Abstract

Objective

Spondyloarthritis is an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease with important clinical impact, although the frequency is uncertain. We sought to assess the cumulative incidence and clinical spectrum of spondyloarthritis in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) in a population-based cohort.

Methods

The medical records of a population-based cohort of Olmsted County, Minnesota residents diagnosed with CD between 1970 and 2004 were reviewed. Patients were followed longitudinally until migration, death, or December 31, 2010. We used the European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria and modified New York criteria to identify patients with spondyloarthritis. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis following CD diagnosis.

Results

The cohort included 311 patients with CD (49.8% females; median age, 29.9 years [range, 8–89]). Thirty-two patients developed spondyloarthritis based on ASAS criteria. The cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis after CD diagnosis was 6.7% (95% confidence interval, 2.5%–6.7%) at 10 years, 13.9% (8.7%–18.8%) at 20 years, and 18.6% (11.0%–25.5%) at 30 years. The 10-year cumulative incidence of ankylosing spondylitis was 0 while both the 20-year and 30-year cumulative incidences were 0.5% (95% CI, 0–1.6%).

Conclusions

We have for the first time defined the actual cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in CD using complete medical record information in a population-based cohort. The cumulative incidence of all forms of spondyloarthritis increased to approximately 19% by 30 years from CD diagnosis. Our results emphasize the importance of maintaining a high level of suspicion for spondyloarthritis when following patients with CD.

Keywords: Spondyloarthritis, Crohn’s disease, epidemiology, ankylosing spondylitis

INTRODUCTION

Arthritis is one of the most common extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with a 10–35% prevalence reported in patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (1). IBD has been associated with both axial and peripheral arthritis. The prevalence of axial arthritis has been estimated in the literature to be 3–25%, while peripheral arthritis occurs in about 5–20% of patients (1–3).

The peripheral arthritis associated with IBD is usually seronegative (i.e., rheumatoid factor is absent) and nonerosive; however, erosive disease that affects the hip, elbows, metacarpophalangeal, and metatarsophalangeal joints has been described in IBD (3). Pauciarticular peripheral arthritis is strongly correlated with other extraintestinal manifestations of IBD such as erythema nodosum and uveitis, and often occurs in association with active bowel symptoms. Polyarticular peripheral arthritis is associated with uveitis but no other extraintestinal manifestations and is not as strongly associated with IBD activity (3–5).

Axial involvement includes sacroiliitis and spondylitis. The ankylosing spondylitis of Crohn’s disease is mainly asymmetric, in contrast to idiopathic ankylosing spondylitis (6–9).

The frequency with which spondyloarthritis occurs in patients with Crohn’s disease is not well studied. A population-based report from Norway concluded that the prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis is 3.7% in patients seen six years after diagnosis of IBD (10). This study also described the occurrence of psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis in IBD to be 0.8%, 0.5%, and 17%, respectively (10). Ankylosing spondylitis occurred significantly more often in patients with IBD than in the general population, and was more common in men. HLA-B27, peripheral arthritis, enthesitis and uveitis were significantly more common in patients with IBD who have associated ankylosing spondylitis compared to patients with IBD who did not have ankylosing spondylitis (10).

To date, no population-based cohort study that describes the incidence of spondyloarthritis in patients with IBD has been published. We sought to examine both the cumulative incidence and clinical features of spondyloarthritis in a population-based U.S. cohort of patients with Crohn’s disease.

METHODS

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a unique medical records linkage system developed in the 1950s and supported by the National Institutes of Health. It exploits the fact that virtually all of the health care for the residents of Olmsted County is provided by two organizations: Mayo Medical Center, consisting of Mayo Clinic and its two affiliated hospitals (Rochester Methodist and Saint Marys), and Olmsted Medical Center, consisting of a smaller multispecialty clinic and its affiliated hospital (Olmsted Community Hospital). In any three-year period, over 90% of county residents are examined at either one of the two health care systems (11). Diagnoses generated from all outpatients visits, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, nursing home visits, surgical procedures, autopsy examinations, and death certificates are recorded in a central diagnostic index. Thus, it is possible to identify all diagnosed cases of a given disease for which patients sought medical attention.

The resources of the REP were used to identify a population-based cohort of patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease from 1970 through 2004 (12–14). All cases of Crohn’s disease were diagnosed based on a consistently used definition – cases had to meet at least two of the following criteria: 1) clinical history of abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, malaise, and/or rectal bleeding; 2) endoscopic findings of mucosal cobblestoning, linear ulceration, skip areas, or perianal disease; 3) radiological findings of strictures, fistula, mucosal cobblestoning, or ulceration; 4) macroscopic appearance of bowel wall induration, mesenteric lymphadenopathy, and “creeping fat” at laparotomy; or 5) pathological findings of transmural inflammation and/or epithelioid granulomas (12).

Lifetime data on musculoskeletal symptoms and disease were retrospectively recorded, and the patients were followed longitudinally until moving from Olmsted County, death, or December 31, 2010. Approval for the study was obtained from the institutional review boards of Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center.

The European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) criteria, modified New York criteria, and Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria were retrospectively applied in identifying patients with spondyloarthritis (7–9, 15). Demographic data including gender, date of birth, and date of Crohn’s disease diagnosis were recorded as previously described (12–14), as well as anatomic location of Crohn’s disease, date of arthropathy diagnosis by the treating physician, diagnosis of another primary inflammatory arthritis, family history of arthropathy, and characteristics of spondyloarthritis. These included presence of inflammatory back pain, synovitis, psoriasis, nongonococcal urethritis/cervicitis, alternating buttock pain, enthesitis, sacroiliitis (based on radiographs or magnetic resonance imaging), which was diagnosed both clinically and radiographically, uveitis, limitation in spine motion, lumbar spine pain, limitation of chest expansion, radiographic evidence of ankylosis, HLA B-27 status, oligoarthritis and specific joints involved, or polyarthritis and specific joints involved; this information was recorded based on physician diagnosis in the medical record. The abstracted data included diagnoses of spondyloarthritis or its clinical features seen in usual practice by treating physicians, most often a primary care physician or rheumatologist. Diagnoses of uveitis and psoriasis were made by an ophthalmologist or dermatologist, respectively.

Diagnosis of specific forms of spondyloarthritis included those based on treating physician diagnosis. All patients who had either inflammatory back pain or synovitis were included in our study as having spondyloarthritis based on the ESSG criteria since all of these patients already carried a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (7–9), (15). Patients were also included as having ankylosing spondylitis if there was evidence of either limitation in spine motion and lumbar spine pain in the setting of radiographic evidence of ankylosis based on the modified New York criteria for this disease (15). Finally, all patients who had arthritis, enthesitis, or dactylitis were included in our study as having spondyloarthritis based on the ASAS criteria since all of these patients already carried a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (8,9).

In addition to including treating physician diagnoses of spondyloarthritis, we searched individual medical records for features of this disease even when a formal diagnosis was not made; those with features of spondyloarthritis that correlated with the ESSG and ASAS criteria were included as having this diagnosis. All records were abstracted by RS with independent abstraction and confirmation of the features of spondyloarthritis by ELM.

The cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis after Crohn’s disease diagnosis was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for the observed proportions (%) were based on the exact binomial distribution. The prevalence of psoriasis, nongonococcal urethritis/cervicitis, alternating buttock pain, enthesitis, sacroiliitis, uveitis, plantar fasciitis, Achilles tendonitis, oligoarthritis, and polyarthritis were also calculated.

RESULTS

Incidence

A total of 311 patients with Crohn’s disease were identified, of whom 49.8% were women, and the median age at diagnosis of Crohn’s was 29.9 years (range, 8–89 years) (Table 1). Prior to Crohn’s disease diagnosis, based on the ESSG criteria, the prevalence of spondyloarthritis was 1.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.4%–3.3%), with 4 patients from the total of 311 patients with Crohn’s disease who had been diagnosed with spondyloarthritis prior to the diagnosis of Crohn’s. No patients carried a diagnosis of ankylosing spondylitis. Based on the ASAS criteria, 13 patients from the total of 311 patients with Crohn’s disease had been diagnosed with spondyloarthritis prior to a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease; therefore, the prevalence of spondyloarthritis based on ASAS criteria prior to Crohn’s diagnosis was 4.2% (2.2%–7.0%). The median number of years from time of spondyloarthritis diagnosis to Crohn’s disease diagnosis in these patients was 5.5 years (range: 0.2–43.5 years). The patients diagnosed with spondyloarthritis prior to Crohn’s diagnosis were excluded from analysis of arthritis incidence subsequent to Crohn’s diagnosis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 311 patients in the Olmsted County, Minnesota population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease (1970–2004).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 156 (50.2) |

| Female | 155 (49.8) |

| Age at Diagnosis | |

| Less than 18 years | 43 (13.8) |

| 18–40 years | 163 (52.4) |

| More than 40 years | 105 (33.8) |

| Disease location | |

| Small bowel | 101 (32.5) |

| Ileocolitis | 104 (33.7) |

| Colitis | 106 (34.1) |

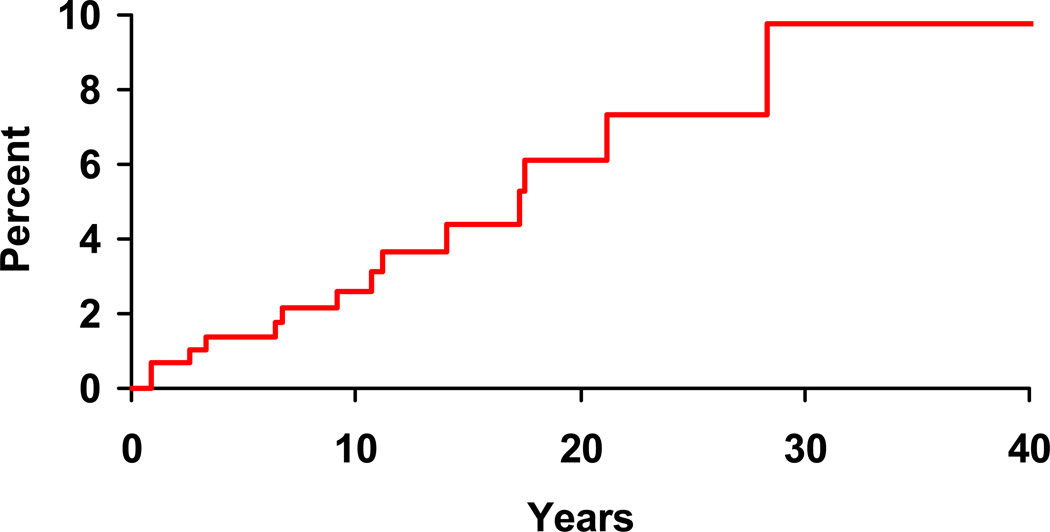

Following the incident date of Crohn’s disease diagnosis, 14 of 307 patients were diagnosed with spondyloarthritis according to the ESSG criteria. The cumulative incidence of a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis after an established diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was 2.6% (95% CI, 0.7%–4.5%) at 10 years, 6.1% (2.4%–9.7%) at 20 years, and 9.8% (3.2%–15.8%) at 30 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence (1 minus survival free) of any spondyloarthritis (based on European Spondyloarthropathy Study Group criteria) from Crohn’s disease diagnosis among 307 Olmsted County, Minnesota residents with Crohn’s disease (1970–2004).

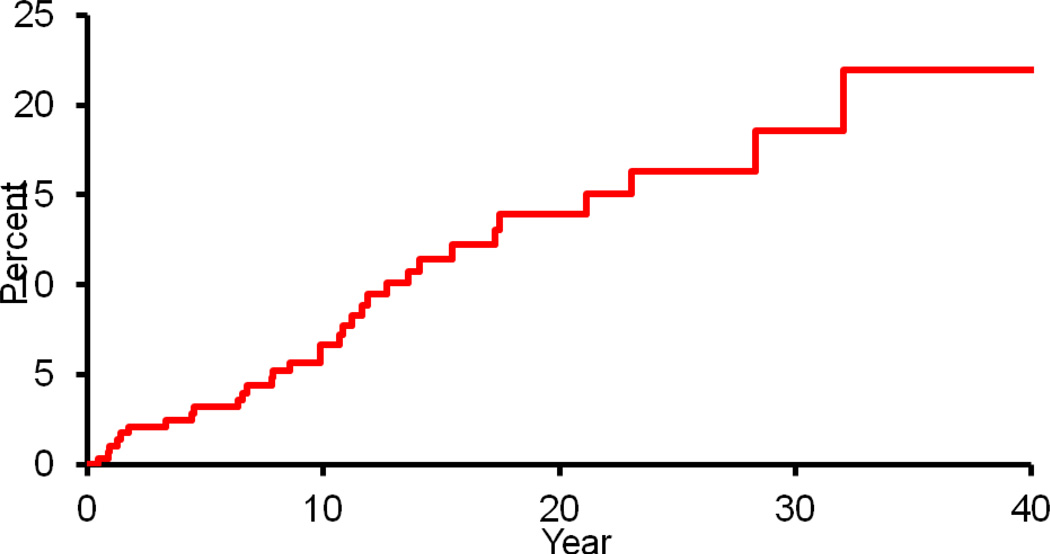

According to the ASAS criteria, 32 of 298 patients were diagnosed with spondyloarthritis following a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. The cumulative incidence of a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis after an established diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was 6.7% (95% CI, 3.5%–9.7%) at 10 years, 13.9% (8.7%–18.8%) at 20 years, and 18.6% (11%–25.5%) at 30 years (Figure 2). The median number of years from time of Crohn’s disease diagnosis to spondyloarthritis diagnosis in these patients was 9.9 years (range: 0.4–32.0 years).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence (1 minus survival free) of any spondyloarthritis (based on Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society classification criteria) from Crohn’s disease diagnosis among 298 Olmsted County, Minnesota residents with Crohn’s disease (1970–2004).

In our cohort, a total of 18 patients were diagnosed with spondyloarthritis and 2 were specifically diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis based on the ESSG criteria in the pre- and post-Crohn’s disease diagnosis periods. Fourteen out of 18 patients who carried a diagnosis of spondyloarthritis were female; in the ankylosing spondylitis group, 1 of 2 patients was female. The majority of patients diagnosed with either spondyloarthritis or ankylosing spondylitis had associated Crohn’s ileocolitis or colitis rather than ileitis. In those diagnosed with spondyloarthritis, Crohn’s ileitis, ileocolitis, and colitis was present in 11% (2 out of 18), 50% (9 out of 18), and 39% (7 out of 18) of patients, respectively. Finally, in patients diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, none had Crohn’s ileitis while one patient had ileocolitis and one had colitis.

A total of 45 patients were diagnosed with spondyloarthritis based on ASAS criteria in the pre- and post-Crohn’s disease diagnosis periods. 30 out of these 45 patients were female. The majority of these patients had Crohn’s ileocolitis or colitis rather than ileitis. Specifically, Crohn’s ileitis, ileocolitis, and colitis were present in 18% (8 out of 45), 33% (15 out of 45), and 49% (22 out of 45), respectively.

Subtypes

Ankylosing spondylitis was diagnosed in 2 of 311 patients after Crohn’s disease diagnosis. The 10-year cumulative incidence of ankylosing spondylitis was 0, while both the 20-year and 30-year cumulative incidences were 0.5% (95% CI, 0–1.6%). There were no physician diagnoses of reactive, psoriatic, or undifferentiated spondyloarthritis found in our cohort.

Clinical Characteristics

Clinical features of the spondyloarthritis in the total cohort of 311 patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of spondyloarthritis in the 311 patients with Crohn’s disease from a population-based cohort of Olmsted County, Minnesota residents.

| Spondyloarthritis Feature |

Features Present Prior to Crohn’s Diagnosis (number of patients) |

Features Appearing After Crohn’s Diagnosis (number of patients) |

|---|---|---|

| Psoriasis | 5 | 9 |

| Urethritis/Cervicitis | 1 | 0 |

| Buttock pain | 1 | 6 |

| Plantar fasciitis | 4 | 12 |

| Achilles tendonitis | 4 | 4 |

| Sacroiliitis | 0 | 5 |

| Uveitis | 2 | 10 |

| Oligoarthritis | 3 | 9 |

| Polyarthritis | 3 | 7 |

| Inflammatory back pain* | 0 | 2 |

see Discussion

DISCUSSION

The major aim of this study was to define the incidence and clinical features of spondyloarthritis in patients with Crohn’s disease. To our knowledge, this study is the first to define the actual cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis in a population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease using complete medical record information. Specifically, the cumulative incidence of any spondyloarthritis increased to about one in 10 patients by 30 years from Crohn’s disease diagnosis based ESSG criteria and about one in 5 patients by 30 years after Crohn’s diagnosis according to ASAS criteria.

The occurrence of clinical features of spondyloarthritis became more frequent following the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. Notably, there were no diagnoses of sacroiliitis prior to Crohn’s disease diagnosis; however, the incidence of this diagnosis increased to 1.6% following the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. Also, the incidences of buttock pain, plantar fasciitis, uveitis, oligoarthritis, and polyarthritis more than doubled following the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. The most common feature prior to a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was psoriasis, while the most common feature following the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was plantar fasciitis. The HLA-B27 status among patients with spondyloarthritis would be interesting but this was not systematically assessed in our patients since it is not a routinely obtained laboratory study.

Our results are in contrast to those from Bernstein and colleagues, who reported that uveitis/iritis was the most common extraintestinal manifestation in Crohn’s disease (2). However, theirs was a prevalence study that abstracted the following five diagnoses using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes: primary sclerosing cholangitis, ankylosing spondylitis, uveitis/iritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and erythema nodosum. In contrast, we studied the cumulative incidence of these conditions, and diagnoses were based on data abstracted from the actual medical record.

A cross-sectional population-based study from Norway of the prevalence of spondyloarthritis and associated clinical characteristics in 406 patients with Crohn’s disease and six-year physician follow-up revealed the prevalence of AS to be 6.0%, and that of spondyloarthropathy to be 26% (10). The occurrence of enthesitis, uveitis, and peripheral arthritis was more common in those who met criteria to be diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis rather than those diagnosed with just inflammatory back pain or sacroiliitis.

Several other studies have described the prevalence of articular manifestations and spondyloarthritis in Crohn’s disease (16–19). In particular, the study by Salvarani, et al. is a cross-sectional study from Italy and the Netherlands, whereas ours is a true population-based cohort. In contrast to these previous studies, our study was an incidence study with up to 30-year follow-up from Crohn’s disease diagnosis. Although the number of patients in our study is smaller, the study has the advantages of identifying features of spondyloarthritis based on chart-based data abstraction of physician diagnoses and a large number of person-years of follow-up along with information about the presence of spondyloarthritis features prior to the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease.

Patients in our study diagnosed with spondyloarthritis were more likely to have either Crohn’s ileocolitis or colitis compared to Crohn’s ileitis based on both ESSG and ASAS criteria. This finding is in agreement with Greenstein et al, who reported that extraintestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease were more likely to be associated with colonic disease (42%) when compared to small bowel disease (20). Increased gut permeability has been discussed in the setting of IBD and perhaps this phenomenon is more often seen in the colon (6). Higher permeability of the colon at sites affected by Crohn’s disease could lead to translocation of activated T cells to joints and thereby cause inflammation. The pathobiology of the association of IBD and spondyloarthritis remains to be fully elucidated.

The cumulative incidence of spondyloarthritis was higher using the ASAS criteria. Unlike the ESSG criteria, the ASAS criteria employ (but do not obligate) the use of magnetic resonance imaging in addition to radiographic data to diagnose sacroiliitis; and magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive for sacroiliac inflammation. Also, a diagnosis of peripheral spondyloarthritis based on ASAS criteria requires a diagnosis of arthritis, dactylitis, or enthesitis, plus a feature of spondyloarthritis, which includes Crohn’s disease (21). Since more patients in our cohort were diagnosed with arthritis or enthesitis rather than inflammatory back pain or pure synovitis (as required by ESSG criteria), the incidence of any spondyloarthritis was higher when the ASAS criteria were applied.

This study included only patients who came to clinical attention for extraintestinal spondyloarthritis-related symptoms. Systematic screening of all patients with Crohn’s disease, for example by radiographic imaging of the sacroiliac joints, was not performed. A further limitation is that not all patients were screened for features of spondyloarthropathy by a rheumatologist, which may have limited ascertainment of possible spondyloarthritis disease features. Additionally, a diagnostic approach to patients with Crohn’s disease to assess for spondyloarthritis and its features with use of classification criteria was likely not undertaken since most patients were seen by a primary care physician; likely there were fewer diagnoses seen in our cohort because of difficulty making this diagnosis without rheumatologist evaluation. The ESSG classification criteria call for a diagnosis of inflammatory back pain, which is a difficult diagnosis to make. As evidenced in our study as well as other studies, information about inflammatory back pain is very often either not systematically interrogated or captured in a way that permits recovery in retrospective medical record review, and likely was under diagnosed (7–9). However, this was a population-based study of patients seen in usual clinical practice, in which not all patients undergo subspecialty evaluation. Hence, our estimates based on ASAS and ESSG criteria might be regarded as the minimum estimate of incidence and disease feature frequency. Finally, a limitation in using the ESSG criteria in classifying spondyloarthritis is its low sensitivity and specificity in mild and early cases.

Ankylosing spondylitis is perhaps the most well-defined of the spondyloarthritides, and likely the diagnosis best recognized in the community. There were no diagnoses of reactive, undifferentiated, or psoriatic spondyloarthritides found in the medical records. We could not reliably evaluate the diagnostic criteria for these subtypes of spondyloarthritis in our analysis.

In summary, this study shows that the features of spondyloarthritis were most commonly diagnosed within the first ten years of Crohn’s disease diagnosis and the frequency of diagnosed spondyloarthritis increased from time of Crohn’s disease diagnosis. Additional studies are necessary to better define the immunobiology of spondyloarthritis in patients with IBD.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education & Research; and made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project [grant number R01 AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging].

This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in The Journal of Rheumatology following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version is available online at: http://jrheum.org/content/early/2012/09/12/jrheum.120321.full.pdf+html.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ardizzone S, Puttini PS, Cassinotti A, Porro GB. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008 Jul;40(Suppl 2):S253–S259. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(08)60534-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001 Apr;96(4):1116–1122. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourikas LA, Papadakis KA. Musculoskeletal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009 Dec;15(12):1915–1924. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juillerat P, Mottet C, Pittet V, Froehlich F, Felley C, Gonvers JJ, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn's disease. Digestion. 2007;76(2):141–148. doi: 10.1159/000111029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larsen S, Bendtzen K, Nielsen OH. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Ann Med. 2010 Mar;42(2):97–114. doi: 10.3109/07853890903559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meier C, Plevy S. Therapy insight: how the gut talks to the joints--inflammatory bowel disease and the spondyloarthropathies. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007 Nov;3(11):667–674. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dougados M, van der Linden S, Juhlin R, Huitfeldt B, Amor B, Calin A, et al. The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group preliminary criteria for the classification of spondylarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 Oct;34(10):1218–1227. doi: 10.1002/art.1780341003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudwaleit M, Landewe R, van der Heijde D, Listing J, Brandt J, Braun J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):770–776. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R, Listing J, Akkoc N, Brandt J, et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009 Jun;68(6):777–783. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.108233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palm O, Moum B, Ongre A, Gran JT. Prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis and other spondyloarthropathies among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population study (the IBSEN study) J Rheumatol. 2002 Mar;29(3):511–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011 May 1;173(9):1059–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loftus EV, Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998 Jun;114(6):1161–1168. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Tremaine WJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007 Mar;13(3):254–261. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingle SB, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Sandborn WJ. Increasing incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2001–2004 (abstract) Gastroenterology. 2007;132(4) Suppl 2:A19–A20. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum. 1984 Apr;27(4):361–368. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Vlam K, Mielants H, Cuvelier C, De Keyser F, Veys EM, De Vos M. Spondyloarthropathy is underestimated in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and HLA association. J Rheumatol. 2000 Dec;27(12):2860–2865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez VE, Costas PJ, Vazquez M, Alvarez G, Perez-Kraft G, Climent C, et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathy in Puerto Rican patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Ethn Dis. 2008 Spring;18(2) Suppl 2 S2-225-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salvarani C, Vlachonikolis IG, van der Heijde DM, Fornaciari G, Macchioni P, Beltrami M, et al. Musculoskeletal manifestations in a population-based cohort of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001 Dec;36(12):1307–1313. doi: 10.1080/003655201317097173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lanna CC, Ferrari Mde L, Rocha SL, Nascimento E, de Carvalho MA, da Cunha AS. A cross-sectional study of 130 Brazilian patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: analysis of articular and ophthalmologic manifestations. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Apr;27(4):503–509. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB. The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976 Sep;55(5):401–412. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rudwaleit M. New approaches to diagnosis and classification of axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:375–380. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32833ac5cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]