Abstract

Aims

To report the surgical outcome of tectonic graft using glycerol-preserved donor corneas to treat perforated keratitis.

Methods

The medical records were reviewed of all patients treated for perforated keratitis using glycerol-preserved corneas at a single institution between 1 July 2004 and 31 June 2010. The clinical features, precipitating factors, adjuvant therapies, and therapeutic outcomes were analyzed. Success was defined as re-epithelialization of the ocular surface without evisceration.

Results

Fourteen eyes from 14 patients (6 male and 8 female) were included. Age ranged from 58 to 84 years (average, 70.71±8.52 years) and the follow-up time ranged from 7 to 56 months (mean, 25.35±16.84 months). The culture results showed five bacterial infections, five cases of fungal keratitis, and one mixed infection; the culture results were negative for three patients. Satisfactory anatomical integrity was obtained in eight grafts (57.14%) that healed with neovascularization. Six grafts (48.85%) showed delayed re-epithelialization and were repaired with conjunctival flaps to maintain ocular surface integrity. Three patients developed secondary glaucoma and received trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation. Thirteen patients had satisfactory anatomical integrity without evisceration or exenteration, while one patient received evisceration at 39-month follow-up because of intractable glaucoma.

Conclusions

Glycerol-preserved donor corneas combined with anterior vitrectomy with or without conjunctival flaps may be effective substitutes for evisceration surgery in patients with perforated keratitis.

Keywords: corneal graft, glycerol-preserved cornea, keratitis, keratoplasty

Introduction

The use of glycerol-preserved corneas for patch grafts has allowed eye banks to utilize nonviable tissue for emergency surgery1, 2, 3, 4 in situations in which fresh donor corneas are not available. Although the use of keratoplasty to treat pathological corneas has been replaced almost entirely by penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) using viable donor corneas,5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 the supply of high-quality corneas is limited in many countries due to unreliable transportation, inconsistent distribution, and limited tissue shelf life. Glycerol preservation is a simple, effective technique that facilitates long-term storage of acellular corneal tissue for up to 5 years.

The objective of this article is to determine the outcomes after use of glycerol-preserved corneas in tectonic grafts in cases of perforated keratitis with little visual potential. Tectonic corneal patch graft combined with anterior vitrectomy with or without conjunctival flap may be a viable method to preserve the contour of the eyeball preceding evisceration of the infected eye.

Materials and methods

The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (IRB: 97-0573B). The medical records of patients who received glycerol-preserved corneal patch grafts performed at the hospital from July 2004 through June 2010 were reviewed retrospectively.

Fourteen patients with perforated keratitis underwent tectonic patch grafts. Routine diagnostic smears and cultures were performed. The demographic data gathered upon initial presentation included gender, age, precipitating factors, systemic disease, and keratitis severity. Other information gathered included previous medication(s), treatment methods, re-epithelialization time, complications, and length of follow-up. Sequential photographic documentation of the keratitis was obtained from each patient. Each eye received topical antibiotics consisting of Vancomycin, Cefazolin, Amikacin, Natamycin 5% (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA), or Amphotericin B (1.5–5%) as an initial treatment (Table 1), according to clinical conditions.

Table 1. Summary of clinical information.

| Case No/age/sex/eye | Pre-existing disease or risk factor/culture | 1st OP | Size of graft (mm)/adjuvant therapy | Re-epithelialization (days) | VA initial/final | Complication | F/U months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/74/F/OD | PBK/Mycobacteria abscessus | No | 8 × 8/Conjunctival flap | No | HM/NLP | Delayed re-epithelialization | 27 |

| 2/84/M/OS | PBK, NVG/Pseuodmonas aeruginosa | AMT | 7.5 × 7.5 | 14 | HM/NLP | No | 15 |

| 3/60/F/OD | Farmer/Fusarium solani | AMT | 7 × 7 | 12 | HM/HM | No | 34 |

| 4/67/M/OD | Pseudophakia, pterygium op/culture negative | No | 7.5 × 7.5 | 14 | LP/NLP | No | 60 |

| 5/83/M/OD | PBK/culture negative | No | 7.5 × 7.5/Conjunctival flap | No | NLP/NLP | Delayed re-epithelialization | 7 |

| 6/58/M/OS | PBK, trichiasis/Fusarium spp | No | 7.5 × 7.5 | 10 | HM/NLP | N | 56 |

| 7/81/M/OD | Pseudophakia, leucoma/Streptococcus pneumoniae | AMT | 7 × 7/Conjunctival flap | No | LP/NLP | Delayed re-epithelialization | 9 |

| 8/72/F/OD | Leucoma adherence/culture negative | No | 6 × 6/TSCP | 19 | HM/CF | Glaucoma | 18 |

| 9/58/F/OD | PACG, trabeculectomy/Pseudomonas aeruginosa | AMT | 7 × 7 | 12 | LP/HM | N | 17 |

| 10/68/F/OS | PDR, NVG, PBK/acremonium | No | 6.0 × 6.0/TSCP | 9 | LP/NLP | Glaucoma | 14 |

| 11/68/F/OD | PBK/yeast, Acinetobacter baumannii | Glue/TSCL | 7 × 7/Conjunctival flap | No | LP/LP | Delayed re-epithelialization | 13 |

| 12/76/F/OD | DM, PBK/Pseudomonas aeruginosa | No | 6 × 6/Conjunctival flap | No | HM/LP | Delayed re-epithelialization | 10 |

| 13/72/F/OS | PBK, DM/Fusarium keratitis | AMT ICA | 7 × 7/TSCP Conjunctival flap | No | LP/NLP | Glaucoma Delayed re-epithelialization Evisceration | 45 |

| 14/M/69/OS | Farmer/Fusarium keratitis | AMT ICA | 7.5 × 7.5 | 16 | LP/NLP | Glaucoma | 36 |

Abbreviations: AMT, amniotic membrane transplantation; CF, counting finger; HM, hand motion; ICA, intracameral amphotericin injection; LP, light perception; NV, neovascularization; NLP, no light perception; NVG, neovascular glaucoma; PBK, pseudophakic bullous keratopathy; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PAS, peripheral anterior synechiae; TSCP, trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation; VA, visual acuity.

The donor corneas were obtained from corneas not suitable for optical PKP and were preserved in a glycerol environment at 4 °C.

We began the procedure by excising the ulcerated areas from the corneas. We then removed the necrotic tissue and intraocular lens, performed anterior vitrectomy and made an intravitreous injection of antibiotics. Then, we trimmed the glycerol-preserved cornea to an appropriate size (range, 5–8 mm) according to the size of the corneal infiltration (Table 1), and sutured it onto the corneal base with 10-0 nylon-interrupted sutures. After the surgery, the dose of antibiotics was tapered gradually over 2 weeks, while observing the patient for signs of infection.

Results

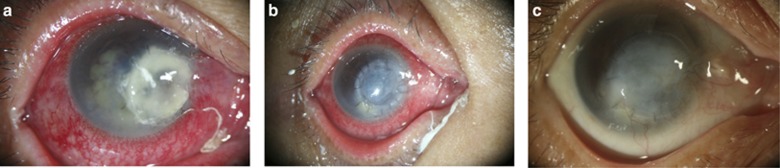

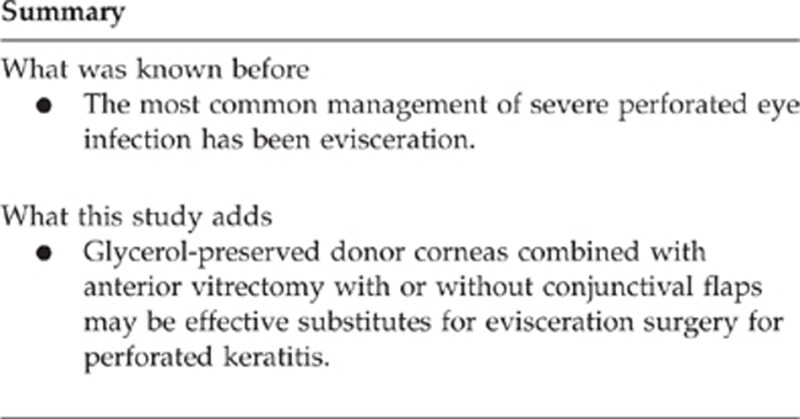

Fourteen eyes from 14 patients (6 male and 8 female) were included. Their ages ranged from 58 to 84 years (average, 70.71±8.52 years). The demographics and clinical findings are listed in Table 1. In this group, mean follow-up time was 25.35±16.84 months (range, 7–56 months). The culture results from corneal scrapings revealed bacterial infection in five eyes, including Mycobacterium abscessus (Patient 1), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Patients 2, 9, and 12) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Patient 7). Five patients had fungal keratitis, including Fusarium solani isolated from Patients 3 (Figure 1), 6, 13, and 14 as well as Acremonium spp keratitis in Patient 10 (Figure 2). One patient suffered combined yeast and Acinetobactor baumaunnii (Patient 11) infection. Cultures were negative in three other patients, probably due to previous topical antibiotic usage.

Figure 1.

Fusarium keratitis with imminent perforation despite previous amniotic membrane transplantation. (a) Anterior chamber exudation is evident. (b) Ocular surface integrity maintained at day 12 after glycerol-preserved cornea patch graft. (c) At eight months follow-up, the cornea healed, showing opacity and neovascularization.

Figure 2.

Acremonium keratitis perforation with iris protrusion. (a) Iris protrusion evident. (b) Patch graft re-epithelialized at 2 weeks postoperative follow-up. High intraocular pressure was managed with trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation. (c) Graft neovascularization was evident at three months postoperative follow-up.

Postoperative bullous keratoplasty (pseudophakia/aphakia and glaucoma) were the major risk factors for the occurrence of keratitis in nine patients (64.3% Patients 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13). Patients 3, 13, and 14 (21.4%) were field workers with Fusarium keratitis. Six patients (Patients 2, 3, 7, 9, 13, and 14) received amniotic membrane grafts, and one patient (Patient 11) had received cyanoacrylate glue for corneal perforation before patch graft. Postoperatively, three patients (Patients 8, 10, and 13) had secondary glaucoma and received trans-scleral cyclophotocoagulation (TSCP) to relieve pain. Glycerol-preserved cornea grafts ranging from 6 × 6 mm to 8 × 8 mm in diameter. Pre-tectonic patch graft visual acuity ranged from no light perception to hand motion. Delayed re-epithelialization occurred in most grafts, and six grafts (48.85%, Patients 1, 5, 7, 11, 12, and 13) were repaired with conjunctival flaps to maintain ocular surface integrity. Other grafts (8/14, 57.14%) healed with neovascularization. One patient (Patient 13) suffered from secondary angle-closure glaucoma postoperatively that was refractory to TSCP and received evisceration at 39-month follow-up.

Conclusion

The source for fresh donor corneas in Southeast Asia is limited and mostly reserved for cases of optical PKP. The alternative method is to use the corneal buttons not suitable for PKP, preserving them in a 4 °C glycerol environment, and saving them for emergency therapeutic keratoplasty. Glycerol is a dehydrating agent with antimicrobial and antiprotease properties. However, glycerol will not preserve endothelial viability, a condition needed for optical PKP; cryopreservation12, 13 and 34 °C organ culture14 will allow long-term storage of viable corneal tissue. Cryopreservation and organ culture, because of their technical complexity and cost, have limited application in the areas, which lack fresh donor corneas.

In cases of recalcitrant keratitis with perforation which have been scheduled for evisceration, an alternative procedure to evisceration or enucleation may be resection of the necrotic cornea with removal of the anterior chamber exudation and intraocular lens. After this, an anterior vitrectomy may be combined with an antibiotic injection into the vitreous. Finally, a patch graft may be used to restore surface integrity.

Using glycerol-preserved cornea has several potential benefits. First, it is readily available for emergency conditions and costs less than fresh cadaver corneas. Second, the use of devitalized tissue reduces the risk of potential graft rejection, especially for patients with poor follow-up care or compliance with long-term immunosuppressive medications. Third, it is stored in highly concentrated glycerol, reducing the possibility of microbial contamination. The incidence of postkeratoplasty ocular infection of recipients related to donor contamination is very rare. However, it remains a major concern in corneal transplantation.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

In the current study, postoperative bullous keratoplasty (9/14, 64.3%) was the major risk factor for keratitis due to ocular surface diseases with recurrent erosion of the epithelium.21, 22 Fusarium infection is the most common pathogen leading to cornea perforation (28.8%), followed by P. aeruginosa keratitis (21.4%). This is consistent with the literature that Pseudomonas and Fusarium keratitis are the most virulent and rapid progressive pathogens. Moreover, Pseudomonas keratitis/scleritis infections account for 44.4% of endophthalmitis cases at our institute.23, 24, 25, 26, 27

Our patients had very good postoperative courses (Table 1). With a mean follow-up time of 25.35 months (range, 7–56 months), infections were eradicated without recurrence in all eyes, satisfactory anatomical integrity was obtained in eight grafts (57.14%) that healed with neovascularization; six grafts (48.85%) with delayed re-epithelialization and graft melting were repaired with conjunctival flaps to maintain ocular surface integrity. According to the literature, older age, past ocular surgery, severe keratitis, and poor visual acuity at presentation account for the poor prognosis of keratitis.28, 29 In our study, 57.1% of patients (Patients 1, 2, 5, 6, 10, 11, and 13) had a chronic debilitating medical condition (such as stroke) that precluded the early intervention of keratitis, medication compliance or regular follow-up care. All patients in this study had previous ocular surgery that left the eyes pseudophakic or aphakic, thus facilitating the progression of infection to the posterior segments.

The common complications of PKP (especially in patients with infective keratitis) are rejection, infection recurrence, and glaucoma. No graft rejection was noted during follow-up in our study, because the glycerol-preserved corneas contained no viable cells. A 24–27% recurrence and rejection rate has been reported for the 5-year follow-up to post therapeutic keratoplasty using fresh donor corneas.30, 31, 32 Owing to the low or negative rejection rate, we plan to reduce the postoperative use of corticosteroids, in hopes of decreasing the chance of recurring infection while using glycerol-preserved corneas.

Moreover, three (21.4%) patients received TSCP for postoperative high intraocular pressure. Disruption of the anterior chamber structure due to infection, preoperative glaucoma, and aphakia/pseudophakia are risk factors for secondary glaucoma. The reported incidence of secondary glaucoma after PKP ranges 10–53%.33, 34, 35, 36, 37 One subject (7.1%, Patient 13) suffered from secondary glaucoma with painful red eye and no light perception and received evisceration at 39 month follow-up.

Compared with fresh donor corneas, glycerol-preserved corneas remained opaque after re-epithelialization and offered a less satisfactory cosmetic effect. Infection eradication without recurrence was obtained all eyes with the excision of the corneal infiltration; anterior vitrectomy; intravitreous injection of Ceftazidime, Amikin and Amphotericin B; and postkeratoplasty topical antibiotic usage. At the end of follow-up, satisfactory anatomical integrity was obtained in 13 (92.8%) patients; 1 patient (Patient 13) received evisceration due to intractable glaucoma with painful blindness.

In summary, glycerol-preserved cornea patch graft with or without a conjunctival advancement flap may be an option to avoid evisceration or enucleation in specific cases, but special care must be taken to eradicate infection.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- King JH, Townsend WM. The prolonged storage of donor corneas by glycerine dehydration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1984;82:106–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JH, McTigue JW, Meryman HT. Preservation of corneas for lamellar keratoplasty: a simple method of chemical glycerine-dehydration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1961;59:194–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JH. The use of preserved ocular tissues for transplantation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1958;56:203–211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JH. Keratoplasty: experimental studies with corneas preserved by dehydration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1956;54:567–609. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WL, Wu CY, Hu FR, Wang IJ. Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty for microbial keratitis in Taiwan from 1987 to 2001. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sony P, Sharma N, Vajpayee RB, Ray M. Therapeutic keratoplasty for infectious keratitis: a review of the literature. CLAO J. 2002;28:111–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JC. Use of penetrating keratoplasty in acute bacterial keratitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:502–506. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.7.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anshu A, Parthasarathy A, Mehta JS, Htoon HM, Tan DT. Outcomes of therapeutic deep lamellar keratoplasty and penetrating keratoplasty for advanced infectious keratitis: a comparative study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Sachdev R, Jhanji V, Titiyal JS, Vajpayee RB. Therapeutic keratoplasty for microbial keratitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:293–300. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833a8e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobe JR, Moura BT, Robin JB, Smith RE. Results of penetrating keratoplasty for the treatment of corneal perforations. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:939–941. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070090041035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Dong X, Shi W. Treatment of fungal keratitis by penetrating keratoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1070–1074. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.9.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao YF, Zhang YM, Zhou P, Zhang B, Qiu WY, Tseng SC. Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty in severe fungal keratitis using cryopreserved donor corneas. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:543–547. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.5.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W, Liu M, Gao H, Li S, Wang T, Xie L. Penetrating keratoplasty with small-diameter and glycerin-cryopreserved grafts for eccentric corneal perforations. Cornea. 2009;28:631–637. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318191b857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pels L. Organ culture: the method of choice for preservation of human donor corneas. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:523–525. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.7.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehany U, Balut G, Lefler E, Rumelt S. The prevalence and risk factors for donor corneal button contamination and its association with ocular infection after transplantation. Cornea. 2004;23:649–654. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000139633.50035.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyhani K, Seedor JA, Shah MK, Terraciano AJ, Ritterband DC. The incidence of fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis following penetrating keratoplasty. Cornea. 2005;24:288–291. doi: 10.1097/01.ico..0000138832.3486.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotveld JH, Raijmakers AJ, Henry Y, Zaal MJ. Donor-to-host transmitted Candida endophthalmitis after penetrating keratoplasty. Cornea. 2005;24:887–889. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000157403.27150.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan SS, Wilhelmus KR. Quality assessment and microbiologic screening of donor corneas. Cornea. 2007;26:953–955. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31811dfb72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermel M, Salla S, Hamsley N, Steinfeld A, Walter P. Detection of contamination during organ culture of the human cornea. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:117–126. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish KS, Ramamurthi S, Butcher I, Ramaesh K. Is microbiological analysis of donor cornea transport culture media necessary. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:137–138. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Apel A, Stapleton F. Risk factors and causative organisms in microbial keratitis. Cornea. 2008;27:22–27. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e318156caf2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong T, Ormonde S, Gamble G, McGhee CN. Severe infective keratitis leading to hospital admission in New Zealand. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:1103–1108. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.9.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun D, Fernandez V, Miller D, Alfonso EC. Advanced fusarium keratitis progressing to endophthalmitis. Cornea. 2003;22:300–303. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200305000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eifrig CW, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Miller D. Endophthalmitis caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1714–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00572-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KJ, Sun MH, Lai CC, Wu WC, Chen TL, Kuo YH, et al. Endophthalmitis caused by Pseodomonas aeruginosa in Taiwan. Retina. 2011;31:1193–1198. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181fbce5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen YC, Wang CY, Tsai HY, Lee HN. Intracameral voriconazole injection in the treatment of fungal endophthalmitis resulting from keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan R, Bharathi MJ, Shivkumar C, Mittal S, Meenakshi R, Khadeer MA, et al. Microbiological profile of culture-proven cases of exogenous and endogenous endophthalmitis: a 10-year retrospective study. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:945–956. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmar P, Salman A, Kalavathy CM, Kaliamurthy J, Thomas PA, Jesudasan CA. Microbial keratitis at extremes of age. Cornea. 2006;25:153–158. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000167881.78513.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedziak AI, Miller MR, Rapuano CJ, Laibson PR, Cohen EJ. Risk factors in microbial keratitis leading to penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1166–1170. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomholt JA, Ehlers N. Graft survival and risk factors of penetrating keratoplasty for microbial keratitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1997;75:418–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.1997.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee EC, Kwon YH. Graft failure: III. Glaucoma escalation after penetrating keratoplasty. Int Ophthalmol. 2008;28:191–207. doi: 10.1007/s10792-008-9223-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banitt M, Lee RK. Management of patients with combined glaucoma and corneal transplant surgery. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:1972–1979. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness CM, Moshegov C. Post-keratoplasty glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 1988;2 (Suppl:S19–S26. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karesh JW, Nirankari VS. Factors associated with glaucoma after penetrating keratoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:160–164. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkness CM, Ficker LA. Risk factors for the development of postkeratoplasty glaucoma. Cornea. 1992;11:427–432. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- França ET, Arcieri ES, Arcieri RS, Rocha FJ. A study of glaucoma after penetrating keratoplasty. Cornea. 2002;21:284–288. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulks GN. Glaucoma associated with penetrating keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:871–874. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]