Abstract

Sandfly-transmitted phleboviruses, such as Toscana, sandfly fever Sicilian, and sandfly fever Naples, can cause human disease and circulate at high rates in Mediterranean countries. Previous studies have also established that viruses other than phleboviruses may be detected in and isolated from sand flies. The recent detection and isolation (in a large variety of mosquito species) of insect-only flaviviruses related to cell fusing agent virus has indicated that the latter is not an evolutionary remnant but the first discovered member of a group of viruses, larger than initially assumed, that has high genetic heterogeneity. Insect-only flaviviruses have been detected in and/or isolated from various species of mosquitoes, but nevertheless only from mosquitoes to date; other dipterans have not been screened for the presence of insect-only flaviviruses. The possible presence of flaviviruses, including insect-only flaviviruses, was investigated in sand flies collected around the Mediterranean during a trapping campaign already underway. Accordingly, a total of 1508 sand flies trapped in France and Algeria, between August 2006 and July 2007, were tested for the presence of flaviviruses using a PCR assay previously demonstrated experimentally to amplify all recognized members of the genus Flavivirus, including insect-only flaviviruses. Two of 67 pools consisting of male Phlebotomus perniciosus trapped in Algeria were positive. The two resulting sequences formed a monophyletic group and appeared more closely related to insect-only flaviviruses associated with Culex mosquitoes than with Aedes mosquitoes, and more closely related to insect-only flaviviruses than to arthropod-borne or to no-known-vector vertebrate flaviviruses. This is the first description of insect-only flaviviruses in dipterans distinct from those belonging to the family Culicidae (including Aedes, Culex, Mansonia, Culiseta, and Anopheles mosquito genera), namely sand flies within the family Psychodidae. Accordingly, we propose their designation as phlebotomine-associated flaviviruses.

Keywords: Aedes, Arbovirus(es), Culex, Mosquito(es), Sandfly (Sandflies)

Introduction

Recent interest in sand fly–associated viruses has demonstrated that Toscana, sandfly fever Sicilian, and sandfly fever Naples viruses, all causing disease in humans, circulate at unexpectedly high rates in Mediterranean countries (Charrel et al. 2005, Izri et al. 2008, Charrel, personal observations). As the organization of sand fly trapping campaigns is demanding in terms of logistics and morphological identification, entomological collections should be tested for the largest possible panel of microorganisms. Previous studies have established that viruses other than phleboviruses may be detected in and isolated from sand flies (Fontenille et al. 1994). The recent detection and isolation (in a large variety of mosquito species) of insect-only flaviviruses related to cell fusing agent virus (CFAV) has indicated that the latter is not an evolutionary remnant, but the first known member of a group of viruses, much larger than initially assumed, that has high genetic heterogeneity. CFAV, originally isolated from an Aedes aegypti cell line (Stollar and Thomas 1975), was detected in and isolated from a natural mosquito population consisting of Ae. aegypti, Ae. Albopictus, and Culex sp. in Puerto Rico (Cook et al. 2006). CFAV was also detected in Ae. aegypti in Thailand (Kihara et al. 2007) and in Ae. aegypti and Mansonia titillans in Argentina (unpublished data; Genbank accession no. DQ335466, DQ335467, DQ431718). Kamiti River virus (KRV) was isolated in Kenya in 1999 from Ae. Macintoshi (Sang et al. 2003). A distant variant was isolated from Cx. pipiens, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, and Cx. quinquefasciatus in Japan (Hoshino et al. 2007) and from Cx. quinquefasciatus in Guatemala (Morales-Betoulle et al. 2008). Sequences corresponding to possible new insect-only flaviviruses have also been detected in Ochlerotatus caspius, Ae. vexans, Cx. theileri, Anopheles atroparvus, and Culiseta annulata in Spain (Aranda et al. 2008). Unfortunately, sequences documented in the latter article are not available in Genbank, and thus could not be included in our phylogenetic analyses. To summarize, insect-only flaviviruses have been detected in and/or isolated from various species of mosquitoes only to date, and other arthropods have not been screened for these viruses. We decided to investigate the possible presence of novel insect-only flaviviruses and other known flaviviruses in sand flies collected around the Mediterranean during a trapping campaign already underway.

Materials and Methods

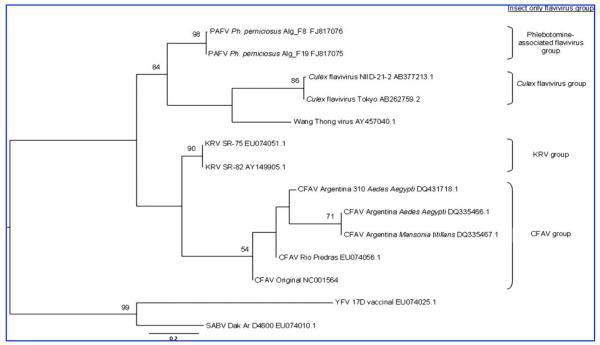

Accordingly, a total of 1508 sand flies trapped in France and Algeria between August 2006 and July 2007 were screened for flaviviruses using a PCR test previously experimentally demonstrated to amplify all recognized members of the genus Flavivirus, including insect-only flaviviruses (Moureau et al. 2007). A total of 67 pools were tested by seminested PCR using an additional PF3S primer (5′-ATH TGG TWY ATG TGG YTD GG, position 8941–8960 in the open reading frame of yellow fever virus [Genbank NC_002031]). The expected product size was 197 bp, resulting in a 157 nt sequence (primers excluded). Two pools consisting of male Phlebotomus perniciosus (2 pools of 30 individuals, each) trapped in Algeria were positive. Two PCR products of the expected size were gel purified, cloned into pCRII (TA Cloning Kit Dual Promoter; Invitrogen, Cergy Pontoise, France), and sequenced in both directions using M13 primers (Genbank accession no. FJ817075 and FJ817076). To ensure that positive pools represented viral RNA, samples were tested under the same conditions and protocols but excluding a reverse transcription step. Sequencher (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to combine reverse and forward sequences, and final datasets were compiled using Se-Al (available from tree.bio.ed.ac.uk). Sequences were combined with those currently available in GenBank using the BLASTN algorithm (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/) and were revealed to be more closely related to insect-only flaviviruses such as CFAV and KRV. Saboya virus sequence was also included in the analysis since it was isolated from sand flies (Fontenille et al. 1994). Sequences were aligned using either MUSCLE for maximum likelihood (ML) analyses (Edgar 2004) or Clustal × 1.83. Selection of the model of nucleotide substitution and initial parameter values was conducted via MODELTEST (Posada and Crandall 1998). ML phylogenetic trees were then estimated in GARLI (Zwickl 2006) and PAUP (Swofford 2000) using the GTR + G (gamma) + I model of nucleotide substitution. The substitution matrix, base composition, gamma distribution of among-site rate variation (G), and the proportion of invariant sites (I) are available from the authors on request. To assess the robustness of particular phylogenetic groupings, a bootstrap resampling analysis was undertaken using 1000 replicate neighbor-joining trees using the ML substitution matrix described above, in PAUP (Fig. 1). Phylogenetic analyses were also performed in MEGA 4.0 via neighbor joining using the Jukes-Cantor algorithm and via maximum parsimony.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic reconstruction of insect-only flaviviruses, rooted using yellow fever and Saboya viruses. ML tree and bootstrap proportions of greater than 50% are shown.

Results and Discussion

The three resulting phylograms provided similar tree topologies using the three different techniques (data not shown) and indicated that the two novel sequences determined from Ph. perniciosus were more closely related to insect-only flaviviruses than to arthropod-borne and no-known-vector vertebrate flaviviruses. Genetic and phylogenetic analyses indicate that both sequences are clearly distinct from other insect-only flaviviruses previously described, and constitute a unique and new lineage. CFAV and KRV formed a distinct lineage that can be subdivided into CFAV- and KRV-related sequences. Sequences derived from Culex mosquitoes grouped together. Finally, the two phlebotomine-derived sequences grouped together in an ndependent lineage that appeared more closely related to Culex-derived than to Aedes-derived sequences, and are proposed to be designated as phlebotomine-associated flavivirus (PAFV). Unfortunately, virus isolation could not be attempted due to the fact that sand flies were preserved in guanidinium thiocyanate. These results should be considered as preliminary; longer sequences and additional sequence data are necessary to increase our understanding of insect-only flaviviruses circulating in sand flies. However, the three different phylogenetic methods used in this study provided comparable results, and flaviviruspositive results were not obtained when a reverse transcription step was absent, both of which strongly support the fact that insect-only flaviviruses can be found in phlebotomine flies. The significance of this finding within the natural cycle of the viruses in the field remains unknown. To address the role of sand flies in flavivirus transmission, further seroprevalence studies that investigate the presence of specific antibodies in vertebrates living in areas where sand flies predominate over mosquitoes are necessary. This justifies further investigation of arthropod-borne flaviviruses in sand flies as previously described with Saboya virus, and field campaigns will shortly be organized with the aim of isolating these sand fly flaviviruses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by (i) the European Commission through the 6th Framework Program for Research and Technological Development project under the VIZIER project (LSHG-CT-2004-511960), (ii) the Rivigene project, and (iii) internal funding from the Aix-Marseille University and the Institute of Research for Development.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement Authors have no conflict of interest in relation with this study.

References

- Aranda C, Sanchez-Seco MP, Caceres F, Escosa R, et al. Detection and monitoring of mosquito flaviviruses in Spain between 2001 and 2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:171–178. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrel RN, Gallian P, Navarro-Mari JM, Nicoletti L, et al. Emergence of Toscana virus in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1657–1663. doi: 10.3201/eid1111.050869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook S, Bennett SN, Holmes EC, De Chesse R, et al. Isolation of a new strain of the flavivirus cell fusing agent virus in a natural mosquito population from Puerto Rico. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:735–748. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenille D, Traore-Lamizana M, Trouillet J, Leclerc A, et al. First isolations of arboviruses from phlebotomine sand flies in West Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:570–574. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.50.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino K, Isawa H, Tsuda Y, Yano K, et al. Genetic characterization of a new insect flavivirus isolated from Culex pipiens mosquito in Japan. Virology. 2007;359:405–414. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izri A, Temmam S, Moureau G, Hamrioui B, et al. Sandfly fever Sicilian virus, Algeria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:795–797. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.071487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kihara Y, Satho T, Eshita Y, Sakai K, et al. Rapid determination of viral RNA sequences in mosquitoes collected in the field. J Virol Methods. 2007;146:372–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Betoulle ME, Monzon Pineda ML, Sosa SM, Panella N, et al. Culex flavivirus isolates from mosquitoes in Guatemala. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:1187–1190. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[1187:cfifmi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moureau G, Temmam S, Gonzalez JP, Charrel RN, et al. A real-time RT-PCR method for the universal detection and identification of flaviviruses. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:467–477. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2007.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang RC, Gichogo A, Gachoya J, Dunster MD, et al. Isolation of a new flavivirus related to cell fusing agent virus (CFAV) from field-collected flood-water Aedes mosquitoes sampled from a dambo in central Kenya. Arch Virol. 2003;148:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s00705-003-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stollar V, Thomas VL. An agent in the Aedes aegypti cell line (Peleg) which causes fusion of Aedes albopictus cells. Virology. 1975;64:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (* and Other Methods) Version 4 Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zwickl DJ. Genetic algorithm approaches for the phylogenetic analysis of large biological sequence datasets under the maximum likelihood criterion. University of Texas; Austin: 2006. Ph.D. dissertation. [Google Scholar]