Abstract

Background

Recent studies highlighting the psychological benefits of medical treatment for dermatological skin conditions have demonstrated a clear role for medical therapy in psychological health. Skin conditions, particularly those that are overtly visible, such as those located on the face, neck, and hands, often have a profound effect on the daily functioning of those affected. The literature documents significant emotional benefits using medical therapy in conditions such as acne, psoriasis, vitiligo, and rosacea, but there is little evidence documenting similar results with the use of cosmetic camouflage. Here we present a review highlighting the practical use of cosmetic camouflage makeup in patients with facial skin conditions and review its implications for psychological health.

Methods

A search of the Medline and Scopus databases was performed to identify articles documenting the emotional benefit of cosmetic camouflage.

Results

Cosmetic camouflage provides a significant emotional benefit for patients with facial skin conditions, and this is substantiated by a literature review and personal experience. More clinical studies are needed to assess and validate the findings reported here.

Conclusion

Patients with visible skin conditions have increased rates of depression, anxiety, and decreased self-esteem. It is prudent for us to consider therapies that can offer rapid and dramatic results, such as cosmetic camouflage.

Keywords: facial skin conditions, psychological health, emotional benefits, cosmetic camouflage, makeup

Introduction

Visible skin conditions are often a source of emotional concern for patients. Perseverance with treatment regimens is required in order to see noticeable improvements; however, many patients desire an immediate effect. Cosmetic camouflage is an easy to teach and learn technique that utilizes makeup to disguise skin lesions. Following application of specialized products, an immediate improvement in skin appearance and patient contentment is often appreciated. Currently, there is a paucity of studies documenting the benefits and efficacy of cosmetic camouflage for patients with disfiguring skin lesions. We see immediate and satisfying results with the use of camouflage in our patients. This article reviews the psychological effects of facial skin conditions in the literature and introduces practical techniques of cosmetic camouflage for the treatment of skin lesions.

For this review, we conducted a literature search of the PubMed and Scopus databases in order to identify studies evaluating the quality of life (QoL) in patients after instituting camouflage therapy for facial skin conditions. Medical subject headings (MeSH) terms used were “ cosmetic camouflage,” “make up,” “QoL,” “emotional benefit,” “rosacea,” “psoriasis,” “acne,” “vitiligo,” “melasma,” and “facial skin lesions”. Articles documenting improvement in QoL measures based on validated clinical evaluation scales were selected and reviewed. Seven studies were identified and are highlighted in this review. Furthermore, the camouflage products included were identified from our prior clinical encounters, consultations with other experts in the field, and from the clinical studies or case reports reviewed. Detailed information about products was obtained from product package inserts, consumer information, and company websites.

Emotional consequences of dermatological conditions

Dermatological conditions, particularly those located on the face, such as acne, psoriasis, vitiligo, and rosacea, can be emotionally and psychologically disfiguring. Patients with acne are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, decreased self-esteem, and have suicidal ideation.1–3 This is especially important during the formidable years of adolescence, where psychological distress can cause significant social problems. Psoriasis, a common autoimmune inflammatory skin disease, decreases the QoL of those affected and is also a notable risk factor for suicide.4–6 Additionally, patients with rosacea and vitiligo, and other dermatological conditions that manifest on the face, also experience significant psychological distress and impaired self-esteem leading to a decreased QoL.7–9 The degree of visible depigmentation in vitiligo, particularly when localized to the face, head and neck, and genitalia, correlates with psychological impact.10

Although these conditions do not cause a direct physical impairment, with the rare exception of ocular rosacea causing vision disturbances, there is a profound psychosocial impact. One study aimed to quantify the burden of vitiligo as compared with psoriasis by estimating the health-related QoL in the Dutch-speaking Belgian population.7 Patients with vitiligo (n = 119) and psoriasis (n = 162) were included in a postal survey, and QoL was assessed by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), in order to validate and compare differences between the two skin conditions. The overall mean DLQI score for vitiligo was lower than for psoriasis (4.95 versus 6.26; P = 0.01). Further, patients with vitiligo experienced less impairment from symptoms and treatment of the disease (P < 0.001). Nonetheless, this study quantified the burden on QoL that results from vitiligo, and indicated that the most affected domains influenced were feelings, clothing, social and leisure activities, and daily routine. These results underscore the need for adequate medical therapies, because they will likely also improve a patient’s QoL.

For example, treatments for rosacea improve both QoL and symptomatology.11,12 A study using the pulsed dye laser (595 nm) in 16 patients with erythematotelangiectatic rosacea having both persistent erythema and dysesthetic symptoms were given a questionnaire evaluating both the DLQI and skin symptoms (flushing, burning, itching, dryness, swelling, and skin sensitivity) using visual analog scales.11 Treatment with purpuragenic fluences (7 mm spot size, 10 J/cm2, 1.5 msec) demonstrated significant improvements in erythema, the abovementioned symptoms, and QoL.

The face is of paramount importance to body image and self-esteem. Patients with facial skin conditions have an increased risk of depression and suicide, making it necessary for the physician to initiate therapies and alternatives to improve the medical condition while minimizing the cosmetic appearance.13 Facial lesions can result in a disruption of overall well-being, including impaired social and emotional functioning and productivity at work or school.14 In one review, 16 patients (seven men, nine women) who committed suicide after presenting with dermatological problems were described.13 The patients either had a body image disorder (dysmorphophobia) or acne. This was one of the first articles documenting the need for early therapeutic intervention in patients with long-standing and debilitating skin diseases because the risk of depression and suicide was highlighted. Interestingly, patients with nondermatological disease and women with facial complaints were the most depressed and had the highest risk for suicide. Facial scarring in men was identified as a “risk factor” for suicide.

Mealsma, characterized by hyperpigmented macules/patches in sun-exposed areas (particularly on the face), is another skin condition with known significant psychological effects, such as feelings of embarrassment, anxiety, depression, and social isolation.14,15 After an extensive literature review seeking information regarding the impact of melasma on health-related QoL in affected patients, it was determined that there was a deleterious impact on social life, emotional well-being, physical health, and financial status in Hispanic women.16

The literature provides an abundance of evidence suggesting facial skin conditions are both physically and emotionally disfiguring, with patients increasingly searching for safe, effective, and immediate medical and cosmetic treatments.

Importance of cosmetic camouflage

Many patients seeking a dermatological consultation have already utilized prescription, over-the-counter, and/or home remedies to mitigate the appearance of facial lesions. Typically, these patients report having skin resistant to therapy or note an improvement with subsequent recurrence during maintenance therapy. As a consequence, by the time of dermatological consultation, the patient is frequently frustrated and has started to lose confidence in the ability of the practitioner to provide resolution (or improvement for that matter) in their skin condition. Patients desire immediate therapeutic and cosmetic results when initiating medical treatment, and studies have shown the majority of failures result from patients who are noncompliant with topical application (treatment plans).17,18

In the majority of cases, immediate clinical measures and cosmesis are not feasible because systemic and topical therapies may take several weeks to months of consistent use to achieve noticeable improvement.19 Eczema may improve dramatically with application of topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, or even emollients on the face, but acne may worsen initially upon treatment initiation and take more time to achieve acceptable results.20,21 Vitiligo is often resistant to therapies, including topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and laser or light therapies.22 Additionally, side effects from various treatment modalities may limit long-term use and result in clinically significant relapse or inadequate response.23,24

Treatments for rosacea can achieve rapid results in papulopustular lesions with the initiation of oral anti-inflammatories such as tetracycline antibiotics, topical metronidazole, and/or azelaic acid, but the associated erythema and telangiectasias do not respond significantly to oral and/or topical therapies, requiring multiple treatments with the vascular pulsed dye laser (580–590 nm) for efficacy.25,26 Results in clinical trials using the vascular pulsed dye laser for the treatment of erythema in rosacea, blood vessel dilation/growth in hemangiomas and telangiectasia, as well as hemosiderin deposition from capillaritis are excellent; however, purpura, prolonged erythema, late-onset hypopigmented macules, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation are complications that require serious consideration prior to therapy, especially in the patient with cosmetic concerns.27–31 Although patients are often dissatisfied knowing that there are no “quick fixes” available, it is important that there is a clear discussion regarding the planned therapeutic regimen and the importance of close clinical follow-up, and that meticulous commitment to treatment be emphasized by the practitioner.

Cosmetic camouflage is a technique using makeup to disguise disfiguring skin lesions immediately, with the intention of normalizing the appearance of the skin32 ( Figure 1). This technique uses specialized products, including cover creams, liquids, and powders, that when applied in a systematic way, can rapidly disguise any areas of visible change. The products differ from conventional cosmetics in that they are waterproof and opaque, allowing adherence to textured skin, including scarred or diseased areas.33 Additionally, the products are available in a multiplicity of shades in order to match every skin color and skin condition.34 As an added benefit, newer brands may offer products that contain ingredients providing sun protection to shield against aging (photodamage) and decrease inflammation. Most mainstream products are of low allergenic potential, which is particularly helpful in patients with hypersensitive skin conditions, like rosacea or eczema. Perhaps the most notable benefit of cosmetic camouflage is the immediate results and instant gratification that can be achieved after application of the product (Figure 2A and B). These products are also easily accessible, affordable, and require minimal training for the patient.

Figure 1.

Patient with melasma after half-face treatment with cosmetic camouflage (left face treated).

Note: Notice the significant difference in skin color and texture on the right side of the face as compared with the left, with normalization of the skin texture and tone.

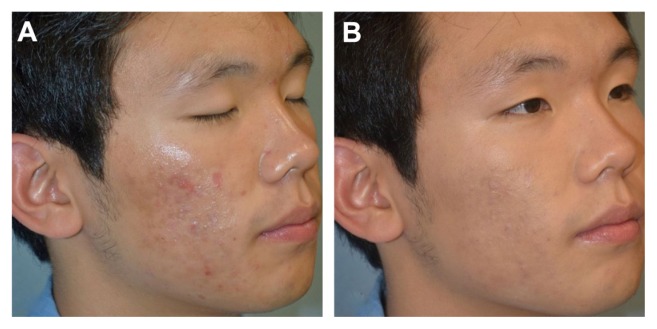

Figure 2.

Severe acne (A) before and (B) after treatment with cosmetic camouflage prior to initiation of medical therapy.

Note: A noticeable and immediate improvement is seen.

Product availability

There are a myriad of brands, with various products and formulations currently available for cosmetic camouflage (Table 1). To determine the best suited products, accurate evaluation of a patient’s skin type and disorder is essential. Further, the patient’s desire and ability (both financial and in terms of time commitment) are important considerations. The best camouflage cosmetics are ones that are natural-looking, waterproof, easy to apply, long-lasting, nonirritating, and affordable.34 Each line offers unique products, and it is often the preference of either the camouflage therapist or the patient when selecting a brand to use. Patients may choose products based on availability, pricing, and available shades, but the physician may desire other characteristics, such as particular ingredients or the ability to help treat and cover without exacerbating the underlying condition. For example, the ClearprepFX Matte Foundation Primer and Anti-Acne Treatment (CoverFX Skin Care Inc, Ontario, Canada) is marketed as paraben-free, but is also oil- and fragrance-free, which is useful in hypersensitive skin conditions. Additionally, the willow bark extract in the product may help treat any underlying acne. Willow bark extract contains a source of natural salicylic acid-like ingredients having similar clinical effects to B-hydroxy acids acid without the associated irritation.35 It is known that salicylic acid enhances cell turnover by promoting exfoliation (giving a smoothing effect), has antimicrobial properties, and is lipid-soluble, allowing for deeper penetration into the stratum corneum. Further, due to its lipophilicity, willow bark extract (similar to salicylic acid) may also help to reduce acne lesions, exfoliate the skin, and reduce sebum buildup.

Table 1.

Popular coverage foundations commonly available*

| Product | Unit price** | Key ingredients | Added benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoverFX Total Cream Foundation SPF 30 |

$42.00 | Sunscreen actives (octinoxate 7.5%, octocrylene 5%, oxybenzone 2%), bisabolol (chamomile), vitamin E (tocopherol), carnauba wax, and beeswax | For all skin types; free of oil, fragrance, and parabens; noncomedogenic; provides an environmental shield from wind, sun, and pollution; sun protection; full coverage for various skin conditions from acne and rosacea to post-surgical bruising, vitiligo, and tattoos; 2-in-1 concealer plus foundation; available in over 30 shades; DermaFix technology giving water resistance and the ability to build coverage in problem areas |

| Dermablend Cover Cream SPF 30 |

$34.00 | Sunscreen active titanium dioxide, mineral oil, talc, beeswax, kaolin, Copernicia cerifera (carnauba) wax | Medium coverage for minor-to-moderate facial skin flaws; available in over 10 shades; lightweight texture guarantees a nonheavy feel; noncomedogenic/nonacnegenic; allergy-tested; fragrance-free |

| Dermablend Smooth Indulgence SPF 20 Foundation |

$30.00 | Sunscreen active titanium dioxide, water, dimethicone, glycerine, methylparaben | Full coverage for moderate-to-severe skin flaws; soft and velvety smooth feeling; smudge-resistant; allergy-tested; noncomedogenic/nonacnegenic; fragrance-free |

| Dermacolor Light Camouflage Cream |

$30.00 | Vitamin E (tocopherol), bisabolol (chamomile), avocado, perhydro-sqalene oil | Highly pigmented makeup for maximum correction and coverage; waterproof; available in over 16 shades |

| Covermark Facemagic SPF 20 |

$25.00 | Sunscreen actives (octyl methoxycinnamate 7.5%, benzophenone 2.5%, titanium dioxide), mineral oil, beeswax, talc, dimethicone, propylparaben | Hypoallergenic; noncomedogenic; smudge-proof; hydrating; available in over 15 shades |

| Covermark Classic Cover |

$25.00 | Sunscreen active titanium dioxide, mineral oil, beeswax, magnesium carbonate, iron oxides, propylparaben, fragrance | Full coverage for serious skin flaws or discoloration; opaque coverage; waterproof; safe for sensitive skin; available in over 30 shades |

| Cover Blend by Exuviance Concealing Treatment Makeup SPF 20 |

$30.00 | Sunscreen actives (titanium dioxide, zinc oxide), cyclomethicone, hydrogenated castor oil, acrylatedimethicone copolymer, vitamin E (tocopheryl acetate), stearic acid, methylparaben | Velvety cream suitable for all skin types including: skin in need of extra coverage; opaque; smudge-proof; gluconolactone (polyhydroxy acid) for antioxidant effect |

| Laura Mercier Secret Camouflage |

$28.00 | Paraffin, Euphorbia cerifera (candelilla) wax, methacrylate, carnauba wax, vitamin E (tocopherol), retinyl palmitate, silica, Matricaria recutita (chamomile) flower extract, honey extract, sunscreen active titanium dioxide | Two-shade system: one to match the skin’s depth of color and one to match the skin’s undertone; high level of pigment for full coverage |

Notes:

All information obtained from manufacturer websites;

approximate cost of smallest available size.

Another product, The CoverFX Total Coverage Cream Foundation SPF 30, is a maximum coverage foundation with SPF (octinoxate 7.5%, octocrylene 5%, and oxybenzone 2%) that also has added cosmetic ingredients to enhance benefits while giving full coverage. The constituents of this product are bisabolol and vitamin E. Bisabolol is derived from the essential oil of the German chamomile (Matricaria recutita) and has been noted to have anti-irritant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties. Vitamin E is a known antioxidant that is thought to provide protection from inflammation, as well as to soothe the skin and promote tissue repair after injury.

Dermablend Professional (Dermablend, Ridgefield, NJ) offers popular camouflage makeup products, including primers, foundations, concealers, and powders, in numerous shades, ranging from fair to dark.36 Products are marketed as noncomedogenic, nonallergenic, fragrance-free, and smudge-resistant for up to 12 hours. Dermablend products may be purchased in packages geared toward specific skin conditions, such as age spots, birthmarks, bruising/post-procedure, freckles, dark under-eye circles, hyperpigmentation, lupus, rosacea, post-surgical redness, scars, spider veins, tattoos, trichoepitheliomas, syringomas, vitiligo, and uneven skin tones. The Dermablend SkinPerfector Pigment Correcting Primer is another example of a cosmetic product with added ingredients for additional benefits. Makeup primers allow for effortless makeup application without slippage and for longer and even wearing of foundation. This primer has ceramides to help replenish damaged epidermal barrier, as well as lipohydroxy acid, a derivative of salicylic acid, which helps to exfoliate dead skin cells to unblock pores and even skin tones.

Integration into practice

Camouflage therapists (makeup artists) are product specialists who are specifically trained in the application of makeup and education of patients and health care providers.34 The majority of mainstream cosmetic retail shops have camouflage therapists available to help individualize the patient’s home regimen that can work concurrently with prescribed medical therapies. Cosmetic therapists should serve as a beneficial resource for physicians and patients who desire camouflage therapy; however, few physicians are trained themselves in product availability, cost, application technique, and unique situations requiring multiple products and different brands for overlapping conditions, larger facial lesions, conditions requiring more coverage, or the concurrent use of other topical therapies. Thus, a barrier often exists that prevents patients from obtaining immediate improvement, as dermatologists are poorly trained or educated regarding the availability and use of cosmeceuticals, despite the demand for this information and these services. It is important to note that we suggest the use of makeup products as a supplement and adjunct to medical treatments, as a “bridge therapy” until traditional methods begin to have a noticeable clinical and resultant cosmetic effect (Figure 3A and B). Furthermore, increased awareness through clinician education is necessary, especially during residency training, when learning/studying the importance of skin care regimens in managing chronic and distressing skin conditions is refined.

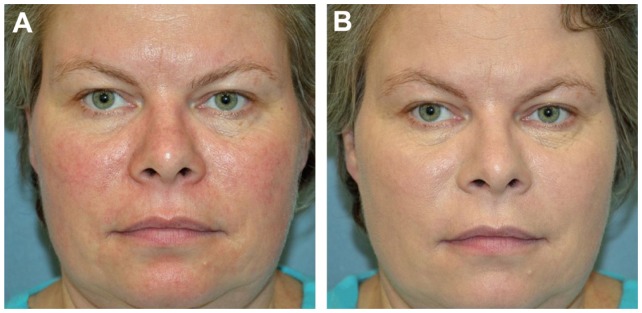

Figure 3.

Patient with (A) noticeable erythema and telangiectasias on the cheeks due to rosacea, and (B) immediate improvement without irritation after makeup application prior to initiation of pulsed dye laser therapy.

Skin-specific grading scales

The importance of selectively integrating cosmetic camouflage into a treatment regimen by a dermatologist is based on the fact that treatment of visible skin conditions can provide patients with emotional benefits, thus improving their QoL.37,38 There are numerous well established evaluation scales used in clinical trials which assess the psychological effect of skin conditions and how treatments can provide significant benefit.39 The two most commonly used scales are the DLQI and the Skindex. The DLQI is a validated, self-administered, user-friendly questionnaire for routine clinical use that assesses QoL measures in patients with any dermatological disease.40 Although the DLQI is frequently used in randomized, controlled, clinical trials in dermatology, it can be administered in routine clinical practice to aid in clinical consultation, evaluation, and decision-making. It comprises 10 questions concerning the patients’ perception of the impact of their skin disease on different aspects of QoL, including symptoms and feelings, daily activities, clothing, leisure, work and school, personal and sexual relationships, and the side effects of treatment over the past week. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale (0, not at all/not relevant; 1, a little; 2, a lot; 3, very much). Scores of individual items (0–3) are added to yield a total score of (0–30), with higher scores indicative of a greater impact on QoL.

The original Skindex scale was developed to assess the impact of skin disease on patient QoL, in the hope of assisting in clinical judgment of disease severity. The first scale was a 61-item self-administered survey, comprising a total of eight scales, each addressing a different component of a person’s life, including cognitive effects, social effects, depression, fear, anger, physical discomfort, and physical limitations.41 The items are standardized from 0 (no effect) to 100 (maximal effect), with the overall score reflecting the average of responses to items addressing that specific construct. The Skindex was validated to address disease severity independent of a physician’s judgment. The Skindex has been revised by decreasing the number of items in the questionnaire. Initially a 29-item version of the scale was created and validated, followed by a 16-item version.42,43 This condensed 16-item, single-page survey asks patients about any bother they experience and is reported as three scales, ie, symptoms, emotions, and functioning. Both the DLQI and Skindex are currently available in many languages and are used by researchers to determine and compare influences on QoL across different cultures.44–48

Disease-specific grading scales have also been developed to quantify the psychological impact of specific characteristics or symptoms of cutaneous diseases. These are particularly useful for conditions that have profound known psychological effects and can help to assess the emotional benefit of treatments on a patient’s overall quality of life. The most studied conditions include acne (Cardiff Acne Disability Index, Acne QoL, Assessment of the Psychological and Social Effects of Acne), psoriasis (Psoriasis Disability Index, Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory, Impact of Psoriasis Questionnaire), and vitiligo (Patient Benefit Index), although melasma (Melasma QoL Scale) and rosacea (Rosacea Specific QoL) have recently become important conditions to consider as having a life impact.7,14,49–52

Every clinical study has shown a clear improvement in disease symptoms and psychological effects with medical therapy, although more randomized, double-blind controlled studies are necessary in order to validate existing scales, expand to other diagnoses (eg, chronic hand eczema causing pain and change in functionality, severe atopic dermatitis causing pruritus and interfering with sleep and work, conditions affecting the anogenital areas causing lack of sexual interaction and embarrassment) and consider more detailed screenings (eg, age groups, comorbidities, and multiple conditions).

Use of cosmetic camouflage

Medical therapy can have a profound effect on QoL and well-being, and this should be an integral consideration when making therapeutic decisions and following patients whose lives are affected by their skin condition. We believe cosmetic camouflage should be intimately integrated into routine practice. Despite evaluation of improvement in QoL following therapeutic regimens being of critical importance to the field of dermatology, there are only a handful of studies evaluating the emotional benefit of cosmetic camouflage in various dermatological diseases. Interestingly, there is limited use of cosmetic camouflage in clinical practice, despite reports demonstrating that proper use and integration of makeup with concurrent medical therapy can dramatically affect QoL in patients suffering from various nonlethal skin conditions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical studies or reports of cosmetic camouflage for skin conditions

| Title of study | Condition(s) | Assessment scale(s) used | Conclusion(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmetic camouflage advice improves QoL53 | Pigmentary disorders, scars, vascular disorders | DLQI | When assessed at one month, attendance at a cosmetic camouflage clinic appeared to improve QoL scales |

| Camouflage for patients with vitiligo vulgaris improved their QoL54 | Vitiligo | DLQI | Data support the idea that camouflage for patients with vitiligo not only covers the white patches but also improves their QoL |

| Effects of skin care and makeup under instruction from dermatologists on the QoL of female patients with acne vulgaris55 | Acne | DLQI, WHO QoL-26 | Suggests use of skin care cosmetics to complement medical treatments for acne as overall scores on both the DLQI and WHO QoL-26 improved significantly |

| Make-up improves the QoL of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments56 | Acne | Skindex-16, GHQ 30, WHO QoL-26, STAI, POMS, VAS | QoL scores of all scales greatly improved, suggesting dermatologists should encourage acne patients to utilize appropriate makeup to improve QoL |

| Decorative cosmetics improve the QoL in patients with disfiguring skin diseases37 | Acne, rosacea, chronic discoid lupus, vitiligo | DLQI | Mean DLQI scores dropped significantly, suggesting that decorative cosmetics can complement the treatment of disfiguring skin diseases |

| Corrective camouflage in pediatric dermatology57 | Acne, vitiligo, Becker’s nevus, striae distensae, allergic contact dermatitis, post-surgical scarring | N/A | All patients were satisfied with cosmetic cover results, making it a valid adjunctive therapy for use during traditional longterm treatment and as a therapeutic alternative in patients for whom conventional therapy is ineffective |

| QoL and stigmatization profile in a cohort of vitiligo patients and effect of use of camouflage10 | Vitiligo | DLQI, stigmatization questionnaire | Camouflage can be recommended, particularly in patients with higher DLQI scores |

| Waterproof camouflage age for vitiligo of the face using Cavilon 3M as a spray58 | Vitiligo | N/A | Waterproof camouflage for vitiligo is an easy and rapid treatment option. It is safe when applied to the skin, and very useful for patients with vitiligo of the face, especially for swimmers |

Abbreviations: QoL, quality of life; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; WHO QoL-26, World Health Organization Quality of Life; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; POMS, Profile of Mood States; VAS, visual analog scale.

A three-center study of over 135 patients (82 total completions) evaluated the effect on perceived QoL using a dermatology- specific QoL measure (ie, DLQI), before and after one month of visits to a cosmetic camouflage clinic.53 Patients were asked to complete the DLQI (without assistance) and results from individuals who answered both questionnaires were entered into a database and subjected to statistical analysis. The three main diagnostic categories were disorders of pigmentation (hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, including melasma, lentigines, café-au-lait macules, and vitiligo, n = 24), scarring (n = 18), and vascular skin conditions (including spider veins, telangiectasias and port wine stains, n = 11). There was a significant difference in DLQI scores before and one month after the cosmetic camouflage clinic appointments (P = 0.0001). The mean DLQI score was 9.1 before cosmetic camouflage advice and 5.8 when assessed one month later (a higher score reflects larger impact on QoL, maximum score 30). The domains with the highest scores included those that assessed embarrassment and self-consciousness resulting from skin lesions, as well as the influence of skin disease on clothing and leisure activities. The questions with the greatest change as a percentage of the initial score concerned impact on sexual (85% reduction) and interpersonal (73% reduction) relationships. Overall, the authors concluded that the presence of visible skin lesions can result in significant psychological impairment, which effects self-esteem, social and sexual relationships, and the ability to secure employment. Furthermore, makeup products that serve as a concealer are beneficial in clinical practice.

A similar study asked 20 female patients with skin diseases affecting their face (acne, n = 8; rosacea, n = 9; chronic discoid lupus, n = 2; vitiligo, n = 1) to complete the DLQI prior to makeup application and 2 weeks after application of daily decorative cosmetics (Unifiance, La Roche-Posay, France) by a cosmetician.37 The makeup was well tolerated without side effects, completely masked the unwanted coloration, and resulted in significant amelioration of the appearance of the disease. Mean DLQI scores dropped significantly from 9.2 to 5.5 (P = 0.0009), indicating an improvement in QoL. The authors concluded that, despite a small sample size and various skin conditions, the use of decorative cosmetics in subjects with disfiguring skin disease is an effective, well tolerated treatment to help increase QoL and that decorative cosmetics should complement medical treatment protocols. Although not mentioned in this study, patients with acne showed the most significant changes in overall QoL (7.8 versus 2.8; P = 0.0078), and similar findings were described in another study utilizing makeup techniques in the treatment of acne.56

In the abovementioned study, the authors questioned whether it was appropriate for dermatologists to discourage female patients with acne from applying makeup, given that cosmetic products have been described as aggravating factors in acne and may interfere with proposed treatments. Eighteen female patients with acne were trained by a makeup artist and advised to apply acne-designed, basic, and decorative cosmetics for 2–4 weeks, while their acne was appropriately treated. For evaluation of the severity of acne, the number of inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions were counted, and QoL and mental/emotional state were evaluated using several validated questionnaires (Skindex-16, General Health Questionnaire 30, World Health Organization QoL-26, Profile of Mood States, and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) prior to and at least 2 weeks following makeup applications. The severity of acne decreased significantly, and measures that assessed frustration, embarrassment, and depression also showed significant improvement. The authors concluded that QoL in patients with acne was as impaired as in patients suffering from a chronic inflammatory skin disease, such as atopic dermatitis. This highlights the importance of treating acne and the need to use cosmetic makeup without potential for causing irritation.56 Another study demonstrated that proper instruction from dermatologists regarding makeup and skin care also improved QoL in patients with acne.55

The most studied dermatological condition with regard to the effect of camouflage therapy on QoL is vitiligo. In every study, significant improvements in DLQI scores have been noted.10,54 Patients with vitiligo have heightened feelings of embarrassment and self-consciousness (as documented by greater degrees of impairment, determined by a DLQI ≥ 10), and report even greater improvements in life quality scales following camouflage makeup as compared with scores obtained for other conditions that have been studied.

Unlike the previously described studies assessing camouflage makeup for vitiligo and acne, there have been no reported studies which have specifically evaluated improvement in QoL following camouflage therapy for rosacea, melasma, psoriasis, or hemangiomas. However, there are reports in the literature suggesting makeup as a viable management strategy for visible lesions causing life difficulties.59,60 Thus, there is an increasing need to evaluate the use of camouflage therapy in these conditions, especially in combination with traditional medical therapies, because these techniques can provide dermatologists with adjunctive methodologies to increase patient satisfaction and compliance.

Personal experience

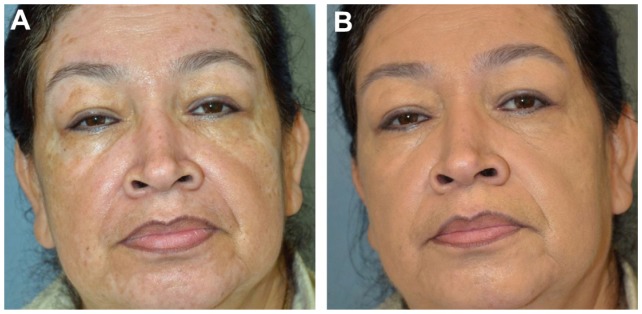

We have demonstrated patient satisfaction in utilizing cosmetic coverup (CoverFX Skin Care Inc, Ontario, Canada) products prior to beginning medical therapy in patients with visible facial skin lesions causing unwanted emotional stress (Figure 4A and B). Most patients request immediate results while awaiting the improvements from medical therapy. Cosmetic camouflage is extremely easy to use and learn (application process, ingredients, and choices for each skin types) and provides an additional therapeutic/cosmetic in our armamentarium of dermatological therapies. Most practitioners do not consider educating patients regarding these products, likely because they are not trained in their application, benefits, and ingredients. This underscores the importance of early education (in residency) regarding the cosmetic concerns of medical patients as well as the available over-the-counter products that many patients enquire about. Patients may switch physicians, especially if they feel that their physician does not address cosmetic concerns or have knowledge regarding the availability of products that may be of benefit in addition to the prescribed medical therapies. Almost every patient is willing to use makeup and follow a simple regimen at home with the right discussion. Patients with vitiligo, erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, or hemangiomas may require more coverage while those with melasma or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation may require increased time in skin matching to balance colors. Patients with acne may require coverups that will not irritate or worsen disease and can be integrated with prescribed medical therapies.

Figure 4.

Patient with (A) visible depigmented patches on the face (B) without evidence of any skin changes after application of cosmetic camouflage prior to initiation of ultraviolet B therapy.

Our patients were severe cases and described dramatic improvement after introduction of camouflage makeup. Although no systematic assessment of their QoL was performed, we conclude that additional research is needed to compare the available therapies with regard to ingredients, patient satisfaction, ease of use, and effects on concomitant medical treatments. Further, commitment of time and money may be a barrier to prolonged satisfaction. Future research should focus on the biological (eg, physical interaction between medical therapy and cosmetic coverup) and psychological effects (eg, whether patients are discouraged from treatments that are more time-consuming but bring lasting effects). Some modern products claim to have additional benefits, such as being sun-protective, anti-aging, and anti-inflammatory due to cosmeceutical (typically botanical) additives. Future studies may also seek to validate the claims of these products in a controlled fashion.

Conclusion

Camouflage therapy serves as a mechanism to help give immediate satisfaction to patients, although many physicians/residents do not consider this as a validated therapy. Many see camouflage therapy to be “submedical”, and thus it is rarely taught in residency training or beyond, and only offered in specialized clinics at large referral centers. It is important for dermatologists to provide this option to patients upon initial consultation because it provides immediate results and can be helpful while awaiting effects from medical treatment. In addition, studies show a rapid and dramatic improvement in QoL scores when used properly in addition to other therapies. Because improvement in QoL is related to patient satisfaction and compliance with medical treatment, makeup at the onset of treatment in specific cases may help increase patient satisfaction and yield improved clinical results. By increasing awareness and knowledge of cosmetic camouflage, physicians will be able to offer additional services and treatment options for patients suffering from skin lesions causing emotional distress, help to build confidence in the patient-physician relationship, improve patient QoL, and increase compliance with concurrent medical therapies.

Acknowledgment

Informed consent and permission to reproduce and publish these photos was obtained from all patients undergoing treatment in our practice.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Fried RG, Wechsler A. Psychological problems in the acne patient. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(4):237–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayer J, Burrows N. Acne: more than skin deep. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(970):500–506. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.045377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn LK, O’Neill JL, Feldman SR. Acne in adolescents: quality of life, self-esteem, mood, and psychological disorders. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. Depression and suicidal ideation in dermatology patients with acne, alopecia areata, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):846–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta MA, Schork NJ, Gupta AK, Kirkby S, Ellis CN. Suicidal ideation in psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(3):188–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ginsburg IH, Link BG. Psychosocial consequences of rejection and stigma feelings in psoriasis patients. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32(8):587–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb05031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ongenae K, Van Geel N, De Schepper S, Naeyaert JM. Effect of vitiligo on self-reported health-related quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152(6):1165–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radtke MA, Schäfer I, Gajur A, Langenbruch A, Augustin M. Willingness- to-pay and quality of life in patients with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(1):134–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aksoy B, Altaykan-Hapa A, Egemen D, Karagöz F, Atakan N. The impact of rosacea on quality of life: effects of demographic and clinical characteristics and various treatment modalities. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(4):719–725. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ongenae K, Dierckxsens L, Brochez L, van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Quality of life and stigmatization profile in a cohort of vitiligo patients and effect of the use of camouflage. Dermatology. 2005;210(4):279–285. doi: 10.1159/000084751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan SR, Tope WD. Pulsed dye laser treatment of rosacea improves erythema, symptomatology, and quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(4):592–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kini SP, Nicholson K, DeLong LK, et al. A pilot study in discrepancies in quality of life among three cutaneous types of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):1069–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotterill JA, Cunliffe WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(2):246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18131897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balkrishnan R, McMichael AJ, Camacho FT, et al. Development and validation of a health-related quality of life instrument for women with melasma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(3):572–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandya AG, Guevara IL. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18(1):91–8. ix. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawaskar MD, Parikh P, Markowski T, McMichael AJ, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Melasma and its impact on health-related quality of life in Hispanic women. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18(1):5–9. doi: 10.1080/09546630601028778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim IH, Feldman SR. The compliance pyramid. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22(4):185–186. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2011.603655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yentzer BA, Ade RA, Fountain JM, et al. Improvement in treatment adherence with a 3-day course of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2010;86(4):208–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunliffe WJ. Strategy of treating acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1992;1:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashcroft DM, Dimmock P, Garside R, Stein K, Williams HC. Efficacy and tolerability of topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330(7490):516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38376.439653.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghi A, Mantovani L, Minghetti S, Virgili A, Bettoli V. Acute acne flare following isotretinoin administration: potential protective role of low starting dose. Dermatology. 2009;218(2):178–180. doi: 10.1159/000182270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felsten LM, Alikhan A, Petronic-Rosic V. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview Part II: treatment options and approach to treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(3):493–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwinter J, Pelletier J, Khambalia A, Pope E. High-potency steroid use in children with vitiligo: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Falabella R, Barona MI. Update on skin repigmentation therapies in vitiligo. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22(1):42–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theobald K, Bradshaw M, Leyden J. Anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline (40 mg controlled-release) confers maximum anti-inflammatory efficacy in rosacea. Skinmed. 2007;6(5):221–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.06460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernstein EF, Kligman A. Rosacea treatment using the new-generation, high-energy, 595 nm, long pulse-duration pulsed-dye laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2008;40(4):233–239. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark SM, Lanigan SW, Marks R. Laser treatment of erythema and telangiectasia associated with rosacea. Lasers Med Sci. 2002;17(1):26–33. doi: 10.1007/s10103-002-8263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leonardi-Bee J, Batta K, O’Brien C, Bath-Hextall FJ. Interventions for infantile haemangiomas (strawberry birthmarks) of the skin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;5:CD006545. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006545.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saafan AM, Salah MM. Using pulsed dual-wavelength 595 and 1064 nm is more effective in the management of hemangiomas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(4):310–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wareham WJ, Cole RP, Royston SL, Wright PA. Adverse effects reported in pulsed dye laser treatment for port wine stains. Lasers Med Sci. 2009;24(2):241–246. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0560-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meijs MM, Blok FA, de Rie MA. Treatment of poikiloderma of Civatte with the pulsed dye laser: a series of patients with severe depigmentation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(10):1248–1251. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rayner VL. Cosmetic rehabilitation. Dermatol Nurs. 2000;12(4):267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rayner VL. Camouflage therapy. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13(2):467–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antoniou C, Stefanaki C. Cosmetic camouflage. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2006;5(4):297–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2006.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lotioncrafter [homepage on the Internet] Willow bark extract. [Accessed December 26, 2011]. Available from: http://www.lotioncrafter.com/willow-bark-extract.html.

- 36.Dermablend [homepage on the Internet] Find your shade. [Accessed December 26, 2011]. Available from: http://www.dermablend.com/findyourshade/

- 37.Boehncke WH, Ochsendorf F, Paeslack I, Kaufmann R, Zollner TM. Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12(6):577–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rayner VL. Assessing camouflage therapy for the disfigured patient: a personal perspective. Dermatol Nurs. 1990;2(2):101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basra MK, Fenech R, Gatt RM, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The Dermatology Life Quality Index 1994–2007: a comprehensive review of validation data and clinical results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159(5):997–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(5):707–713. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12365600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ. Improved discriminative and evaluative capability of a refined version of Skindex, a quality-of-life instrument for patients with skin diseases. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(11):1433–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Sahay AP, Sands LP. Measurement properties of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Cutan Med Surg. 2001;5(2):105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02737863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oztürkcan S, Ermertcan AT, Eser E, Sahin MT. Cross validation of the Turkish version of dermatology life quality index. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45(11):1300–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takahashi N, Suzukamo Y, Nakamura M, et al. Japanese version of the Dermatology Life Quality Index: validity and reliability in patients with acne. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al Ghamdi KM, Al Shammari SA. Arabic version of Skindex-16: translation and cultural adaptation, with assessment of reliability and validity. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(3):247–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Higaki Y, Kawamoto K, Kamo T, Horikawa N, Kawashima M, Chren MM. The Japanese version of Skindex-16: a brief quality-of-life measure for patients with skin diseases. J Dermatol. 2002;29(11):693–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones-Caballero M, Peñas PF, García-Díez A, Badía X, Chren MM. The Spanish version of Skindex-29. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39(12):907–912. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Finlay AY, Khan GK, Luscombe DK, Salek MS. Validation of Sickness Impact Profile and Psoriasis Disability Index in Psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123(6):751–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb04192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gupta MA, Gupta AK. The Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory: a preliminary index of psoriasis-related stress. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75(3):240–243. doi: 10.2340/0001555575240243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Augustin M, Gajur AI, Reich C, Rustenbach SJ, Schaefer I. Benefit evaluation in vitiligo treatment: development and validation of a patient-defined outcome questionnaire. Dermatology. 2008;217(2):101–106. doi: 10.1159/000128992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nicholson K, Abramova L, Chren MM, Yeung J, Chon SY, Chen SC. A pilot quality-of-life instrument for acne rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holme SA, Beattie PE, Fleming CJ. Cosmetic camouflage advice improves quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147(5):946–949. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanioka M, Yamamoto Y, Kato M, Miyachi Y. Camouflage for patients with vitiligo vulgaris improved their quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9(1):72–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1473-2165.2010.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matsuoka Y, Yoneda K, Sadahira C, Katsuura J, Moriue T, Kubota Y. Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33(11):745–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashi N, Imori M, Yanagisawa M, Seto Y, Nagata O, Kawashima M. Make-up improves the quality of life of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15(4):284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tedeschi A, Dall’Oglio F, Micali G, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Corrective camouflage in pediatric dermatology. Cutis. 2007;79(2):110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tanioka M, Miyachi Y. Waterproof camouflage age for vitiligo of the face using Cavilon 3M as a spray. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18(1):93–94. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gupta AK, Chaudhry MM. Rosacea and its management: an overview. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19(3):273–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Prignano F, Ortonne JP, Buggiani G, Lotti T. Therapeutical approaches in melasma. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25(3):337–342. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]