Abstract

Rapamycin (Sirolimus®) is used to prevent rejection of transplanted organs and coronary restenosis. We reported that rapamycin induced cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury through opening of mitochondrial KATP channels. However, signaling mechanisms in rapamycin-induced cardioprotection are currently unknown. Considering that STAT3 is protective in the heart, we investigated the potential role of this transcription factor in rapamycin-induced protection against (I/R) injury. Adult male ICR mice were treated with rapamycin (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (DMSO) with/without inhibitor of JAK2 (AG-490) or STAT3 (stattic). One hour later, the hearts were subjected to I/R either in Langendorf mode or in situ ligation of left coronary artery. Additionally, primary murine cardiomyocytes were subjected to simulated ischemia/reoxygenation (SI-RO) injury in vitro. For in situ targeted knockdown of STAT3, lentiviral vector containing short hairpin RNA was injected into left ventricle 3 weeks prior to initiating I/R injury. Infarct size, cardiac function, cardiomyocyte necrosis and apoptosis were assessed. Rapamycin reduced infarct size, improved cardiac function following I/R, limited cardiomyocytes necrosis as well as apoptosis following SI-RO which were blocked by AG-490 and stattic. In situ knock-down of STAT3 attenuated rapamycin-induced protection against I/R injury. Rapamycin triggered unique cardioprotecive signaling including phosphorylation of ERK, STAT3, eNOS and glycogen synthase kinase-3β in concert with increased prosurvival Bcl-2 to Bax ratio. Our data suggest that JAK2-STAT3 signaling plays an essential role in rapamycin-induced cardioprotection. We propose that rapamycin is a novel and clinically relevant pharmacological strategy to target STAT3 activation for treatment of myocardial infarction.

1. Introduction

Rapamycin (Sirolimus®), an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), is a macrocyclic fermentation product isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopius, and has been widely used as an immunosuppressive agent for the prophylaxis of allograft rejection [1]. Due to its antiproliferative property, rapamycin prevents intimal growth of graft coronary arteries and reduces the incidence of vasculopathy [2]. Rapamycin is currently used for coating drug-eluting stents to reduce restenosis after coronary angioplasty [3]. However, the therapeutic effects of rapamycin in patients with heart failure after ischemia injury remain unclear. Previous studies report that rapamycin can abolish the cardioprotective effect of ischemic or pharmacological preconditioning [4–6]. On the contrary, We first reported that rapamycin treatment reduced infarct size after ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and also reduced attenuated necrosis and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes following simulated ischemia/reoxygenation (SI-RO) [7]. We reported that attenuation of I/R injury with rapamycin was mediated through opening of ATP-sensitive K channels (mitoKATP channel). In addition, another mTOR inhibitor, everolimus prevented left ventricular (LV) remodeling, limited infarct size, improved LV function and increased autophagy post myocardial infarction [8]. It appears that rapamycin concentrations and/or timing of its administration during I/R may contribute to such discrepant effects. Additional studies are needed to understand the differential effects of rapamycin treatment. Nevertheless, the signaling mechanisms in rapamycin-induced protection against I/R injury remain poorly understood.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) is a central component of cardioprotection [9, 10]. The activation of JAK-STAT pathway by ischemic preconditioning up-regulates iNOS and thereby contributes to adaptation of heart to ischemic stress [11, 12]. JAK-STAT pathway is comprised of a family of receptor-associated cytosolic tyrosine kinases (JAKs), that phosphorylate a tyrosine residue in cognate of STATs [13]. Phosphorylation and activation of STAT in response to ischemic preconditioning confer cardioprotection via prosurvival signaling cascades or the inhibition of proapoptotic factors [14]. The putative JAK2 inhibitor AG 490 abrogated ischemic preconditioning-induced acute cardioprotection after myocardial I/R [11]. Constitutive cardiomyocyte-restricted deletion of STAT3 has been shown to increase apoptosis [15, 16] and infarct size after I/R and cause loss of protection during ischemic postconditioning and pharmacological preconditioning [9, 17, 18]. Recent studies indicate that STAT3 is also present in the mitochondria, wherein it modulates mitochondrial respiration, regulates mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, and inhibits the opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pores (mPTP) [19–21]. A mitochondrial-targeted STAT3 overexpression in mice preserves complex 1 respiration during ischemia and reduces reactive oxygen species (ROS) production from complex I (ROS) and blocks cytochrome c release into the cytosol [22]. However, it is unknown whether rapamycin induces acute cardioprotection through activation of JAK/STAT pathway.

Thus, considering an important role of JAK-STAT3 in preconditioning and cardioprotection, we undertook this investigation to determine the potential role of this signaling pathway in rapamycin-induced protection against I/R injury. The major aims of the present study were to 1) determine whether rapamycin would reduce infarct size and improve cardiac function following in situ I/R injury; 2) demonstrate whether rapamycin would affect cardioprotective signaling components, such as STAT3 and ERK1/2; and 3) determine the functional role of STAT3 in cardioprotection with rapamycin. Our results show that rapamycin induces ERK-dependent phosphorylation of STAT3, which is causatively involved in reducing I/R injury in heart and cardiomyocytes.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male outbred CD-1 mice (body weight ~ 30 g) were supplied by Charles River Laboratories. The animal care and experiments were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University.

2.2. Experimental Groups

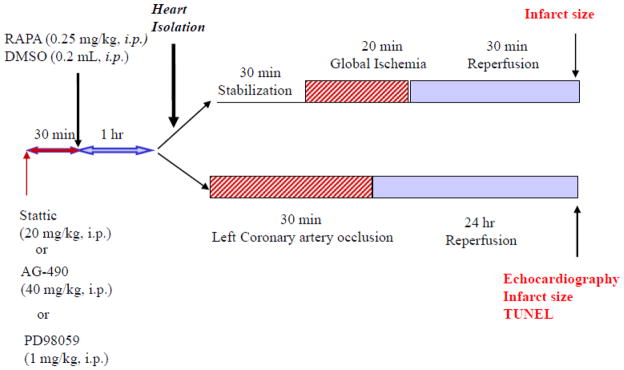

For global I/R protocol, we used six groups: mice were injected (intraperitoneal, i.p.) 1) DMSO (solvent for rapamycin, AG490- JAK inhibitor and Stattic- STAT3 inhibitor); 2) rapamycin (0.25 mg/kg), 3) rapamycin+AG490 (40 mg/kg), 4) AG490 only, 5) rapamycin+stattic (20 mg/kg), and 6) stattic only. For in vivo regional I/R protocol, we used six groups: 1) DMSO, or 2) rapamycin (0.25 mg/kg), 3) rapamycin+stattic (20 mg/kg), 4) stattic only 5) PD98059 (inhibitor of ERK, 1 mg/kg) and PD98059 only. AG490, stattic or PD98059 were injected 30 min before the administration of rapamycin (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Experimental Design.

Experimental groups and protocol of global I/R in Langendorff isolated perfused mouse heart and regional I/R by left coronary artery (LAD) occlusion in mouse heart.

2.3. Global I/R in Langendorff-perfused Mouse Heart

The methodology of isolated perfused mouse heart has been described previously in details [7, 23]. Stattic (STAT3 inhibitor; 20 mg/kg) or AG490 (JAK2 inhibitor; 40 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 30 min before rapamycin treatment (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.). After 1 hr, the animal was anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal® Sodium Solution; 100 mg/kg, 33 U heparin, i.p.) and the heart was removed and the aorta was cannulated and tied on a 20-gauge blunt needle connected to Langendorff perfusion system. The heart was perfused at a constant pressure of 55 mmHg with modified Krebs-Henseleit solution (in mM): NaCl 118, NaHCO3 24, CaCl2 2.5, KCl 4.7, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4 1.2, Glucose 11, and EDTA 0.5, continuously gassed with 95% O2+5% CO2 (pH 7.34–7.49). The buffer and heart temperature were maintained at 37°C. A force-displacement transducer (Grass, Model FT03) was attached to the apex and the resting tension of the isolated heart was adjusted to ~0.30 g. Ventricular contractile force was recorded by Powerlab 8SP computerized data acquisition system connected to the force transducer. After 30 min of stabilization, the Langendorff-perfused hearts were subjected to 20 min of no-flow global ischemia and 30 min of reperfusion (Figure 1 in supplement). Coronary flow rate was calculated by timed collection of the outflow perfusate. The hearts were not electrically paced.

2.4. Myocardial Infarction Protocol

We performed in vivo I/R studies in mouse by a previously reported method [24]. Stattic (20 mg/kg) or PD98059 (1 mg/kg, ERK inhibitor) was administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) 30 min before rapamycin treatment (0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) (Figure 1). After 1 hr of rapamycin treatment, the animals were anesthetized with the pentobarbital sodium (70 mg/kg, ip), and ventilated on a positive pressure ventilator. A left thoracotomy was performed at the fourth intercostal space, and the heart was exposed by stripping the pericardium. The LAD was occluded by a 7-0 silk ligature that was placed around it. After 30 min LAD, the air was expelled from the chest. The chest cavity was closed and the animal was placed in a cage on a heating pad until fully conscious.

2.5. Measurement of Infarct Size

After the end of reperfusion in Langendorff mode, the heart was removed, weighed and frozen at −20°C. For in vivo I/R study, the heart was removed following 30 min of ischemia and 24 hr of reperfusion, and mounted on a Langendorff apparatus. The coronary arteries were perfused with 0.9% NaCl containing 2.5 mM CaCl2 to wash out the blood, then ~2 ml of 10 % Evans blue dye were injected as a bolus. The heart was perfused with saline to wash out the excess Evans blue. Finally, the heart was removed and frozen. The frozen heart was cut into 8–10 transverse slices from apex to base of equal thickness (~1 mm). The slices were then stained by 10% tetrazolium chloride (TTC) for 30 min. The areas of infarcted tissue, the risk zone, and the whole LV were determined by computer morphomety using a Bioquant imaging software.

2.6. In situ knockdown of STAT3

In addition to the pharmacological approach, we used lentiviral expression vector containing short hairpin RNA of STAT3 (Lenti shSTAT3 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to selectively knockdown STAT3. The animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (70 mg/kg ip), intubated orotracheally and ventilated on a positive-pressure ventilator. A left thoracotomy was performed at the fourth intercostal space, and the heart was exposed by stripping the pericardium. Using 27G needles, three volumes of 10 μl each containing (0.15X106 IFU) of Lenti shSTAT3 or control Lenti shRNA (Lenti shC) were injected into the LV. After injection, the air was expelled from the chest. The animals were extubated and then received intramuscular doses of analgesia (buprenex; 0.02 mg/kg; sc) and antibiotic (Gentamicin; 0.7 mg/kg; IM, for 3 days). Three weeks later, the myocardial infarction protocol was carried out as reported previously [24]. In addition, a subset of hearts was isolated for analysis of proteins by Western analysis.

2.7. Isolation of Murine Cardiomyocytes and SI-RO

The murine ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated using an enzymatic technique as previously reported [25]. After anesthetized the mouse with sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal® Sodium Solution; 100 mg/kg, i.p.), the heart was removed and perfused in a Langendorff system with bicarbonate buffer, collagenase type II and protease type XIV. After perfusion, cardimyocytes were collected and plated on laminin coated chamber slides. The cardiomyocyetes were subjected to SI for 40 min in an ischemia buffer [25] and incubated under hypoxic conditions (1% O2 and 5% CO2) and RO for 1 or 18 hr under normoxic conditions.

2.8. Necrosis and Apoptosis Assay

Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion assay and apoptosis was determined by TUNEL staining using a kit purchased from BD Biosciences as previously reported [25]. For in vivo I/R protocol, the heart was washed out and perfused with 10% formalin solution for 5 min. The heart was stored in a 10% formalin solution. Apoptosis was assessed in the transverse sections of paraffin sections. The apoptotic index was expressed as the number of apoptotic cells of all cardiomyocytes per field. The apoptotic rate in the peri-infarct regions was calculated using 10 random fields, which virtually comprised most of the peri-infarct area [24].

2.9. Doppler Echocardiography

Doppler echocardiography was performed using the Vevo770 imaging system (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) before and after 30 min regional ischemia and 24 hr reperfusion in light anesthetized mouse with pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal® Sodium Solution; 30 mg/kg, i.p.) as reported previously [24]. M-mode images of the LV were obtained, and systolic and diastolic wall thickness (anterior and posterior) and LV end-systolic and end-diastolic diameters (LVESD and LVEDD, respectively) were measured. LV fractional shortening (FS) was calculated as (LVEDD − LVESD)/LVEDD·100. Ejection fraction (EF) was calculated using the Teichholz formula.

2.10. Western Blots

Total soluble protein was extracted from the whole heart tissue with extraction buffer and protein (50 μg) from each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane [23, 25, 26]. The membrane was incubated overnight with primary antibody (phosphor-tyrosine705-STAT3, STAT3, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-P38, p38, eNOS, iNOS, BAX, BCl2 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; p-GSK3β, GSK3β, phospho-serine1177-eNOS from Cell Signaling). The membrane was washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody and the blots were developed using a chemiluminescent system (ECL Plus; Amersham Biosciences).

2.11. Data Analysis and Statistics

Data are presented as mean±S.E.M. The differences between groups were analyzed with one-way analysis of variance followed by Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test for pair-wise comparison, p<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibition of JAK/STAT3 abolishes rapamycin-induced cardioprotection

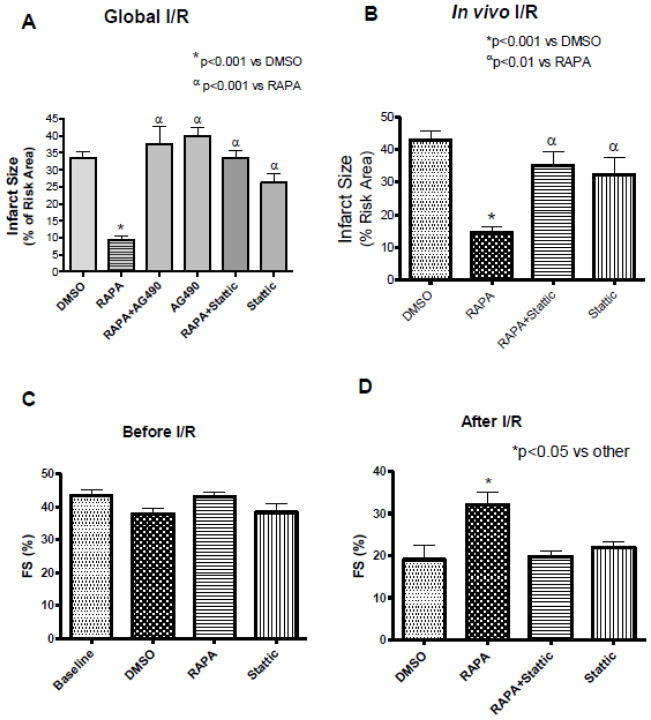

Pretreatment with rapamycin reduced infarct size (% risk area) to 9.42±1.22 compared with DMSO control 33.52±1.75 (n=7, p<0.001) following global I/R in Langendorff mode (Figure 2A). This infarct-limiting effect was abolished by AG490 (37.58±5.15%) and stattic (33.35±2.16%), whereas treatment with AG490 (39.89±2.43%) and stattic (26.17±2.84%) alone had no effect on infarct size as compared to control. The contractile function and post-ischemic coronary flow rate did not statistically alter compared with control (supplement Figure 1A and B).

Figure 2. Inhibitors of JAK and STAT3 Abolish Infarct-limiting Effect of Rapamycin (RAPA) following I/R.

(A) Myocardial infarct size following global I/R, *p<0.001 versus DMSO; αp<0.001 versus RAPA, n=7 per group. (B) Myocardial infarct size following in situ I/R. *p<0.001 versus DMSO; αp<0.01 versus RAPA, n=6 per group. Cardiac function (Fractional Shortening, FS) were measured using Doppler echocardiography (C) before I/R and (D) following in situ I/R. *p<0.05 versus DMSO; n=5 per group. See Figure 1 for drug treatment schedules and I/R protocol.

In the in vivo I/R, the infarct size was reduced from 43.03±2.48% in the DMSO treated group to 14.73±1.81% in rapamycin-treated mice (n=6, p<0.001) (Figure 2B). The infarct-sparing effect of rapamycin was abolished with stattic (35.00±4.34%). Mice treated with stattic (32.34±5.29%) alone had no effect on infarct size compared to DMSO group (n=6, p>0.05). The risk areas (% LV) were not statistically different between groups (supplement Figure 2A).

Cardiac function was assessed by echocardiography after rapamycin (1 hr) or stattic (30 min) treatment. Rapamycin and stattic did not alter fractional shortening (FS) compared to baseline and DMSO control (Figure 2C). After 30 min LAD occlusion and 24 hr reperfusion, DMSO treated control mice showed significant reduction in FS, 19.06±3.41% and EF, 41.2±6.48% compared to DMSO treated control mice before I/R (FS, 37.8±1.82% and EF, 66.0±5.86%) (n=5, p<0.05, Figure 2D and supplement Figure 2D). Rapamycin improved FS (32±3.21%) and EF (66±5.86%) compared with DMSO treated control mice after I/R (n=5, p<0.05, Figures 2D, and supplement Figure 2D). Stattic abolished the functional improvement induced by rapamycin after I/R (FS, 19.50±1.55%; EF, 47.0±3.48%). Stattic alone was similar to DMSO control (p>0.05).

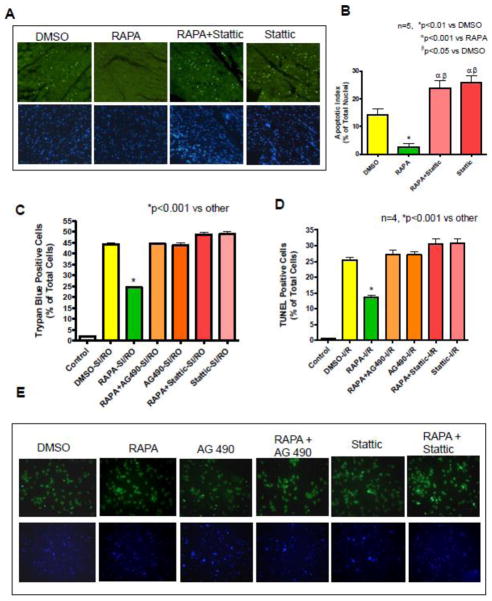

3.2. Effect of STAT3 Inhibition on Myocardial Apoptosis

Rapamycin reduced TUNEL-positive nuclei in the peri-infarct regions to 2.64±1.29% as compared to DMSO (14.32±2.20%) after in vivo I/R (Figure 3 A, B). Stattic treatment blocked rapamycin-induced reduction of apoptosis (23.84±2.68%).

Figure 3. Effects of STAT3 Inhibition on Myocardial Apoptosis.

Myocardial apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay after in vivo I/R. (A) Representative images of TUNEL-positive nuclei in green fluorescent color and total nuclei staining with 4,5-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). (B) Bar diagram showing quantitative data of TUNEL positive nuclei in myocardium. *p<0.01 versus DMSO; αp<0.001 versus RAPA, βp<0.001 versus DMSO, n=5 per group. (C) Cardiomyocytes necrosis was determined by trypan blue staining following 40 min simulated ischemia (SI) and 1 hr reoxygenation (RO). *p<0.001 versus other, n=4 per group. Cardiomyocytes apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay after 40 min SI and 18 hr RO. (D) Bar diagram showing quantitative data of TUNEL. *p<0.001 versus other, n=4 per group. (E) Representative images of TUNEL-positive nuclei in green fluorescent color and total nuclei staining with 4,5-diamino-2-phenylindole. See Figure 1 for drug treatment schedules and I/R protocol.

We further evaluated the role of STAT3 in the inhibition of apoptosis and necrosis with rapamycin. Primary cardiomyocytes were treated with rapamycin (100 nM) for 1 hr in the presence or absence of AG490 (20 μM) or stattic (100 μM). Cardiomyocyte necrosis was increased to 44.35±0.59% as compared with 2.00±0.40% in non-ischemic controls (Figure 3C). Treatment with rapamycin reduced the percentage of necrosis to 24.61±0.45 compared to DMSO (44.35±0.59, n=4, p<0.001) (Figure 3C). Both AG490 and stattic abolished the protective effect of rapamycin without further effect on cell death in cardiomyocytes after SI-RO. Moreover, apoptosis increased from 0.72±0.12% (non-ischemic control) to 25.37±1.05% of total cells with SI-RO (p<0.001 n=4, Figure 3D, E), which was reduced by rapamycin to 13.67±0.72% (n=4, p<0.001). AG490 and stattic blocked rapamycin’s anti-apoptotic effect and alone did not influence the control group.

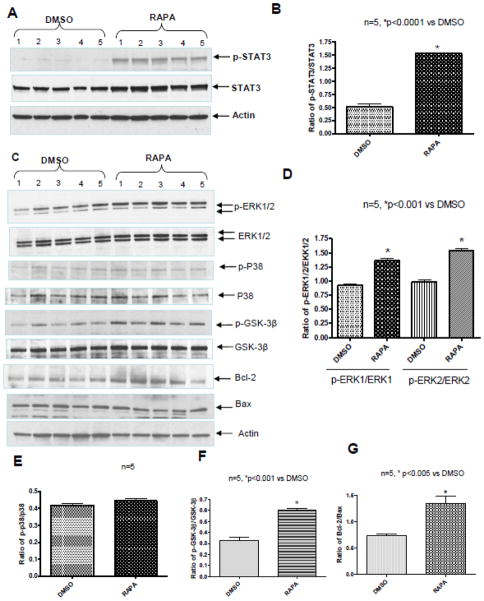

3.3. Rapamycin Increases STAT3 and ERK Phosphorylation

Rapamycin induced STAT3 phosphorylation at tyrosine 705 in heart compared to DMSO control after 1 hr of treatment (Figure 4A and B, n=5, p<0.0001). This time frame is adequate for nuclear translocation and transactivation potential of STAT3 [21]. Rapamycin didn’t alter total STAT3 compared to DMSO control (Supplement Figure 3A). Rapamycin also induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 after 1 hr of treatment compared with control (Figure 4C and D, n=5, p<0.001), but had no effect on p38 phosphorylation (Figure 4C and E). The phosphorylation of GSK-3β at Ser9 (which inactivates GSK-3β) was enhanced after rapamycin treatment compared to control (Figure 4C and F; n=5 p<0.001). The expression of Bax was significantly reduced in heart following 1 hr of treatment with rapamycin as compared with DMSO, while Bcl-2 was increased (Figure 4C, supplement figure 3B and C; n=5, p<0.005). Consequently, the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax was increased with rapamycin as compared to DMSO (Figure 4G; n=5, P<0.005).

Figure 4. Rapamycin (RAPA) Enhances Phosphorylation of STAT3, ERK and GSK-3β.

(A) Representative immunoblots for p-STAT3, total STAT3 and Actin expression in whole heart after 1 hr of RAPA treatment. (B) Densitometry analysis of immunoblots for the ratio of p-STAT3/STAT3. *p<0.0001 versus DMSO, n=5 per group. (C) Representative immunoblots showing the phosphorylation of ERK, p38, GSK-3β and the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax in heart, (D) Densitometric analysis of p-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 and (E) p-p38/p38, and (F) p-GSK-3β/GSK-3β, *p<0.001 versus DMSO. (G) Densitometric analysis of the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax. *p<0.005 versus DMSO; n=5 per group.

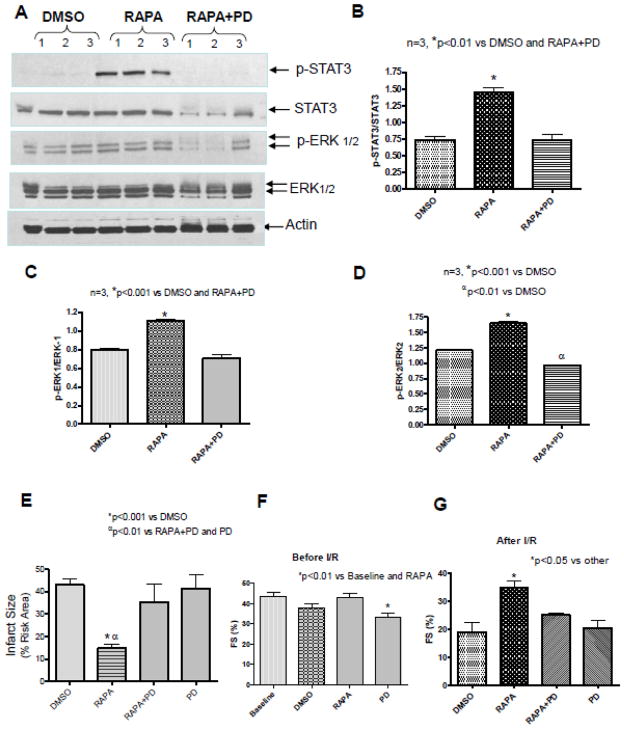

3.4. Inhibition of ERK blocks rapamycin-induced cardioprotection

Treatment with ERK inhibitor, PD98059 inhibited rapamycin-induced phosphorylation of ERK (Figure 5A, C, D). Interestingly, rapamycin-induced STAT3 phosphorylation was also abolished by PD98059 (Figure 5A and B, n=3, p<0.01). PD98059 also reduced the expression of total STAT3 and ERK compared to Actin. The infarct-limiting effect of rapamycin (14.73±1.81%) was abolished by PD98059 (35.22±8.32%), whereas treatment with PD alone (41.48±5.87%) had no effect on infarct size as compared to control (43.03±2.48%) (Figure 5E). The risk areas (% LV) were not statistically different between groups (Supplement Figure 2A).

Figure 5. ERK Inhibition Reduces Rapamycin-induced Phosphorylation of STAT3 and ERK.

(A) Representative immunoblots for p-STAT3, STAT3, pERK1/2, ERK1/2 and Actin in whole heart after 1hr of treatment with RAPA and/or PD 98059. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots for the ratio of (B) p-STAT3/STAT3, *p<0.01 versus DMSO and RAPA+PD, (C) p-ERK1/ERK1, *p<0.001 versus DMSO and RAPA+PD and (D) p-ERK2/ERK2, *p<0.001 versus DMSO, αp<0.01 versus RAPA+PD. n=3 per group. (E) Myocardial infarct size following in situ I/R. *p<0.001 versus DMSO; αp<0.01 versus RAPA+PD and PD alone, n=6 per DMSO and RAPA and n=4 for PD and RAPA+PD groups. (F) Fractional Shortening (FS) before I/R protocol, *p<0.01 vs baseline and RAPA, and (G) FS following in situ I/R. *p<0.05 versus DMSO; n=5 per group. See Figure 1 for drug treatment schedules and I/R protocol.

Before I/R, PD98059 treatment for 30 min significantly reduced FS compared to baseline and RAPA (n=5, p<0.01) (Figure 5F). After I/R, rapamycin-induced functional improvement (FS, 32±3.21% and EF, 66±5.86%) was also blocked with PD98059 treatment (FS, 25.0±0.71%, EF, 51.0±1.3%) (Figure 5G and supplement figure 2D). PD98059 alone has similar function as DMSO control.

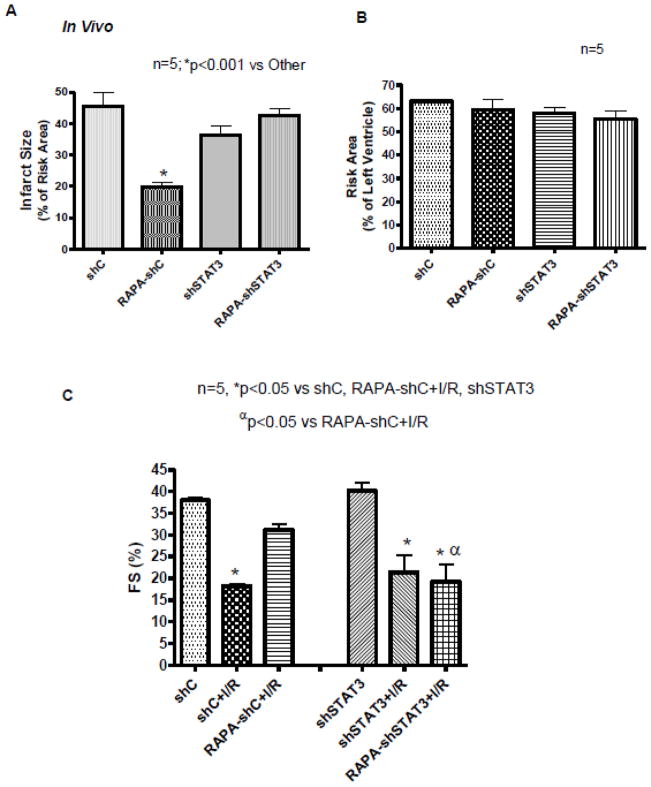

3.5. STAT3 Knock-down Abolishes Infarct-limiting Effect of Rapamycin

A 56% decrease in STAT3 expression was observed in the heart after 3 weeks of left intra-myocardial injection of lenti-shSTAT3 as compared with control virus lenti-shC (supplement Figure 3D and E). Subjecting the hearts to in vivo I/R demonstrated reduction of infarct size with rapamycin treatment (19.73±1.63) as compared with DMSO (45.55±4.36) in mice infected with control virus, lenti-shC (n=6, p<0.001, Figure 6A). However, the infarct-sparing effect of rapamycin was blunted after knock-down of STAT3 as shown by increase in infarct size to 42.56±2.06. There was no difference in infarct size between DMSO-treated shC and shSTAT3 groups (n=5, p>0.05). The risk areas were not different between the groups (Figure 6B). Knock-down of STAT3 did not alter cardiac function before or after I/R compared to shC (Figure 6C). However, after I/R, rapamycin improved function in shC-treated mice (FS, 31±1.4%, EF, 59±2.58% compared to control FS, 18.2±0.49%, EF, 37.5±1.19%), but that was blocked in shSTAT3-treated mice (FS, 19±3.99%, EF, 39±10.13%) (n=5, p<0.05; Figure 6C and Supplement Figure 3F).

Figure 6. STAT3 Knock-down Abolishes Infarct-limiting Effect of Rapamycin (RAPA) following in situ I/R.

(A) Myocardial infarction and (B) Risk area were determined after regional I/R protocol. *p<0.001 versus other, n=5 per group. (C) Fractional Shortening (FS) before I/R and following in situ I/R. *p<0.05 versus shC, shSTAT3 and shC-RAPA+I/R; αp<0.05 versus shC-RAPA+I/R; n=5 per group.

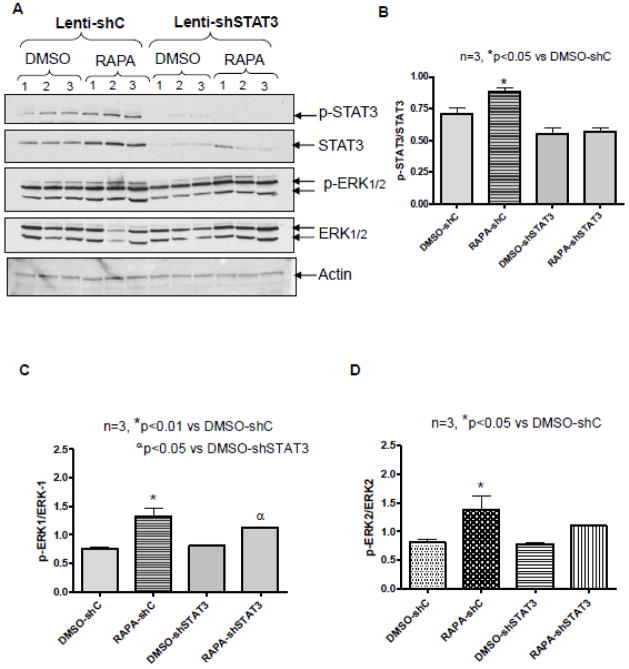

3.6. Effect of STAT3 Knock-down on ERK Phosphorylation

To demonstrate the relationship between ERK and STAT3 phosphorylation in rapamycin-induced cardioprotection, we analyzed LV samples from lenti-shSTAT3 and lenti-shC-infected hearts. The results showed phosphorylation of STAT3 (p<0.05, n=3) and ERK (p<0.01, n=3) significantly induced in lentis-shC infected hearts after rapamycin treatment (as expected) (Figure 7). However, rapamycin did not enhance STAT3 phosphorylation in the shSTAT3-infected group (Figure 7A and B). Interestingly, rapamycin still enhanced the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in the shSTAT3-infected group (Figure 7A, 7C and D). The expression of Bcl-2 was significantly induced in shC group after rapamycin treatment before I/R (p<0.05, n=3), but remained unchanged after I/R (Supplement Figure 4 A,B and Supplement Figure 5 A,B). Rapamycin did not significantly reduce the expression of Bax before or after I/R (Supplement Figure 4 A, B and Supplement Figure 5C, D). As a result, rapamycin significantly induced the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax in shC group before I/R (p<0.05, n=3), but not following I/R (Supplement Figure 4C, D). Interestingly, the expression of Bcl-2 was suppressed after STAT3 knockdown and rapamycin failed to reinstate. STAT3 knockdown had no effect on Bax expression, and consequently, the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax did not change significantly after rapamycin treatment in STAT3 knockdown group as compared to shC group after I/R (Supplement Figure 4 D).

Figure 7. STAT3 Knock-down does not alter ERK Phosphorylation in heart.

Representative immunoblots of p-STAT3, STAT3, pERK1/2, and ERK from hearts infected with lenti-shC or lenti-shSTAT3 following rapamycin treatment. Densitometric analysis of (B) p-STAT3/STAT3, *p<0.05 versus DMSO-shC, (C) p-ERK1/ERK1, *p<0.01 versus DMSO-shC, αp<0.05 versus DMSO-shSTAT3, and (D) p-ERK2/ERK2, *p<0.05 versus DMSO-shC. n=3 per group.

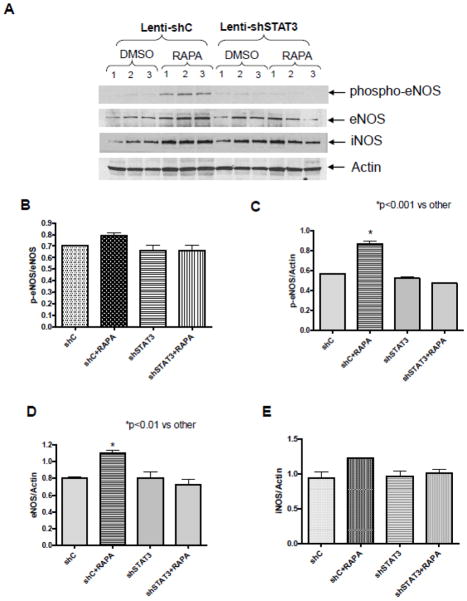

3.7. STAT3 Knock-down inhibits eNOS/iNOS

eNOS expression and its phosphorylation were significantly increased after rapamycin treatment in hearts infected with lenti-shC (Figure 8A, B, C, D). Rapamycin also increased the ratio of p-eNOS to total eNOS, but it is not significant due to the significant increase of total eNOS in shC-treated mice. Real-time PCR also confirmed the significant increase of eNOS transcript level after 1 hr treatment with rapamycin in control mice (supplement figure 6). Rapamycin treatment had no significant effect on iNOS expression (Figure 8E). The increased expression and phosphorylation of eNOS following rapamycin treatment was inhibited in hearts with STAT3 knockdown (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Effect of STAT3 Knock-down on eNOS/iNOS in heart.

(A) Representative immunoblots of phospho-eNOS, eNOS, iNOS, and Actin in hearts (infected with lenti-shC or lenti-shSTAT3) after 1 hr of treatment with rapamycin. Densitometric analysis of (B) p-eNOS/eNOS (C) p-eNOS/Actin, (D) eNOS/Actin and (E) iNOS/Actin. *p<0.01 versus control shC, n=3 per group.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the signaling pathways by which rapamycin triggers preconditioning-like anti-infarct effect following I/R injury in mouse heart. Specifically, we focused on the potential role of JAK2-STAT3 pathway in rapamycin-induced protection. This is because inactivation of STAT3 or deletion of STAT3 appears to be a key event in the diminution of cardioprotection in response to various physiological stresses including I/R [9, 10, 27]. Moreover, it has been shown that mice with a cardiomyocyte-restricted deletion of STAT3 develop spontaneous heart failure in response to stress [15–17]. Our results demonstrate that rapamycin caused significant reduction in infarct size following ex vivo and in situ I/R injury in mice. Such cardioprotective effect of rapamycin was associated with significant increase in phosphorylation of STAT3. Pharmacological inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 and targeted in vivo knockdown of STAT3 using lenti-shRNA abolished the infarct-limiting effect of rapamycin against I/R injury. Stattic also blocked rapamycin-induced preservation of LV function and reduction of apoptosis 24 hr after I/R. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which demonstrates that the modulation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway is an essential role in pharmacological preconditioning with rapamycin.

Previous studies showed conflicting results about the critical role of mTOR and the therapeutic effect of its inhibitor (rapamycin) in regulating I/R injury. Several studies reported that rapamycin or its analogs abolished the cardioporotective effect of insulin infusion after I/R injury [4, 28]. Rapamycin has also been shown to block the protective effect of ischemic or pharmacological preconditioning [5, 29]. More recently, Herbabdez et a. reported that rapamycin treatment increased infarct size at 24 hr post-I/R in vivo and accelerated cell death induced by oxidative stress in cardiomyocyte in vitro [30]. In contrast, Buss et al. reported that inhibition of mTOR with everlimus reduced infarct size in chronic MI model [8]. Moreover, we also demonstrated rapamycin decreased infarct size in a Langendorff I/R model [7]. The reason for these opposing results is not clear. However, it appears that rapamycin concentration and timing of its administration during I/R may contribute such opposing effects. A cardioprotective effect of rapamycin was observed if the heart is pretreated with rapamycin prior to I/R [7]; however, if rapamycin is administered just prior to the onset of reperfusion [4], the preconditioning-mediated protective effect is lost.

mTOR exists in two functionally distinct complexes referred to as mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTORC2, which were originally defined as being rapamycin-sensitive and -insensitive, respectively [31]. mTOR is critical for the induction of cardiac hypertrophy after stress, and inhibiting this kinase improves the heart function in pathological settings [32]. In mice and rats, mTOR inhibition with rapamycin regressed remodeling by pressure overload and blunted the development of cardiac dysfunction [33–35]. In contrast, mTOR deletion caused lethal, dilated cardiomyopathy that was sufficient to induce the development of heart failure [36]. A recent study also demonstrated that mTOR overexpression provided substantial cardioprotection against I/R injury and suppressed the inflammatory response in cardiac-specific mTOR transgenic mice [37]. Interestingly, in this study, S6 phosphorylation (by mTORC1) was increased compared with baseline, whereas no change in Akt phosphorylation (by mTORC2) was observed, suggesting that mTORC1 is the dominant complex stimulated after I/R injury [37]. One possible explanation for the discrepancy between the use of pharmacological mTOR inhibitors and transgenic mice might be in the fact that rapamycin inhibits mTOR2 only with extensive treatment, whereas mTOR deletion or overexpression affect both complexes. Rapamycin may inhibit mTORC1 without altering its stoichiometry, whereas mTOR knockout does alter stoichiometry [36]. Further investigation is required to understand the mechanism underlying the differential effect of rapamycin treatment.

In the present study, the inhibition of STAT3 sensitized the heart to apoptotic cell death following I/R injury. In adult cardiomyocytes, stattic and AG490 abolished rapamycin-induced protection against necrosis and apoptosis following SI-RO (Figure 3). STAT3 has been reported to be necessary for cardioprotective effects such as preservation of LV functional reserve and perfused capillary density, reduced apoptotic cell death and limitation of infarct size by ischemic or pharmacological preconditioning approaches [38, 39]. In a clinically relevant in situ pig model of regional myocardial I/R, the infarct size reduction by ischemic postconditioning was mediated by activation of mitochondrial STAT3 along with preservation of mitochondrial complex I respiration and calcium retention capacity [20]. Our results also show that rapamycin reduced pro-apoptotic protein Bax and induced anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, therefore caused a significant increase in the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax. Interestingly, the expression of Bcl-2 was suppressed after STAT3 knockdown and rapamycin failed to induce. STAT3 knockdown had no effect on Bax expression, and subsequently, rapamycin treatment did not change the ratio of Bcl-2 to Bax after STAT3 knockdown. It has been shown that antiapoptotic signals are transduced via STAT3 in the myocardial response to multiple insults by upregulation of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL or downregulation of Bax [40]. STAT3 activation is important in inhibiting both the death receptor pathway (which is modulated by c-FLIPL/S) and the mitochondrial pathway (which is mediated by Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL)[10].

The present study also revealed that rapamycin significantly increased the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, without altering the phosphorylation of p38. ERK has been reported to be involved in serine phosphorylation of STAT3 [41, 42]. It has been suggested that JAK/STAT activation is upstream of ERK because the JAK/STAT inhibitor decreased the phosphorylation of ERK, and inhibition of ERK had no effect on the phosphorylation of STAT3 [43, 44]. Our results show that PD98059 significantly reduced rapamycin-induced phosphorylation of ERK and STAT3 (Tyr-705), whereas knock-down of STAT3 did not affect rapamycin-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2. Although previous studies clearly demonstrated serine phosphorylation of STAT3 regulates ERK, the current results indicate that ERK may also phosphorylate tyrosine on STAT3.

We next asked the question whether activation of GSK3β plays a role in cardioprotection with rapamycin. GSK3β is a multifunctional kinase, widely distributed in many cellular compartments and serving a multitude of cellular functions. Although, some undesired effects may result from chronic application of GSK3β inhibitors [45], GSK3β inhibition has been proposed as an essential mechanism for cardioprotection [46, 47]. Ras activation of ERK1/2 can also lead to phosphorylation and inhibition of GSK3β [48, 49]. GSK3β also promotes apoptosis by degradation of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins by ubiquitin proteasome pathway and facilitating cytochrome c release [50]. It has been shown that activation of GSK3β induces myocardial apoptosis and GSK3β becomes inactivated when phosphorylated at Ser9 [51]. Suppression of GSK3β mediates cardioprotection during I/R by regulating the mPTP opening through direct phosphorylation, thereby inducing mitochondrial depolarization release of cytocrorm c, and eventual cell death [46]. More recently, it was shown that inhibition of GSK3β transfers cytoprotective signaling through mitochondrial Cx43 onto mitoKATP channels [52], the opening of which has been linked with rapamycin-induced cardioprotection as we reported previously [7]. Recent study suggested that the activity of GSK3β is differentially regulated by ischemia and I/R. GSK3β is dephosphorylated and activated by prolonged ischemia (2hr) but is phosphorylated and inhibited by I/R (10 min/2hr) [6]. GSK3β was suggested to be the critical upstream regulator of mTOR during both prolonged ischemia and reperfusion in the heart. Interestingly, the enhancement of myocardial injury in response to prolonged ischemia by suppression of GSK3β was reversed by rapamycin. Furthermore, the suppression of reperfusion injury by inhibition of GSK3β during I/R was also attenuated by rapamycin. Vigneron et al. also showed that down-regulation of GSK3β activates mTOR pathway and induces cardioprotection in ischemic or pharmacological preconditioning model and that protection was inhibited by rapamycin [53]. In the present study, we observed that rapamycin caused significant increase in the phosphorylation of GSK-3β at Ser9 (Figure 4C and F). Previous study showed that opioid-induced cardioprotection occurs via the phosphorylation of JAK2 and STAT3, which, in turn, regulates PI3K-dependent proteins Akt and GSK-3β [18]. We also predict that ERK activates STAT3 and inhibits downstream GSK3β (by phosphorylating ser9 residue) which may mediate rapamycin-induced cardioprotection by enhancing Bcl-2/Bax ratio.

Another interesting and novel observation in the present study is that rapamycin enhanced STAT3-dependent myocardial expression and phosphorylation of eNOS (Figure 8). Previous studies have demonstrated that rapamycin treatment over 10 weeks significantly increased eNOS expression in ApoE−/− mice [54]. It is noteworthy that these studies were done with chronic treatment of rapamycin whereas the present effects of rapamycin on STAT3-dependent eNOS regulation were observed following one hour of treatment.

The mechanism(s) by which STAT3 signaling enhances the expression of eNOS in endothelial cells has recently been suggested [55]. There are 3 pools of eNOS located within the cell; (1) the perinuclear Golgi complex, (2) the plasma membrane, and (3) a cytosolic compartment. eNOS can traffic between these compartments, and subcellular targeting can affect NO production in response to various stimuli [56]. It has been proposed that after activation, STAT3 dimerizes and translocates into the nucleus, where it modulates the expression of gene targets, including NOSTRIN (eNOS traffic inducer). NOSTRIN facilitates eNOS trafficking and its correct subcellular localization [55]. A recent study also demonstrated that STAT3 regulates NO bioavailability by regulating ADMA (asymmetric dimethylarginine), inhibitor of eNOS through suppression of miR-199a-5p in rat cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells [57]. In the present study we have not provided direct causative role of eNOS in rapamycin protection against I/R injury. However, there is ample evidence in the literature which suggests that NO derived from these enzymes plays a role in preconditioning [58, 59]. Moreover, eNOS exerts cardioprotective effects by triggering the activation of protein kinase C-ERK-STAT3 pathway [60].

In conclusion, we have provided direct evidence for the essential role of JAK2-STAT3 signaling in rapamycin-induced protection against I/R injury. Our results show that rapamycin induced phosphorylation of ERK and STAT3, STAT3-dependent eNOS expression as well as phosphorylation, with upregulation of the prosurvival Bcl-2/Bax expression and inactivation of GSK-3β (Supplement Figure 7). These studies provide novel mechanistic insights into rapamycin-induced cardioprotection, which may help in expanding the therapeutic utility of this drug in limiting myocardial infarction and apoptosis following I/R injury, in addition to its current use in drug-eluting stents to reduce coronary restenosis. Nevertheless, further studies are required to demonstrate the cardioprotective effect of rapamycin when given at the time of reperfusion.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Rapamycin induced cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury

STAT3 is essential in rapamycin-induced cardioprotection

Rapamycin phosphorylate ERK, STAT3, eNOS amd GSK3β

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (HL51045, HL79424, and HL93685 to R.C.K); and American Heart Association Mid-Atlantic Affiliate Beginning Grant-in-Aid (0765273U to A.D.), National Scientist Development Grant (10SDG3770011 to F.N. S) and A.D. Williams Grant (to A.D.). We thank Eric Mayton for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Disclosures. None declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Morris RE. Prevention and treatment of allograft rejection in vivo by rapamycin: molecular and cellular mechanisms of action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;685:68–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb35853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delgado JF, Manito N, Segovia J, Almenar L, Arizon JM, Camprecios M, et al. The use of proliferation signal inhibitors in the prevention and treatment of allograft vasculopathy in heart transplantation. Transplant Rev (Orlando ) 2009;23:69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, Fajadet J, Ban HE, Perin M, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonassen AK, Sack MN, Mjos OD, Yellon DM. Myocardial protection by insulin at reperfusion requires early administration and is mediated via Akt and p70s6 kinase cell-survival signaling. Circ Res. 2001;89:1191–8. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kis A, Yellon DM, Baxter GF. Second window of protection following myocardial preconditioning: an essential role for PI3 kinase and p70S6 kinase. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1063–71. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(03)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhai P, Sciarretta S, Galeotti J, Volpe M, Sadoshima J. Differential roles of GSK-3beta during myocardial ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion. Circ Res. 2011;109:502–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan S, Salloum F, Das A, Xi L, Vetrovec GW, Kukreja RC. Rapamycin confers preconditioning-like protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in isolated mouse heart and cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buss SJ, Muenz S, Riffel JH, Malekar P, Hagenmueller M, Weiss CS, et al. Beneficial effects of Mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2435–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boengler K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Drexler H, Heusch G, Schulz R. The myocardial JAK/STAT pathway: from protection to failure. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;120:172–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolli R, Stein AB, Guo YR, Wang OL, Rokosh G, Dawn B, et al. A murine model of inducible, cardiac-specific deletion of STAT3: Its use to determine the role of STAT3 in the upregulation of cardioprotective proteins by ischemic preconditioning. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2011;50:589–97. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xuan YT, Guo Y, Han H, Zhu Y, Bolli R. An essential role of the JAK-STAT pathway in ischemic preconditioning. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:9050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161283798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawn B, Xuan YT, Guo Y, Rezazadeh A, Stein AB, Hunt G, et al. IL-6 plays an obligatory role in late preconditioning via JAK-STAT signaling and upregulation of iNOS and COX-2. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers MG., Jr Cell biology. Moonlighting in mitochondria. Science. 2009;323:723–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1169660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suleman N, Somers S, Smith R, Opie LH, Lecour SC. Dual activation of STAT-3 and Akt is required during the trigger phase of ischaemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:127–33. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Hilfiker A, Fuchs M, Kaminski K, Schaefer A, Schieffer B, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is required for myocardial capillary growth, control of interstitial matrix deposition, and heart protection from ischemic injury. Circ Res. 2004;95:187–95. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000134921.50377.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacoby JJ, Kalinowski A, Liu MG, Zhang SS, Gao Q, Chai GX, et al. Cardiomyocyte-restricted knockout of STAT3 results in higher sensitivity to inflammation, cardiac fibrosis, and heart failure with advanced age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12929–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134694100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boengler K, Buechert A, Heinen Y, Roeskes C, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Heusch G, et al. Cardioprotection by ischemic postconditioning is lost in aged and STAT3-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2008;102:131–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gross ER, Hsu AK, Gross GJ. The JAK/STAT pathway is essential for opioid-induced cardioprotection: JAK2 as a mediator of STAT3, Akt, and GSK-3 beta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H827–H834. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00003.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boengler K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Heusch G, Schulz R. Inhibition of permeability transition pore opening by mitochondrial STAT3 and its role in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:771–85. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heusch G, Musiolik J, Gedik N, Skyschally A. Mitochondrial STAT3 Activation and Cardioprotection by Ischemic Postconditioning in Pigs With Regional Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion. Circulation Research. 2011;109:1302–U279. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wegrzyn J, Potla R, Chwae YJ, Sepuri NB, Zhang Q, Koeck T, et al. Function of mitochondrial Stat3 in cellular respiration. Science. 2009;323:793–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1164551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szczepanek K, Chen Q, Derecka M, Salloum FN, Zhang Q, Szelag M, et al. Mitochondrial-targeted Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) protects against ischemia-induced changes in the electron transport chain and the generation of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:29610–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.226209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das A, Salloum FN, Xi L, Rao YJ, Kukreja RC. ERK phosphorylation mediates sildenafil-induced myocardial protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1236–H1243. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00100.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salloum FN, Abbate A, Das A, Houser JE, Mudrick CA, Qureshi IZ, et al. Sildenafil (Viagra) attenuates ischemic cardiomyopathy and improves left ventricular function in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1398–H1406. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91438.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das A, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor sildenafil preconditions adult cardiac myocytes against necrosis and apoptosis. Essential role of nitric oxide signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12944–55. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das A, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Protein kinase G-dependent cardioprotective mechanism of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition involves phosphorylation of ERK and GSK3beta. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29572–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801547200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry SP, Townsend PA, McCormick J, Knight RA, Scarabelli TM, Latchman DS, et al. STAT3 deletion sensitizes cells to oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;385:324–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuglesteg BN, Tiron C, Jonassen AK, Mjos OD, Ytrehus K. Pretreatment with insulin before ischaemia reduces infarct size in Langendorff-perfused rat hearts. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;195:273–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hausenloy DJ, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. Cross-talk between the survival kinases during early reperfusion: its contribution to ischemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:305–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez G, Lal H, Fidalgo M, Guerrero A, Zalvide J, Force T, et al. A novel cardioprotective p38-MAPK/mTOR pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:2938–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, Sengupta S, Sheen JH, Hsu PP, Bagley AF, et al. Prolonged rapamycin treatment inhibits mTORC2 assembly and Akt/PKB. Mol Cell. 2006;22:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boluyt MO, Zheng JS, Younes A, Long X, O’Neill L, Silverman H, et al. Rapamycin inhibits alpha 1-adrenergic receptor-stimulated cardiac myocyte hypertrophy but not activation of hypertrophy-associated genes. Evidence for involvement of p70 S6 kinase. Circ Res. 1997;81:176–86. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao XM, Wong G, Wang B, Kiriazis H, Moore XL, Su YD, et al. Inhibition of mTOR reduces chronic pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1663–70. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000239304.01496.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMullen JR, Sherwood MC, Tarnavski O, Zhang L, Dorfman AL, Shioi T, et al. Inhibition of mTOR signaling with rapamycin regresses established cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload. Circulation. 2004;109:3050–5. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130641.08705.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shioi T, McMullen JR, Tarnavski O, Converso K, Sherwood MC, Manning WJ, et al. Rapamycin attenuates load-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circulation. 2003;107:1664–70. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000057979.36322.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang D, Contu R, Latronico MV, Zhang J, Rizzi R, Catalucci D, et al. MTORC1 regulates cardiac function and myocyte survival through 4E-BP1 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2805–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI43008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoyagi T, Kusakari Y, Xiao CY, Inouye BT, Takahashi M, Scherrer-Crosbie M, et al. Cardiac mTOR protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H75–H85. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00241.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer P, Hilfiker-Kleiner D. Survival pathways in hypertrophy and heart failure: the gp130-STAT axis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102:393–411. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0674-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith RM, Suleman N, Lacerda L, Opie LH, Akira S, Chien KR, et al. Genetic depletion of cardiac myocyte STAT-3 abolishes classical preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;63:611–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Negoro S, Kunisada K, Tone E, Funamoto M, Oh H, Kishimoto T, et al. Activation of JAK/STAT pathway transduces cytoprotective signal in rat acute myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trimarchi T, Pachuau J, Shepherd A, Dey D, Martin-Caraballo M. CNTF-evoked activation of JAK and ERK mediates the functional expression of T-type Ca2+ channels in chicken nodose neurons. J Neurochem. 2009;108:246–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wierenga AT, Vogelzang I, Eggen BJ, Vellenga E. Erythropoietin-induced serine 727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in erythroid cells is mediated by a MEK-, ERK-, and MSK1-dependent pathway. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:398–405. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen-Jackson H, Panopoulos AD, Zhang H, Li HS, Watowich SS. STAT3 controls the neutrophil migratory response to CXCR2 ligands by direct activation of G-CSF-induced CXCR2 expression and via modulation of CXCR2 signal transduction. Blood. 2010;115:3354–63. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saxena NK, Sharma D, Ding X, Lin S, Marra F, Merlin D, et al. Concomitant activation of the JAK/STAT, PI3K/AKT, and ERK signaling is involved in leptin-mediated promotion of invasion and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2497–507. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Inhibition of GSK-3beta as a target for cardioprotection: the importance of timing, location, duration and degree of inhibition. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2005;9:447–56. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Juhaszova M, Zorov DB, Kim SH, Pepe S, Fu Q, Fishbein KW, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta mediates convergence of protection signaling to inhibit the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1535–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI19906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Juhaszova M, Zorov DB, Yaniv Y, Nuss HB, Wang S, Sollott SJ. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cardioprotection. Circ Res. 2009;104:1240–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali A, Hoeflich KP, Woodgett JR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: properties, functions, and regulation. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2527–40. doi: 10.1021/cr000110o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hetman M, Hsuan SL, Habas A, Higgins MJ, Xia Z. ERK1/2 antagonizes glycogen synthase kinase-3beta-induced apoptosis in cortical neurons. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49577–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maurer U, Charvet C, Wagman AS, Dejardin E, Green DR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis by destabilization of MCL-1. Mol Cell. 2006;21:749–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hardt SE, Sadoshima J. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta: a novel regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and development. Circ Res. 2002;90:1055–63. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018952.70505.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rottlaender D, Boengler K, Wolny M, Schwaiger A, Motloch LJ, Ovize M, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta transfers cytoprotective signaling through connexin 43 onto mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107479109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Vigneron F, Dos SP, Lemoine S, Bonnet M, Tariosse L, Couffinhal T, et al. GSK-3beta at the crossroads in the signalling of heart preconditioning: implication of mTOR and Wnt pathways. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;90:49–56. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naoum JJ, Zhang S, Woodside KJ, Song W, Guo Q, Belalcazar LM, et al. Aortic eNOS expression and phosphorylation in Apo-E knockout mice: differing effects of rapamycin and simvastatin. Surgery. 2004;136:323–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McCormick ME, Goel R, Fulton D, Oess S, Newman D, Tzima E. Platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 regulates endothelial NO synthase activity and localization through signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-dependent NOSTRIN expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:643–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zimmermann K, Opitz N, Dedio J, Renne C, Muller-Esterl W, Oess S. NOSTRIN: a protein modulating nitric oxide release and subcellular distribution of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17167–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252345399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haghikia A, Missol-Kolka E, Tsikas D, Venturini L, Brundiers S, Castoldi M, et al. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3-mediated regulation of miR-199a-5p links cardiomyocyte and endothelial cell function in the heart: a key role for ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1287–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bolli R. The late phase of preconditioning. Circ Res. 2000;87:972–83. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xi L, Jarrett NC, Hess ML, Kukreja RC. Essential role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in monophosphoryl lipid A-induced late cardioprotection: evidence from pharmacological inhibition and gene knockout mice. Circulation. 1999;99:2157–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xuan YT, Guo Y, Zhu Y, Wang OL, Rokosh G, Bolli R. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase plays an obligatory role in the late phase of ischemic preconditioning by activating the protein kinase C epsilon p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase pSer-signal transducers and activators of transcription1/3 pathway. Circulation. 2007;116:535–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.689471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.