). Since this reduction is likely caused by the lack of appropriate innervation from CNC and SOC neurons and not due to a lack of Dicer1 in the NLL, a detailed quantitative analysis was not performed.

Figure 6. Reduced size of the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus is attributable to secondary effects of Dicer1 loss.

A–D, Egr2::Cre mice were crossed with ROSA26R mice, resulting in expression of β-galactosidase after Cre-mediated recombination. Only few X-gal positive cells were detected in the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus in the overview (A,B) or at high magnification (C,D). E,F, Vglut1 labeling of the nuclei of the lateral lemniscus in adult (P29, 2 animals per genotype) wild type (E) or Dicer1Egr2 mice (F) revealed reduced size of the nuclei in Dicer1Egr2 mice. G,H, Diminished size of the nuclei in Dicer1Egr2 mice (H) was confirmed by Nissl staining (P29, 2 animals per genotype) (G). NLL, nuclei of the lateral lemniscus. Dorsal is up, lateral is to the right.

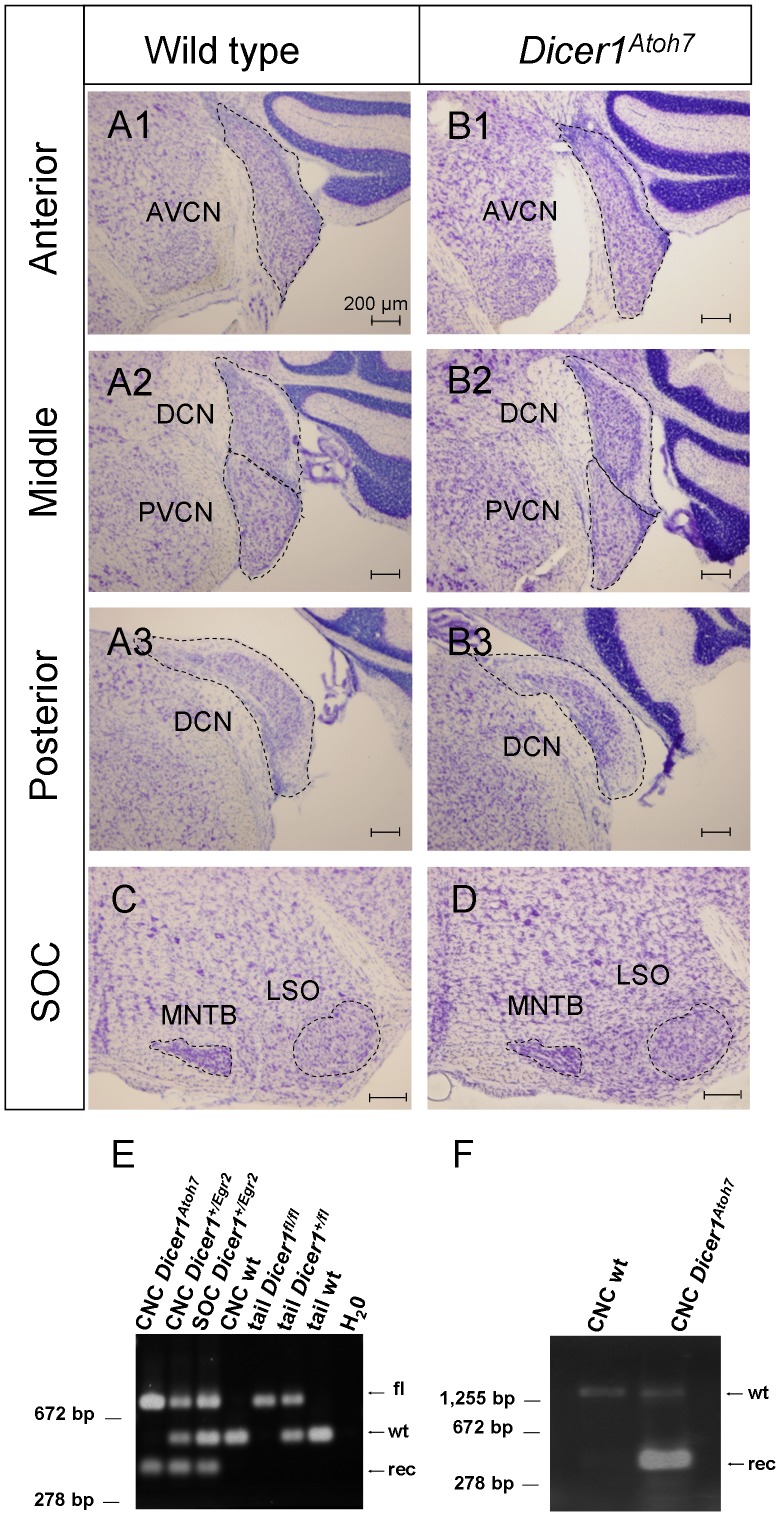

No Macroscopic Alteration of the CNC in Dicer1Atoh7

The data obtained so far indicate an essential role of Dicer during histogenesis of the auditory brainstem. Egr2::Cre mediates recombination as early as the six-somite stage which is around embryonic day (E) 8 [67], [68]. This early time point precedes the birth date of most auditory brainstem neurons, which is between E9 and E15 [69], [70]. To narrow down the critical period of Dicer action during histogenesis of the auditory brainstem, we wished to ablate Dicer1 at a later embryonic time point. Since no inducible Egr2::Cre mouse line is yet available, we employed an Atoh7::Cre mouse line (aka Math5::Cre) [52]. On partnering with a reporter mouse line, recombination is observed from E12.5 onwards in bushy cells of the VCN with peak expression at E17 [71]. Since bushy cells represent >90% of all neurons in the VCN [72], we analyzed formation of the VCN in Atoh7::Cre;Dicer1fl/fl (Dicer1Atoh7 in the following) by Nissl staining of coronal sections in adult animals. In contrast to Dicer1Egr2, no qualitative evidence for volume reduction was observed in the AVCN or PVCN or the neighboring DCN in Dicer1Atoh7 animals (Fig. 7A,B). In agreement with normal formation of the CNC, the SOC had normal size and organization, as judged from Nissl stained sections (Fig. 7C,D).

Figure 7. Normal CNC in adult Dicer1Atoh7 mice. A,B,

Nissl stained CNC sections of adult (P42, 3 animals) wild type (A) or Dicer1Atoh7 mice (P42, 3 animals) (B) at anterior (A1,B1), middle (A2,B2) or posterior (A3,B3) levels. No difference in shape or size was observed between wild type and Dicer1Atoh7 mice. C,D, Nissl stained sections revealed normal formation of the SOC in Dicer1Atoh7 mice. E, Genotyping PCR of DNA extracted from the CNC of indicated mouse lines. In homozygous Dicer1Atoh7 mice, two alleles were present: 429 bp (recombined allele) and 767 bp (floxed allele), whereas in the CNC of wild type mice, a 560 bp fragment was amplified corresponding to the wild type allele. F, RT-PCR analysis of mRNA extracted from the CNC of a wild type or Dicer1Atoh7 mouse. In wild type, only the full length sequence (1,500 bp) was amplified, whereas in Dicer1Atoh7 mice, also the truncated sequence (360 bp) was amplified. Data are representative examples of 2 to 3 biologically independent experiments. These data confirm Cre-mediated recombination in the AVCN. fl, floxed allele; rec, allele after Cre-mediated recombination; wt, wild type allele.

Atoh7 shows low expression in the auditory brainstem compared to the retina [71]. Since recombination requires four Cre molecules acting simultaneously [73], high concentrations of the enzyme are required for loxP-mediated recombination [74]. We therefore analyzed whether genetic recombination had occurred in Dicer1Atoh7 animals. Since no antibody is available to specifically detect truncated Dicer protein after recombination, we probed recombination on the genomic and RNA level. Genotyping PCR on DNA isolated from the CNC provided the expected products of 429 bp (recombined allele) and 767 bp (floxed allele) in Dicer1Atoh7 mice, similar to Dicer1Egr2 mice (Fig. 7E). Both products were lacking in the CNC of wild type mice, which displayed a product of 560 bp (Fig. 7E). In addition, RT-PCR on RNA from the CNC of Dicer1Atoh7 mice yielded two products. One cDNA product was of the expected size of 1,500 bp, corresponding to the wild type Dicer1 allele, and a second product was 360 bp in length, reflecting the deletion of exons 23 and 24 in the recombined allele (Fig. 7F). The shorter cDNA was not observed in control animals (Fig. 7F). These results demonstrate successful recombination in Dicer1Atoh7 mice. The normal structure of the CNC in this mouse line therefore suggests a critical window of Dicer action during embryonic development of the CNC. The precise time window for the action of miRNAs, however, remains to be determined as a delayed disappearance of miRNAs has been reported after loss of Dicer [37], [45], [75].

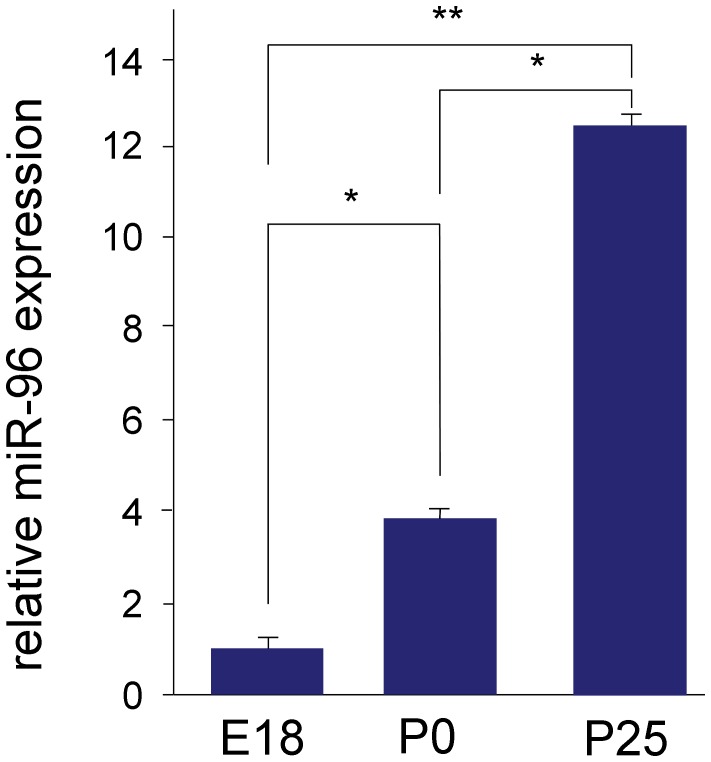

Expression of miR-96 in the Brainstem

In the cochlea, miR-96 is required for proper perinatal development of the cochlea. We recently demonstrated an essential retrocochlear function of the peripheral deafness gene Cacna1d for the development of the auditory brainstem [76]. To analyse whether a reotrocochlear role holds also true for miR-96, we determined its expression in the developing brainstem. Quantitative real time-PCR experiments revealed low expression at E18, but up-regulation thereafter. At P0 miR-96 expression increased by 4 fold compared to E18, and at P25 expression increased by 12 fold compared to E18 (Fig. 8). These data suggest a role of miR-96 in postnatal maturation processes of the auditory brainstem but not during histogenesis. Other miRNAs are therefore likely required for proper formation of the auditory brainstem.

Figure 8. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of miR-96 in mouse brainstem.

qRT-PCR analysis reveals that expression of miR-96 increases in the mouse brainstem with age, when comparing E18, P0 and P25. At least 3 biological repeats were done in triplicates (t-test,* P<0.05, ** P<0.01).

Discussion

Embryonic Requirement of Dicer for Histogenesis of the Auditory Brainstem

Our analysis of two different mouse lines with differentially timed targeted ablation of Dicer uncovered an essential role of this enzyme for development of the auditory brainstem. We observed striking morphological abnormalities in both the CNC and SOC of Dicer1Egr2 mice. The CNC showed a dramatic volume reduction and the principal nuclei of the SOC such as the MNTB and LSO were absent. These abnormalities were already present at birth, demonstrating disrupted histogenesis of the two auditory brainstem structures. An early requirement of Dicer is supported by our observation, that the VCN developed normal in Dicer1Atoh7 mice. Expression of Atoh7 in the murine brainstem starts from E12.5 and peaks at E17, whereas Egr2 is already expressed from E8 onwards. VCN neurons are born in the mouse between E11 and E14 and SOC neurons between E9 and E14 [70]. Thus, Egr2 expression precedes birth of these neurons by several days, whereas the Atoh7 expression pattern rather corresponds with the migration of the neurons to their destination in the auditory brainstem [17], [71]. These data indicate a critical time window for Dicer action in the VCN to a period between E8 and E17 (peak expression of Atoh7 in the VCN). However, recent studies demonstrated also a gap of up to several days between loss of Dicer and miRNA decay [44], [45], [77]. Therefore, the precise time point of miRNA requirement awaits identification of the miRNAs being essential for auditory brainstem development.

A crucial role of Dicer during early embryonic development of central auditory structures is in accord with the lack of the inferior colliculus at E18.5 in mice with Wnt1::Cre mediated ablation of Dicer1 [78]. Furthermore, studies in other neuronal systems such as the neocortex [79], sympathetic neurons [80], forebrain, cerebellum, retina, and ear [37], [44] support a critical role of Dicer during neuronal differentiation [37], [81]. It is therefore likely that the critical time period for SOC neurons, which could not be narrowed down due the lack of suitable Cre-driver lines, is similar to those of other neural populations.

In Dicer1Egr2 mice, the phenotype in the SOC was more dramatic compared to the CNC. Whereas major SOC nuclei such as the MNTB were completely missing, all three major subdivisions of the CNC were present albeit at drastically reduced volumes. Recently, the structural integrity of SOC nuclei was shown to depend on proper formation of the CNC. Disrupted neurogenesis of the AVCN in Atoh1Egr2 mice resulted in increased apoptosis of MNTB neurons, likely due to lack of anterograde trophic support [18]. We consider it unlikely that a similar mechanism contributed to the lack of major SOC nuclei in Dicer1Egr2 mice. In Atoh1Egr2 mice, all SOC nuclei were present at birth and increased apoptosis was noted only postnatally between P0 and P3 [18]. A critical role of innervation in postnatal development is in accord with the observation that neurons of the SOC such as those of the MNTB complete their migration and start to be functionally connected to VCN neurons not earlier than E17 [82], which is only 2 days prior birth (P0 ≈ E19). The absence of major SOC nuclei such as the MNTB or LSO in Dicer1Egr2 mice therefore does not represent secondary loss due to disrupted histogenesis of the CNC. It is rather a direct cause of lack of Dicer1 in these neurons. Our data thereby are also in excellent agreement with the previous notion, that most SOC neurons are derived from r3 and r5 [18].

In Dicer1Egr2 mice, the only recognizable neurons in the SOC were ChAT positive OC neurons. This is in agreement with their embryonic origin in r4 [63]. These neurons are therefore not Dicer-deficient in Dicer1Egr2 mice. Furthermore, OC neurons arrive several days ahead of the other neurons in the SOC area, as they are present as early as E13 [63]. Survival of OC neurons might therefore be independent of the principal SOC neurons. This observation is in accord with an analysis in Atoh1Egr2 mice, which display a reduced volume of the LSO and MNTB. Similar to the situation in Dicer1Egr2 animals, OC neurons were present, but densely packed at the ventral part of the SOC [18].

Candidate miRNAs Required for Histogenesis of the Auditory Brainstem

What might be the underling molecular mechanisms of the observed abnormalities in the auditory brainstem? The main function of Dicer is the generation of miRNA (for a notable exception see [83]). Since miR-96 is required for development of the peripheral auditory system, we considered this miRNA as a candidate for the histogenesis of the central auditory system. We therefore studied its expression during development. Due to the small and obscure structure of the perinatal SOC, we had to limit our qRT-PCR to the entire brainstem. This revealed a postnatal up-regulation, suggesting that this miRNA rather plays a role in maturation processes of the auditory brainstem. However, a final conclusion awaits specific expression analysis in the developing SOC and functional studies in diminuendo mice, as also low expression of miRNAs might have functional consequences. Nevertheless, other miRNA are likely required for the histogenesis of the auditory brainstem. An attractive candidate might be miR-124, an evolutionary conserved miRNA. Its disappearance in various newborn neurons after deletion of Dicer correlates with cell death (44). Another candidate might be the miR-34 family, which was shown to regulate Wnt1 [84], and is predicted to target Atoh1 [85]. Both the Wnt1 lineage and Atoh1 lineage of the rhombic lip densely populate the auditory brainstem [16], [18]. Furthermore, Fgf8, an upstream activator of Atoh1 [86], is regulated by miR-9 [87]. Finally, expression of Hox genes, which are essential for hindbrain organization [88], is also regulated by miRNAs. miR-10 regulates Hoxb1 and Hoxb3 [89]. Hoxb1 descendant cells, which are derived from r4, contribute to the PVCN and DCN, whereas Hoxb3 is expressed in r5 [88], which largely contributes to the DCN [16] and SOC [18]. Future studies have hence to address the role of these miRNAs in histogenesis of auditory brainstem structures.

In summary, our data demonstrate the crucial embryonic dependence of auditory brainstem formation on Dicer activity. This extends the critical role of this enzyme from the peripheral to the central auditory system. Most likely, the observed phenotype is due to lack of miRNAs governing embryonic development of central auditory structures. Their identification will provide important insights into the genetic program of the auditory brainstem. Equally important might be the role of miRNAs during maturation and function of the auditory system, as indicated by the postnatal up-regulation of miR-96 in the brainstem.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anja Feistner and Jasmin Schröder for excellent technical assistance, Christine Köppl for helpful discussion, and Salah El Mestikawy for providing Vglut1 antibody.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the DFG grant NO 428/5-1 and the Israel Science Foundation (grant no. 1320/11). H.H. was supported by a stipend from the PhD program Hearing of the State of Lower Saxony. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Helfert RH, Snead CR, Altschuler RA (1991) The ascending auditory pathways. In: Altschuler RA, editors. Neurobiology of Hearing: The central auditory system. New York: Raven Press. 1–25.

- 2.Malmierca MS, Merchan MA (2004) Auditory system. In: Praxinos G, editor. The rat nervous system. Elsevier. 997–1082.

- 3.Irvine DRF (1986) Progress in Sensory Physiology 7. The Auditory Brainstem. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

- 4. Grothe B (2003) New roles for synaptic inhibition in sound localization. Nat Rev Neurosci 4: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grothe B, Pecka M, Mcalpine D (2010) Mechanisms of sound localization in mammals. Physiol Rev 90: 983–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guinan JJJr (1996) Physiology of olivocochlear efferents. In: Dallos P, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. The cochlea. New York: Springer-Verlag. 435–502.

- 7. Oertel D (1991) The role of intrinsic neuronal properties in the encoding of auditory information in the cochlear nuclei. Curr Opin Neurobiol 1: 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oertel D (1997) Encoding of timing in the brain stem auditory nuclei of vertebrates. Neuron 19: 959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnston J, Forsythe ID, Kopp-Scheinpflug C (2010) Going native: voltage-gated potassium channels controlling neuronal excitability. J Physiol 588: 3187–3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harris JA, Iguchi F, Seidl AH, Lurie DI, Rubel EW (2008) Afferent deprivation elicits a transcriptional response associated with neuronal survival after a critical period in the mouse cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 28: 10990–11002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koehl A, Schmidt N, Rieger A, Pilgram SM, Letunic I, et al. (2004) Gene expression profiling of the rat superior olivary complex using serial analysis of gene expression. Eur J Neurosci 20: 3244–3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nothwang HG, Becker M, Ociepka K, Friauf E (2003) Protein analysis in the rat auditory brainstem by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Mol Brain Res 116: 59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Friedland DR, Popper P, Eernisse R, Cioffi JA (2006) Differentially expressed genes in the rat cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience 142: 753–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kandler K, Clause A, Noh J (2009) Tonotopic reorganization of developing auditory brainstem circuits. Nat Neurosci 12: 711–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friauf E (2004) Developmental changes and cellular plasticity in the superior olivary complex. In: Parks TN, Rubel EW, Fay RR, Popper AN, editors. Plasticity of the auditory system. New York: Springer. 49–95.

- 16. Farago AF, Awatramani RB, Dymecki SM (2006) Assembly of the brainstem cochlear nuclear complex is revealed by intersectional and subtractive genetic fate maps. Neuron 50: 205–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang VY, Rose MF, Zoghbi HY (2005) Math1 expression redefines the rhombic lip derivatives and reveals novel lineages within the brainstem and cerebellum. Neuron 48: 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maricich SM, Xia A, Mathes EL, Wang VY, Oghalai JS, et al. (2009) Atoh1-lineal neurons are required for hearing and for the survival of neurons in the spiral ganglion and brainstem accessory auditory nuclei. J Neurosci 29: 11123–11133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Berezikov E (2011) Evolution of microRNA diversity and regulation in animals. Nat Rev Genet 12: 846–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stefani G, Slack FJ (2008) Small non-coding RNAs in animal development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 219–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ (2001) Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature 409: 363–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bartel DP (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fineberg SK, Kosik KS, Davidson BL (2009) MicroRNAs potentiate neural development. Neuron 64: 303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ (2009) Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136: 642–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, et al. (2004) Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell 117: 69–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu Q, Feng Y, Zhu Z (2009) Dicer-like (DCL) proteins in plants. Funct Integr Genomics 9: 277–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakayashiki H, Kadotani N, Mayama S (2006) Evolution and diversification of RNA silencing proteins in fungi. J Mol Evol 63: 127–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, et al. (2003) Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet 35: 215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ (2005) The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 10898–10903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andl T, Murchison EP, Liu F, Zhang Y, Yunta-Gonzalez M, et al. (2006) The miRNA-processing enzyme dicer is essential for the morphogenesis and maintenance of hair follicles. Curr Biol 16: 1041–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davis TH, Cuellar TL, Koch SM, Barker AJ, Harfe BD, et al. (2008) Conditional loss of Dicer disrupts cellular and tissue morphogenesis in the cortex and hippocampus. J Neurosci 28: 4322–4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li X, Jin P (2010) Roles of small regulatory RNAs in determining neuronal identity. Nat Rev Neurosci 11: 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schratt G (2009) microRNAs at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 842–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pinter R, Hindges R (2010) Perturbations of microRNA function in mouse dicer mutants produce retinal defects and lead to aberrant axon pathfinding at the optic chiasm. PLoS ONE 5: e10021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maiorano NA, Hindges R (2012) Non-Coding RNAs in Retinal Development. Int J Mol Sci 13: 558–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Georgi SA, Reh TA (2010) Dicer is required for the transition from early to late progenitor state in the developing mouse retina. J Neurosci 30: 4048–4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhan S, Merlin C, Boore JL, Reppert SM (2011) The monarch butterfly genome yields insights into long-distance migration. Cell 147: 1171–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Berdnik D, Fan AP, Potter CJ, Luo L (2008) MicroRNA processing pathway regulates olfactory neuron morphogenesis. Curr Biol 18: 1754–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Johnston RJ, Chang S, Etchberger JF, Ortiz CO, Hobert O (2005) MicroRNAs acting in a double-negative feedback loop to control a neuronal cell fate decision. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 12449–12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kapsimali M, Kaushik AL, Gibon G, Dirian L, Ernest S, et al. (2011) Fgf signaling controls pharyngeal taste bud formation through miR-200 and Delta-Notch activity. Development 138: 3473–3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cayirlioglu P, Kadow IG, Zhan X, Okamura K, Suh GS, et al. (2008) Hybrid neurons in a microRNA mutant are putative evolutionary intermediates in insect CO2 sensory systems. Science 319: 1256–1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhao J, Lee MC, Momin A, Cendan CM, Shepherd ST, et al. (2010) Small RNAs control sodium channel expression, nociceptor excitability, and pain thresholds. J Neurosci 30: 10860–10871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kersigo J, D'Angelo A, Gray BD, Soukup GA, Fritzsch B (2011) The role of sensory organs and the forebrain for the development of the craniofacial shape as revealed by Foxg1-cre-mediated microRNA loss. Genesis 49: 326–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Soukup GA, Fritzsch B, Pierce ML, Weston MD, Jahan I, et al. (2009) Residual microRNA expression dictates the extent of inner ear development in conditional Dicer knockout mice. Dev Biol 328: 328–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Friedman LM, Dror AA, Mor E, Tenne T, Toren G, et al. (2009) MicroRNAs are essential for development and function of inner ear hair cells in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 7915–7920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mencia A, Modamio-Hoybjor S, Redshaw N, Morin M, Mayo-Merino F, et al. (2009) Mutations in the seed region of human miR-96 are responsible for nonsyndromic progressive hearing loss. Nat Genet 41: 609–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lewis MA, Quint E, Glazier AM, Fuchs H, de Angelis MH, et al. (2009) An ENU-induced mutation of miR-96 associated with progressive hearing loss in mice. Nat Genet 41: 614–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kuhn S, Johnson SL, Furness DN, Chen J, Ingham N, et al. (2011) miR-96 regulates the progression of differentiation in mammalian cochlear inner and outer hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 2355–2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Soriano P (1999) Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21: 70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Voiculescu O, Charnay P, Schneider-Maunoury S (2000) Expression pattern of a Krox-20/Cre knock-in allele in the developing hindbrain, bones, and peripheral nervous system. Genesis 26: 123–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang Z, Ding K, Pan L, Deng M, Gan L (2003) Math5 determines the competence state of retinal ganglion cell progenitors. Dev Biol 264: 240–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, et al. (2001) The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci 21: RC181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chomczynski P, Sacchi N (1987) Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem 162: 156–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Champagnat J, Morin-Surun MP, Bouvier J, Thoby-Brisson M, Fortin G (2011) Prenatal development of central rhythm generation. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 178: 146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Champagnat J, Morin-Surun MP, Fortin G, Thoby-Brisson M (2009) Developmental basis of the rostro-caudal organization of the brainstem respiratory rhythm generator. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364: 2469–2476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhou J, Nannapaneni N, Shore S (2007) Vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 are differentially associated with auditory nerve and spinal trigeminal inputs to the cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 500: 777–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mugnaini E, Osen KK, Dahl AL, Friedrich VL Jr, Korte G (1980) Fine structure of granule cells and related interneurons (termed Golgi cells) in the cochlear nuclear complex of cat, rat and mouse. J Neurocytol 9: 537–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Mugnaini E, Warr WB, Osen KK (1980) Distribution and light microscopic features of granule cells in the cochlear nuclei of cat, rat, and mouse. J Comp Neurol 191: 581–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ryugo DK, Haenggeli CA, Doucet JR (2003) Multimodal inputs to the granule cell domain of the cochlear nucleus. Exp Brain Res 153: 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Blaesse P, Ehrhardt S, Friauf E, Nothwang HG (2005) Developmental pattern of three vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat superior olivary complex. Cell Tissue Res 320: 33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Friauf E (1993) Transient appearance of calbindin-D28k-positive neurons in the superior olivary complex of developing rats. J Comp Neurol 334: 59–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Karis A, Pata I, van Doorninck JH, Grosveld F, de Zeeuw CI, et al. (2001) Transcription factor GATA-3 alters pathway selection of olivocochlear neurons and affects morphogenesis of the ear. J Comp Neurol 429: 615–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Simmons DD (2002) Development of the inner ear efferent system across vertebrate species. J Neurobiol 53: 228–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Simmons DD, Duncan J, de Caprona DC, Fritzsch B (2011) Development of the Inner Ear Efferent System. In: Ryugo DK, Fay RR, editors. Auditory and Vestibular Efferents. New York: Springer. 187–216.

- 66. White JS, Warr WB (1983) The dual origins of the olivocochlear bundle in the albino rat. J Comp Neurol 219: 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Voiculescu O, Taillebourg E, Pujades C, Kress C, Buart S, et al. (2001) Hindbrain patterning: Krox20 couples segmentation and specification of regional identity. Development 128: 4967–4978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Theiler K (1989) The House Mouse: Atlas of Embryonic Development. New York: Springer Verlag.

- 69. Martin MR, Rickets C (1981) Histogenesis of the cochlear nucleus of the mouse. J Comp Neurol 197: 169–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Taber Pierce E (1973) Time of origin of neurons in the brain stem of the mouse. Prog Brain Res 40: 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Saul SM, Brzezinski JA, Altschuler RA, Shore SE, Rudolph DD, et al. (2008) Math5 expression and function in the central auditory system. Mol Cell Neurosci 37: 153–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Trune DR (1982) Influence of neonatal cochlear removal on the development of mouse cochlear nucleus: I. Number, size, and density of its neurons. J Comp Neurol 209: 409–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mack A, Sauer B, Abremski K, Hoess R (1992) Stoichiometry of the Cre recombinase bound to the lox recombining site. Nucleic Acids Res 20: 4451–4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hamilton DL, Abremski K (1984) Site-specific recombination by the bacteriophage P1 lox-Cre system. Cre-mediated synapsis of two lox sites. J Mol Biol 178: 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Weston MD, Pierce ML, Jensen-Smith HC, Fritzsch B, Rocha-Sanchez S, et al. (2011) MicroRNA-183 family expression in hair cell development and requirement of microRNAs for hair cell maintenance and survival. Dev Dyn 240: 808–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Satheesh SV, Kunert K, Ruttiger L, Zuccotti A, Schonig K, et al. (2012) Retrocochlear function of the peripheral deafness gene Cacna1d. Hum Mol Genet. 21: 3896–3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Schaefer A, O'Carroll D, Tan CL, Hillman D, Sugimori M, et al. (2007) Cerebellar neurodegeneration in the absence of microRNAs. J Exp Med 204: 1553–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Huang T, Liu Y, Huang M, Zhao X, Cheng L (2010) Wnt1-cre-mediated conditional loss of Dicer results in malformation of the midbrain and cerebellum and failure of neural crest and dopaminergic differentiation in mice. J Mol Cell Biol 2: 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. De Pietri TD, Pulvers JN, Haffner C, Murchison EP, Hannon GJ, et al. (2008) miRNAs are essential for survival and differentiation of newborn neurons but not for expansion of neural progenitors during early neurogenesis in the mouse embryonic neocortex. Development 135: 3911–3921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zehir A, Hua LL, Maska EL, Morikawa Y, Cserjesi P (2010) Dicer is required for survival of differentiating neural crest cells. Dev Biol 340: 459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shi Y, Zhao X, Hsieh J, Wichterle H, Impey S, et al. (2010) MicroRNA regulation of neural stem cells and neurogenesis. J Neurosci 30: 14931–14936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hoffpauir BK, Kolson DR, Mathers PH, Spirou GA (2010) Maturation of synaptic partners: functional phenotype and synaptic organization tuned in synchrony. J Physiol 588: 4365–4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kaneko H, Dridi S, Tarallo V, Gelfand BD, Fowler BJ, et al. (2011) DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature 471: 325–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hashimi ST, Fulcher JA, Chang MH, Gov L, Wang S, et al. (2009) MicroRNA profiling identifies miR-34a and miR-21 and their target genes JAG1 and WNT1 in the coordinate regulation of dendritic cell differentiation. Blood 114: 404–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Nakamura T, Yamashita T, Saitoh N, Takahashi T (2008) Developmental changes in calcium/calmodulin-dependent inactivation of calcium currents at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol 586: 2253–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Millimaki BB, Sweet EM, Dhason MS, Riley BB (2007) Zebrafish atoh1 genes: classic proneural activity in the inner ear and regulation by Fgf and Notch. Development 134: 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Leucht C, Stigloher C, Wizenmann A, Klafke R, Folchert A, et al. (2008) MicroRNA-9 directs late organizer activity of the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Nat Neurosci 11: 641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tumpel S, Wiedemann LM, Krumlauf R (2009) Hox genes and segmentation of the vertebrate hindbrain. Curr Top Dev Biol 88: 103–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Woltering JM, Durston AJ (2008) MiR-10 represses HoxB1a and HoxB3a in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 3: e1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]