Abstract

Beside their genomic mode of action, estrogens also activate a variety of cellular signaling pathways through non-genomic mechanisms. Until recently, little was known regarding the functional significance of such actions in males and the mechanism that control local estrogen concentration with a spatial and time resolution compatible with these non-genomic actions had rarely been examined. Here, we review evidence that estrogens rapidly modulate a variety of behaviors in male vertebrates. Then, we present in vitro work supporting the existence of a control mechanism of local brain estrogen synthesis by aromatase along with in vivo evidence that rapid changes in aromatase activity also occur in a region-specific manner in response to changes in the social or environmental context. Finally, we suggest that the brain estrogen provision may also play a significant role in females. Together these data bolster the hypothesis that brain-derived estrogens should be considered as neuromodulators.

Keywords: aromatase, estrogen receptors, non-genomic effects, male behavior

1. Introduction

Estrogens, such as 17β-estradiol (E2), profoundly alter a wide array of physiological and behavioral processes including gonadotropin secretion, social behaviors, nociception and cognition [164]. The effects of estrogens are often mediated via binding to their cognate nuclear receptors, the estrogen receptors alpha and beta (ERα and ERβ), that activate a chain of intracellular events leading to transcriptional regulation of target genes [42; 274]. To our knowledge, the fastest changes in protein concentration are observed for immediate early genes. New messenger RNA and protein product of these genes are detected within 5 min and 1 hour respectively [48]. To produce functional responses, most proteins have to undergo post-translational modifications and translocate to their site of action (e.g. acquire enzymatic activity, be integrated in functional complexes at the membrane or synapse). As a result these processes requiring protein synthesis usually develop slowly (hours-days) and produce enduring effects associated with the changes in circulating concentrations of gonadal steroids typical of specific physiological states (e.g. stages of the estrus cycle or the breeding cycle) [83; 278]. Genomic effects of estrogens on behavior are often ultimately mediated by changes in the production or action of neurotransmitters in specific brain circuits resulting for a modification of the transcription and translation of enzymes that synthesize or catabolize the transmitters or of their receptors [80].

Besides these genomic effects, estrogens can also act on membrane-associated receptors to activate multiple cellular processes that do not depend on the synthesis of new proteins. These non-genomic cellular actions occur in a much shorter time scale than previously anticipated (seconds/minutes) [55; 157]. Such effects have been documented in numerous cell types including tumor cells ([10; 26; 41; 107; 132; 181; 210]; For review see, [146; 182; 268]). Considering neuronal preparations specifically, acute changes in estrogens’ concentration alter numerous intracellular events in vitro including the modulation of intracellular calcium concentrations [1; 28; 168] or of cyclic AMP [105; 174] and protein phosphorylation [179; 281; 283]. In turn, these activated signaling cascades can lead to modulations of the coupling state of a neurotransmitter receptor with its effector system [139; 144; 175; 176; 177], of enzymatic activities [198; 205], of neurophysiological activity [124; 126; 179; 292] or finally to indirect transcriptional activation through the phosphorylation of transcription factors such as cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) [2; 3; 33; 295] in specific brain regions. It is thus not surprising that evidence is emerging in support of a role for estrogens in the acute modulation of physiological and behavioral responses in vivo [59; 224].

Although prolonged exposure to estrogens can induce non-genomic signaling, the recent demonstration that membrane initiated effects in neurons desensitize relatively rapidly ([32; 78; 79; 101]; reviewed in [170; 172]) suggests that mechanisms must exist to regulate estrogen concentration on much shorter time scales. Unfortunately, the question of the source of these rapid changes in estrogen concentration is rarely considered. Acute effects of estrogens on cellular, physiological or behavioral processes have been described in both sexes. The ovaries constitute the major source of estrogens in females which fluctuate relatively rapidly during the estrus cycle and could thus trigger rapid non-genomic actions of this steroid ([8; 35; 117; 254; 262; 285]; for review see [172; 278]; but see [55] for a critical discussion of the time course of fluctuations in gonadal secretions).

Although they circulate at much lower concentrations, estrogens also control many physiological and behavioral responses in males, sometimes in an acute manner. These estrogenic effects depend on the neuronal aromatization of androgens into estrogens [12; 87; 158; 235; 241; 269]. Androgen aromatization is a complex enzymatic reaction that plays a key limiting role for the organization (sexual differentiation) and/or activation of many neural or behavioral processes in vertebrates. Research on the control of local estrogen synthesis by brain aromatase has largely focused on changes in enzyme availability taking place over relatively long time periods following developmental or seasonal changes in circulating steroid concentrations [50; 109; 115; 201; 236; 245]. However, studies taking advantage of the high concentrations of the aromatase protein in the avian brain have recently uncovered a novel mechanism acutely regulating brain estrogen synthesis and thus offering a time resolution for changes in local concentration compatible with the rapid and transient effects of estrogens described in vitro and in vivo. Here, we will first review evidence that estrogens rapidly and reversibly modulate behavior in male vertebrates. Then, we will discuss the mechanisms that control local brain estrogen concentration and their functional significance in vivo. Finally, we will suggest that the local tissue-specific provision of estrogens might not be a male specific characteristic but may also play a significant role in the physiology of females.

2. Rapid behavioral effects of estrogens in males

Rapid effects of estrogens suggesting an action that is independent of the transcriptional activity of liganded nuclear estrogen receptors have now been reported in a variety of animal species in relation with the control of multiple aspects of behavior. The short latency of these effects has originally led to the assumption that they relied on non-genomic mechanisms. However, independent evidence has in many cases been collected in support of this interpretation. Many of these effects indeed appear to be initiated at the cell membrane and/or are blocked by inhibitors of intracellular signaling pathways. In the following, we shall thus qualify the presumptive non-genomic effects of estrogens as rapid if this is the only criterion that has been formally demonstrated. The qualification of non-genomic will be limited to effects for which additional information is available.

Studies of the rapid effects of estrogens can be subdivided in 5 main classes according to the dependent behavioral variable that is measured (see table 1).

Table 1. Summary table of the behaviors acutely modulated by estrogens.

The latency reflects when the effect is detected with regard to the timing of injection, while the duration reflects how long the effect lasts from initiation to disappearance. Note that, since this review focuses on males, this table summarizes mostly the results of studies conducted on males. However, when no data were available on males, work on females was added when providing useful information in the present context.

| Reference | Behavior | Species | Sex | Injection mode (brain region) |

Agonist (doses) | Effect | Latency | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayden-Hixson & Ferris, 1991 [113] |

Agonistic | Hamster | M (GDI) | Central -AH | E2 - 27pg | ↑ flank marking | 15 min | - |

| Trainor et al., 2007 [270] | Aggressive | Beach mice | M (CX+T+ FAD) |

Peripheral (SC) | E2 (75µg/kg) | ↑ attacks | 15 min | - |

| Trainor et al., 2008 [271] | Aggressive | California mice | M (CX+T+ FAD) |

Peripheral (SC) | E2 (100µg/kg) | ↑ bites ↓ attack lat. |

15 min 15 min |

- - |

| Cross & Roselli, 1999 [63] | Sexual | Rat (Sprague Dawley) |

M (CX) | Peripheral (IP) | T � 2–10 mg/kg* E2 -100µg/kg* |

No effect ↑ AGI ↑ mouting |

- 15 min 15 min |

- - - |

| Huddleston et al. 2007 [119] | Sexual | Rat (Sprague Dawley) |

M (CX+DHT) |

Central -MPOA | E2-implant E2-BSA -implant |

↑ copulation ↑ copulation |

48h 48h |

- - |

| Cornil et al., 2006 [56] | Sexual | Quail | M (CX+low T) |

Peripheral (IP) |

E2-500 µg/kg* | ↑ copulation | 15 min | 15 min |

| Cornil et al., 2006 [57] | Sexual | Quail | M (GDI or CX+T) |

Peripheral (IP) | VOR -30 mg/kg* ATD -150 mg/kg* |

↓ motivation ↓ Copulation ↓ motivation ↓ Copulation |

30 min 30 min 30 min 30 min |

30 min 30 min 30 min 30 min |

| Taziaux et al., 2007 [264] | Sexual | Mouse (C57BL/6J) |

M (GDI) | Peripheral (IP) | VOR -1mg/subject VOR + E2500µg ATD -4 mg/subject ATD + E2500µg |

↓ copulation restore behav. ↓ AGI ↓ copulation restore behav |

10 min 10 min 10 min 10 min 10 min |

- - - - - |

| Seredynski et al., 2012 [248] | Sexual | Quail | M (CX+T) CX+T+VOR |

Central -ICV | VOR 50µg* VOR + E2 50µg* VOR + E2-biotin 50µg ATD 50µg ATD + E250µg E2 - 50–100µg* E2-BSA 50µg |

↓ copulation restores behav restores behav ↓ copulation restores behav ↑ motivation ↑ motivation |

30 min 15 min 15 min 30 min 15 min 15 min 15 min |

- - - - - - - |

| Lord et al., 2009 [153] | Sexual | Goldfish | M (GDI) | Peripheral -IP | E2 -100µg/kg T -100µg/kg FAD -12mg/kg |

↑ approach ↑ approach blocks T effect |

10 min 30 min 30 min |

35 min- - - |

| Mangiamele and Thompson, 2012 [13] |

Sperm release | Goldfish | M (GDI) | Peripheral -IP | DES -5µg/subject T -3µg/subject FAD -480 µg/subject |

↑ milt volume | 1 hour | - |

| Remage-Healey and Bass 2004 [214] |

Fictive vocaliz. | Midshipman fish | M (type I †; GDI) |

Peripheral -IM | E2 -1.0 mg/kg | ↑ duration | 5 min | 20 min |

| Remage-Healey and Bass 2007 [215] |

Fictive vocaliz. | Midshipman fish | M (type II †; GDI) & F |

Peripheral -IM | E2 - 0.02 & 0.002 mg/kg* |

↑ duration | 5 min | 40 min |

| Tremere et al. 2009 [272] | Song-evoked spiking activity |

Zebra finches (awake and restraint) |

M&F (GDI) | intracerebral-NCM | E2 -200 ng TMX -5.6 ng ATD -2.8 ng |

↑ firing rate ↓ firing rate ↓ firing rate |

5 min 5 min 5 min |

- - - |

| Tremere et al. 2011 [273] | Song-evoked activity Auditory coding Behavioral pref. |

Zebra finches (awake and restraint) Freely moving |

M (GDI) | intracerebral-NCM intracerebral-NCM intracerebral-NCM |

E2 -3 ng ICI -6 ng TMX -5.4 ng FAD -2.6 ng ATD -2.8 ng E2 -3 ng ICI -6 ng TMX -5.4 ng FAD -2.6 ng ATD -2.8 ng ICI -30 ng TMX -26.8 ng FAD -13 ng ATD -14 ng |

↑ firing rate ↓ firing rate ↓ firing rate ↓ firing rate ↓ firing rate ↑ discrim. ↓ discrim. ↓ discrim. ↓ discrim. ↓ discrim. X pref. for TUT X pref. for TUT X pref. for TUT X pref. for TUT |

5 min 5 min 5 min 30 min 30 min 5 min 5 min 5 min 30 min 30 min 30 min 30 min 30 min 30 min |

2h 2h 2h 2h 2h 2h 2h 2h 2h 2h - - - - |

| Remage-Healey et al. 2010 [219] | Behavioral pref. Auditory processing |

ZB (free moving) ZB anesthetized |

M (GDI) M (GDI) |

Retrodialysis - NCM Retrodialysis - NCM |

FAD .100µM E2 - 30µg/ml (30min) FAD - 100 µM (30min) |

↓ pref for BOS ↑ pref for CON ↓ pref for CON |

30 min 30 min 30 min |

- 30 min 30 min |

| Remage-Healey et al., 2012 [221] | Auditory processing | Zebra finches | F (GDI) | Retrodialysis - NCM | E2 30µg/ml E2 -biotin 60 µg/ml FAD 100µM |

↑ discrim. ↑ discrim. ↓ discrim. |

<30min <30min <30min |

<30min |

| Van Hartesveldt et al., 1989 [275] | Dorsal immobility | Rat (Long evans hooded) |

M&F (GNX) | Central - Striatum | E2-implant 17a- E2-implant |

↑ response ↑ response |

4 h 4 h |

- - |

| Van Hartesveldt et al., 1990 [276] | Dorsal immobility | Rat (Long evans hooded) |

M (GNX) | Central -Striatum | E2 -implant T -implant |

↑ response no effect |

4 h 4 h |

- - |

| Evrard and Balthazart, 2004 [85] | Nociception | Quail | M (CX, CX+T, CX+ E2) (GNX) |

Peripheral (IP) Central (IT) |

VOR -4.8 mg/kg E2 -4.4 mg/kg VOR -15µg ATD -15µg VOR+ E2 -4µg |

↑ FWL ↓ FWL ↑ FWL ↑ FWL ↓ FWL |

20 min 20 min 1 min 1 min 1 min |

- - <25min <25min <25min |

| Liu et al. 2011 [150] | Nociception | Rat (Sprague Dawley) |

F | Central (IT) | FAD -2pg ICI .1.8 pg |

↑ tail-flick lat. ↑ tail-flick lat. |

15 min 30 min |

45 min 30 min |

| Kuhn et al., 2008 [138] | Nociception | Rat (Sprague Dawley) |

M (GDI) | Peripheral (SC) -hind paw |

G1 -100 ng ICI -100 ng |

paw removal paw removal |

30 min 30 min |

- - |

| Packard et al. 1996 [194] | Learning | Rat (Long evans) | M (GDI) | Central -Hp | E2 -1µg | ↑ SM | few min | < 2h |

| Packard and Teather, 2007 [195] | Learning | Rat (Long evans) | F (OVX) | Peripheral - IP | E2 - .0.2 mg/kg | ↑ SM | few min | < 2h |

| Packard and Teather, 2007 [196] | Learning | Rat (Long evans) | F (OVX) | Central - Hp | E2 - 5µg | ↑ SM | few min | < 2h |

| Liu et al., 2008 [148] | Spatial Memory | Mice (C57/Bl6N)/rat (Long evans) |

F (OVX) M (GDI) |

Peripheral (SC) | E2 - 5µg WAY-200070 -10mg/kg WAY-202779 -10mg/kg PPT -10mg/kg |

↑ pCREB in Hp ↑ learning ↑ pCREB in Hp ↑ learning ↑ pCREB in Hp No effect |

15 min > 1day 15 min > 1day 15 min - |

2h - 2h - 2h - |

| Luine et al 2003 [155] | Learning | Rat (Sprague Dawley) |

F (OVX) | Peripheral (SC) | 17bE2 - 15 µg/kg 17a-E2 - 15 µg/kg DES - 15 µg/kg 16a-iodo-E2- 15µg/kg |

↑ OR ↑ OP ↑ OR ↑ OP ↑ OR ↑ OP ↑ OR OP no effect |

30 min <3 min 30 min 30 min <3 min 30 min <3 min |

- <2h - - <2h - - |

| Inagaki et al 2010 [121] | Learning | Rat (Sprague dawley) |

F (GNX) | Peripheral (SC) | 17bE2 - 15–20 µg/kg* 17bE2 - 5–10 µg/kg* 17a-E2 - 5 µg/kg* 17a-E2 - 1–2 µg/kg* |

↑ OP ↑ OR ↑ OP ↑ OR |

<3 min <3 min <3 min <3 min |

<45 min - - - |

| Fernandez et al., 2008 [88] | Learning | Mice (C57BL/6J) | F (OVX) | Peripheral - IP Central - Hp |

E2 - 0.2 mg/kg E2 (IP) + U0126 1µg E2 - 5µg E2-BSA - 5µg E2-BSA + U0126 1µg |

↑ OR X E2 effect ↑ OR ↑ OR X E2-BSA effect |

- - <3h - - |

- - <3h - - |

| Phan et al., 2011 [204] | Learning | Mice (CD1) | F (OVX) | Peripheral - SC | PPT - 50–75 µg* DPN - 30–150 µg* |

↑ SR, OR, OP No effect |

<40min | - |

AEA, auditory evoked activity; AGI, anogenital investigations; AH: anterior hypothalamus; ATD, androstatrienediol (aromatase inhibitor); BOS, bird’s own song; CON, conspecific song; CX, castrated; DES, diethylstilbestrol; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; Discrimi., stimulus discrimination; DPN, 2,3-bis(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile (ERβ specific agonist); E2, 17β-estradiol; E2-BSA, estradiol conjugated to bovine serum albumine; FAD, fadrozole (aromatase inhibitor); Fictive vocaliz., fictive vocalizations; FWL, foot withdrawal latency (from a hot water bath); GDI, gonadally intact; GNX, gonadectomized; Hp, hippocampus; ICI, ICI 182,780 (fulvestrant; general estrogen receptor antagonist); ICV, intracerebroventricular; IM, intramuscular injection; IP; intraperitoneal injection; IT, intrathecal; Lat., latency; MPOA, medial preoptic area; NCM, caudomedial nidopallium; OP, object placement; OR, object recognition; OVX, ovariectomizd; PPt, 4,4’,4”-(4-Propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl) trisphenol (ERα specific agonist); Pref., preference; REV, reversed conspecific song; SC, subcutaneous injection; SM, spatial memory; SR, social recognition; T, testosterone; TMX, tamoxifen (selective estrogen receptor modulator); TUT, tutor song; U0126, MEK inhibitor; Vocaliz., Vocalization; Vor, vorozole (aromatase inhibitor); WN, White noise; X, “blockade of”; ZB, zebra finches.

Plain midshipman fish have three adult morphotypes: females, type I (courting and vocalizing) and type II males (sneaking and satellite spawning at the nest).

these results represent the active doses obtained from studies where 2 or more doses were compared.

2.1. Aggression

In 1991, Hayden-Hixson and Ferris reported that a single injection of 17β-estradiol (E2) in the anterior-hypothalamus facilitated agonistic behaviors within 20 min in male hamsters [113]. In beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus) and California mice (Peromyscus californicus), males are more aggressive during short days mimicking winter conditions than in long days. In these two species, aggressive behavior E2 acutely (within 15 min) increases the number of bites while reducing the latency to attack in short but not in long days [270; 271]. Interestingly, a recent study conducted in song sparrows (Melospiza melodia morphna) found that E2 injections induce changes in intracellular signaling within 15 min, some of which are season-dependent [114] but unexpectedly these neurochemical changes were not associated with changes in behavior (aggression, singing, locomotion, maintenance behaviors).

2.2. Sexual behavior

Cross and Roselli initially found that an intraperitoneal injection of E2, but not testosterone, increases within 35 min the frequency of anogenital investigations and mounting behavior in castrated male rats (Rattus norvegicus; [63]). Subsequent studies conducted in castrated quail (Coturnix japonica) and mice (Mus musculus) treated with a sub-threshold concentration of testosterone demonstrated that peripheral administration of E2 acutely stimulates appetitive (a category of variable behaviors that serve to bring individuals into contact with their mates, often used as a measure of sexual motivation, e.g. courtship [13; 203]) and consummatory (highly stereotyped behaviors resulting in the termination of the behavioral sequence, e.g. actual copulation [13; 203]) aspects of male sexual behavior. These effects occur even faster than previously thought (within 10–15 min) and are transient; they disappear within 30–45 min of E2 administration [56; 264]. Conversely, blockade of estrogen synthesis with non-steroidal or steroidal aromatase inhibitors, Vorozole™ and androstatrienedione (ATD) respectively, rapidly and transiently reduces both behavioral components of male-typical sexual behavior [57; 264]. Several of these experiments were performed on castrates treated with exogenous testosterone. These observations thus suggested that the estrogens responsible for this rapid control of male sexual behavior are synthesized locally in the brain. In the absence of testes, the most likely site of aromatization was indeed the brain itself.

Direct evidence of the key role of local brain aromatization was recently provided by studies employing intracerebroventricular (ICV) injections of E2, ER antagonists or aromatase inhibitors in the third ventricle of Japanese quail [248]. A first experiment investigated the effect of acute E2 injections in castrated males chronically treated with testosterone and the aromatase inhibitor Vorozore™ in order to test the effect of a rapid increase in brain estrogen concentration. Chronic testosterone treatment allows the expression of all androgenic effects, while preventing estrogenic effects, and is known to reduce the display of appetitive sexual behaviors and profoundly inhibit copulation [263]. The ICV injection of E2 in these subjects chronically deprived from estrogens enhanced appetitive sexual behavior within 15 min [248]. No consummatory sexual behavior was exhibited by most subjects regardless of the dose and timing of the acute treatment with E2 suggesting that a prolonged exposure to E2 is required to prime this behavioral component by the transcriptional activity of estrogens, as indicated by earlier work in female rodents [133; 171; 172; 277].

A second set of experiments conducted in castrated male quail chronically treated with testosterone and displaying the full range of male sexual behaviors also showed that the aromatase inhibitors, Vorozole™ and ATD, profoundly reduce both the appetitive and consummatory components of male sexual behavior within 30 min. Furthermore, E2 injected 15 min after Vorozole™ counteracted the effect of aromatase inhibition thus demonstrating that this effect does not result from a non- specific effect of the blocker [248]. These data indicate that a local brain estrogen production is clearly implicated in the rapid activation of male sexual behavior in quail.

Finally, brain-derived estrogens also rapidly enhance visually guided sexual approaches in fish [153]. A single systemic testosterone injection to male goldfish (Carassius auratus) stimulates their approach toward the visual cues of a female within 30–45 min. This effect is mimicked by E2 within 10 min and blocked by an aromatase inhibitor administered along with testosterone thus indicating that the behavioral effect of testosterone requires its aromatization. In the same species, testosterone has recently been shown to rapidly increase through aromatization milt volume and sperm concentration [159].

2.3. Social communication (vocal production & perception)

Estrogens also rapidly influence social communication by altering vocal communication and/or the perception of species-typical auditory signals by conspecifics. To our knowledge, the only demonstration of rapid modulations of vocalizations by estrogens was reported in the plain midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus). In an anesthetized preparation of this species, systemic administration of E2 induces a rapid (5min) and transient (25–40 min) increase in the duration of fictive vocalizations reflecting the rhythmic activity of the vocal generator pattern in response trains of stimuli delivered to the midbrain [214; 215].

Evidence supporting an acute neuromodulatory role of brain-derived estrogens in auditory processing was recently provided by two independent groups working on songbirds (for reviews, see [158; 219]. Using simultaneous single unit extracellular recordings from neurons of the left and right caudomedial nidopallium (NCM, a telencephalic auditory region thought to be analogous to secondary auditory cortex in mammals) of awake zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata), Tremere and colleagues first demonstrated that E2 delivered in the vicinity of the recording site increases within 5 min the firing activity evoked by playback of conspecific songs as compared to recordings made in the contralateral site where the vehicle was injected. Estrogen receptors (ER) antagonists (Tamoxifen and ICI 182,780 [ICI]) prevented this response and even reduced song-evoked spiking activity below control levels suggesting that endogenous estrogens may be implicated in this process. Furthermore, similar effects were obtained following acute blockade of local estrogen synthesis (Table 1), confirming that these effects rely on local estrogen provision. These effects are sustained for at least 2 hours but are no longer present 4 hours after the injection [272; 273]. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings in slices revealed that E2 action in NCM is mediated through changes in GABA transmission probably involving a modulation of GABA release [272].

Using multi-unit recording coupled with E2 retrodialysis, Remage-Healey and colleagues subsequently showed that a 30 min provision of E2 in the NCM of anesthetized male zebra finches selectively increases the firing rate and bursting activity in response to playback of stimuli containing elements of conspecific songs (bird own song, novel conspecific song or reversed conspecific song). This effect is no longer detected after a wash out period of 30 min. By contrast, aromatase blockade produces either no change or a decrease in this selectively depending on the neurophysiological parameter studied [218].

Similarly, Tremere and Pinaud showed that locally produced E2 enhances neuronal discrimination through the modulation of the information content of auditory signals. These processes occur within 5 min, are prolonged for at least 2 hours past the initial injection but vanish within 4 hours [273]. Thus, although there are a few discrepancies in the characteristics of these effects (see Table 1) most likely due to protocol and technical differences between studies, together these data provide evidence supporting a role for locally produced estrogens in the control of auditory processing and more specifically in the ability of NCM neurons to discriminate between species-specific auditory cues. Interestingly, similar processes have recently been described in females [221]; see also below).

Importantly, both the Remage-Healey and the Pinaud and Tremere groups demonstrated that brain-derived estrogens acutely strengthen the bird’s preference for conspecific auditory cues. When given a choice between their tutor's or their own song (bird's own song or BOS) and the song of another conspecific, male zebra finches prefer their tutor's song or BOS. In 2010, Remage-Healey and collaborators first showed that fadrozole retrodialysis in the left, but not the right, NCM acutely disrupts this preference in awake and freely moving male zebra finches [218]. Tremere and Pinaud further demonstrated that the bilateral injection of ER antagonists or aromatase inhibitors in NCM impairs the preference for the tutor's sone relative to a novel conspecific song. This behavioral preference seems specific for learned songs since E2 did not affect the birds’ ability to discriminate between female and male calls [273]. Therefore, these data support the notion that locally synthesized estrogens acutely control the auditory-evoked spiking neuronal activity, which translates equally rapidly into changes in behavioral song discrimination. Interestingly, the inner ear of zebra finches also expresses aromatase and ERα [186] suggesting that the control by estrogens of auditory performance could take place both centrally and peripherally.

2.4. Locomotion and nociception

In the striatum, estrogens are known to affect in both sexes motor responses controlled by striatal dopamine [25]. Some of these responses have been shown to occur relatively quickly. For example, 17β- and 17β-estradiol administered in the striatum potentiate within 4 hours dorsal immobility in both males and females, although males respond better than females [275]. In males, this response is not mimicked by testosterone [276]. Faster effects of striatal administration of E2 have been detected in other motor responses (e.g. E2 enhanced sensorimotor performance [24], increased amphetamine-induced rotational behavior [246]), but these have been investigated in females only (for a review see, [25; 59]). These effects of estrogens appear to rely on the acute and non-genomic potentiation of dopaminergic activity that in turn enhances sensorimotor processing.

In both sexes of a variety of species including humans, estrogens are involved in the control of nociception and analgesia namely through their genomic action on the opioid and adrenergic systems both at the central and peripheral level [9; 71; 84; 86; 92; 149]. Locally produced estrogens also rapidly impair the perception of noxious stimuli. Indeed, in quail, acute aromatase blockade obtained by intrathecal injection of an aromatase inhibitor increases within 1–5 min the latency for foot withdrawal from a noxious stimulus. This effect is by-passed by a concomitant injection of E2. This change in pain threshold is transient as it is no longer detected 30 min post-injection. It is also anatomically restricted given that intrathecal spinal but not intracerebroventricular injections mimicked the effects obtained after systemic injections [85].

2.5. Learning and cognition

Estrogens can also influence by non-genomic mechanisms the firing rate, synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and cortex in mammals ([96; 104; 134; 156; 180; 253; 258; 288, 289; 291]; For review see, [259; 290]). These observations suggested that acute actions of estrogens might play an important role in learning and memory processes that are known to be mediated by these structures. This hypothesis was confirmed by studies from several laboratories that employed a variety of cognitive tests. In females, systemic or intra-hippocampal administration of estrogens (17β- but, sometimes also, 17α-estradiol) immediately prior to or after (but not several hours after), the training session were shown to enhance memory acquisition or consolidation ([22; 88; 102; 110; 121; 147; 148; 155; 195; 196; 204]; for review see: [46; 47; 97; 154; 197]). Although the hippocampus of males also synthesizes estrogens [116; 240], far less is known about their acute impact on cognitive processes. In 1996, Packard and colleagues showed that rats that received intra-hippocampal injections of E2 immediately post-training, but not 2 hours later, displayed a lower latency to escape in the Morris water maze, a result indicative of enhanced spatial memory [194]. Other reports support a role for estrogens in learning processes in males but (1) these studies involve long-term exposures to the steroid precluding any statement about the temporal resolution of the observed effects and (2) they sometimes provide contradicting results such that there does not seem to be a consensus supporting a role of locally synthesized estrogens in males at the moment [99; 143; 161; 178; 187].

3. Identification of membrane estrogen receptors

Because estrogen receptors do not possess any intrinsic trans-membrane domain and are most often found in the nucleus, it had been originally thought that non-genomic actions of estrogens were mediated through a novel receptor. Over the years, several such novel receptors have been discovered that exhibit specific pharmacological properties and are associated with the neuronal membrane. Functional studies have also indicated that these new membrane receptors could mediate rapid effects of estrogens. In addition, it has turned out that, following post-translational modification and protein-protein interactions, a fraction of the classical nuclear receptors, ERα and ERβ, are translocated to the membrane where upon binding to estrogens they can activate multiple intracellular signaling cascades. All these membrane receptors seem to play an important role in the control of rapid behavioral responses to estrogens and therefore need also to be considered in detail.

The presence of classical nuclear estrogen receptors at the membrane in brain cells had been first described in the early 1990s [29]. It has been confirmed by more recent studies [112; 173], but, the first indication of ER trafficking to the membrane originated from studies that employed cancer cell lines and endothelial cells. These experiments showed that ERs interact with complexes of membrane-associated proteins including caveolin-1 or the adapter protein shc [199; 210; 211; 212; 255]. It was also demonstrated that membrane-associated ERs must undergo palmitoylation, a post-translational modification resulting in the addition of a lipid-moiety that permits intracellular trafficking and association with specific subcellular domains such as the caveolar rafts of the plasma membrane [5; 199]. In these cellular models, the membrane-associated ERs act as G-protein coupled-receptors, interact with growth factor receptors such as the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor and insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor and trigger the phosphorylation of intracellular messengers ([213; 256]; For review see, [145; 146]). Similarly, recent work demonstrated that a brief exposure to E2 induces in both sexes the trafficking of ERα and ERβ to the membrane of neurons and astrocytes involving an interaction with caveolins ([32; 79; 101; 250]; for review, see [171]). At the membrane, ERs can interact with metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) whose trafficking to the membrane is influenced by estrogens in parallel with ERs [32; 67; 79]. E2 action on these membrane-associated ERs results in the transactivation of mGluRs, that in turn attenuates L-type calcium channel currents and calcium-dependent phosphorylation of CREB or increases the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent CREB phosphorylation [33; 38; 67; 103]. The type of mGluR and response activated depends on the brain region and the cell type considered (For review, see [165]). It has to be noted that the function of this interaction has only been studied in females. Finally, it has also been shown that ERα and ERβ interact with IGF-I signaling (For review, [82; 167]). Both estrogens and IGF-I share similar signaling pathways, among which the phosphatidylinositol phosphate-3-kinase (PI3K) and MAPK signaling pathways are the best characterized. Co-localization between IGF-I receptors (IGF- IR) and ERα has been demonstrated in the rat brain [36] and a one-hour exposure to E2 induces a transient association between ERα and IGF-IR in the hypothalamus of ovariectomized females [166]. This interaction has been proposed to regulate estrogen-dependent neuroplasticity [89], the LH surge [209] and lordosis behavior [81; 209]. To our knowledge, the existence of this interaction has never been investigated in males. Note that, although rapid behavioral effects of estrogens have also been identified in birds and fishes (table 1), there is to this date no evidence demonstrating the presence of nucleus ER at the level of the cell membrane in these species. Moreover, two isoforms of ERβ have been identified in fishes [200].

Three novel membrane estrogen receptors (mER) have been described to date. ER-X is the least characterized of them. It has been described in the developing neocortex and uterus of ERα-knock out (KO) mice. This putative receptor is enriched in caveolar-like microdomains and activates MAP kinases. Its pharmacological profile differs from ERα and ERβ in that it is activated by both 17β–and 17α–estradiol whose action is not affected by the ER receptor antagonist ICI 182,780. It is recognized by antibodies raised against ERα, but its apparent molecular weight is different from the molecular weight of the main isoforms of the classical nuclear ERs. The expression of ER-X in the neocortex and uterus is maximal at post-natal day 7 to 10 (P7–10), then gradually decrease until P21 and is dramatically decreased in adulthood. ER-X is also up-regulated following brain injury. However, its molecular identity is still unknown [267].

GPR30 (or GPER) is a G-protein coupled-receptor that works in concert with the EGF receptor ([90; 222; 265]; for review see [91; 266]). It is found in numerous tissues including the brain of birds and mammals [6; 34; 108; 122; 238]. In fishes, this receptor has so far only been reported in the gonads [266]. Questions have been raised about its cellular location, some have described it at the cell membrane [265] while others have observed it in the endoplasmic reticulum [192; 222]. Furthermore whether GPR30 actually binds and is activated by E2 is still subject of debate ([192; 193]; for review, see [140; 190]). Interestingly, the general ER antagonists ICI 182,780 and tamoxifen act as full agonists on GPR30 [222; 265]. Unlike ER-X, GPR30 appears stereospecific as it only binds 17β-estradiol. Recently, an agonist (G1) and an antagonist (G15) that do not cross-react with classical ERs have become available [31; 66; 185] and have facilitated the demonstration that this receptor is implicated in several neurophysiological processes [141; 151; 185; 261]. As these studies were conducted in females, less is still known on the function(s) of this receptor in males.

Gq-mER is another G-protein coupled-receptor originally identified in the hypothalamus. Its pharmacological profile is closer to ERα and ERβ than the other two mERs. Indeed, it is activated by 17β-, but not 17α-estradiol, and is antagonized by ICI 182,780. E2 effects mediated by Gq-mER are mimicked by the specific synthetic agonist STX, which activates a PLC-PKC-PKA pathway resulting in the uncoupling of mu-opioid and GABAB receptors from their effector (G-protein coupled inward rectifying potassium channel, GIRK) in POMC neurons of the arcuate nucleus [207]. This receptor also reduces the excitability of GnRH neurons [293] and increases the frequency of their calcium oscillations [127]. Finally, it was recently implicated in the control of energy homeostasis and thermoregulation [208; 223] as well as hippocampal neuroprotection [142]. Some of the physiological responses that are characteristic of Gq-mER and mimicked by STX have been reported in double ERαβ-KO mice [208] suggesting that it is not a product of the genes coding for ERα or ERβ. Unfortunately, as for ER-X, its molecular structure still remains to be uncovered.

4. Membrane estrogen receptors and male physiology and behavior

With this information in mind, we can now start discussing the nature of the receptors that might be involved in the regulation of the physiological and behavioral processes described above. Male sexual behavior is severely impaired in ERαKO [188; 284]; but much less so in ERβKO mice [30; 189]. Male sexual behavior is also profoundly inhibited in non-classical ER knock-in (or NERKI) mice with a mutated ERα knock-in that cannot bind to ERE and consequently signals only through membrane-initiated or ERE-independent genomic pathways [162]. Combined with the idea that some genomic priming is required to observe rapid effects of estrogens on male sexual behavior [56; 264], these results suggest that the acute control of male sexual behavior by estrogens likely involves an integration of non-genomic and genomic processes depending on ERα, at least in part. Interestingly, copulatory behavior was facilitated within 48h after the bilateral implantation of E2-BSA in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) of castrated male rats chronically treated with the androgenic metabolite of testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT; [119]). This observation first suggested that estrogen membrane signaling was involved in the control of male sexual behavior. This has recently been confirmed by studies conducted in quail. Indeed, in castrated males chronically treated with testosterone and the aromatase inhibitor Vorozole™, the membrane impermeant analog E2-BSA rapidly restores appetitive sexual behavior. Moreover, DPN, a specific ERβ agonist and, to a lower extent, PPT, a specific ERα agonist, produce a similar behavioral activation as estradiol. Conversely, acute treatment with MPP, a specific ERα antagonist without behavioral activity when administered alone, completely abrogates the facilitating effect of estradiol on behavior [249]. Likewise, in castrated males chronically treated with testosterone, the acute inhibition of appetitive and consummatory sexual behavior resulting from aromatase blockade is prevented by the administration of E2, its membrane- impermeant analog E2-biotin and DPN but not PPT [249]. Together, these results suggest that the rapid action of brain-derived estrogens on male sexual behavior is initiated at the cell membrane and likely involves both classical ERs. The determination of the relative contribution of each receptor to this response will require further study. The role of GPR30 and STX in this experimental model is under investigation.

Much less is known about the receptor types involved in the acute estrogen effects on the other social behaviors. No information is available regarding the receptor underlying the rapid action of estrogens on aggression. However, long-term exposure to both PPT and DPN significantly alters different aspects of aggressive behavior suggesting that both classical receptors might be involved [270]. As for communication, it was recently demonstrated that the membrane-impermeant E2- biotin produces the same effect as E2 on auditory processing in songbirds [221] thus indicating that these acute effects are initiated at the membrane. The auditory cortex expresses both types of nuclear estrogen receptors [27; 123; 169] as well as GPR30 [6] suggesting that the three receptors might contribute to this effect. There is however no evidence so far that ERα and/or ERβ associate with the cell membrane in this brain area of songbirds.

Recent evidence also supports an involvement of these three receptors in the control of nociception and analgesia. First, in females, E2-BSA mimics the inhibition of the ATP-induced increase in intracellular calcium concentrations induced by E2 within 5 min in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) that contains a subset of nociceptive neurons [39]. This inhibition is detected in mice lacking ERβ but not in those lacking ERα indicating that this non-genomic modulation of DRG signaling is mediated through ERα [40]. Moreover, it is attenuated by blockade of group II mGluRs [37] suggesting that this response might be mediated through the transactivation of mGluRs. Secondly, morphine-induced anti-nociception in females is acutely blocked by the general ER antagonist ICI 182,780, the selective ERα and ERβ antagonist, MPP and PHTPP respectively, and the specific GPR30 antagonist G15 [150] suggesting that several receptor types are involved in the control of this response. Finally, the acute mechanical hyperalgesia induced by E2 injection into the hind paw of male rats is mimicked by the GPR30 antagonist and by the general ER antagonist ICI 182,780 indicating a role for GPR30 [138].

Finally, analyses of the intracellular events involved in the effects of E2 on hippocampus-dependent tasks in females suggest that they might be mediated by ERβ activation, initiated at the cell membrane and depend on the activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK/MAPK) pathway [88; 148]. In addition, it might be inferred from the absence of stereoselectivity observed in some studies [155; 156] that ER-X might be at play, yet more work is needed before a firm conclusion can be drawn. A similar conclusion can be drawn from the potentiation of tonic immobility induced by both 17α- and 17β-estradiol [275; 276].

5. Interaction with genomic effects

The mechanisms controlling behavior involve chains of molecular and neurophysiological events precisely organized in time and space (from the intracellular space to neuronal networks controlling motivation or motor patterns). One can thus assume that, in vivo, the non-genomic effects of estrogens should produce observable effects on behavior after slightly longer latencies than the intracellular events (triggered within a few seconds to minutes [55]) that underlie them. As illustrated in preceding sections, multiple experiments have identified physiological or behavioral responses triggered by estrogens that occur after a few minutes to an hour. These effects should be regarded as extremely rapid when compared to genomic effects of estrogens on behavior that are typically detected following several days of treatment. Given this very short time course and their activation by membrane impermeant estrogen analogs, it is thus very likely that they rely on a non-genomic action rather than on a regulation of gene transcription.

Although the cellular events initially triggered by E2 acting at the cell membrane do not involve protein synthesis, the intracellular cascades activated by these events very often lead to indirect transcriptional activation [3; 114; 272] and both types of events might be required for the expression of a given behavior. One of the best-studied examples of such cooperation between non-genomic and genomic effects of estrogens concerns the control of female sexual receptivity (reviewed in [59; 172; 278]. In brief, numerous studies conducted by independent research groups indicate that, early events activated by E2 at the cell membrane affect an intracellular chain of events that ultimately facilitate lordosis but also trigger long lasting effects that likely result in the indirect modulation of protein synthesis (indirect genomic mechanisms involving pCREB binding to cAMP response elements (CRE) sites on the DNA; [3; 33]). These membrane-initiated effects of E2 also interact with classical genomic actions involving the interaction with estrogen-response elements (ERE; e.g. activation of progesterone receptor transcription required for progesterone action) or ERE-independent sequences (Reviewed in [163]).

As far as we know, the existence of membrane-initiated indirect genomic activation by E2 and its role in the control of physiological and behavioral processes has never been investigated in males. The existence of a major sex difference in the rapid intracellular signaling activated by estrogens has been suggested in gonadectomized mice: E2 action was in this study enhancing CREB phosphorylation within an hour in females but not in males [4]. Yet, recent studies showed that acute administration of estrogens also results in CREB phosphorylation in males of avian or rodent species [114; 148]. One explanation for the apparent lack of effect of estrogens previously reported in male rodents [4; 33] is that these effects might require long- term exposure (priming) by androgens. Indeed, the studies that failed to identify an E2-induced CREB phosphorylation in males were carried out on gonadectomized males while others used gonadally intact subjects with or without chronic treatment with an aromatase inhibitor to deprive them of estrogens while maintaining normal concentrations of circulating androgens.

Finally, it should be noted that the changes in cognitive behavior described previously develop over the course of several days following repeated injections with estrogens [155; 156; 194]. It could thus be hypothesized that these effects reflect transcriptional activation rather than non-genomic actions. However, the timing of E2 injections relative to cue exposure and testing was shown to be critical: estrogens facilitate learning and memory when administered before or immediately after but not two hours after training. It can thus be concluded that the resulting cognitive changes depend, at least in part, on non-genomic mechanisms for which a short-term exposure to the active hormone is sufficient. Of course, any exposure (short, prolonged or repeated) to estrogens also activates genomic effects that likely participate in the long- term modifications of synaptic plasticity and cognitive abilities arising in these learning paradigms [148].

6. General features of non-genomic behavioral effects of E2 with a special emphasis on active doses

In summary, as illustrated in table 1, collectively, these studies demonstrate the implication of membrane-initiated effects of estrogens in multiple physiological and behavioral endpoints in a variety of vertebrate species. Most of these effects are detected within 5 min to an hour of the injection and last for a limited period of time. Such latencies can be considered to be extremely short when compared to the typical latencies required to detect behavioral effects resulting from genomic activation. There seems to be no rule relating the latency of the effects to the species analyzed nor to the type of behavioral response under investigation. It is likely that variations in the latency of estrogen action relates to the diversity of the underlying signaling pathways. More studies would obviously be needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The transient nature of these non-genomic behavioral actions of estrogens also contrasts with the enduring effects typical of genomic actions. Importantly, some of these effects are clearly region specific. Finally, these effects do not occur independently from genomic actions. In some cases, membrane-initiated actions potentiate genomic actions [277], while in others some genomic priming seems required to allow expression of non-genomic effects [248; 249]. These effects thus seem to share important properties: they occur across a wide range of species from fishes to mammals, they are rapid, often transient, anatomically confined and integrated with genomic action.

The active dose of estrogens mediating acute regulation of behavior requires a more elaborate discussion. It was originally assumed that non-genomic effects of estrogens would only be observed after injections of very large doses of the steroids. The reasoning was that non-genomic effects of estrogens are largely, if not exclusively, mediated by actions at the synapse of steroids produced at the pre- synaptic level and thus present in extremely high concentrations locally at the synapse but that were impossible to measure by available technologies. It was therefore necessary to inject very large doses that were obviously non-physiological in the periphery to mimic at the synaptic level a concentration that was actually physiological. The first studies investigating effects of exogenous estrogens on male sexual behavior accordingly employed fairly high doses of steroids (e.g., [54; 63; 214]) and thus seemed to support this interpretation. Some of these papers (e.g., [54]) additionally included dose-response studies indicating that the high doses (e.g. 500 µg/kg in quail) were actually required to obtain a fast behavioral response.

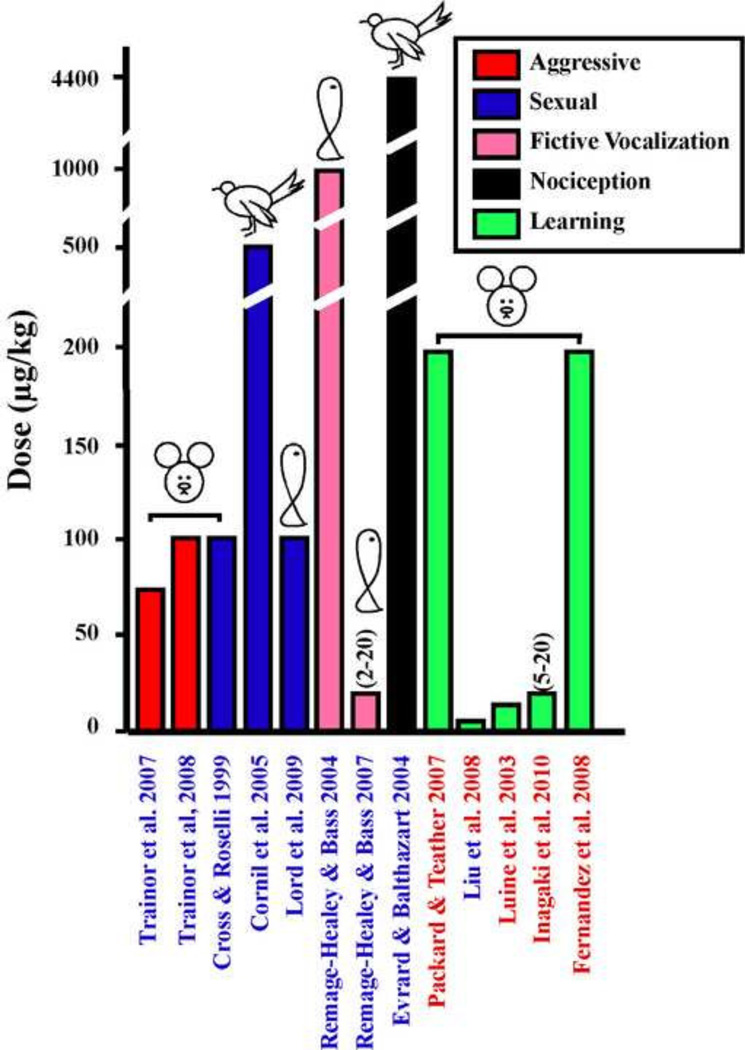

Since that time, fast behavioral effects of estrogens obtained with much lower doses (2–20 µg/kg) have been reported in both sexes in at least two different classes of vertebrates. As can be seen in figure 1, the range of behaviorally active doses is extremely wide and no general rule seems to emerge from the comparison of these high and low doses. They are not obviously associated with the sex of the subjects, nor with the type of behavior under consideration. Higher doses have usually been used in birds, which might be related to their higher body temperature and thus metabolism, but there are also studies in mammals (homeotherms with a lower body temperature) or fish (poikilotherms) that use doses in the same range.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the doses of estradiol expressed in µg/Kg that were shown to modulate after short latencies (15 to 60 min) the expression of behavior. The different bars are color coded to reflect the type of behavior under study as explained in the insert. References to the relevant work (X axis) are in blue for studies performed in males and in red for studies performed in females. One study carried out on both sexes is indicated by both colors. The class of vertebrates in which the study was performed (mammals, birds or fishes) is indicated at the top of the bars by a schematic drawing as well as the range of doses when multiple doses were used in a given study.

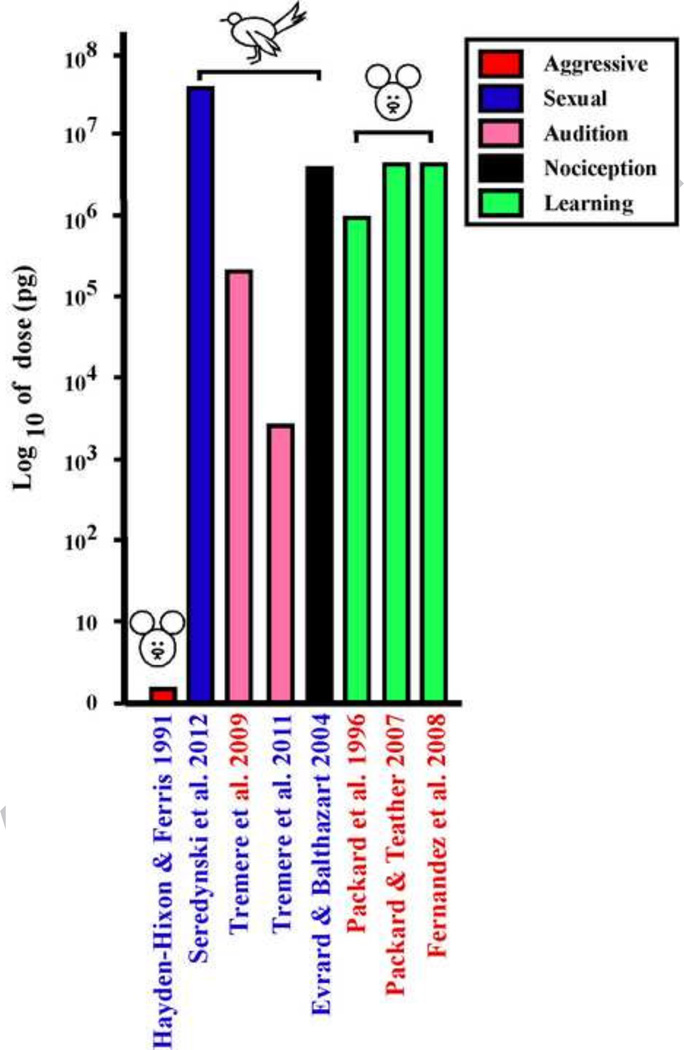

The comparison of doses used in experiments based on central injections show a similar or even a broader degree of diversity (see Figure 2). It makes no sense in this case to relate these doses to the body mass of the animals that are treated and absolute values of amounts injected are directly presented. As can bee seen, these doses range from 27 pg to 50 µg that is more than a million (106) fold difference. Here again, no rule seems to govern these differences: high and low doses have been used successfully in birds and in mammals irrespective of the behavioral response that was investigated.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the doses of estradiol injected centrally (ICV) in pg/subject that were shown to affect after short latencies (15 to 60 min) the expression of behavior. Note the logarithmic scale on the Y axis. The different bars are color coded to reflect the type of behavior under study as explained in the insert. References to the relevant work (X axis) are in blue for studies performed in males and in red for studies performed in females. One study carried out on both sexes is indicated by both colors. The class of vertebrates in which the study was performed (mammals, birds or fishes) is indicated by a schematic drawing at the top of the bars as well as the range of doses when multiple doses were used in a given study.

In conclusion, while the existence of rapid behavioral effects of estrogens can no longer be denied today given the large number of experiments that have successfully identified them, a major question remaining is to determine what are the active doses and why they differ so much from one experiment to another. It seems likely that these differences will relate to the type of membrane receptor and/or to the intracellular signaling cascade mediating the response. However, to this date, the available data do not permit a test of these hypotheses.

7. What is the source of estrogens?

Males are not exposed to the dramatic changes in circulating concentrations of estrogens experienced by females across the estrus cycle. Although prolonged exposure to estrogens can induce non-genomic signaling, membrane-initiated effects in neurons desensitize relatively rapidly ([32; 78; 79; 101]; reviewed in [170; 172]). Moreover, estrogen receptors are likely to be present in a fairly stable manner in the brain. Together, these observations suggests that if estrogens induce rapid and transient behavioral effects in males, mechanisms must exist to regulate local estrogen concentrations on much shorter time scales. Brain aromatase, which is expressed and active especially in brain regions controlling aggressive and sexual behaviors [14; 49; 93; 137; 226; 227; 229; 233; 234; 280; 282] but also in the hippocampus [14; 226; 229; 233; 239; 240; 260; 282], was thus considered as a potential local source of estrogens. However, due to their lipophilic nature, estrogens cannot be stored in synaptic vesicles before rapid release like classical neurotransmitters or neuropeptides. Therefore, in order to achieve rapid changes in local concentrations, it becomes necessary to invoke the existence of regulatory mechanisms that are able to change the local synthesis and bioavailability of estrogens in a dynamic manner, very much as is the case for gaseous neurotransmitters [19].

Estrogens are synthesized from androgens by aromatase, a P450 enzyme traditionally associated with microsomes. The enzyme is mainly expressed in the ovaries but is also found in many other tissues including the brain. In reptiles, birds and mammals, brain aromatase expression is restricted to specific neuronal populations mainly located in the hypothalamic/preoptic area (HPOA) including the medial preoptic nucleus and in the limbic system [11; 49; 60; 93; 136; 137; 169; 226; 227; 228; 229; 233; 234; 240; 260; 280; 282]. In songbird species, aromatase is found in another neuronal population located in the caudomedial nidopallium NCM, a pallial area (homologous to secondary auditory cortex in mammals) adjacent to the song control nucleus HVC (acronym used as proper name [14; 240; 251]). In teleost fishes, aromatase is abundantly expressed but specifically in glia ([73; 94]; For review, see [72; 95]). Finally, both the aromatase protein and activity are also detected in pre- synaptic terminals of various species [61; 183; 202; 225; 230; 244], suggesting that E2 synthesis may be achieved with a spatial subcellular specificity similar to neurotransmitters and neuromodulators [19; 242]. The presence of active aromatase in synapses of discrete brain regions indicates that estrogen provision can be modulated with a high spatial resolution independently from changes occurring in the periphery and/or surrounding brain regions.

As alluded to in the introduction, brain aromatase is known to play a key role in the control of a variety of physiological and behavioral endpoints including sexual behavior, neuroprotection and synaptic plasticity. However, until recently most studies investigated relatively slow, presumably genomic, effects of estrogens and, correlatively, most research on the regulation of aromatase activity focused on the genomic regulation of the enzyme concentration in parallel with relatively slow and enduring changes in reproductive states (seasonal changes). In the following sections, we will provide evidence gathered both in vitro and in vivo that aromatase activity can vary in a much shorter time scale that could produce variations in estrogen availability compatible with their rapid non-genomic actions. Rapid fluctuations in local estrogen concentrations can theoretically arise from variations in the enzymatic substrate concentration (testosterone) or in the catalytic ability of the enzyme (its efficiency), two mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive. The resulting changes in local estrogen provision could simultaneously provide answers to the issue of the source of rapid changes in their bioavailability and offer the spatial resolution that fits with the behavioral results described above.

8. Rapid changes in gonadal secretions

One way through which brain estrogens concentrations could be rapidly modulated involves rapid changes in peripheral androgen concentrations that would be available for local aromatization. Thus, short-term (min to hours) fluctuations in testosterone secretion from the testes in response to the pulsatile release of the luteinizing hormone from the pituitary may theoretically result in changes in local estrogen concentration in brain region expressing aromatase. Moreover, a sharp increase in plasma testosterone has been reported in response to social encounters such as territorial intrusion or sexual interactions (for review see [111; 191; 287]. Although most of these changes in gonadal secretions occur relatively slowly (for extensive review, see [55; 100; 286]), the fastest effects occur within 5–15 min [7; 23; 206; 237]. Interestingly, social stimulations, such as aggressive encounters, can also rapidly up- regulate the local synthesis of androgens in the brain [205]. Such rapid increases in the concentration of aromatizable androgens could translate into rapid and transient changes in local estrogen production by neural aromatization (reviewed in [55; 59]). This is for example the case in goldfish in which we have seen that an acute injection of testosterone, mimicking the rapid increase in androgen secretion occuring in the context of reproduction, facilitates visually guided sexual behavior and induces a rapid increase in milt volume and sperm concentration through aromatization [153; 159]. By contrast, in quail, two independent studies recently showed that the plasma testosterone concentration drops after sexual encounters but these changes do not seem dynamic enough to drive the rapid behavioral effects of estrogens [58; 65].

9. Rapid regulation of aromatase activity

In vitro studies taking advantage of the high concentrations of the aromatase protein present in the avian brain have recently demonstrated that aromatase activity (AA) can be rapidly modulated. In preoptic area/hypothalamus (HPOA) explants from Japanese quail, an acute increase in extracellular K+ concentration results in a rapid (5 min) and reversible reduction of AA (Figure 3A) [16]. A similar effect is obtained after incubation with thapsigargin, a sesquiterpene lactone that increases the intracellular pool of Ca2+. Several experiments subsequently tried to determine whether the K+-induced enzymatic inhibition is mediated by Ca2+ from extracellular origin or derived from intracellular stores (e.g. by incubating the hypothalamic blocks in a Ca2+-free medium or by producing a K+ depolarization in the presence of Ca2+ channel blockers) but additional work would be needed to draw final conclusions on this question [16]. It remains that collectively, these results show that a transient depolarization induced by elevated K+ extracellular concentration markedly and reversibly inhibits aromatase activity presumably by modulating intracellular Ca2+ concentrations.

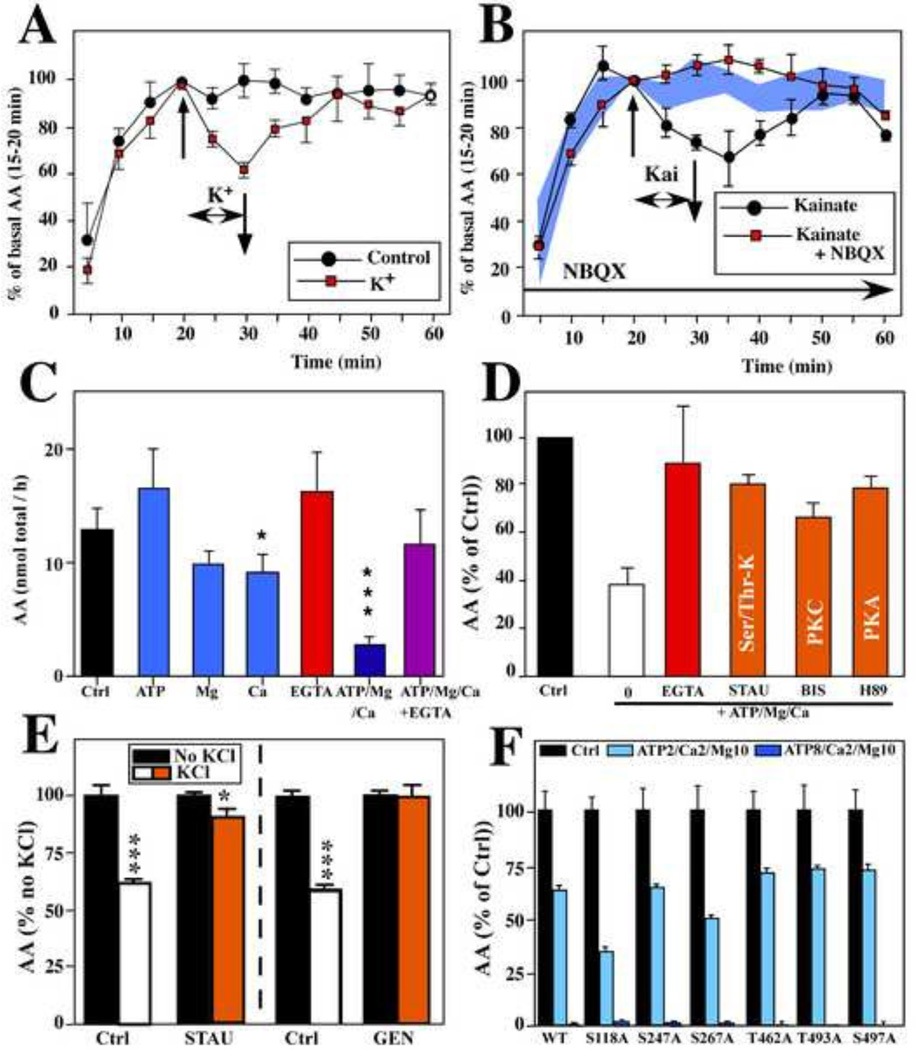

Figure 3.

Rapid changes in aromatase activity (AA) observed in hypothalamic- preoptic (HPOA) explants cultured in vitro (A-B), in HPOA homogenates (C-D) and in HEK293 cells transfected with human aromatase (E-F). All values are presented as mean ± SEM.

In explants, AA is inhibited within 5–10 min by a K+-induced depolarization (A) or by exposure to the glutamate receptor agonist kainate (B). This latter effect is blocked by co-exposure to the glutamate antagonist NBQX. The values observed in control conditions in the absence of any pharmacological treatment are indicated by the blue area. C. A 15 min pre-incubation of HPOA homogenates in the presence of ATP, Mg2+ and Ca2+ markedly inhibits AA, but these compounds alone have little or no effect. This inhibition is blocked by EGTA, a compound that chelates divalent ions such as Ca2+. D. The inhibition of AA produced in HPOA homogenates by the addition of ATP/Mg/Ca is largely blocked in the presence of EGTA or of the kinase inhibitors staurosporine (STAU, a Serine Threonine kinase inhibitor), Bisindolylmaleimide (BIS, a protein kinase C [PKC] inhibitor) or H89 (a protein kinase A [PKA] inhibitor. E. AA expressed by HEK293 cells is inhibited by a K+- induced depolarization and this effect is largely blocked by exposure to the protein kinase inhibitors staurosporine (STAU) or genistein (GEN). F. Effects of single amino acid mutations in the human aromatase expressed by HEK293 cells on the AA expressed in control conditions (black bars) and after pre-incubation with 2 mM Ca2+10 mM Mg2+, and 2 mM (pink bars) or 8 mM (red bars) ATP. AA in phosphorylating conditions is expressed as percentage of the mean activity compared in control conditions. No significant effect of the mutations is observed on the response to phosphorylating conditions (S=serine; A= alanine). * p < 0.05 vs CTL in (C), * and *** p <0.05 and 0.001 respectively vs No KCl conditions, same treatment in (E). Redrawn from data in [16] (A, C), [18](B), [17] (D) and [43](E,F)

Similar enzymatic down-regulations are also triggered by glutamate [16]. More specifically, the ionotropic glutamate receptor agonists AMPA, kainate and, to a lesser extent, NMDA rapidly (within 5 min) and reversibly decreased AA [18]. The effect of kainate was antagonized by the glutamate receptor antagonists CNQX and NBQX (Figure 3B) [18]. Calcium removal from the medium had no effect on the decrease in AA induced by glutamate suggesting that the effect of the activation of glutamate receptors on AA is not mediated by extracellular calcium influx into the neurons but by another signaling mechanism possibly including the release of calcium from intracellular stores [16]. Electrophysiological recordings demonstrated that aromatase-expressing neurons are sensitive to glutamate, a finding consistent with the view that glutamatergic inputs on aromatase cells acutely regulate AA [52; 53].

These rapid changes of aromatase activity are most likely mediated by post- translational modifications of the enzymatic protein rather than transcription- dependent modulations of its concentration. Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylations are a common mechanism of control of protein activity in the brain [184]. The transfer of the terminal phosphate group from ATP to specific amino acid residues (tyrosine, threonine, serine) of the protein (i.e. phosphorylations) is catalyzed by specific kinases and often critically depends on divalent cations such as Mg2+ and Ca2+. Pre-incubation of male quail HPOA homogenates with high but physiological concentrations of ATP, Ca2+ and Mg2+ significantly inhibited AA. This effect was prevented by EGTA, a Ca2+ chelator, (Figure 3C; [16]) and by different kinase inhibitors (Figure 3D) thus strongly suggesting that this rapid regulation of aromatase catalytic ability is regulated by calcium-dependent phosphorylation processes [16; 17]. Direct evidence that aromatase itself is targeted by phosphorylation(s) rather than another co-existing protein that could secondarily regulate aromatase was provided in cultured cells transfected with human aromatase in which phosphorylated residues were detected on the immunoprecipitated protein after incubation with ATP/Mg/Ca [17; 43]. Importantly, AA is also rapidly and reversibly inhibited by KCl-induced depolarization. This response is blocked by kinase inhibitors thus demonstrating that the depolarization-induced changes in AA, described in HPOA explants, are likely mediated by phosphorylation processes (Figure 3E). The quantification of the enzymatic protein confirmed that this rapid enzymatic down-regulation does not result from protein degradation thus confirming the hypothesis that aromatase is regulated by conformational changes that do not involve new transcription [43]. Together these data strongly suggest that these phosphorylations directly cause the rapid decrease of enzymatic activity.

A bioinformatic analysis of the quail and human aromatase coding sequences identified several potential phosphorylation sites [17; 43]. Targeted mutagenesis of selected residues failed to identify one residue specifically involved in the acute regulation of aromatase activity (Figure 3F) [43] suggesting that another residue or a combination of several phosphorylated residues is likely required to control AA (for further discussion of these data see [43; 45]).

Interestingly, the phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of AA is observed in both male and female quail HPOA and in the songbird telencephalon [61; 130]. In addition, the rapid inhibition of AA by calcium-dependent phosphorylations is not specific to neuronal aromatase as similar effects were recently described in the ovary [43] and in neuronal or non-neuronal cell lines stably expressing human aromatase [43]. These data show that the regulation of aromatase by phosphorylations is a general process, found not only in birds, but also presumably in humans and other mammals. Finally, recent evidence suggests that these phosphorylating conditions preferentially affect synaptic aromatase compared to the enzyme isolated from microsomes, leading to the provocative idea that rapid changes in estrogen synthesis would mainly occur at the synapse allowing a precise spatial resolution for estrogen provision ([61], see also below).

In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that AA is rapidly controlled via post- translational modifications. This basic effect is observed in several tissues that express aromatase as well as in a variety of species, including humans and thus seems to be robust. Although much remains to be discovered with respect to the molecular mechanisms that mediate these effects, these rapid enzymatic changes must result in fluctuations of estrogen availability with a time and spatial resolution consistent with the non-genomic behavioral effects described earlier.

10. Aromatase activity is rapidly modulated in vivo

As demonstrated in the first part of this review, acute blockade of aromatase activity rapidly alters numerous physiological and behavioral processes (Table 1). This observation suggests that rapid modulations of estrogen synthesis similar to these described in vitro must also occur in vivo in functionally relevant contexts. The first evidence supporting this hypothesis came from work carried out in Japanese quail [54], that has recently been confirmed and expanded ([65; 68; 69; 70]; for review see also [62]). An important body of work supporting this idea is also provided by work on songbirds primarily in the context of social communication [43; 216; 217; 220; 221] for review see [219; 242]).

10.1. Effect of sexual interactions

A first study demonstrated that the enzymatic activity measured in HPOA homogenates is modulated in a time-dependent fashion following both visual access to or copulation with a female. However, against all expectations, these sexual interactions resulted in a decrease in AA that was detectable after 1 min and reached its maximum after 5 min. The amplitude of this effect (20% change) is much less dramatic than the enzymatic changes observed in vitro (nearly complete inhibition). This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that the HPOA contains several populations of aromatase-containing cells that may be differentially controlled by behavioral interactions. This might result in a dilution of large effects located in discrete regions or in changes occurring in opposite directions that might partially cancel each other out. This former hypothesis was confirmed by a follow-up experiment investigating the time course of the effect of copulation on AA measured specifically in the different populations expressing high levels of aromatase activity that were in this case dissected by the Palkovits punch method adapted for quail [60; 247]. This second experiment identified rapid enzymatic inhibitions in the medial preoptic nucleus (POM) and the tuberal hypothalamus [65]. The fastest change was detected in the tuberal hypothalamus after only 2 min of interaction (-25%) and was followed at 5 min by a similar drop (−28%) in the POM (Figure 4A). Both effects developed progressively for at least 15 min at which point the maximal inhibition of activity reached about 40%. These data thus confirm that sexual interactions result in a rapid reduction in AA and demonstrate that these enzymatic changes occur in specific brain regions.

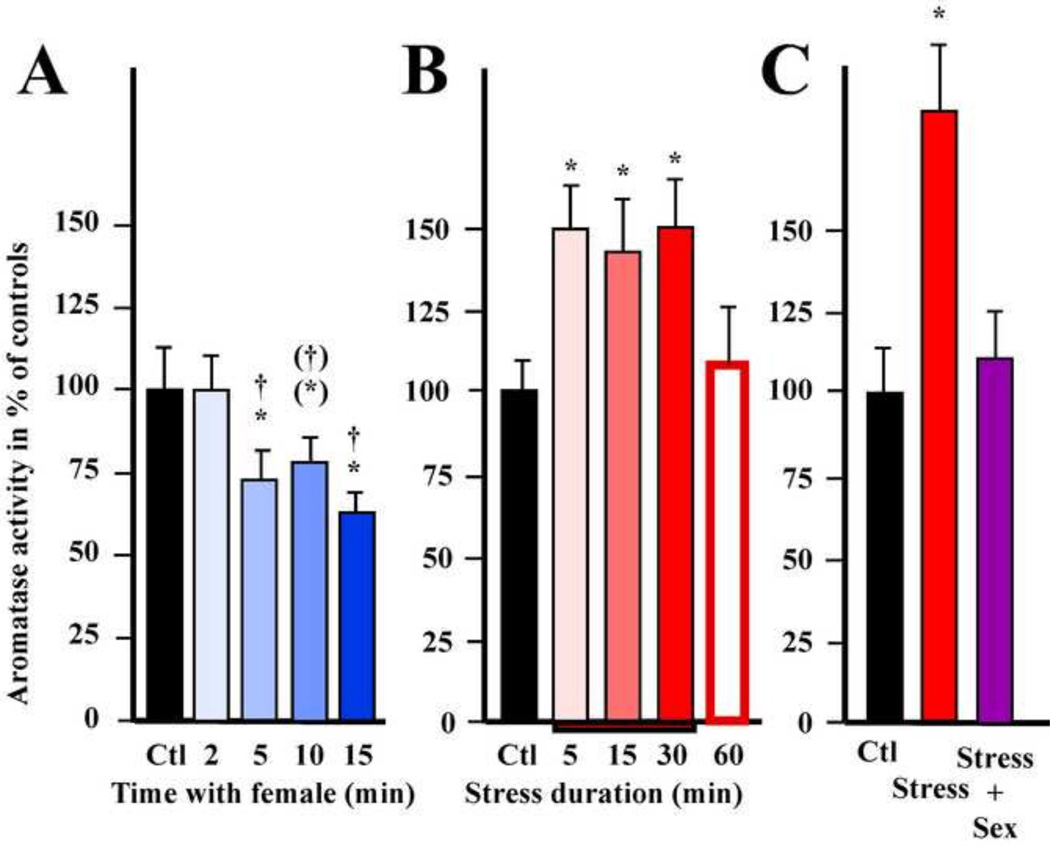

Figure 4.

Rapid changes in aromatase activity (AA) observed in the medial preoptic nucleus of male quail that have been exposed for various durations (2 to 15 min) to a female and allowed to copulate with her (A)or submitted to an acute restraint stress for 5 to 30 min, indicated by the red bar on the X axis (B) or exposed to stress for 5 min and then immediately allowed to copulate with a female (Stress+Sex) for 5 min (C). In panel B, birds exposed to restraint stress for 30 min were also sampled 30 min after the cessation of stress (time point marked 60 min). (*) and * p < 0.1 and 0.05 respectively vs Ctl (control), (†) and † p < 0.1 and 0.05 respectively vs 2 min. Redrawn from data in [65](A), [68](B) and [70](C).

The comparison of the time course of these enzymatic changes with the pattern of sexual activity displayed by these males revealed that sexual activity terminates before the drop in AA becomes detectable [65] implying that this enzymatic response is a consequence rather than the cause of changes in behavior. Moreover, submitting all subjects to 2 min long interactions (during which most of the sexual activity takes place) and collecting brains after different latencies post- copulation did not reveal any change in AA suggesting that this enzymatic down- regulation is not related to sexual performance but requires the presence of the female for a more extended period of time [65]. This conclusion is supported by the observation that simply seeing the female induces the same enzymatic response in the POM (but not in the tuberal hypothalamus) as copulation, providing further support to the idea that rapid changes in AA do not depend on behavior display but on the female's presence. Although the functional significance of such a reduction in brain aromatase activity is still debated, these data provide evidence that aromatase activity is rapidly modulated in behaviorally relevant situations in specific brain areas and in a time scale compatible with non-genomic effects of estrogens.

It must be stressed that these enzymatic changes cannot reflect local changes in testosterone or co-factor availability since all samples were incubated with the same concentration of enzymatic substrate (3H-androstenedione) and co-factor (NADPH). Therefore, such changes demonstrate either a reduction in the concentration of the enzyme due to degradation or a reduction in its catalytic ability due to post-translational modifications that are presumably similar to those described in vitro. It was recently shown that the enzymatic inhibition induced by a 5 min interaction is no longer detected 2 hours after this interaction [65] indicating that the enzymatic down-regulation unlikely relies on protein degradation (re-synthesis would take more time) but rather depends on post-translational modifications.

In male rats, sexual interactions are accompanied by a rise in extracellular glutamate concentration in the preoptic area [77]. As alluded to earlier, in rodents and birds, preoptic neurons, including aromatase neurons, are sensitive to glutamate [52; 53; 125]. It could thus be hypothesized that a female-induced rise in preoptic glutamate could result in a transient down-regulation of aromatase activity following copulation in quail. Although it is not yet known whether a similar glutamate release occurs in the avian POA, it is worth noting that in rats, glutamate controls the release of dopamine in the POA [75; 76]. Similar changes in extracellular dopamine concentration have been reported in male quail POA during copulation or visual interaction with a female [128; 129]. Only males that eventually engaged in behavior showed elevated dopamine levels but, in males who copulated, no difference in dopamine was observed between sampling periods during which copulation did or did not occur suggesting that the dopamine response is driven by the male's motivational state not by its copulatory activity [129]. Based on what is known in rodents [120], it is conceivable that these changes in extracellular dopamine concentrations in quail also reflect an increased glutamatergic release. Since glutamate was shown to inhibit AA within minutes in hypothalamic brain explants [18], these postulated changes in glutamate release would perfectly match and could explain the variations in enzymatic activity observed after sexual interactions in the quail brain.

10.2. Effect of stress

Evidence is also accumulating in support of a role for stress in the acute modulation of AA. Indeed, exposing male quail to acute restraint stress for 15 min or an acute injection of corticosterone 30 min prior to brain collection results in a significant increase in AA measured in HPOA homogenates [20]. As observed in the case of sexual interactions, the effect of stress is region-specific as the enzymatic up- regulation is detected only in the POM and to a lesser extent in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus [68]. In the POM, the increase in AA reaches 150% of control values within 5 min of stress exposure (Figure 4B). This elevated activity persists as long as the stressor is present and returns to control levels within 30 min after stress cessation. Interestingly, females also exhibit a moderate increase in AA in the POM and profound enzymatic reduction in the tuberal hypothalamus (60% of controls). In contrast to males, female responses are not as fast and are sustained beyond stressor cessation [68].

Although stress induced a significant increase in circulating corticosterone (CORT) levels, no correlation was found between individual CORT concentrations and AA measured in any brain region considered [68]. Since circulating corticosterone cannot explain by itself the sex and regional specificity of the enzymatic responses, other candidates were also considered. Experiments looking at the role of different components of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis recently suggested that CORT, arginine-vasotocin (AVT) and corticosterone-releasing factor (CRF) all play a role in the control of stress-induced changes in AA in the POM but not in other regions [69]. More work is thus warranted to unravel the mechanisms of regulation of aromatase by stress.

Interestingly, the rapid changes in AA induced by stress occur in brain nuclei that play a critical role in the control of reproduction. Although little is known about the functional implications of local changes in estrogen synthesis in brain regions other than the POA, these results suggested that rapid changes in aromatase activity might mediate acute effects of stress on behavior and fertility. Surprisingly, male or female sexual behavior was not affected by 15 min of acute restraint stress, but fertilization was slightly reduced in stressed females [70]. Stress (15 min) or copulation (5 min) alone induced the same effects on AA as previously described. Yet, when presented in sequence, sexual behavior reversed the enzymatic up- regulation induced by stress in the male POM (Figure 4C). Likewise, the stress- induced decrease in AA in the female tuberal hypothalamus (presumably homologous to the arcuate nucleus of mammals) was reversed following pairing with a male. Strikingly, a clear anatomical specificity emerged when considering the profile of response to stress and mating. In some regions, such as the male POM or the female Tuber, aromatase seems responsive to both stimuli, while the enzyme appears exclusively sensitive to one stimulus in other regions [70].

Although the functional consequences of these region-specific enzymatic changes induced by stress remain unclear (for further discussion of this issue, see [62; 68; 70]), together these data provide compelling evidence that changes in the social and environmental context induce rapid changes in AA in specific brain regions in vivo. Importantly, the fast time course and reversibility of most of these effects strongly suggest that the underlying mechanism(s) relies on post-translational modifications of the enzyme in vivo. This idea is strongly supported by the reversal within 5 min of stress-induced changes by copulation.

10.3 Social communication

10.3.1 Mechanisms of control of aromatase in the caudo-medial nidopallium (NCM)