Abstract

The influence of albumin on the efficacy of a Eu2+-containing complex capable of interacting with human serum albumin (HSA) was investigated at different field strengths (1.4, 3, 7, 9.4, and 11.7 T). Relaxometric measurements indicated that the presence of albumin at higher field strengths (>3 T) did not result in an increase in the relaxivity of the Eu2+ complex, but a relaxation enhancement of 171 ± 11% was observed at 1.4 T. Titration experiments using different percentages (2, 4.5, 6, 10, 15, and 25% w/v) of HSA and variable-temperature 17O NMR measurements were performed to understand the effect of albumin on the molecular properties of the biphenyl-functionalized Eu2+ complex that are relevant to magnetic resonance imaging.

Keywords: cryptate, relaxivity, magnetic resonance imaging, contrast agent, europium, albumin

1. Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a noninvasive imaging modality that can be used to study anatomical structures [1], and the use of ultra-high field strength (≥7 T) magnets enables faster acquisition of MR images with increased spatial resolution [2–4]. However, common contrast agents such as low-molecular-weight Gd3+-containing complexes become less efficient at ultra-high field strengths relative to lower field strengths [5]. Unlike these Gd3+-based contrast agents, Eu2+-containing cryptates have higher relaxivity values at ultra-high field strengths (7 and 9.4 T) than at lower field strengths (1.4 and 3 T) [6, 7].

We hypothesized that the relaxivity of Eu2+-containing cryptates could be increased by using strategies that improve the relaxivity of Gd3+-based agents. One of these strategies is the slowing of molecular-tumbling rate that can be influenced by covalent or noncovalent interactions with macromolecules including proteins [1,8–27]. Human serum albumin (HSA), the most abundant protein in plasma with concentration of ~670 µM or 4.5% (w/v) [16], noncovalently binds to some contrast agents that contain lipophilic moieties [16–25]. McMurry and coworkers reported an increase in relaxivity of over 200% as a result of the noncovalent interaction of albumin with a Gd3+-containing complex functionalized with biphenyl [25]. Because of the work with Gd3+ and the ability to influence the properties of Eu2+ with functionalized cryptands [28], we hypothesized that a cryptand with a biphenyl group would produce a Eu2+ complex that interacts with albumin to result in an increase in relaxivity.

To test our hypothesis, we synthesized biphenyl-modified Eu2+-containing cryptate 1 (Fig. 1), and measured the relaxivity of cryptate 1 in the presence and absence of HSA at different field strengths (1.4, 3, 7, 9.4, and 11.7 T). We compared the resulting relaxivity values to estimates calculated using the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan equations [29]. We also illustrated the effect of albumin on the contrast-enhancing ability of 1 using phantom images acquired at 7 T. Finally, we performed variable-temperature 17O NMR experiments that probed the molecular basis of the relaxivity values of complex 1 in the presence and absence of HSA.

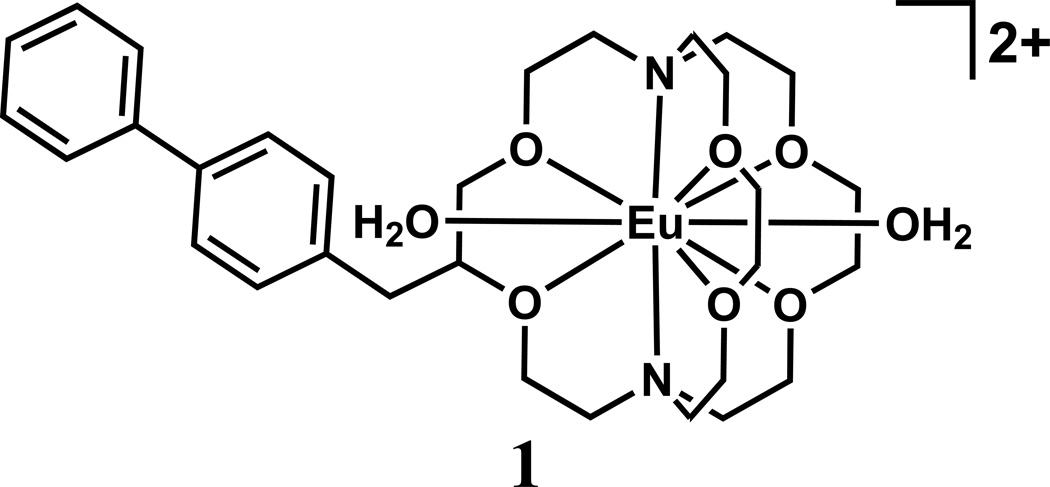

Fig. 1.

Structure of biphenyl-functionalized Eu2+-containing complex 1.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Commercially available chemicals were of reagent-grade purity or better and were used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Biphenyl-functionalized cryptand and cryptate 1 were prepared following a published procedure [6].

2.2. Concentrations

Samples for inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP–MS) were diluted using aqueous nitric acid (2% v/v). Standard solutions were prepared by serial dilution of a Eu standard (High-Purity Standards). ICP–MS measurements were conducted on a PE Sciex Elan 9000 ICP–MS instrument with a cross-flow nebulizer and Scott-type spray chamber.

2.3. Preparation of HSA samples

Stock solutions of HSA (30% w/v) and (35% w/v) were prepared by dissolving 300 and 350 mg of HSA, respectively in 1 mL of 1× degassed phosphate buffered saline (PBS). An aliquot of the stock HSA solution was added to a solution of 1 in degassed PBS to produce the desired concentrations of 1 and HSA.

2.4. Preparation of Sr2+ analogue of 1

A degassed aqueous solution of SrCl2 (1 equiv, 41.2 mM) was mixed with a degassed aqueous solution of the biphenyl cryptand (2 equiv, 34.2 mM). The resulting mixture (1 mM SrCl2 and 2 mM cryptand) was stirred for 12 h at ambient temperature under Ar. Degassed PBS (10×) was added to make the entire reaction mixture 1× in PBS, and stirring was continued for 30 min. The concentration of Sr in the resulting solution was verified by ICP–MS.

2.5. T1 and relaxivity measurements

Longitudinal relaxation times, T1were measured using standard recovery methods with a Bruker Minispec mq 60 (1.4 T) at 60 MHz and 37 °C; a Varian Unity 400 (9.4 T) at 400 MHz and 20 and 37 °C; and a Varian 500S (11.7 T) at 500 MHz and 20 and 37 °C. The slope of a plot of 1/T1 vs concentration of Eu was used to calculate relaxivity. Four to six different concentrations of Eu (0–10 mM) were used, and measurements were repeated 3–9 times with independently prepared samples.

Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) was performed at 3 (Siemens TRIO) and 7 T (ClinScan) using volume coils. The acquisition parameters were as follows: TR = 37 ms, TE = 5.68–31.18 ms, and resolution = 0.5 × 0.5 × 2 mm3 for 3 T; and TR = 21 ms, TE = 3.26–15.44 ms, and resolution = 0.27 × 0.27 × 2 mm3 for 7 T. Multiple flip angles (5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30°) were used in the SWI experiments to allow for the determination of longitudinal relaxation time, T1 [30]. MR images were processed using SPIN software (SVN Revision 1751). Matlab (7.12.0.635 R2011a) was used to generate effective transverse relaxation time, T2*, and corrected T1 maps. The 1/T1 values from the corrected T1 maps were plotted vs the concentration of Eu in the samples to calculate longitudinal relaxivities, r1, as previously reported [6].

2.6. Variable-temperature 17O NMR experiments

Variable-temperature 17O NMR measurements of solutions of 1–HSA (1 mM 125% HSA) and its Sr2+ analogue (1 mM Sr2+–cryptate, 25% HSA) in degassed PBS (pH 7.4) were obtained on a Varian–500S (11.7 T) spectrometer. 17O-enriched water (10% H217O, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc.) was added to samples to yield 1% 17O enrichment. Transverse 17O relaxation rates were measured at 15, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50 °C. The Sr2+ analogue of 1–HSA was used as diamagnetic reference. A/ħ was fixed to −4.1 × 10−6 rad/s [31]. The least-squares fits of the 17O NMR relaxation data were calculated using Origin software (8.0951 B951) following published procedures [32].

3. Results and discussion

Biphenyl-functionalized cryptate 1 was designed based on the structure of Gd3+-based contrast agents that interact with HSA. These Gd3+-containing albumin-binding contrast agents contain lipophilic aryl groups such as the biphenyl moiety that enable them to interact with HSA [16–25]. Therefore, we expected that the lipophilic biphenyl moiety in cryptate 1 would enable investigation of the effect of albumin binding on the relaxivity of Eu2+ at different field strengths.

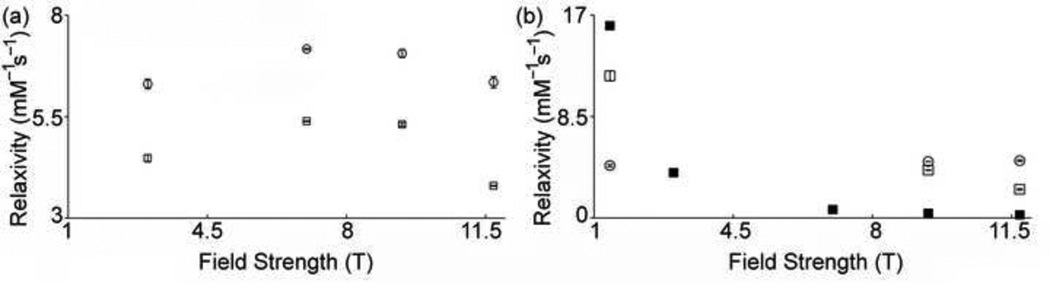

The relaxivity, r1of 1 in PBS in the presence and absence of HSA was measured at multiple field strengths, and because not all of the magnets were capable of variable-temperature measurements, we separated data into Fig. 2a and Fig. 2b so that measurements obtained at each temperature can be compared. In the absence of HSA, the r1 of 1 at 20 °C is higher at 7 and 9.4 T than at 3 T suggesting that this complex is more efficient at ultra-high field strengths than at lower field strengths (Fig. 2a). However, we found that the r1 values at 3 and 11.7 T were not different (Student t test). Moreover, the relaxivity of 1 as a function of field strength is similar to other Eu2+-containing cryptates in the same conditions [7]. In the presence of HSA (4.5% w/v), the relaxivity of 1 decreased by 24.8 ± 0.6% to 40.2 ± 0.2% at field strengths of 3, 7, 9.4, and 11.7 T (Fig. 2a). However, at 37 °C and 1.4 T, the r1 of 1 in the presence of albumin was 171 ± 11% higher than in the absence of HSA (Fig. 2b). An increase of 218% in relaxivity (measured at 37 °C and 0.47 T MHz) was reported by McMurry and coworkers for a Gd3+-containing complex functionalized with biphenyl in the presence of albumin [25]. McMurry’s report and the relaxation data of 1 at 1.4 T indicate that the observed relaxation enhancement of 1 in the presence of HSA is likely due to the interaction of the biphenyl moiety of Eu2+ cryptate with albumin [33]. However, the relaxivity of 1 was 15.2 ± 0.5% and 49.8 ± 0.2% lower in the presence of HSA at 37 °C and 9.4 T and 11.7 T, respectively. The observed decreasing trend in relaxivity of 1 in the presence of HSA at 37 °C as a function of field strength is consistent with the trend obtained by calculating the relaxivity of a slowly rotating Eu2+-containing cryptate at multiple field strengths using the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan equations (Fig. 2b and Supplementary material).

Fig. 2.

(a) Proton longitudinal relaxivity (20 °C, pH = 7.4) of biphenyl-functionalized cryptate 1 in the absence (○) and presence (□) of HSA as a function of magnetic field strength. (b) Proton longitudinal relaxivity (37 °C, pH = 7.4) of biphenyl-functionalized cryptate 1 in the absence (○) and presence (□) of HSA as a function of magnetic field strength. Simulated relaxivity values (■) of a slowly rotating Eu2+-containing complex at 37 °C. Values at 1.4, 3, 7, and 11.7 T without HSA are from reference 6. HSA concentration was 4.5% (w/v). Error bars represent standard error of the mean of 3–9 independently prepared samples.

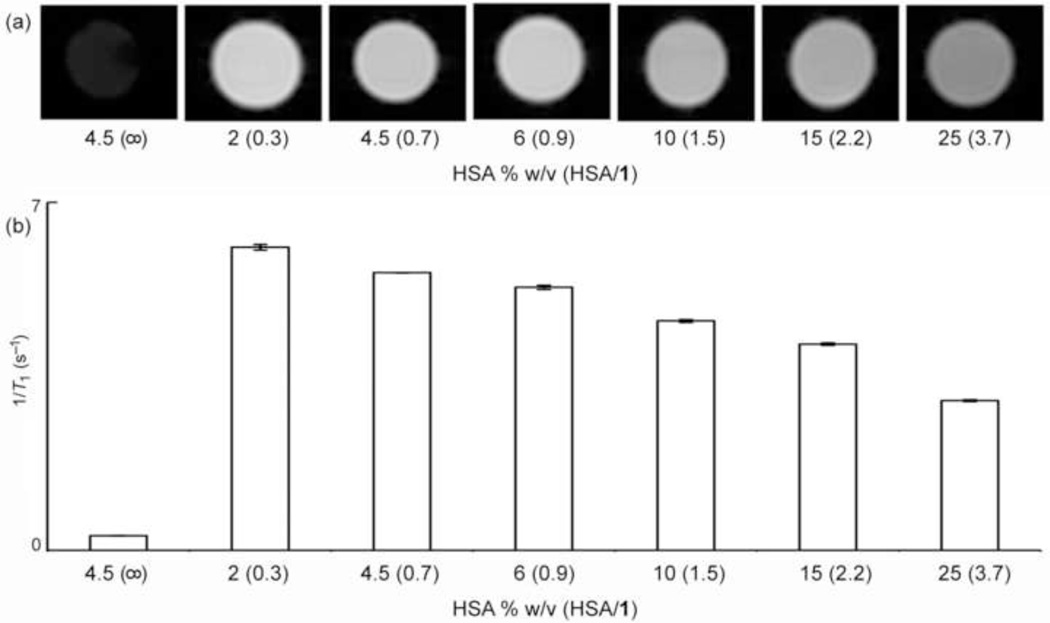

To better understand the effect of albumin on the relaxivity of 1 titration experiments were performed using different percentages (2, 4.5, 6, 10, 15, and 25% w/v) of HSA while keeping the concentration (1 mM) of cryptate 1 constant. In preparation of 1, two equivalents of the biphenyl cryptand were used for each equivalent of Eu2+ to facilitate metalation of the biphenyl cryptand; therefore, the samples 2, 4.5, 6, and 10% HSA have an excess of biphenyl relative to HSA (HSA/1 < 1 except 10% HSA sample) and samples with 15 and 25% HSA have a subcess of biphenyl relative to HSA (HSA/1 > 1). The MR images (Fig. 3a) of 1 with HSA/1 ratios less than one have higher signal intensities as compared to the images of samples with HSA/1 ratios greater than 1. To quantify this observation, the proton longitudinal relaxation rate, 1/T1, of the sample with the lowest HSA/1 ratio is 102.7 ± 0.3% higher than the sample with the highest HSA/1 ratio and 47.0 ± 0.2% higher than the other sample (15% HSA) that has an excess of HSA relative to biphenyl (Fig. 3b). The difference in signal intensity and 1/T1 values among the samples indicate that the presence of albumin affects the relaxivity of complex 1 and does not translate to a higher signal intensity and higher efficacy of 1 at ultra-high fields. These observations support the relaxivity measurements described in Figure 2.

Fig. 3.

(a) T1-weighted MR images of albumin-containing solutions of biphenyl-functionalized cryptate 1 at 7 T and 20 °C. The diameter of the tubes that were used for imaging was 6 mm. Imaging parameters were TR = 21 ms; TE = 3.26 ms; and resolution = 0.27 × 0.27 × 2 mm3. (b) Proton longitudinal relaxation rate (20 °C, pH = 7.4) as a function of % HSA at 7 T. The concentration of cryptate 1 was 1 mM. Error bars represent standard error of the mean of three samples. ano cryptate.

To explain the observations of relaxivity, we performed variable-temperature 17O NMR measurements using a sample of 1 in PBS and 1 in PBS with 25% HSA. We chose 25% HSA because the majority of 1 was expected to be bound to albumin at this percentage [25], and the 17O NMR data obtained from this sample would be representative of the molecular properties of cryptate 1 that is bound to HSA. The molecular properties that influence relaxivity that were studied using variable-temperature 17O NMR spectroscopy were the residence lifetime of bound water molecules, τm298; the water-exchange rate, kex298 = 1/τm298; and the number of inner-sphere water molecules, q (Table 1). While the residence lifetime of bound water of cryptate 1 was not different (Student t test) in the presence and absence of albumin, the number of inner-sphere water molecules was reduced from two to one upon addition of albumin indicating that the observed decrease in relaxivity for cryptate 1 in the presence of albumin at 3, 7, 9.4, and 11.7 T is likely caused by the displacement of inner-sphere water molecules from the Eu2+ complex. Moreover, the residence lifetime of bound water was not different in the presence or absence of albumin suggesting that protein side chains do not hinder the remaining bound water molecule from exchanging with the bulk solvent. With the water-exchange rate and the number of inner-sphere water molecules of 1 in the presence of HSA remaining constant at different field strengths, the relaxivity enhancement observed at 1.4 T likely can be attributed to the enhanced contribution of rotational correlation rate at this field strength.

Table 1.

Results of 17O NMR experiments of cryptate 1 with and without albumin.

Reference 6,

HSA concentration was 25% (w/v)

4. Conclusions

The relaxation profile of Eu2+-containing cryptate 1 in the absence of albumin shows that cryptate 1 is more efficient at higher field strengths (7 and 9.4 T) than at lower field strengths (1.4 and 3 T). MR images and 1/T1 values of samples with different HSA/1 ratios suggest that possible interaction of 1 with HSA occurs, but this interaction does not lead to an increase in relaxivity of Eu2+ at higher field strengths (≥3 T). However, in the presence of albumin, an increase in relaxivity of 1 is only observed at 1.4 T likely due to decreased rotational correlation rate values, and a decrease in relaxivity was observed at 3, 7, 9.4, and 11.7 T because of a decreased water-coordination number. These data are in agreement with calculations made using the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan equations. Studies using different lengths of linkers between the biphenyl and cryptate could provide a good insight on the influence of albumin interaction on the relaxivity of cryptate 1. Also, binding a Eu2+-containing cryptate to different sizes of macromolecules could provide a better understanding on the effect of macromolecular binding on the relaxivity of Eu2+-containing cryptates at higher fields. These studies are currently underway in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The influence of albumin on a Eu2+-containing complex was investigated

Relaxivity increased at 1.4 T relative with albumin

Relaxivity decreased at 3, 7, 9.4, and 11.7 T with albumin

The number of inner-sphere water molecules decreased in the presence of albumin

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeremiah Moore for helpful discussions. This research was supported by startup funds from Wayne State University (WSU) and by the National Institutes of Health (R00EB007129). J. G. was supported by a Paul and Carol Schaap Graduate Fellowship and a Rumble Fellowship from WSU, and M. J. A. gratefully acknowledges a Schaap Faculty Scholar Award. We thank Latif Zahid and Yimin Shen for performing imaging experiments.

Abbreviations

- ICP–MS

inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- HAS

human serum albumin

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Villaraza AJL, Bumb A, Brechbiel MW. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:2921–2959. doi: 10.1021/cr900232t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moser E. World J. Radiol. 2001;2:37–40. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt D, Boster A, Pei W, Wohleb E, Jasne A, Zachariah CR, Rammohan K, Knopp MV, Schmalbrock P. Arch. Neurol. 2010;67:812–818. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blow N. Nature. 2009;458:925–928. doi: 10.1038/458925a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caravan P, Farrar CT, Frullano L, Uppal R. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2009;4:89–100. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia J, Neelavalli J, Haacke ME, Allen MJ. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:12858–12860. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15219j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia J, Kuda-Wedagedara ANW, Allen MJ. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012;2012:2135–2140. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201101166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armitage FE, Richardson DE, Li KCP. Bioconjugate Chem. 1990;1:365–374. doi: 10.1021/bc00006a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aime S, Botta M, Crich SG, Giovenzana G, Palmisano G, Sisti M. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:192–199. doi: 10.1021/bc980030f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicolle GM, Tóth É, Eisenwiener K-P, Mäcke HR, Merbach AE. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002;7:757–769. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0353-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres S, Martins JA, André JP, Geraldes CFGC, Merbach AE, Tóth É. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:940–948. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laus S, Sour A, Ruloff R, Tóth É, Merbach AE. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:3064–3076. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang JJ, Yang J, Wei L, Zurkiya O, Yang W, Li S, Zou J, Zhou Y, Maniccia ALW, Mao H, Zhao F, Malchow R, Zhao S, Johnson J, Hu X, Krogstad E, Liu Z-R. J. Chem. Am. Soc. 2008;130:9260–9267. doi: 10.1021/ja800736h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kundu A, Peterlik H, Krssak M, Bytzek AK, Pashkunova-Martic I, Arion VB, Helbich TH, Keppler BK. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2011;105:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avedano S, Tei L, Lombardi A, Giovenzana GB, Aime S, Longo D, Botta M. Chem. Commun. 2007:4726–4728. doi: 10.1039/b714438e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caravan P, Cloutier NJ, Greenfield MT, McDermid SA, Dunham SU, Bulte JWM, Amedio JC, Jr, Looby RJ, Supkowski RM, Horrocks W DeW, Jr, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3152–3162. doi: 10.1021/ja017168k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henoumont C, Vander Elst L, Laurent S, Muller RN. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009;14:683–691. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0481-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gianolio E, Giovenzana GB, Longo D, Longo I, Menegotto I, Aime S. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:5785–5797. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ou M-H, Tu C-H, Tsai S-U, Lee W-T, Liu G-C, Wang Y-M. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:244–254. doi: 10.1021/ic050329r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aime S, Botta M, Fasano M, Crich SG, Terreno E. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1996;1:312–319. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aime S, Chiaussa M, Digilio G, Gianolio E, Terreno E. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999;4:766–774. doi: 10.1007/s007750050349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parac-Vogt TN, Kimpe K, Laurent S, Elst LV, Burtea C, Chen F, Muller RN, Ni Y, Verbruggen A, Binnemans K. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:3077–3086. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aime S, Gianolio E, Terreno E, Giovenzana GB, Pagliarin R, Sisti M, Palmisano G, Botta M, Lowe MP, Parker D. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000;5:488–497. doi: 10.1007/pl00021449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumas S, Troughton JS, Cloutier NJ, Chasse JM, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. Aust. J. Chem. 2008;61:682–686. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nivorozhkin AL, Kolodziej AF, Caravan P, Greenfield MT, Lauffer RB, McMurry TJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:2903–2906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strijkers GJ, Mulder WJM, van Heeswijk RB, Frederik PM, Bomans P, Magusin PCMM, Nicolay K. MAGMA. 2005;18:186–192. doi: 10.1007/s10334-005-0111-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson EA, Isaacman S, Peabody DS, Wang EY, Canary JW, Kirshenbaum K. Nano Lett. 2006;6:1160–1164. doi: 10.1021/nl060378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamage N-DH, Mei Y, Garcia J, Allen MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:8923–8925. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Chem. Rev. 1999;99:2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haacke EM, Brown RW, Thompson MR, Venkatesan R. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Physical Principles and Sequence Design. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1999. pp. 451–460. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burai L, Scopelliti R, Tóth É. Chem. Commun. 2002:2366–2367. doi: 10.1039/b206709a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urbanczyk-Pearson LM, Femia FJ, Smith J, Parigi G, Duimstra JA, Eckermann AL, Luchinat C, Meade TJ. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:56–68. doi: 10.1021/ic700888w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.To confirm that the increase in relaxivity was not due to nonspecific binding of the cryptate with HSA, we repeated the measurement at 1.4 T using Eu2+[2.2.2]cryptate (without biphenyl) and observed a relaxivity value of 3.31 ± 0.07 mM−1s−1.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.