Abstract

Few studies have investigated the association of non-dense area or fatty breasts in conjunction with breast density and breast cancer risk. Two articles in a recent issue of Breast Cancer Research investigate the role of absolute non-dense breast area measured on mammograms and find conflicting results: one article finds that non-dense breast area has a modest positive association with breast cancer risk, whereas the other finds that non-dense breast area has a strong protective effect to reduce breast cancer risk. Understanding the interplay of body mass index, menopause status, and measurement of non-dense breast area would help to clarify the contribution of non-dense breast area to breast cancer risk.

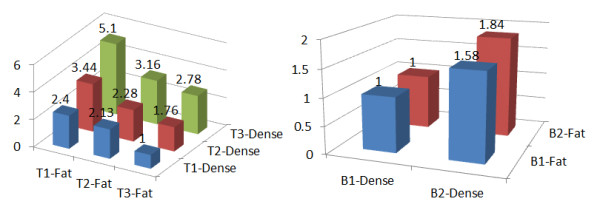

In a recent issue of Breast Cancer Research, two articles investigate the role of the non-dense breast area (fatty breasts) in breast cancer risk [1,2]. Each presents compelling results to show why non-dense breast area measured on mammograms is as informative as dense breast area in regard to future breast cancer risk. Both studies report a strong association with dense breast area and breast cancer risk. However, Pettersson and colleagues [1] report a significant and rather strong negative association of non-dense area and breast cancer risk, whereas Lokate and colleagues [2] report a modest positive association. The two primary results are graphically shown in Figure 1. Can both be right?

Figure 1.

Models of breast cancer risk odds ratios for breast dense area and non-dense (fat) area. A model from Pettersson and colleagues [1] is shown on the left, and a model from Lokate and colleagues [2] is shown on the right. Models are adjusted for age, age of menopause, family history of breast cancer, parity, body mass index, and alcohol use. Additional adjustments for the model from Pettersson and colleagues [1] are age of menarche and alcohol use. Additional adjustments for the model from Lokate and colleagues [2] are height, number of children, and hormone therapy use.

Breast density is determined by the relative amounts of fat and epithelial and connective tissues that appear differently on a mammogram because of differences in x-ray attenuation. Fat appears radiolucent or dark, whereas epithelial and connective tissues are radiographically dense and appear light or white. The percentage of dense area on a mammogram as well as absolute dense breast area and several qualitative measures of breast density are established risk factors for breast cancer [3]. The strength of the risk association depends on the breast density categories being compared. Studies that compare women with at least 75% dense breast area with women with minimal or no dense breast area report relative risks of 4 to 6 [4]. Studies that use comparative groups that are more prevalent, such as lowest and highest quartiles or quintiles of breast density, report relative risks of 2 to 4 [5]. The biologic basis of increased breast cancer risk with increased breast density is unknown but is thought to be related to the higher amounts of collagen, stromal tissue, and, to a lesser degree, breast epithelium found in dense areas [6,7]. One popular theory is that there is an interaction between the stroma and epithelium in the breast and that the increased density of stroma promotes cancer-causing interactions. Conversely, a decrease in the proportion of breast density and increase in the proportion of fat are associated with decreased risk of breast cancer.

Pettersson and colleagues [1] report that the greater the non-dense breast area (regardless of the dense breast area), the lower the breast cancer risk. In other words, fatty breasts have a protective effect on breast cancer risk. Two other studies have shown an inverse association with non-dense breast area though not as strong as that reported by Pettersson and colleagues [1]. Torres-Mejia and colleagues [8] report that non-dense area is inversely associated with breast cancer risk but did not report on its independence from dense breast area. Stone and colleagues [9] found a weaker inverse association with non-dense area than Pettersson and colleagues [1], and the association did not persist when dense breast area was controlled for.

Additional indirect evidence supports the hypothesis that fatty breasts have a protective influence on breast cancer risk. Compared with women with average breast density, women with fatty breasts assessed by Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) density categories are at decreased risk of breast cancer [10]. Moreover, women with fatty breasts are at low risk of breast cancer, regardless of age, menopausal status, family history of breast cancer, history of prior breast biopsy, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use [3,11]. Lastly, women with low breast density are at reduced risk of advanced-stage disease [11]. Thus, the finding by Pettersson and colleagues [1] is consistent with that of prior breast density studies showing that fatty breasts confer a low risk of breast cancer and this beneficial effect appears to be permanent, regardless of the presence of other risk factors.

The results reported by Lokate and colleagues [2], contrary to those of previous studies, show that non-dense breast area is associated with increased breast cancer risk. Why are the results for non-dense area less clear than those for dense breast area? One possible explanation is that the method to quantify non-dense areas differs across studies. Both Lokate and colleagues [2] and Stone and colleagues [9] used mediolateral oblique (MLO) views to quantify breast areas, whereas Pettersson and colleagues [1] and Torres-Mejia and colleagues [8] used craniocaudal (CC) views. This may be an important difference between studies. Total breast area, since it includes a greater amount of superior axillary breast tissue, is larger for MLO views compared with CC views. In MLO views, it is more subjective in regard to where actual breast adipose tissue ends and body subcutaneous adipose tissue begins, potentially leading to greater absolute non-dense breast area. Possibly, the body subcutaneous adipose included in MLO views is not associated with a protective effect because it reflects an increase in body mass index rather than breast adipose tissue. Elevated body mass index has been associated with increased breast cancer risk among postmenopausal women not using hormone therapy [12]. This hypothesis can be tested by stratifying postmenopausal women according to body mass index to determine whether increased non-dense area on MLO views has a strong association with breast cancer risk among normal-weight women and those with increased body mass index. Second, it would be important to know whether non-dense breast area measured on MLO or CC views on the same woman were associated with increased breast cancer risk. Lastly, examining the association of non-dense breast area on MLO views in premenopausal women to determine whether the results reported by Lokate and colleagues [2] in postmenopausal women could be reproduced in premenopausal women would support their findings.

As highlighted by these two articles, important information, in addition to breast density, that can be measured on mammograms could contribute to a better estimate of breast cancer risk. Quantitative measures of dense and non-dense breast area and possibly other image factors need to be standardized if they are to be used in clinical practice.

Abbreviations

CC: craniocaudal; MLO: mediolateral oblique.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

See related research by Petterson et al., http://breast-cancer-research.com/content/13/5/R100, and Lokate et al., http://breast-cancer-research.com/content/13/5/R103

Contributor Information

John A Shepherd, Email: karla.kerlikowske@ucsf.edu.

Karla Kerlikowske, Email: john.shepherd@ucsf.edu.

Acknowledgements

JAS and KK are funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA140286) and the California Breast Cancer Research Program.

References

- Pettersson A, Hankinson S, Willett W, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Tamimi R. Non-dense mammographic area and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R100. doi: 10.1186/bcr3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokate M, Peeters P, Peelen L, Haars G, Veldhuis W, van Gils C. Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: the role of the fat surrounding the fibroglandular tissue. Breast Cancer Res. 2011;13:R103. doi: 10.1186/bcr3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice JA, Cummings SR, Smith-Bindman R, Ichikawa L, Barlow WE, Kerlikowske K. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:337–347. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-5-200803040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, Jong RA, Hislop G, Chiarelli A, Minkin S, Yaffe MJ. Mammographic density, and risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:227–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J, Kerlikowske K, Ma L, Bo F, Duewer F, Wang J, Malkov S, Vittinghoff E, Cummings S. Volume of dense breast tissue and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1473–1482. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo YP, Martin LJ, Hanna W, Banerjee D, Miller N, Fishell E, Khokha R, Boyd NF. Growth factors and stromal matrix proteins associated with mammographic densities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:243–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Sun L, Miller N, Nicklee T, Woo J, Hulse-Smith L, Tsao MS, Khokha R, Martin L, Boyd N. The association of measured breast tissue characteristics with mammographic density and other risk factors for breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:343–349. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Mejia G, De Stavola B, Allen D, Perez-Gavilan J, Ferreira J, Fentiman I, Dos Santos SI. Mammographic features and subsequent risk of breast cancer: a comparison of qualitative and quantitative evaluations in the Guernsey prospective studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1052–1059. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J, Ding J, Warren RM, Duffy SW. Predicting breast cancer risk using mammographic density measurements from both mammogram sides and views. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:551–554. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0976-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlikowske K, Ichikawa L, Miglioretti D, Buist D, Vacek P, Smith-Bindman R, Yankaskas B, Carney P, Ballard-Barbash R. Longitudinal measurement of clinical mammographic breast density improves estimation of breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:386–395. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlikowske K, Cook AJ, Buist DS, Cummings SR, Vachon C, Vacek P, Miglioretti DL. Breast cancer risk by breast density, menopause, and postmenopausal hormone therapy use. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3830–3837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerlikowske K, Walker R, Miglioretti D, Desai A, Ballard-Barbash R, Buist D. Obesity, mammography use and accuracy, and advanced breast cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1724–1733. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]