Abstract

Peptide YY (PYY) and ghrelin (GHR) may modulate one another’s actions within the hypothalamus. Peripheral infusion of PYY in humans acutely suppresses circulating concentrations of GHR. Whether an association between PYY and GHR exists in the peripheral circulation of humans over 24h is unknown. The purpose of this study was to determine if circulating concentrations of PYY and GHR were significantly associated over 24h in humans. Participants (n=13) were normal weight, moderately active, women ages 18 – 24 y. Blood samples were obtained q10 min for 24h and assayed using RIA for total PYY and total GHR hourly from 0800–1000h and 2000–0800h and q20 min from 1000–2000h. Dietary intake during the 24h procedure was comprised of 55% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 15% protein (three meals and a snack). Statistical analyses included linear mixed-effects modeling to test whether PYY predicted GHR concentrations over 24h. Participants weighed 57.0±1.5kg and had 26.1±1.5% body fat (15.0±1.1kg), 42.1±1.1kg fat free mass, a BMI of 21.3±0.5kg/m2 and RMR of 1072±28kcal/24h. Visually, PYY and GHR exhibited an inverse association over nearly the entire 24h period. Statistically, circulating concentrations of 24h PYY predicted 24h GHR (ghrelin = 1860.51 – 2.14*PYY; p = 0.04). Circulating concentrations of PYY are inversely associated with GHR over 24h. These data provide evidence that PYY may contribute to the modulation of the secretion of GHR in normal weight, premenopausal women over a 24h period and supports similar inferences from experimental studies in animals and humans.

Keywords: ghrelin, peptide YY

1. INTRODUCTION

Studies using animal models [2] and humans [5, 7] support the roles of ghrelin and peptide YY (PYY) in the modulation of energy intake. Whereas PYY is one of several satiety hormones, ghrelin is the only hunger hormone that has been identified to date. It has been proposed that ghrelin and PYY oppose the actions of one another at the hypothalamus [11]. However, these hormones are secreted from cells along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract in the periphery and secretion is modulated by caloric as well as macronutrient content of meals [5, 7]. PYY may be involved in slowing GI motility and suppressing gastric acid secretion [10] whereas ghrelin stimulates those same actions [8]. One study infused ghrelin and demonstrated an attenuation of the effects of PYY on gastric acid secretion and motility [4]. Thus, ghrelin and PYY may oppose the actions of one another on digestion and absorption within the GI tract.

Although ghrelin and PYY may reciprocally inhibit the actions of one another on the GI tract, the mechanism through which ghrelin and PYY may modulate the actual secretory profiles of one another in the periphery is unknown [3]. Ghrelin decreases, whereas PYY increases postprandially and thus, the reciprocal association may exclusively be a result of the incidental regulation by way of nutrient ingestion. However, evidence to support a regulatory association between ghrelin and PYY was demonstrated when infusion of PYY in the fasted state of obese and lean individuals suppressed pre- and postprandial circulating concentrations of ghrelin [1]. In light of this, it is attractive to hypothesize that ghrelin and PYY may be directly involved in modulating the secretion of one another in a negative feedback manner in the periphery. However, no study has examined whether an inverse association between ghrelin and PYY exists in the peripheral circulation of healthy, normal weight humans over an entire 24h period. To that end, the current study sought to determine if the proposed opposing actions of ghrelin and PYY at the hypothalamus could be related to their patterns in the peripheral circulation. We hypothesized that circulating concentrations of total PYY would be inversely associated with circulating concentrations of total ghrelin over 24h in normal weight, premenopausal women.

2. PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

2.1. Experimental Design and Participants

We examined the 24h profiles of total PYY and total ghrelin in 13 women ages 18–24y. Non-smoking, non-exercising (<1h/wk exercise) women with a body weight (BW) of 48–73kg, 15–30% body fat and BMI between 18–25kg/m2 were included. Exclusion criteria included evidence of disordered eating or history of an eating disorder, loss/gain of BW (±2.3kg) in the past year, or use of hormonal contraceptives or medications that may alter metabolism. Participants completed an informed consent that was approved by the Biomedical Institutional Review Board of The Pennsylvania State University.

2.2. Determination of Weight Maintenance Energy Requirements

Participants were prescribed caloric intake to maintain BW estimated based 24h energy expenditure (EE). This was determined from the sum of 24h resting metabolic rate (RMR; kcal/24h) and EE above rest determined with the use of a research accelerometer (AM) worn over 7 days that measured the energy cost of all non-purposeful activity (triaxial RT3 accelerometer, Stayhealthy, Monrovia, CA). BW was recorded to the nearest 0.01kg. RMR using indirect calorimetry and hydrostatic weighing to obtain body composition were performed using previously published methods [5]. Participants were deemed weight stable if BW, obtained once daily in the morning, fluctuated by ±1kg over a period of 7 days.

2.3. 24-hour Repeated Blood Sampling Protocol

Participants arrived fasted (8–12h) and abstinent from exercise or caffeine ingestion (24h) at the general clinical research center (GCRC) at 0730h the day of testing. After insertion of an IV catheter into a forearm vein, blood samples were obtained q 10 min for 24h (total=488mL) while participants remained supine. Samples were allowed to clot at room temperature and spun in a centrifuge for 15min at 2500 rpm. Serum samples were untreated, aliquoted to serum storage tubes and stored at −80°C until analysis.

Dietary intake (total=1452±48kcal) was comprised of 55% carbohydrates, 30% fat, and 15% protein and consisted of 3 meals and a snack prepared for 0900h (412±28kcal), 1200h (472±24kcal), 1800h (504±0kcal) and 2100h (66±4kcal). Energy provided to participants was 85% of their prescribed weight maintenance energy needs to account for reductions in EE due to inactivity associated with bed rest. Participants consumed all food provided within 30 minutes at each meal.

2.4. Radioimmunoassay Analysis

Serum samples were assayed for total ghrelin using the Linco Research RIA kit (St. Charles, MO). Assay sensitivity was 100pg/mL. The intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation for the high and low controls were 2.7% and 16.7% and 1.2% and 14.7%, respectively. Total PYY was assayed using an RIA (Millipore, Billerica, MA). PYY assay sensitivity was 10pg/mL and the intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 2.9% and 7.1%, respectively. Samples were assayed hourly from 0800–1000h and from 2000–0800h and every 20 minutes from 1000–2000h.

2.5. Data and Statistical Analysis

Fasting PYY and fasting ghrelin were designated as the concentrations at 0800h. Peaks were defined as the highest concentration measured 1–2h before (ghrelin) or after (PYY) meal administration. Twenty-four h mean represented the average of all concentrations measured over 24h. Total area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal rule.

Linear mixed-effects (random coefficients) models were fitted to participants’ responses to determine if PYY concentrations were associated with ghrelin concentrations over 24h. A regression coefficient was considered significantly different from 0 if the p-value of the corresponding (t | z) test was ≤0.05. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. All analyses were performed using SPSS software (Version 18.0; Chicago, IL).

3. RESULTS

Participants were non-exercising, normal weight (57.0 ± 1.5kg) premenopausal women between the ages of 18 and 24 yr. Participants had 26.1 ± 1.5% body fat (15.0 ± 1.1kg), 42.1 ± 1.1kg fat free mass and a BMI of 21.3 ± 0.5kg/m2. Average VO2max was 37.8 ± 1.4ml/kg/min. This value is between the 50th and 55th percentile for women ages 20–29 (ACSM Guidelines 8th Ed.) and likely consistent with a moderately active lifestyle. Average RMR was 1072 ± 28kcal/24h and EE from AM was 658 ± 54kcal.

Characteristics of ghrelin and PYY are presented in Table 1. Fasting ghrelin (1863 ± 132pg/ml) and fasting PYY (68.7 ± 7.1pg/ml), preprandial (ghrelin) and postprandial (PYY) meal peaks and two indices of the 24h profiles of ghrelin and PYY, AUC and 24h mean, are presented for all participants.

Table 1.

Descriptive Variables Characterizing Ghrelin and PYY

| Variable | Ghrelin Mean ± SEM |

PYY Mean ± SEM |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting (pg/ml) | 1862 ± 132 | 68.7 ± 7.1 |

| Total AUC (pg/mlx24h) | 37658 ± 1857 | 1932.8 ± 163.4 |

| 24h Mean (pg/ml) | 1627 ± 79 | 85.3 ± 7.2 |

| Breakfast Peak (pg/ml) | 1862 ± 132 | 98.8 ± 9.9 |

| Lunch Peak (pg/ml) | 1701 ± 95 | 113.3 ± 10.0 |

| Dinner Peak (pg/ml) | 1960 ± 92 | 100.5 ± 8.4 |

| Nocturnal Peak (pg/ml) | 1906 ± 78 | ------- |

| Breakfast Nadir (pg/ml) | 1418 ± 88 | 81.4 ± 8.9 |

| Lunch Nadir (pg/ml) | 1346 ± 75 | 77.2 ± 6.3 |

| Dinner Nadir (pg/ml) | 1448 ± 88 | 77.7 ± 8.1 |

| Nocturnal Nadir (pg/ml) | ------- | 63.4 ± 5.9 |

| Time of Breakfast Peak (h) | 08:40 ± 0:10 | 10:40 ± 0:08 |

| Time of Lunch Peak (h) | 12:00 ± 0:05 | 13:40 ± 0:22 |

| Time of Dinner Peak (h) | 18:00 ± 0:03 | 18:40 ± 0:04 |

| Time of Nocturnal Peak (h) | 01:00 ± 0:12 | ------- |

| Time of Breakfast Nadir (h) | 10:40 ± 0:09 | 11:40 ± 0:07 |

| Time of Lunch Nadir (h) | 14:00 ± 0:14 | 16:40 ± 0:19 |

| Time of Dinner Nadir (h) | 19:40 ± 0:12 | 20:00 ± 0:11 |

| Time of Nocturnal Nadir (h) | ------- | 06:00 ± 01:30 |

Note: Ghrelin meal peaks are preprandial and ghrelin meal nadirs are postprandial. PYY meal nadirs are preprandial and PYY meal peaks are postprandial.

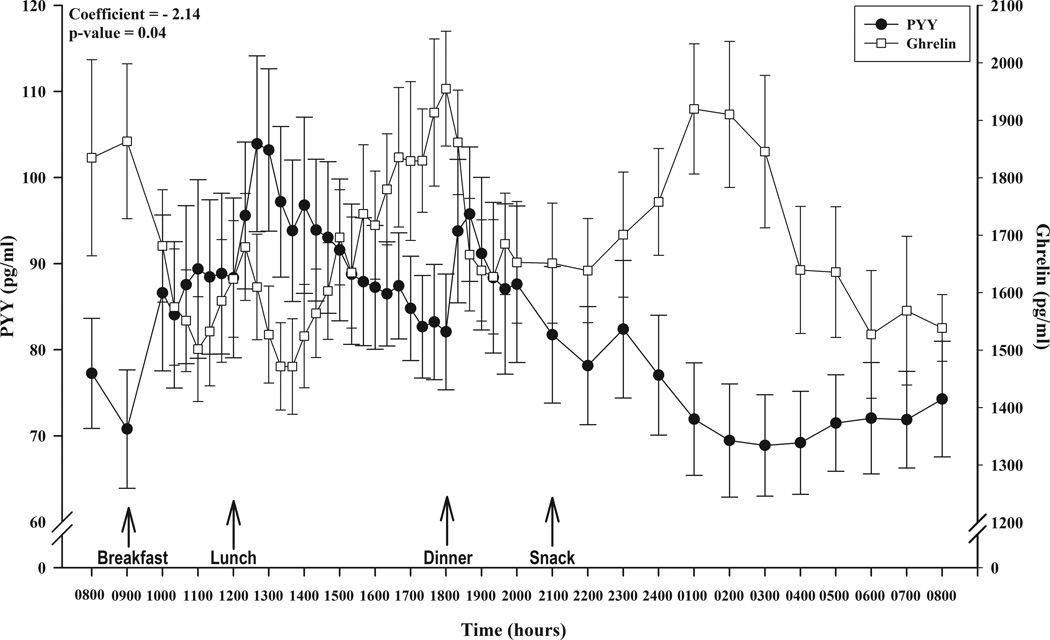

Figure 1 depicts the 24h circulating profiles of total ghrelin and total PYY. Analysis of the data with linear mixed-effects model indicated that circulating total PYY was a statistically significant predictor of total ghrelin during the 24h period (ghrelin = 1860.51–2.14*PYY; p = 0.04) such that increases in circulating concentrations of PYY were associated with decreases in circulating concentrations of ghrelin.

Figure 1.

Composite profile of circulating concentrations of (●) total PYY (pg/ml) and (□) total ghrelin (pg/ml) over 24 hours illustrating meal administration time points and results of the linear mixed modeling analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM; p<0.05.

4. Discussion

We have previously demonstrated that the diurnal rhythms of ghrelin [7] and PYY [5] are driven by food-related events such as meal energy content and meal timing. These peptides are thus intimately involved in the modulation of energy intake and may play a role in both acute [5, 7] and chronic [6] energy balance. Non-food-related events such as the nocturnal rise in ghrelin, typically observed between 0100–0400h [7], also occur. Thus, it is important to characterize the 24h patterns of these hormones in the same study and test their relation to each other. To that end, our results support a role for PYY in the modulation of ghrelin in that circulating concentrations of total PYY were inversely associated with circulating concentrations of total ghrelin over an entire 24h period. This statistical finding is obvious upon visual inspection. For example, PYY concentrations were highest subsequent to the lunch meal after which ghrelin concentrations were lowest. Additionally, the nocturnal peak in ghrelin occurred at 0100h after a long rise, and this rise and peak are coincident with a prolonged decline in PYY. This inverse relation between PYY and ghrelin might reflect a reduced inhibition of ghrelin as PYY declines.

Previous studies have proposed that the underlying mechanism by which ghrelin and PYY modulate energy balance operates at the level of the hypothalamus where these hormones cross the blood-brain barrier [9] and bind to receptors in the arcuate nucleus [11]. Few studies have examined the association between ghrelin and PYY in the peripheral circulation [1, 4]. One study demonstrated that fasting concentrations as well as the pre-prandial rise in ghrelin were suppressed 2h subsequent to PYY infusion in obese and lean individuals [1]. To date no study has demonstrated an association between these two gut peptides in the peripheral circulation of humans over an entire 24h period in moderately active, normal weight, premenopausal women. Notably, the participants in our study were weight stable for at least six months prior to their entry into the study. During abnormal energy balance conditions, such as obesity or periods of weight loss, PYY and ghrelin may not be associated in the circulation in the same way and thus more research is needed to determine if an “uncoupling” occurs between ghrelin and PYY with changes in BW. The present study may be a valuable reference to which results from studies involving abnormal states of energy balance can be compared.

It is important to note that factors other than PYY may also be modulating ghrelin. This is supported during times when no apparent inverse relation between PYY and ghrelin is evident. For example, ghrelin concentrations continue to rise to peak concentrations just subsequent to lunch when PYY concentrations remain stable within the hour prior and are beginning to increase. As well, ghrelin begins to decline subsequent to its nocturnal peak when PYY continues to decrease to its nadir at 0400h. Currently, it is unclear what factors modulate ghrelin secretion during times other than meal-related events such as the nocturnal rise. One study demonstrated that sleep may inhibit ghrelin [13] and other studies have associated sleep deprivation with elevated ghrelin [14]; however, the mechanism through which this occurs is unknown. The increase in ghrelin that leads to the nocturnal peak has been interpreted as a post dinner rebound that is then impacted by the onset of sleep which causes the gradual decline in ghrelin observed subsequent to the nocturnal peak [13]. It is also attractive to hypothesize that other factors, the secretion of which ghrelin is known to stimulate such as growth hormone or cortisol [16], may be involved in the feedback inhibition of ghrelin, particularly during sleeping hours when the modulation of ghrelin by food intake is not a contributing factor.

A limitation of this study is that we measured total PYY and ghrelin and not the more biologically active forms i.e., PYY3–36 and acylated ghrelin. However, it may be advantageous to capture both forms as studies have demonstrated that PYY1–36 as well as PYY3–36 inhibit energy intake and suppress subjective hunger ratings [12] where as acylated ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin both stimulate energy intake [15].

In conclusion, circulating concentrations of PYY were inversely associated with circulating concentrations of ghrelin over 24h in normal weight, premenopausal women during a period of weight stability. These data provide corroborative evidence of a reciprocal association between PYY and ghrelin over a 24h period in women. These findings may substantiate inferences from experimental studies in humans and animals suggesting that changes in PYY may be modulating the secretion of ghrelin.

-

-

Circulating PYY was a significant predictor of ghrelin over 24 hours in humans

-

-

Increases in circulating PYY were associated with decreases in circulating ghrelin

-

-

PYY may be modulating ghrelin secretion in normal weight women over a 24 hour period

-

-

Findings substantiate experimental inferences that PYY modulates ghrelin secretion

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grants 1R01HD39245-01A1 (N. Williams), M01 RR 10732 and US DoD PR054531 (N.I. Williams and M.J. De Souza). We thank the staff that spent numerous hours on the study and the cooperation of the study volunteers. Brenna R. Hill is supported by the Intercollegiate Graduate Degree Program in Physiology, at the Pennsylvania State University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors have nothing to disclose. All authors have approved the final submitted manuscript.

References

- 1.Batterham RL, Cohen MA, Ellis SM, Le Roux CW, Withers DJ, Frost GS, et al. Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3-36. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:941–948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, Herzog H, Cohen MA, Dakin CL, et al. Gut hormone PYY(3-36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature. 2002;418:650–654. doi: 10.1038/nature00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camina JP, Carreira MC, Micic D, Pombo M, Kelestimur F, Dieguez C, et al. Regulation of ghrelin secretion and action. Endocrine. 2003;22:5–12. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:22:1:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chelikani PK, Haver AC, Reidelberger RD. Ghrelin attenuates the inhibitory effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 and peptide YY(3-36) on food intake and gastric emptying in rats. Diabetes. 2006;55:3038–3046. doi: 10.2337/db06-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill BR, De Souza MJ, Williams NI. Characterization of the diurnal rhythm of peptide YY and its association with energy balance parameters in normal-weight premenopausal women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E409–E415. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00171.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leidy HJ, Gardner JK, Frye BR, Snook ML, Schuchert MK, Richard EL, et al. Circulating ghrelin is sensitive to changes in body weight during a diet and exercise program in normal-weight young women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:2659–2664. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leidy HJ, Williams NI. Meal energy content is related to features of meal-related ghrelin profiles across a typical day of eating in non-obese premenopausal women. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38:317–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda Y, Tanaka T, Inomata N, Ohnuma N, Tanaka S, Itoh Z, et al. Ghrelin stimulates gastric acid secretion and motility in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:905–908. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonaka N, Shioda S, Niehoff ML, Banks WA. Characterization of blood-brain barrier permeability to PYY3-36 in the mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:948–953. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pappas TN, Debas HT, Goto Y, Taylor IL. Peptide YY inhibits meal-stimulated pancreatic and gastric secretion. Am J Physiol. 1985;248:G118–G123. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.248.1.G118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riediger T, Bothe C, Becskei C, Lutz TA. Peptide YY directly inhibits ghrelin-activated neurons of the arcuate nucleus and reverses fasting-induced c-Fos expression. Neuroendocrinology. 2004;79:317–326. doi: 10.1159/000079842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloth B, Holst JJ, Flint A, Gregersen NT, Astrup A. Effects of PYY1-36 and PYY3-36 on appetite, energy intake, energy expenditure, glucose and fat metabolism in obese and lean subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1062–E1068. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00450.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R, Scherberg N, Van Cauter E. Twenty-four-hour profiles of acylated and total ghrelin: relationship with glucose levels and impact of time of day and sleep. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:486–493. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:846–850. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toshinai K, Yamaguchi H, Sun Y, Smith RG, Yamanaka A, Sakurai T, et al. Des-acyl ghrelin induces food intake by a mechanism independent of the growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2306–2314. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weikel JC, Wichniak A, Ising M, Brunner H, Friess E, Held K, et al. Ghrelin promotes slow-wave sleep in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E407–E415. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00184.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]